Lipoprotein a is considered an independent factor of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease with high prevalence, but the availability of real and updated data in Spain as well as determination protocols are limited.

Main objectiveAnalyze the current state of the pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical process of Lp (a) and assess the relationship with other variables.

Material and methodRetrospective, observational, multicenter, anonymized study carried out in 2022 by survey of clinical laboratories.

Results21,926 determinations were obtained corresponding to 49 Laboratories. The values obtained were: Lp(a)>30 mg/dL = 46.87%, Lp(a)>50 mg/dL) 35.31%, Lp(a) >70 mg/dl = 26.8% Lp(a) >90 mg/dl = 19.3% with predominance of superiority in female gender in all established cut-off points.

Almost 30% of primary care doctors do not have access to their application. 56.9% do not have a rejection criterion. 70.6% do not have protocols for its determination.

There are two predominant analytical techniques, Immunophelometry (40%) and immunoturbidimetry (60%), 24% use nmon/L, 68% mg/dL and 8% report both.

ConclusionsThere is a low number of patients who have Lp(a) measured and of them the percentage of patients according to risk cut-off points are higher than those described. There is a lack of uniformity in pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical processes in which it is necessary to work in a multidisciplinary manner to avoid future cardiovascular events.

La lipoproteína (a) (Lp(a)) es considerada como un factor independiente de enfermedad cardiovascular arteriosclerótica con alta prevalencia, pero la disponibilidad de datos reales y actualizados en España así como protocolos de determinación en son limitados.

Objetivo principalAnalizar el estado actual del proceso preanalítico, analítico y post analítico de Lp (a) y valorar la relación con otras variables.

Material y métodoEstudio retrospectivo, observacional, multicéntrico, anonimizado realizado en el año 2022 realizado por encuesta a Laboratorios clínicos.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron 21.926 determinaciones correspondientes a 49 Laboratorios. Los valores obtenidos fueron: Lp(a)>30 mg/dL = 46,87%, Lp(a) > 50 mg/dL) 35,31%, Lp(a) >70 mg/dl = 26.8% Lp(a) >90 mg/dl = 19.3% con predominio de superioridad en genero femenino en todos los puntos de corte establecidos.

Casi el 30% de los médicos de atencion primaria no tienen acceso a su solicitud. El 56.9% no disponen de criterio de rechazo. El 70.6% no disponen de protocolos para su determinación.

Existen 2 técnicas analíticas predominantes, la Inmunonefelometria (40%) y la inmunoturbidimetría ( 60%, El 24% utiliza nmon/L, 68% mg/dL y un 8% informa ambas.

ConclusionesExiste un bajo numero de pacientes que presenta medición de Lp(a) y de ellos el porcentaje de pacientes según puntos de corte de riesgo son mas elevados que los descritos. Existe falta de uniformidad en proceso pre-analiticos, analítico y pos-analítico en los que hay que trabajar de forma multidisciplinar para evitar futuros eventos cardiovasculares.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) continue to be one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in Spain, despite the broad-based health care strategies designed to promote prevention and compliance with therapeutic objectives.1

Large-scale clinical trials continue to show that lowering LDL cholesterol (LDL-c) decreases atherosclerosis progression, cardiovascular risk, and even the size and composition of atheromatous plaque.2,3 However, despite the fact that we currently have a wide arsenal of lipid-lowering pharmacological treatments and innovative strategies with strict control of classic risk factors, the risk of suffering an episode of early and recurrent atherosclerotic vascular disease (AVD) remains high,4 even when LDL-C cholesterol levels are at targets of the patient's estimated risk. For this reason, it is necessary to integrate other independent risk factors into global cardiovascular risk assessment (CVRA) that can be reclassified into higher-risk subgroups, such as lipoprotein a (Lp(a)).

The structure of Lp(a) is similar to LDL in terms of its size, lipid composition, and presence of the apolipoprotein B-100 (apo B-100). The main structural difference between the two is that Lp(a) has a second, highly glycosylated and polymorphic protein called small apolipoprotein (a) (apo(a)), which binds to apolipoprotein B-100 by means of a disulphide bridge5 in equimolar proportion and are the main components involved in the pathogenic mechanisms of Lp(a).6,7 It has a lipid nucleus composed of approximately 45% cholesterol5 (Fig. 1).

It is the lipoprotein that transports the largest amount of oxidised phospholipids that induce inflammation of the arterial wall, secreting proinflammatory cytokines and giving rise to atherogenesis.8 Due to its hydrophilic nature, it is taken up by the foam cells of the arterial wall, favouring the retention and selective accumulation of Lp(a) in atherosclerotic lesions, thus developing altered endothelial function. Although, in equimolar terms, Lp(a) is more atherogenic than LDL, the additional component of small apo(a) may exacerbate atherothrombosis by promoting vascular inflammation. Its possible antifibrinolytic activity is associated with plasminogen inhibition, due to its structural similarity.9,10

This is therefore considered an independent risk factor with a marked genetic component, causing AVD and aortic valve calcifications.11 Lp(a) binds to the valvular endothelium by apo(a) and is incorporated into the valve cells where oxidised phospholipids demonstrate their proinflammatory activity, as well as direct bone formation through the differentiation of vascular cells into osteoblasts that contribute to valve calcification.12

All these characteristics make Lp(a) represent a widespread health problem in the world population. Data from population-based studies show that 10–30% of the world's population has Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl, which would correspond to 1.43 billion people affected worldwide, of which 148 million correspond to the European population.13 Its prevalence varies according to ancestry, affecting one in 5 Europeans,14–16 and exhibiting wide inter-individual variation across the general population, ranging from < 1 to > 1000 mg/dl.17 The plasma concentration of Lp(a) remains relatively constant throughout life in men, while in women it tends to increase with age after menopause, reaching maximum levels during the peri- and late post-menopause.18 There are also variations according to race. Nevertheless, results from the MESA, ARIC, and INTERHEART study showed very similar relationships between Lp(a) concentration and AVD risk in white, African American, and South Asian individuals.19–21

The concentration of Lp(a) is under strict genetic control more than any other lipoprotein. It has a heritability rate between 75 and 95%, and is predominantly determined by single-nucleotide variants in the LPA gene and copy number variants, specifically in the Kringle IV DOMAIN type 2.22,23 Due to the complexity of its molecular structure and diversity of size of the apo(a), there is significant controversy regarding the lack of standardisation in the analytical procedure. Lp(a) particles with a higher number of KIV-2 repeats are larger and heavier, providing lower concentration, however their measurement may be artifacted if tests that are not independent of the isoform are used, since the concentration could be underestimated or overestimated if a standardised calibrator is not used.24,25 Several scientific societies (Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratory [NLMDRL)] and the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine [IFCC])26 are currently working on the manufacture of calibrators in molar units, traceable to references verified by new methods such as mass spectrometry.27

There is currently a boom in research in relation to its pathophysiology, consensus documents, recommendations for clinical practice and clinical trials that will assess the possible existence of a reduction in events with new therapeutic targets,28,29 however the availability of data in Spain on the actual prevalence and measurement protocols is limited. Knowledge of the current status of protocols, analytical techniques and available values of Lp(a) analysed in different clinical laboratories in Spain can be used to design new health care strategies in cardiovascular prevention, proving this to be a cost-effective biochemical parameter.

Main objectiveTo analyse the current state of the pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical process of Lp(a) in different Spanish clinical laboratories, as well as assessing the relationship between the concentration of Lp(a) and other variables such as age, sex, and other lipid parameters.

Material and methodsA retrospective, observational, multicentre, anonymised study run in 2023, that required the completion of an electronic survey of different Spanish laboratories from 1st January 2022 to 31st January the same year, and consultation of the laboratory computer system (SIL in its Spanish acronym) of additional parameters included in the basic lipid profile.

The study received a favourable opinion from the Ethics Committee of the Virgen del Rocío and Virgen Macarena hospitals in Seville. The patients’ express informed consent was not required since this was an anonymised retrospective study through consultation of the SIL system.

To estimate the sample size, cluster sampling was designed with the Grandaria Mostral GRANMO calculator, guaranteeing an accuracy of 0.05, a population estimate of 0.23% and a confidence interval of 18–28%.

Inclusion criteria required minimum annual processing of 100 measurements, complete completion of the survey and consultation of the SIL with the inclusion of the following variables: Lp(a) + sex, age, requesting unit, and/or direct or calculated LDL-C, and/or Apo B and/or non-HDL cholesterol and/or triglycerides and/or HDL. Subsequently, a database was developed with all the results obtained to establish the relationship between Lp(a) and other analytical parameters included in the survey.

ResultsA total of 23% of the laboratories invited to collaborate in the study did not meet the inclusion criteria because they did not reach the minimum number of measurements or did not respond to the survey. The total number of Lp(a) measurements reported in the study for the year 2022, out of the 49 participating centres, was 21,926 and the graphical representation obtained for the frequencies, by sex, is shown in Fig. 2.

With respect to data obtained in the pre-analytical process, 82% of the data received corresponded to main hospitals, and 18% to regional centres. A total of 68.6% of the collaborating hospitals undertook measurement in their own laboratories, and 31.4% outsourced measurement, referring 15.7% to public centres of reference and 23.5% to private sample processing centres. Of the centres, 62.7% had a technique available in their portfolio of services available for request from primary care i.e. almost 30% of the aforementioned doctors did not have access to their request.

As regards the analytical process, there were 2 predominant analytical techniques, immunophelometry (40%) and immunoturbidimetry (60%). No centre reported that it processed the samples using ELISA (enzyme-linked immunoassay) techniques or mass spectrometry. As they had different analytical methodologies, and each supplier of reagents had a calibrator referenced or not to the IFCC SRM2B reference material, the percentage of units reported was diverse; 24% used nmon/l, 68% mg/dl and 8% reported both. The most common conversion factor applied was mg/dl = (nmol/l + 3.83) × 0.4587.

With regard to the procedure applied in different laboratories, as regards demand management included in the post-analysis process, the following results were obtained: in all, 41.2% applied the rejection criterion by inserting an explanatory comment: “This is only determined once in a lifetime with the exception of patients being treated with therapies directed against PCSK9″; 6% implemented a rejection criterion for primary care; and 56.9% did not have a rejection criterion, which was set whenever requested. With regard to intra-hospital organisation and multidisciplinary collaboration, 70.6% did not have any hospital protocols for this measurement, nor did they have any in their different health care areas.

Looking now at the use of external quality controls, only 38.3% had this control, mainly corresponding to the external quality assurance programme under the Spanish Society of Laboratory Medicine.

As regards the profiles prepared for the request of analytical tests to assess the degree of adherence to the consensus document on lipid profiles in Spanish clinical laboratories, only 12% had incorporated Lp(a) into the basic lipid profile in primary care and 26% in specialised care.

The clinical specialty requesting Lp(a) differs depending on the organisation of the hospital centre and the availability of lipid units. The percentages of applications by specialty corresponded 30.01% to cardiology, 19.45% to internal medicine, 16.24% to endocrinology, 5.10% to neurology and 2.69% to paediatrics.

In order to assess and compare different geographical areas, a visual representation of the number of Lp(a) tests was produced, according to geolocation in Spain (Fig. 3). The distribution of the values obtained taking cut-off points at 30, 50 and 180 mg/dl, by sex, is shown in Fig. 4, with a predominance of increased levels in women compared to men. When intermediate cut-off points such as Lp(a) > 70 mg/dl were included as sub-analyses, we found 26.8% of the data obtained (25.9% males and 28.7% females) and Lp(a) > 90 mg/dl 19.3% (18.1% males and 21.5% females), again with a predominance of the female gender.

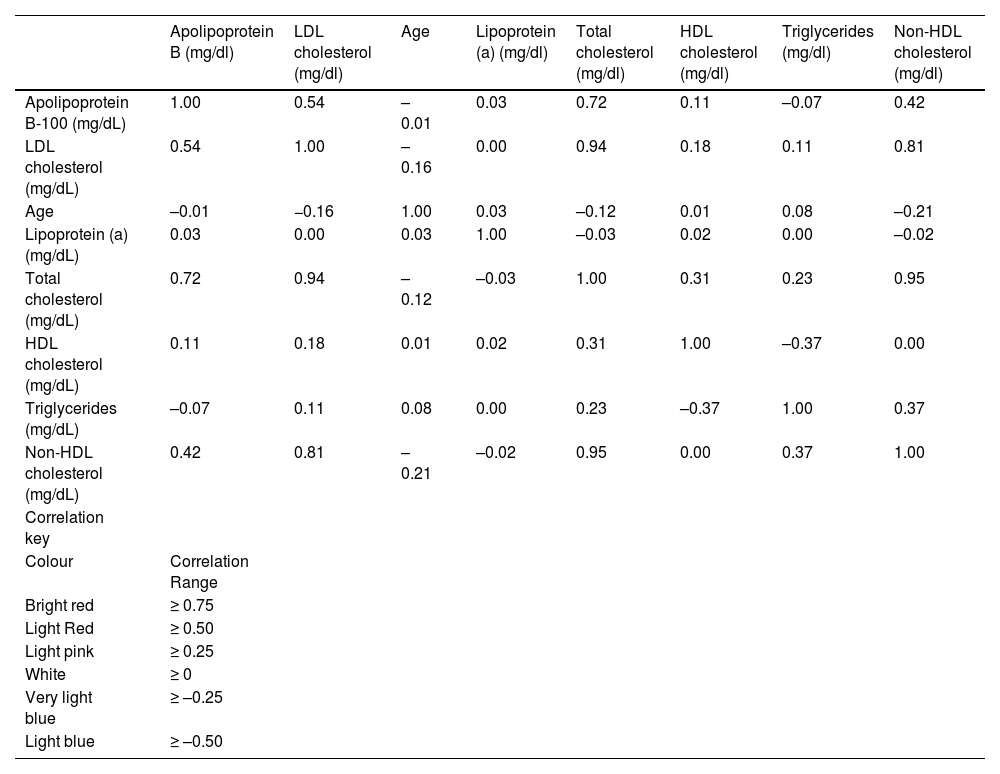

Fig. 5 shows graphically the percentage of patients with Lp(a) higher than 50 mg/dl, by hospital. Fig. 6 provides a graphic representation differentiated by sex and mean values of other lipid parameters included in the analysis, which corresponded to the value of associated Lp(a) in the SIL search. Finally, a heat map was constructed to assess the possible relationship of Lp(a) with other parameters, confirming its characterisation as an independent marker, as shown in Table 1.

Heat map showing Lp(a) as an independent marker of other additional analytical parameters.

| Apolipoprotein B (mg/dl) | LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | Age | Lipoprotein (a) (mg/dl) | Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | Triglycerides (mg/dl) | Non-HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein B-100 (mg/dL) | 1.00 | 0.54 | –0.01 | 0.03 | 0.72 | 0.11 | –0.07 | 0.42 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.54 | 1.00 | –0.16 | 0.00 | 0.94 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.81 |

| Age | –0.01 | −0.16 | 1.00 | 0.03 | –0.12 | 0.01 | 0.08 | –0.21 |

| Lipoprotein (a) (mg/dL) | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 1.00 | –0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | –0.02 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.72 | 0.94 | –0.12 | –0.03 | 1.00 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.95 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 1.00 | –0.37 | 0.00 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | –0.07 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.23 | –0.37 | 1.00 | 0.37 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.42 | 0.81 | –0.21 | –0.02 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 1.00 |

| Correlation key | ||||||||

| Colour | Correlation Range | |||||||

| Bright red | ≥ 0.75 | |||||||

| Light Red | ≥ 0.50 | |||||||

| Light pink | ≥ 0.25 | |||||||

| White | ≥ 0 | |||||||

| Very light blue | ≥ –0.25 | |||||||

| Light blue | ≥ –0.50 |

The design of the survey focussed on questioning the most representative points of interest, with a limited number of items to favour the degree of participation. Studies designed to obtain health outcomes through voluntary surveys of health care professionals have inherent limitations as regards the procedure and number, type and characteristics of the items to be included. About 23% of respondents did not complete the survey or did not meet the established inclusion criteria. It should be pointed out that the information reported from the 49 centres was not representative of the general population, rather data referring to the collaborating centres, so we could not refer to the prevalence of hyper Lp(a) across the board in Spain, taking the values obtained. This was because the results could present a bias of a higher number of patients in secondary prevention, in relation to sex or greater specialisation in lipidology in the participating centres.

The data obtained from the surveys included hospitals corresponding to all levels of care, highlighting several regional centres with recognised lipid units, extremely active in the characterisation of familial hypercholesterolaemia presented by a large number of tested patients, such as the Hospital de Andújar, in comparison with other hospitals located in large cities. More than 30% (31.4%) outsourced to their corresponding main hospitals (15.7%) or private laboratories (23.5%), which incurred an increase in transport costs, as well as an increase in costs in general, taking into account that there were reagents available for incorporation within large analytical chains for sample processing. This is a technique that does not require special pre-analytical conditions30; is performed on a serum or plasma sample; has great stability; moderate cost; and can be automated, so its implementation should be recommended in all laboratories. It was noteworthy that 18% of regional hospitals undertook their own testing and had their own self-analysers.

As regards availability of the technique of analysis in the portfolio of services, almost 30% of primary care physicians did not have access to their request, which made it difficult to characterise overall cardiovascular risk and run segregation studies. In the recent HER(a) study on the Spanish population, first-degree relatives of patients who had suffered an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and had an Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl were analysed. Of the relatives, 59.4% also had increased Lp(a) levels,31 so the family cascade study appeared to be cost-effective and ideal for proposal from primary care in cases of high risk of AVD. In the “Consensus document for the measurement and reporting of the lipid profile in Spanish clinical laboratories”,32 15 Spanish scientific societies agreed to include Lp(a) in the basic lipid profile of primary and specialised care and to determine this at least once in a lifetime. Nevertheless, only 12% of respondents had adhered to the recommendations of the consensus document. It is therefore necessary to insist on the dissemination and application of this document in order to improve the characterisation of global cardiovascular risk (CVR). In the primary prevention setting, elevated Lp(a) is associated with several AVD outcomes, as well as aortic valve stenosis and all-cause cardiovascular mortality. Kamstrup and Nordestgaard33 showed with biochemical and genetic studies that Lp(a) levels above the 75th percentile increased the risk of aortic valve stenosis and myocardial infarction, while higher levels (>90th percentile) were associated with an increased risk of heart failure. We should therefore insist on authorising the request to primary care, where we should not forget that patients at high or very high risk and even secondary prevention are screened.

It is noteworthy that 70.6% of hospitals did not present protocols for their request or when to request it without the consequent design of the corresponding care pathway. Regarding the ideal time to measure < this, the 2021 guidelines of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society,34 as well as the EAS 2022 consensus,35 are clear and recommend the measurement of Lp(a) at least once in a lifetime, as part of the initial screening of lipids to assess cardiovascular risk. It is doubtful whether or not quantification is appropriate at a time close to the event, however, although inflammatory conditions could cause a temporary variation in plasma levels, Lp(a) remains fairly constant throughout the individual's life and provides greater benefit from establishing the level before discharge. The results of a large-scale multicentre register in Germany on the prevalence of Lp(a) in cardiac rehabilitation patients showed that they had recorded levels for only 0.19% of patients undergoing aortic valve intervention; 4.96% with previous myocardial infarction < 60 years, and 2.36% in the case of current myocardial infarction < 60 years of age. Therefore, they conclude that it would be necessary to substantially increase awareness of Lp(a) to better identify and treat high-risk patients.36

More than 50% (56.95%) did not include demand management rules that apply a rejection criterion, so the reanalysis of Lp(a) was done whenever it was requested, which entailed unnecessary consumption of resources. The 41.2% who applied it also included an explanatory comment on the non-need for monitoring, with the exception of patients being treated with therapies for PCSK.9 Repetition could be considered in other cases such as a change in laboratory technique in patients in grey areas (30−50 mg/dl), hypothyroidism, menopause, nephrotic syndrome or confirmation of excessively increased concentrations. These points are key for the inclusion of an analysis in the portfolio of laboratory services. This should be the first step for the lipid units in the correct use and management of Lp(a) at the different levels of care.

In relation to the type of requestion physician, the results are very consistent with the clinical practice of care; the specialty of internal medicine (IM), due to the relationship between Lp(a) and familial hypercholesterolemia, and the specialty of cardiology, especially patients in secondary prevention, although they seem insufficient. Similarly, requests from neurology for the assessment of patients with stroke should be increased. Similar results were obtained in a study carried out at the Hospital de La Princesa (Madrid) in 2021–2022, coinciding with the study period, recording 48% of requests from IM, 46% from cardiology, endocrinology 2%, neurology 1% and other services 3%.37

The graphic distribution of frequencies of the data obtained corresponding to the 21,926 measurements was very similar to levels recently published in the consensus document on Lp(a) by the Italian Society for the Study of Atherosclerosis on 2 Italian populations with 1534 participants, corresponding to the Progressione Delle Lesioni Intimali Carotidee (PLIC) study.38 Likewise, this was similar to the corresponding data from the UK Biobank35 published in the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Statement for the year 2022. The concentration of Lp(a) is quite stable throughout adult life and slightly higher (5–10%) in women than in men.39 Pregnancy doubles Lp(a) concentrations, while there also is also a slight increase in Lp(a) in menopause.30 Our results are consistent with scientific evidence, obtaining a higher percentage of female patients with Lp(a) > 30, >50 and >180 mg/dl which, looking at the age of the female population, could be increased by hormonal influence.

The availability of data on the actual prevalence of Lp(a) in our country is limited; there are records from scientific societies, however not from large population studies. A previous study was carried out in 20 hospitals in Andalusia and 3 in Extremadura,40 corresponding to data from levels recorded in 2019 and 2020, also by a survey system, by expanding the number of participating laboratories and the geographical distribution from the previous study. This increased the percentage of patients with Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl from 29.5% to the current 35.21% and Lp(a) > 180 mg from 1.52% to the current 4.87.

In 2012, in a study carried out on the island of Gran Canaria, with 1030 patients, analysing the relationship between Lp(a) and diabetes, 86.2% of patients had Lp(a) < 46 mg/dl, the cut-off point adopted in the study to assess the possible relationship between high levels of lipoprotein(a) and its association with a lower prevalence of diabetes as age progresses.41 In our study, this association was not assessed, as glycosylated haemoglobin parameters were lacking in the survey. Concurrently with our study, another study corresponding to the Hospital de La Princesa in Madrid,37 27.2% recorded Lp(a) > 50 and 1.9% Lp(a) > 180 mg/dl. In a German register,36 very similar figures were obtained; the levels of Lp(a) registered were > 50 mg/dl in 28.79% for aortic valve intervention, 29.90% for current myocardial infarction < 60 years and 36.48% for previous myocardial infarction < 60 years, compared to 24.25% (control.

Focussing on the analytical process, the analytical techniques for processing samples were mainly immunoturbidimetric(60%), which is a method whose measurement is directed against small molecules and gives us the molar concentration. This is the case, to a lesser extent, in immunonephelometry, where the total mass of the molecule measured (proteins, lipids and carbohydrates and is a method sensitive to isoforms) highlighting that most of this equipment -nephelometers- is not integrated within analytical chains. Both techniques use latex particles coated with anti-Lp(a) antibodies, which react with Lp(a) from the patient, form a precipitate, and the degree of light scattering is measured with a detector. Depending on the angle of measurement, one technique or the other is used. The analytical variability depends not only on the type of technique but also on the reference material which the calibrators from the different suppliers are produced. The calibrator recommended by the IFCC is the one relating to the material set by ELISA SRM2B. This will soon be updated by a mass spectrometric measuring system. As different analytical methodologies are available, and each company has a calibrator relating or not to the IFCC SRM2B reference material, there is a diversity of units in the analytical reports, as described in the results. The percentage of units reported is 24% nmon/l, 68% mg/dl and 8% report both. This makes it difficult to compare results and monitor the patient when running the test in different laboratories, since the conversion of units is not recommended, as the measurement to be quantified is different: mass or molar concentration. The use of external quality controls is very scarce, less than 40% (38.3%). These controls enable the quality of the results issued with the self-analysers to be checked and an inter-comparison with other centres attached to the quality assurance programme should be made, so this should be purchased in the laboratories to minimise any metrological biases that may exist.

Methods that measure the molar concentration of Lp(a) measure the particle concentration of the principal component that identifies the Lp(a) particle, which is apo(a), without the bias introduced by the particle size. In contrast, mass assays measure varying amounts of all components of the Lp(a) mass, including sensitivity to differences in the size of the apo(a) isoform.42 Therefore, mass assays, which provide results in mg/dl, have an inherent limitation as regards accurate assessment of the concentration of circulating particles of Lp(a) and may not provide adequate analytical quality in measurement, from a clinical point of view.42 Since the mass of Lp(a) particles is variable, direct conversion can only be an approximation. Ideally, Lp(a) should be measured in molar units, as this ensures that each Lp(a) particle is only recognised once. However, this is difficult to achieve when polyclonal antibodies are used in assays, as these antibodies probably recognise the K-IV repeating domain of apo(a).40 This leads to an overestimation of Lp(a) values in samples with Lp(a)molecules larger than those of the calibrator and an underestimation of Lp(a) values in samples with Lp(a) molecules smaller than those of the calibrator. It is important to clarify that the assays that provide the results in mg/dl, indicate the mass of the particles of different sizes, while those that indicate nmol/l, refer to the actual number of particles.

In the SIL search, we analysed other additional concurrent parameters in the analyses consulted. Table 1 shows the construction of a heat map, to establish if there is any relationship between Lp(a) and other concomitant parameters studied in the lipid profile. The results showed that Lp(a) was a risk factor that was independent of the other lipid parameters analysed, as demonstrated by its association with familial hypercholesterolemia.43 The mean concentrations obtained from the different parameters that made up the basic lipid profile, as shown in Fig. 6, could be positioned in normal intervals if we consider the cohort of patients evaluated as low risk but with a more proatherogenic profile, if we assess this in a context of secondary prevention in both LDL-C, apo B-100, and the residual cardiovascular risk that hypertriglyceridemia may pose. This is one of the main limitations of the study, in which the data provided by the SIL does not make it possible to differentiate the type of diagnosis or risk for the patient.

Fig. 3 shows the geolocated Lp(a) data obtained in relation to the number and concentration of Lp(a), but there are no clusters of higher aggregation, confirming again, with respect to the previous study, that several Andalusian centres consolidated higher concentrations, as well as a greater number of patients tested.

On the map of hospitals (Fig. 5) with concentrations of Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl, the differences obtained should not be interpreted as a higher or lower prevalence in these cities, since in 2022 the analysis in primary care was quite limited. Rather, this is an assessment of a larger number of patients safely tested in secondary prevention or hospitals with long-standing lipid units in the study of hypercholesterolemia, where the determination of Lp(a) was part of the biochemical profile indicated in these patients, due to its potential relationship, as indicated in the SAFEHEART study.44

In conclusion, according to the data obtained, the number of patients with recorded levels for Lp(a) in Spain, according to this survey, is low and with an Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl slightly higher than the available results. It is thus necessary to implement the available consensuses and undertake a much-needed harmonisation of the analytical method with a new reference calibrator, assessed by an isoform-insensitive method such as mass spectrometry, as well as introducing protocols and clearly defined multidisciplinary care pathways, including primary care for effective control of this independent cardiovascular risk factor.

FundingThis work was funded by a collaboration agreement between Novartis and the Jose Luis Castaño Foundation within the Spanish Society of Laboratory Medicine.

To the management staff of the Jose Luis Castaño Foundation within the Spanish Society of Laboratory Medicine and fellow collaborators in the Batary project working group.

Pilar Calmarza (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza), Irene González Martin (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre), Jose Puzo Foncillas (Servicio de Análisis Clínicos y Bioquímica Clínica, Hospital Universitario San Jorge de Huesca), Núria Amigó Grau (Deparment of Basic Medical Science, Reus, Tarragona), Baatriz Candas Estébanez (Laboratorio Clínico Hospital de Barcelona), David Ceacero Marín (Laboratorio de Análisis Clínicos, Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge), María Martín Palencia (Servicio Análisis Clínicos, Hospital Universitario de Burgos), Carlos Romero Román (Hospital General Universitario de Albacete), Teresa Contreras Sanfeliciano (Laboratorio Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca), Antonio Fernández Suarez (Laboratorio Alto Guadalquivir, Andújar, Jaén), Emilio Flores Pardo (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario de San Juan, San Juan de Alicante, Alicante), Alejandra Fernández Fernández (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias), Cristina Gómez Cobo (Laboratorio Hospital Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca, Illes Balears), Lidya Esther Ruiz García (Laboratorio Hospital Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), Marta Duque Alcorta (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid), Beatriz Zabalza Ollo (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario de Navarra, Navarra), Marta M. Riaño Ruiz (Laboratorio Complejo Universitario Insular Materno Infantil de Gran Canaria), María Jesús Cuesta Rodríguez (Laboratorio Complejo Universitario Insular Materno-Infantil de Gran Canaria), Carlos Tapia Artiles (Laboratorio Complejo Universitario Insular Materno-Infantil de Gran Canaria), Firma Isabel Rodríguez Sánchez (Laboratorio de Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas, Almería), Enrique Prada de Medio (Laboratorio Hospital Virgen de la Luz, Cuenca), Blanca M. Nieves Fernández Fatou (Laboratorio Hospital Juan Ramon Jiménez de Huelva), María Dolores Badía Carnicero (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario de Burgos), Elena Fernández Vizan (Laboratorio Hospital V. de la Concha, Complejo Asistencial de Zamora), Guillermo Boyero García (Laboratorio Hospital V. de la Concha, Complejo Asistencial de Zamora), María del Pilar Álvarez Sastre (Laboratorio Hospital V. de la Concha, Complejo Asistencial de Zamora), Ana Belén García Ruano (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario de Jaén), Joaquín Bobillo Lobato (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme), María del Mar Viloria Peñas (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme), Carmen Ortiz García (Laboratorio Virgen de la Victoria de Málaga), Sonia Blanco Martín (Laboratorio Virgen de la Victoria de Málaga), Andrés Cobos Díaz (Laboratorio Virgen de la Victoria de Málaga), Mónica Ramos Álvarez (Laboratorio Hospital Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza), José Ruiz Budría (Laboratorio Hospital Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza), Laura Sahuquillo Frías (Laboratorio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia), Goizane Marcaida Benito (Laboratorio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia), Ana Cosmen Sánchez (Laboratorio Hospital Santa Barbara), Ainhoa Belaustegui Foronda (Laboratorio Hospital de Cruces Bizkaia), Carmen de Ne Lengaran (Laboratorio Hospital de Txagorritxu, Bizkaia), María Dolores Badía Carnicero (Laboratorio Hospital de Valdecilla, Santander, Cantabria), María Martín Palencia (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario de Burgos), Simón Gómez-Biedma Gutiérrez (Laboratorio Hospital General de Almansa), Jose Zarauz García (Laboratorio Hospital Rafael Méndez, Lorca, Murcia), Juan Cuadros Muñoz (Laboratorio Análisis Clínicos Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar de Cádiz), Mercedes Calero Ruiz (Laboratorio Análisis Clínicos Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar de Cádiz), Ana Sáez-Benito Godino (Laboratorio Análisis Clínicos Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar de Cádiz), María Esteso Perona (Laboratorio Hospital de Villarrobledo), Fernando Rodríguez Cantalejo (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofia de Córdoba), María Muñoz Calero (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofia de Córdoba), Luis Calbo Caballos (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario de Jerez, Cádiz), Esther Fernández Grande (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario de Jerez, Cádiz), Adrián Fontán Abad (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario San Pedro, Logroño, La Rioja), Ana Belen Lasierra Monclus (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario San Jorge, Huesca), Naira Rico Santana (Laboratorio Hospital Clínic de Barcelona), Maria del Mar del Aguila (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves), Raquel Barquero Jiménez (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid), Alberto Redruello Alonso (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid), Isabel García Calcerrada (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario Santa Bárbara de Soria), Alicia de Lózar de la Viña (Laboratorio Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria, Gran Carnaria), Nuria Alonso Castillejos (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid), Patricia Ramos Mayordomo (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid), Rosa María Lobo Valentín (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid), Alberto Cojo Espinilla (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario de Donostia), Virginia Tadeo Garisto (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario la Fe, Valencia), María Simó Castelló (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario la Fe, Valencia), Cristina Aguado Codina (Laboratorio Hospital Universitario La Fe, Valencia), Clara Peña Cañaveras (Laboratorio CLILABdiagnostic, Hospital Vithas), Vicente Aguadero Acera (Laboratorio CLILABdiagnostic Hospital vithas), Carmen Tejedor Mardomingo (Laboratorio CLILABdiagnostic, Hospital Vithas, Sevilla) y Cristobal Morales Portillo (Hospital Vithas, Sevilla).