New horizons in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia

More infoAtherosclerosis is a chronic disease that begins in early childhood, and without intervention, progresses throughout life, and inevitably worsens over time, sometimes rapidly. LDL cholesterol, beyond being a cardiovascular risk factor, is a causal agent of atherosclerosis. Without LDL cholesterol there is no atherosclerosis, so the evolution of the disease is modifiable, and even reversible.

La aterosclerosis es una enfermedad crónica que comienza en la primera infancia, y sin intervención, progresa a lo largo de la vida, e inevitablemente empeora con el tiempo, en ocasiones de forma acelerada. El colesterol LDL, más allá de ser un factor de riesgo cardiovascular, es agente causal de la aterosclerosis. Sin colesterol LDL no hay aterosclerosis, por lo que la evolución de la enfermedad es modificable, e incluso reversible.

About 5 decades ago, the upper range of cholesterol considered "normal", conveyed by low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) in Western countries was much higher than today, since it was based on epidemiological data, and not on any biological aspects. In addition, as in the case of other cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, high blood pressure or diabetes mellitus, the fact that not only the concentration of LDL-C is taken into account but also the cumulative exposure time, assists in optimising current treatment strategies. Moreover, we must consider that the delay in initiating hypocholesterolaemic treatment will, a priori, continue to expose people to avoidable risk.1

Next, we shall explore the most important data on the evolutionary development of LDL-C lowering drugs, as well as those aspects most closely linked to cholesterol metabolism, to then delve into the key role of LDL-C in atherosclerosis and conclude with the evidence that supports the safety and cardiovascular benefits of clinical situations that are accompanied by low LDL-C concentrations.

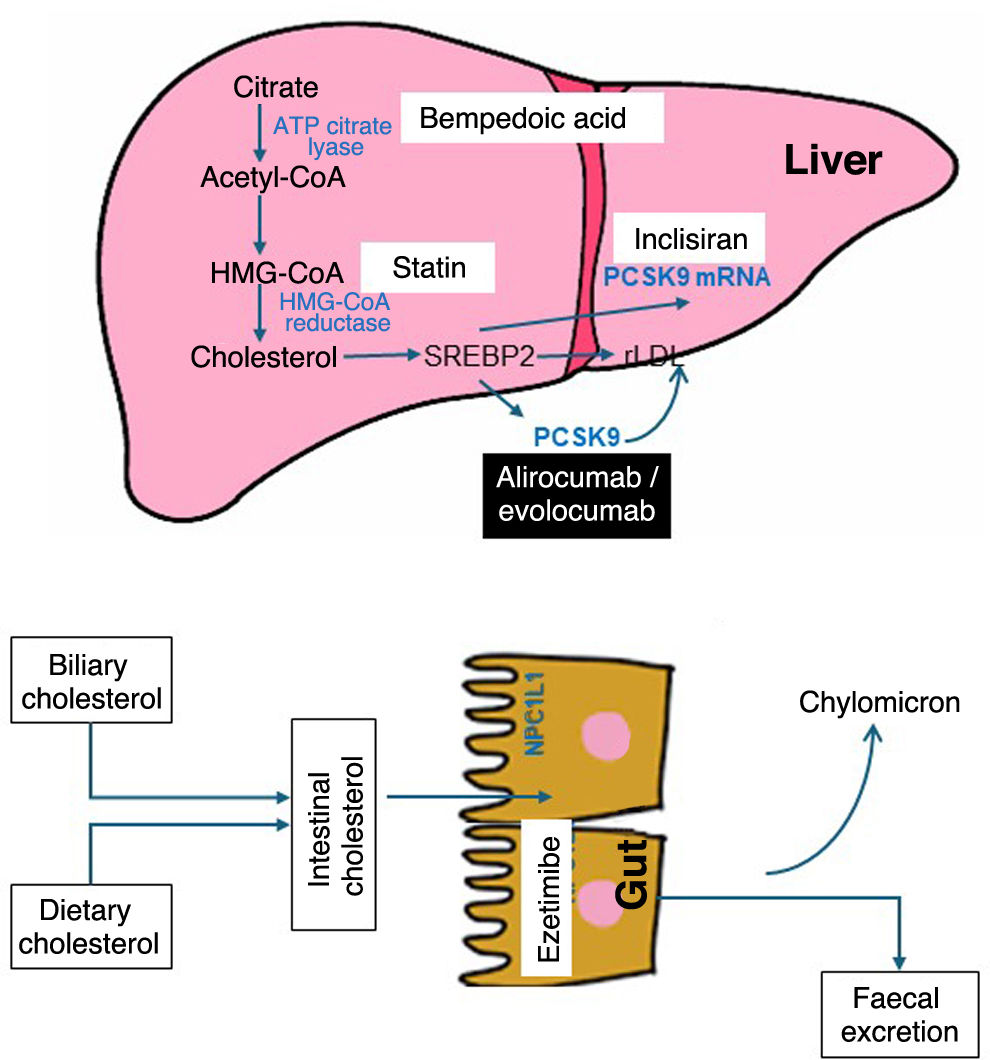

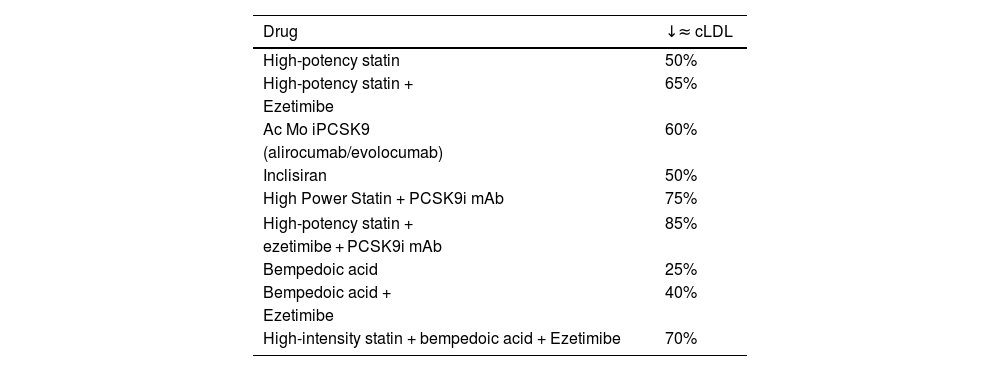

Evolution of lipid-lowering agents: from statins to the present timeThe mechanisms of action and the effect on LDL-C concentration of the principal drugs are detailed in Fig. 1 and Table 1, respectively. Leaving aside age-old drugs, such as fibrates, niacin and resins, the introduction in 1987 of the first statin, lovastatin, marked a milestone in cardiovascular medicine by achieving a reduction in LDL-C of close to 40% at its maximum dose. Subsequently, atorvastatin and rosuvastatin extended this reduction to 50%. Possible questions about the impact and safety of lowering LDL-C were largely dispelled in 1994 with the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S),2 revealing a 30% drop in total mortality for the first time. This result was corroborated by the Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID)3 and Heart Protection Study (HPS).4 Likewise, Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (PROVE-IT)5 and Treating to New Targets (TNT)6 concluded that higher versus lower potency statins were associated with greater cardiovascular benefits. Since then, statins have been the most widely used drugs, having confirmed their efficacy in the prevention of CVD for all age groups and vascular risk levels.7–10 At this point, it should be noted that the reduction in cardiovascular risk with statins is the result of the absolute reduction in LDL-C, so that a decrease of 40 mg/dl is accompanied by a 22% reduction in risk.

Mean reduction in LDL-C with currently available lipid-lowering drugs.

| Drug | ↓≈ cLDL |

|---|---|

| High-potency statin | 50% |

| High-potency statin + | 65% |

| Ezetimibe | |

| Ac Mo iPCSK9 | 60% |

| (alirocumab/evolocumab) | |

| Inclisiran | 50% |

| High Power Statin + PCSK9i mAb | 75% |

| High-potency statin + | 85% |

| ezetimibe + PCSK9i mAb | |

| Bempedoic acid | 25% |

| Bempedoic acid + | 40% |

| Ezetimibe | |

| High-intensity statin + bempedoic acid + Ezetimibe | 70% |

PCSK9i mAb: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 monoclonal antibody inhibitor; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Other treatment options apart from statins, such as ezetimibe, the selective inhibitor of the intestinal cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1 like 1 (NPC1L1), introduced in 2001, reduced LDL-C by an additional 21% when combined with a statin. Since 2015, the inclusion of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors in the treatment arsenal has made it possible to achieve plasma concentrations of LDL-C below 40 mg/dl. The respective clinical studies with these drugs, IMPROVE-IT,11 FOURIER12 and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES,13 showed an incremental reduction in non-fatal cardiovascular events, consistent with their lipid-lowering effects and duration of treatment, also with the same decrease in risk per unit of reduced LDL-C as statins.14 Moreover, taken together, these studies have provided 2 new lessons that should be highlighted: the safety profile in this clinical context, with very low serum concentrations of LDL-C, and the fact that this is the only biological parameter that does not have a lower threshold beyond which no cardiovascular benefits are obtained. In fact, the 2019 European clinical guideline for the control of dyslipidemia15 suggests an LDL-C level <40 mg/dl as a treatment target in patients who have had more than one serious cardiovascular event.

In 2020, the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency tendered a new oral lipid-lowering agent, bempedoic acid, which inhibits cholesterol biosynthesis by blocking adenosine triphosphate-citrate lyase (ACL), at an earlier metabolic stage than statins, and whose result is a 25% reduction in LDL-C in monotherapy and 40% associated with ezetimibe. In the CLEAR-Outcomes study,16 after a median follow-up of 40.6 months in statin-intolerant patients, treatment with bempedoic acid 180 mg/day was associated with a significant 13% decrease in the risk of cardiovascular events.

Finally, and more recently available is inclisiran, a double-stranded small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA), in which the sense strand is conjugated to a triantennary N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) complex to facilitate its uptake by hepatocytes, where it deploys the RNA interference mechanism and the catalytic cleavage of PCSK9 mRNA. Efficacy studies have corroborated that with a biannual administration (after an initial dose and another at 3 months) subcutaneously, an average reduction of 50% in LDL-C levels is achieved. Currently, there are 3 ongoing clinical studies with inclisiran to demonstrate its potential cardiovascular benefits.17

Cholesterol metabolismCholesterol is an essential molecule for modulating the fluidity of cell membranes, the functioning of cell transporters and intracellular signalling systems; it is also a precursor of myelin, bile salts, vitamin D, steroid hormones and plays a key role in maintaining skin impermeability. All somatic cells, including astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, synthesize cholesterol through the same pathway used by the liver, even when the plasma concentration of LDL-C is low; in addition, these cells can obtain small amounts of cholesterol from high-density lipoproteins (HDL). In fact, no tissue depends on the transfer of cholesterol from LDL.18

With regard to its catabolism, the human body is unable to metabolise cholesterol because it is unable to break its central skeleton, constituted by the cyclopentaneperhydrophenanthrene ring, a fact that highlights the importance of cholesterol homeostasis through the balance between endogenous synthesis, intestinal absorption and excretion of bile acids. All this justifies the interest in the mechanisms of intracellular synthesis and intestinal absorption of cholesterol as treatment targets to reduce cholesterolaemia (Fig. 1).

Hypercholesterolemia, at the expense of the LDL fraction, and its consequent accumulation in tissues such as the sclera, dermis and tendons but mainly in the arterial wall, can lead to complications. In this sense, CVD, especially coronary heart disease and atherothrombotic ischemic stroke, are the leading cause of mortality in the world and one of the main factors in disability.19

LDL as an etiological agent of arteriosclerosisVery low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) are synthesised in the liver and released into the bloodstream to transport triglycerides and fat-soluble vitamins to the tissues; They also contain sterified cholesterol that stabilises them. Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) releases fatty acids from chylomicron triglycerides and VLDLs, converting the latter into intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDLs) and subsequently LDL. Therefore, LDL particles are essentially a byproduct, and their removal from the circulation is achieved primarily through LDL receptors on the surface of hepatocytes, which bind to the apolipoprotein (apo)B of the LDL particle. Because LDL has no essential function other than to recycle cholesterol back to the liver, very low plasma LDL-C is compatible with health, as long as the other components of the lipidome are within the normal range.

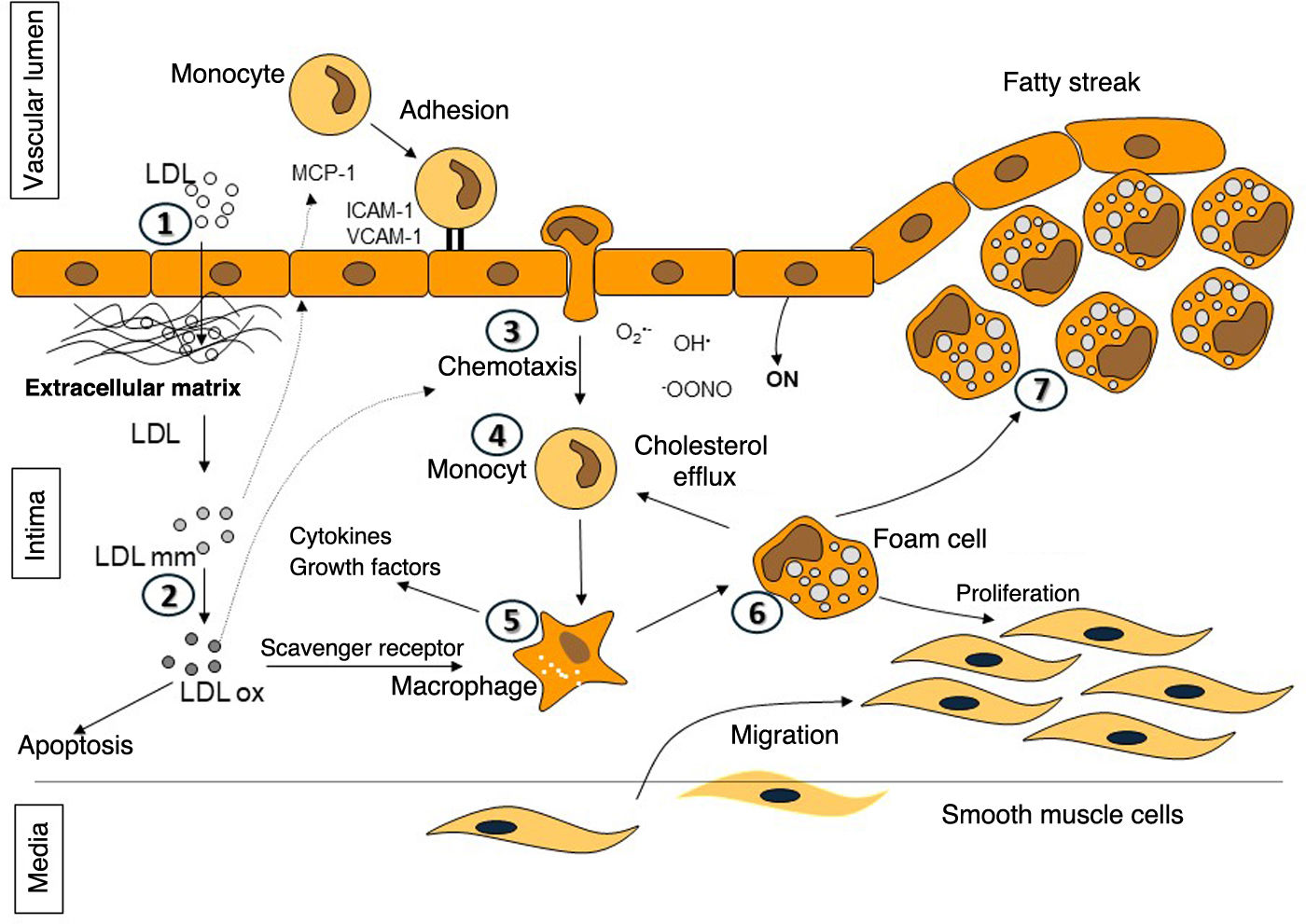

Although there are still enigmas to be solved in atherogenesis, its pathophysiology has been widely studied, concluding that LDL-C is a vascular toxicant (Fig. 2).20,21 The central process underlying the onset and progression of atheromatous plaque is the entry and retention of LDL into the subendothelial space. Normally, most of the LDL particles that cross the endothelium and enter the intima usually go back into the circulation; however, in the presence of certain cardiovascular risk factors or impaired laminar flow, the probability of LDL particles adhering to the proteoglycans of the intima and being retained in situ increases, leading to progressive accumulation over time in the arterial wall.22 These retained LDL particles are phagocytosed by macrophages, becoming foam cells. Finally, the chronic release of cytokines and other inflammatory and thrombotic mediators leads to maladaptive inflammation, apoptosis, and activation of prothrombotic pathways.20,21

Stages in atheroma plaque formation. 1-2: entry of low-density lipoproteins (LDL) into the subendothelial space and subsequent modification; 3-5: release of growth factors and cytokines that promote diapedesis of monocytes into the intima and their differentiation into macrophages; 6: formation of foam cells due to internalisation of modified and oxidised LDL; and 7: establishment of the fatty streak by accumulation of foam cells.

Beyond LDL, other apoB-containing lipoproteins up to 70 nm in diameter, including IDLs, smaller VLDLs, chylomicron remnants, and lipoprotein(a) also cross the endothelium and penetrate the arterial intima. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins may have difficulty leaving the intima due to their larger size or become trapped by components of the intima.22 While LDL requires changes in order to be absorbed by macrophages, the remaining particles are taken up by members of the LDL receptor family in their native state. In addition, hydrolysis of triglycerides by LPL from the remaining particles increases the inflammatory response of macrophages.21

In general, this entire process occurs over decades, so different "stages" can be differentiated in atherosclerosis (Fig. 1).23,24 It is therefore easy to understand that this is a chronic disease that begins in early childhood and without intervention, progresses throughout life and inevitably worsens over time, sometimes in an accelerated manner. In late adolescence, the prevalence of reversible atherosclerotic lesions (American Heart Association class 1–3) is directly related to conventional cardiovascular risk factors; by the age of 30–35 years, advanced lesions (American Heart Association class 4–5) develop in the same places and have a similar relationship with risk.25 The pace and degree to which this occurs varies between individuals, however the progression is undoubtedly age-related. Larger complex plaques can rupture or erode and initiate intraluminal vessel thrombosis, occlusion, and subsequent internal organ infarction.26 Therefore, the fundamental pathological process underlying a cardiovascular event is the development of high-risk atherosclerotic plaque. Consequently, early diagnosis and intensive treatment of atherosclerosis may be the best strategy to eliminate cardiovascular risk.

The sustained impact of elevated LDL-C on the progression of atherosclerotic disease is exemplified in individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia, who, being exposed from birth to very high concentrations of LDL-C, present cardiovascular complications before the age of 15 years in the homozygous form, and in young adulthood in the heterozygous form, if they do not receive lipid-lowering pharmacological treatment. On the other hand, modern regression studies with intravascular ultrasound, applying novel image analysis techniques, have shown that the achievement of low LDL-C levels, thanks to the combined therapy of statins and PCSK9 inhibitors, is accompanied by beneficial effects on plaque composition together with a decrease in atherosclerotic burden.27 Consequently, against this clinical backdrop we are embarking upon etiological treatment of the disease.

Low LDL-C: science or fictionThe safety of low or very low plasma concentrations of LDL-C is supported by the evidence of different clinical situations that we will discuss below.

It is known that LDL-C levels are much lower in newborns than in children or adults. Khoury et al.28 described the mean LDL-C in 122 cord blood samples as 23 ± 10 mg/dL. Similarly, a national study with a larger sample size showed a concentration of 35 mg/dl.29

In addition to this irrefutable physiological testimony, it should be emphasised that our ancestors, belonging to primitive hunter-gatherer societies, while still following their indigenous lifestyle, did not develop signs of atherosclerosis, even in those who lived to the seventh and eighth decades of life. These populations had cholesterolaemia between 100 and 150 mg/dL with estimated LDL-C levels of 50–75 mg/dL.30

On the other hand, there are genetic mutations that occur with low LDL-C concentrations, and almost all of them are associated with a lower risk of CVD.20 Therefore, inheriting an LDL-C lowering allele in one of these genes is analogous to being randomly assigned to LDL-C lowering therapy. There is a linear dose-dependent relationship between the absolute amount of lifetime exposure to low LDL-C and the corresponding vascular risk. This relationship is similar to that between the absolute reduction in LDL-C and the proportional reduction in cardiovascular events observed in pharmacological intervention trials. However, the slope of these relationships is much steeper for lifetime exposure genetically determined to lower LDL-C, compared to short-term drug-mediated exposure to lower LDL-C, implying that LDL has causal and cumulative effects on CVD risk. What's more, when adjusted for a standard decrease in LDL-C, each of the genetic variants associated with LDL-C has a similar effect on CVD risk per unit of lower LDL, including mutations in genes that encode targets for drugs used to lower LDL-C such as statins. ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors. Overall, Mendelian randomisation studies provide robust data on the causal role of LDL in CVD risk, and the fact that this effect is largely independent of the mechanism of LDL-C reduction.

ConclusionIn reference to the role of hypercholesterolemia, at the expense of the increase in LDL-C, in the cardiovascular risk continuum, when a patient presents a cardiovascular event, whether coronary or extracoronary, it is in the field of secondary prevention; this should be interpreted from the pathophysiological point of view as the failure of primary prevention. The lower the LDL-C reduction in people with CVD, advanced subclinical atherosclerosis, myocardial dysfunction, diabetes or renal insufficiency, the better and this treatment should be considered as etiological treatment of atherosclerotic disease, and not as true prevention. The causal effect of LDL and apoB-containing lipoproteins on cardiovascular risk is conditioned by the degree and duration of exposure to these particles. In the absence of lipid deposition in the arterial wall, inflammation is minimal or non-existent and there is no atherosclerosis. In other words, without LDL-C there is no atherosclerosis, so the evolution of the disease is modifiable, and even reversible.

Ethical responsibilitiesNone.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processThe authors declare that they have not used AI or AI-assisted technologies in the manuscript writing process.

FundingNovartis Farmacéutica SA has financed this monograph; however, they did not intervene in its drafting or content.

Additional informationThis article is part of the supplement entitled "New horizons in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia", which was funded by the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis, with sponsorship from Novartis.

Please cite this article as: J. Pedro-Botet, E. Climent and D. Benaiges, El colesterol LDL como agente causal de la aterosclerosis. Clinica e Investigacion en Arteriosclerosis, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arteri.2024.07.001