Breast cancer is the most common neoplasm in women. The Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet (HUMS) is a referral center for the Zaragoza II Healthcare Sector in Spain, serving a population of 379 225 inhabitants and treating some 300 new cases of breast cancer per year.

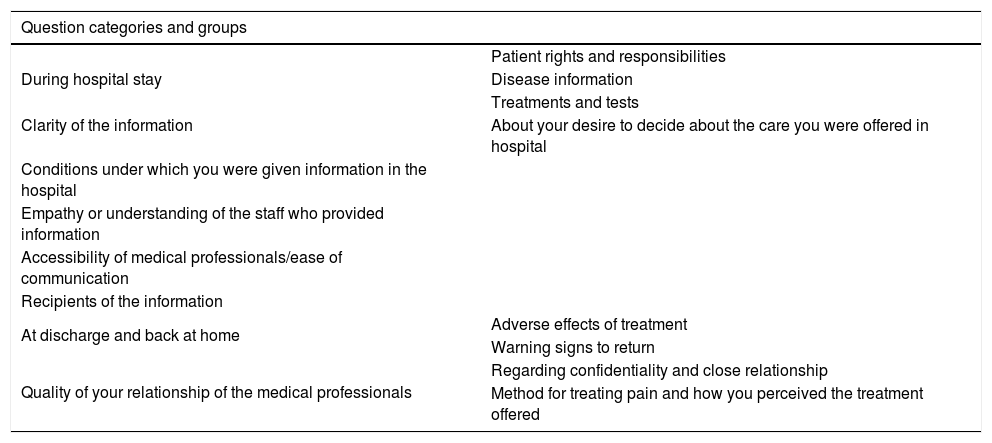

One of the main challenges and priorities of our current healthcare system should be to try to improve the experience of the patients we treat so that the patient is the “cornerstone” of all our actions. This affective-effective model described by Albert Jovell represents a revolution in the humanization of healthcare. In recent years, we have witnessed a proliferation of quality assessment tools that take into account the perspective of patients. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service (NHS) and a non-profit association have jointly developed a survey known as the Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire-15 (PPE-15)1–3. Table 1 lists the dimensions explored.

Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire-33 (PPE-33) — Version adapted and validated for Spanish, consisting of 33 questions grouped into 8 categories.

| Question categories and groups | |

|---|---|

| During hospital stay | Patient rights and responsibilities |

| Disease information | |

| Treatments and tests | |

| Clarity of the information | About your desire to decide about the care you were offered in hospital |

| Conditions under which you were given information in the hospital | |

| Empathy or understanding of the staff who provided information | |

| Accessibility of medical professionals/ease of communication | |

| Recipients of the information | |

| At discharge and back at home | Adverse effects of treatment |

| Warning signs to return | |

| Quality of your relationship of the medical professionals | Regarding confidentiality and close relationship |

| Method for treating pain and how you perceived the treatment offered | |

Our objective is to examine the perception of information and participation in decision making experienced during hospitalization for breast cancer treatment in a context of comprehensive care and humanization.

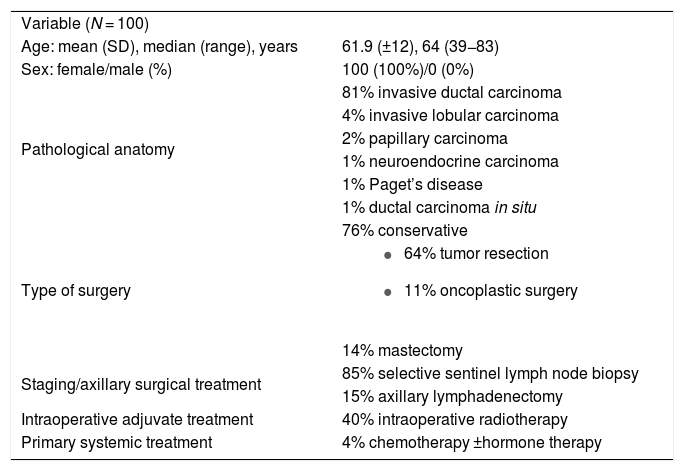

To this end, we have carried out a descriptive observational study of consecutive cases in a target population of adult patients operated on for breast cancer in the General and Digestive Surgery Department of the HUMS during 2021. We proposed using the PPE-15 questionnaire adapted to Spanish in PPE-33, with an initial sample size of 100 cases, whose characteristics are shown in Table 2. This instrument has been considered reliable and valid to explore the perception of information and participation in decision-making for Spanish patients, incorporating new dimensions that were not included in the original version but considered relevant in a previous study1–3. All patients underwent surgery with hospital admission, so the information, surveys and informed consent forms were given to patients at hospital discharge for their later completion at home after the 15th postoperative day. The completed surveys were collected one month after surgery together with the informed consent form for data processing.

Sample characteristics (SD: standard deviation).

| Variable (N = 100) | |

| Age: mean (SD), median (range), years | 61.9 (±12), 64 (39−83) |

| Sex: female/male (%) | 100 (100%)/0 (0%) |

| Pathological anatomy | 81% invasive ductal carcinoma |

| 4% invasive lobular carcinoma | |

| 2% papillary carcinoma | |

| 1% neuroendocrine carcinoma | |

| 1% Paget’s disease | |

| 1% ductal carcinoma in situ | |

| Type of surgery | 76% conservative |

| |

| 14% mastectomy | |

| Staging/axillary surgical treatment | 85% selective sentinel lymph node biopsy |

| 15% axillary lymphadenectomy | |

| Intraoperative adjuvate treatment | 40% intraoperative radiotherapy |

| Primary systemic treatment | 4% chemotherapy ±hormone therapy |

The response rate was only 44% (44 patients), which is somewhat higher than other series of satisfaction surveys (20%–30%)4. However, compared to the validation study of the PPE-33 in the Spanish population1, where losses were 29%, we could consider that we found a selection bias in our sample, assuming that the rate of losses is a weakness of the study. This could be due to the time elapsed between delivery and completion, or due to self-completion. Telephone surveys or personal interviews could increase the response rate. Data analysis revealed that many completed surveys demonstrated a positive assessment for: adequate information about the process (82%), treatment effects (80%), risks of diagnostic tests (71%), clarity (87%), coherence (77%), courtesy (90%), resolution of concerns (76%), appropriateness of time (96%), and respect (98%). However, few patients were aware of the Charter of Patient Rights and Responsibilities (30%), the possibility to reject diagnostic tests (40%), knowledge of the content of the clinical history (58%), and possible warning signs after discharge (30.4%). An important field for improvement can be seen in these factors as well as in the participation of shared decision-making.

The term “dehumanization” refers to a multifactorial problem, which includes: lack of time, waiting lists, lack of communication skills and training in this field, or the judicialization of medicine, etc. When patients are given the news that they are facing cancer, this threatens their physical integrity, which causes anxiety and fear of the unknown. The information that we are capable of transmitting in a professional, humane, empathetic and trustworthy manner contributes towards lessening the negative impact, which is beneficial for the patient and specialist as well. Reduced anxiety, stress and pain, along with the use of medication, accelerate recovery and ultimately improve patient quality of life5–9.

In Spain, research has also been conducted in this regard in accordance with different methods, such as the SERVQUAL application10. However, the use of sociological surveys developed by official organisms (Health Barometer by the Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumption; or surveys in the autonomous communities) has become more widespread. Most surveys about patient opinions regarding healthcare services contain general information and participation questions, and it is striking that the results show this as an area for improvement, especially in the responses of younger patients.

Knowledge about our patients’ perception of the information we provide has allowed us to start a series of improvement projects: printed copies of the Charter of Patient Rights and Responsibilities provided to patients, a suggestion box, the 1st Aragonese Conference on Humanization in Breast Cancer, and specific training courses on quality care and humanization.

The analysis of the survey data has provided us with a “diagnosis” of the reality that our patients perceive in order to move towards humanization and implement patient-centered measures to improve treatment.

FundingThe authors have no source of funding to declare.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.