Serum cortisol levels within the first days after pituitary surgery have been shown to be a predictor of post-surgical adrenal insufficiency. However, the indication of empirical glucocorticoids to avoid this complication remains controversial.

The objective is to assess the role of cortisol in the early postoperative period as a predictor of long-term corticotropic function according to the pituitary perisurgical protocol with corticosteroid replacement followed in our center.

MethodsOne hundred eighteen patients who underwent surgery in a single center between December 2012 and January 2020 for a pituitary adenoma were included. Of these, 54 patients with previous adrenal insufficiency (AI), Cushing's disease, or tumors that required treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids (GC) were excluded. A treatment protocol with glucocorticoids was established, consisting of its empirical administration at rapidly decreasing doses, and serum cortisol was determined on the third day after surgery. Subsequent adrenal status was assessed through follow-up biochemical and clinical evaluations.

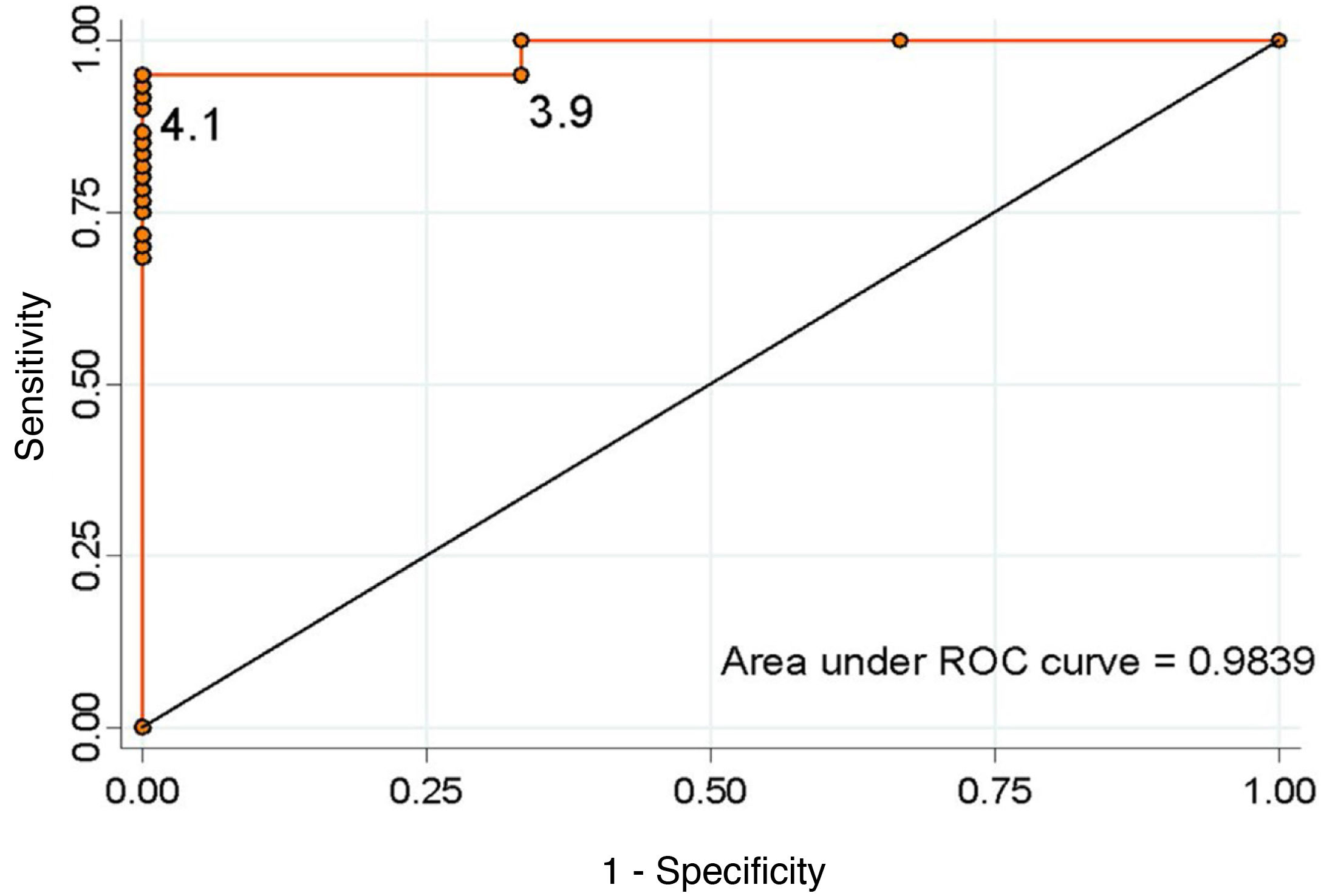

ResultsOut of the 64 patients treated, there were 56 macroadenomas and 8 microadenomas. The incidence of adrenal insufficiency after pituitary surgery was 4.7%. The optimal cut-off value that predicted an adequate corticotropic reserve, taking into account the best relationship of specificity and sensitivity, was ≥4.1 μg/dl for serum cortisol on the third day (sensitivity 95.1%, specificity 100%).

ConclusionSerum cortisol on the third day predicts the development of adrenal insufficiency. We suggest a cortisol cut-off point of ≥4.1 μg/dl on postoperative on the third day after surgery as a predictor of the adrenal reserve in the long-term.

La determinación de cortisol sérico los primeros días tras la cirugía hipofisaria ha demostrado predecir la insuficiencia adrenal (IA) posquirúrgica. Sin embargo, es controvertida la conveniencia de administrar empíricamente glucocorticoides (GC) para prevenirla. El objetivo es analizar la utilidad del cortisol en el postoperatorio temprano como predictor de la función corticotropa a largo plazo, siguiendo el protocolo periquirúrgico hipofisario con reemplazo de corticoides establecido en nuestro centro.

MétodosSe incluyeron 118 pacientes intervenidos en un único centro entre diciembre 2012 y enero 2020 por un adenoma hipofisario. De estos, se excluyeron 54 pacientes por IA previa, enfermedad de Cushing o aquellos que precisaron tratamiento con GC a altas dosis. Se estableció un protocolo de tratamiento con GC que consistía en su administración empírica a dosis rápidamente descendentes y se determinó el cortisol sérico al tercer día poscirugía. Se realizaron sucesivas reevaluaciones de la función adrenal según criterios clínicos y bioquímicos.

ResultadosDe 64 pacientes, 56 presentaban macroadenomas y 8 microadenomas. La incidencia de IA tras cirugía hipofisaria fue del 4,7%. El valor de corte óptimo que predijo una adecuada reserva corticotropa, teniendo en cuenta la mejor relación de especificidad y sensibilidad, fue de ≥ 4,1 μg/dl para el cortisol sérico al tercer día (sensibilidad 95,1%, especificidad 100%).

ConclusiónEl cortisol sérico al tercer día predice el desarrollo de IA. Sugerimos un punto de corte de cortisol sérico al tercer día de la cirugía de ≥ 4,1 μg/dl como predictor de una adecuada reserva adrenal a largo plazo.

Pituitary tumours account for 16.5% of brain tumours and are the second most common type of brain neoplasm.1 They can be found incidentally in up to 20% of the population.2 Surgical treatment of these lesions is generally indicated in secreting adenomas (except prolactinomas, whose first-line treatment is pharmacological) and clinically symptomatic non-secreting adenomas. Surgery should be considered in cases of pituitary apoplexy, Rathke's cleft cysts, craniopharyngiomas and other parasellar tumours.

Nowadays, the technique of choice is transsphenoidal surgery. It is only in very selected cases (large tumours, fibrous consistency, suprasellar invasion, etc.) that a transcranial approach might be necessary.3 With endoscopic access, structures can be visualised that could remain hidden in the direct light of microscopy and, although its superiority is yet to be determined, this makes it the most widely used approach.4 One of the most common postoperative endocrine complications, with a reported incidence of 5.5%, is the development of adrenal insufficiency (AI).5

Measurement of serum cortisol in the first days after surgery has been shown to predict the development of postoperative AI.6 However, the advisability of empirically administering glucocorticoids (GC) to prevent symptoms and complications deriving from hypocortisolism remains subject to debate. As far back as 2002, Inder and Hunt7 recommended avoiding GC in selective adenomectomy and adequate preoperative adrenal function, reserving them for more extensive resections or in the case of previous AI. However, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) continues to recognise the empirical administration of GC as an equally valid alternative in all cases.8 Treatment protocols with GC, at highly variable doses, are still used in many hospitals, probably due to the lack of trials comparing the two options.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the discriminatory capacity of serum cortisol on day three after surgery as a predictor of long-term corticotropic function in patients undergoing pituitary surgery, following the perioperative protocol for corticosteroid replacement established in our centre.

Material and methodsWe evaluated 118 patients who had undergone transsphenoidal endoscopic surgery at the Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra [Hospital Complex of Navarre], from December 2012 to January 2020, and had at least one year of follow-up.

We excluded patients with Cushing's disease (n = 11), previous AI (n = 15), pituitary apoplexy (n = 4) and those who needed higher doses of GC due to perioperative complications (n = 7). Also not included were 15 patients with pituitary tumours of lineages other than pituitary adenomas (4 craniopharyngiomas, 4 meningiomas, 3 Rathke's cleft cysts, 2 chordomas, 1 germinoma and 1 osteosarcoma) and two patients due to lack of data at one year after the intervention. In the end, 64 patients were included.

Preoperative study and surgical treatmentAn evaluation of the integrity of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis was performed preoperatively in all patients. In some cases, the evaluation of the corticotropic and somatotropic axes required functional tests, according to routine clinical practice.

A transsphenoidal adenomectomy with transnasal access was carried out in all cases, performed by the same surgical team. The resected material was analysed by pathology for histological and immunohistochemical study. The degree of tumour resection performed was defined as total or partial based on the postoperative MRI findings.

Surgical and postoperative managementA treatment protocol was established that consisted of empirical administration of GC at rapidly decreasing doses and early reassessment with criteria for indicating replacement therapy at discharge based on the postoperative cortisol level.

All the patients received perioperative coverage with hydrocortisone. On the day of the intervention (day 0), they received 50 mg of intravenous hydrocortisone/every 8 h, on day 1 post-intervention 25 mg/every 8 h and on day 2, they were given 30 mg of oral hydrocortisone at 8 a.m. Basal cortisol was analysed on day three after the intervention, after which 30 mg of oral hydrocortisone was once again administered. If the patient's cortisol level was <5 μg/dl, they continued on 30 mg of hydrocortisone a day in two divided doses, from 5 to <10 μg/dl, they were given 20 mg of hydrocortisone in a single morning dose, from 10 to <16 μg/dl, they were given 10 mg, and ≥16 μg/dl, no treatment was indicated. This treatment was continued after discharge. In all cases, they received verbal and written instructions on managing AI in stressful situations and advice for recognising the symptoms. Serum cortisol was determined using the ARCHITECT Cortisol® system (Abbott, Illinois, USA), which uses chemiluminescent macroparticle immunoassay (CMIA) technology.

The corticotropic axis was reassessed on an outpatient basis at four weeks and then every three months during the first year, assessing the discontinuation of hydrocortisone treatment on an individual basis. Basal serum cortisol was measured at each visit. If this was less than 5 μg/dl, treatment was continued, but if it was greater than 12 μg/dl it was discontinued. If serum cortisol was between 5 and 12 μg/dl, an ACTH test was performed, with a cut-off value >18 μg/dl to discontinue treatment. We defined AI as when the indication for replacement therapy continued one year after the intervention.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables are described by frequencies and percentages for each of their categories, and quantitative variables by central measures (mean, median) with measures of dispersion (standard deviation and interquartile range). The normality of the variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative variables. The ROC curve was calculated to define the cut-off values. For the statistical analysis, the STATA® program, version 12, was used. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsBaseline characteristics of the sampleA total of 64 patients were included, 31 (48.4%) of whom were male. Mean age was 55.3 ± 14.1 years and 56 (87.5%) were macroadenomas. In terms of the type of lesion, 34 (53.2%) were nonfunctioning adenomas, 21 (32.8%) somatotrophs, 5 (7.8%) thyrotrophs and 4 (6.2%) lactotrophs. Other baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the sample.

| Number of patients | 64 |

| Male | 31/64 |

| Age, mean ± SD | 55.3 ± 14.1 |

| Type of tumour (%) | |

| Nonfunctioning adenoma | 34 (53.2%) |

| Somatotroph | 21 (32.8%) |

| Thyrotroph | 5 (7.8%) |

| Lactotroph | 4 (6.2%) |

| Size (mm), mean ± SD | 21.8 ± 10.4 |

| Macroadenoma | 56/64 |

| Invasion of the cavernous sinus | 27/64 |

| Preoperative hormonal changes (%) | |

| Hyperprolactinaemia | 22 (34.4%) |

| GH deficiency | 4 (6.2%) |

| Secondary hypogonadism | 13 (20.3%) |

| Secondary hypothyroidism | 5 (7.8%) |

| Diabetes insipidus | 0 |

| Preoperative visual impairment (%) | 24/64 |

| Re-intervention (%) | 3/64 |

| Type of surgery | |

| Endoscopic | 59/64 |

| Microscopic | 5/64 |

| Perioperative complications (%) | |

| CSF fistula | 3 (4.7%) |

| Meningitis | 1 (1.6%) |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | 0 |

| Permanent diabetes insipidus | 2 (3.1%) |

| GH deficiency | 0 |

| Secondary hypogonadism | 0 |

| Secondary hypothyroidism | 3 (4.7%) |

CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; GH: growth hormone; SD: standard deviation.

The endoscopic technique was used in 59 patients (92.2%), with only five patients being accessed by microscopy. The resection was total in 38 patients (59.4%) and subtotal or partial in 26 (40.6%). Prior to surgery, 24 patients (37.5%) had visual impairment. Of these, there was partial improvement of the ophthalmological symptoms in 12 cases (50%), complete resolution in six (25%) and no change in the remaining six (25%). None of the patients experienced worsening as a result of surgery and none developed visual impairment as a new complication. The results of the histological and immunohistochemical study of the adenomas operated on are shown in Table 2.

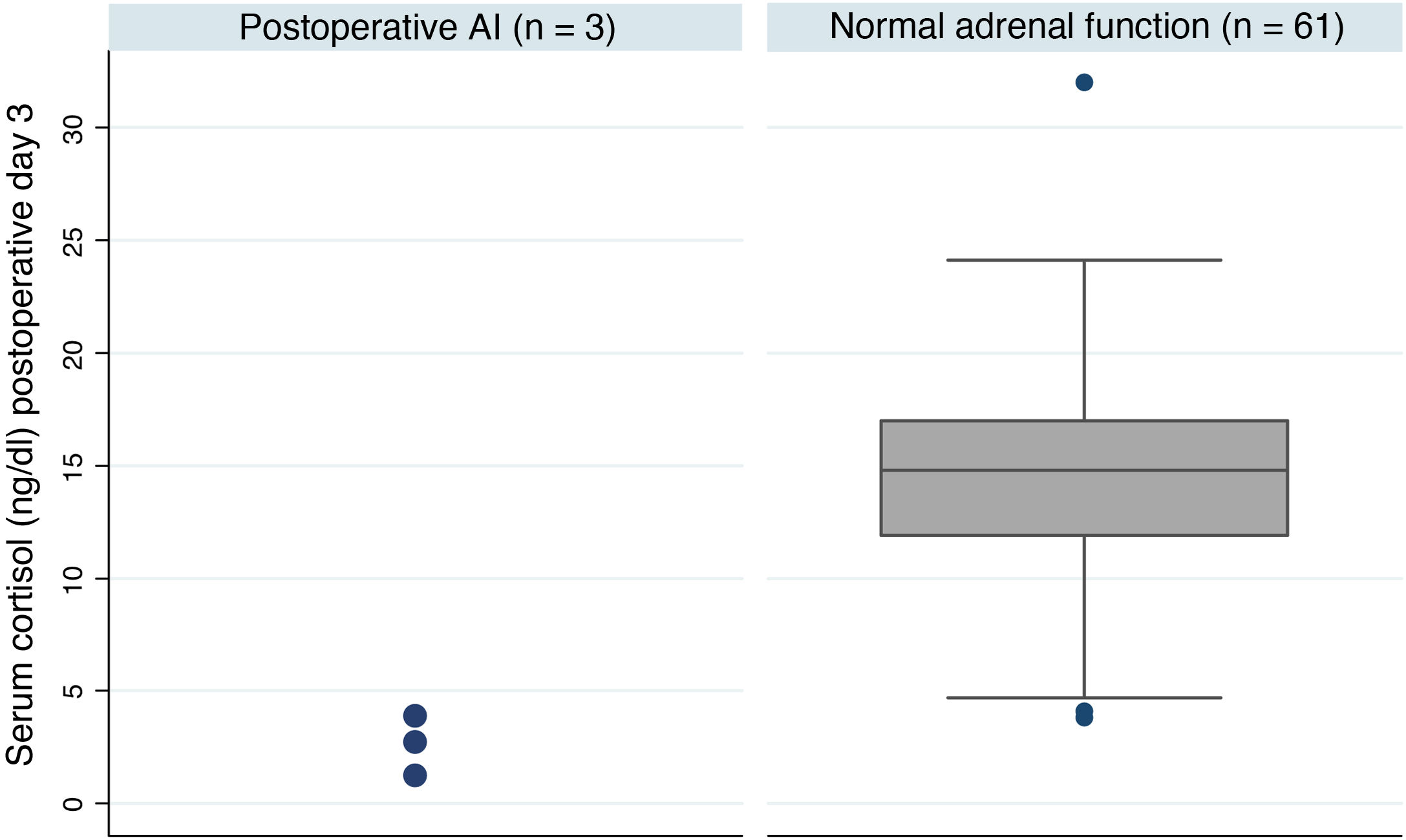

Postoperative adrenal insufficiencyOf the 64 patients, three were still on treatment with hydrocortisone one year after the intervention, which represents an AI rate of 4.7% at our centre. These patients had much lower postoperative basal cortisol levels than patients with adrenal reserve (median [IQ]; 2.8 [1.2-3.9] vs 14.8 [11.9-17.0] p = 0.005) (Fig. 1). Table 3 shows a summary of the characteristics of these patients. One of the three cases received treatment with pituitary radiotherapy one month after the intervention due to data indicating aggressiveness.

Summary of the characteristics of the patients who developed AI

| No. | Gender, age | Type of lesion | Max. tumour diameter | Type of surgery | Preoperative deficiency | Cortisol day 3 (ng/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | M, 70 | Prolactinoma | 18 mm | Endoscopic | None | 1.2 |

| 2 | M, 50 | GH-secreting | 8 mm | Endoscopic | None | 2.8 |

| 3 | M, 40 | Nonfunctioning | 14 mm | Endoscopic | Secondary hypothyroidism | 3.9 |

AI: adrenal insufficiency; GH: growth hormone; M: male.

Following our centre's protocol, 45 patients (70.3%) continued taking the discharge hydrocortisone therapy until outpatient reassessment. In 30 of the 45 cases, the hydrocortisone dose was 10 mg, in six patients it was 20 mg and nine were prescribed 30 mg due to having levels <5 μg/dl. None of the patients developed signs or symptoms consistent with AI during the treatment or after it was discontinued.

Considering the values proposed by our protocol as the cut-off point, a serum cortisol level ≥5 μg/dl has a sensitivity of 90.1% and a specificity of 100% to detect the adequate functionality of the pituitary-adrenal (PA) axis (positive predictive value [PPV] 100%, negative predictive value [NPV] 33.3%). In contrast, a cut-off point ≥16 μg/dl has a sensitivity of 31.1% and a specificity of 100% (PPV 100% and NPV 6.7%). None of the patients discharged without treatment developed AI during follow-up. We calculated the ROC curve (Fig. 2), which showed that the optimal cut-off value to ensure normality of the corticotropic axis, taking into account the best specificity and sensitivity ratio, was ≥4.1 μg/dl (sensitivity 95.1%, specificity 100%, PPV 100% and NPV 50%).

DiscussionThis study shows that the blood cortisol level on day three after surgery is an adequate predictor of adrenal reserve, with a sensitivity of 95.1% and a specificity of 100% for a cut-off point of ≥4.1 μg/dl.

In the 1950s, Lewis et al and Fraser et al9,10 published cases of patients with PA axis dysfunction who underwent surgery without having received GC therapy and subsequently died. Since then, stress-dose GC protocols have been introduced for all patients undergoing pituitary surgery. In 2002, Inder and Hunt7 published a guide on perioperative management with GC, in which they recommended not administering GC in selective adenomectomies and normal preoperative adrenal function. Following on from that guide, numerous studies have shown the safety of this alternative. McLaughlin et al11 only administered GC if serum cortisol on postoperative day 1 or 2 was below 4 μg/dl, while Wentworth et al12 started treatment if serum cortisol on day 1, 2 or 3 was below 9 μg/dl. The recent protocol for the management of pituitary surgery in a Spanish referral hospital for pituitary tumours also proposes only administering GC for cases in which the axis function cannot be tested preoperatively, in pituitary apoplexy or in patients already on long-term GC.13 In our study, all patients were administered GC and we had no control group with which to draw conclusions, so we are unable to show any evidence in this regard. However, only 4.7% of the patients developed AI and in all cases they had cortisol levels <4.1 μg/dl, which allows early detection of hypocortisolism and early treatment. These data could support the argument for not treating empirically.

Another factor that remains open to debate in these protocols is the best time to determine serum cortisol. Marko et al14 investigated the utility of serum cortisol immediately after surgery (60 to 180 min post-intervention). They found that values >15 μg/dl predicted the functionality of the axis (sensitivity 98%, PPV 99%), and that cortisol in the recovery room was more accurate than cortisol levels on day 1 post-intervention.15 Later, Qaddoura et al16 compared the measurements in postoperative recovery and those of days 1, 2 and 3 post-intervention. Again, the measurement taken on the day of the intervention was the one that best characterised the functionality of the axis. Tested in the recovery room, levels above 27.46 μg/dl had 100% sensitivity and 70% specificity. Different serum cortisol thresholds were determined for each day.

These studies contend that measuring cortisol when the patient is subject to conditions of great stress is the best time to identify the difference between those who preserve an adequate adrenal response and those whose function has been damaged. The half-life of ACTH is 10 min, while that of cortisol is about 66 min. Serum cortisol should be measured after 1-2 mean half-lives of cortisol to detect the pituitary response, which is at least one hour after tumour resection. Similar strategies are being used to predict remission after surgery in Cushing's disease.17 Early measurement can also help towards the early discharge of the patient. In our study, serum cortisol on day three was a good predictor of the development of AI, with a sensitivity of 95.1% and a specificity of 100% for serum cortisol <4.1 μg/dl. These data are similar to studies performed even in the recovery room.

There is also no consensus in the different studies on the cut-off point that predicts an adequate adrenal reserve. According to our protocol, nine patients received 30 mg of hydrocortisone as treatment for cortisol levels <5 μg/dl. This was appropriate because, of these nine patients, three developed AI, which they did not recover from in the long term. If their cortisol levels were 5-10 μg/dl, they received 20 mg of hydrocortisone and if 10-16 μg/dl, they were given 10 mg of hydrocortisone. In these two groups, the treatment could have been omitted as none of the patients developed AI. Such overtreatment is not without risks, including hyperglycaemia, hypertension and delayed healing of the surgical wound. A valid alternative would be clinical monitoring of these patients, treating them if they develop hypotension, nausea, vomiting, headache or anorexia. We suggest a value of ≥4.1 μg/dl in asymptomatic patients as a predictor of adequate adrenal reserve.

Late hypopituitarism is one of the recognised complications of pituitary surgery,18 either directly related to the intervention or secondary to the continued growth of the adenoma. Therefore, the possibility of a patient with adequate adrenal reserve in the early postoperative period later developing AI cannot be ruled out. In all cases, patient education about signs and symptoms of AI is necessary, along with subsequent follow-up.

The main strength of the study was that it included all the patients operated on in our hospital over a relatively long period of time, reflecting the population we work with on a day-to-day basis. Nevertheless, the study has several limitations. The low incidence of AI in our sample made it impossible to assess predictive factors associated with the development of this complication. We also lacked a control group with no administration of glucocorticoids, which would have made it possible to assess symptoms of AI.

In conclusion, the incidence of postoperative AI in our centre is 4.7%. Development of this complication can be predicted by serum cortisol levels on day three after surgery <4.1 μg/dl, with a sensitivity of 95.1% and a specificity of 100%. Levels <4.1 μg/dl require treatment with GC, although in half of the cases it can later be discontinued.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank all the members of the Multidisciplinary Committee for Hypothalamic Pituitary Pathology of the Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra, made up of the Endocrinology and Nutrition, Neurosurgery, Pathology, Radiodiagnosis and Radiation Oncology Departments, for following up and treating the patients included in this study throughout this time.

Please cite this article as: Irigaray Echarri A, Ollero García-Agulló MD, Iriarte Beroiz A, García Mouriz M, Zazpe Cenoz I, Laguna Muro S, et al. Evaluación de protocolo de manejo periquirúrgico con glucocorticoides tras cirugía hipofisaria. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2022;69:338–344.