The traditional Mediterranean diet (MD) is associated to a lower risk of suffering multiple tumors. However, few studies have analyzed the relationship between MD and the risk of developing head and neck cancer (HNC). A case-control study comparing adherence to MD was conducted in patients diagnosed with HNC and healthy population.

Patients and methodsThe level of adherence to MD was assessed using the 14-item MEDAS (Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener) questionnaire, used in the PREDIMED study, in patients diagnosed with HNC at 12 de Octubre Hospital in Madrid (cases) and in healthy subjects enrolled in a nearby primary health care center (controls). Adherence was stratified based on the score as low (≤7 points), medium (8–9 points), and high (≥10 points). The odds ratio (OR) for developing HNC was estimated based on different factors.

ResultsA sample of 168 subjects (100 controls and 68 cases) was analyzed. Smoking (OR, 2.98 [95% CI: 1.44–6.12]; p=0.003) and alcohol consumption (OR, 2.72 [95% CI: 1.39–5.33], p=0.003) were strongly associated to HNC. However, medium-high adherence to MD was associated to a lower risk of developing HNC (OR, 0.48 [95% CI: 0.20–1.07], p=0.052).

ConclusionsConsistent medium-high adherence to MD contributes to decrease the risk of developing HNC.

La dieta mediterránea (DM) tradicional se asocia a un menor riesgo de padecer numerosos cánceres. Sin embargo, pocos estudios han analizado la relación de la DM con el riesgo de padecer cáncer de cabeza y cuello (CCyC). Se lleva a cabo un estudio de casos y controles en el que se compara la adherencia a la DM en pacientes diagnosticados de CCyC y población sana.

Pacientes y métodoMediante el cuestionario Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS), de 14 ítems, empleado en el estudio PREDIMED, se evalúa el nivel de adherencia a la DM tanto en casos obtenidos de pacientes diagnosticados de CCyC en el hospital 12 de Octubre de Madrid, como en controles obtenidos de población sana de un centro de salud del Área, estratificando dicha adherencia en función de la puntuación: baja (≤7 puntos), media (8-9 puntos) y alta (≥10 puntos). Se calcula el odds ratio (OR) para desarrollar CCyC en base a diferentes factores.

ResultadosSe analiza una muestra de 168 individuos: 100 controles y 68 casos. El hábito tabáquico (OR: 2,98 [IC 95%: 1,44-6,12]; p=0,003) y el consumo de alcohol (OR: 2,72 [IC 95%: 1,39-5,33]; p=0,003) demuestran ser factores de riesgo para desarrollar CCyC. Sin embargo, la adherencia media-alta a la DM se asocia a menor riesgo de CCyC (OR: 0,48 [IC 95%: 0,20-1,07]; p=0,052).

ConclusionesLa adherencia media-alta a la DM se asocia a menor riesgo para desarrollar CCyC.

Cancer is the second leading cause of mortality in the world. It accounted for 8.8 million deaths in 2015,1 and 1.3 million deaths in Europe in 2014, representing 26.4% of all fatalities.2 In 2015, approximately 250,000 new cases of invasive malignancy were diagnosed in Spain, 60% in men and 40% in women.3

Between 5 and 10% of all cancers can be attributed to genetic alterations, while the remaining 90–95% are derived from environmental and lifestyle factors.4 Smoking, alcohol abuse, an unhealthy diet and low physical activity are the main risk factors for developing cancer. Approximately 40% of all cancers could be prevented by eliminating risk factors and implementing preventive strategies.1 Smoking alone is the leading cause, accounting for 33% of all cancer cases.5

Diet is a modifiable risk factor in the origin of cancer, because adequate nutrition has been reported to play a key role in reducing the incidence of some tumors.6 The traditional Mediterranean diet (MD) has been associated with a lower overall risk of cardiovascular and oncological disease.4,7 In relation to head and neck cancer (HNC), the existing evidence is based on only four studies: a cohort trial and three case-control studies.8–11 However, only one of the case-control studies exclusively analyzed the risk regarding HNC,9 since the other studies also included tumors of the upper aerodigestive tract.

In view of the scant evidence in the literature on this subject, a case-control study was designed with the primary objective of comparing adherence to the MD in patients diagnosed with HNC versus the healthy population, using the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS) questionnaire. Based on 14 items, this questionnaire analyzes the consumption of the main components of the MD and their recommended amounts. The MEDAS questionnaire was used in the PREDIMED (Prevention with Mediterranean Diet) study,12 which was itself based on the Mediterranean Dietary Score proposed by Trichopoulou et al.13,14 As secondary objectives, the present study explores whether there are any specific aspects of the MD that differ between the two populations, and moreover evaluates whether the healthy population in our setting follows the MD, and whether adherence to the latter is conditioned by the purchasing power or cultural level of the population.

Material and methodsType of study and population analyzedA case-control study was designed to analyze adherence to the MD in two different groups: (a) patients over 18 years of age diagnosed with HNC in the first 6 months of 2018 (“cases”); and (b) healthy individuals without HNC (“controls”). The sample of cancer patients was obtained from the Department of Radiation Oncology of Hospital Doce de Octubre (Madrid, Spain). The healthy population sample in turn was obtained through the systematic sampling of subjects over 18 years of age visiting General Ricardos primary care center (Madrid, Spain) as accompanying persons.

The sample size was calculated using the GRANMO sample size calculator (version 7.12, April 2012), which adopts the POISSON approach. Assuming an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2 in two-tailed testing, 62 cases and 62 controls were seen to be required in order to detect a minimum odds ratio (OR) of 0.2. We assumed the MD exposure rate in the control group to be 0.9, based on the results published for the healthy Spanish population.15 The estimated loss to follow-up rate was 20%.

Dietary assessmentAll the participants were invited to complete a survey containing the questions included in the MEDAS questionnaire, which was developed as part of the PREDIMED trial12 to allow for a simple and rapid assessment of adherence to the MD. It was chosen because the questionnaires most commonly used in other studies to analyze the amount and frequency of food ingested (semiquantitative food frequency questionnaires [FFQs]) take considerable time to complete. It is considered a valid and effective instrument for assessing adherence to the MD, since its validity and applicability have been compared and confirmed against other questionnaires with a larger number of items.16 The questionnaire includes 14 questions assessing the frequency and consumption habits of different foods considered characteristic of the MD in Spain (anexo 1). For each item, an affirmative response is scored as one point, while a negative response corresponds to zero points. Thus, the score of the MEDAS questionnaire ranges from 0 to 14 points.

Study variablesThe study analyzes sociodemographic variables (age, gender, educational level, income level), knowledge of the MD, smoking and alcohol consumption, the type of HNC among the cases, and the list of 14 items of the MEDAS questionnaire. Alcohol consumption was stratified into two categories (yes/no) according to the intake of two or more alcoholic drinks in men or one or more alcoholic drinks in women per day. In addition, two other variables were studied: one referring to whether the social and family environment of the participants influenced adherence to the MD, and another exploring whether dietary habits were conditioned by family income. The full questionnaire with all the mentioned variables can be found in anexo 2. Since a priori the cultural level of the respondents was not known, the questions in the survey were stated as clearly and simply as possible. We therefore used closed statements with excluding response categories (affirmative/negative). For the general validation of the questionnaire, we conducted a pilot study with a reduced sample of 20 subjects, confirming by interview that they understood correctly each item and answer.

Ethical particulars and data confidentialityData compilation complied with the ethical requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki (revision of Seoul [Korea], October 2008) referring to research with humans, as well as with the applicable regulations on biomedical research (Act 14/2007, of 3 June) and clinical trials with medicinal products (Spanish Royal Decree [RD] 223/2004, of 6 February). Following the applicable legal provisions, the study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Doce de Octubre (Madrid, Spain).

All patients signed the corresponding informed consent document. In compliance with Act 15/1999, of 13 December, on Personal Data Protection (LOPD), the required personal and healthcare data were coded in order to preserve patient confidentiality. All participants were able to use their right to access, change or cancel such data at any time by contacting the investigator (BSA).

Statistical analysisThe null hypothesis assumes that the MD does not represent a protective factor against HNC, due to the absence of differences in the level of adherence to the MD between the cancer patients and healthy controls. However, according to the alternative hypothesis, the MD is a protective factor due to an increased adherence in healthy subjects versus the patients diagnosed with HNC.

The primary endpoint analyzed to verify whether the proposed hypothesis was confirmed was the final MEDAS score, which reflected the level of adherence to MD. Based on the reference intervals of the PREDIMED study,12 a score of ≤7 was considered to indicate poor adherence; a score of 8–9 moderate adherence, and a score of ≥10 good adherence.

Continuous variables were reported as the mean, median and standard deviation, and qualitative variables as absolute and relative frequencies. The chi-squared test and the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test were used to explore concordances between the cases and controls referring to each study measure. We also estimated the odds ratio (OR) of presenting HNC, with its corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI), according to the risk factors considered. A binary and multiple logistic regression model adjusted for the different confounding factors was used for this purpose. A probability of 95% was accepted as significant in all cases.

The statistical analysis was performed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 for MS Windows.

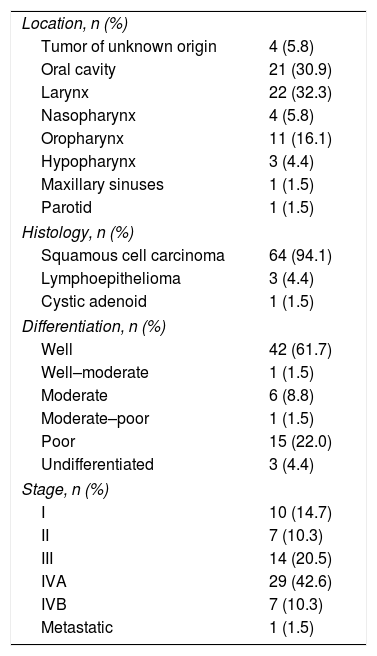

ResultsThe study sample comprised 168 subjects (40.5% females and 59.5% males) with a mean age of 61.8±15.3 years. A total of 25.6% were smokers and 32.1% consumed alcohol. The sample consisted of 68 cases and 100 controls. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients with HNC according to tumor location, histology, the degree of differentiation, and the stage. In addition to the percentages reported in the table, the study included a case of laryngeal malignancy associated with the hypopharynx (1.5% of the global cases studied).

Characteristics of the neoplasms in the case group (n=68).

| Location, n (%) | |

| Tumor of unknown origin | 4 (5.8) |

| Oral cavity | 21 (30.9) |

| Larynx | 22 (32.3) |

| Nasopharynx | 4 (5.8) |

| Oropharynx | 11 (16.1) |

| Hypopharynx | 3 (4.4) |

| Maxillary sinuses | 1 (1.5) |

| Parotid | 1 (1.5) |

| Histology, n (%) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 64 (94.1) |

| Lymphoepithelioma | 3 (4.4) |

| Cystic adenoid | 1 (1.5) |

| Differentiation, n (%) | |

| Well | 42 (61.7) |

| Well–moderate | 1 (1.5) |

| Moderate | 6 (8.8) |

| Moderate–poor | 1 (1.5) |

| Poor | 15 (22.0) |

| Undifferentiated | 3 (4.4) |

| Stage, n (%) | |

| I | 10 (14.7) |

| II | 7 (10.3) |

| III | 14 (20.5) |

| IVA | 29 (42.6) |

| IVB | 7 (10.3) |

| Metastatic | 1 (1.5) |

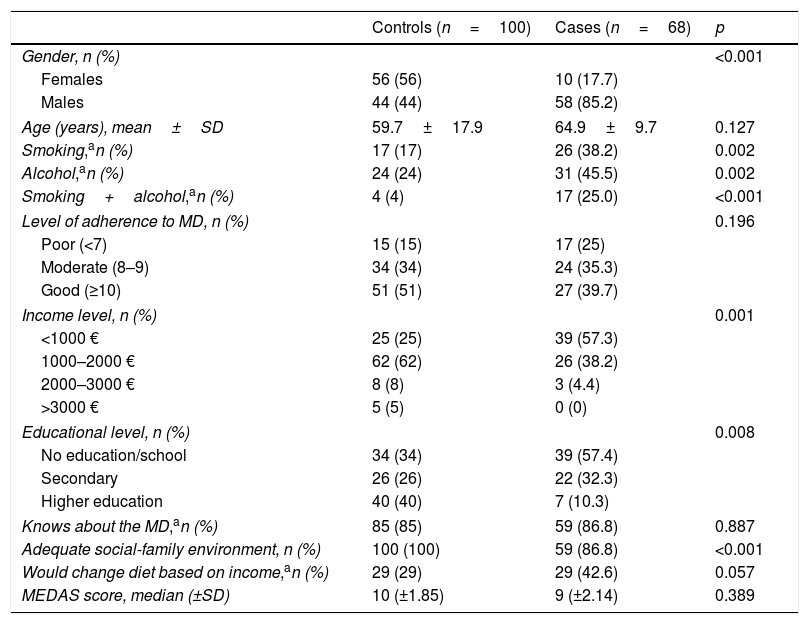

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the study population. As noted in the table, in the group corresponding to the cases there was a greater representation of males, as well as a higher percentage of smokers and drinkers. The cases also had a lower monthly income and were less likely to have an adequate family environment. The mean MEDAS score among the controls was 9.30±1.85 points (median 10), very similar to that recorded among the cases: 9.01±2.14points (median 9). However, 85% of the controls showed moderate–good adherence to the MD (≥8 points), versus 75% of the cases. In the multivariate analysis, gender (p=0.000), alcohol intake (p=0.001), moderate–good adherence to the MD (p=0.027), basic educational level (p=0.002) and a monthly income of less than 1000euros/month (p=0.012) were identified as independent risk factors for developing HNC.

Characteristics of the study population.

| Controls (n=100) | Cases (n=68) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Females | 56 (56) | 10 (17.7) | |

| Males | 44 (44) | 58 (85.2) | |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 59.7±17.9 | 64.9±9.7 | 0.127 |

| Smoking,an (%) | 17 (17) | 26 (38.2) | 0.002 |

| Alcohol,an (%) | 24 (24) | 31 (45.5) | 0.002 |

| Smoking+alcohol,an (%) | 4 (4) | 17 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| Level of adherence to MD, n (%) | 0.196 | ||

| Poor (<7) | 15 (15) | 17 (25) | |

| Moderate (8–9) | 34 (34) | 24 (35.3) | |

| Good (≥10) | 51 (51) | 27 (39.7) | |

| Income level, n (%) | 0.001 | ||

| <1000 € | 25 (25) | 39 (57.3) | |

| 1000–2000 € | 62 (62) | 26 (38.2) | |

| 2000–3000 € | 8 (8) | 3 (4.4) | |

| >3000 € | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Educational level, n (%) | 0.008 | ||

| No education/school | 34 (34) | 39 (57.4) | |

| Secondary | 26 (26) | 22 (32.3) | |

| Higher education | 40 (40) | 7 (10.3) | |

| Knows about the MD,an (%) | 85 (85) | 59 (86.8) | 0.887 |

| Adequate social-family environment, n (%) | 100 (100) | 59 (86.8) | <0.001 |

| Would change diet based on income,an (%) | 29 (29) | 29 (42.6) | 0.057 |

| MEDAS score, median (±SD) | 10 (±1.85) | 9 (±2.14) | 0.389 |

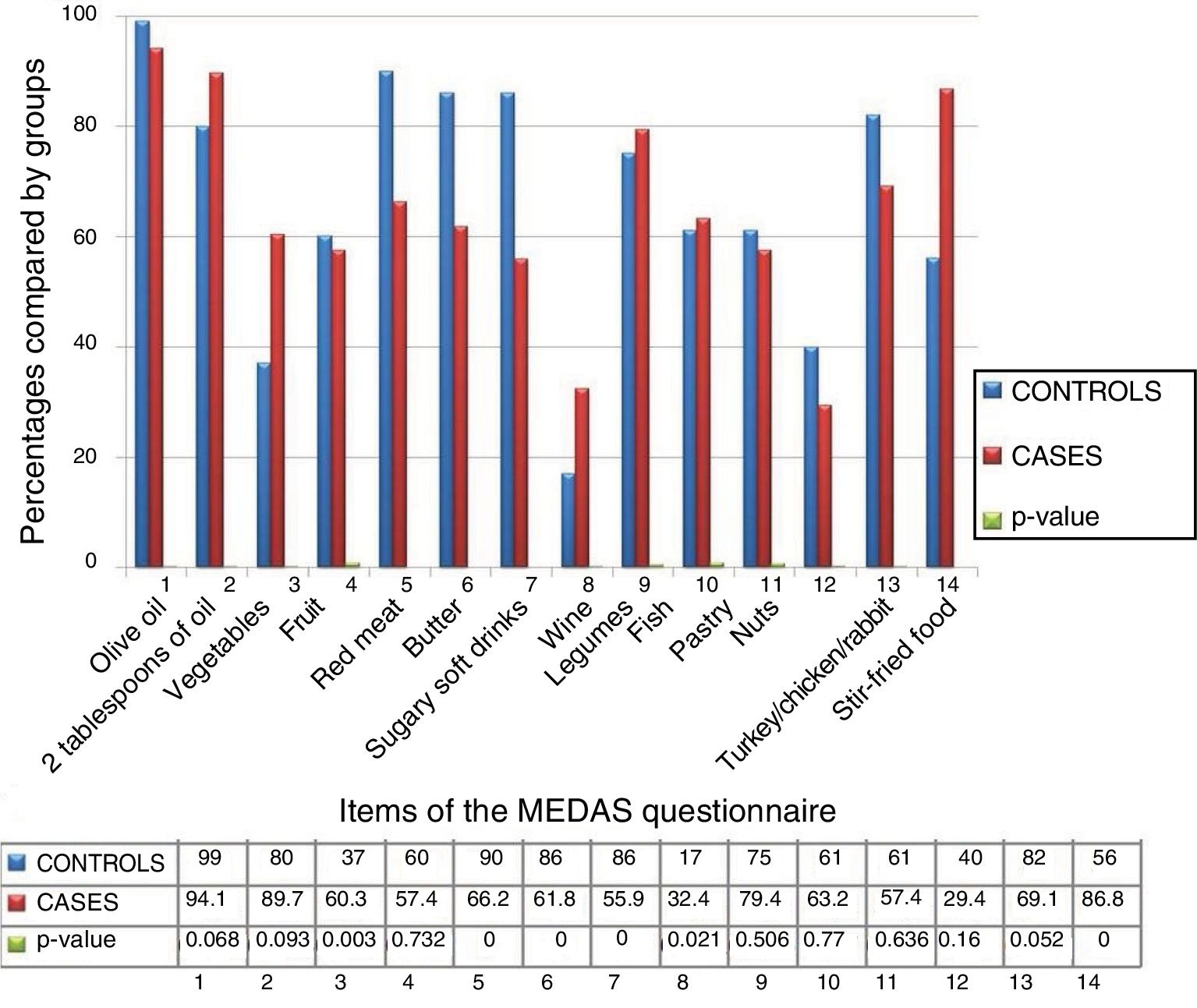

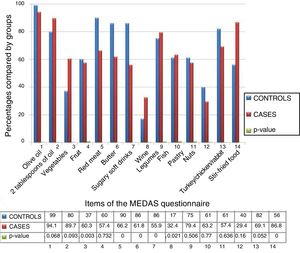

Fig. 1 shows the differences according to groups for each of the 14 items included in the MEDAS questionnaire. The cases consumed more wine than the controls, who in turn consumed more vegetables (p<0.005). On excluding item number 8 of the MEDAS questionnaire (“7 or more glasses of wine a week”) from the analysis, the absolute value of the difference between the cases and controls was seen to increase (8.73±2.19 versus 9.01±1.63), but the difference was not statistically significant.

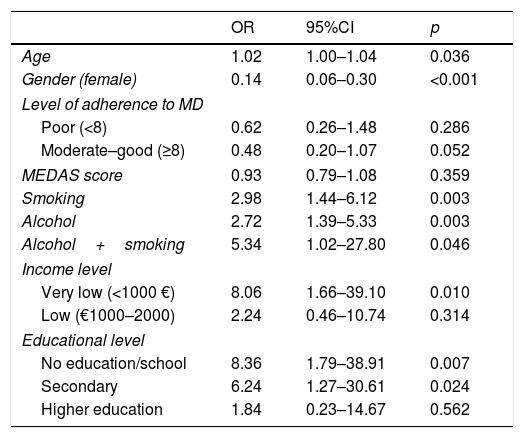

Table 3 shows the OR of suffering HNC adjusted for each variable. Age, gender, smoking, alcohol abuse, an average income of less than 1000euros/month, and a basic educational level were identified as risk factors for HNC. Moderate–good adherence to the MD was seen to be a protective factor (p=0.05). However, the absolute score of the MEDAS questionnaire was unable to discriminate adherence to the MD between the cases and controls, it being at a similarly high level in the two groups (p=0.359).

Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95%CI) for head and neck cancer adjusted for all variables.

| OR | 95%CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | 0.036 |

| Gender (female) | 0.14 | 0.06–0.30 | <0.001 |

| Level of adherence to MD | |||

| Poor (<8) | 0.62 | 0.26–1.48 | 0.286 |

| Moderate–good (≥8) | 0.48 | 0.20–1.07 | 0.052 |

| MEDAS score | 0.93 | 0.79–1.08 | 0.359 |

| Smoking | 2.98 | 1.44–6.12 | 0.003 |

| Alcohol | 2.72 | 1.39–5.33 | 0.003 |

| Alcohol+smoking | 5.34 | 1.02–27.80 | 0.046 |

| Income level | |||

| Very low (<1000 €) | 8.06 | 1.66–39.10 | 0.010 |

| Low (€1000–2000) | 2.24 | 0.46–10.74 | 0.314 |

| Educational level | |||

| No education/school | 8.36 | 1.79–38.91 | 0.007 |

| Secondary | 6.24 | 1.27–30.61 | 0.024 |

| Higher education | 1.84 | 0.23–14.67 | 0.562 |

Head and neck cancer (HNC) comprises a group of neoplasms located in the paranasal sinuses, nasopharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, oral cavity, tongue and salivary glands. The definition of HNC excludes neck skin cancer, brain malignancies and thyroid tumors. Tumors located in the head or neck are predominantly found in males; in the case of Spain, the male predominance over females is 10:1. The worldwide incidence and mortality of these tumors is 5%, according to data from GLOBOCAN.17 Between 12,000 and 14,000 new cases are diagnosed every year in Spain. The estimated survival rate is 75% at one year and 42% at 5 years. The seriousness of HNC is explained by the fact that two out of every three cases are detected in advanced stages of the disease, since the symptoms usually go unnoticed in the early stages, thereby causing a delay in diagnosis.18

Different studies have established a high level of evidence on the role of smoking,19,20 alcohol abuse8,21 and human papillomavirus infection22 as leading risk factors for the development of HNC. The data obtained in our study agree with the results found in the literature and the available evidence in this regard. Seventy-five percent of all HNC are attributable to these factors,18 and the risk increases in individuals who smoke and drink.23 Age has also been reported as a risk factor, since the mean patient age at onset of HNC is over 50 years; furthermore, as commented above, these tumors are predominantly found in males. In our series there were significant differences between the cases and controls in relation to smoking, alcohol consumption and gender. The OR of developing cancer in relation to smoking was 2.98, which represents an almost three-fold increase in risk. In relation to alcohol abuse the OR was 2.72 (a two-fold increase), while concomitant smoking and alcohol abuse implied a 5-fold increase in cancer risk (OR 5.34). With regard to patient age, the risk was seen to increase by 2% with each additional year (OR 1.02). In the case of gender, female status constituted a protective factor, with an 86% lesser risk compared with males (OR 0.14). In coincidence with the available evidence, the most common location of HNC in our study was the larynx (32.3%), followed by the oral cavity, oropharynx and nasopharynx. The most common histological presentation was squamous cell carcinoma (94.1%), in advanced stages (42.6% in stage IVA).18,23

The traditional MD has the characteristics of the anticancer diet defined by the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) and represents a healthy diet model. These institutions recommend following a diet rich in whole grains, legumes, fruit and vegetables, with a limited consumption of high-calorie, high-salt foods, and the avoidance of sugary beverages and red or processed meats.6 The traditional MD is characterized by a high intake of vegetables, fruits, legumes and cereals (mainly whole grains). Olive oil is the main source of fat, along with a low intake of saturated fats as compared to unsaturated fats; a moderate–high intake of dairy products (mainly cheese and yoghurt) and fish; a moderate intake of alcohol (mainly wine), and a low intake of red meat. The biological mechanisms responsible for the protective role of the MD against cancer include the synergistic combination of nutrients,24–26 affording a balanced proportion of omega-6 essential fatty acids and omega-3 fatty acids, abundant fiber, vitamins C and E, polyphenols, carotenoids and antioxidant ingredients in fruit, vegetables, legumes, nuts, olive oil and wine.7,27 The combination of the different ingredients of the MD affords antioxidant activity, inhibits systemic inflammation processes, and has antiproliferative and antimutagenic properties, exerting an influence upon cell signaling, cell cycle regulation and angiogenesis.28

Three meta-analyses have reviewed the relationship between adherence to the MD and cancer risk, and have shown that a high level of adherence to the MD results in a significant decrease in the risk of mortality and/or the incidence of certain tumors such as colorectal, breast, prostate, stomach, liver and head and neck cancers.24–26 Moderate–good adherence to the MD is a protective factor against the development of HNC, as shown by the results of other published studies and systematic reviews.8–11,29,30 Three case-control studies and a cohort trial have analyzed the impact of the MD on the risk of HNC. According to Bosetti et al.,10 an increased adherence to the MD significantly reduces the risk of malignancies of the oral cavity and pharynx, and laryngeal cancer, by 23% and 29%, respectively. Samoli et al.8 showed adherence to the traditional MD to be associated with a lesser risk of cancer of the oral cavity and oropharynx, larynx, and esophagus encompassed as cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Filomeno et al.9 in turn argued that there is considerable evidence regarding the protective role of the MD in relation to cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx, with a decrease in risk of 27%. The only published cohort study prospectively evaluating the association between the MD and the risk of HNC found a significant risk reduction in subjects with a good adherence to the MD.11 Furthermore, good adherence was not only related to HNC risk reduction, but also to a 60% decrease in mortality risk regarding tumors of this kind.26 Our study analyzed the association between adherence to the MD and the development of HNC based on the MEDAS questionnaire used in the PREDIMED study. The PREDIMED trial was a multicenter study conducted over 5 years in 7447 individuals that analyzed the role of the traditional MD in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease.27 A review of the literature yielded no articles using the MEDAS questionnaire to assess adherence to the MD in patients diagnosed with HNC. In our sample no significant differences were observed in the absolute MEDAS score, which was found to be over 9 points in both the cases and the controls, even after we eliminated the item referring to the intake of “7 or more glasses of wine a week”, since alcohol is a known risk factor for HNC. We did observe differences in the proportion of subjects with moderate–good adherence to the MD, which proved greater among the controls.

Lastly, consideration should be made of the influence of educational level and income upon the risk of HNC. Our study recorded an OR of 8.36 for the lowest educational level and of 8.06 for the lowest average monthly income level (<1000euros/month), this representing an 8-fold increase in cancer risk in these situations. A total of 42.6% of the cases reported that they would modify their diet if their income were improved, as compared to 29% of the controls. The increased risk of tumors of this kind in individuals with a lower educational level or income is consistent with the epidemiological data reported by Gupta et al.31 These authors found two-thirds of all cases of HNC worldwide to be concentrated in developing countries. The great difference in incidence and mortality among countries according to their level of development will persist, since estimates for the year 2030 indicate that the increase in incidence will continue to be greater in less developed countries. These data reveal a public health problem requiring healthcare and political intervention. Attention should focus on modifiable risk factors in order to prevent the development of tumors of this kind, including adherence to the MD.

Study limitationsSince this is a case-control study, we consider it as merely a first step in the investigation of the relationship between adherence to the MD and the development of HNC. A limitation of the study is the fact that the individuals belonging to the case group answered the survey thinking about the diet they had before being diagnosed with HNC. We thus believe there may have been recall bias in the collection of information because of the need to refer to past habits through personal memory.

Moreover, completion of the survey was not supervised by trained staff in all cases. This factor, added to the low educational level of the study population, could have influenced understanding of the questions in the questionnaire. However, in order to control for this bias, we conducted a pilot study with 20 participants, confirming that they understood the items of the survey and that the latter was adequately answered.

In addition, although the MEDAS questionnaire used in this study had been validated and shown to be useful in rapidly and easily determining adherence to the MD, it had not been used before in studies involving patients with HNC, according to the data found in the literature.

ConclusionsBased on the data obtained in our study it may be affirmed that moderate–good adherence to the MD is associated with a lesser risk of HNC. Furthermore, in agreement with the published evidence, alcohol and smoking are the main risk factors for these tumors, with a 2–3 fold increase in risk for each factor separately, and a 5-fold increase in risk when both factors are present simultaneously. Since the MEDAS score was very similar for both the cases and controls, even after the item referring to wine consumption was eliminated, we consider it necessary to continue conducting studies on the relationship between adherence to the MD and the risk of HNC. If our results are confirmed, then adherence to the MD may prove to be a preventive strategy in relation to tumors of this kind.

Financial supportThe present study received no specific funding from public, commercial or non-profit sources.

AuthorshipAdriana Salvatore contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, and to the final approval of the manuscript.

M. Ángeles Valero contributed to the conception and design of the study, participated in data interpretation, drafted the article, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Marina Alarza contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, and to the final approval of the manuscript.

Ana Ruíz-Alonso contributed to the study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, the critical review of the contents, and the final approval of the submitted version.

Irene Alda contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, and to the final approval of the manuscript.

Eloísa Rogero-Blanco contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, and to the final approval of the manuscript.

María Maíz contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, and to the final approval of the manuscript.

Miguel León-Sanz supervised the field work and contributed to data interpretation, and to the final approval of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to the contents of the manuscript.

Thanks are due to Cristina Martín-Arriscado for her invaluable and disinterested help with the statistical analysis of this study.

Please cite this article as: Salvatore Benito A, Valero Zanuy MÁ, Alarza Cano M, Ruiz Alonso A, Alda Bravo I, Rogero Blanco E, et al. Adherencia a la dieta mediterránea: comparación entre pacientes con cáncer de cabeza y cuello y población sana. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:417–424.