Diabetes mellitus presents high prevalence, severe complications, clinical repercussions, costs and occupational implications. Their assessment requires the use of the medical history and support questionnaires.

A literature review was conducted on the topic of clinical and occupational evaluation aspects of diabetes; the database searched was Medline. The search showed numerous papers about diabetes clinical and therapeutic aspects as well as social or public health aspects but the results lacked occupational aspects. To assess the disease, the use of questionnaires is generalized and each author selects those which fit best to their purpose.

It is concluded that to carry out a clinical and occupational evaluation related to diabetes, an inter-specialities cooperation, based on a complete medical history including occupational risk factors, is recommended. The questionnaires are useful, adapted to the objective, recommending those valued in Spanish as in Fear of hypoglycemia questionnaire (EsHFS) and Diabetes-related quality of life questionnaire (EsDQOL).

La diabetes mellitus presenta elevada prevalencia, complicaciones severas, repercusión clínica, costes e implicaciones laborales. Su valoración requiere el uso de la historia clínica y cuestionarios de apoyo.

Se revisa en Medline la bibliografía sobre diabetes y la experiencia de los autores en valoración clínico-laboral, con resultados que muestran cuantiosas publicaciones en aspectos clínicos y terapéuticos relacionados con diabetes o con aspectos sociales y de salud pública, pero reducida en aspectos laborales. El uso de cuestionarios para valoración de la enfermedad es generalizado y cada autor debe seleccionar el que mejor se adapte a sus objetivos o experiencia.

Se concluye que, para la valoración clínica y laboral en diabetes se recomienda la colaboración interespecialidades, partiendo de una historia clínica completa que incluya los riesgos del trabajo. Son de ayuda los cuestionarios, adaptados a objetivo, recomendándose los validados en español como Encuesta sobre el miedo a la hipoglucemia (EsHFS) y Calidad de vida relacionada con la diabetes (EsDQOL).

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is considered a pandemic, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 415 million people in 2015, a figure that is expected to reach 642 million by the year 2040.1 In Spain, according to data from the di@bet.es study, DM affects 13.8% of the adult population, although 6% are unaware of the fact.2

The importance of the disease is both medical and economic. The estimated costs of DM vary among the different publications: recent reviews place the total cost in Spain at between 758 and 4348€ per person per year, while in the concrete case of type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM1) the figure is between 1262 and 3311€ per person per year, and for type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) between 381 and 2560€ per person per year.3

The associated labour costs are a more complex issue. According to a study conducted in Spain, 1,631,573 temporary disability (TD) processes for all diseases were recorded in 2011, with 71,401,033 days of work lost. Diabetes and its complications accounted for 0.16% of the total processes and 0.22% of the work days lost, with an estimated overall minimum cost (Spanish national minimum salary) of 3,297,095€ (141€ per person per year).4

In terms of occupational health, diabetes may lead to limitations in the work capacity of the affected individual, or may constitute a specific risk factor for occupational accidents and non-traumatic damage. This potential increase in damage risk is related to the limitations imposed by the disease due to its complications and related to its treatment.5

Adequate diabetes education to ensure correct treatment and control allows diabetics to maintain their work activity, with eventual TD periods in the event of acute complications or decompensation episodes. The chronic complications of the disease often lead to prolonged periods of TD, or even to permanent disability (PD).6

Spanish occupational prevention regulations, as reflected in Law 31/95,7 contemplate adaptive options for working individuals considered to be “particularly sensitive” due to chronic conditions which, like diabetes, cause limiting complications over time.

An important feature of occupational medicine consists of determining the highest risk positions for working individuals with diabetes (posing potential hazards for themselves or for others). Jobs with irregular working hours, circumstances causing acute complications (hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia), and chronic complications over time with possible work limitations should be taken into consideration.8

The preventive focus of occupational medicine and collaboration with public health in relation to the abovementioned aspects has led to predictive initiatives (for example, the hyperglycemia nomogram) being used for early detection, in order to optimize resources and to avoid or delay ulterior complications, which may have health, occupational and social consequences.9

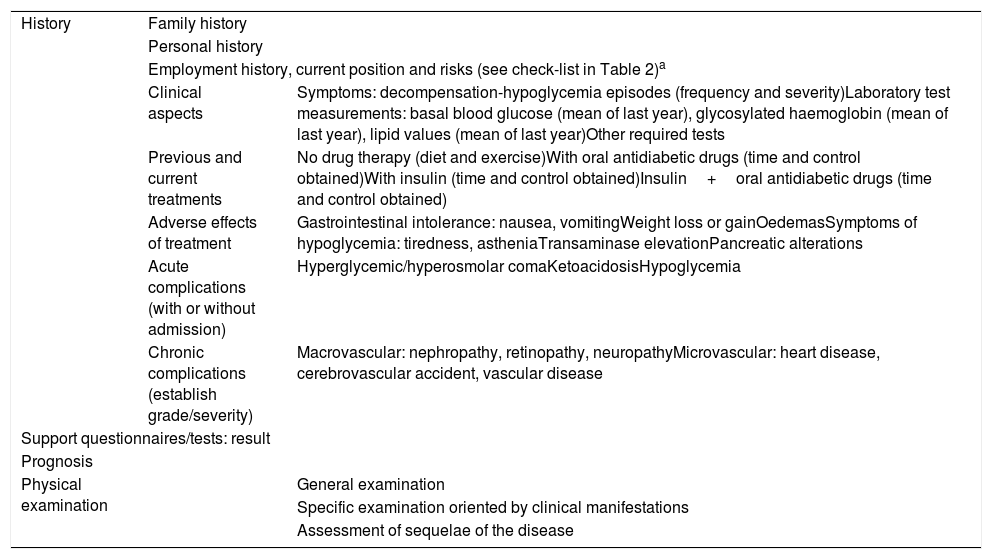

In occupational health, the clinical dimensions referring to the diagnosis, treatment and control of the disease are important, as is the compatibility of the disorder with risk-free work activity on the part of the patient. In this respect it is essential to assess occupational aptitude based on a full clinical history (Table 1), where the use of support questionnaires may be very useful, together with the evaluation of occupational risk (see the check-list in Table 2).

Clinical history in diabetes: basic data.

| History | Family history | |

| Personal history | ||

| Employment history, current position and risks (see check-list in Table 2)a | ||

| Clinical aspects | Symptoms: decompensation-hypoglycemia episodes (frequency and severity)Laboratory test measurements: basal blood glucose (mean of last year), glycosylated haemoglobin (mean of last year), lipid values (mean of last year)Other required tests | |

| Previous and current treatments | No drug therapy (diet and exercise)With oral antidiabetic drugs (time and control obtained)With insulin (time and control obtained)Insulin+oral antidiabetic drugs (time and control obtained) | |

| Adverse effects of treatment | Gastrointestinal intolerance: nausea, vomitingWeight loss or gainOedemasSymptoms of hypoglycemia: tiredness, astheniaTransaminase elevationPancreatic alterations | |

| Acute complications (with or without admission) | Hyperglycemic/hyperosmolar comaKetoacidosisHypoglycemia | |

| Chronic complications (establish grade/severity) | Macrovascular: nephropathy, retinopathy, neuropathyMicrovascular: heart disease, cerebrovascular accident, vascular disease | |

| Support questionnaires/tests: result | ||

| Prognosis | ||

| Physical examination | General examination | |

| Specific examination oriented by clinical manifestations | ||

| Assessment of sequelae of the disease | ||

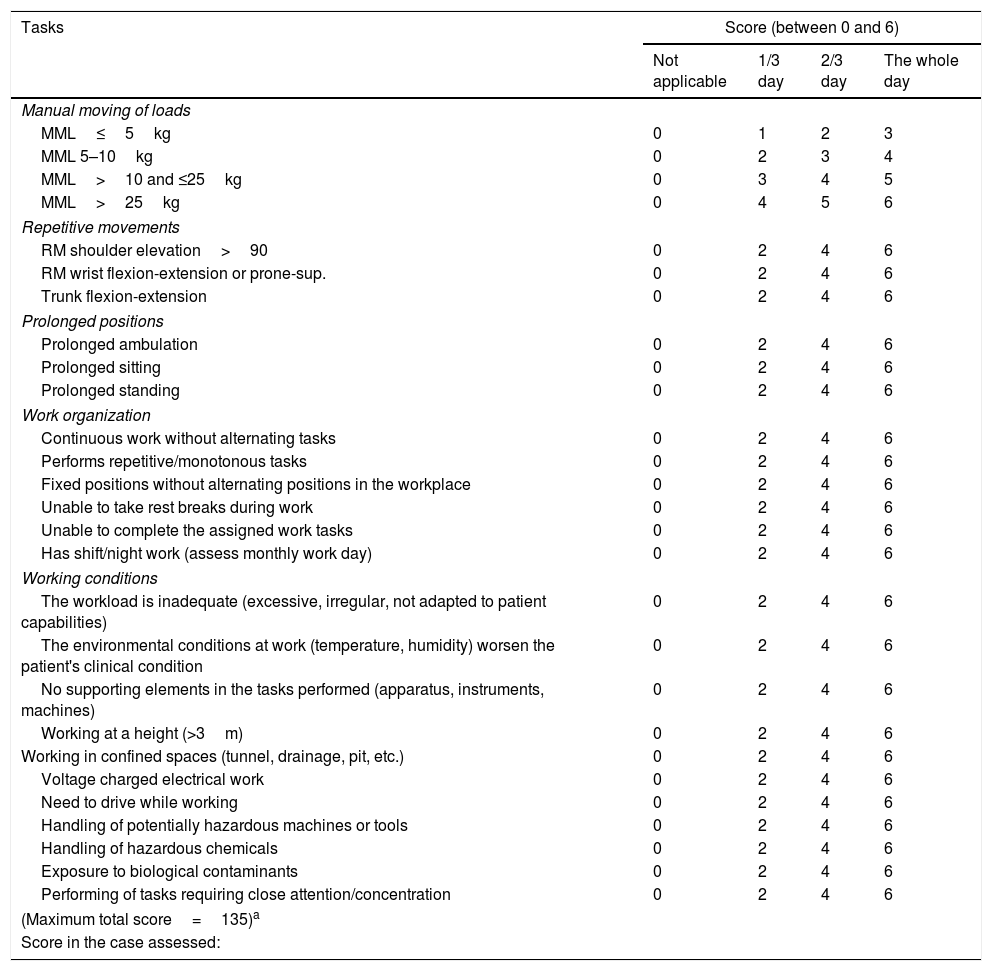

Check-list, employment status.

| Tasks | Score (between 0 and 6) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not applicable | 1/3 day | 2/3 day | The whole day | |

| Manual moving of loads | ||||

| MML≤5kg | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| MML 5–10kg | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| MML>10 and ≤25kg | 0 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| MML>25kg | 0 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Repetitive movements | ||||

| RM shoulder elevation>90 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| RM wrist flexion-extension or prone-sup. | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Trunk flexion-extension | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Prolonged positions | ||||

| Prolonged ambulation | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Prolonged sitting | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Prolonged standing | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Work organization | ||||

| Continuous work without alternating tasks | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Performs repetitive/monotonous tasks | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Fixed positions without alternating positions in the workplace | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Unable to take rest breaks during work | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Unable to complete the assigned work tasks | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Has shift/night work (assess monthly work day) | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Working conditions | ||||

| The workload is inadequate (excessive, irregular, not adapted to patient capabilities) | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| The environmental conditions at work (temperature, humidity) worsen the patient's clinical condition | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| No supporting elements in the tasks performed (apparatus, instruments, machines) | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Working at a height (>3m) | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Working in confined spaces (tunnel, drainage, pit, etc.) | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Voltage charged electrical work | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Need to drive while working | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Handling of potentially hazardous machines or tools | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Handling of hazardous chemicals | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Exposure to biological contaminants | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Performing of tasks requiring close attention/concentration | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| (Maximum total score=135)a | ||||

| Score in the case assessed: | ||||

In some cases, decisions regarding occupational assessment end up being settled in court. A 30-year case-law review (1979–2009) revealed 15,369 court sentences relating to diabetes, mainly referring to the assessment of PD in any of its degrees, or to a revision of the degree of patient disability. Claims referring to work accidents caused by diabetes or its complications were also qualitatively important.10

These aspects define DM as one of the disorders requiring greater attention on the part of those involved in occupational medicine, and further coordination with other specialties. Such joint action is essential in order to improve the quality of life and occupational integration of working diabetics, and to minimize the socioeconomic and occupational impact of the disease.11

The purpose of the present study was to review the most common questionnaires for assessing diabetes and their usefulness as a complementary tool in occupational medicine and public health.

Material and methodsA Medline review covering the previous 5 years (2013–2018) was made of the questionnaires and tools most commonly used to assess diabetes, and of the experience of the authors with these questionnaires in their various uses. Some of the publications considered most relevant according to the reviewed authors are discussed. The search keywords were: diabetes, diabetes and workplace, diabetes and quality of life, diabetes assessment and evaluation.

ResultsThe overall publications related to diabetes were numerous (447,946), with 73,590 corresponding to DM1 and 129,434 to DM2. Most of the articles focused on the various treatments and their efficacy (248,197) and on the complications of the disease (227,784), though there were also many reviews concerning DM (74,912). By contrast, few publications addressed the workplace and diabetes (271), occupational health and diabetes (1623), occupational medicine (1232), or work accidents affecting people with diabetes (77). The publications relating diabetes to disability (447,946) or public health (193,295) were more numerous.

Commented review of some publicationsDiabetes mellitus, and particularly DM2, is currently the most common chronic metabolic disease. The study of large databases allows us to explore the epidemiology of the disease, and constitutes a starting point for the design of future studies.12

The complications derived from the disease are subjected to study, particularly hypoglycemia, from both the clinical and the occupational perspective. Hypoglycemia is often associated with treatment with certain drugs and, in an active working population, it has an impact upon productivity, costs and self-care behaviour. Consequently, any intervention in this regard should have a positive effect upon work productivity and overall diabetes management.13

Hypoglycemia may cause patient insecurity and fear, and this in turn may increase occupational risk, especially in specific job positions.

Some authors have quantified this fear using the original Hypoglycemia Fear Survey (HFS), with its version translated into Spanish (EsHFS). Its viability, reliability (Cronbach's alpha), and content validity (correlating the EsHFS to the Diabetes Quality of Life [EsDQoL] scale) have been confirmed. This Spanish version has good psychometric properties and may be a useful tool for assessing the fear of hypoglycemia in Spanish-speaking patients with DM, particularly DM1.14

Other studies have assessed the psychometric characteristics of the HFS-II version and endorse it as a reliable and valid measure in adults, particularly in cases of DM1.15 This questionnaire has also been validated in other countries such as Singapore for use in people with DM1 and DM2, revealing a good content, concurrent and discriminant validity, and reliability.16

Swedish authors have conducted studies on the fear of hypoglycemia in people with DM1, focusing on general and occupational aspects using the Work Hypoglycemia Fear Survey subscale, the Worry subscale and the Aloneness subscale. Fear of hypoglycemia was shown to be more prevalent in women, with different patterns between genders regarding the factors associated with fear of hypoglycemia. The frequency of severe hypoglycemia was identified as the most important factor associated with fear.17

In some cases, intensive therapy with insulin and multiple doses in people with DM1 is associated with an increased risk of hypoglycemia episodes, and when this practice proves repetitive it lowers patient capacity to recognize the symptoms of hypoglycemia and predisposes the patient to severe episodes with important occupational risks. In this context, it is crucial to work with specific questionnaires to diagnose and deal with this problem. Catalan authors have addressed this issue through psychometric analysis of the Spanish and Catalan versions of the questionnaire developed by Clarke et al. The results showed good psychometric properties and defined both versions as useful tools for assessing knowledge of hypoglycemia in people with DM1.18

The revised form of the Diabetes Self-Care Inventory (SCI-R) has been validated in its Spanish and Catalan versions for assessing the degree of adherence to self-care in adults with diabetes. Both versions show good psychometric properties and may be considered useful tools for evaluating self-care behaviour in patients with DM1 or DM2. However, the authors point out that there are still some subgroups of patients with DM2 in which the validity of this instrument requires additional evaluation.19

The most numerous studies are those referring to quality of life, where the burden of self-control places great demands upon the individual. However, this concept remains ambiguous and is poorly defined. It is therefore important to clarify how to measure quality of life, what instruments are used for research of the disease, and how to select measures appropriately. A review conducted between 1995 and 2008 stressed that of the 10 most widely used instruments for assessing quality of life, only three did so reliably: the generic quality of life tool of the World Health Organization (WHOQoL), the Diabetes Quality of Life Measure (DQoL), and the Audit of Diabetes-Dependent Quality of Life (ADDQoL). Seven instruments were seen to more accurately measure generic health status: the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), the EuroQoL 5-Dimension (EQ-5D), the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ) and the Beck Depression Inventory ([BDI], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS], the well-being Questionnaire [W-BQ]), and Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID). This review concluded by stating that no measure can satisfy every purpose or application; it must be ensured that the instruments used are valid and reliable, since inappropriate selection and data misinterpretation will adversely affect the conclusions drawn. Quality of life assessment can identify how treatments may be adapted to reduce the burden of diabetes, and by selecting appropriate measures, robust assessments can be made.20

Similarly, other reviews have found evidence that the ADDQoL, Diabetes 39 (D-39), the Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS), the Diabetes Health Profile (DHP1/18), the Diabetes-Specific Quality of Life Scale (DSQoLS), the Elderly Diabetes Burden Scale (EDBS) and the Revised Questionnaire on Stress in Diabetes (QSD-R) have adequate psychometric properties, and recommend research to examine the effect of ethnicity and to determine the validity of these scales in developing countries.21

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) assessment is used to measure the overall impact of disease upon the life of the patient, particularly in relation to chronic disorders; hence the interest in describing and analysing the main instruments used to assess HRQoL in diabetic individuals.

A review conducted in Brazil assessed several questionnaires: generic instruments such as the Quality of Well-being Scale (QWB), the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and EQ-5D; and specific instruments such as the Diabetes Care Profile (DCP), the DQoL, the Diabetes Impact Measurement Scale (DIMS), the Diabetes Scale Assessment (ADS), ADDQoL, DHP-1 and DHP-18, QSD-R, the Diabetic Well-being Enquiry for Diabetics (WED), DSQoLS, D-39, and Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID). The results of this review showed the generic and specific instruments to have both strengths and deficiencies in assessing HRQoL in people with DM. The combined use of generic (such as the SF-36) and specific tools (such as the PAID) appears to be a consistent strategy for assessing HRQoL in DM, and underlines the urgent need for validation studies of such instruments.22

Several HRQoL measures specifically designed for people with DM can be found in the literature. The selective review studies of 12 measures that address this important construct recommend the following instruments: D-39, DCP, DIMS, DQoL and DSQoLS. The following recommendations for future research are cited: increasing the diversity of samples used to develop and evaluate measures in terms of race/ethnicity, age, and gender; examining the causal relationship between diabetes self-control and quality of life using longitudinal designs; increasing emphasis on the positive aspects of the successful self-control of chronic diseases; and using quality of life measures (HRQoL) to inform empowerment relationships between physicians and patients.23

Other studies have jointly assessed quality of life and satisfaction in people with DM1 receiving different insulin regimens, recording differences in satisfaction but not in quality of life, between the different therapeutic groups.24

In order to assess the impact of treatment upon perceived health and the recognition of hypoglycemia, some studies suggest the usefulness of instruments such as the Insulin Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire and EQ-5D Gold score, and point to the need for greater emphasis on the integration of psychological support and self-control together with intensive medical management, particularly in people with DM1.25

As mentioned above, the use of quality of life questionnaires is widely featured in studies on diabetic individuals and in relation to different aspects. One of these studies makes it possible to assess whether people with DM2 treated with insulin and with self-monitoring of blood glucose enrolled in an integrated diabetes management programme are able to achieve better metabolic control with telemedicine support than with conventional support. In addition, it addresses complementary aspects such as the impact upon the cost of health care, pharmaceutical expense, and the use of blood glucose test strips. The authors of this study used the EQ-5D and EsDQoL as quality of life questionnaires, and although they did not report major improvements in quality of life with telemedicine support, they did describe the profile bias of elderly patients with “multiple morbidities” and with technological limitations.26 They recommended that these barriers be overcome, that more time be dedicated to training, and that potential technological issues be resolved. Probably, more benefits would be obtained in younger patients who are more at home in the digital world. This strategy may be particularly useful for people whose jobs make it difficult for them to attend the medical centre because of travelling obligations related to their work.

The DQoL questionnaire is used in many countries and has been validated in different languages. The short 24-item version of the Chinese DQoL was selected as the preferred version because it imposes a lesser burden on patients without compromising the psychometric properties of the instrument.27

This specific tool for diabetic patients has also been validated in a 15-item version in Malaysia (Diabetes Quality of Life-Brief Clinical Inventory [DQoL-BCI]) for use in clinical practice. Validation is thus made of the linguistic and psychometric properties of the DQoL-BCI (Malaysian version), as affording a brief and reliable tool for assessing the quality of life of people with DM2 in that country.28 This 15-question questionnaire has also been validated in Greece. The Greek version of the DQoL-BCI has acceptable psychometric properties, high internal reliability and satisfactory construct validity, allowing its use as an important tool for assessing the health-related quality of life of Greek patients.29

This questionnaire has been validated and culturally adapted for Iran, demonstrating initial feasibility, reliability and validity as a diabetes-specific quality of life measurement in that country.30

Lastly, the DQoL questionnaire has also been validated for people with DM2 in Malaysia, and is considered a valid and reliable assessment tool for adult patients with this disease.31

It is clear that questionnaires are tools used in diabetic populations for different purposes, such as the assessment of self-perceived health, physiological distress and HRQoL, as well as other characteristics such as lifestyle or drug use. Specific studies such as that published by Esteban et al. have used the 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) and the COOP/WONCA questionnaire, with results demonstrating that self-assessment of psychological health and well-being and HRQoL are poorer in patients with diabetes than in those without diabetes, particularly in women, being associated with depression, lack of exercise and obesity.32

Many studies are available in this regard. Specifically, HRQoL has been assessed by Brazilian authors such as Bahia et al. using the EQ-5D instrument in relation to the impact of severe hypoglycemia episodes upon health. The authors found a high frequency of hypoglycemia episodes, as well as the presence of severe hypoglycemia, to have an influence upon HRQoL. These data could be used for the economic analysis of treatments that may decrease hypoglycemia and therefore improve quality of life.33 The Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ) is one of the most commonly used instruments in the context of different therapies, particularly in individuals with DM1.34

The importance of action in the early stages of the disease should be emphasized, as well as the role of health promotion and primary prevention in occupational health, since DM2 is generally preceded by a prediabetic stage whose influence upon patient quality of life has not been adequately assessed. The studies carried out by Makrilakis et al. have focused on this aspect, comparing the HRQoL of people with prediabetes versus those already diagnosed with diabetes, or those with normal glucose tolerance, using the validated HRQoL-15D questionnaire. Individuals with prediabetes have a HRQoL score similar to that of healthy subjects and higher than that of people with diabetes.35

Health information for prediabetic states and people with confirmed DM2 is essential for prevention. Neumann et al. have used generic questionnaires such as the SF-36, with higher results in healthy individuals than in those with DM2. They consequently recommend the prevention of the development of prediabetic states in order to improve HRQoL and also to reduce the risk of developing DM2.36

Questionnaires have also been used to assess the influence of environmental factors upon physical activity in diabetic patients, specifically the brief quality of life version of the World Health Organization (WHOQoL-Brief). This questionnaire confirms that the functional consequences of diabetes are complex and multifactorial, and require an integrative approach to the interaction between individual and environmental characteristics, in view of the disabling nature of this disease condition.37

Diabetes is one of the greatest public health challenges in all countries. In some, such as the United Kingdom, the increase in the number of work days lost has been assessed, since people with diabetes have a 2–3-fold greater prevalence of sick leave than the general population. Occupational medicine services are a potential source of support of diabetes self-care, but only a few studies have been made which examine the relationship between work and diabetes in the United Kingdom. In one of them, Ruston et al. explored the perceptions and experiences of people with diabetes, with results that underline the need to increase awareness among employers and managers regarding the economic benefits of supporting people with this disease, in a quest to secure effective compatibility of the disease with work activity, and adaptation to its limitations.38

The increase in diabetes and cardiovascular risk is regarded as a public health challenge in the United Kingdom. Screening for diabetes and cardiovascular risk is recommended as part of routine occupational health examinations. Such preventive activity would allow us to diagnose cases that would not otherwise be detected, and to raise awareness among employers about the importance of the health of their employees.39

Redesigning the physical workplace can have an impact upon worker health and productivity outcomes. A study published by Arundell et al. supported the idea of intervention, reporting adaptive changes which included health promotion activities, such as self-monitored eating behaviour, productivity improvements and satisfaction in the workplace. All of these represent positive changes offering greater opportunities for improvement and collaboration.40

In this integrative strategy for workers, interprofessional collaboration is useful in any medical specialty, and questionnaires are helpful for decision-making from a clinical or occupational viewpoint. The choice of questionnaire should be conditioned by the objectives to be assessed on an individual basis at any particular moment, starting from a complete clinical history, which includes a basic understanding of the risks involved in the job being performed.

Conclusions- ∘

Diabetes mellitus is a common chronic condition that leads to complications with a clinical, occupational and socioeconomic impact.

- ∘

Hypoglycemia is one of the complications posing the greatest clinical and occupational risk. Patient fear can increase occupational risk in specific jobs.

- ∘

The clinical and occupational assessment of people with diabetes should be based on a clinical history as complete as possible, and complementing the data on each disease with the risks involved for the job at hand.

- ∘

Questionnaires are helpful for clinical and occupational assessment, and should be selected based on the intended objective and with maximum collaboration among the specialties involved.

- ∘

Questionnaires validated in Spanish are recommended, and the EsHFS and EsDQoL are clear examples in this regard.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Vicente-Herrero MT, Ramírez-Iñiguez de la Torre MV, Delgado-Bueno S. Diabetes mellitus y trabajo. Valoración y revisión de cuestionarios. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:520–527.