The most common causes of hypercalcemia in the hospitalized patients are malignancy and primary hyperparathyroidism.1 Multiple mechanisms underlie the hypercalcemia caused by malignancy. While bony metastasis and osteolysis lead to hypercalcemia in some cancer patients, cancer-elaborated humoral factors such as parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrp), 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol), and parathyroid hormone (PTH) result in hypercalcemia in most others.2 In most cases of humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy, a single humoral factor, most commonly PTHrp, is produced by the cancer. A case is reported here to describe concurrent PTHrp- and calcitriol-mediated hypercalcemia associated with cholangiocarcinoma.

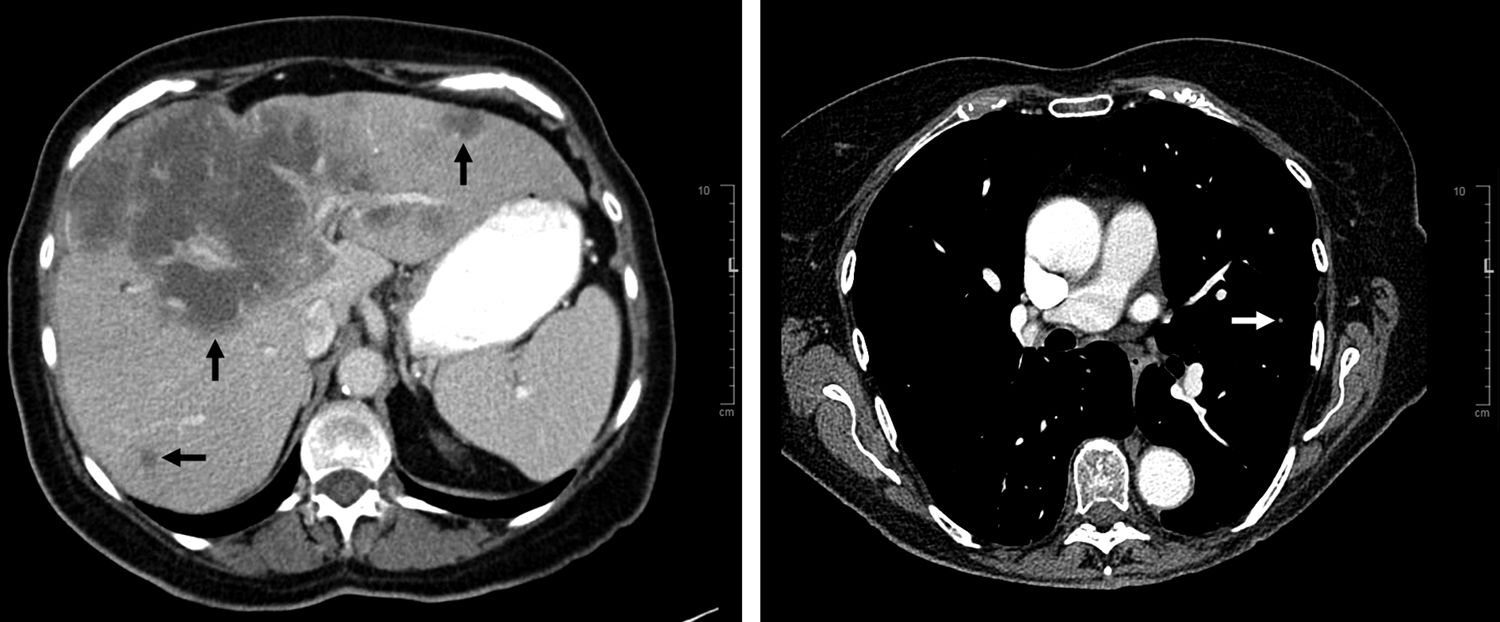

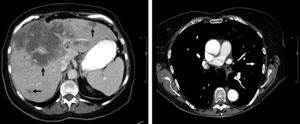

A 79-year-old female presented to our endocrine clinic for a second opinion on hypercalcemia. A month before, she had started feeling fatigued with generalized weakness, lightheadedness, urinary frequency, cough, and intermittent confusion. She went to another center for low blood pressure and was recommended to hold anti-hypertension medications. On a follow-up visit to the same hospital 4 days before presentation, she was found to have a calcium level of 13.6mg/dL (normal 8.6–10.3). A bone scan did not show evidence of bone metastases or multiple myeloma. She received intravenous fluid and was discharged while laboratory test results were pending. At the endocrine clinic, her symptoms remained unchanged. Her past medical history included hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Her calcium levels were reportedly around 10mg/dL in the previous year. The patient was retired and lived at home with her husband. She had no family history of calcium disorders. Her medications included aspirin, pravastatin, and estrogen. She had stable vital signs and used a wheelchair due to fatigue. Her mental status was grossly normal but family members noticed executive function decline and episodes of memory loss. Laboratory test results from the another center showed that PTH level was undetectable and serum and urine protein electrophoresis (SPEP and UPEP) results were normal. Repeat testing showed that calcium level was 13.2mg/dL, albumin 3.9g/L (3.9–5.0), ionized calcium 1.72mmol/L (1.09–1.29), and PTH 7pg/mL (11–51). She was admitted for hypercalcemia with subtle mental status change. Further testing showed PTHrP level was 40pg/ml (14–27), 25-hydroxyvitamin D 41ng/ml (20–50), calcitriol 87.7pg/ml (19.9–79.3), angiotensin converting enzyme <6U/L (13–69), and bilirubin 0.7mg/dL (0.1–1.2). A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed multiple irregular hypodense masses throughout the liver, the largest one measuring 14.8cm×11.2cm (Fig. 1), mild peripheral intrahepatic biliary dilation, and normal-appearing gallbladder and bile ducts. CT of chest showed scattered bilateral pulmonary nodules, largest one 7-mm (Fig. 1). A CT of the brain did not show remarkable findings. She was treated with normal saline infusion and 60mg pamidronate which normalized the calcium level (9.5mg/dL). Ultrasound-guided liver mass biopsy showed adenocarcinoma, moderate-to-poorly differentiated, favoring cholangiocarcinoma. Immunostaining of 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1-hydroxylase was not performed on the biopsied specimen. The patient was diagnosed with metastatic cholangiocarcinoma that causes concurrent PTHrp- and calcitriol-mediated hypercalcemia. She was told to avoid vitamin D supplements and sun exposure. Glucocorticoid was considered but not given due to the concern that glucocorticoid may cause immunosuppression in this patient with metastatic cancer. She was referred to receive chemotherapy.

This elderly patient with hypercalcemia and metastatic cholangiocarcinoma has suppressed PTH and no bony lesions, thus humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy is the most likely diagnosis.2 Although the acute treatment of humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy usually involves intravenous biphosphonates, the long-term treatment of hypercalcemia requires identification the specific humoral factor. If PTHrp is the humoral factor, surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiation reduce PTHrp level by reducing cancer mass; if calcitriol is the humoral factor, glucocorticoid can reduce calcitriol production by inhibiting the transcription of 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1-hydroxylase, the enzyme converting 25-hydroxyvitamin D to calcitriol.2,3 Thus PTHrp and calcitriol levels should both be tested in humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy. Usually only one of them is elevated. Very rarely, PTHrp and calcitriol can both be elevated in humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy; only a few cases are reported such as a 57-year-old male with renal cell carcinoma and a 60-year-old male with squamous cell lung cancer.4,5 This patient has elevated levels of both PTHrp and calcitriol. It is important to know that, unlike PTH, PTHrp does not upregulate the expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1-hydroxylase, thus the elevated calcitriol level in this patient must be derived from ectopic production by the cholangiocarcinoma, rather than from the physiological source, the kidneys.2,3 The case reported here supports testing both PTHrp and calcitriol levels in humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy and clearly shows that concurrent calcitriol- and PTHrp-mediated hypercalcemia can be associated with cholangiocarcinoma.

It may not be entirely surprising for cholangiocarcinoma to produce both PTHrp and calcitriol. Cholangiocarcinoma cells expresses PTHrp and cause PTHrp-mediated hypercalcemia.6,7 Although cholangiocarcinoma has not been reported to ectopically produce calcitriol, cholangiocarcinoma is known to harbor tumor-associated macrophages which can make calcitriol,3,8 and cholangiocarcinoma cells themselves may make calcitriol as well.9 It is possible that a substantial number of cholangiocarcinomas make both PTHrp and calcitriol but the elevated calcitriol levels are missed due to premature closure of diagnosis after elevated PTHrp levels are already found.

In summary, this case describes concurrent PTHrp- and calcitriol-mediated hypercalcemia associated with cholangiocarcinoma and suggests that ectopic calcitriol production may also contribute to the humoral hypercalcemia caused by cholangiocarcinoma. Furthermore, this case illustrates that both PTHrp and calcitriol should be measured in patients suspected to have humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy.