To assess the changes in food consumption pattern and glycosylated hemoglobin levels in patients with type 2 diabetes after an educational intervention.

Materials and methodsA descriptive study in people over 18 years of age with type 2 diabetes receiving the educational intervention provided by the health facilities of the Costa Rican Social Security. Sociodemographic, biochemical, and anthropometric variables were collected. Glycemic control was classified as good (≤7%), fair (7.1–8%), and poor (>8%). The usual daily diet record was used to assess the food consumption pattern based on the 11 criteria, divided into the following categories: poor compliance (0–3 criteria), fair compliance (4–7 criteria), and good compliance (8–11 criteria). Data collected were processed using SPSS version 16 software. A Student's t test was used for dependent samples. The impact of the educational intervention on metabolic control and food consumption pattern was determined using a McNemar test with a level of significance of 5% for hypothesis testing.

ResultsThe study sample consisted of 702 patients with a mean age of 54.5±11.6 years, 73.8% females. Mean initial glycosylated hemoglobin level was 8.8±2.14%, while final level was 7.8±1.78% (p<0.05). Glycosylated hemoglobin levels less than 7% were found in 23.9% of the population at study start and in 41.3% at study end. As regard the food consumption pattern, the mean number of criteria met was 6±3 at study start and 9±2 at study end (p<0.000). Mean glycosylated hemoglobin level showed at the start of intervention a similar behavior in all 3 categories of the food consumption pattern, and at the end the changes in glycosylated hemoglobin in the poor and fair compliance categories were statistically significant (p<0.022 and p<0.000 respectively), unlike in the good compliance category (p<0.065). At the end of the intervention, of the 75.6% of the population with good compliance, 41.3% had good metabolic control (p<0.0001). The educational intervention was significant (p<0.000) using the McNemar test.

ConclusionThe educational intervention approach to nutritional therapy had a positive impact on the food consumption pattern and glycosylated hemoglobin levels, showing that therapeutic education is part of the treatment of diabetes to achieve the objectives.

Determinar el comportamiento del patrón de consumo de alimentos y de la hemoglobina glicosilada en personas con diabetes tipo 2, después de una intervención educativa.

Materiales y métodosEstudio descriptivo en personas mayores de 18 años, con diabetes tipo 2, participantes en la intervención educativa brindada en los establecimientos de salud de la Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social. Se recogieron variables sociodemográficas, bioquímicas y antropométricas. La hemoglobina glicosilada fue clasificada en buen control (≤7%), regular control (de 7,1 a 8%) y mal control (>8%). Por medio del registro de dieta usual diaria se evaluó el patrón de consumo de alimentos, que contiene 11 criterios divididos en las siguientes categorías: mal cumplimiento (0-3 criterios), regular cumplimiento (4-7 criterios) y buen cumplimiento (8-11 criterios). Los datos obtenidos se procesaron en el programa SPSS versión 16. Se utilizó la prueba t de Student para muestras dependientes. El efecto de la intervención educativa en el control metabólico y en el patrón de consumo de alimentos se midió por medio de la prueba de McNemar con un nivel de significación del 5% para las pruebas de hipótesis.

ResultadosParticiparon 702 pacientes, con una edad promedio de 54,5±11,6 años, el 73,8% mujeres. La media de hemoglobina glicosilada inicial fue de 8,8±2,14% y al finalizar, de 7,8±1,78%, (p<0,05). Al inicio, el 23,9% de la población presentó hemoglobina glicosilada menor de 7%; al finalizar, aumentó esta proporción al 41,3%. Respecto al patrón de consumo de alimentos, la media de criterios cumplidos fue 6±3, el cual aumentó a 9±2 (p<0,000). El promedio de la hemoglobina glicosilada mostró al inicio de la intervención un comportamiento similar en las 3 categorías del patrón de consumo de alimentos, al finalizar el cambio de la hemoglobina glicosilada en la categoría de mal y regular cumplimiento fue estadísticamente significativo (p<0,022 y p<0,000, respectivamente), no así en la categoría de buen cumplimiento (p<0,065). Al finalizar la intervención, del 75,6% de la población ubicada en buen cumplimiento, el 41,3% presentó buen control metabólico (p<0,0001). Por lo tanto, mediante la prueba de McNemar se determinó que el control metabólico y el patrón de consumo de alimentos se modificaron por efecto de la intervención educativa (p<0,000).

ConclusiónLa intervención educativa tuvo un impacto positivo sobre el patrón de consumo de alimentos y el nivel de hemoglobina glicosilada, demostrando que la educación terapéutica forma parte del tratamiento de la diabetes para alcanzar los objetivos.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a metabolic disorder arising from multiple factors, and constitutes a non-transmissible chronic disease. The worldwide prevalence of T2DM is on the rise, and its complications imply important economic costs for people who suffer the disease, their families and healthcare systems, as a result of direct medical costs, and loss of work and wages.1 According to the cardiovascular risk factor monitoring survey.2 in 2014 the prevalence of T2DM in Costa Rica was 12.8%.

The causes related to this disease are complex and its complications can be prevented through healthy eating, normal blood glucose values, adequate body weight and physical activity.3 This represents one of the greatest challenges for healthcare professionals, since people with diabetes are characterized by such risky behavior as having unhealthy eating habits and/or leading a sedentary lifestyle.4

Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) reflects mean glycemia and is used as a risk marker. It is considered the gold standard for assessing glycemic control in this population.5–7 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) has established HbA1c<7% as the target for good control in most diabetic individuals.3,8

One of the key elements for improving glycemic control is nutritional therapy, since several studies have shown that it can reduce HbA1c levels by 1.0–2.0%.9 Dietary prescription should consider individual needs, the health condition, eating habits, the availability of food, and personal preferences, among other factors. It is also important to accompany nutritional therapy with an educational intervention in order for nutritional learning to have the expected effect upon metabolic control and the prevention of complications.10

Therapeutic education is considered a prevention and treatment strategy for providing diabetic individuals with the necessary tools to cope with lifestyle changes and to achieve self-control of the disease through knowledge and the acquisition of skills, while also modifying attitudes and behavior patterns in order to facilitate the active participation of patients in the control and management of their disease.11

The Nutritional Intervention in Chronic Diseases Program (Programa de Intervención Nutricional en Enfermedades Crónicas [PINEC]) was designed on the basis of this approach. Its therapeutic education methodology is group oriented, based on skills (learn to know, learn to do and learn to be) and focuses on promoting the capacity of patients to take control and responsibility of their own lives with regard to the disease.12

The PINEC is an innovative group education strategy, integrated within the medical management of diabetes, which promotes the capacity of patients to take control of and responsibility for their own lives with regard to the disease. It also allows for improving and unifying care in nutrition, by assessing the impact of the therapeutic intervention and, above all, improving metabolic control in patients with diabetes.

The program was designed to meet the standards for the development of Education Programs for People with Diabetes in the Americas in relation to the 7 diabetes behavior patterns defined by the ADA,3 within the context of therapeutic education.

It comprises 6 face-to-face group sessions held over a period of 11 months, in which active and participatory educational activities are conducted in small groups of 8–10 people with diabetes, and includes relatives as a support network for the patient, and thus also for the prevention of chronic diseases. In addition, before the educational intervention, the supervising professional conducts a reminder of the usual diet for each patient and prepares an individualized food plan in the nutrition clinic.

The sessions are organized in two blocks: a basic intensive block of three consecutive sessions (one a week) during the first month, and a maintenance block of three sessions held 2, 4 and 6 months after the start of the program, in which topics are dealt with corresponding to general aspects of the disease, such as food intake, drug treatment, cardiovascular health, body weight control and self-care. In addition, a series of teaching techniques are used such as demonstrations and dance exercises, and teaching material is used in a simple and clear manner suited to the patient and to the topic contents. In each session, a summary of the topic is provided as reinforcing material for consultation by the patient at home.

In this program, the nutrition professional has the task of guiding the diabetic subjects in relation to aspects such as the food groups that supply carbohydrates, serving sizes, meal times, and their effects upon disease control.13

According to the recommendations of the ADA,3 the educational sessions should emphasize, explain and adjust the eating plan to the needs of the diabetic subject, in order to adopt a balanced diet in terms of carbohydrates, fruit, vegetables and protein consumption, with a view to achieving or maintaining good metabolic control.

The central element of the PINEC is the nutritional aspect, with the adoption of an integral approach to treatment, prevention and the management of other disorders such as obesity, arterial hypertension and dyslipidemia. Accordingly, the objective of the present study was to determine the behavior of eating habits and HbA1c levels in people with type 2 diabetes, both at the start and at the end of the PINEC educational intervention.

Material and methodsA prospective descriptive study was carried out. The inclusion criteria were people over 18 years of age, males and females diagnosed with T2DM, seen at the nutrition clinics of the health centers of the Costa Rican Social Security system (Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social [CCSS]) during the period 2012–2016, agreement to participate in the educational intervention, and completion of the 6 sessions.

The following variables were recorded from the clinical records in order to characterize the study population: gender, age, personal disease history, the time of diagnosis of the disease, and the treatment prescribed. The body mass index (BMI), fasting glycemia and HbA1c were recorded at the first and sixth sessions.

The hexokinase method was used to determine glycemia after an 8-h fasting period. Glycosylated hemoglobin was determined based on chromatographic separation in an ion exchange cartridge. Separation was optimized to minimize interference from hemoglobin variants, labile fraction and carbamylated hemoglobin. Both parameters were obtained in the clinical laboratories of the CCSS using an automated analyzer (AU680 Beckman Coulter).

The educational sessions were held at different times depending on each health center, either in the morning at 8:00 a.m. or in the afternoon at 2:00 p.m. In these sessions, the participants measured their postprandial glucose levels two hours after the last meal (breakfast or lunch, depending on the time of the session), in order to promote self-monitoring, which was done using an Accu-Chek® Performa glucometer distributed in Costa Rica by the drug company Roche.

For the analysis of the glycemic parameters of the study population, we used the criteria of the guide for the care of people with type 2 diabetes of Costa Rica14; for fasting glycemia: good ≤120mg/dl, regular 120 to ≤140mg/dl and poor >140mg/dl; for postprandial glycemia: good ≤140mg/dl, regular 140 to <180mg/dl and poor >180mg/dl; and for HbA1c: good ≤7%, regular 7.1–8% and poor >8%.

The usual daily diet was assessed using the consumption pattern developed for the PINEC. This comprises 11 healthy eating criteria13 (breads, biscuits, legumes, milk/yoghurt, fruit, sugar source foods, vegetables, protein, lipid spreads, fries and packaged foods). For the purposes of this study, the investigators scored eating pattern as follows: poor compliance 0–3, regular compliance 4–7, and good compliance 8–11.

The CCSS protocols on patient data disclosure were followed in order to maintain participant confidentiality.

The study data were analyzed using the SPSS® version 16 statistical package. Descriptive statistics were used, with the determination of absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables, while the arithmetic mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for quantitative variables. The comparison of quantitative variables between baseline and the end of the intervention was made using the Student t-test for paired data, with a significance level of 5%.

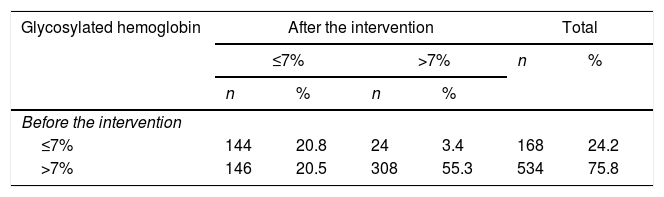

In order to assess the success of the educational intervention, an additional metabolic control category was generated (good ≤7% and poor >7%), and the food consumption pattern was analyzed with the three above established categories. The statistical analysis was performed using the McNemar test, with a significance level of 5% for hypothesis testing.

ResultsThe mean age of the 702 people included in the study was 54.5±11.6 years, and 73.8% were women. A total of 41.9% controlled the disease with mixed treatment (oral antidiabetic drugs plus insulin), 40.2% with oral antidiabetic drugs, 15.8% with insulin, and only 2.1% with diet.

From the perspective of T2DM and its comorbidities, the mean duration of the disease was 10.1±7.9 years (range 1–40 years). Three-quarters of the participants were diagnosed with arterial hypertension, and 58% had dyslipidemia; all were receiving drug treatment to control these conditions. The mean baseline BMI was 33.5±6.9kg/m2; 91.6% were overweight or obese (24.4% and 67.2% respectively). At the end of the educational intervention, the BMI was 34.3±17.1kg/m2, with no significant differences versus baseline (p<0.219). Body weight loss was 0.3kg.

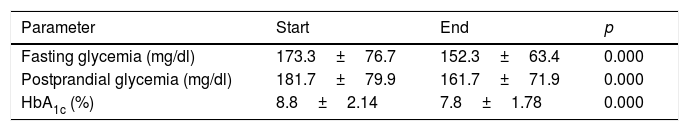

Table 1 shows the baseline and final values of the blood glucose parameters; a statistically significant decrease was observed at the end of the intervention (p<0.000).

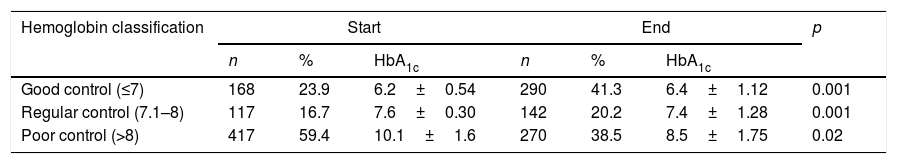

With regard to HbA1c, at baseline, 23.9% of the participants showed good metabolic control (≤7%), versus 41.3% at the end of the intervention (Table 2). The cases of regular and poor control were seen to decrease by 0.2% and 1.6%, respectively. This parameter showed statistically significant differences among the three groups at both baseline and the end of the study (p<0.000).

Mean HbA1c levels according to the classification and type of treatment at baseline and the end of the intervention.

| Hemoglobin classification | Start | End | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | HbA1c | n | % | HbA1c | ||

| Good control (≤7) | 168 | 23.9 | 6.2±0.54 | 290 | 41.3 | 6.4±1.12 | 0.001 |

| Regular control (7.1–8) | 117 | 16.7 | 7.6±0.30 | 142 | 20.2 | 7.4±1.28 | 0.001 |

| Poor control (>8) | 417 | 59.4 | 10.1±1.6 | 270 | 38.5 | 8.5±1.75 | 0.02 |

| Type of treatment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet alone | 15 | 2.1 | 7.2±2.01 | 15 | 2.1 | 7.0±1.83 | 0.73 |

| Antidiabetic drugs | 282 | 40.2 | 7.9±2.06 | 282 | 40.2 | 7.1±1.49 | 0.000 |

| Insulin | 110 | 15.8 | 9.3±2.33 | 110 | 15.8 | 8.5±1.93 | 0.05 |

| Antidiabetic drugs+insulin | 295 | 41.9 | 9.4±1.81F=32.9df=3p<0.009 | 295 | 41.9 | 8.3±1.72F=32.8df=3p<0.005 | 0.38 |

Results are reported as the mean±standard deviation.

Table 2 shows the mean HbA1c values according to the type of treatment used by the participants for diabetes control. Regarding the mean scores of this glycemic parameter, significant differences were observed among the four groups at both baseline (p<0.009) and the end of the intervention (p<0.005). Statistically significant reductions were observed only in the “antidiabetic drugs alone” and “insulin alone” treatment groups (p<0.001 and p<0.05, respectively).

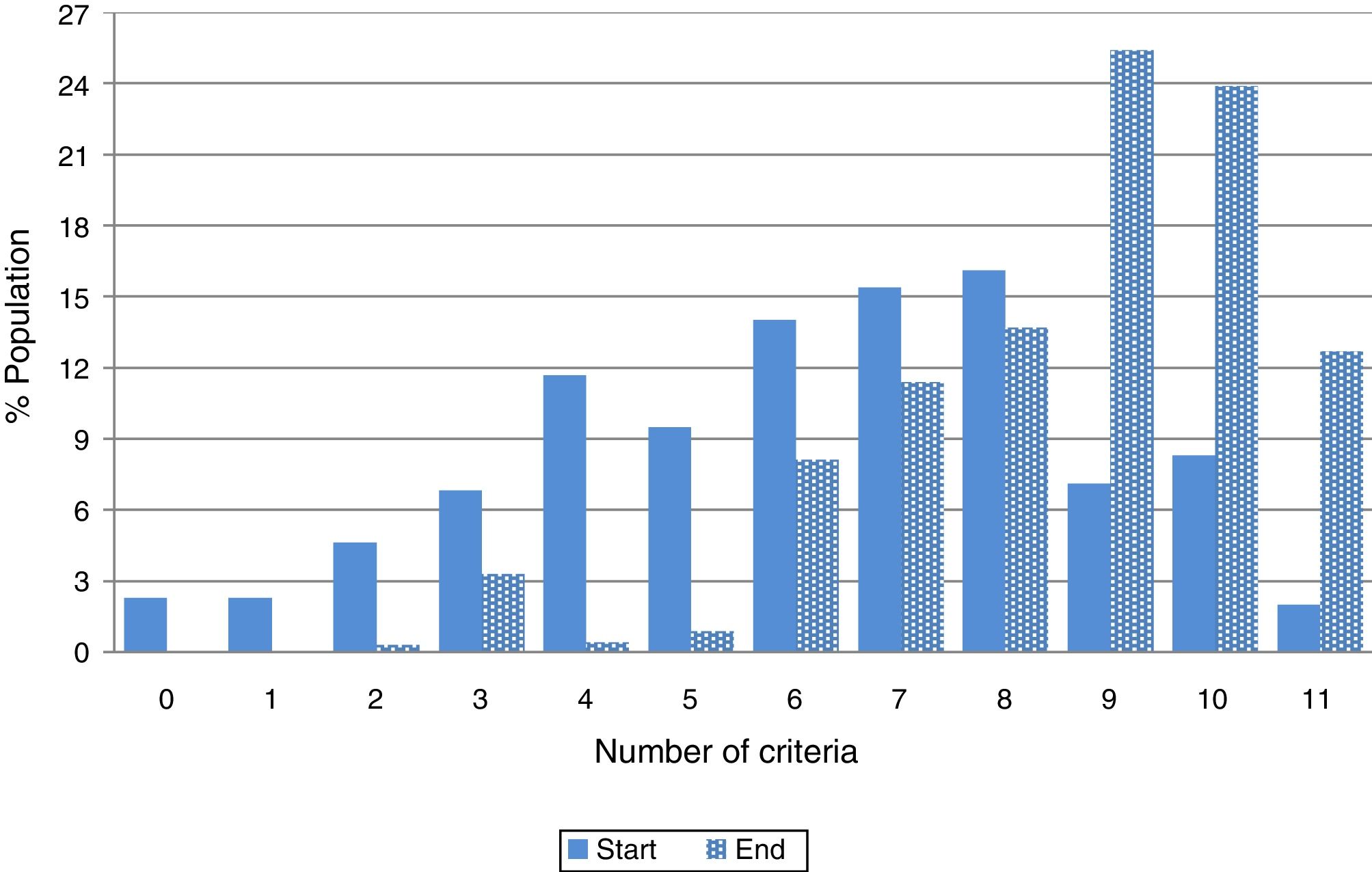

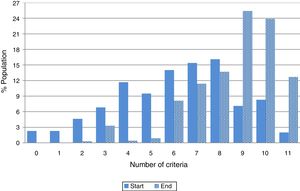

With regard to the pattern of food intake, the mean number of criteria met was 6±3 at baseline, versus 9±2 at the end of the intervention, the difference being statistically significant (p<0.000). At baseline, 2.3% of the people did not meet any criterion; 2.3% met only one criterion; and only 10% met more than 10 criteria. At the end of the educational intervention, the food consumption pattern was modified, with the total population meeting at least two criteria, while 36.6% met more than 10 criteria (Fig. 1).

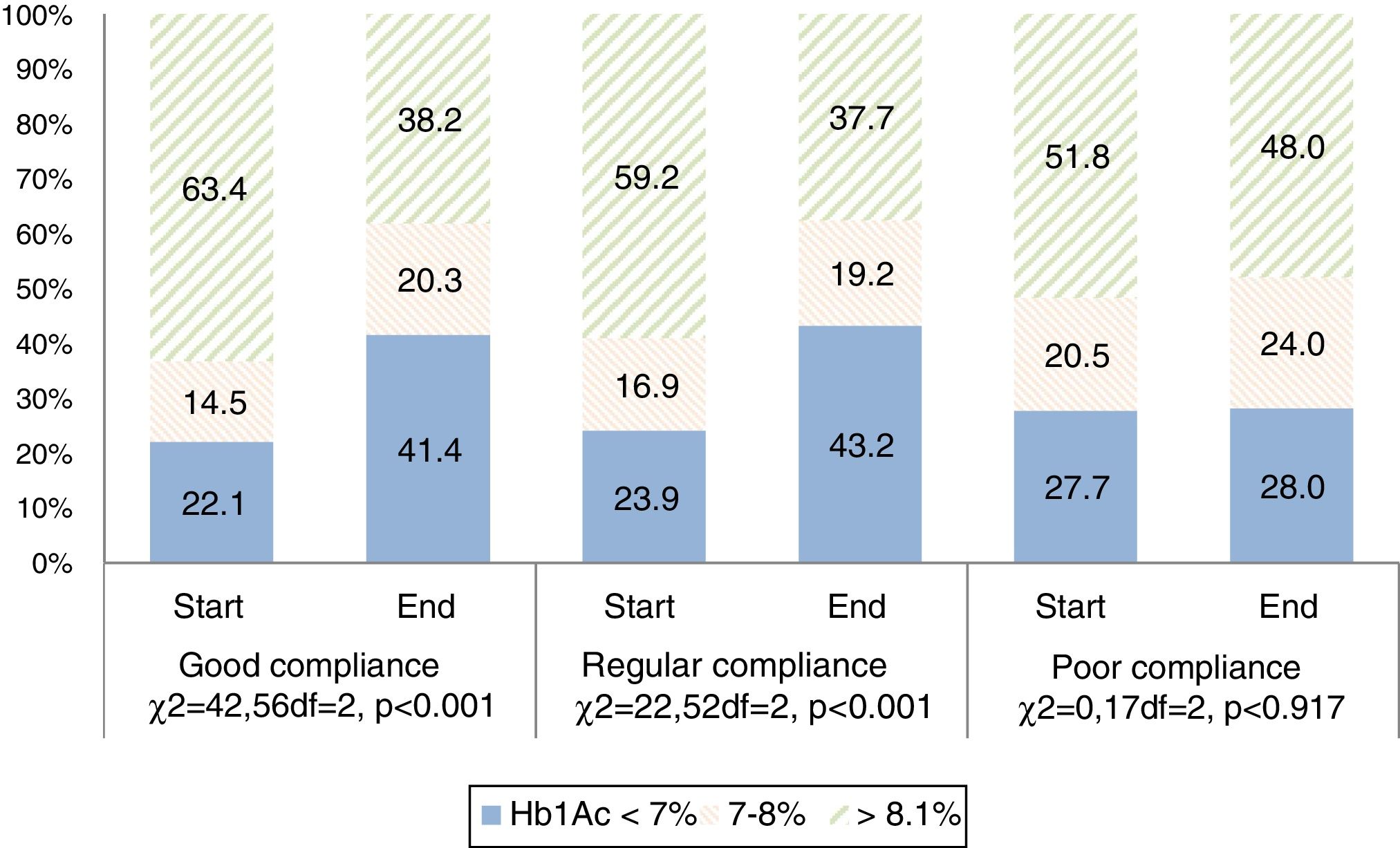

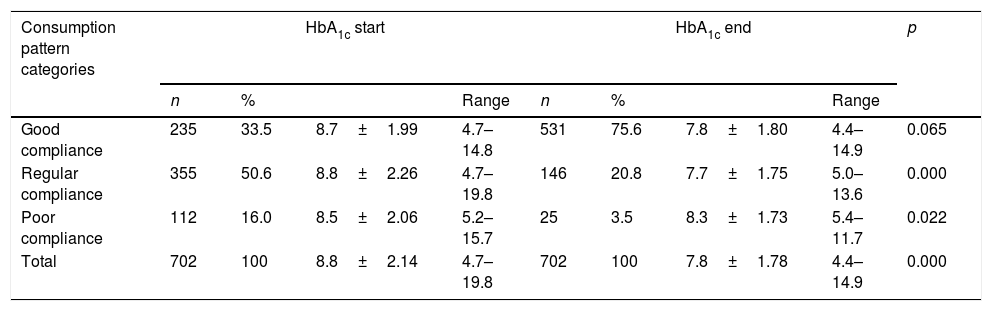

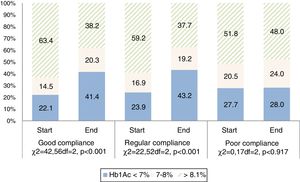

Regarding compliance with the food consumption pattern (Table 3), 16% of the participating subjects showed poor compliance (3 or fewer criteria) at baseline. This percentage had decreased to 3.5% at the end of the intervention. On the other hand, the percentage of subjects showing good compliance increased from 33.5% to 75.6%. On relating the pattern of food intake to HbA1c, the three food consumption patterns showed similar behavior at baseline, with poor metabolic control (≥8%). The change in HbA1c in the poor and regular compliance categories proved statistically significant (p<0.022 and p<0.000, respectively), though statistical significance was not reached in the good compliance category (p<0.065) (Table 3).

Mean HbA1c levels according to food consumption pattern category at baseline and the end of the intervention.

| Consumption pattern categories | HbA1c start | HbA1c end | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Range | n | % | Range | ||||

| Good compliance | 235 | 33.5 | 8.7±1.99 | 4.7–14.8 | 531 | 75.6 | 7.8±1.80 | 4.4–14.9 | 0.065 |

| Regular compliance | 355 | 50.6 | 8.8±2.26 | 4.7–19.8 | 146 | 20.8 | 7.7±1.75 | 5.0–13.6 | 0.000 |

| Poor compliance | 112 | 16.0 | 8.5±2.06 | 5.2–15.7 | 25 | 3.5 | 8.3±1.73 | 5.4–11.7 | 0.022 |

| Total | 702 | 100 | 8.8±2.14 | 4.7–19.8 | 702 | 100 | 7.8±1.78 | 4.4–14.9 | 0.000 |

Results are reported as the mean±standard deviation.

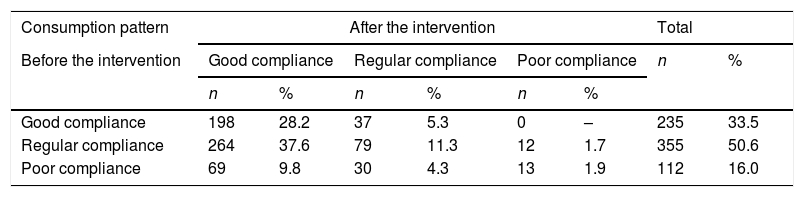

Fig. 2 shows that less than 30% of the participants in the three consumption pattern categories had good metabolic control at baseline (HbA1c≤7%). Of the participants with poor adherence to the consumption pattern at baseline, 51.8% presented HbA1c>8%. However, metabolic control improved in the good and regular compliance categories; at the end of the intervention the number of subjects with poor metabolic control was seen to have decreased, at the expense of an increase in the number of individuals with regular and good metabolic control. These data are reinforced by the McNemar test findings, which proved statistically significant (p<0.001) for both metabolic control and for the food consumption pattern (Tables 4 and 5).

Results referring to the food consumption pattern at the end of the PINEC educational intervention.

| Consumption pattern | After the intervention | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the intervention | Good compliance | Regular compliance | Poor compliance | n | % | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Good compliance | 198 | 28.2 | 37 | 5.3 | 0 | – | 235 | 33.5 |

| Regular compliance | 264 | 37.6 | 79 | 11.3 | 12 | 1.7 | 355 | 50.6 |

| Poor compliance | 69 | 9.8 | 30 | 4.3 | 13 | 1.9 | 112 | 16.0 |

McNemar test, p<0.000.

The objective of the present study was to determine the behavior of the pattern of food intake and HbA1c in people with diabetes who participated in the PINEC. The data show that an educational intervention focused on self-care had a positive impact upon these two variables.

Programmed feeding is one of the cornerstones in the management of T2DM; adequate metabolic control is difficult to achieve without it, even when antidiabetic medication is used. In many cases, it is the only adopted therapeutic measure, along with physical exercise.15 Scientific evidence suggests that there is no “ideal” eating pattern capable of benefiting all diabetic individuals. Emphasis is therefore placed on the need for an individualized nutritional strategy with no discrimination regarding the culture or the social situation of the patient. The strategy should be based on local habits and should seek to achieve healthier eating patterns.16

These aspects were considered in the PINEC. At the start, the individualized feeding plan was designed for the participants, being adjusted to their needs and habits. This contributed to making the eating pattern more consistent with the international recommendations for people with diabetes.3

In our study, the participants had a poor food consumption pattern at baseline, with a mean compliance of 6 of the 11 established healthy eating criteria. According to the data, this population had been diagnosed with the disease for several years (10.1±7.9 years on average), and in one way or another had received nutritional orientation within the public healthcare system, but no changes had been made in their eating habits. This emphasizes the fact that adherence to dietary-nutritional treatment is a complex, slow and difficult process, because it involves a change in eating habits (these being strongly rooted in people with diabetes) that requires the incorporation of new feeding regimens which need to be systematically maintained for life.16,17

Since the PINEC involved group therapy where knowledge was incorporated through active-participatory educational activities, it allowed people with diabetes to make lifestyle changes, particularly in relation to diet. At the end of the program 75.6% of the participants met more than 9 healthy eating criteria, i.e., they showed good compliance with the food consumption pattern.

Education is crucial in any action seeking to improve adherence to nutritional therapy in people with diabetes, particularly when it comes to changes in lifestyle. According to some studies, in structured therapeutic education programs using group methodology based on self-care and the empowerment of individuals, the metabolic changes achieved can be sustained or improved over the short term.12,18,19

Group interventions where education is patient-centered and not disease-centered have been shown to make a greater impact than traditional interventions, because interactive participation allows for the exchange of experiences, and the recommendations and treatments are not imposed but serve to reinforce empowerment, participation, the understanding of information, and personal satisfaction.20 In 2003, Ramírez-Sanabria et al.21 assessed the degree of satisfaction of participants in the PINEC. The active-participatory group methodology allowed the participants to change their attitude from a passive role to being responsible for their own disease through new knowledge (learn to know, learn to do and learn to be).

Guzmán-Padilla et al.22 in turn carried out a qualitative evaluation of the educational methodology of the PINEC. In their study, the participants described education as being a key element for the management of diabetes, and the topics developed in the educational interventions were perceived as allowing them to become better informed, whereas individual consultation never allowed enough time for effective education. What pleased the participants most was the group methodology, since it allowed them to share and learn from others through the exchange of experiences and the questions and doubts of their companions, and the integration of accompanying persons (particularly relatives) in the sessions, so converting the educational intervention into a support system. Another key aspect in this intervention was the perception of the facilitators as role models, generating a positive and significant influence through kindness, understanding, empathy, confidence and the concern shown to the participants.

Furthermore, Roselló et al.13 found that group educational intervention increased the consumption of legumes, fruits, vegetables and protein foods, and that a group of patients optimized their metabolic control by decreasing HbA1c. Trento et al.23 showed that group intervention exerted a greater effect in terms of the acquisition of new knowledge when the process was adapted to the needs and characteristics of the patient, independently of schooling and age. Finally, group sessions were shown to be more effective with regard to metabolic control, particularly in relation to HbA1c.

The effects of the PINEC are consistent with the results of a number of studies demonstrating the benefits of such educational interventions, showing reductions in fasting glycemia, postprandial glycemia, HbA1c and the body mass index, among other factors, thus confirming that these strategies are favorable for metabolic control in people with diabetes.21–28

In the study carried out by Carral et al.,16 on measuring adherence to the Mediterranean diet using a 14-item questionnaire, the mean score was found to be 9±2 points, and 59% of the patients had a score of 9 points or less. In other words, most patients showed a low adherence to the traditional Mediterranean diet. Blázquez et al.29 documented poor compliance with the recommendations referring to the daily intake of foods at the base of the diet pyramid. This is in contrast to the results of our study, where 16% of the subjects showed non-compliance with the food consumption pattern at baseline, followed by a decrease in this percentage at the end of the intervention.

As mentioned above, HbA1c concentration has been the gold standard for assessing glycemic control and treatment efficacy. The relationship between HbA1c and the complications of diabetes is continuous; accordingly, a decrease in HbA1c is likely to reduce the risk of complications.30 The mean HbA value1c of our study at baseline was 8.8±2.1%. At the end of the intervention, this parameter showed a statistically significant decrease of 1%, which is consistent with the data of other studies31,32 where individuals underwent educational processes and achieved an HbA1c reduction of up to 0.44% at 6 months, like that described by Steinsbekk et al.33 However, these results show that the improvements achieved in interventions are only short-term (not exceeding 12 months).

In our study, a significant decrease was observed in fasting and postprandial glycemia at the end of the intervention, thus meeting the objectives of T2DM therapy according to the international standards3 and the PINEC.

However, 38.5% of the subjects maintained HbA1c values >8%; this may be because initially the values of this parameter were three times greater than the desired level according to the ADA.3 It is important to take into account that the progressive nature of T2DM makes it difficult to maintain metabolic control over time in many patients, despite lifestyle interventions and drug treatment. Further changes are required in these cases.8,16

ConclusionsThe educational intervention had a positive impact upon the food consumption patterns and HbA1c levels of the participants.

Regardless of whether people with diabetes have a good or poor food consumption pattern, there always will be patients with HbA1c outside the desired ranges.

It is important to carry out studies to identify the factors that have the greatest impact upon this parameter, in order to develop strategies aimed at improving compliance with the therapeutic objectives.

As a structured program, the PINEC represents a redefining of functions and procedures in the context of the transition from individual to group care in the nutrition clinic.

The PINEC provides a comprehensive response to the needs of people with diabetes in the public health system of Costa Rica, beyond medical consultation. For this reason, it was taken as a basis for care and education in non-transmissible chronic diseases in the CCSS.

Financial supportThis study received public funding from the Government of Costa Rica.

AuthorshipThe authors declare that they have all fully contributed to the preparation of the present article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Roselló Araya M, Guzmán Padilla S. Comportamiento del patrón de alimentación y de la hemoglobina glicosilada en personas con diabetes tipo 2, al inicio y final de una intervención educativa. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2020;67:155–163.