To determine the risk of hypothyroidism in pregnant women with autoimmune thyroid disease and thyrotropin (TSH)<2.5mIU/l at the beginning of pregnancy.

MethodsProspective longitudinal study of pregnant women with no personal history of thyroid disease, and with TSH<2.5mIU/l in the first trimester. TSH, free thyroxine (FT4), anti peroxidase (TPO) and anti thyroglobulin antibodies were measured in the 3 trimesters of pregnancy. We compared thyroid function throughout pregnancy, and the development of gestational hypothyroidism (TSH>4mIU/l) among pregnant women with positive thyroid autoimmunity and those with negative autoimmunity.

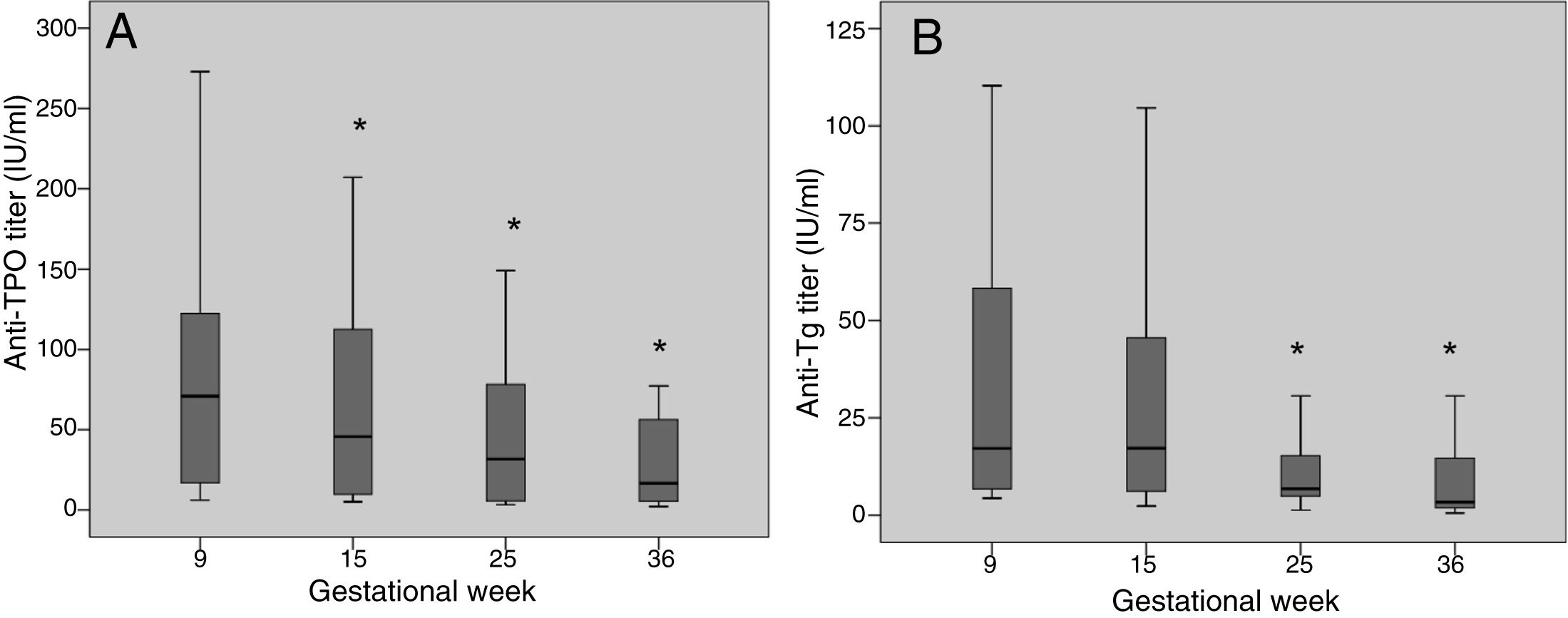

ResultsWe included 300 pregnant women with mean baseline TSH 1.3±0.6mIU/l (9th gestational week). Positive thyroid autoimmunity was detected in 17.7% of women (n=53) at the first trimester. Between the first and the third trimesters, TPO and anti thyroglobulin antibodies titers decreased 76.8% and 80.7% respectively. Thyroid function during pregnancy was similar among the group with positive autoimmunity and the group with negative autoimmunity, and the development of hypothyroidism was 1.9% (1/53) and 2% (5/247) respectively. Pregnant women in whom TSH increased above 4mIU/l (n=6), had higher baseline TSH levels compared to those who maintained TSH≤4mIU/l during pregnancy (1.8 vs. 1.3mIU/l; p=0.047).

ConclusionIn our population, women with TSH levels <2.5mIU/l at the beginning of pregnancy have a minimal risk of developing gestational hypothyroidism regardless of thyroid autoimmunity.

Determinar el riesgo de hipotiroidismo en gestantes con enfermedad tiroidea autoinmune y tirotropina (TSH) < 2,5 mUI/l al inicio del embarazo.

MétodosEstudio prospectivo longitudinal en gestantes de primer trimestre sin antecedentes de patología tiroidea y con TSH en primer trimestre < 2,5 mUI/l. Se determinaron TSH, tiroxina libre (T4l) y anticuerpos antiperoxidasa (TPO) y antitiroglobulina en los 3 trimestres. Se comparó la evolución de la función tiroidea y la aparición de hipotiroidismo gestacional (TSH > 4 mUI/l), entre las gestantes con autoinmunidad positiva y autoinmunidad negativa.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 300 gestantes con TSH basal 1,3±0,6 mUI/l (semana gestacional 9). El 17,7% (n = 53) tenían autoinmunidad positiva en el primer trimestre. Los títulos de anticuerpos TPO y antitiroglobulina disminuyeron entre el primer y el tercer trimestre un 76,8% y un 80,7% respectivamente. La evolución de la función tiroidea fue similar en el grupo con autoinmunidad positiva y el grupo con autoinmunidad negativa, y la aparición de hipotiroidismo fue del 1,9% (1/53) y del 2% (5/247) respectivamente. Las gestantes en las que la TSH aumentó por encima de 4 mUI/l (n = 6) tenían cifras superiores de TSH basal en comparación con las que mantuvieron TSH≤4 mUI/l a lo largo del embarazo (1,8 vs. 1,3 mUI/l; p = 0,047).

ConclusiónEn nuestra población, las mujeres con TSH < 2,5 mUI/l al inicio del embarazo tienen un riesgo mínimo de desarrollar hipotiroidismo durante la gestación, independientemente de la autoinmunidad tiroidea.

The reported prevalence of thyroid autoimmune disorders in pregnant women ranges from 3% to 18%,1 and these disorders are associated with an increased risk of maternal and fetal complications, mainly miscarriage and preterm delivery.2–4 In addition, women with positive thyroid autoimmunity usually have higher thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels at the start of pregnancy as compared to those without such autoimmunity.5,6 The presence of anti-thyroperoxidase (TPO) and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies (anti-Tg) in pregnant women has been related to different factors such as a family history of autoimmune thyroid disease, age, parity and iodine deficiency or excess.7–9

Anti-thyroid antibody titers are higher in the first trimester and then decrease considerably during pregnancy, with eventual negative conversion in some cases.10 Despite this, it is considered that women with positive thyroid autoimmunity are at an increased risk of developing hypothyroidism during pregnancy; monitoring of thyroid function is therefore advised mainly during the first half of pregnancy.11,12

The purpose of this study was to determine the percentage of pregnant women with positive thyroid autoimmunity and TSH<2.5mIU/l in the first trimester who develop hypothyroidism during pregnancy, and to compare them with a control group of pregnant women with negative autoimmunity.

Material and methodsStudy populationA prospective study was made of 400 women in the first trimester of pregnancy with no history of thyroid disease and no drug treatment capable of affecting thyroid function (amiodarone, lithium, levothyroxine, antithyroid drugs). The participants were recruited from two women's health care centers on the occasion of their first prenatal visit, and were assessed in person at the Department of Endocrinology of Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra (Pamplona, Spain) between May 2014 and May 2016. At this visit, a case history was compiled, with physical examination, thyroid ultrasound and the collection of a simple urine sample for measuring ioduria. Determinations were made of TSH, free thyroxine (FT4), and anti-TPO and anti-Tg antibodies, coinciding with the routine laboratory tests made during pregnancy (gestational weeks 9, 15, 25 and 36).

For the present study, we excluded women with multiple pregnancy (n=14), thyroid nodules >1cm in size (n=24) and/or those with TSH in the first trimester ≥2.5mIU/l (n=62). The final study population thus comprised 300 pregnant women. The appearance of hypothyroidism was defined as a TSH elevation above 4mIU/l at any time during pregnancy.

Miscarriages and preterm deliveries (before gestational week 37) occurring during the study were recorded.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Navarre, and all included pregnant women signed the corresponding informed consent form.

Laboratory tests and ultrasound studyBlood samples for the determination of TSH, FT4, and anti-TPO and anti-Tg antibodies were analyzed by the core laboratory of Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra using chemiluminescence (Abbott method). All the samples were collected in the morning. Anti-TPO and anti-Tg positivity was considered in the presence of values above the upper limit of normal. The titers (numerical values) of both antibodies were also recorded.

The determination of ioduria was carried out in the Public Health Standard Laboratory of the Basque Government in Derio (Vizcaya) using ion-pair reversed-phase liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection and a silver electrode (Waters Chromatography, Milford, MA, USA). Detailed information on the procedure and validation of the method and its within- and between-serial precision has been published elsewhere.13 The urine samples were stored in the Biobank, frozen at −20°C, and duly identified, until submission for analysis.

Thyroid ultrasound was performed with the patient in the dorsal decubitus position using a MicroMaxx® portable ultrasound device (Sonosite, Bothell, WA, USA) with a 5–12MHz linear probe. Thyroid volume (in ml) was calculated by summing the volume of both thyroid lobes (volume of each lobe=longitudinal axis [cm]×transverse axis [cm]×anteroposterior axis [cm]×0.479).

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while quantitative variables were expressed as measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation [SD] and interquartile range [IQR]).

Normal distribution of the variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The TSH and FT4 levels according to positive thyroid autoimmune testing were compared using the parametric Student t-test or nonparametric Mann–Whitney test, as applicable. Associations between categorical variables were assessed using the χ2 test. The SPSS version 20 statistical package was used throughout. Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05.

ResultsBaseline population characteristicsThe study comprised 300 pregnant women in the first trimester of pregnancy (95% Caucasians), evaluated in gestational week 10 (range 6–18). Median ioduria was 242μg/l (range 148.5–413), which is consistent with an iodine-sufficient population according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. A total of 98.3% of the women were receiving drug supplementation with potassium iodide at the time of evaluation (mean iodine dose: 202.6±30.1μg daily).

Fifty-three of the pregnant women (17.7%) showed positive autoimmunity in the first trimester. Of these, 15.1% (n=8) had positive anti-TPO antibodies, 47.2% (n=25) had positive anti-Tg antibodies, and 37.7% (n=20) proved positive for both antibodies.

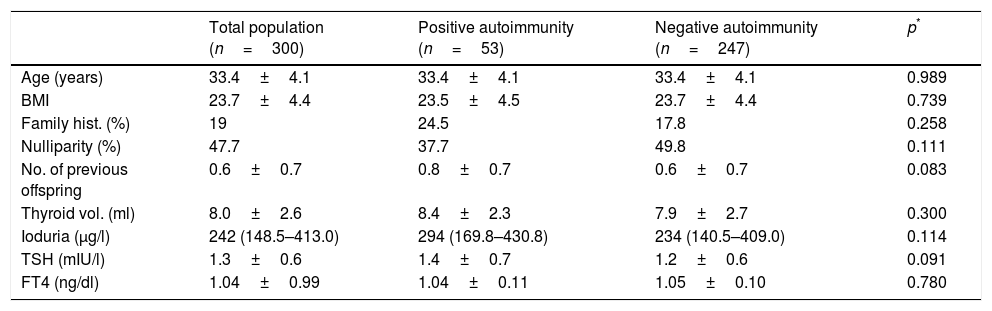

There were no baseline differences between women with positive thyroid autoimmunity and those with negative autoimmunity (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of the study population in the first trimester of pregnancy.

| Total population (n=300) | Positive autoimmunity (n=53) | Negative autoimmunity (n=247) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33.4±4.1 | 33.4±4.1 | 33.4±4.1 | 0.989 |

| BMI | 23.7±4.4 | 23.5±4.5 | 23.7±4.4 | 0.739 |

| Family hist. (%) | 19 | 24.5 | 17.8 | 0.258 |

| Nulliparity (%) | 47.7 | 37.7 | 49.8 | 0.111 |

| No. of previous offspring | 0.6±0.7 | 0.8±0.7 | 0.6±0.7 | 0.083 |

| Thyroid vol. (ml) | 8.0±2.6 | 8.4±2.3 | 7.9±2.7 | 0.300 |

| Ioduria (μg/l) | 242 (148.5–413.0) | 294 (169.8–430.8) | 234 (140.5–409.0) | 0.114 |

| TSH (mIU/l) | 1.3±0.6 | 1.4±0.7 | 1.2±0.6 | 0.091 |

| FT4 (ng/dl) | 1.04±0.99 | 1.04±0.11 | 1.05±0.10 | 0.780 |

Values are reported as mean±standard deviation, except for ioduria, which is expressed as median (P25–P75). TSH (mIU/l) and FT4 (ng/dl) correspond to gestational week 9, and thyroid volume and ioduria to gestational week 10.

Family hist.: family history; thyroid vol.: thyroid volume.

Pregnant women with positive anti-TPO antibodies (n=28) and those with positive anti-Tg antibodies only (n=25) were analyzed separately, and both groups were compared with the autoimmune-negative control population (n=247). A family history of thyroid disease was more frequent in women with positive anti-TPO antibodies than in the control population (35.7% vs. 17.8%; p=0.024), with no differences between the two groups in terms of age, parity or baseline TSH levels (TSH 1.4±0.7 vs. 1.2±0.6mIU/l; p=0.328). No significant differences were found in any of the above variables between the pregnant women with positive anti-Tg antibodies alone and the control group. The baseline TSH concentration was 1.4±0.7mIU/l and 1.2±0.6mIU/l, respectively (p=0.123).

Variation of thyroid antibodies over timeThe laboratory tests were performed in the following gestational weeks (median [P25–P75]): week 9 (8–9) (n=300), week 15 (14–15) (n=266), week 25 (25–26) (n=98) and week 36 (36–37) (n=248).

The anti-TPO and anti-Tg antibody titers decreased significantly during pregnancy (Fig. 1). Between the first and last laboratory tests (gestational weeks 9 and 36, respectively), the anti-TPO antibodies decreased by 76.8%, with negative conversion in 6 women (21.4%), while the anti-Tg antibodies decreased by 80.7%, with negative conversion in 18 women (40%).

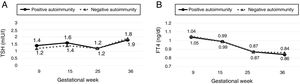

Variation of thyroid function over time and the appearance of hypothyroidismThe TSH and FT4 levels during pregnancy were similar in women with autoimmune thyroid disease and those with negative autoimmunity (Fig. 2). There were no significant differences in TSH and FT4 levels between the two groups in any of the gestational weeks in which laboratory tests were performed.

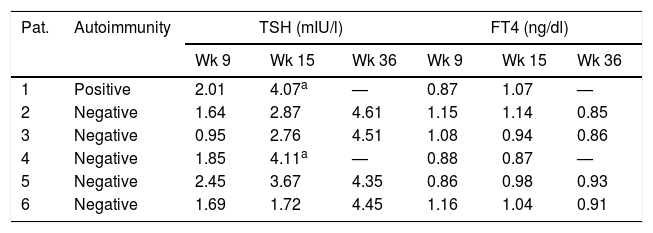

During follow-up, TSH increased to above 4mIU/l in one of the 53 pregnant women in the autoimmune-positive group (1.9%), and in 5 of the 247 women with negative autoimmunity (2%). Hypothyroidism was detected in week 15 in two of these women and in week 36 in the other four women. In no case did TSH increase to above 5mIU/l (Table 2). The pregnant women who developed hypothyroidism (n=6) had higher TSH levels at the start of pregnancy than the women who maintained TSH≤4mIU/l during pregnancy (TSH 1.8 vs. 1.3mIU/l; p=0.047), with no other significant differences.

Variation of thyroid function over time in the women who developed hypothyroidism during follow-up.

| Pat. | Autoimmunity | TSH (mIU/l) | FT4 (ng/dl) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wk 9 | Wk 15 | Wk 36 | Wk 9 | Wk 15 | Wk 36 | ||

| 1 | Positive | 2.01 | 4.07a | — | 0.87 | 1.07 | — |

| 2 | Negative | 1.64 | 2.87 | 4.61 | 1.15 | 1.14 | 0.85 |

| 3 | Negative | 0.95 | 2.76 | 4.51 | 1.08 | 0.94 | 0.86 |

| 4 | Negative | 1.85 | 4.11a | — | 0.88 | 0.87 | — |

| 5 | Negative | 2.45 | 3.67 | 4.35 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 0.93 |

| 6 | Negative | 1.69 | 1.72 | 4.45 | 1.16 | 1.04 | 0.91 |

TSH (mIU/l) and FT4 (ng/dl) levels in gestational weeks 9, 15 and 36 in the women who developed hypothyroidism during follow-up.

Pat.: patient; Wk: gestational week.

Twelve miscarriages were recorded during follow-up: one in the group of pregnant women with positive autoimmunity and 11 in the control group (1.9% vs. 4.5%; p=0.387). The incidence of preterm delivery was 7.5% and 5.2%, respectively (p=0.547). Likewise, no significant differences were found in the miscarriage or preterm delivery rates on separately comparing the women with positive anti-TPO antibodies and those with only positive anti-Tg antibodies versus the pregnant women with negative autoimmunity.

DiscussionThe results of our study show that pregnant women with positive thyroid autoimmunity and TSH<2.5mIU/l at the start of pregnancy have a minimal risk of developing hypothyroidism, similar to that seen in women with negative autoimmunity.

The prevalence of positive thyroid autoimmunity in pregnant women reported in the literature is highly variable.1,11 This variability is probably due to the different analytical methods used, the cut-off points employed, and the characteristics of the study population (ethnicity, iodine status, etc.). In our study, 17.7% of the pregnant women had positive thyroid antibodies in the first trimester. Of note is the observation that almost half of them were positive only for anti-Tg antibodies. Although the presence of thyroid antibodies has been associated in some studies with age and parity,7 we found no relationship between the presence of autoimmunity and these variables. Similarly to as was reported in previous studies,10,14,15 the anti-TPO and anti-Tg antibody titers decreased by about 80% during pregnancy, with negative conversion in 21% and 40% of the women, respectively. Therefore, in those cases where it is considered clinically appropriate, thyroid autoimmunity should be tested as early as possible in pregnancy, since the diagnostic usefulness of thyroid antibody testing in the second half of pregnancy is limited.

With regard to the main adverse events associated with thyroid autoimmunity (miscarriage and preterm delivery), we found no significant differences between the antibody-positive women and the control group. In this regard, it should be emphasized that the personal visit took place in gestational week 10 (range 6–18), and so in some cases miscarriage would have already occurred. The fact that the women included in our study presented baseline TSH<2.5mIU/l (and did not develop hypothyroidism during pregnancy) probably reflects the existence of mild or early forms of autoimmune thyroid disease.

Women with autoimmune thyroid disease are considered to be at an increased risk of developing hypothyroidism in pregnancy due to the inability of the thyroid gland to respond to the increased hormone production associated with pregnancy.16 Two previous studies in euthyroid pregnant women with positive autoimmunity recorded progression to hypothyroidism in close to 20% of the cases.15,17 The risk of hypothyroidism was higher in pregnant women with baseline TSH levels >2mIU/l and in those with high anti-TPO antibody titers. Based on the results of these studies, the clinical guides recommend periodic monitoring of thyroid function during pregnancy in women with autoimmune thyroid disease.11,18,19 However, the occurrence of hypothyroidism in our study was very low. In addition, hypothyroidism was detected at the end of pregnancy in most cases, and the TSH levels were <5mIU/l in all patients. The main differences between our study and the previous publications concern the baseline TSH cut-off point of the women on the one hand, and the prevalence of positivity of the different antithyroid antibodies on the other. With regard to the first point, the above-mentioned studies included women with basal TSH levels of up to 4mIU/l, while in our study pregnant women with TSH levels ranging from 2.5 to 4mIU/l were not included, because most of them started treatment with levothyroxine. With regard to antithyroid antibodies, the pregnant women in the studies published by Glinoer et al. and Negro et al. were predominantly positive for anti-TPO antibodies (84% and 100% of the women, respectively), while anti-Tg positivity predominated in our population. In addition, unlike the previous studies, our population was iodine-sufficient, and such improved iodination may have influenced a lesser frequency of progression to hypothyroidism. Two later studies also found a high frequency of hypothyroidism in women with autoimmune thyroid disease, this largely being explained by the definition of hypothyroidism used in both studies (i.e., TSH≥2.5mIU/l in the first trimester or ≥3mIU/l thereafter).20,21 Our findings are similar to those of a recent study in 140 Australian pregnant women with basal TSH<2.5mIU/l, in which none of the patients developed gestational hypothyroidism.10

ConclusionsIn our population, the risk of hypothyroidism in pregnant women with autoimmune thyroid disease and TSH<2.5mIU/l in the first trimester was minimal, and similar to that seen in women with negative autoimmunity.

The results obtained suggest the convenience of optimizing the follow-up of euthyroid women with autoimmune thyroid disease during pregnancy, based on the TSH levels in the first trimester. In this way, women at greater risk of developing hypothyroidism could be identified, and those at very low risk would not have to undergo needless monitoring.

Pregnant women with TSH<2.5mIU/l would not need further studies, because even if they had positive autoimmunity (known before pregnancy), the risk of developing hypothyroidism during pregnancy would be minimal.

In women with TSH levels ranging from 2.5 to 4mIU/l, the measurement of thyroid antibodies is recommended. If autoimmunity proves positive, treatment with levothyroxine may be considered (especially in the case of a history of adverse events in previous pregnancies, or assisted reproduction treatments).11 With regard to the risk of hypothyroidism in this group, our results do not allow for the drawing of conclusions (it was at the time of the study that the pregnant women with TSH>2.5mIU/l started treatment with levothyroxine). However, based on data from previous studies, these women would appear to be more at risk of developing hypothyroidism during pregnancy, and thyroid function monitoring is therefore advisable if such treatment is not started.

To sum up, women with autoimmune thyroid disease and TSH<2.5mIU/l in the first trimester of pregnancy have a minimal risk of gestational hypothyroidism; the monitoring of thyroid function therefore should not be required during pregnancy in these cases.

Authorship/collaboratorsM. Dolores Ollero, Javier Pineda, Juan Pablo Martínez de Esteban, Marta Toni and Emma Anda made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, and to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation. They also contributed to a critical review of the manuscript and to the final approval of the submitted version. Mercedes Espada contributed to the data analysis, as well as to the critical review and to the final approval of the submitted version of the manuscript.

FundingThis study was funded in part by the Endocrinology, Nutrition and Diabetes Foundation of Navarre (Fundación de Endocrinología, Nutrición y Diabetes de Navarra).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Thanks are due to the pregnant women who participated in the study, as well as to the midwives and gynecologists of Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra for their collaboration in this study.

Please cite this article as: Ollero MD, Pineda J, Martínez de Esteban JP, Toni M, Espada M, Anda E. Optimización del seguimiento de gestantes con enfermedad tiroidea autoinmune. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:305–311.