Oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD) and malnutrition (MN) are highly prevalent among hospitalized patients, with significant clinical repercussions.

ObjectivesTo assess the prevalence, survival and factors associated with OD and MN in hospitalized patients with a high risk of OD.

MethodsA cross-sectional observational study with 82 patients aged ≥70 years and with the possibility of oral feeding admitted in 4 services of a third level hospital during 3 months. The Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 test (NRS-2002) was performed to detect nutritional risk and the volume-viscosity screening test (V-VST) for OD evaluation. Data were collected on the clinical suspicion of OD, days of hospital stay, the number of readmissions and other socio-demographic data.

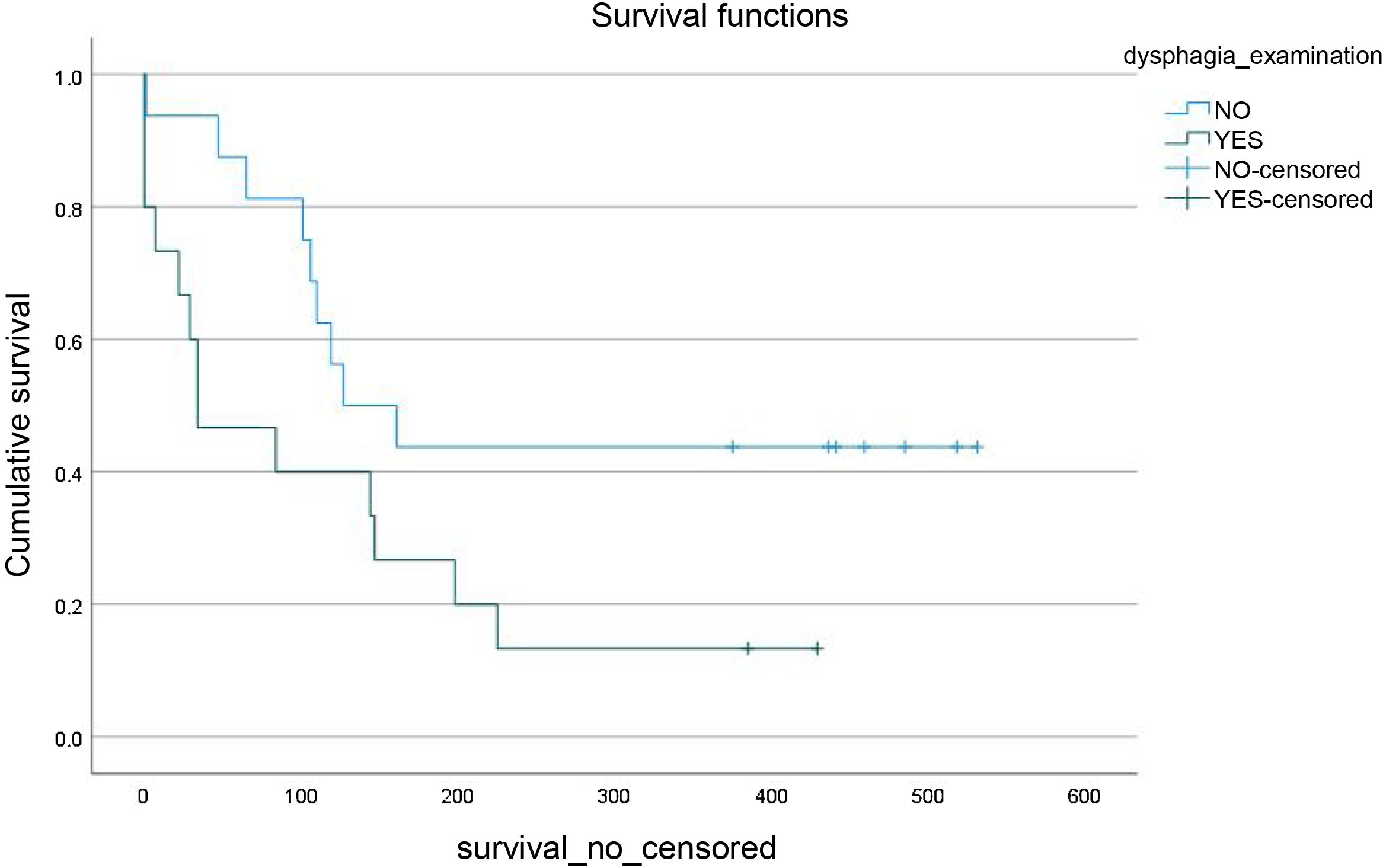

Results50.6% had OD and 51.9% MN. In 48.8%, there was underdiagnosis of OD. The median number of days of admission was higher among patients with MN (19.5 days vs 13 days, p = 0.02). Of the total readmissions, 70.8% had MN compared to 29.2% that did not (p = 0.03). Survival among patients who did not survive one year after admission was lower when OD was given (Sig. = 0.04).

ConclusionsMore than half of the population studied has OD, as well as DN, which increases the rate of readmission and decreases survival at the year of admission. Although there are specific screening methods, their use is not widespread, making it difficult to diagnose OD and its therapeutic intervention.

La disfagia orofaríngea (DO) y la desnutrición (DN) son muy prevalentes entre pacientes hospitalizados, las cuales tienen importantes repercusiones clínicas.

ObjetivosDeterminar la prevalencia, la supervivencia y los factores asociados a DO y DN en pacientes hospitalizados con alto riesgo de DO.

MétodosEstudio observacional transversal con 82 pacientes ≥70 años y con posibilidad de alimentación vía oral ingresados en 4 servicios de un hospital de tercer nivel durante un periodo de 3 meses. Se les realizó el test de cribado Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS-2002) para la detección de riesgo nutricional y el método de exploración clínica volumen-viscosidad (MECV-V) para valoración de la DO. Se recogieron datos sobre la sospecha clínica de DO, días de estancia hospitalaria, el número de reingresos y otros datos sociodemográficos.

ResultadosEl 50,6% presentaron DO y el 51,9% DN. En el 48,8% existió infradiagnóstico de DO. La mediana de días de ingreso fue mayor entre pacientes con DN (19,5 días vs 13 días, p = 0,02). Del total de reingresos, el 70,8% presentaban DN frente al 29,2% que no (p = 0,03). La supervivencia entre los pacientes que no sobrevivieron al año desde el ingreso era menor cuando se daba DO (Sig. = 0,04).

ConclusionesMás de la mitad de la población estudiada presenta DO, así como DN, lo cual aumenta la tasa de reingresos y disminuye la supervivencia al año del ingreso. A pesar de que existen métodos de cribado específicos, su uso no está extendido, dificultando el diagnóstico de la DO y su intervención terapéutica.

Oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD) is a set of clinical symptoms defined as difficulty effectively transporting a food bolus from the oral cavity to the oesophagus.1 The main risk factors are: age, dysfunction, sarcopenia, frailty, polypharmacy and comorbidities.2 The prevalence of OD among the elderly who live independently in the community is estimated to be between 30% and 40%.3 This increases to around 47.4% among patients hospitalised for an acute condition.4 Highest OD prevalence has been observed in neurological patients, although percentages vary depending on the neurological disease and population studied. Ferrero López et al. reported a dysphagia prevalence of 43% in patients with a history of cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and 75% in patients with Parkinson's disease.5 In other studies6,7 prevalences in Alzheimer's patients ranged from 32% to 45% if they were clinically assessed and 84%–93% if they were instrumentally evaluated. The study conducted by Cabré et al. found the prevalence in dementia patients to be 50%.8

OD is associated with impaired swallowing efficacy and safety, giving rise to complications such as malnutrition, dehydration, airway penetration and aspiration leading to respiratory infections, aspiration pneumonia and hospital admission.9 These complications significantly impact the health of elderly patients, affecting their nutritional status, functionality, morbidity, mortality and quality of life.10 This results in frailty and greater institutionalisation, increasing the mortality rate in this population.11

A robust relationship between OD and malnutrition (MN) has been established in the literature.1,5,10,12 In the elderly, food and fluid intake decrease due to age-related physiological factors, such as anorexia, chewing difficulty, cognitive impairment, and social, emotional and health-related problems.1 These health problems are often associated with conditions that entail increased nutritional requirements, a hypercatabolic state contributing to the onset of OD in elderly patients.5,12 The age-related relationship between loss of masticatory and swallowing strength and muscle mass, and changes in swallowing function that lead to the onset of OD (and consequently MN), is well established. While MN is accompanied by generalised loss of muscle mass, it also contributes to the onset of OD.1 MN-OD is a bidirectional relationship.

Both MN and OD reduce patient quality of life10 entail increased health costs13,14 due to a higher morbidity and mortality rate, and result in an increased length of hospital stay12 and higher institutionalisation rates. Early identification of OD and MN is vital in preventing complications and hospital readmissions. That is why nutritional screening, the detection of OD warning signs, and the application of validated OD diagnostic methods or more specific instrumental techniques are important.15 Treating dysphagia is simple, cost-effective and can prevent many complications if applied in time.2

The primary objective of this study is to determine the prevalence of OD and MN in hospitalised patients at high risk for OD. Its secondary objective is to identify the prevalence and association of these two syndromes with other related factors: the reason for admission, hospital stay, referral to the Dietetics and Clinical Nutrition Department (DCND), number of hospital readmissions and survival during the year following their inclusion in the study.

Material and methodsThis was a cross-sectional, observational pilot study on 82 patients admitted to the Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology (OST), Orthogeriatric (ORTG), Internal Medicine (IM) or Neurology and Neurosurgery (NRL/NRS) departments of a tertiary hospital. The enrolment period was three months (from November 2018 to January 2019). The study was approved by the hospital’s Independent Ethics Committee (PR 319/18). All patients and/or their legal guardians or families were informed about the study and signed the informed consent. The inclusion criteria were: patients admitted to the aforementioned departments aged 70 or over, except for neurological or neurosurgical patients whose age of inclusion was 18 years or above. Patients unable to feed orally were excluded.

The main study variables were: nutritional risk and the presence of OD. The Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS-2002) test was administered to evaluate patients' nutritional risk.16 OD at the time of the study was assessed using the Volume-Viscosity Swallow Test (V-VST).17 The patients were classified into two categories according to their NRS-2002 score: the presence of MN (≥3 points) and the absence of MN (<3 points).

With regards to OD, clinical suspicion of dysphagia before the evaluation was assessed, and the manifestation of OD was determined using the V-VST. "Prior dysphagia" was determined based on the clinical suspicion of OD either due to a diagnosis of OD by the medical team or due to the introduction of some change to the patient’s diet to prevent swallowing complications (thickening agents in fluids, diet without dual consistency foods or diet of a pasty consistency).

OD was determined following the V-VST standardised protocol. During the study, the test for higher volumes and lower viscosities was interrupted if any sign of compromised safety was observed. A positive test (manifestation of OD) was defined as any sign of impaired safety with the texture and volume tested.

As well as the main variables mentioned above, the following clinical-progression data were collected from each patient’s electronic medical record: the reason for admission (classified into seven categories: surgical procedure [SP] for fracture; SP for prosthesis replacement; sepsis; pneumonia; inflammation; CVA; exacerbation of the underlying condition), admission and discharge date, type of diet prescribed and referral (or not) to the Dietetics and Clinical Nutrition Department (DCND). Data on readmissions and emergency room visits within one year following their inclusion in the study were also collected from these patients.

After assessing OD, patients with a positive V-VST underwent a series of measures in accordance with the institutional protocol established by the DCND: adaptation of the patient's hospital diet, explaining the new clinical situation to the patient and their family, and explaining verbally and in writing the dietary recommendations to follow upon hospital discharge. If MN was also diagnosed, a nutritional intervention was performed to optimise the patient’s nutritional status during their hospital stay. This intervention involved prescribing oral nutritional supplements and/or providing recommendations for diet enrichment/adaptation during admission and discharge.

The data relating to the study patients were collected and encoded in accordance with the current regulations on personal data protection and the guarantee of digital rights. Data about the length of hospital stay and number of readmissions were obtained from the minimum primary data set (MBDS).

The sample size was not calculated as it is a pilot study. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software (version 24, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). The mean, median, 25th and 75th percentiles, and minimum and maximum values were used for the descriptive analysis of the recruited sample. To detect significant differences, the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables, and the Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, depending on the results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

ResultsThe data from 81 of the 82 patients invited to participate in the study were included. Of the 81 patients studied, 61.7% were women, and the median age was 81 years (IQR: 73−87 years). The median length of hospital stay was 16 days (IQR: 9−26 days). The overall sociodemographic data are shown in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample.

| Variable | n = 81 |

|---|---|

| Gender | n (%) |

| Female | 50 (61.7) |

| Male | 31 (38.3) |

| Age, yearsa | n (IQR) |

| 81 (73−87) | |

| Reason for admission | n (%) |

| SP fracture | 28 (34.6) |

| SP prosthesis replacement | 4 (4.9) |

| Sepsis | 5 (6.2) |

| Pneumonia | 7 (8.6) |

| Inflammation | 5 (6.2) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 17 (21.0) |

| Exacerbation of underlying condition | 15 (18.5) |

| Length of hospital stay (days)a | n (IQR) |

| 16 (9−26) | |

| Admission department | n (%) |

| OST | 21 (25.9) |

| ORTG | 17 (21.0) |

| IM | 23 (28.4) |

| NRL/NRS | 20 (24.7) |

| Prior dysphagia | n (%) |

| Yes | 31 (38.3) |

| No | 50 (61.7) |

| Dysphagia on examination | n (%) |

| Yes | 41 (50.6) |

| No | 40 (49.4) |

| Risk of malnutrition | n (%) |

| Yes | 42 (51.9) |

| No | 39 (48.1) |

| Referral to DCND | n (%) |

| Yes | 48 (59.3) |

| No | 33 (40.7) |

| Readmission | n (%) |

| Yes | 24 (29.6) |

| No | 57 (70.4) |

DCND: Dietetics and Clinical Nutrition Department; IM: Internal Medicine; NRL/NRS: Neurology/Neurosurgery; ORTG: Orthogeriatric; OST: Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology.

All patients completed the V-VST, which identified OD due to impaired safety at any volume of the three different textures tested in 50.6% (n = 41). Of this total, 42.5% were positive for liquid, 14.8% for nectar texture and just 3.8% for pudding texture. When the V-VST was performed, the nectar texture could be assessed in all patients (81), liquid texture in 73 and pudding texture in 79. Some 48.8% of the patients with OD had no prior suspicion of OD. In contrast, dysphagia was suspected in 25% of the patients without dysphagia before the dysphagia assessment (p = 0.02). Regarding MN, 56.1% of patients positive for OD also had a positive malnutrition screening. The sociodemographic data stratified according to OD are shown in Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics, stratified by dysphagia.

| Variable | Dysphagia YES (n = 41) | Dysphagia NO (n = 40) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) | 1.000 |

| Female | 25 (61) | 25 (62.5) | |

| Male | 16 (39) | 15 (37.5) | |

| Age, yearsa | n (IQR) | n (IQR) | 0.314 |

| 81.0 (73−89.5) | 80.5 (71.3−86) | ||

| Reason for admission | n (%) | n (%) | 0.533 |

| SP fracture | 14 (34.1) | 14 (35) | |

| SP prosthesis replacement | 1 (2.4) | 3 (7.5) | |

| Sepsis | 2 (4.9) | 3 (7.5) | |

| Pneumonia | 6 (14.6) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Inflammation | 2 (4.9) | 3 (7.5) | |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 9 (22) | 8 (20) | |

| Exacerbation of underlying condition | 7 (17) | 8 (20) | |

| Length of hospital stay (days)a | n (IQR) | n (IQR) | 0.846 |

| 15.0 (9−29) | 17.0 (9.5−25) | ||

| Admission department | n (%) | n (%) | 0.094 |

| OST | 6 (14.6) | 15 (37.5) | |

| ORTG | 11 (26.8) | 6 (15) | |

| IM | 14 (34.1) | 9 (22.5) | |

| NRL/NRS | 10 (24.4) | 10 (25) | |

| Prior dysphagia | n (%) | n (%) | 0.022 |

| Yes | 21 (51.2) | 10 (25) | |

| No | 20 (48.8) | 30 (75) | |

| Risk of malnutrition | n (%) | n (%) | 0.508 |

| Yes | 23 (56.1) | 19 (47.5) | |

| No | 18 (43.9) | 21 (52.5) | |

| Referral to DCND | n (%) | n (%) | 0.262 |

| Yes | 27 (65.9) | 21 (52.5) | |

| No | 14 (34.1) | 19 (47.5) | |

| Readmission | n (%) | n (%) | 0.809 |

| Yes | 13 (31.7) | 11 (27.5) | |

| No | 28 (68.3) | 29 (72.5) |

DCND: Dietetics and Clinical Nutrition Department; IM: Internal Medicine; NRL/NRS: Neurology/Neurosurgery; ORTG: Orthogeriatric; OST: Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology.

It was found that 51.9% (n = 42) of the participants were at risk of MN. The median length of hospital stay of malnourished patients was higher than those without MN (19.5 vs 13, p = 0.02). Regarding the relationship between OD and MN, 54.8% of patients who scored ≥3 points on the NRS-2002 had OD (p = 0.51). When considering those patients with a clinical suspicion of OD, 64.5% were at risk of MN versus 35.5% who were not (p = 0.11). The sociodemographic data stratified according to MN are shown in Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics, stratified by nutritional risk (NRS-2002).

| Variable | Nutritional risk YES (n = 42) | Nutritional risk NO (n = 39) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) | 1 |

| Female | 26 (61.9) | 24 (61.5) | |

| Male | 16 (38.1) | 15 (38.4) | |

| Age, yearsa | n (IQR) | n (IQR) | 0.06 |

| 82.5 (75−90) | 76 (71−85.5) | ||

| Reason for admission | n (%) | n (%) | 0.02 |

| SP fracture | 13 (30.9) | 15 (38.5) | |

| SP prosthesis replacement | 3 (7.1) | 1 (2.6) | |

| Sepsis | 2 (4.8) | 3 (7.7) | |

| Pneumonia | 6 (14.3) | 1 (2.6) | |

| Inflammation | 5 (11.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 4 (9.5) | 13 (33.3) | |

| Exacerbation of underlying condition | 9 (21.4) | 6 (15.4) | |

| Length of hospital stay (days)a | n (IQR) | n (IQR) | 0.02 |

| 19.50 (10−29) | 13 (8.5−21) | ||

| Admission department | n (%) | n (%) | 0.02 |

| OST | 13 (30.9) | 8 (20.5) | |

| ORTG | 8 (19.1) | 9 (23.1) | |

| IM | 16 (38.1) | 7 (17.9) | |

| NRL/NRS | 5 (11.9) | 15 (38.5) | |

| Prior dysphagia | n (%) | n (%) | 0.11 |

| Yes | 20 (47.6) | 11 (28.2) | |

| No | 22 (53.4) | 28 (71.8) | |

| Dysphagia on examination | n (%) | n (%) | 0.51 |

| Yes | 23 (54.8) | 18 (46.2) | |

| No | 19 (45.2) | 21 (53.8) | |

| Referral to DCND | n (%) | n (%) | 0.18 |

| Yes | 28 (66.6) | 20 (51.3) | |

| No | 14 (33.3) | 19 (48.7) | |

| Readmission | n (%) | n (%) | 0.03 |

| Yes | 17 (40.5) | 7 (17.9) | |

| No | 25 (59.5) | 32 (82.1) |

DCND: Dietetics and Clinical Nutrition Department; IM: Internal Medicine; NRL/NRS: Neurology/Neurosurgery; ORTG: Orthogeriatric; OST: Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology.

In total, 29.6% of patients were readmitted to the hospital at least once within one year of discharge. Of all the readmitted patients, 70.8% had MN at their inclusion in the study, versus 29.2% who did not (p = 0.03). Although a higher prevalence of OD was observed among readmitted patients (54.2% vs 45.8%, p = 0.81), these differences were not significant.

Some 59.3% of all patients received nutritional support following referral to the DCND. Overall, 67.7% of patients with suspected OD were referred to the DCND, similar to the proportion of patients with OD confirmed by the V-VST (65.8%) and patients at risk of OD (66.7%). The breakdown by department is shown in Table 4.

The survival analysis revealed that having OD was associated with lower survival from the first days versus not having OD (p = 0.045) among patients who died within one year of inclusion in the study (Fig. 1).

Of those patients who did not survive one year following their inclusion in the study, 63.6% had prior OD versus 36.4% who did not (p = 0.009). In total, 59.1% of patients who did not survive one year had OD confirmed by V-VST, with no significant differences found compared to those patients who did not have OD. A higher prevalence of patients who died during the first year had a positive malnutrition screening result (63.6%), but these results were not significant. The factors associated with survival are shown in Table 5.

Analysis of factors associated with survival at 12 months after discharge.

| Variable | N subtotal (n = 81) | Survival YES (n = 59) | Survival NO (n = 22) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) | 1.000 | |

| Female | 50 | 36 (61.0) | 14 (63.6) | |

| Male | 31 | 23 (39.0) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Prior dysphagia | n (%) | n (%) | 0.009 | |

| Yes | 31 | 17 (28.8) | 14 (63.6) | |

| No | 50 | 42 (71.2) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Dysphagia on examination | n (%) | n (%) | 0.455 | |

| Yes | 41 | 28 (47.5) | 13 (59.1) | |

| No | 40 | 31 (52.5) | 9 (40.9) | |

| Risk of malnutrition | n (%) | n (%) | 0.221 | |

| Yes | 42 | 28 (47.5) | 14 (63.6) | |

| No | 39 | 31 (52.5) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Referral to DCND | n (%) | n (%) | 0.446 | |

| Yes | 48 | 33 (55.9) | 15 (68.2) | |

| No | 33 | 26 (44.1) | 7 (31.8) | |

| Readmission | n (%) | n (%) | 0.099 | |

| Yes | 24 | 14 (23.7) | 10 (45.5) | |

| No | 57 | 45 (76.3) | 12 (54.5) |

OD is one of the most underdiagnosed conditions among the elderly.9,10,13,18 This study highlighted this high rate of underdiagnosis, given that 48.8% of patients with no clinical suspicion of OD had a confirmed positive diagnosis of OD after clinical examination. This is consistent with the results obtained in the study by Cabré et al.4 in which the characteristics of the population studied were similar to ours. In contrast, the prevalence of OD may sometimes be overestimated since delirium on admission or other mental illnesses that present with swallowing difficulty are common in this population. These patients no longer manifest OD once the acute situation is resolved.6 In addition, a correct diagnosis can also be complicated by a lack of specialised personnel trained in examination techniques, as is the case with the V-VST.6

In our study, more than half of the participants had some form of impaired safety of swallow. More patients manifested OD to thin liquids (42.5%), followed by OD to nectar texture (14.8%), which suggests a more severe degree of OD. In total, 3.8% of the patients in the sample studied had OD to pudding texture. This latter percentage could be due to impaired efficacy of swallow, such as difficulty clearing the throat, which results in greater pharyngeal residue that may lead to impaired safety. Alternatively, it could also be due to other types of dysphagia with a more mechanical or obstructive component (related to solids) than a neurological component, as the latter is more related to OD to liquid textures.19 In this study, obstructive OD leading to impaired efficacy were not studied in greater detail as the exclusive focus was on impaired safety of swallowing. Our series of data obtained is consistent with previous studies, detecting a similar prevalence of OD in hospitalised patients with similar characteristics.4,13

Regarding the prevalence of MN, our results are similar to or higher than the prevalence found in other studies12,13 with MN diagnosed in more than half of the population studied. Comparing our results with those from the PREDyCES study, both of which used the NRS-2002 to diagnose MN, our prevalence of MN was higher as the population was predominantly elderly (≥70 years of age, except for patients attending the Neurology/Neurosurgery department); a population that is more prone to MN.12,20 In contrast, the PREDyCES study included any patient aged 18 years or over admitted to any of the selected hospitals. Moreover, there is also a marked difference in the total number of study participants (82 vs 1597). It, therefore, seems that MN is associated with age, as was found in our study, in which the mean age of malnourished participants was higher than patients without MN, despite not being statistically significant (82.5 years vs 76 years, p = 0.06). This is due to natural changes that occur at this stage of life, such as: anorexia of ageing, chewing problems, cognitive impairment and social, emotional and health-related problems1 that cause the nutritional status of elderly individuals to deteriorate. If the increased nutritional requirements attributable to the disease are added to this, MN is very prevalent in this population group.1

The relationship between OD and MN has been corroborated in several studies10,13,18,21 with one being the only independent triggering factor for the other and vice versa.1,10,22 In our study, almost 30% of the population had both OD and MN simultaneously. The prevalence of OD increased to 54.8% among patients with MN. Similarly, 56.1% of patients with OD also had MN. These results were not statistically significant, and it would be advisable to expand the study population. However, they are similar to the results of other studies that show the robust relationship between OD and MN.13,23

Several studies show that OD and/or MN is a mortality risk factor within one year of hospital discharge.13,14,24 Our study found that the mortality of patients with OD was already higher from the first days compared to patients who did not have OD. There was also a higher prevalence of mortality in patients with prior OD. This can be explained by considering that these patients could have a much more evident and, therefore, more severe form of OD (even before the clinical examination), and they would therefore have a poorer general and nutritional status, as confirmed in other studies.8,25 Our study found that having nutritional risk is also a determining factor for higher mortality during the first year. Although not statistically significant findings, they align with those of other studies.12,25

At the same time, the prevalence of readmissions by each of the different variables studied was also observed. Almost 30% of patients were readmitted to hospital at least once within one year of their inclusion in the study. Of all readmitted patients, approximately 70% had MN, while the length of hospital stay was also longer in patients with MN than without. As such, similar conclusions can be drawn as those by Palma Milla et al.26 following their systematic review, who found that MN during hospital admission was associated with a significant increase in morbidity and mortality and higher healthcare costs attributable to complications, greater treatment complexity, more extended hospital stay and a higher number of readmissions. Regarding dysphagia, the prevalence of OD was higher in readmitted patients than in those who were not. All these findings lead us to conclude that a timely nutritional intervention, both in patients with just OD or MN as well as with both, is a cost-effective solution12,24,26 that would reduce hospital costs12,24,26 as well as increase patient survival and quality of life.

The involvement of the DCND was also analysed in this study. Some 59.3% of all patients were referred to the DCND by the medical team for nutritional assessment. It was further observed that more than 60% of patients with clinical suspicion of OD, confirmed OD or MN were referred to the DCND. These high percentages may very well be explained by the types of the medical department involved in the study, which is accustomed to treating geriatric patients afflicted by multiple conditions, and are therefore more sensitive to detecting both OD and MN than other specialities due to the patients' clear needs. The Orthogeriatric and Internal Medicine departments accounted for the highest number of referrals, with 33.3% of the total, followed by Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology (20.8%), with Neurology/Neurosurgery lagging somewhat behind (12.5%). Despite the well-established relationship and prevalence of OD in neurological diseases2,8,10 this department requested fewer referrals to the DCND than any other. This may be because the DCND referral criteria are unclear or because the healthcare personnel responsible for the patient do not deem it necessary.

The strengths of this study are that it was conducted in a tertiary hospital with an elderly population and a higher prevalence of OD and MN, and it used validated scales. The NRS-2002 nutritional screening test was used rather than the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), as it is the tool recommended by the European Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) for hospitalised patients and because of its simplicity. It was therefore considered a more appropriate tool for screening geriatric patients with acute conditions.27,28 However, it also has some limitations, such as not having calculated the sample size as it was a pilot study and having conducted the study in a single centre. Future studies are required to confirm our results.

In conclusion, the prevalence of OD and MN among hospitalised geriatric patients is high, and there is a close relationship between these two conditions. Correctly diagnosing OD continues to be challenging owing to a failure to include specific screening tests as part of the initial assessment of high-risk patients upon hospital admission and due to a lack of trained/informed personnel. Suffering from OD and/or MN is associated with increased mortality within one year of hospital discharge. OD affects patients' nutritional status, and patients need to be assessed by professionals such as dieticians and nutritionists to adapt their diet correctly and to provide appropriate nutritional support to minimise complications associated with the late detection of both OD as well as MN, with the additional healthcare costs that this entails.

FundingThis research has not received specific funding from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestNone.