Automatic insulin delivery (AID) systems improve glycemic control and quality of life in individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Our aim was to assess the feasibility, effectiveness, and safety of switching from a sensor-augmented pump (SAP) to AID in T1D subjects at high risk of hypoglycemia.

Materials and methodsA manufacturer-led program consisting of three sessions was implemented. Over three days, all patients completed the first session in-person, in groups of 6–12 people, to receive device training. Subsequently, the automatic mode was activated virtually (session 2), followed by online data download (session 3). Glucometric outcomes were evaluated after one month, along with serious adverse events (SAEs), technical incidents, and perceived satisfaction.

ResultsThe switch was performed in 125 patients, 56.8% of whom were women, with a mean age of 44.1 ± 14.9 years. 99.2% (n = 124) initialized auto-mode. There was an increase in time in range 70–180 mg/dL (64.3 ± 11.3 vs. 74.7 ± 11.2; p < 0.001) and a decrease in time below 70 mg/dL (4.1 ± 3.9 vs. 2.0 ± 1.8; p < 0.001) (N = 97). Forty-one related calls were received, with 10 requiring in-person visits. Medtronic technical service handled 92 related calls (0.74 per patient), from 47 different users (37.6%). One event of severe hypoglycemia was recorded as an SAE. Perceived security and satisfaction with the switch process were high in 91% and 92% of patients, respectively.

ConclusionsMassive switch from SAP to AID in T1D patients at high risk of hypoglycemia is feasible and safe through a hybrid program conducted in collaboration with the manufacturer.

Los sistemas automáticos de administración de insulina (AID) mejoran el control glucémico y la calidad de vida en personas con diabetes tipo 1 (DT1). Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la viabilidad, efectividad y seguridad de un recambio masivo de sistema bomba-sensor (SAP) a AID en sujetos con DT1 y alto riesgo de hipoglucemia.

Material y métodosSe realizó un programa grupal e híbrido de 3 sesiones a cargo del fabricante. En tres días, todos los pacientes realizaron presencialmente la primera sesión en grupos de 6-12 personas para entrenar el uso del dispositivo. De forma virtual, se activó el modo automático (sesión 2) y la descarga de datos online (sesión 3). Se evaluaron resultados glucométricos tras un mes, así como eventos adversos graves (EAG), incidencias técnicas y satisfacción percibida.

ResultadosEl cambio de dispositivo se efectuó en 125 pacientes, 56,8% mujeres y edad media 44,1 ± 14,9 años. El 99,2% (n = 124) iniciaron modo automático. Se observó un aumento del tiempo en rango 70-180 mg/dL (64,3 ± 11,3 vs. 74,7 ± 11,2; p < 0,001) y una reducción del tiempo <70 mg/dL (4,1 ± 3,9 vs. 2,0 ± 1,8; p < 0,001) (N = 97). Recibimos 41 llamadas relacionadas, de las cuales 10 requirieron visita presencial. El servicio técnico de Medtronic atendió 92 incidencias relacionadas con el recambio (0,74 por paciente), provenientes de 47 usuarios (37,6%). Como EAG se registró una hipoglucemia grave. La seguridad y satisfacción percibidas con el proceso de cambio fue alta en el 91% y 92% de los pacientes.

ConclusionesEl recambio masivo de un sistema SAP a AID en pacientes con DT1 y alto riesgo de hipoglucemia es factible y seguro mediante un programa híbrido y en colaboración con el fabricante.

Automated insulin delivery (AID) systems have represented a paradigm shift in the treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM).1 These systems incorporate a control algorithm capable of automating the infusion of an insulin pump based on the integration of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data to maintain blood glucose levels within preset targets, minimizing user intervention.

In randomized clinical trials comparing with sensor-augmented pump (SAP) therapy, the use of AID systems has been shown to reduce HbA1c by 0.15%–0.33% and increase time in range (TIR) 70–180 mg/dL by 9%–12%, achieving a mean TIR close to 70% (65.0%–71.2%).2–6 These results have been achieved without increasing time in hypoglycemia or even reducing it. Furthermore, AID systems have demonstrated clear superiority over the standard T1DM treatment in our environment (multiple insulin doses and CGM), reducing HbA1c by 1.4% in patients with previous suboptimal glycemic control.7

The initiation of these devices in our environment has also been associated with rapid8 and sustained increases in TIR in real-life settings, regardless of prior treatment,9–12 and reductions in time spent in hypoglycemia9,11–13 and an improvement in hypoglycemia awareness.14 Additionally, the start of AID has been associated with a reduction in the neuropsychological burden associated with T1D13 and increased treatment satisfaction.15 These results have been observed across various AID systems currently available, without significant differences between them in the few comparative studies to date.16

Given the abundance of available scientific evidence, the most recent clinical practice guidelines recommend considering the initiation of this treatment in virtually any patient with T1DM capable of using it.17–19 Moreover, some guidelines from public health systems, such as the UK, already recommend the use of these devices in all individuals with suboptimal glycemic control (HbA1c ≥ 7.5%) or recurrent hypoglycemia,20 although specific evidence in populations at high risk of hypoglycemia has been scarcely evaluated.14,21,22

In Spain, approximately 20% of people with T1DM use continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) devices,23 but the numerous benefits observed with AID systems may drive an exponential increase in their use in the coming years. In the Diabetes Unit of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain which specializes in this type of therapy and actively follows 2000–2500 people with T1DM, the number of CSII users exceeds 500 patients. At the time of this study, approximately one-quarter of these patients had an integrated SAP system, while the use of AID systems was residual (< 5%). In a context like ours, evidence is needed on the feasibility, effectiveness, and safety of mass replacement programs to AID systems, which may be of particular interest, especially in subpopulations with recurrent hypoglycemia.

The primary endpoint of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a mass replacement program from SAP therapy with advanced features to AID systems in T1DM subjects at high risk of hypoglycemia in a reference diabetes unit. Secondary endpoints included assessing patient-reported satisfaction and safety during the process.

Materials and methodsStudy design and participantsWe conducted an observational, ambispective study at the Diabetes Unit of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. Adults with T1DM using SAP therapy with predictive low glucose suspend (Medtronic MiniMed® 640 G [Medtronic-Minimed, Northridge, CA, United States] with Guardian 3® sensor), initiated under public funding due to recurrent hypoglycemia (> 4 mild-to-moderate hypoglycemic events per week and/or ≥ 2 severe hypoglycemic events [requiring third-party assistance] in the last 2 years despite using an insulin pump) were included. The risk of hypoglycemia was minimized during follow-up for all of them through specific therapeutic education. Within the framework of a public tender at our center, SAP therapy for all these patients was mass-replaced with an AID system (MiniMed® 780 G with Guardian 4® sensor) over a 3-day period (March 13th–15th, 2023). Before the change, patients were systematically included in the study.

The mass therapy replacement process included a hybrid—in-person and virtual—program of 3 group sessions led by the manufacturer. The educational program was approved and supervised by our center therapeutic education team, with some members having participated in its implementation nationwide. The first session was in-person, in groups of 6–12 people, lasting 2–3 hours, and trained participants on the use of CSII and CGM, emphasizing the few technical differences from previous devices. The second session, which went on for 1 hour and was conducted online via videoconference after 1 week, in groups of 10–15 people, explained and initiated the automatic mode function. Since this was a population with a history of recurrent hypoglycemia, a conservative and generalized glucose target of 110 mg/dL and an active insulin time of 3 hours were set until further evaluation and adjustment by the usual medical team. Finally, the third session, which went on for 1 hour, was held virtually in groups of 10–20 people 1 week after the second session, addressing how to activate automatic data upload to the CareLink™ system every 24 hours via mobile device and, alternatively, how to perform it manually on a personal computer by connecting the CSII.

The study protocol was approved by our center Research Ethics Committee (HCB/2022/0473) and conducted following the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were included after providing informed consent.

ProceduresInitial patient characteristics were recorded at the time of inclusion (sex, age, diabetes duration, HbA1c). During the CSII replacement, glucometric and insulin usage data from the previous 14 days were downloaded. Data included sensor usage, total insulin units administered, mean glucose levels, coefficient of variation (CV), glucose management indicator (GMI), and percentage (%) of TIR, time in hypoglycemia (< 54 mg/dL [TBR < 54] and < 70 mg/dL [TBR < 70]), and in hyperglycemia (> 180 mg/dL [TAR > 180] and > 250 mg/dL [TAR > 250]). These variables, along with the percentage of time in automatic mode, were also collected for each patient after > 30 days of automatic mode activation. In this case, data were obtained directly from automatic uploads to the CareLink™ platform.

Additionally, patient satisfaction and safety with the replacement program were analyzed through questionnaires (Supplementary Table 1). After 1 month of AID system use, satisfaction with the new device was also assessed through questionnaires (Supplementary Table 2). In both cases, non-validated questionnaires were used due to the absence of alternatives for the replacement process and the interest in evaluating parameters linked to diabetes technology that are not currently assessed with validated questionnaires for treatment. Finally, severe adverse events (SAEs) (diabetic ketoacidosis or severe hypoglycemia) were prospectively collected during the 2-month replacement process, as well as the number of incidents attended by the manufacturer, hospital-related calls, and subsequent educational visits during this period.

EndpointsThe primary endpoint was to evaluate effectiveness in terms of glycemic control measured by TIR, including predefined secondary endpoints, such as the effectiveness in reducing the time spent in hypoglycemia (TBR < 70 and TBR < 54) and safety during the process measured by the presence of SAEs during the transition process. Additionally, viability was assessed by the percentage of successful transitions, as well as the number of technical incidents (handled by the manufacturer) and clinical incidents (handled at our center). Finally, patient satisfaction with the transition program and the AID system was evaluated.

Statistical analysisData are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or as percentages. Comparisons of continuous variables were performed using the Student’s t-test for paired samples. Statistical analysis was performed using R software, version 4.3.1, (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All statistical tests were 2-sided, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsA total of 125 subjects were included, 71 of whom were women (56.8%), with a mean age of 44.5 ± 12.3 years. The mean duration of T1DM was 27.9 ± 11.4 years, and the participants' mean HbA1c was 7.4 ± 0.8%. Participants had been using SAP therapy for a mean 3.9 ± 1.9 years. The mean number of severe hypoglycemia episodes in the last year was 0.14 ± 0.55, with a prevalence of ≥ 1 event in 8% (n = 10). Attendance at the 3 sessions was 96.0%, 97.6%, and 83.9%, respectively. Although the device change was effectively completed in all subjects, the AID mode was activated in 124 individuals (99.2%). Only 1 person chose not to start automatic mode and remained in manual mode by preference.

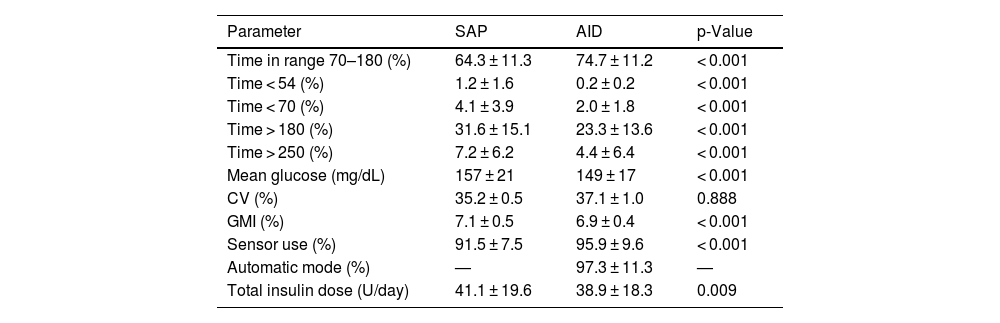

Glycemic data before and 1 month after the transition were obtained from 97 subjects (77.6%) (Table 1), while data could not be obtained for the rest due to issues with the mobile application or connectivity. The mean TIR went from 64.3 ± 11.3% up to 74.7 ± 11.2% (p < 0.001), with a decrease in TBR < 70 (4.1 ± 3.9 vs 2.0 ± 1.8; p < 0.001) and TBR < 54 (1.2 ± 1.6 vs 0.2 ± 0.2; p < 0.001). The GMI also dropped from 7.1 ± 0.5% down to 6.9 ± 0.4% (p < 0.001). These changes were achieved with a lower total daily insulin dose (41.1 ± 19.6 vs 38.9 ± 18.3; p = 0.009). After switching to AID therapy, patients remained in automatic mode for 97.3% of the time, and there was a significant increase in sensor usage (91.5 ± 7.5% vs 95.9 ± 9.6%; p < 0.001). Only 1 severe adverse event was recorded, a case of severe hypoglycemia attributed to an incorrect carbohydrate count during a previous meal and alcohol consumption. No ketoacidosis events were reported.

Glucometric data after 1 month of using the automated insulin delivery system vs baseline data using sensor-augmented pump therapy (n = 97).

| Parameter | SAP | AID | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time in range 70–180 (%) | 64.3 ± 11.3 | 74.7 ± 11.2 | < 0.001 |

| Time < 54 (%) | 1.2 ± 1.6 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | < 0.001 |

| Time < 70 (%) | 4.1 ± 3.9 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | < 0.001 |

| Time > 180 (%) | 31.6 ± 15.1 | 23.3 ± 13.6 | < 0.001 |

| Time > 250 (%) | 7.2 ± 6.2 | 4.4 ± 6.4 | < 0.001 |

| Mean glucose (mg/dL) | 157 ± 21 | 149 ± 17 | < 0.001 |

| CV (%) | 35.2 ± 0.5 | 37.1 ± 1.0 | 0.888 |

| GMI (%) | 7.1 ± 0.5 | 6.9 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Sensor use (%) | 91.5 ± 7.5 | 95.9 ± 9.6 | < 0.001 |

| Automatic mode (%) | — | 97.3 ± 11.3 | — |

| Total insulin dose (U/day) | 41.1 ± 19.6 | 38.9 ± 18.3 | 0.009 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

AID: automated insulin delivery; CV: coefficient of variation; GMI: glucose management indicator; SAP: sensor-augmented pump therapy.

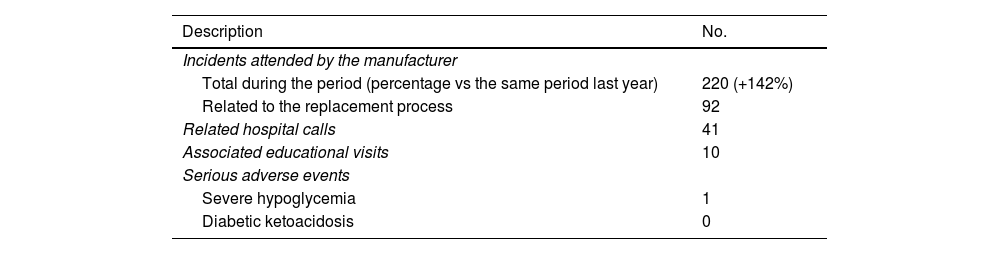

During the transition process, all technical and clinical incidents were systematically and prospectively collected (Table 2). At hospital level, 41 calls related to the transition were received from patients, 10 of whom needed to schedule a follow-up visit for additional therapeutic training. The Medtronic technical service handled a total of 220 patient incidents by phone, which is a 142% increase vs the same period the previous year. Of these, 92 incidents were related to the transition process (a mean of 0.74 incidents per patient) from 47 individuals (37.6%). Most incidents were CGM-related issues (51 incidents; 55.4%), followed by problems with the mobile app or data download (17 incidents; 18.5%), with the insulin pump (14 incidents; 15.2%), or with consumables or the inserter (10 incidents; 10.9%).

Clinical and technical incidents during the replacement process.

| Description | No. |

|---|---|

| Incidents attended by the manufacturer | |

| Total during the period (percentage vs the same period last year) | 220 (+142%) |

| Related to the replacement process | 92 |

| Related hospital calls | 41 |

| Associated educational visits | 10 |

| Serious adverse events | |

| Severe hypoglycemia | 1 |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 0 |

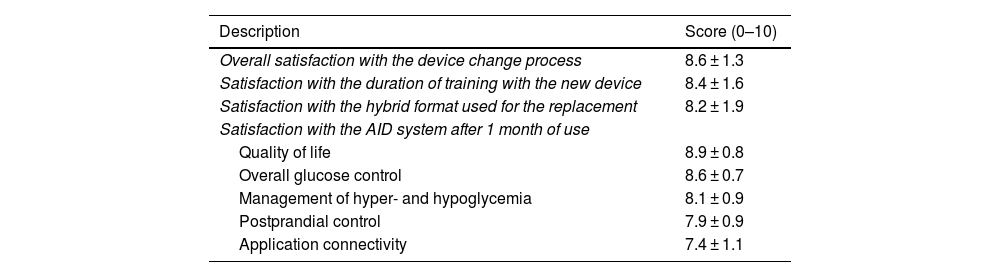

Regarding satisfaction data (Table 3), all patients completed the survey at the end of the program and expressed overall satisfaction with the transition process of 8.6 ± 1.3 (score: 0–10), rating training duration at 8.4 ± 1.6 (score: 0–10) and the hybrid format (in-person/virtual) at 8.2 ± 1.9. When asked about the likelihood of recommending the transition program (from 0 up to 10), the Net Promoter Score (NPS; percentage of 9–10 scores minus percentage of 0–6 scores) was 73%. After 1 month of using the AID system, patients (n = 84) reported a satisfaction of 8.9 ± 0.8 and 8.6 ± 0.8 (score: 0–10) in terms of quality of life and glycemic control, respectively. The lowest rating with the new system was associated with connectivity with mobile devices (7.4 ± 1.1; score: 0–10).

| Description | Score (0–10) |

|---|---|

| Overall satisfaction with the device change process | 8.6 ± 1.3 |

| Satisfaction with the duration of training with the new device | 8.4 ± 1.6 |

| Satisfaction with the hybrid format used for the replacement | 8.2 ± 1.9 |

| Satisfaction with the AID system after 1 month of use | |

| Quality of life | 8.9 ± 0.8 |

| Overall glucose control | 8.6 ± 0.7 |

| Management of hyper- and hypoglycemia | 8.1 ± 0.9 |

| Postprandial control | 7.9 ± 0.9 |

| Application connectivity | 7.4 ± 1.1 |

AID: automated insulin delivery.

In our cohort of T1DM patients at high risk of hypoglycemia undergoing SAP therapy, the large-scale transition to an AID system through a hybrid program (in-person and virtual) was feasible, effective, and safe. Additionally, patients were satisfied not only with the device change but also with the program format.

SAP therapy with predictive low glucose suspend (PLGS) has been shown to be effective in reducing hypoglycemia time without worsening HbA1c, both in clinical trials24 and real-life studies.25 Moreover, it has proven effective and safe in reducing hypoglycemia in high-risk populations with impaired hypoglycemia awareness.26 However, clinically significant hypoglycemia remains a non-negligible risk,27 and the development of new technologies is necessary to minimize it and achieve recommended control targets.28 In this regard, the advent of AID systems represents a promising strategy, although specific evidence for this patient subgroup is limited.21,29 In our study with a cohort of patients with recurrent severe hypoglycemia, switching from a SAP system to AID proved effective, rapidly halving the time spent in hypoglycemia and minimizing time spent < 54 mg/dL. Moreover, these changes were associated with a significant increase in mean TIR and high patient satisfaction with the new device.

Considering the multiple benefits observed so far in both glycemic control and quality of life with the introduction of AID systems, these devices are now recommended for virtually all T1D patients,18 and their use is expected to grow exponentially in the coming years, even within public health systems.30 However, in our setting, the use of insulin pumps is currently around 20% of individuals with T1DM,23 and there are no previous published experiences on the effectiveness and safety of large-scale AID system implementations in real life. Nonetheless, we do have previous successful experiences of specific programs for the rapid implementation of diabetes technology, such as CGM after its funding by the public health system.31–33 Our work adds new information on this topic and demonstrates that the large-scale implementation of AID systems, in subjects previously using SAP, can also be viable, safe, and effective. Through a 3-week 3-session hybrid group program in collaboration with the manufacturer, the simultaneous transition of therapy was successfully achieved. Additionally, perceived safety and satisfaction with the transition process were high (> 7/10) in 91% and 92% of patients, respectively. Despite the expected increase in technical incidents during this period, most were resolved by the manufacturer’s technical service and had no significant impact at hospital level. In an environment where additional resources are not always fully available to health care teams, collaboration between the Public Health System and the manufacturer in the preparation and execution of a transition program seems be a feasible and safe alternative.

Our study has some limitations. First, it is an observational study, and thus causality cannot be established. Additionally, glycemic data were obtained from 2 short periods, and we do not know if the positive findings can be extended over longer periods of time. Furthermore, it should be noted that glycemic data could not be obtained before and after the transition in all subjects, likely related to lower attendance at the third session of the program and incompatibility of some mobile devices to perform online data downloads automatically. Unfortunately, we also lack information on the time elapsed between the transition and the first visit with the medical team. Finally, the inclusion of a homogeneous sample from a single tertiary center may not be representative of other subgroups, geographic areas, or medical centers, limiting generalization to broader populations. Additionally, due to the study design, it is not possible to establish the feasibility and safety of a large-scale transition process without manufacturer collaboration.

Our study also a few strengths too. The first is that most data were collected prospectively, including incident logs from both the manufacturer and the hospital. Moreover, the robustness of the results is supported by the standardization of a program designed for subsequent implementation in clinical practice. Furthermore, this is the first study ever conducted to evaluate a large-scale program for transitioning from SAP to AID systems, and the first one to study the safety and efficacy of initiating an AID system specifically in a cohort of subjects with recurrent hypoglycemia.

In conclusion, the large-scale transition from a SAP to an AID system in patients with T1DM at high risk of hypoglycemia is feasible, effective, and safe through a hybrid program—in-person and virtual—and in collaboration with the manufacturer.

We wish to thank Medtronic for their help in obtaining and statistically analyzing the data that contributed to the drafting of this article.