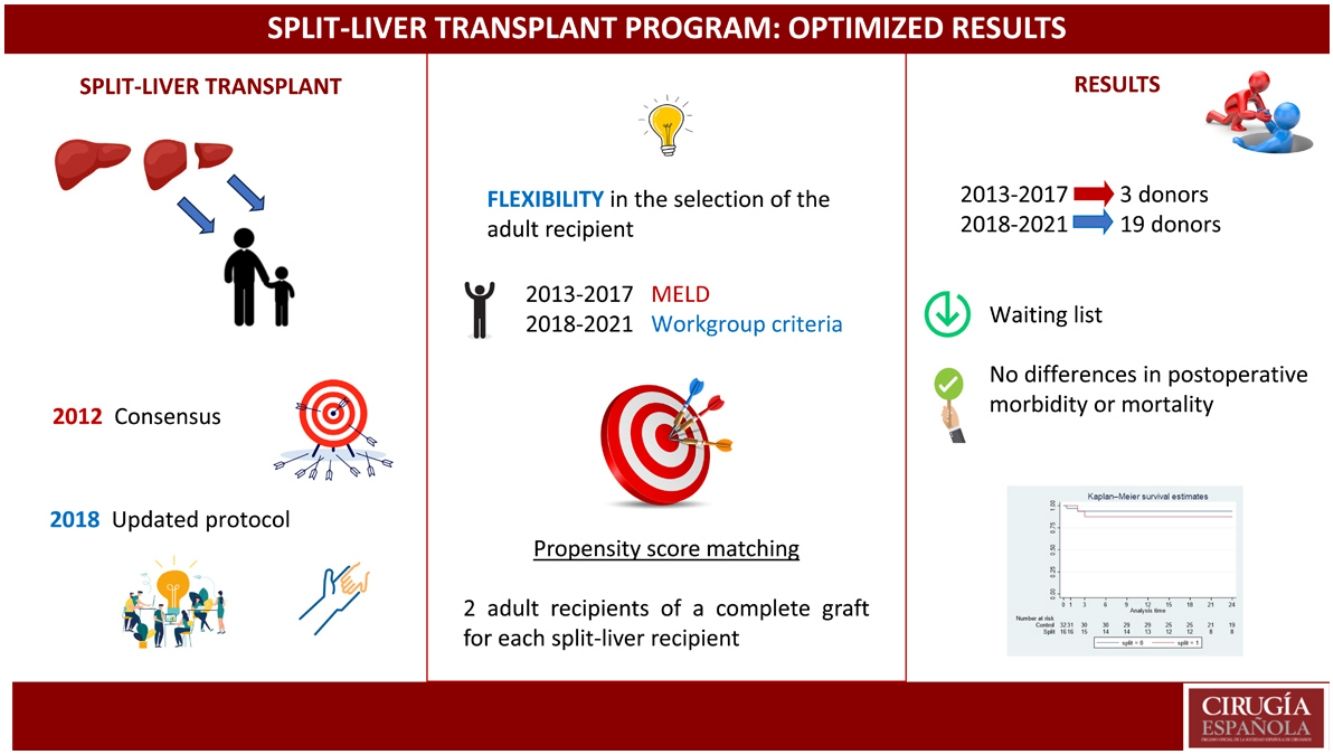

Split liver transplantation is a procedure performed throughout Europe. In 2018 in Catalonia, the distribution of donors was redefined, being potential candidates for SPLIT all those under 35-years and it was made flexible the adult selection for the right graft. The study aim is to evaluate the effect of this modifications on the use of Split donors on the adult/pediatric waiting lists, as well as to evaluate the post-transplant results of adults who received a Split donor.

MethodsObservational and retrospective study; 2 data collection periods "PRE" (2013–2017) and "POST" (2018–2021). The adults recipients results were analyzed by a propensity score matching.

ResultsIn the first period 3 donors were registered and 3 pediatric patients and 2 adults recieved a transplant. In the POST period, 24 donations with liver bipartition were made, performing the transplant in 19 adults and 24 childrens. When comparing the adults waiting lists, a significant decrease was evidenced, both for adults (p = 0,0001) and on the children's waiting list (p = 0,0004), and up to 3 times there were no recipients on the pediatric waiting list. No significant differences between hospital morbidity or mortality or overall survival were observed in the group of adult recipients of Split grafts.

ConclusionsThe flexibility in the selection of the adult recipient and the new distribution of donors makes possible to increase the bipartition rate, reducing the pediatric waiting list without worsening the adults results transplant recipients or their permanence on the waiting list.

El trasplante hepático “Split” es un procedimiento extendido por toda Europa. En 2018 en Cataluña, se redefinió la distribución de donantes, siendo candidatos potenciales para SPLIT todos aquellos menores de 35 años y se flexibilizó la selección del adulto para el injerto derecho. El objetivo del estudio es evaluar el efecto de estas modificaciones en la utilización de donantes para Split, en las listas de espera y en los resultados de los adultos que recibieron un injerto Split.

MétodosEstudio observacional y retrospectivo; 2 periodos de recogida de datos “PRE” (2013–2017) y “POST” (2018–2021). Los resultados de los receptores adultos se analizaron mediante un propensity score matching.

ResultadosEn el primer período fueron registrados 3 donantes y se trasplantaron 3 pacientes pediátricos y 2 adultos; en el periodo POST se obtuvieron 24 donantes, realizándose el trasplante en 19 adultos y 24 receptores infantiles. Al comparar las listas de espera se evidenció una disminución significativa tanto en la de adultos (p = 0,0001) como en la infantil (p = 0,0004) y hasta en 3 ocasiones no hubo receptores en la lista de espera infantil. No se observaron diferencias significativas en cuanto a morbilidad o mortalidad, ni en la supervivencia global en el grupo de receptores adultos de injertos Split.

ConclusionesLa flexibilidad en la selección del receptor adulto y la nueva distribución de donantes permite aumentar la tasa de bipartición, permitiendo reducir la lista de espera pediátrica sin afectar los resultados en los trasplantados adultos ni su estancia en lista de espera.

In 1984, Bismuth and Houssin described the first liver reduction procedure after reducing a liver graft for transplantation in a pediatric recipient, using the left lateral sector and discarding the rest.1,2 In 1988, Pichlmayr carried out the first ex-situ split, which was transplanted to a child and an adult.3 In 1996, Rogiers published a series with in-situ liver partitions, which was also used for transplantation in a pediatric recipient.4

In Spain, the first partition of a liver graft for transplantation in an adult and a child was conducted in 1992 at the Hospital Valle de Hebron in Barcelona.5 This technique has been used throughout Europe to transplant low-weight pediatric patients who tend to spend a long time on the transplant waiting list (WL), and therefore have a high risk of mortality. The North Italian Transplant program (NITp) leads one of the most successful multicenter programs in the world for split-liver transplants, having performed more than 400 adult-child split transplantations.6,7 In the United Kingdom, all potential split-liver donors are initially offered in the pediatric “pool” where the pediatric recipient becomes the index case for the graft.

In Catalonia in 2012, the Catalan transplant groups reached an agreement to publish a consensus document, which established that all livers from brain dead donors who presented certain characteristics (age ≤50 years, weight ≥60 Kg, BMI ≤ 28) would be evaluated for split-liver donation. However, in clinical practice, implementation of the program has been very low. This meant maintaining the living donor program of the pediatric liver transplant program at the Hospital Valle de Hebron, and even so the waiting list for children remained high, with an average wait of 256 days.

To address this situation, the consensus document was updated in 2018 in Catalonia to include modifications to the split-liver protocol that would improve its implementation. The main modification was to allow the transplant group receiving the adult graft to choose the most suitable recipient for this procedure from their waiting list, regardless of prioritization. This would increase the confidence in the procedure of the adult transplant group, without harming the general pool and still maintaining the results.

Therefore, after this update, we plan to evaluate the effect of the modification to the split-liver protocol in 2018 versus the period prior (2013–2017) regarding the use of candidate donors for split-liver donation, the impact on the waiting lists for adult and pediatric recipients, and the post-transplantation outcomes of adult recipients who received a graft from a split-liver donor.

MethodsThis is an observational, retrospective, multicenter study with the participation of the 3 liver transplant (LT) teams of Catalonia: the Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, the Hospital Clinic de Barcelona and the Hospital Valle de Hebron. Two data collection periods were established, defined as “PRE” (2013–2017) and “POST” (2018–2021).

The selection of the sample was carried out by propensity score matching, taking into account the characteristics of the recipients: year of transplantation, age, MELD and BMI. Based on these data, 2 transplant recipients were selected: one complete graft recipient for each split-liver recipient. All patients included in the study are adults. All urgent cases, retransplants, multi-organ transplants and donation in asystole were excluded. All SPLIT transplants from donors from the National Transplant Organization (NTO) were also excluded from the analysis since they were not the subject of this study, and their use would not reflect the effect on the change in our protocol.

The data were obtained from the Liver Transplant Registry of Catalonia (RTHC) and the Catalan Transplant Organization (OCATT) of the Catalan Health Service, as well as the databases of each medical center.

According to the Consensus Document for Liver Partition of potential split-liver (child/adult) donors updated by the liver transplant programs in 2018 in Catalonia, split-liver donors were defined as those with an age >16 and <50 years, a weight up to 60 kg, Intensive Care Unit stay (ICU) for less than 5 days, normal ALT and AST or <3 times the normal value, GGT < 500 U/L, who were brain-dead donors. Likewise, the “classic” surgical technique of liver partition was performed as described in said document. Regarding the choice of the adult recipient, the main modification was based on leaving this decision to the discretion of the adult transplant group to choose the most appropriate recipient from the waiting list, without considering MELD prioritization, as previously mentioned.

To assess the impact of the modifications to the split-liver program, we evaluated the length of time on the waiting list for both adult and pediatric recipients. To evaluate post-transplantation results, short- and long-term morbidity were defined as the main variables, including arterial, venous, and biliary complications. The secondary variables included the characteristics of the recipients in terms of admission prior to transplant, need for renal replacement therapy, surgery characteristics (cold ischemia time, duration of the intervention, presence or absence of reperfusion syndrome, types of arterial, venous and biliary anastomoses). Regarding the post-transplantation evolution, we also analyzed the analytical evolution (glomerular filtration rate [GFR], bilirubin [B], aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine aminotransferase [ALT]), extubation time, rate of primary graft dysfunction according to the Olthoff criteria,8 need for retransplantation, overall survival and mortality rate.

Categorical variables have been described using frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables have been described using the mean and standard deviation. The chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables. For ordinal variables, the Mann-Whitney test was performed, and for continuous variables, the Student’s T test was used. The evolution of analytical parameters was described based on the median, and the comparison between groups was performed with the Mann-Whitney test, while the Friedman test was used for intragroup comparison. The Kaplan Meier method and the Log-rank test were used to calculate survival. The level of statistical significance was set at 5% bilaterally, and the analysis was performed with the STATA 17 statistical package.

ResultsIn the first period, 3 donors were obtained, and 3 L T were carried out in children and 2 in adults. In the second period, 24 potential donations were made for liver partition, resulting in 19 L T performed in adults (2 grafts from the NTO) and 24 in pediatric recipients. Not all grafts were used in adults: on one case, liver partition was rejected because the pediatric recipient required the use of the entire graft; in the other 4, the reasons were related to the adult recipient (lack of compatible recipient, ischemia time, graft size and graft perfusion problems).

We used the propensity score matching method to obtain a sample of 32 controls for the 16 split livers that we have notified from 2018 to 2021, which were included in the study. The 2 donors of the ONT Transplants and 1 case of retransplantation were excluded.

Waiting listWhen comparing the WL of adults from both periods, a significant decrease in time was evident, with an Me of 108 days in the PRE period and 59 in the POST period (P = .0001). Regarding the pediatric WL, a reduction in time was also observed, with an Me of 139 days in the PRE period versus 35 POST (P = .0004), while on 3 occasions there was no waiting list.

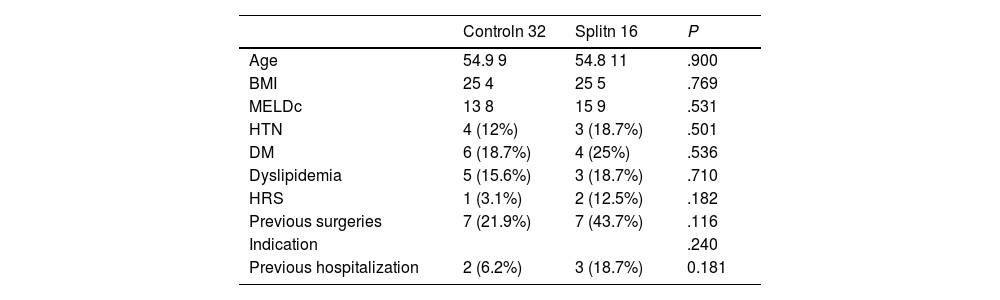

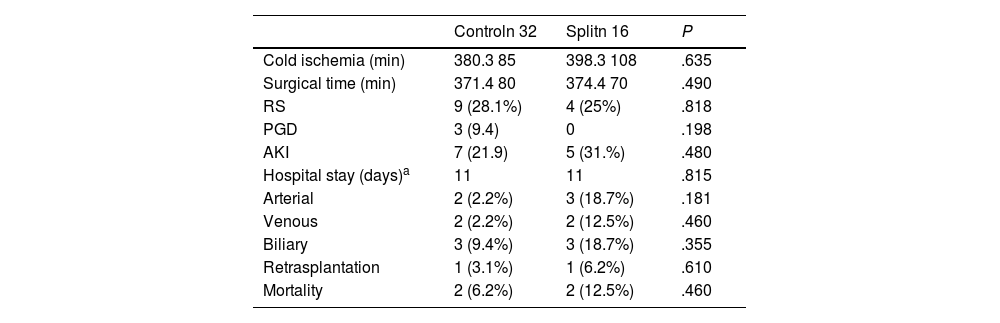

Post-transplant results of adult recipientsRegarding the characteristics of the recipients and the indication for transplantation (acute fulminant hepatitis, cholestatic disease, cirrhosis, metabolic disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, etc) there were no statistically significant differences (Table 1). The ICU stay was longer in the split-liver recipients, (3 days) compared to the control group (2 days; P = .037). The hospital stay was the same in both groups, with a median of 11 days (P = .815). In the split-liver group, 31.2% of the patients presented renal failure, with no significant differences versus the control group (P = .480). When we evaluated the type of vascular or biliary anastomosis, as well as arterial, venous and biliary complications, no differences were found between groups (Table 2).

Characteristics of recipients and indication for transplant.

| Controln 32 | Splitn 16 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54.9 9 | 54.8 11 | .900 |

| BMI | 25 4 | 25 5 | .769 |

| MELDc | 13 8 | 15 9 | .531 |

| HTN | 4 (12%) | 3 (18.7%) | .501 |

| DM | 6 (18.7%) | 4 (25%) | .536 |

| Dyslipidemia | 5 (15.6%) | 3 (18.7%) | .710 |

| HRS | 1 (3.1%) | 2 (12.5%) | .182 |

| Previous surgeries | 7 (21.9%) | 7 (43.7%) | .116 |

| Indication | .240 | ||

| Previous hospitalization | 2 (6.2%) | 3 (18.7%) | 0.181 |

BMI: body mass index; MELD: Model for End-stage Liver Disease; HTN: hypertension; DM: diabetes mellitus; HRS: hepatorenal syndrome.

Surgical variables and complications.

| Controln 32 | Splitn 16 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cold ischemia (min) | 380.3 85 | 398.3 108 | .635 |

| Surgical time (min) | 371.4 80 | 374.4 70 | .490 |

| RS | 9 (28.1%) | 4 (25%) | .818 |

| PGD | 3 (9.4) | 0 | .198 |

| AKI | 7 (21.9) | 5 (31.%) | .480 |

| Hospital stay (days)a | 11 | 11 | .815 |

| Arterial | 2 (2.2%) | 3 (18.7%) | .181 |

| Venous | 2 (2.2%) | 2 (12.5%) | .460 |

| Biliary | 3 (9.4%) | 3 (18.7%) | .355 |

| Retrasplantation | 1 (3.1%) | 1 (6.2%) | .610 |

| Mortality | 2 (6.2%) | 2 (12.5%) | .460 |

RS: reperfusion syndrome; PGD: primary graft dysfunction; AKI: acute kidney injury.

Arterial complications in the split-liver group included: intraoperative dissection of the recipient hepatic artery (one patient), which required an aortic graft for anastomosis; active postoperative bleeding (one patient), which was treated endovascularly (stent); and stenosis, which did not require treatment. In the control group, one patient had mild stenosis and another patient had acute arterial thrombosis that required a new transplant. Regarding venous complications, 2 patients in each group presented complications: in the SPLIT group, one patient had stenosis of a suprahepatic vein, which was treated with a stent, and another patient was diagnosed with portal thrombosis, which was treated with anticoagulation; meanwhile, in the control group, the 2 patients with complications presented portal thrombosis and are in anticoagulant treatment. Three patients in each group presented biliary complications. There were 2 biliary fistula complications and one stricture in the SPLIT group, all of which were treated endoscopically with a stent. In the control group, only two patients presented strictures, which were also treated with endoscopic stent placement and one patient presented ischemic cholangiopathy, requiring retransplantation.

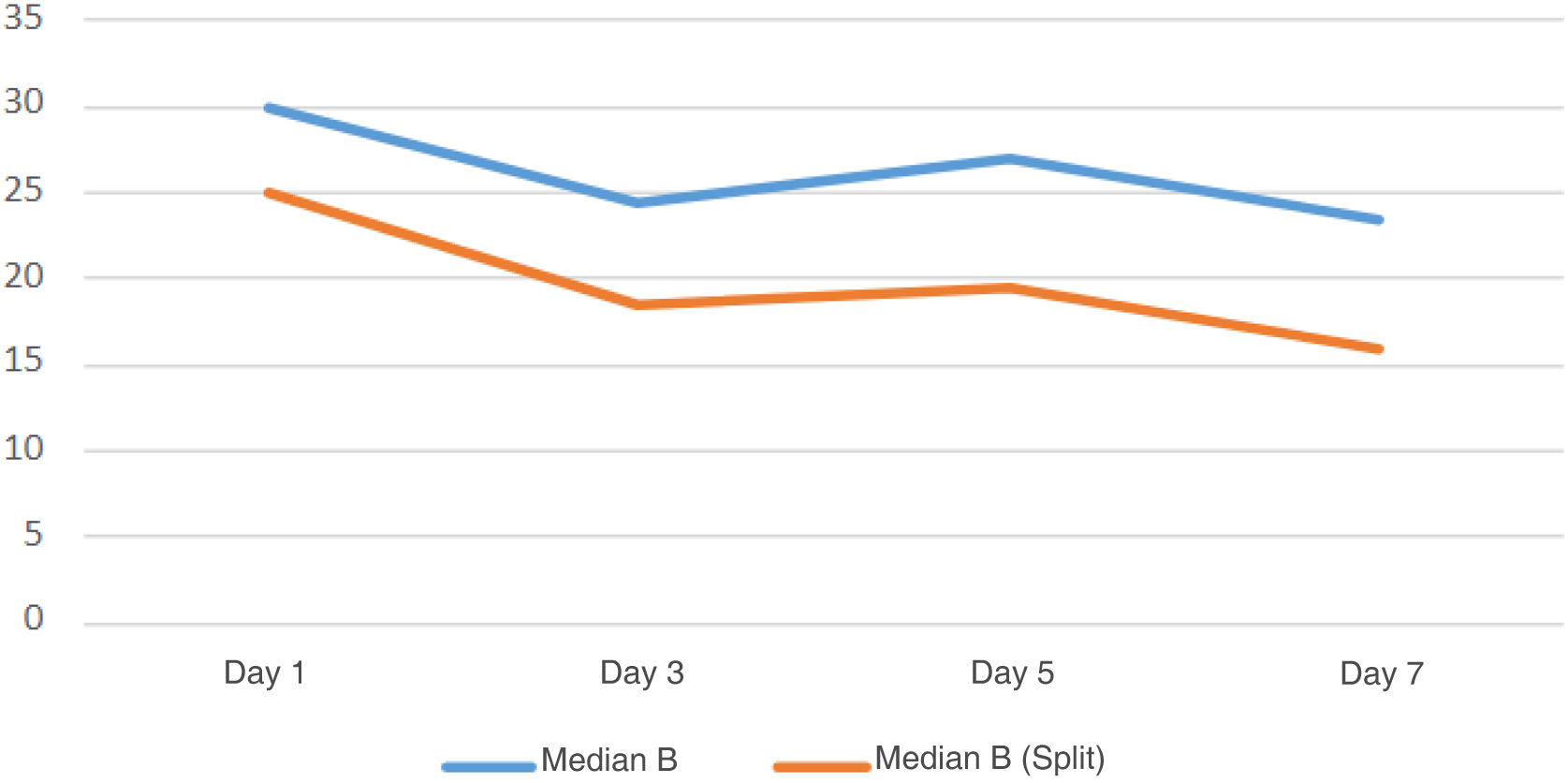

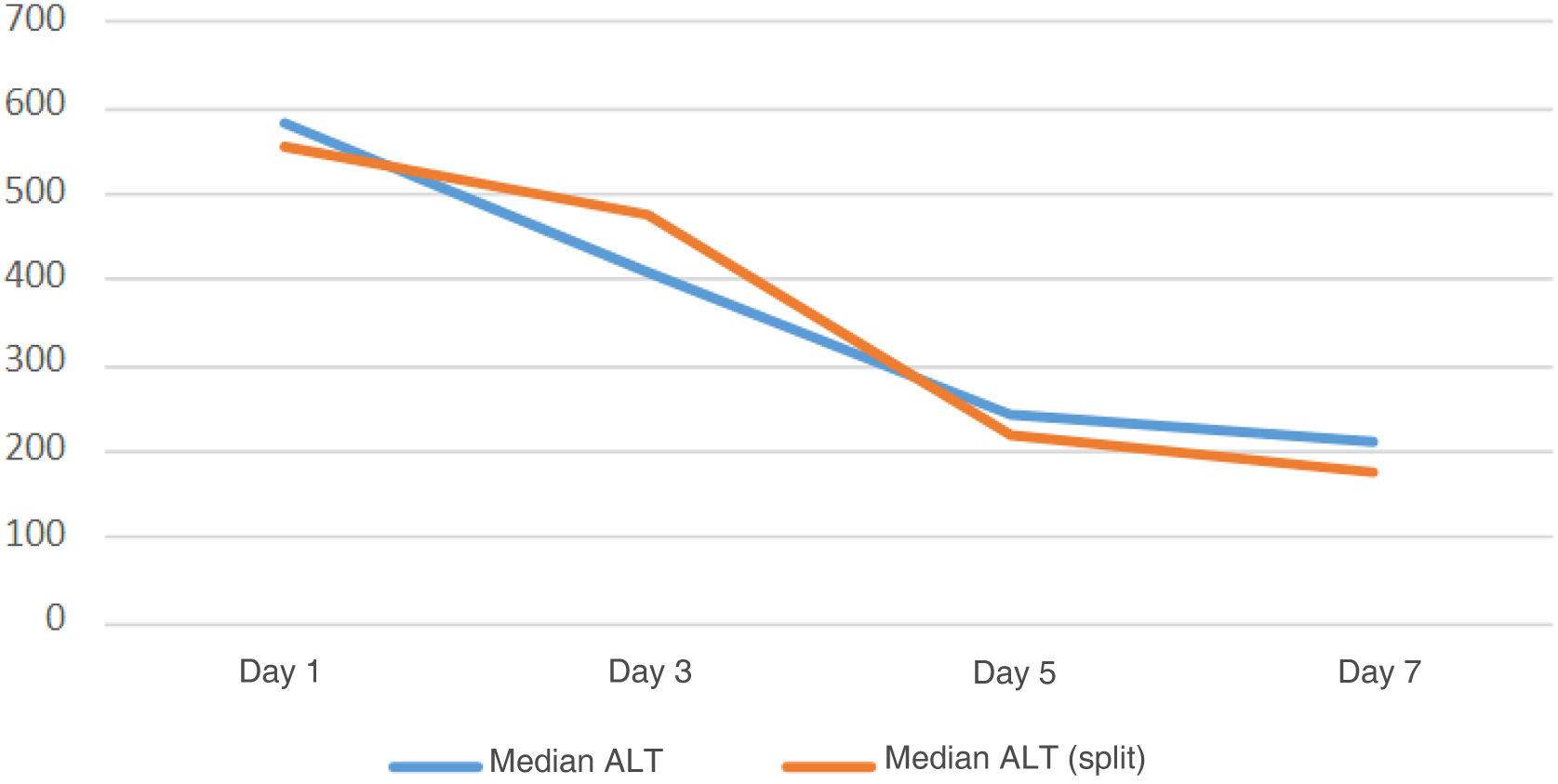

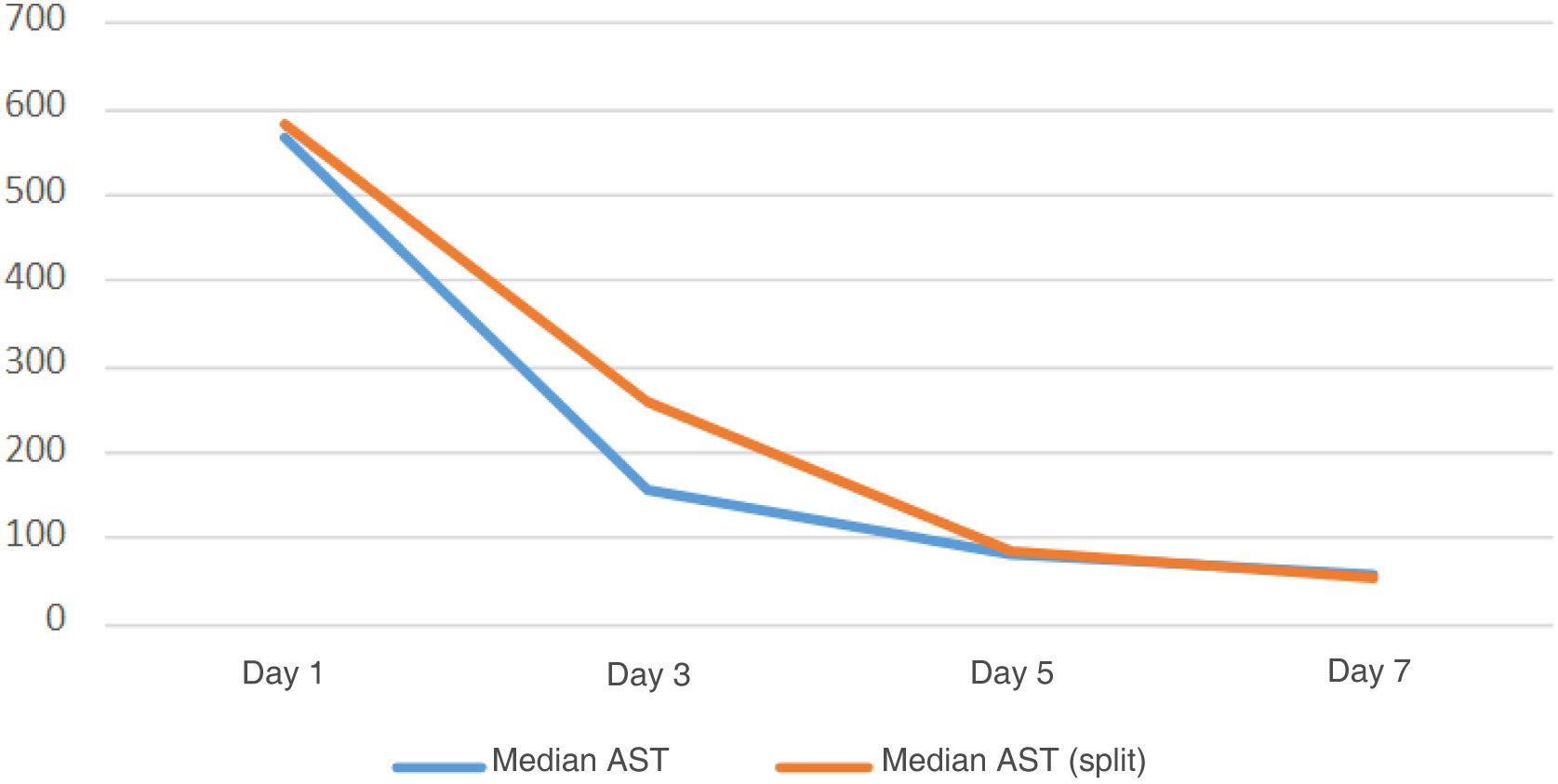

In the SPLIT group, lab analyses showed that the variables of bilirubin, AST, ALT and GFR had a similar median compared to the control group and the SPLIT group on postoperative days 1, 3, 5 and 7 (Figs. 1–3).

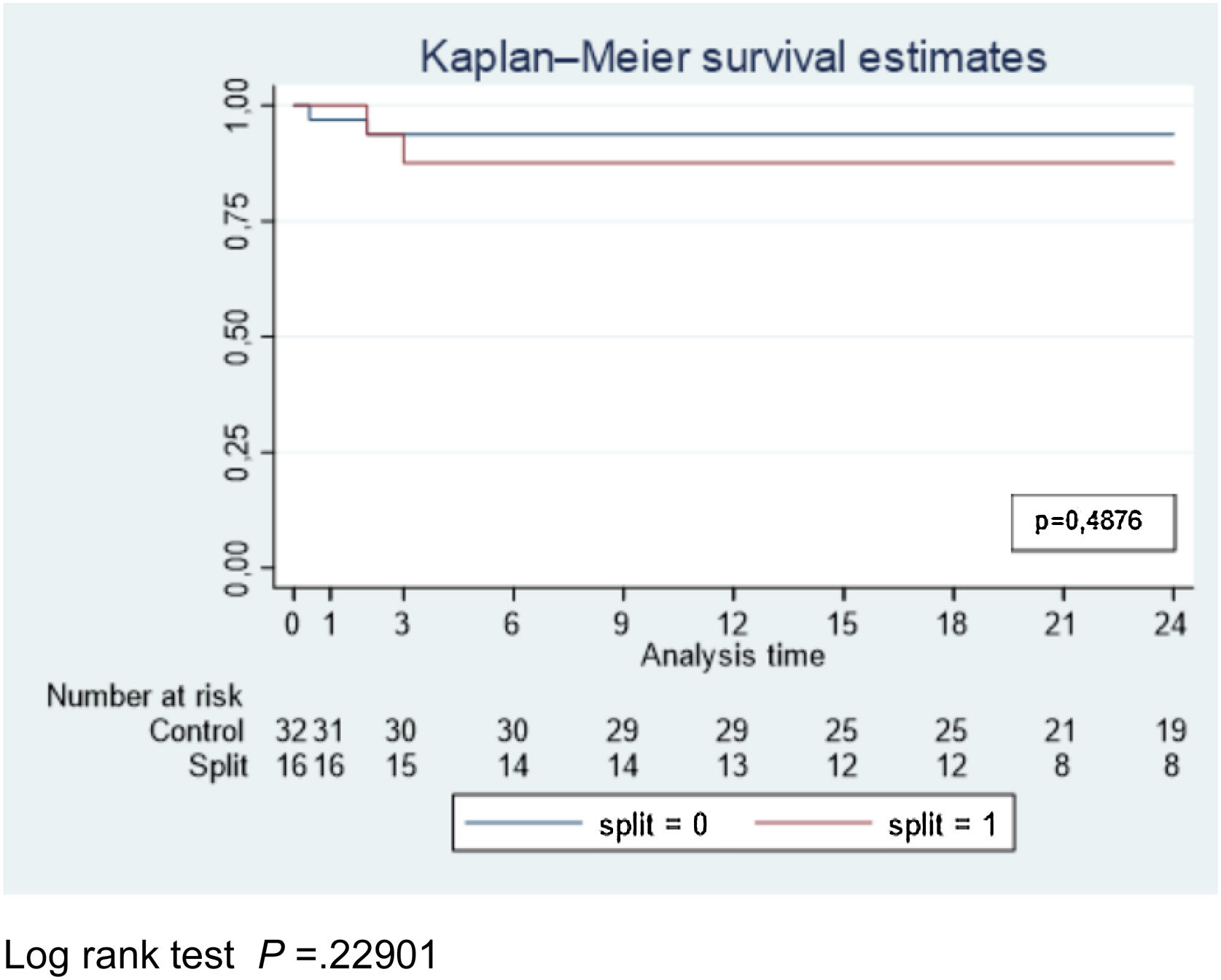

When adult full-graft recipients were compared to split recipients, no statistically significant differences were observed in terms of morbidity, postoperative mortality, or survival (Fig. 4).

DiscussionLT is the only potentially curative treatment for certain patients with end-stage liver disease, both adults and children. Over time, the growing waiting lists, shortage of low-weight donors, use of grafts from living donors with the added risks for the donor, and the risk of mortality on the waiting list have made it necessary to expand donor selection criteria practically around the world. Meanwhile, the use of grafts with liver partition reduces the risks to which pediatric recipients are exposed while waiting for a suitable donor. Regarding the results of adult recipients of a split-liver donation, a meta-analysis has compared the results of adult recipients of split-liver grafts versus complete grafts and showed that biliary and vascular complications were greater in the split-liver group, but there were no differences in overall graft or patient survival.9 Thus, split-liver grafts are considered “higher risk” by some authors, attributed to the prolonged cold ischemia time, smaller graft volume, and more difficult arterial reconstruction.10 Consequently, they are rarely used in recipients who require urgent transplantation or retransplantation.11

In 2021, Ngee-Soon carried out a systematic review of 78 articles on split-liver donations, concluding that advances in the technique have allowed us to overcome many challenges, while generally advocating the use of this type of grafts in more settings and higher risk instances, thus allowing the donor selection criteria to be expanded.12

In Spain, various national strategies have been used to continuously improve the results of the split-liver program. Aimed at prioritizing pediatric recipients and thereby contributing towards shorter waiting list times, these were echoed in the national plan for the promotion of liver partition in April 2018.13 Specifically, the region of Andalusia has implemented a system similar to that of the NITp, dividing all potential split-liver donors, thus being able to transplant an adult and a child with the same liver graft.

In Catalonia, the first initiative of the split-liver program did not have the expected impact and application. In retrospect, a determining factor for the lack of expansion of the procedure could be the regulation to implant the graft from the partition to the first recipient on the waiting list, prioritized by MELD. As the first patient is the most serious case, a split graft was often not considered appropriate due to the high risk. Therefore, updating the protocol was essential. The main modification made it possible to select the most appropriate adult recipient, determined by weight and liver function.

After implementing this modification over a period of time, we believe it is necessary to evaluate the results, both to confirm the benefits for the pediatric waiting list and to confirm 2 factors: (1) that the modified allocation system did not harm the overall group of adult recipients on the list; and (2) that the results of the adults transplanted with grafts from liver partition were comparable to the group with complete grafts. All of this would allow the program to be maintained and give more confidence to the adult transplant teams.

The results of the study confirm both factors. The reduction in the pediatric waiting list has also reduced the need for living donors.

Selection of the optimal adult recipients has proven useful in multiple scenarios. Achieving good post-transplantation outcomes requires an understanding of the interaction between donor, graft, and recipient factors. In this context, and with the appearance of expanded donor criteria, the use of living donors and grafts from donation after circulatory death, it has been necessary to develop tools to help better match donor organs and recipients, even with the use of artificial intelligence techniques.14

Lastly, the results of adult patients transplanted with grafts from bipartition are comparable to the group receiving complete grafts, as shown in a homogeneous sample obtained from the matching system based on year of transplant, age, MELD and BMI. Likewise, these results are comparable to established quality standards.15

The study has 2 main limitations: the sample studied is small, and the follow-up period is short. However, the objective of the study was to analyze the results of the modified system in order to confirm its usefulness and reinforce its application.

After analyzing this experience, we can conclude that both the flexibility for transplant groups to select adult recipients and the new distribution of donors have led to an increased rate of split-liver transplantations. Consequently, waiting lists for pediatric transplant recipients have been reduced without negatively affecting the results in adult transplant recipients.

FundingThis work has not received any funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.