In severe forms of obesity there is a high prevalence of psychopathological comorbidity. Psychiatric evaluation is an important component of comprehensive obesity care and contributes to optimizing therapeutic results after bariatric surgery.

ObjectiveTo assess the effectiveness of psychometric tests used in the protocol for selecting patients for bariatric surgery.

Material and methodsRetrospective naturalistic observational study of 100 patients who were candidates for bariatric surgery. Patients who complete the psychometric protocol and the psychiatric interview between January 2019 and June 2021 are included. Two groups are formed: those considered unfit for any psychopathological reason and those considered fit. To evaluate the effectiveness of the tests used, ROC curves will be used. The sensitivity and specificity values of each test used will be obtained.

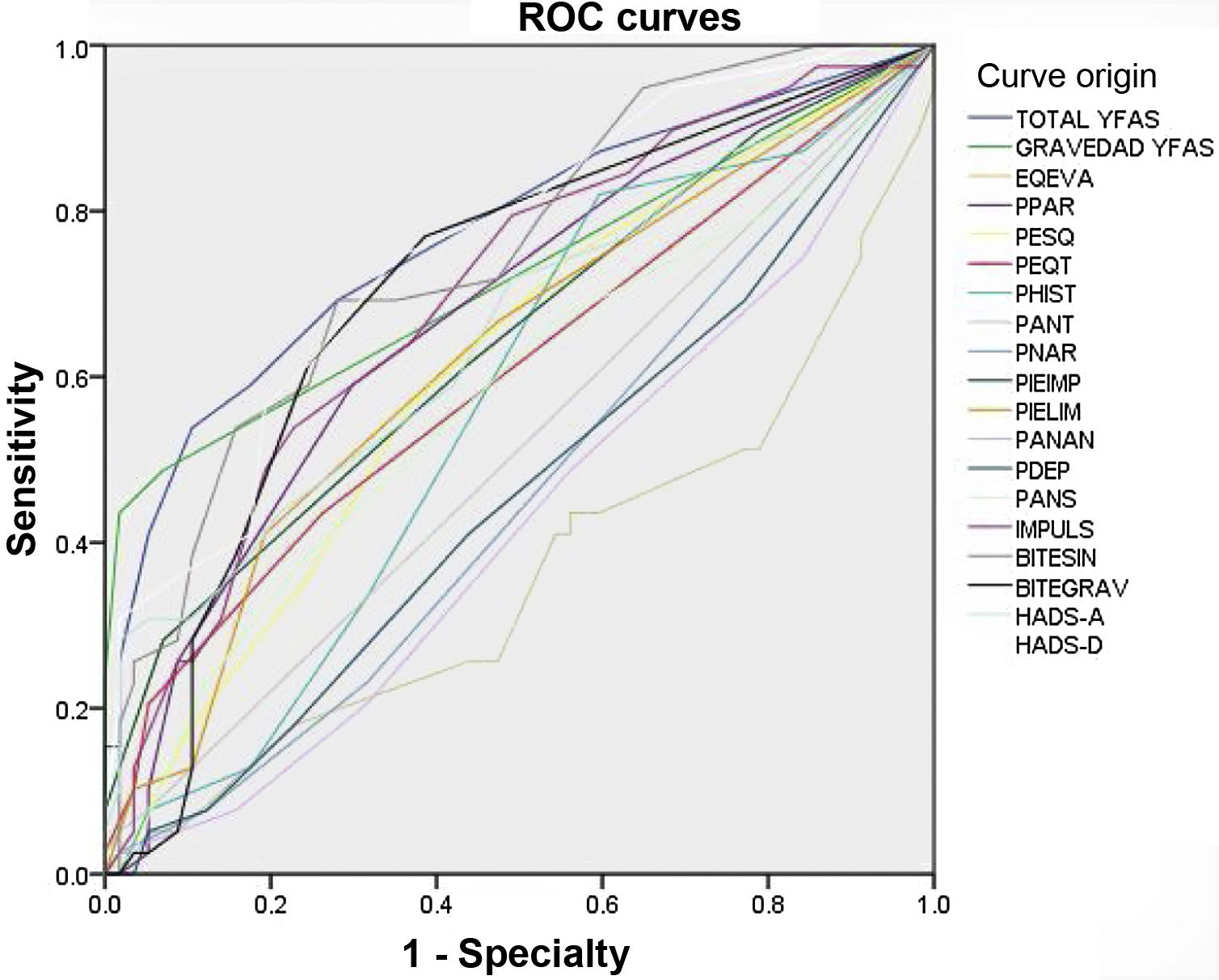

Results97 patients included, aged between 20 and 61 years, 64.9% women. 51.5% had a family history and 38.1% a personal history of any psychiatric disorder. Regarding the area under the curve, the scales that presented a value greater than 0.7 were the YFAS total score (0.771), HADS-D (0.757), the Edinburgh Bulimia total score (0.747), the severity score of YFAS (0.722) and Edinburgh Bulimia Severity Score (0.705). The most frequent diagnoses as a cause of exclusion were Food Addiction 8 (20.5%) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) 6 (15.5%).

ConclusionsThe YFAS, BITE and HADS-A scales were useful to discriminate those patients considered unsuitable for bariatric surgery for any psychopathological cause.

En las formas graves de obesidad existe alta prevalencia de comorbilidad psicopatológica. La evaluación psiquiátrica es un componente importante de la atención integral de la obesidad y contribuye a optimizar los resultados terapéuticos tras cirugía bariátrica.

ObjetivoValorar la efectividad de los test psicométricos empleados en el protocolo de selección de pacientes para cirugía bariátrica.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional naturalístico retrospectivo de 100 pacientes candidatos a cirugía bariátrica. Se incluyen pacientes que completan el protocolo psicométrico y la entrevista psiquiátrica entre enero de 2019 y junio de 2021. Se conforman dos grupos: los considerados no aptos por razón psicopatológica y aquellos considerados aptos. Para evaluar la efectividad de los test empleados se utilizarán curvas ROC. Se obtendrán los valores de sensibilidad y especificidad de cada test empleado.

Resultados97 pacientes incluidos, con edades entre 20 y 61 años, 64,9% mujeres. El 51,5% presentaron antecedentes familiares y el 38,1% antecedentes personales de cualquier trastorno psiquiátrico. Respecto al área bajo la curva, las escalas que presentaron un valor superior a 0,7 fueron la puntuación total YFAS (0,771), HADS-D (0,757), la puntuación total de Bulimia de Edimburgo (0,747), la puntuación de gravedad de YFAS (0,722) y la puntuación de gravedad Bulimia de Edimburgo (0,705). Los diagnósticos más frecuentes como causa de exclusión fueron Adicción a la comida 8 (20,5%) y Trastorno de Ansiedad Generalizada (TAG) 6 (15,5%).

ConclusionesLas escalas YFAS, BITE y HADS-A fueron útiles para discriminar a aquellos pacientes considerados no aptos para cirugía bariátrica por cualquier causa psicopatológica.

Obesity is possibly the most common metabolic disorder in the Western world. In Spain, the prevalence of obesity is 21.6% (22.8% among men and 20.5% among women), and increases with age.1 Between 1987 and 2014, the prevalence of overweight, obesity and morbid obesity increased by 0.28% per year.2 In terms of morbid obesity, there are few data in our setting. According to data from the National Health Survey, obesity was classified as morbid in 0.89% of Spanish adults in 2011/2012.3

Patients with lower grades of obesity are prescribed dietary measures, increased physical activity and certain behavioural therapies, whether or not they are associated with pharmacological treatments. Extreme or morbid obesity is often refractory to conventional treatment. Bariatric surgery is an effective and safe alternative for the treatment of morbid obesity, provided that it is performed after a careful selection of candidates, which considers the patient's biopsychosocial variables, and under strict patient follow-up.

Bariatric surgery is a valid treatment option for obesity if the body mass index (BMI) exceeds 40 kg/m2 or in subjects with comorbidities and a BMI of more than 35 kg/m2.4 For optimal results, it is important to have the participation of a multidisciplinary team that includes a doctor, a dietician, a psychologist or a psychiatrist with experience in this field, and an expert surgeon in bariatric interventions. One important part of the evaluation process is the definition of realistic expectations. Patients undergoing bariatric surgery are not likely to achieve their ideal weight. Typical satisfactory weight loss is defined as a percentage of weight loss greater than 50% of excess body weight.

The psychopathological causes that advise against bariatric surgery include any state that puts at risk the modification of habits and beliefs regarding eating behaviour that lead to weight loss and improved health, which is the goal of the surgical procedure.4

Today, obesity is not considered a mental disorder. However, there is increasing evidence of the possible existence of a certain psychopathological comorbidity. There is a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders in severe forms of obesity. Psychiatric assessment may be an important component of comprehensive obesity care and deserves further mention. This can be expected to optimise therapeutic and functional outcomes. Furthermore, as the bidirectional link becomes evident, treatment of psychiatric illness can reduce the burden of obesity and vice versa. In some cases, it is a primary psychiatric disorder that acts as a precipitant or maintainer of excess pathological weight. These include bulimia nervosa, food addiction, binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome.5,6

According to the Morbid Obesity Intervention Protocol at the Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León [León University Hospital Healthcare Complex], and due to psychopathological contraindications, psychiatric assessment of patients is necessary to exclude the following conditions:

- □

Absolute contraindications: addictions, including alcoholism, mental retardation, bulimia nervosa.

- □

Relative contraindications: clearly unfavourable family environment, psychosis, pathological personality: schizotypal, borderline and paranoid personality disorders; psychogenic vomiting; hyperphagia in other psychological disorders; severe difficulty understanding and carrying out the requirements of the procedure.

Objective: to assess the effectiveness of the psychometric tests used in the patient selection protocol for bariatric surgery.

Material and methodsThe study is a retrospective, naturalistic observational study. Approved by the Clinical Research and Ethics Committee of the León and El Bierzo Health Areas on 22 February 2022, with file number 21162. According to the protocol used to select patients for bariatric surgery, all candidates proposed by Endocrinology must complete a battery of tests and a questionnaire on sociodemographic variables during an interview with a clinical psychologist. They are subsequently assessed in a specific consultation by a psychiatrist and, after this second consultation, the patient is included in the surgical protocol or excluded from it, according to the diagnostic findings.

The battery of psychometric tests used includes:

- -

Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS)7

- -

Bulimic Investigatory Test, Edinburgh (BITE)8

- -

Plutchik's Impulsivity Scale (PIS)9

- -

Salamanca Personality Traits Questionnaire (SPTQ)10

- -

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)11

Given that the psychopathological contraindications for bariatric surgery mainly correspond to eating disorders and addictions, the BITE and the YFAS were selected. Similarly, the regulation of impulse control, personality traits, and anxiety and depression scores can be classified as relative contraindications, so it was decided to include simple tests for assessing them (PIS, SPTQ and HADS).

Inclusion criteria- -

Patients who completed the psychometric protocol and the presurgical psychiatric interview for morbid obesity between 1 January 2019 and 30 June 2021.

- -

Patients with incomplete data.

The patients included in the study were divided into two comparison groups: those considered unsuitable for any psychopathological cause in the psychiatrist's assessment consultation, and those considered suitable in the consultation.

ROC curve-based methodology was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the tests employed, in which the actual positive state was established to exclude patients at the first consultation for psychological reasons and the actual negative state as the non-exclusion of patients at the first consultation due to psychological causes. The purpose of this statistical analysis was to obtain the sensitivity and specificity values for each of the tests used to exclude patient for any psychological reason.

A descriptive analysis was conducted of the different diagnoses found as the reason for patient exclusion, and a comparison of the sociodemographic and psychometric variables among those excluded and not excluded was also performed.

ResultsIn our study, 100 patients were sent for assessment according to the bariatric surgery protocol during the study period. Three of them completed the psychological interview, but in the end they did not attend the psychiatric interview, so the total number of patients included in the study was 97 patients. The study group consisted of 34 men (35.1%) and 63 women (64.9%), aged between 20 and 61 years, with a mean age of 44.54 (9.48) years. Table 1 lists the sociodemographic variables, the most common being having an unskilled job, i.e. one that does not require a specific qualification to perform it (n = 37; 38.1%), and a basic level of education (n = 42; 43.3%). In 50 cases (51.5%), there was a family history of some psychiatric disorder, and in 37 (38.1%) a personal history of some psychiatric disorder.

Sociodemographic variables.

| Total patients (n = 97) | Suitable (n = 58) | Unsuitable (n = 39) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.54 (9.48) | 45.12 (9.03) | 43.67 (10.16) | 0.462 |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 34 (35.05%) | 21 (36.21%) | 13 (33.33%) | 0.771 |

| Women | 63 (64.95%) | 37 (63.79%) | 26 (66.67%) | |

| Occupational status | ||||

| Skilled job | 20 (20.62%) | 16 (27.59%) | 4 (10.26%) | 0.004 |

| Unemployed | 29 (29.90%) | 10 (17.24%) | 19 (48.72%) | |

| Retired | 11 (11.34%) | 9 (15.52%) | 2 (5.13%) | |

| Unskilled job | 37 (38.14%) | 23 (39.66%) | 14 (35.90%) | |

| Education level | ||||

| Baccalaureate | 14 (14.43%) | 10 (17.24%) | 4 (10.26%) | 0.316 |

| Basic | 42 (43.30%) | 27 (46.55%) | 15 (38.46%) | |

| Vocational training | 32 (32.99%) | 15 (15.46%) | 17 (43.59%) | |

| University | 9 (9.28%) | 6 (10.34%) | 3 (7.69%) | |

| Family psychiatric history | ||||

| Present | 50 (51.55%) | 27 (46.55%) | 23 (58.97%) | 0.230 |

| Absent | 47 (48.45%) | 31 (53.45%) | 16 (41.03%) | |

| Previous psychiatric history | ||||

| Present | 37 (38.14%) | 16 (27.59%) | 21 (53.85%) | 0.009 |

| Absent | 60 (61.86%) | 42 (72.41%) | 18 (46.15%) | |

Of all the patients evaluated, 39 patients (40.2%) were considered unsuitable for psychological reasons after the psychiatric interview. Regarding diagnoses given as the cause of exclusion for bariatric surgery, the distribution was as follows: food addiction — 8 (20.5%); generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) — 6 (15.5%); bulimia nervosa — 10 (25.7%); unspecified eating disorder (UED) — 10 (25.7%); adaptive disorders — 3 (7.7%); alcoholism — 1 (2.6%), and borderline personality disorder (BPD) — 1 (2.6%).

No statistically significant differences were observed between suitable and unsuitable patients for age (p = 0.462), gender (p = 0.771), the existence of family psychiatric history (p = 0.230) or education level (p = 0.316). Significant differences were observed regarding the existence of a personal psychiatric history (p = 0.009) and employment status (p = 0.004). Table 1 gives a breakdown of the sociodemographic variables.

Regarding the psychometric test battery used, Fig. 1 shows the ROC curves for each of the parameters studied and Table 2 shows the scores obtained. We observed statistically significant differences between suitable and unsuitable patients in the following parameters: YFAS scale total score (p < 0.001), YFAS scale severity score (p < 0.001), Salamanca personality scale paranoid trait score (p = 0.004), Salamanca personality scale impulsive trait score (p = 0.006), Salamanca personality scale borderline trait score (p = 0.036), Salamanca personality scale paranoid trait score (p = 0.044), schizotypal trait score of the Salamanca Personality Scale (p = 0.021), total score of the Plutchik Impulsivity Scale (p = 0.001), total score of the Edinburgh Bulimia Scale (p < 0.001), severity score of the Edinburgh Bulimia Scale (p = 0.044), HADS anxiety scale total score (p = 0.002) and HADS depression scale total score (p < 0.001).

ROC curves of the scales used.

YFAS total: total score of the YFAS scale; YFAS severity: severity score of the YFAS scale; EQ-VAS: overall quality of life score of the EuroQoL Visual Analogue Scale; SPTQ-P: paranoid trait of the Salamanca personality traits questionnaire; SPTQ-S: schizoid trait of the Salamanca personality traits questionnaire; SPTQ-ST: schizotypal trait of the Salamanca personality traits questionnaire; SPTQ-H: histrionic trait of Salamanca personality traits questionnaire; SPTQ-AS: antisocial trait of the Salamanca personality traits questionnaire; SPTQ-N: narcissistic trait of the Salamanca personality traits questionnaire; SPTQ-I: impulsive trait of the Salamanca personality traits questionnaire; SPTQ-B: borderline trait of the Salamanca personality traits questionnaire; SPTQ-AN: anankastic trait of the Salamanca personality traits questionnaire; SPTQ-D: dependent trait of the Salamanca personality traits questionnaire; SPTQ-A: anxiety trait of the Salamanca personality traits questionnaire; Total PIS: total score of Plutchik's impulsivity scale; BITE-SYM: total symptoms score of the BITE scale; BITE-SEV: total severity score of the BITE scale; HADS-A: anxiety score of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HADS-D: depression score of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Psychometric test battery results.

| Total patients (n = 97) | Suitable (n = 58) | Unsuitable (n = 39) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) | ||||

| Total score | 2.28 (2.53) | 1.26 (1.55) | 3.79 (2.94) | <0.001 |

| Severity | 0.53 (1.00) | 0.10 (0.36) | 1.15 (1.29) | <0.001 |

| Salamanca Personality Traits Questionnaire (SPTQ) | ||||

| Paranoid | 1.47 (1.39) | 1.24 (1.44) | 1.82 (1.25) | 0.044 |

| Schizoid | 1.65 (1.71) | 1.45 (1.73) | 1.95 (1.65) | 0.158 |

| Schizotypal | 0.52 (0.89) | 0.34 (0.69) | 0.77 (1.09) | 0.021 |

| Histrionic | 2.07 (1.40) | 1.97 (1.48) | 2.23 (1.29) | 0.363 |

| Antisocial | 0.10 (0.45) | 0.07 (0.32) | 0.15 (0.59) | 0.359 |

| Narcissistic | 0.46 (0.93) | 0.55 (1.05) | 0.33 (0.70) | 0.256 |

| Impulsive | 1.56 (1.08) | 1.31 (0.88) | 1.92 (1.24) | 0.006 |

| Borderline | 1.03 (1.27) | 0.81 (1.15) | 1.36 (1.39) | 0.036 |

| Anankastic | 1.78 (1.39) | 1.93 (1.39) | 1.56 (1.38) | 0.203 |

| Dependent | 1.56 (1.44) | 1.66 (1.49) | 1.41 (1.37) | 0.415 |

| Anxious | 2.02 (1.59) | 1.84 (1.51) | 2.28 (1.70) | 0.187 |

| Plutchik's Impulsivity Scale (PIS) | ||||

| Total | 12.74 (4.65) | 11.50 (4.41) | 14.59 (4.44) | 0.001 |

| Bulimic Investigatory Test, Edinburgh (BITE) | ||||

| Symptoms | 9.14 (5.56) | 7.31 (4.90) | 11.87 (5.42) | <0.001 |

| Severity | 1.74 (2.57) | 1.33 (2.72) | 2.36 (2.23) | 0.044 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | ||||

| HADS-A | 7.54 (3.90) | 6.56 (3.07) | 8.97 (4.53) | 0.002 |

| HADS-D | 5.32 (3.45) | 4.04 (2.75) | 7.21 (3.54) | <0.001 |

With regard to the area under the curve, the scales that presented a value greater than 0.7 were the YFAS total score (0.771), the HADS depression scale (0.757), the BITE total score (0.747), the YFAS severity score (0.722) and the BITE severity score (0.705). Table 3 lists the coordinates of the aforementioned scales used and attempts to determine the cut-off point with the greatest sensitivity and specificity. We found that for the YFAS total score this point corresponds to a value >3.5 (sensitivity 0.54; specificity 0.90), for the HADS depression scale it is >4.5 (sensitivity 0.74; specificity 0.65), for the BITE total score it is >9.5 (sensitivity 0.69; specificity 0.72); for the YFAS total severity score it is >1.5 (sensitivity 0.44; specificity 0.98), and for the BITE severity score it is >0.5 (sensitivity 0.77; specificity 0.61).

Coordinates of the scales with area under the curve greater than 0.7.

| Scale | Positive if it is greater than or equal to | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity + Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YFAS total | 1.5 | 0.692 | 0.719 | 1.411 |

| 2.5 | 0.59 | 0.825 | 1.415 | |

| 3.5 | 0.538 | 0.895 | 1.433 | |

| 4.5 | 0.41 | 0.947 | 1.357 | |

| 5.5 | 0.256 | 0.982 | 1.238 | |

| HADS-D | 2.5 | 0.949 | 0.316 | 1.265 |

| 3.5 | 0.821 | 0.474 | 1.295 | |

| 4.5 | 0.744 | 0.649 | 1.393 | |

| 5.5 | 0.615 | 0.754 | 1.369 | |

| 6.5 | 0.564 | 0.807 | 1.371 | |

| BITE symptoms | 7.5 | 0.718 | 0.526 | 1.244 |

| 8.5 | 0.692 | 0.649 | 1.341 | |

| 9.5 | 0.692 | 0.719 | 1.411 | |

| 10.5 | 0.59 | 0.754 | 1.344 | |

| 11.5 | 0.538 | 0.842 | 1.38 | |

| YFAS severity | 0.5 | 0.487 | 0.93 | 1.417 |

| 1.5 | 0.436 | 0.982 | 1.418 | |

| 2.5 | 0.231 | 1 | 1.231 | |

| BITE severity | −1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0.5 | 0.769 | 0.614 | 1.383 | |

| 1.5 | 0.615 | 0.754 | 1.369 |

Regarding the psychometric tools used, we found that the one with the greatest discriminative capacity to differentiate between suitable and unsuitable patients in the first consultation is the YFAS, the design of which is based on the hypothesis of food as an addictive substance. We found that the highest diagnostic performance of this scale is with four or more points on the symptom scale and with two or more points on the severity scale. In both cases, this high diagnostic yield is obtained from a high specificity, so it is not considered to be a good screening tool as it is not very sensitive, although if a positive result is obtained, it is likely that there are symptoms that need to be addressed before continuing with the procedure.

The BITE scale presents more balanced sensitivity and specificity values. The maximum performance score of the symptoms scale corresponds to that obtained by the Spanish validation of the scale that points towards abnormal eating patterns. The severity scale, however, presents its highest diagnostic yield above one, which is much lower than that indicated in the validation (five or more). In our view, this disparity is likely to be influenced by the composition of the sample, which does not compare patients with bulimia with healthy patients, but mixes all types of patients with morbid obesity.

Another striking finding is obtained in the results of the HADS-D scale, which presents a higher diagnostic performance than the HADS-A scale (although the latter is also discriminative), and its highest performance point (five or more) is below that indicated in the Spanish validation (seven or more). This could be attributed to the fact that coping with stressful circumstances through eating could have an antidepressant component and somehow "cover up" a mood alteration for a while, in such a way that the clinical picture of morbid obesity would appear before the c function on the intake mood was exhausted.

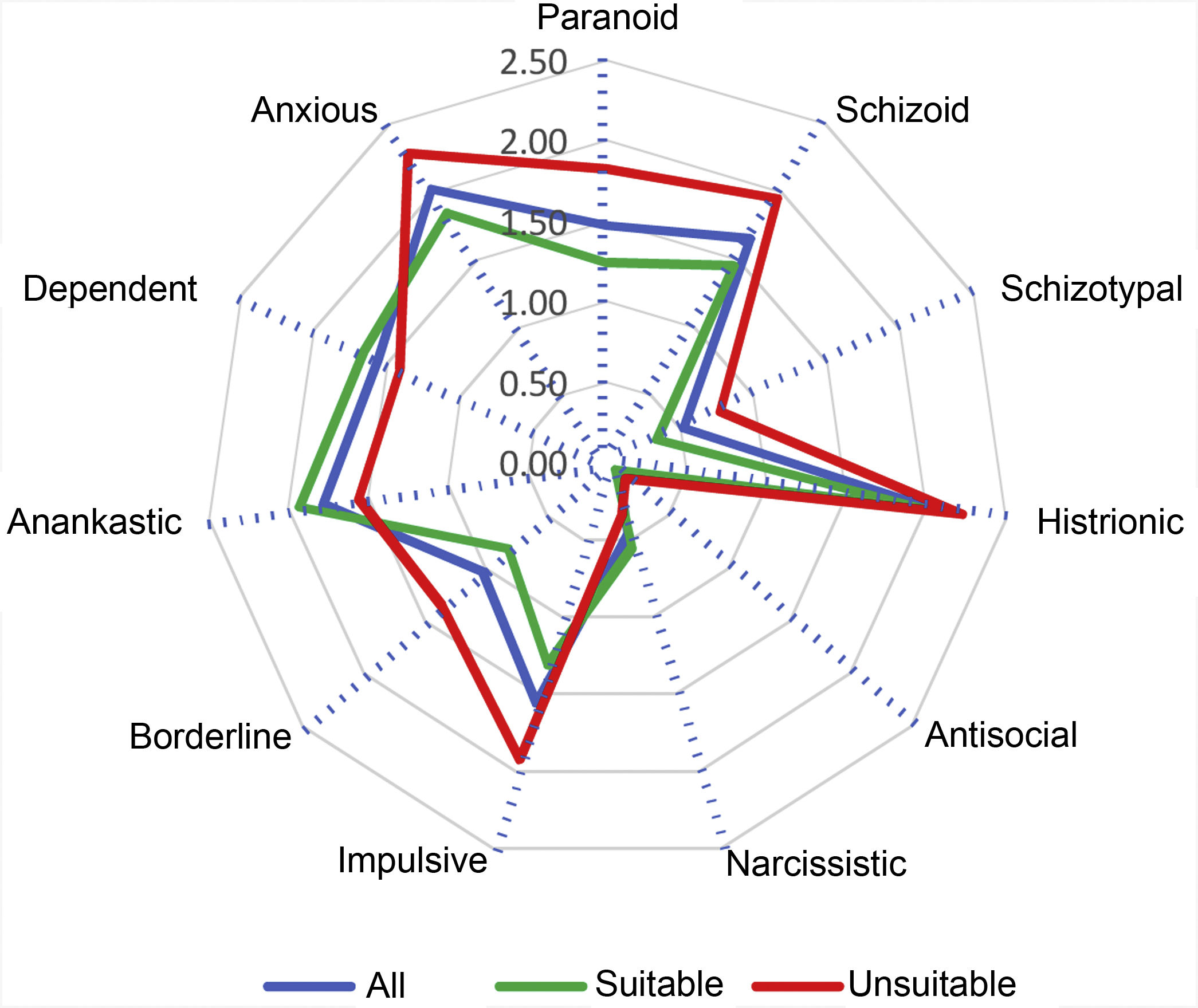

With regard to the other scales used that complete the protocol, we found that Plutchik's impulsivity scale has discriminative capacity, although both in the group of suitable patients and in the unsuitable group, it presented mean scores well below the cut-off point proposed in the Spanish validation (>20). Once again, we attribute this disparity to the heterogeneity of our study group. The most prominent personality traits in our patients are 'histrionic' and 'anxious' (Fig. 2). However, there is no evidence of the discriminative capacity of these traits to differentiate between suitable and unsuitable patients, with schizotypal, borderline, paranoid and impulsive traits being the ones that are more marked in the group of unsuitable patients, which coincides with the literature on the subject.12

We found that the patient profile of those assessed in the bariatric surgery protocol corresponds to a woman around 45 years of age who has a basic level of education and an unskilled job, with a family psychiatric history but no personal psychiatric history. In our opinion, this profile corresponds to a medium-low socioeconomic level and we understand that it may be due to two main causes. On the one hand, the predominance of obesity in social classes with fewer economic resources, with less awareness of and access to healthy food and, on the other hand, the public nature of our hospital, which implies a slower speed in performing surgery and a greater number of administrative steps, which usually does not occur at private hospitals where performing procedures quickly is their main way to compete with a system that is much better equipped, as is the Spanish public health system.

In all, 40.2% of the patients assessed were considered unsuitable after the first psychiatric consultation. This percentage is much higher than in other published studies, where it ranges from 15% to 20%.12,13 We believe that this variation is mainly due to the existence of an integrated multidisciplinary team, which makes it possible to offer different therapeutic alternatives to systematic examination of addictive behaviours, and to the objective of ensuring that the patient is in the best possible psychological situation to face the procedure, which may result in several consultations before the patient is considered suitable.

This in no way means a withdrawal from the procedure, but it is considered that the patient's mental condition is not suitable at the time of assessment to deal with a procedure such as bariatric surgery.

Among the diagnoses found, the main groups correspond to alterations in the anxiety control system, which are accompanied by dysfunctional coping through the use of food as an anxiolytic and contribute to weight gain, bulimic-type eating disorders that are generally not accompanied by purgative behaviours, binge eating disorders, and a last group in which eating food has been considered to be addictive behaviour. The approach to the different diagnoses is different from both the point of view of interaction with the patient and from its psychopharmacological approach. In this way, in anxiety-related conditions, it is hypothesised that the main dysfunction is in the amygdala, and they are usually addressed using drugs from the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) family, mainly fluoxetine, and an interview aimed at identifying anxiety factors and searching for alternative eating behaviours; conditions related to bulimia/binge eating are considered to be an alteration in the regulation of impulsivity, neuroanatomically focusing on the alteration of the interaction between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, while the interview is usually oriented towards the creation of an adequate insight and the reinforcement of external and internal control factors, and psychopharmacologically they are usually treated with a combination of topiramate and fluoxetine; and the last group, which is related to the brain mechanisms of addiction and focuses on the hedonic role of food, is anatomically located in the mesolimbic reward circuits and is usually addressed using the same techniques as other addictions, and is psychopharmacologically directed towards dopaminergic regulation with drugs that can replace this hedronic component, such as bupropion. The other diagnostic groups are marginal in our study and, in the case of depressive disorders, they can usually continue with the procedure once the condition has subsided.

One of the important issues for generalising the results is the lack of consensus on relevant psychiatric conditions in the screening of patients who are candidates for bariatric surgery, as well as on what should be absolute or relative contraindications for it. In this study we applied the clinical protocol developed at our hospital, which could make it difficult to extrapolate to other clinical settings. Another issue to take into account is the instability of psychiatric diagnoses, mainly in the field of neuroses, since what today manifests as a bulimic-type eating disorder may manifest in the future as an addictive condition, generalised anxiety or even a conversion disorder.

With regard to the study's strengths, it was conducted under real clinical conditions in a public hospital. The assessment of patients was comprehensive, with a multidisciplinary and biopsychosocial approach of obesity. As for its limitations, the study was conducted during a single year, in a single centre and is retrospective. Psychiatric history was recorded as a dichotomous variable, without specifying differences. The main variable was exclusion or not for psychological reasons, which could give rise to a greater sensitivity and specificity of each test, depending on the specific psychiatric diagnosis.

ConclusionsToday, obesity in itself is not considered a mental disorder. However, the presence of psychiatric comorbidity is common and in 40.2% of cases it requires intervention prior to surgery.

The scale with the greatest discriminative capacity to differentiate between suitable and unsuitable patients in the first consultation is the YFAS scale. This high diagnostic yield is obtained from high specificity.

Among the diagnoses found, the main groups correspond to alterations in the anxiety control system, which are accompanied by dysfunctional coping through the use of food as an anxiolytic and contribute to weight gain.

The most prominent personality traits in our patients are 'histrionic' and 'anxious'. However, there is no evidence of a discriminative capacity of these traits to differentiate between suitable and unsuitable patients, with schizotypal, borderline, paranoid and impulsive traits being the most marked in the group of unsuitable patients.

The patient profile of those assessed in the bariatric surgery protocol corresponds to a woman around 45 years of age who has a basic level of education and an unskilled job, with a family psychiatric history but no personal psychiatric history.

FundingThis study did not receive any type of funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.