Current guidelines recommend a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLc) target of <70mg/dl for patients with coronary artery disease. Despite the well-established benefits of strict lipid control, the most recent studies show that control rate of lipid targets are alarmingly low.

An analysis was performed on the lipid targets attained according to current guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in coronary patients in a Caceres healthcare area.

MethodsAn observational and cross-sectional study was carried out in a healthcare area in Caceres (Spain). The study included a total of 741 patients admitted for coronary disease between 2009 and 2015 with available lipid profile in the last 3 years. Total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLc), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLc), triglycerides (TG) and non-HDLc were analysed.

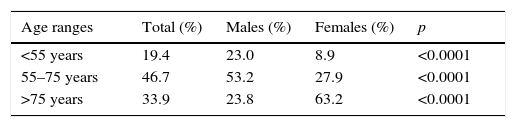

ResultsThe majority (74.4%) of patients were male, with a mean age of 68.5±13.1 years; 76.3±11.8 for women and 65.8±12.6 for men (p<0.001).

A total of 52.3% patients achieved the LDLc target of <70mg/dl, with no gender differences. Only 44.8% of the patients <55 years achieved their lipid targets, compared to 59.3% of the patients >75 years.

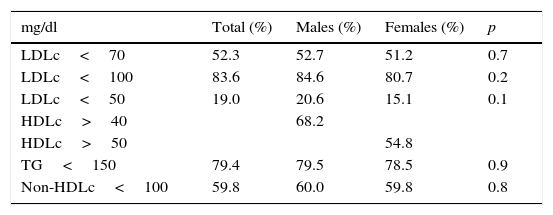

About 68.2% of men had an HDLc>40mg/dl, and 54.8% of women had an HDLc>50mg/dl. Overall, 79.4% of patients had a TG<150mg/dl, with no gender differences, and 59.8% had a non-HDLc<100mg/dl.

ConclusionsApproximately one half of patients with coronary disease do not achieve their target lipid levels as defined in the European guidelines, and this rate is less than reported in previous studies.

There are no gender differences in achieving lipid goals, and age is a predictor of adherence.

En pacientes con enfermedad coronaria las guías establecen como objetivo un colesterol asociado a lipoproteínas de baja densidad (cLDL) <70mg/dl. A pesar de las evidencias del beneficio de un estricto control lipídico, el grado de consecución de objetivos es alarmantemente bajo en los estudios más recientes.

Hemos analizado el grado de cumplimiento de objetivos lipídicos en pacientes coronarios de nuestra área sanitaria.

MétodosEstudio observacional y transversal realizado en el Área de Salud de Cáceres (España). Se incluyeron 741 pacientes coronarios ingresados entre 2009-2015 con un perfil lipídico en los últimos 3 años. Se analizaron: colesterol total, cLDL, colesterol asociado a lipoproteínas de alta densidad (cHDL), triglicéridos (TG) y colesterol-no-HDL.

ResultadosEl 74,4% eran varones. La edad media fue de 68,5±13,1 años: 76,3±11,8 en las mujeres y 65,8±12,6 en los varones (p<0,001).

El 52,3% tenían un cLDL<70mg/dl, sin diferencias entre sexos; estaban en objetivos el 44,8% de los pacientes <55 años frente al 59,3% de los >75 años.

Tenían un cHDL>40mg/dl el 68,2% de los varones y un cHDL>50mg/dl el 54,8% de las mujeres. Mostraron unos TG<150mg/dl el 79,4%, sin diferencias entre sexos, y un colesterol-no-HDL<100mg/dl el 59,8%.

ConclusionesLa mitad de pacientes coronarios no alcanzan los objetivos de control lipídico, y esta proporción es muy inferior a la comunicada en estudios previos.

No existen diferencias en el cumplimiento de objetivos por sexos, y la edad es un predictor de cumplimiento.

One of the principal determinants of cardiovascular risk in patients with coronary disease (CD) is changes in the lipid metabolism.

The majority of interventional studies have reported beneficial cardiovascular effects with a decrease in plasma levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLc) and have shown that LDLc values of <70mg/dl are related to a decrease in cardiovascular events and mortality in high-risk subjects. The European clinical practice guidelines for dyslipidaemia and cardiovascular prevention1,2 seek a target LDLc of <70mg/dl in patients at very high cardiovascular risk. Recently, LDLc figures of ≈50mg/dl have shown additional benefits in cardiovascular prevention3 and are related to a reduction in the volume of plaque and an increase in vascular lumen.4 More recently, the IMPROVE-IT study just corroborated the lipid theory by demonstrating that the further LDLc levels were lowered, the better prognosis was obtained, regardless of how they were lowered.5

What is known as the atherogenic lipid triad can appear in many patients with CD and is expressed by a moderate increase in plasma triglycerides (TG) levels and particles of LDLc and a decrease in levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLc), all combined in the figure for non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDLc).6 The existence of small, dense particles of LDLc have been described in these patients; they can appear with apparently normal LDLc numbers, similar to those observed when there is a lower number of LDLc particles of larger size. The apolipoprotein B numbers in these cases are a reliable marker of the number of circulating atherogenic particles capable of crossing and depositing in the arterial wall, and an adequate surrogate for apolipoprotein B is non-HDLc. A recent meta-analysis of 62,154 patients included in 8 studies showed that non-HDLc correlated better with cardiovascular risk than LDLc.7 Some authors therefore rely on the use of apolipoprotein B or non-HDLc and have proposed cut-off target values for non-HDLc of 30mg above the cut-off values for LDLc.

There is a general consensus that the increase of LDLc and non-HDLc are the most important lipid values for prognostic purposes. However, even in the presence of optimal LDLc levels, there is an increased residual risk of atherothrombotic complications related to low HDLc and high TG. Therefore, when the target values of LDLc have been reached, attention must be paid to the increase in plasma TG and low HDLc levels since both contribute to the residual cardiovascular risk.8

Knowledge of the real degree of control of lipid levels in patients at very high cardiovascular risk, such as coronary patients. It is essential to be able to establish strategies that improve results. To do this, control over lipid levels in the blood must be maximised, therapeutic inertia, which in a recent study was estimated at 73%,9 must be minimised, and adherence to treatment through combined treatment10 must be improved.

The objectives of the LIPICERES study are:

- -

To determine the degree of lipid control in CD patients in our healthcare area (absence of adherence to targets for LDLc, non-HDLc and the presence of low HDLc and high TG).

- -

To investigate whether age and gender are predictions of adherence to the lipid targets.

This is an observational, cross-sectional and non-interventional study conducted in the Cáceres Healthcare Area (Extremadura, Spain). All patients admitted subsequently to our hospital with a diagnosis of CD (acute or chronic) from January 2009 to June 2015 and for whom a recent lipid profile dating from 2013 to 2015 was available were included. If there was more than one lipid profile performed in this period, the most recent one was chosen. The analyses might have been prescribed by their family physician or in hospital, provided that they included a complete lipid profile. 12.7% of the analyses were from 2013, 14.6% from 2014 and 72.7% from 2015. All patients received high-intensity treatment with statins, unless contraindicated or there were special circumstances that affected patient safety as established in the European Guidelines for Clinical Practice1,2; if the targets were not achieved, ezetimibe was added to the treatment.

Data was obtained from 741 patients, 550 male (74.4%) and 191 female (25.6%). Only age and gender were collected as clinical data.

Compliance with ethics guidelines: the protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Cáceres (CREC-Cáceres). Protection was guaranteed for the patients’ personal data.

All patients followed the usual treatment for CD, including lipid-lowering treatment. Participating in the study did not change patient management.

Statistical analysisThe statistics were analysed with the IBM SPSS 20.0 statistical program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States). The quantitative variables are presented as mean±standard deviation and the means were compared with the Student t test; the qualitative variables were presented as percentages and the comparisons were studied with the χ2 test. The statistical tests used a statistical significance level of 0.05.

Results741 patients were included. 74.4% were males. The mean age was 68.5±13.1 years: women's age was 76.3±11.8 and that of males was 65.8±12.6 (p<0.0001).

Regarding age distribution, 33.9% were over 75 years old; 21.9% were older than 80 years and 3.2% were over 90 years old. 19.4% of the patients were under 55 years of age.

The distribution by age range and gender is shown in Table 1. Males predominate at the younger ages, but as age advances, the number of women increases, such that above 75 years of age, the proportion of women is more than twice that of men.

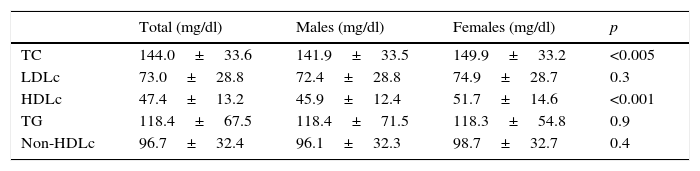

The mean lipid values are shown in Table 2. There were statistically significant differences between males and females at the levels of total cholesterol (TC) and HDLc.

Mean lipid parameter values (mean±SD).

| Total (mg/dl) | Males (mg/dl) | Females (mg/dl) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC | 144.0±33.6 | 141.9±33.5 | 149.9±33.2 | <0.005 |

| LDLc | 73.0±28.8 | 72.4±28.8 | 74.9±28.7 | 0.3 |

| HDLc | 47.4±13.2 | 45.9±12.4 | 51.7±14.6 | <0.001 |

| TG | 118.4±67.5 | 118.4±71.5 | 118.3±54.8 | 0.9 |

| Non-HDLc | 96.7±32.4 | 96.1±32.3 | 98.7±32.7 | 0.4 |

HDLc: cholesterol combined with high-density lipoproteins; LDLc: cholesterol combined with low-density lipoproteins; non-HDLc: non-HDL cholesterol; TC: total cholesterol; SD: standard deviation; p: statistical significance <0.05; TG: triglycerides.

The degree of adherence to the lipid targets is shown in Table 3. More than half our patients met the LDLc target of <70mg/dl, and more than 80% had a LDLc of <100mg/dl; almost 1 out of 5 patients had a LDLc of <50mg/dl; the degree of compliance with the targets was similar in males and females. A proportion of nearly 60% had a non-HDLc of <100mg/dl, similar in males and females.

Degree of adherence to lipid targets.

| mg/dl | Total (%) | Males (%) | Females (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDLc<70 | 52.3 | 52.7 | 51.2 | 0.7 |

| LDLc<100 | 83.6 | 84.6 | 80.7 | 0.2 |

| LDLc<50 | 19.0 | 20.6 | 15.1 | 0.1 |

| HDLc>40 | 68.2 | |||

| HDLc>50 | 54.8 | |||

| TG<150 | 79.4 | 79.5 | 78.5 | 0.9 |

| Non-HDLc<100 | 59.8 | 60.0 | 59.8 | 0.8 |

HDLc: cholesterol combined with high-density lipoproteins; LDLc: cholesterol combined with low-density lipoproteins; non-HDLc: non-HDL cholesterol; TC: total cholesterol; p: statistical significance <0.05; TG: triglycerides.

Regarding other secondary lipid targets related to residual risk, 64.9% of the patients had adequate HDLc values, and 79.4% had TG in the optimum ranges, in similar proportions for males and females.

When we look at adherence to LDLc lipid targets of <70mg/dl for the age groups established above, we see that 44.8% of those <55 years old met the objective, compared to 54.2% of those >55 years (p=0.05); in the middle-aged group (between 55 and 75 years) 50.8% of patients met the LDLc objective compared to 53.7% in the other age groups (p=0.45); and with regard to the older patients, 59.3% of those >75 years had a LDLc of <70mg/dl compared to 49.0% of those <75 years (p=0.013).

In patients whose analyses were performed in 2013 and 2014 (n=202), the mean LDLc values were 78.5±28.7mg/dl, and 44.1% met the LDLc target of <70mg/dl, while those whose analyses were performed in 2015 (n=539) showed mean LDLc values of 71.0±28.6mg/dl and 55.9% met the LDLc target of <70mg/dl (p=0.003).

DiscussionDyslipidaemia has been identified as the principal risk factor for CD,11,12 and CD mortality is related directly to serum LDLc values,7,13,14 such that a reduction of 1mmol/l (≈39mg/dl) causes a 21% reduction in the incidence of major cardiovascular events and 23% reduction in coronary events.15 Most consensuses on cardiovascular prevention therefore base the intervention targets on LDLc levels, as the majority of intervention studies have reported beneficial cardiovascular effects with a decrease in plasma levels of LDLc and have shown that LDLc values of <70mg/dl are related to a decrease in cardiovascular events and mortality in high-risk subjects; figures of LDLc≈50mg/dl have recently shown additional benefits in cardiovascular prevention3,5 and are related to a reduction in the volume of atheromatous plaque and an increase in vascular lumen.4

To achieve the LDLc targets, we use changes in lifestyle, control of other risk factors, a lipid-lowering, normal calorie diet, and drugs, basically statins, that have an IA indication in patients with CD.

However, despite the well-established benefits of strict lipid control, the target achievement rate in this group of patients at very high risk of CD is alarmingly low in the studies.

The EUROASPIRE I, II and III studies determined TC numbers in CD patients in 1995–1996, 1999–2000 and 2006–2007, and although the trend over time is positive, the TC numbers continue to be unacceptably high.16 In EUROASPIRE IV,17 conducted in 2012–2013, 87% of patients with CD were undergoing treatment with statins, but only 21% had a LDLc of <70mg/dl and 58% of <100mg/dl.

In the L-TAP study, conducted in the United States in 1996–1997, it was found that LDLc targets of <100mg/dl were achieved in only 18% of the patients with CD.18 The L-TAP 2 study, conducted 10 years later in 9 countries, including Spain, showed better results than the initial study, but even there nearly one-third of the patients did not reach the LDLc targets of <100mg/dl, and only 30% reached the LDLc target of <70mg/dl.19

The Italian registry BLITZ-4 included 11,706 patients assessed at 6 months after a coronary event, and only 24% had a LDLc of <100mg/dl.20

Many other studies have shown similar data evidencing poor lipid control in high-risk patients. The EURIKA and REALITY studies conducted in 12 and 10 European countries, respectively, including Spain, also showed high levels of patients at high cardiovascular risk with poor lipid control.21,22 With respect to the studies conducted in Spain, in the DYSIS-Spain study, the rate of patients with CD and a LDLc of >100mg/dl was 51.3%, while patients with a LDLc of >70mg/dl were greater than 90%.23

A recent systematic review of the literature in 120 publications from 2010 to 2014, evaluating the degree of lipid control achieved in Spanish patients at high cardiovascular risk24 establishes that, despite the high proportion of patients with CD treated, only between 26 and 55% of patients treated had LDLc levels of <100mg/dl, and a much lower proportion had LDLc levels of <70mg/dl.

In the DARIOS study, which included about 28,000 individuals starting in 2000, scarcely 1% of the males and 2% of the females with diabetes or high or very high cardiovascular risk attained the LDLc targets of <100mg/dl.25

The ENRICA study, conducted on more than 11,000 patients in Spain between 2008 and 2010, showed that among patients with CD and high LDLc on pharmacological treatment, only 43.6% had an LDLc of <100mg/dl, and only 5.2% had an LDLc of <70mg/dl.26

In the CODIMET study, whose data were collected in 2006, the mean LDLc values in coronary patients were 112.7±36.0 and the proportion with LDLc of >70mg/dl was 88.4%27; in a registry of patients with acute coronary syndrome in Toledo in 2005–2008, only 14.1% of patients with acute coronary syndrome had an LDLc of <70mg/dl,28 similar to the data from CODIMET. In LIPICERES, the mean LDLc values were 73.0±28.8mg/dl, practically 40mg/dl less than in CODIMET, and the proportion of patients with a LDLc of >70mg/dl was 47.7%, almost half that from CODIMET, only 8–9 years later.

In the ELDERCIC study, the outpatient management of patients with chronic CD treated by cardiologists in Spain was analysed based on age; they had a LDLc of <100mg/dl, a number that was similar in patients older and younger than 65 years (42.4% vs 46.5%)29 and almost 83% of the patients were taking statins, with no significant difference by age. In LIPICERES, 59.3% of patients over 75 years of age had a LDLc of <70mg and 49% of those under 75 years, this being a significant difference. Various studies have demonstrated that plasma cholesterol varies with the age of the individual, such that it increases gradually after puberty, stabilising around the age of sixty, and then declining in later stages. In the ENRICA study, blood lipids increased with age up to 65 years, except for HDLc, which remained stable.26 This decrease at the end of life is attributed to a combination of an earlier disappearance of hypercholesterolaemic patients due to cardiovascular disease, and a concomitant decrease in weight with age.30

LIPICERES does not show any differences in LDLc control by gender; in the DYSIS-Spain study, female sex was associated independently with LDLc values outside the target range; to the contrary, the history of CD and treatment with high dosages of statins were associated with better LDLc control.23 We believe that in patients at very high risk, especially patients with CD – such as the population in LIPICERES – lipid-lowering treatment is common and intense in males and females, so that both have equal numbers of patients treated.

The apolipoprotein B numbers are a reliable marker of the number of circulating atherogenic particles capable of crossing and depositing in the arterial wall, and an adequate surrogate for the same is non-HDLc. A recent meta-analysis of 62,154 patients included in 8 studies showed that non-HDLc correlated better with cardiovascular risk than LDLc,7 and therefore, the reduction of LDLc values below 100mg/dl was not accompanied by a decrease in incidence of cardiovascular disease unless accompanied by decreases in non-HDLc below 130mg/dl. Some authors therefore rely on the use of apolipoprotein B or non-HDLc and have proposed cut-off values for non-HDLc of 30mg above the cut-off values for LDLc. Nonetheless, current guidelines do not look at principal therapeutic objectives because there are no clinical trials specifically designed for this purpose.

In LIPICERES, the mean non-HDLc values are 96.7±32.4mg/dl, less than the recommended level for patients with CD (<100mg/dl), and 59.8% of coronary patients met this target in our study.

We know that, despite strict control of LDLc, there is still a non-negligible incidence of cardiovascular complications; this concept has been termed “residual lipid risk”31 and it has been observed that it is especially high in patients at high cardiovascular risk.21 In a CD patient registry conducted in Spain, in which 94.1% were on intensive treatment with statins, it was observed that only 55% had LDLc of <100mg/dl and of these, a high percentage had HDLc of <40mg/dl and/or TG of >150mg/dl, i.e., a residual lipid risk.32 In total, 30% of patients had this residual risk.

Therefore, when the target values of LDLc have been reached, attention must be paid to the increase in plasma TG and low HDLc levels since both contribute to the residual cardiovascular risk.8

Lahoz et al. found that in patients with established CD, 26.3% of patients had a low HDLc and 39.7% had high TG.33 In LIPICERES, 11.2% of patients had a residual risk (7.5% of males and 3.7% of females), 35.1% of patients had an HDLc outside of target range and 20.6% had TG values >150mg/dl. The increased prevalence of low HDLc and high TG in our study is not surprising, as the association of diabetes mellitus, a highly prevalent cardiovascular risk factor in patients with CD (such as in the population in LIPICERES), with poor control of HDLc and TG is already known; furthermore, statins, used massively in patients with CD, have little effect on HDLc and TG.23

LIPICERES detected a striking increase in the percentage of patients with LDLc within the target range in 2015 compared to prior years (from 42.8 to 55.9%); it occurred to us that the presentation in late 2014 at the scientific sessions of the American Heart Association (AHA) of the IMPROVE-IT study and its subsequent publication,5 could have had an effect on this improvement in lipid control in our coronary patients in 2015; this study is the first in the past decade that demonstrates a clinical benefit in further lowering LDLc levels (from 65 to 50mg/dl) by reducing cardiovascular events with a “non-statin” pharmaceutical such as ezetimibe, which also has a safe profile. This affirmation must be viewed with caution and confirmed or rejected in later studies demonstrating this trend.

We believe that LIPICERES provides updated knowledge on the real control of the lipid profile in patients with CD in our setting, which can probably be extrapolated to the rest of our country; in addition, they are the first data on lipid control after the presentation of the data from the IMPROVE-IT study, which, most certainly, favourably influenced the attainment of lipid targets in patients at very high risk in the past year.

The LIPICERES study has various limitations and strengths. It is an observational, cross-sectional study that included data from routine clinical practices. We cannot exclude the fact that the data on patients who did not have acute events in the past 7 years (before 2009), and who were not included in the study, could affect our results. LIPICERES only takes lipid values into account and not other clinical variables, except age and sex; we are aware that other clinical and biochemical variables could be predictive of attainment of the lipid targets.

Conclusions- -

Approximately 1 in every 2 coronary patients in our area does not achieve the LDLc targets set in the European guidelines. Although this proportion of patients outside the target range is significant, it is much lower than that reported in previous studies.

- -

The LDLc targets are met similarly in males and females, and age is a predictive factor for achievement of the objectives.

- -

There is a percentage of coronary patients with other out-of-range lipid parameters, such HDLc (almost one-third of males and about half of the females) and TG, which are increased in 1 out of every 5 patients, with the corresponding implications for residual risk.

- -

An increase in the percentage of achievement of objectives for LDLc was observed in 2015 compared to previous years.

The authors declare that no experiments were conducted on human beings or animals for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data is contained in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data is contained in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Antonio González-Peramato Gutiérrez, Director of the Clinical Analyses Department and José Luis Bote-Mohedano, Medical Coordinator for the Admissions and Clinical Documentation Department of Hospital San Pedro of Alcántara, Cáceres.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Barrado JJ, Ortiz C, Gómez-Turégano M, Gómez-Turégano P, Garcipérez-de-Vargas FJ, Sánchez-Calderón P. Control lipídico en pacientes con enfermedad coronaria del Área de Salud de Cáceres (España): estudio LIPICERES. Clin Invest Arterioscler. 2017;29:13–19.