This study reviews the clinical characteristics of patients with diabetic foot ulcer treated in a Multidisciplinary Diabetic Foot Unit (MDFU) and analyzes the mortality and factors associated with its survival.

Material and methodsData from all patients who attended the MDFU for the first time for a diabetic foot ulcer during the 2008–2014 period were analized. The patients were followed until their death or until June 30, 2016, for up to 8 years.

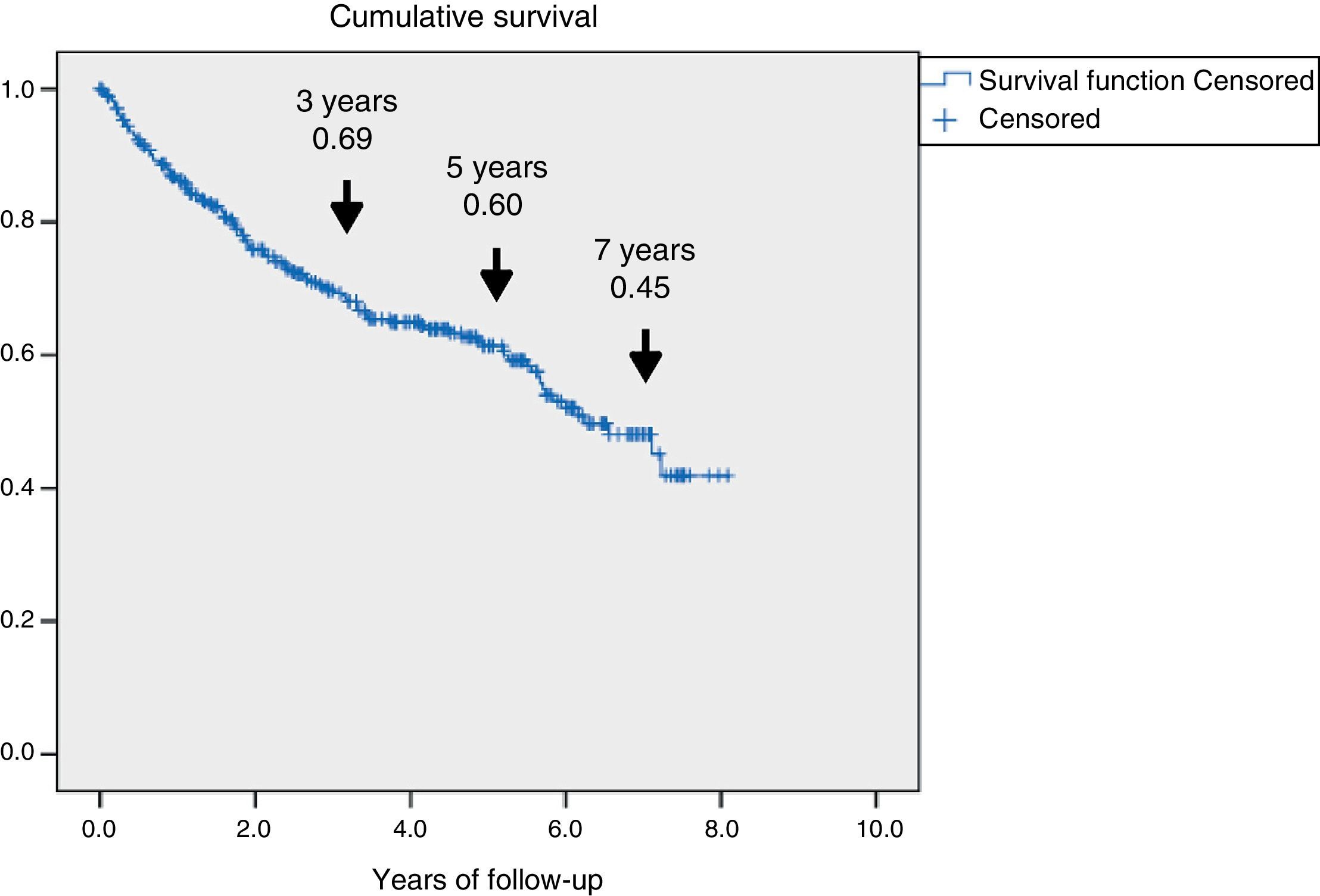

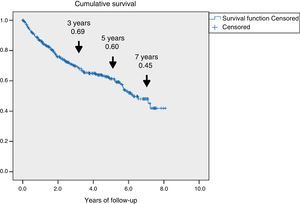

ResultsA total of 345 patients were included, with a median age (P25–P75) of 71 (61.5–80) years, and 321 (93%) had type 2 diabetes. They were characterized as patients with inadequate glycemic control, 48% had HbA1c≥8% and high prevalence of chronic complications: 60.2% retinopathy, 43.8% nephropathy and 47.2% ischemic heart disease and/or cerebrovascular disease. A total of 126 (36.5%) patients died and 69 (54.8%) were due to cardiovascular disease. Survival measured by Kaplan–Meier declined over time to 69, 60 and 45% at 3, 5 and 7 years respectively. Cox's multivariate regression analysis showed the following variables associated with mortality, HR (95% CI): age 1.08 (1.05–1.11); previous amputation 2.24 (1.34–3.73); active smoking 2.10 (1.12–3.97); cerebrovascular disease 1.75 (1.05–2.92); renal dysfunction 1.65 (1.04–2.61) and ischemic heart disease 1.60 (1.01–2.51).

ConclusionsPatients with diabetic foot ulcer are characterized by high morbidity and mortality, with cardiovascular disease being the most frequent cause of death. It is necessary to pay more attention to this risk group, tailoring objectives and treatments to their situation and life expectancy.

Este estudio revisa las características clínicas de los pacientes con pie diabético ulcerado atendidos en una Unidad Multidisciplinar de Pie Diabético (UMPD) y analiza la mortalidad y los factores asociados a su supervivencia.

Material y métodosAnálisis de los datos obtenidos de todos los pacientes que consultaron por primera vez por una lesión por pie diabético a la UMPD durante el periodo 2008-2014. Los pacientes fueron seguidos hasta su fallecimiento o hasta el 30/6/16, con un máximo de 8,1 años.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 345 pacientes, mediana (P25-P75) de 71 años (61,5-80), 321 (93%) con diabetes de tipo 2. Se caracterizaron por mal control glucémico; el 48% tenían HbA1c ≥ 8% y alta prevalencia de complicaciones crónicas: el 60,2% retinopatía, el 43,8% disfunción renal y el 47,2% cardiopatía isquémica o enfermedad cerebrovascular. Fallecieron 126 (36,5%), 69 de ellos (54,8%) por enfermedad cardiovascular. La supervivencia medida por Kaplan–Meier se redujo a un 69, 60 y 45% a los 3, 5 y 7 años, respectivamente. El análisis de regresión de Cox multivariante demostró las siguientes variables asociadas a la mortalidad con HR (IC 95%): edad 1,08 (1,05-1,11); amputación previa 2,24 (1,34-3,73); tabaquismo activo 2,10 (1,12-3,97); enfermedad cerebrovascular 1,75 (1,05-2,92); disfunción renal 1,65 (1,04-2,61) y cardiopatía isquémica 1,60 (1,01-2,51).

ConclusionesLos pacientes con pie diabético ulcerado se caracterizan por tener alta morbimortalidad; la enfermedad cardiovascular es la causa más frecuente de las muertes. Se precisa prestar más atención a este grupo de riesgo, individualizando objetivos y tratamientos a su situación y pronóstico vital.

The main factors contributing to the development of diabetic foot (DF) are diabetic neuropathy (sensory, motor, and autonomic) and peripheral artery disease. Both complications predispose to the development of lesions and tissue destruction or infection, which are the forerunners of amputations in over 85% of all cases.1 The above sequence of events (foot at risk, lesion, and subsequent amputation) has conditioned most of our knowledge in this field, the preventive strategies, and the therapeutic interventions.2 Less well-known aspects are the distinctive clinical characteristics of patients with DF, such as the increased frequency of macrovascular and microvascular complications3 and the greater patient mortality, which is estimated to be almost double that of the diabetic population without DF,4 with a 50%–60% decrease in 5-year survival.5

Different scientific position statements—those of the ADA, NICE and IDF—have clearly established the guidelines for the management of patients with DF and of those at a high risk of ulceration.6–8 Care should be provided by multidisciplinary teams comprising different specialties: podiatry, surgery, internal medicine, and endocrinology, among others. However, this approach, as well as the organization of these teams, is mainly aimed at preventing lesions and optimizing the treatment of complicated DF.9

Knowledge of patient comorbidities from a more global perspective is useful not only to provide optimum treatment, but also to allow for improved decision making according to the vital prognosis.10 On the other hand, knowing why these patients have a higher mortality rate and what the factors are that condition survival would allow for more realistic expectations and control goals. This is all the more important considering the scant interest in DF shown by endocrinologists.11

In 2008, a clinic attended by an endocrinologist and a podiatrist for the care of patients with DF was opened at the Príncipe de Asturias University Hospital (Madrid, Spain). The coordination of different disciplines was gradually established, eventually giving rise to a Multidisciplinary Diabetic Foot Unit (MDFU) involving different specialties: vascular surgery, general surgery, vascular and interventional radiology, orthopedic surgery, infectious diseases, and physical medicine and rehabilitation.12

This study reviews the clinical characteristics of the patients with ulcerated DF seen at the Unit, and analyzes the mortality of patients monitored from their first consultation, together with the factors associated with their survival.

Patients and methodsA retrospective, observational study was made of the data collected from all the patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) first attending the MDFU for a DF lesion. Patients were enrolled from 1 February 2008 to 31 December 2014. All patients were followed up until death or the last date for which data could be obtained from the electronic case history. The last registration date was 30 June 2016.

Operation of the Multidisciplinary Diabetic Foot UnitPatients with DF were preferentially referred to the DF clinic from any primary or specialized care center or emergency room. The diagnostic and management approach was decided upon at the DF clinic following the International Diabetic Foot Consensus guidelines,8 and coordination with other specialties was established as required. Patients were preferentially referred to the departments of general and vascular surgery on an outpatient basis or for admission to hospital. Regardless of whether hospital admission or assessment by other specialties was required or not, all patients were monitored at the DF clinic until the end of the episode, to optimize and coordinate the control of blood glucose and comorbidities. Once the lesion had healed, the need for regular control visits to the MDFU was assessed, based on the risk of reulceration.

Health catchment area of the Multidisciplinary Diabetic Foot UnitThe catchment area of the MDFU initially corresponded to a large urban municipality (Alcalá de Henares, Madrid) and 12 near-lying localities. During the study period (2008–2014), the population decreased from 362,785 to 248,673 inhabitants. This decrease in the reference population was attributable to the opening of a new hospital, with the population being distributed between the two centers.

Data collection and processingThe clinical characteristics of the patients were collected from a database specifically designed for the follow-up of patients at the MDFU. For those patients lost to regular follow-up at the clinic, data were obtained through the HORUS platform, in order that their current condition could be assessed. This platform allows access to primary care electronic case histories, as well as to the reports of the hospitals of the Madrid Health Service (SERMAS), and is shared by the entire Community of Madrid.

The following terms were used: renal dysfunction, determined by the presence of albuminuria >30mg/g, creatinine in first morning urine (at least 2 measurements), or the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (estimated from the MDRD-4 equation) <60mL/min; sensory neuropathy, defined as the absence of sensitivity with monofilament (10g) or tuning fork (64–128Hz). If there were multiple lesions, only the most severe was described. Ischemic lesion was defined as the absence of distal pulses or confirmatory diagnostic tests: the ankle-brachial index <0.9, the toe-brachial index <0.6, or transcutaneous oxygen pressure <30mmHg. Severity of ulceration was scored according to the Wagner staging system (1–5)13 and the grouped University of Texas13 classification system (1=1A, 2A, 1B, 2B; 2=3A, 3B; 3=1C, 1D, 2C, 2D, 3C, 3D), while severity of infection, was graded according to the IWGDF/IDSA criteria (0–3).14

Data on the main cause of death were taken from the clinical reports during hospital admission, or alternatively from the primary care electronic case history. If death occurred unexpectedly outside the hospital, the cause was regarded as probably cardiovascular, and was grouped together with ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and cerebrovascular disease.

Data reporting and statistical analysisQuantitative data are given as the median and range (P25–P75), and qualitative data as absolute values and percentages (%).

To determine which variables were associated with mortality, an analyisis of survival was made using univariate and multivariate Cox regression adjusted for independent variables and with the backward selection of variables. The hazard ratio (HR) (95% confidence interval [95% CI]) was used as a risk measure. The parameters found to be statistically significant in the univariate analysis were represented using the Kaplan–Meier function. Survival was estimated 3, 5, and 7 years after the first evaluation at the unit. The SPSS version 15.0 statistical package was used. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical issuesThe study was approved by the ethics committee of HUPA (reference OE 26/2015). Since this was a retrospective, observational study, patient informed consent was not requested. In some cases, patients were no longer followed-up by the MDFU or had died before the start of the study. Patient data were anonymized to preserve confidentiality.

ResultsBaseline characteristicsA total of 345 patients were enrolled, with a median (P25-P75) age of 71 years (61.5–80). Of these, 93% (n=321) had type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and 227 were males (65.8%). In most years the enrollment of new patients decreased (59, 56, 44, 57, 42, 48 and 39 subjects from 2008 to 2014).

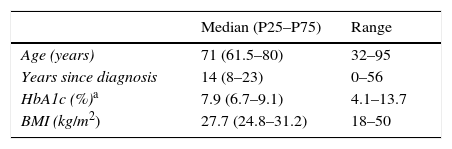

The most relevant data are shown in Table 1. Although a median of 14 years had elapsed from the time of the diagnosis of diabetes, 32 subjects (9.2%) had been diagnosed in the three years before they consulted for ulceration. Most patients (59.1%) required insulin treatment, and half of them had chronic complications: 60.2% diabetic retinopathy, 43.8% kidney failure, 39.4% ischemic heart disease, and 16.8% cerebrovascular disease. As regards blood glucose control, 165 patients (47.8%) had HbA1c values≥8%. On the other hand, 41.2% of patients had a history of previous ulceration when they first attended the MDFU, and 15.9% had suffered a lower extremity amputation.

Baseline characteristics.

| Median (P25–P75) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71 (61.5–80) | 32–95 |

| Years since diagnosis | 14 (8–23) | 0–56 |

| HbA1c (%)a | 7.9 (6.7–9.1) | 4.1–13.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.7 (24.8–31.2) | 18–50 |

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of DM | ||

| T1DM | 18 | 5.3 |

| T2DM | 321 | 93 |

| Secondary DM | 6 | 1.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Males | 227 | 65.8 |

| Females | 118 | 34.2 |

| Smoking | ||

| Never | 170 | 49.3 |

| Ex-smoker | 112 | 32.5 |

| Active smoker | 63 | 18.3 |

| Alcohol intake (♀ >25g/day, ♂ >40g/day) | ||

| Never | 250 | 72.5 |

| Prior alcohol intake | 53 | 15.4 |

| Current alcohol intake | 42 | 12.2 |

| Treatment of hyperglycemia | ||

| Without drugs for hyperglycemia control | 18 | 5.2 |

| Oral antidiabetic drugs or injections without insulin | 123 | 35.7 |

| Insulin + oral antidiabetic drugs or injections without insulin | 89 | 25.8 |

| Insulin | 115 | 33.3 |

| Prior ulceration | 142 | 41.2 |

| History of peripheral artery disease | 110 | 31.9 |

| Prior amputation | 55 | 15.9 |

| Major | 15 | 4.3 |

| Minor | 40 | 11.6 |

| Retinopathy | 201 | 60.2 |

| Severe retinopathy or macular edema requiring treatment | 96 | 29.1 |

| Kidney failure (albuminuria >30mg/g or GFR <60mL/min) | 151 | 43.8 |

| Glomerular filtration rate | ||

| GFR>60mL/min | 258 | 74.8 |

| GFR 60–30mL/min | 58 | 16.8 |

| GFR<30mL/min | 12 | 3.5 |

| Dialysis | 15 | 4.3 |

| Post-transplantation | 2 | 0.6 |

| High blood pressure | 277 | 80.3 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 136 | 39.4 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 58 | 16.8 |

| Ischemic heart disease or cerebrovascular disease | 163 | 47.2 |

| Sensory neuropathy | 259 | 75.1 |

DM: diabetes mellitus; GFR: the glomerular filtration rate.

Most lesions were superficial: 67% corresponded to Wagner stage 1, 169 were classified as ischemic (49%), and 56.6% showed some degree of infection (supplementary material, Table e-1). Of the 345 patients, 262 achieved healing of the lesion (76%), 40 required minor amputation (11.6%), 25 required major amputation (7.2%), and 18 died with unhealed lesions (5.2%).

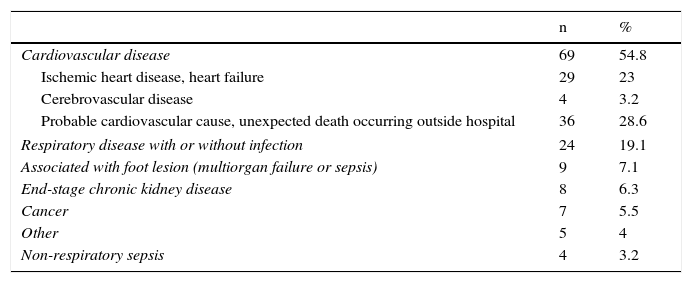

Patient follow-up and analysis of mortalityThe patients were followed up for up to 8.1 years, with a median (P25–P75) of 2.8 years (1.3–5.1). A total of 126 diabetic patients died (36.5%). Table 2 identifies the main causes of death. It is notable that cardiovascular disease was responsible for 54.8% of these deaths. In 28.6% of the cases the event was unexpected and had a rapid outcome. Hospital admission was not required. In 9 patients (7.1%), the lesion was identified as the cause of death.

Main causes of death.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | 69 | 54.8 |

| Ischemic heart disease, heart failure | 29 | 23 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4 | 3.2 |

| Probable cardiovascular cause, unexpected death occurring outside hospital | 36 | 28.6 |

| Respiratory disease with or without infection | 24 | 19.1 |

| Associated with foot lesion (multiorgan failure or sepsis) | 9 | 7.1 |

| End-stage chronic kidney disease | 8 | 6.3 |

| Cancer | 7 | 5.5 |

| Other | 5 | 4 |

| Non-respiratory sepsis | 4 | 3.2 |

Fig. 1 shows the rate of survival among the 345 patients using Kaplan–Meier curves. A progressive decrease in survival was seen (69%, 60%, and 45% after 3, 5 and 7 years respectively).

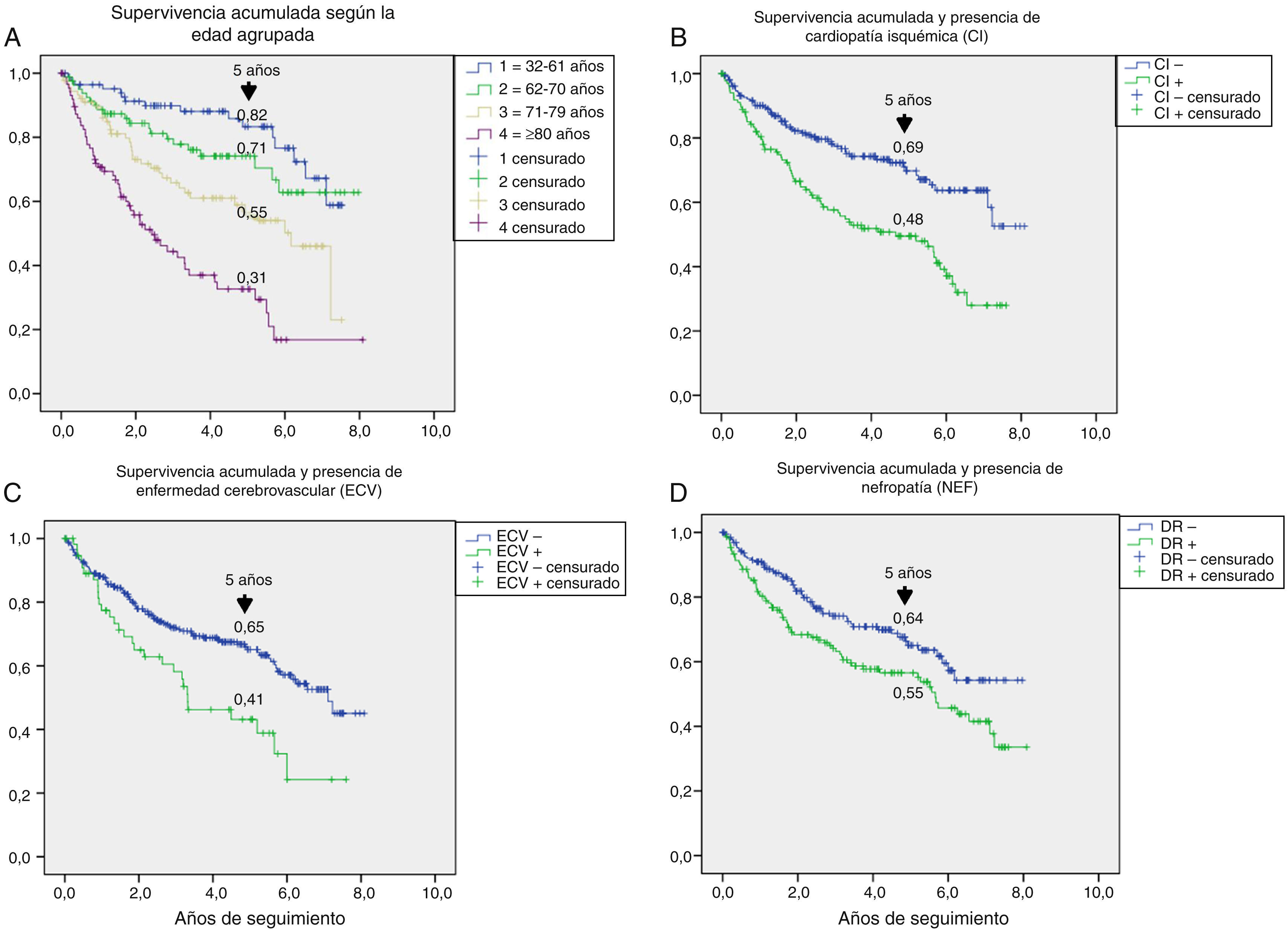

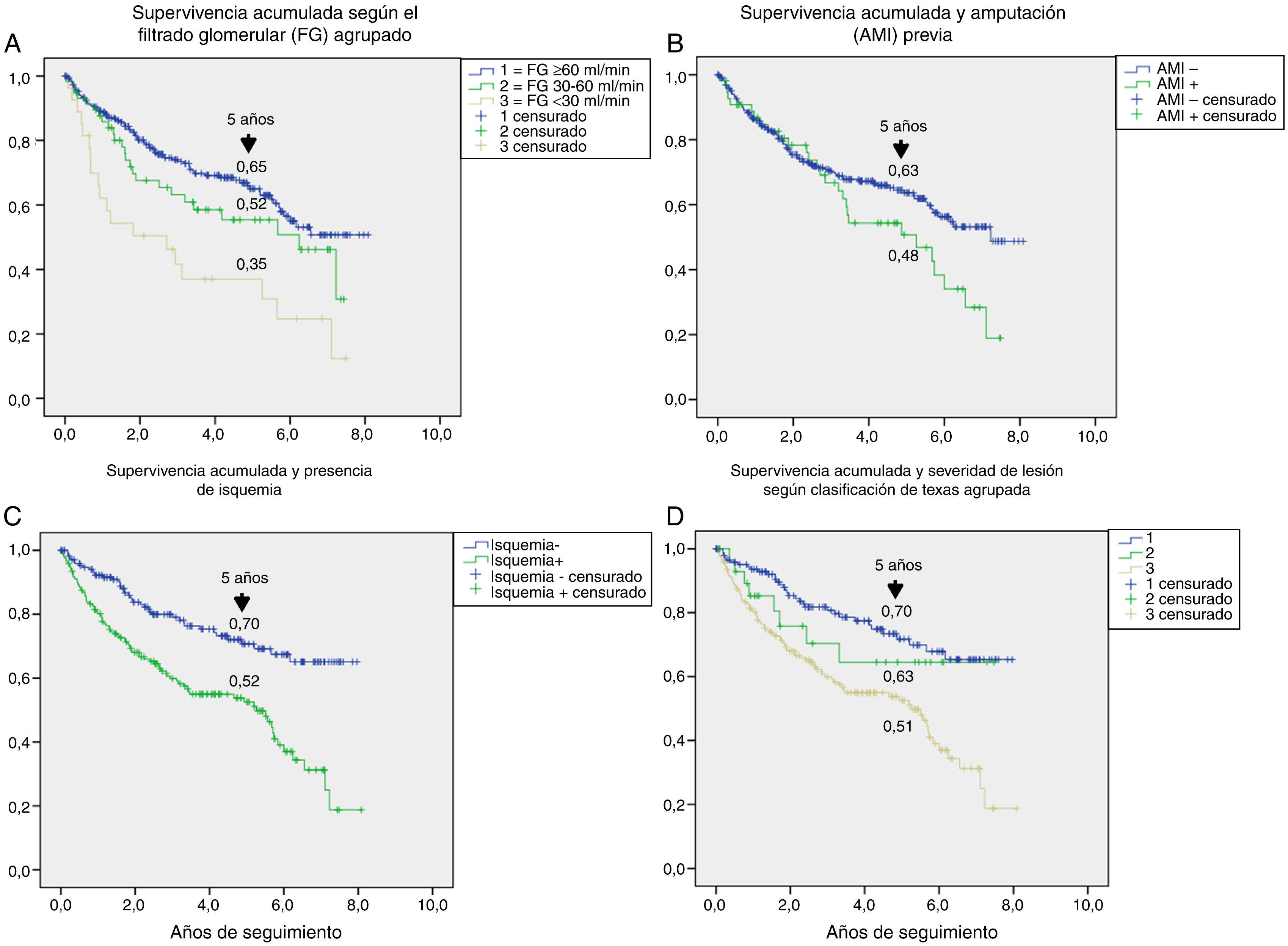

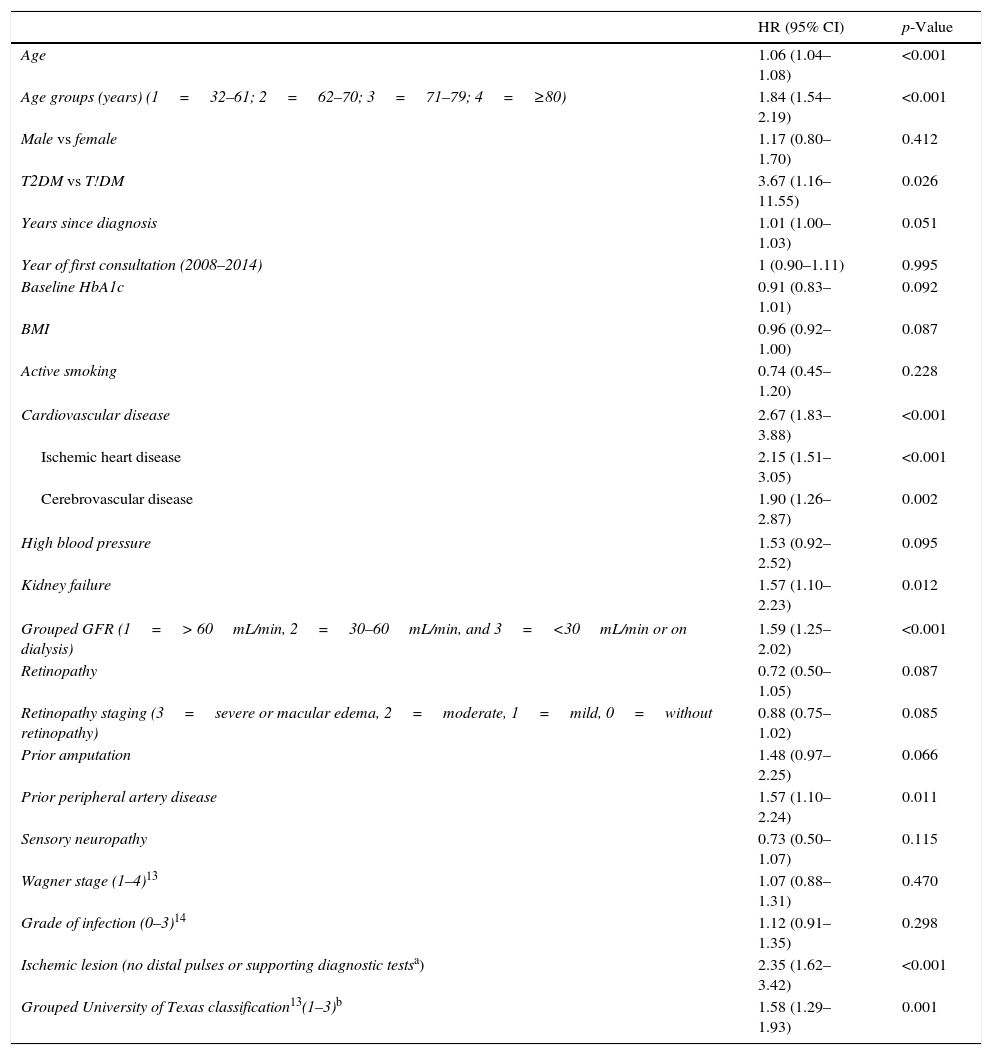

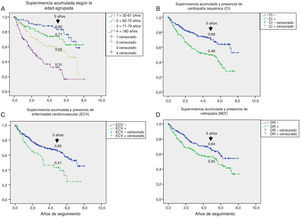

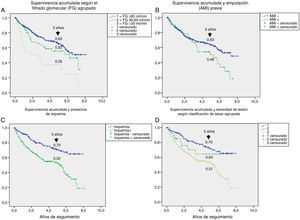

Table 3 shows the variables predicting for survival, analyzed by univariate Cox regression. Age, T2DM versus type 1 diabetes (T1DM), ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, kidney failure, GFR reduction, a history of peripheral artery disease, ischemic damage, and lesion severity (University of Texas classification) were seen to be associated with greater mortality. Figs. e-1 and e-2 (supplementary material) shows the survival curve of the significant and most representative variables, as well as the estimated 5-year survival rate corresponding to each of the survival curves. After excluding patients who died with the lesion, an analysis of the impact of lesion outcome upon mortality showed that any amputation increased the mortality risk (HR 1.66; 95% CI: 1.09–2.53; p=0.018), and if the amputation was major versus minor or the lesion healed, the HR increased to 2.25 (95% CI: 1.28–3.95; p=0.005).

Predictors of survival. Univariate analysis.

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | <0.001 |

| Age groups (years) (1=32–61; 2=62–70; 3=71–79; 4=≥80) | 1.84 (1.54–2.19) | <0.001 |

| Male vs female | 1.17 (0.80–1.70) | 0.412 |

| T2DM vs T!DM | 3.67 (1.16–11.55) | 0.026 |

| Years since diagnosis | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.051 |

| Year of first consultation (2008–2014) | 1 (0.90–1.11) | 0.995 |

| Baseline HbA1c | 0.91 (0.83–1.01) | 0.092 |

| BMI | 0.96 (0.92–1.00) | 0.087 |

| Active smoking | 0.74 (0.45–1.20) | 0.228 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 2.67 (1.83–3.88) | <0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2.15 (1.51–3.05) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.90 (1.26–2.87) | 0.002 |

| High blood pressure | 1.53 (0.92–2.52) | 0.095 |

| Kidney failure | 1.57 (1.10–2.23) | 0.012 |

| Grouped GFR (1=> 60mL/min, 2=30–60mL/min, and 3=<30mL/min or on dialysis) | 1.59 (1.25–2.02) | <0.001 |

| Retinopathy | 0.72 (0.50–1.05) | 0.087 |

| Retinopathy staging (3=severe or macular edema, 2=moderate, 1=mild, 0=without retinopathy) | 0.88 (0.75–1.02) | 0.085 |

| Prior amputation | 1.48 (0.97–2.25) | 0.066 |

| Prior peripheral artery disease | 1.57 (1.10–2.24) | 0.011 |

| Sensory neuropathy | 0.73 (0.50–1.07) | 0.115 |

| Wagner stage (1–4)13 | 1.07 (0.88–1.31) | 0.470 |

| Grade of infection (0–3)14 | 1.12 (0.91–1.35) | 0.298 |

| Ischemic lesion (no distal pulses or supporting diagnostic testsa) | 2.35 (1.62–3.42) | <0.001 |

| Grouped University of Texas classification13(1–3)b | 1.58 (1.29–1.93) | 0.001 |

GFR: the glomerular filtration rate.

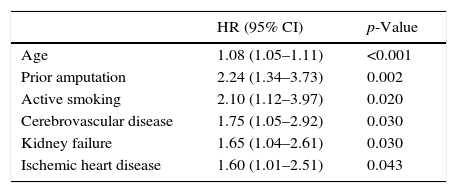

The multivariate analysis (Table 4) allowed for the adjustment of the baseline predictors of survival, and the variables independently associated with increased mortality were found to be age, prior amputation, active smoking, cerebrovascular disease, kidney failure, and ischemic heart disease.

Predictors of survival. Multivariate analysis adjusted for different variablesa with backward stepwise selection of variables.

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | <0.001 |

| Prior amputation | 2.24 (1.34–3.73) | 0.002 |

| Active smoking | 2.10 (1.12–3.97) | 0.020 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.75 (1.05–2.92) | 0.030 |

| Kidney failure | 1.65 (1.04–2.61) | 0.030 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.60 (1.01–2.51) | 0.043 |

Patient age, sex, year of study enrollment, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, high blood pressure, kidney failure, retinopathy, sensory neuropathy, lesion severity (grouped University of Texas classification), active smoking, Hb1Ac, the BMI, and a history of lower extremity amputation.

The presence of ulcers due to DF is a significant problem in patients with DM, with an estimated overall prevalence of 6.3%.15 In this study, those patients were found to have a distinctive clinical profile, with a significant decrease in their survival rate. This shorter survival was largely attributable to cardiovascular disease, resulting in an estimated 60% survival rate after five years of follow-up.

According to the literature, patients with ulcerated DF are older and have more years of disease (10 years more, on average) than patients without this complication.15 Data from this study, conducted on patients with a median age of 71 years and a time from diagnosis of DM of 14 years, agree with those found in the two largest series of patients consulting for complicated DF.16,17 It should be noted that at the time of consultation almost 10% of the patients had been diagnosed with DM less than three years previously, which is consistent with the torpid course of the main causative factor, neuropathy, which develops even in the prediabetic stage.18 Aspects such as the negative psychosocial profile of these patients19 may contribute to preclude an early diagnosis, causing them to consult at more advanced stages of the disease. This aspect may also contribute to poorer blood glucose control and to a greater frequency of complications at all levels, as has been shown both in our study and in historical series.20

These were also patients with lower body mass index (BMI) values than most subjects attending our clinic for T2DM,21 as has been reported in a recent meta-analysis.15 This finding would explain the more frequent need for insulin treatment of such patients, as they are more insulinopenic. Other larger series support these results.3,17 A particularly relevant finding was the presence of high comorbidity. Thus, 163 patients (47.2%) had ischemic heart disease or cerebrovascular disease. Even more frequent, however, was the presence of retinopathy (60.2%), which was severe in 29.1% of the cases. These findings should condition both the choice of treatment for correcting hyperglycemia and the glucose control targets. The latter should be individualized, and measures should be taken to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia.22

In agreement with other reports in the literature,4,23,24 the main cause of death in this population was cardiovascular disease, followed in order of frequency by respiratory disease. This latter observation is reasonable bearing in mind the high previous tobacco exposure rate in our series (32%) and the fact that 18.3% continued to smoke. A high prevalence of smokers is one of the distinctive characteristics of the population with ulcerated DF.15 The analysis of the causes of mortality showed that 18 patients had died with their lesions, and in 9 of these (7.1% of deaths) the lesion was identified as the mortality-triggering factor in the hospital clinical reports. Few studies have explicitly described how the lesions contribute to patient death. In one such study, Ghanassia et al. found 19% of the deaths to be associated with the lesion.23

The survival analysis (Fig. 1) showed that the survival rate decreased to 60% after five years of follow-up, which is consistent with prior reports.23–25 The mortality rate, estimated at 8%–10% at one year,5,20 has changed little in the past two decades,3 and although it differs depending on the region, there appears to be no geographical correlation26 capable of explaining these differences in terms of imbalances in the health care of these patients. Mortality was higher than reported in studies involving T2DM patients, with a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease,27 and was also greater than the mortality found in the recent cardiovascular safety analyses conducted in patients in secondary prevention, whose global mortality did not exceed 3% annually.28,29

The univariate analysis allowed us to assess the contribution of each baseline variable to the risk of death: most of them are well known5,20,25 and may be extrapolated to what can be seen in any patient with DM, such as age, the presence of macrovascular disease, kidney disease, and impaired GFR. Other variables, such as the presence of lesion ischemia (HR 2.35) and lesion severity (HR 1.58), are unique to ulcerated DF. In their classical study, Moulik et al. noted, after six years of follow-up, that mortality was greater among patients with ischemic ulcers than in those with neuropathic ulcers.30 The relationship between lesion severity and mortality has been more recently analyzed,31 with the former being described as the most relevant independent predictor of mortality, even more than cardiovascular disease.

On entering all the variables in the same equation (Table 4), those that best predicted mortality were found to be age, prior amputation, smoking, cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, and kidney failure, while ischemia and lesion severity were left out of the equation. These latter two factors may possibly give us indirect information regarding the vascular condition of the patient, the severity of multiorgan damage, and fragility.

One aspect that is not always well understood concerns the attribution of the high mortality of these patients almost exclusively to their older age. Fig. e-1 stratifies survival by age. Survival gradually decreased at five years from 82% in patients under 61 years of age to 31% in those over 80 years of age; the shorter survival in diabetic patients with ulcerated DF therefore affects all ages.

A number of hypotheses have attempted to explain the high mortality rate in these patients.31 Perhaps the most relevant hypothesis is that which relates peripheral neuropathy and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy within the same patient, a combination that results in increased myocardial ischemia as either silent ischemia or with a poorer adaptive response to ischemic insults.32,33 Consistent with this idea is the finding in this population of greater mortality among subjects with a prolongation of the QTc interval (an indicator of cardiac autonomic neuropathy) with HbA1c < 7.5% as compared to patients with higher HbA1c values.34 The presence of peripheral neuropathy is precisely the common element found to a greater or lesser degree in most patients with ulcerated DF.

Another hypothesis is that uncontrolled sepsis associated with an infected ulcer may result in increased mortality in such patients.24 However, this mechanism is only plausible if death occurs while the lesion persists, but not after it has healed. In our series this occurred in 18 patients (14.2%).

This study, intended to clarify aspects of patients with ulcerated DF, has practical implications in that it characterizes patients with a high cardiovascular risk and overall mortality. Although few studies have specifically addressed this patient population,35,36 multifactorial strategies designed to individualize blood glucose control, avoid hypoglycaemia, and intensify the control of cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. lipid profile, blood pressure, smoking), and which have been shown to be useful in DM populations with a high cardiovascular risk, could improve the survival rate of these patients. It is possibly this perspective, i.e. that of the most vulnerable patients, that should alert us to the need for closer follow-up.

The limitations of his study include:

- -

The causes of death were collected from the clinical reports and electronic case history. However, it is well known that post mortem findings are not always consistent with the clinical data.

The study had the following strengths:

- -

All the patients with ulcerated DB seen at the MDFU were enrolled, regardless of the severity of their condition.

- -

Data were collected by the professionals themselves and from a database specifically prepared for this study.

- -

The follow-up period (up to 8.1 years) was long, and therefore allowed us to obtain mid- and long-term results of care of these patients.

In conclusion, patients with ulcerated DF have a unique clinical profile characterized by many years since disease onset, poor blood glucose control, and a high incidence of microvascular and macrovascular complications. These patients also have a high mortality rate that cannot completely be accounted for by age and the coexistence of comorbidities. The variables independently associated with the survival rate include age, prior amputation, smoking, cerebrovascular disease, kidney failure, and ischemic heart disease. Closer attention to this risk group is required, with goals and treatment being adapted to the situation, and with the vital prognosis being taken into account in the decision-making process.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rubio JA, Jiménez S, Álvarez J. Características clínicas y mortalidad de los pacientes atendidos en una Unidad Multidisciplinar de Pie Diabético. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2017;64:241–249.