Performing the surgical procedure in a high-volume center has been seen to be important for some surgical procedures. However, this issue has not been studied for patients with an anal fistula (AF).

Material and methodsA retrospective multicentric study was performed including the patients who underwent AF surgery in 2019 in 56 Spanish hospitals. A univariate and multivariate analysis was performed to analyse the relationship between hospital volume and AF cure and fecal incontinence (FI).

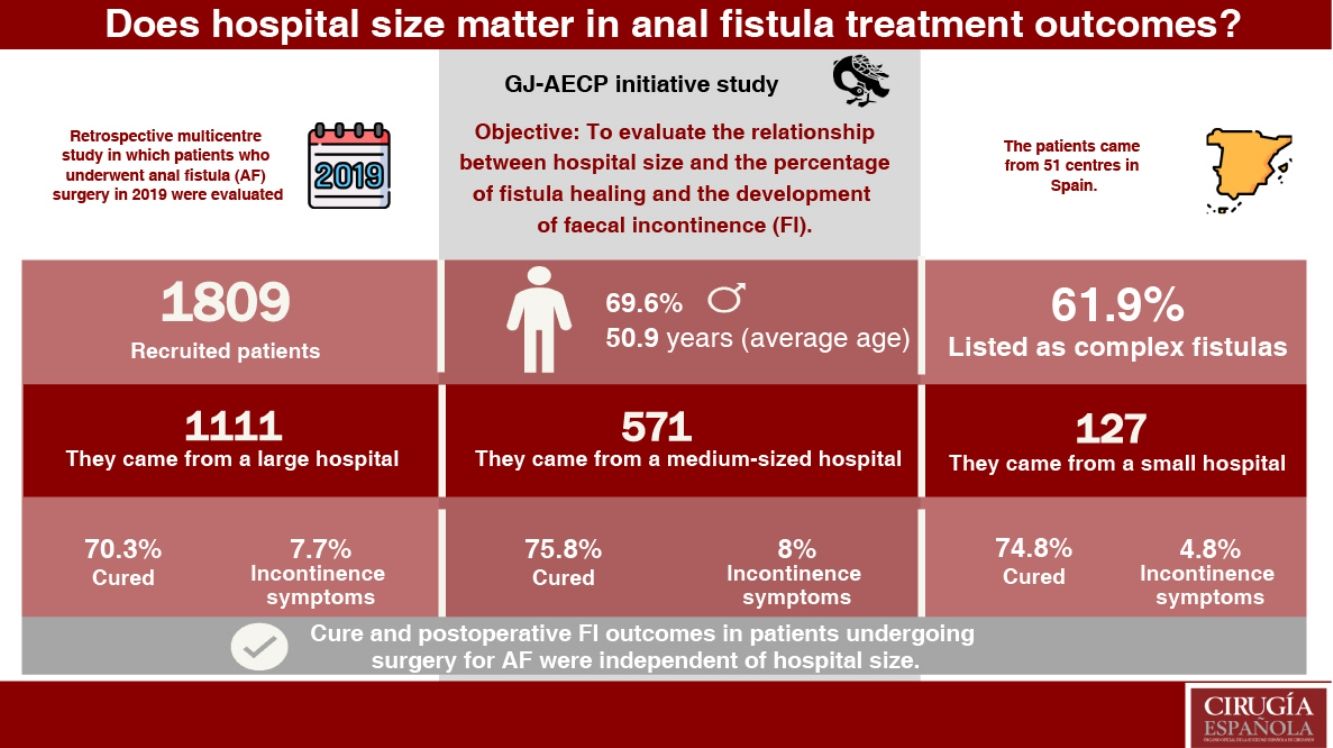

Results1809 patients were include. Surgery was performed in a low, middle, and high-volume hospitals in 127 (7.0%), 571 (31.6%) y 1111 (61.4%) patients respectively. After a mean follow-up of 18.9 months 72.3% (1303) patients were cured and 132 (7.6%) developed FI. The percentage of patients cured was 74.8%, 75.8% and 70.3% (p = 0.045) for low, middle, and high-volume hospitals. Regarding FI, no statistically significant differences were observed depending on the hospital volume (4.8%, 8.0% and 7.7% respectively, p = 0.473). Multivariate analysis didńt observe a relationship between AF cure and FI.

ConclusionCure and FI in patients who underwent AF surgery were independent from hospital volume.

En algunos procedimientos quirúrgicos se ha demostrado que la centralización en hospitales de alto volumen mejora los resultados obtenidos. Sin embargo, este punto aún no ha sido estudiado en los pacientes que son intervenidos por una fístula anal (FA).

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio multicéntrico retrospectivo en el que se incluyeron los pacientes operados de FA durante el año 2019 en 56 centros españoles. Se hizo un análisis uni y multivariante para analizar la relación entre el tamaño del lugar, el porcentaje de curación de la fístula y el desarrollo de incontinencia fecal (IF).

ResultadosSe incluyeron en el estudio a 1.809 pacientes. La cirugía se llevó a cabo en un hospital pequeño en 127 usuarios (7,0%), uno mediano en 571 (31,6%) y uno grande en 1.111 (61,4%). Tras un seguimiento medio de 18,9 meses, 72,3% de los participantes (1.303) se consideraron curados y 132 (7,6%) presentaron IF. El porcentaje de los rehabilitados de la FA fue de 74,8, 75,8 y 70,3% (p = 0,045) en los centros pequeño, mediano y grande, respectivamente. En cuanto a la IF no se evidenciaron diferencias significativas según el tipo de lugar (4,8, 8,0 y 7,7%, respectivamente, p = 0,473). En el análisis multivariante no se observó relación entre el tamaño del hospital y la curación de la fístula o el desarrollo de IF.

ConclusiónLos resultados de curación e IF posoperatoria en los pacientes sometidos a una cirugía por FA fueron independientes del volumen hospitalario.

Anal fistula (AF) surgery can have unsatisfactory results. The cure rate for operated AF could be around 80% for simple AF and 69% for complex AF.1 Regarding faecal incontinence (FI), it has been described that up to 10% of patients may suffer worsening of their anal continence, even in the treatment of simple AF.2

For some surgical pathologies, such as oesophageal or rectal cancer, performing surgery in high-volume centres has been shown to improve results.3–6 It might be thought that AF patients operated on in high-volume centres might have better outcomes than those operated on in smaller hospitals. However, no study has related the type of hospital and the results of AF treatment.

Recently, the young group of the Spanish Association of Coloproctology (GJ-AECP for its initials in Spanish) published a study that analyses the characteristics of patients operated on for AF in Spain, examining the risk factors that affect healing and postoperative FI.7 However, this study did not take into account the type of hospital in which the surgery was performed. For this reason, it was decided to review these data by analyzing the influence of hospital size on the outcomes of patients operated on for AF.

MethodsStudy designA retrospective, multicentre study organized by the GJ-AECP was conducted in which all Spanish hospitals were invited to participate. The cure rate was analysed 12 months after the intervention.

The inclusion criteria were patients over 18 years of age, with a diagnosis of anal fistula and undergoing elective surgery throughout 2019 (2020 was discarded due to the limitations caused by the pandemic). 2020 was considered the monitoring year; with a minimum follow-up of one year. Patients were included consecutively, except for those who did not meet the inclusion criteria. Patients with a doubtful diagnosis of AF or those who underwent an intervention without curative intent (placement of a drainage seton, drainage of abscesses, etc.) were excluded.

Variables analysedThe study variables analysed were:

- -

Demographic characteristics of the patients.

- -

AF characteristics and evolution of the condition.

- -

Pre and postoperative continence status.

- -

Diagnostic and surgical techniques employed.

- -

Follow-up made using medical history review or telephone call.

- -

Healing: disappearance of perianal suppuration after AF treatment one year after the intervention.

- -

Recurrence: disappearance of perianal suppuration for at least 6 months with its reappearance later.

- -

Persistence: perianal suppuration that did not disappear after AF surgery.

- -

Preoperative faecal incontinence: preoperative faecal incontinence: loss of voluntary control of the expulsion of gas or faeces for at least 3 months with an onset of symptoms 6 months before surgery. The Wexner Scale was used as a tool to evaluate the severity of faecal incontinence.

- -

Postoperative faecal incontinence: loss of voluntary control of the expulsion of gas or faeces for at least 8 weeks and that was not present before AF surgery.

- -

Preparatory surgery: all those interventions performed on patients with AF that are not intended to cure it, but rather to improve their condition for future curative surgery: drainage of collections, placement of setons…

The Parks et al.8 classification was used to analyse the type of AF. In addition, the classification into simple and complex fistulas described in various guidelines9–11was used:

- -

Simple anal fistula: superficial, intersphincteric or low transsphincteric fistula - (involvement of less than 30% of the external anal sphincter).

- -

Complex anal fistula: complex anal fistula: medium or high transsphincteric anal fistula (involvement of more than 30% of the external anal sphincter), suprasphincteric or extrasphincteric fistula, fistula with secondary tracts, abscesses or associated cavities, patients with IBD, at risk of IF (previous fistula in a woman, recurrent fistula) or with a previous diagnosis of IF.

The size of the hospitals was classified according to the number of beds in each centre according to the 2019 National Hospital Catalog12 as follows:

- -

Large hospital: area hospitals with 500 beds or more.

- -

Medium hospital: basic general hospitals, medium size with between 200 and 500 beds, limited technological resources, with some teaching weight.

- -

Small hospital: small regional hospitals, with less than 200 beds, hardly any high-tech equipment, few doctors and little complexity of care.

To analyse the accreditation of coloproctology units, the list of accredited centres of the Spanish Association of Coloproctology was used.13

The surgical techniques performed were grouped into fistulotomy, conventional sphincter-preserving techniques (advancement flap, ligation of the fistulous tract at the intersphincteric level (LIFT) and fistulotomy with sphincter repair) and minimally invasive sphincter-preserving techniques (laser fistula closure (FiLaC), stem cells, platelet-rich plasma, collagen paste, fibrin sealants, anal plug and video-assisted fistulous tract ablation (VAAFT)).

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed with Stata 13.1®. Categorical variables are presented as percentages and frequencies. Continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation.

The association between the collected variables and the target variables of the study was carried out using Pearson’s Chi square test, Fisher’s exact test or ANOVA test as appropriate. To analyse the relationship between cure and FI and hospital size, all those variables statistically related (p < 0.1) with the type of hospital in the univariate analysis were included in a logistic regression model to analyse the possible effect of confusion they could cause. An analysis of all possible models was carried out and the one with the lowest AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) was selected as the definitive model.

Differences were considered statistically significant if the p value was less than 0.05.

Ethical aspects and declaration of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and that no funding was required to carry out this work. All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical requirements of our institution, the ethical committee in question, and the 1964 Helsinki declaration with its subsequent modifications. This study was approved by the reference ethical committee (17/21-4609) and by the research committees of each of the participating centres.

ResultsA total of 1809 patients from 56 different centres were included in the study. The mean age was 50.9 (13.7) years and 69.6% (1248) of the patients were men. Of the patients included, 591 (34.1%), 189 (10.7%) and 502 (28.8%) were obese, diabetic or smokers respectively. Six point two per cent (112) of the patients had previously been diagnosed with IBD.

Surgery was performed in a small, medium and large hospital in 127 (7.0%), 571 (31.6%) and 1111 (61.4%) patients respectively. The coloproctology units in which these procedures were carried out had advanced accreditation in 746 cases (41.2%), basic in 65 (3.6%) and not accredited in 998 (55.2%).

Of the women included in the study, 226 (52.7%) had had at least one vaginal birth, with episiotomy being necessary in 100 (44.2%) and instrumentation in 39 (17.3%).

Of the total of patients, 794 (44.7%) had a history of previous proctological surgery, in 406 (22.6%) the fistula had recurred, having required previous interventions for this reason, and 55 (3.1%) reported preoperative FI.

The mean time of evolution of symptoms before surgery was 20.2 (31.2) months and 960 (54.0%) patients had undergone drainage of a perianal abscess before being diagnosed with AF.

In 707 (39.8%) patients no preparatory surgery was performed, but in 647 (36.5%), 239 (13.5%) and 182 (10.3%) 1, 2 and 3 or more preparatory surgeries were performed, respectively. An anal ultrasound was performed in 957 (53.9%) patients and an MRI in 480 (26.7%).

The type of anal fistula according to the Parks classification is shown in Table 1. In 220 (12.4%) patients there were multiple fistulous tracts and in 198 (11.1%) associated abscesses were observed. The location of AF was posterior in 856 (50.0%) patients, anterior in 538 (31.3%) and lateral in 326 (19.0%). The fistula was classified as simple in 679 (38.1%) patients and as complex in 1102 (61.9%).

| Mean num. | % Of standard deviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 50.9 years | 13,7 | |

| Sex (males) | 1248 | 69.6% | |

| Obesity | 591 | 34.1% | |

| Diabetes | 189 | 10.7% | |

| Smoker | 502 | 28.8% | |

| Type of hospital | Num. of centres | ||

| Small | 7 | 127 | 7.0% |

| Medium | 23 | 571 | 31.6% |

| Large | 26 | 1111 | 61.4% |

| Previous proctologic surgery | 794 | 44.7% | |

| Recurrent fistula | 406 | 22.6% | |

| Time of symptom evolution | 20.2 months | (31.2) | |

| Type of fistula | Superficial | 259 | 14.5% |

| Intersphincteric | 433 | 24.2% | |

| Transsphincteric | 1070 | 59.8% | |

| Low | 439 | 41.0% | |

| Medium | 451 | 42.1% | |

| High | 180 | 16.8% | |

| Suprasphincteric | 20 | 1.1% | |

| Extra lift | 8 | 0.5% | |

The surgical technique used is presented in Table 2. The most frequent was fistulotomy (1125, 68.0%) followed by conventional sphincter-preserving techniques (314, 19.0%) and minimally invasive sphincter-preserving techniques (216, 13.1%).

Surgical technique used for the treatment of anal fistula.

| Type of intervention | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Fistulotomy | 1125 | 62.3% |

| LIFT | 146 | 8.1% |

| FiLaC | 102 | 5.7% |

| Advancement flap | 99 | 5.5% |

| Drainage seton | 92 | 5.1% |

| Fistulotomy and sphincter reconstruction | 69 | 3.8% |

| Platelet rich plasma | 56 | 3.1% |

| Cutting seton | 46 | 2.6% |

| Fibrin sealant | 26 | 1.4% |

| Collagen paste | 16 | 0.9% |

| Plug | 9 | 0.5% |

| Stem cells | 6 | 0.3% |

| VAAFT | 1 | 0.1% |

| Others | 12 | 0.7% |

FiLaC: fistula laser closure; LIFT: ligation of the fistulous tract at the intersphincteric level; VAAFT: video-assisted ablation of the fistulous tract.

After a mean follow-up of 18.9 (11.0) months, 1303 (72.3%) patients were considered cured and 132 (7.6%) had new-onset postoperative incontinence.

Table 3 compares the characteristics of the patients according to the size of the hospital in which they were operated on, with no significant differences evident between the percentage of patients who presented a complex fistula but with significant differences in the type of fistula according to the Parks classification and in the surgical intervention performed.

| Small hospital | Medium hospital | Large hospital | p | Accredited hospital | Non-accredited hospital | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 127 | 571 | 1111 | 811 | 998 | ||

| Sex (n. % of men) | 94 (74.0%) | 396 (69.4%) | 758 (69.2%) | 0.533 | 562 (69.3%) | 686 (69.9%) | 0.797 |

| Age (years, standard deviation) | 52.7 (13.5) | 50.6 (13.6) | 50.8 (13.8) | 0.293 | 51.7 (13.9) | 50.2 (13.6) | 0.026 |

| Obesity (n, %) | 48 (37.8%) | 167 (32.0%) | 376 (34.8%) | 0.367 | 247 (32.4%) | 344 (35.5%) | 0.179 |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 20 (15.8%) | 59 (10.4%) | 110 (10.2%) | 0.153 | 87 (10.8%) | 102 (10.5%) | 0.856 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (n, %) | 3 (2.4%) | 34 (6.0%) | 75 (6.8%) | 0.146 | 58 (7.2%) | 54 (5.4%) | 0.129 |

| Previous proctological surgery (n, %) | 48 (39.0%) | 256 (44.8%) | 490 (45.2%) | 0.420 | 345 (42.5%) | 449 (46.5%) | 0.096 |

| Recurrent anal fistula (n, %) | 36 (28.6%) | 130 (23.1%) | 240 (21.6%) | 0.194 | 169 (20.9%) | 237 (23.9%) | 0.140 |

| Duration of symptoms (months, standard deviation) | 19.9 (19.6) | 17.4 (31.5) | 21.7 (32.1) | 0.026 | 21.6 (34.5) | 19.1 (28.2) | 0.102 |

| Perianal abscess (n, %) | 54 (42.5%) | 293 (51.5%) | 613 (56.7%) | 0.004 | 432 (53.4%) | 528 (54.5%) | 0.646 |

| Preparatory interventions | 0.029 | <0.001 | |||||

| None | 63 (49.6%) | 243 (43.6%) | 401 (36.8%) | 271 (34.5%) | 436 (44.1%) | ||

| One | 36 (28.4%) | 192 (34.4%) | 419 (38.4%) | 309 (39.3%) | 338 (34.2%) | ||

| 2 | 14 (11.0%) | 67 (12.0%) | 158 (14.5%) | 106 (13.5%) | 133 (13.5%) | ||

| Three or more | 14 (11.0%) | 56 (10.0%) | 112 (10.2%) | 100 (12.7%) | 82/8.3%) | ||

| Anal scan (n, %) | 61 (48.0%) | 291 (51.1%) | 605 (56.0%) | 0.062 | 523 (64.7%) | 434 (44.8%) | <0.001 |

| Magnetic resonance (n, %) | 21 (16.7%) | 181 (31.8%) | 278 (25.2%) | 0.001 | 174 (21.5%) | 306 (30.9%) | <0.001 |

| Complex fistula (n, %) | 73 (58.9%) | 342 (60.5%) | 687 (62.9%) | 0.495 | 517 (64.4%) | 585 (59.8%) | 0.048 |

| Multiple tracts (n, %) | 8 (6.3%) | 70 (12.3%) | 142 (13.1%) | 0.086 | 90 (11.2%) | 130 (13.4%) | 0.149 |

| Type of fistula (n, %) | <0.001 | 0.012 | |||||

| Superficial | 27 (22.3%) | 76 (13.4%) | 156 (14.1%) | 108 (13.5%) | 151 (15.3%) | ||

| Intersphincteric | 15 (12.4%) | 173 (30.6%) | 245 (22.2%) | 179 (22.3%) | 254 (25.7%) | ||

| Transphincteric | 76 (62.8%) | 309 (54.6%) | 685 (62.1%) | 508 (63.3%) | 562 (56.9%) | ||

| Supraesphincteric | 1 (.8%) | 7 (1.2%) | 12 (1.1%) | 8 (1.0%) | 12 (1.2%) | ||

| Extra lift | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (0.2%) | 5 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (0.8%) | ||

| Associated abscess. %) | 18 (14.2%) | 77 (13.6%) | 103 (9.5%) | 0.024 | 69 (8.5%) | 129 (13.3%) | 0.001 |

| Surgical technique (n, %) | <0.001 | 0.650 | |||||

| Fistulotomy | 83 (72.2%) | 371 (73.0%) | 671 (65.0%) | 497 (66.8%) | 628 (68.9%) | ||

| SPT | 8 (7.0%) | 114 (22.4%) | 192 (18.6%) | 146 (19.6%) | 168 (18.4%) | ||

| MISPT | 24 (20.9%) | 23 (4.5%) | 169 (16.4%) | 101 (13.6%) | 115 (12.6%) |

MISPT: minimally invasive sphincter-preserving technique; SPT: sphincter-preserving technique.

Table 4 analyses the number and percentage of each of the most relevant surgical techniques according to the type of hospital.

Number and percentage of patients subjected to the most relevant techniques according to the type of hospital.

| Type of intervention | Small hospital (n, %) | Medium hospital (n, %) | Large hospital (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fistulotomy | 83 (65.4%) | 371 (65.1%) | 671 (60.6%) |

| LIFT | 4 (3.2%) | 43 (7.5%) | 99 (8.9%) |

| FiLaC | 15 (11.8%) | 14 (2.5%) | 73 (6.6%) |

| Advancement flap | 0 (0%) | 36 (6.3%) | 63 (5.7%) |

| Drainage seton | 10 (7.9%) | 39 (6.8%) | 43 (3.9%) |

| Fistulotomy and sphincter reconstruction | 4 (3.2%) | 35 (6.1%) | 30 (2.7%) |

| Platelet rich plasma | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 56 (5.1%) |

| Fibrin sealant | 9 (7.1%) | 2 (0.4%) | 15 (1.4%) |

FiLaC: fistula laser closure; LIFT: ligation of the fistula tract at the intersphincteric level.

The percentage of patients in whom AF cure was achieved was 74.8%, 75.8% and 70.3% (p = 0.045) in the small, medium and large hospitals respectively. Regarding new-onset FI after surgery, no significant differences were found depending on the type of hospital in which the intervention was performed (4.8%, 8.0% and 7.7% respectively, p = 0.473).

Regarding the relationship between the percentage of patients cured of AF and the accreditation or not of the coloproctology unit, it was observed that in the non-accredited centres the percentage of patients cured was 72.0% (714), while in accredited centres this percentage was 72.8% (589) (p = 0.695). No differences were found in the appearance of postoperative FI: 80 (8.5%) in non-accredited centres vs. 52 (6.6%) in accredited centres, p = 0.146.

In the multivariate analysis, the number of preparatory interventions, the presence of multiple tracts, the type of fistula according to the Parks classification and the type of surgical technique performed were a confounding factor in the relationship between AF cure and hospital size. In the logistic regression adjusted for these confounding variables, hospital size had no relationship with AF cure (OR for small hospital 1.4, 95% Confidence Interval 0.8–2.4, p = 0.243 and OR for medium hospital 1.1, 95% Confidence Interval 0.8–1.5, p = 0.410). In the case of postoperative FI, the confounding factors included in the final model were the number of preparatory interventions and the type of technique performed. In the model adjusted for these variables, the FI was also not related to the size of the hospital (OR for small hospital 1.5, 95% Confidence Interval 0.6–3.7, p = 0.358 and OR for large hospital 1, 5, 95% Confidence Interval 0.6–3.5, p = 0.371)

DiscussionIn the multivariate analysis, no relationship was observed between the cure rate or postoperative FI and the size of the hospital or its accreditation. However, differences were observed in that patients operated on in medium and large hospitals had more previous perianal abscesses, a greater number of fistulous tracts and more patients had preparatory surgeries before the intervention. Small hospitals performed fewer preoperative tests and had more patients with superficial fistulas. Regarding the surgical technique, in small hospitals, more minimally invasive techniques were performed such as Laser Fistula Closure (FiLaC) or the use of fibrin sealants. Meanwhile, in medium and large hospitals, more complex surgeries such as advancement flap or intersphincteric fistulous tract ligation (LIFT) were performed.

There are complex pathologies, such as oesophageal and rectal cancer, in which it has been shown that the centralisation of the processes achieves an improvement in the results obtained.3–6 However, this has not been studied to date in patients with AF; this is the first study that has analysed the relationship between the characteristics of the centre where the patient is operated on (volume and degree of accreditation) and the outcomes obtained. It might be thought that AF surgery is a simple surgery that can be performed in any centre. However, AF surgery can be one of the most complex interventions that a colorectal surgeon must face, and may even require a diversion stoma.14 Therefore, there must be other factors that explain why the outcomes of operated AF patients are independent of centre volume. One of the explanations would be that the majority of fistulas are simple AF and that only a small percentage are truly complex. The challenge would be to look for markers that identify which fistulas are really complicated to treat and should be referred to reference centres. Another explanation could be that the most complex patients are concentrated in referral centres and we have not been able to identify them because the definition of complex fistula is too broad. It must also be taken into account that AF is a common pathology, so it is possible that even in small centres the experience in the treatment of these patients is sufficient to provide an adequate treatment and only a small percentage of patients with highly complex AF really need to be referred.

It is important to note that there are many different surgical techniques for the treatment of patients with AF and that currently none of them can be recommended as the technique with the most optimal outcomes.15 Instead, the most appropriate technique for the particular patient must be selected depending on many factors, such as the experience of each surgeon with each technique. For this reason, it is possible that less technically demanding procedures are chosen in centres with less experience, while more complicated interventions are used in high-volume centres. In our study we observed that in small centres simpler techniques were used (laser or fibrin sealants) while in medium and large centres more complex techniques were selected (advancement flap or LIFT).

In the analysis of the type of hospital accreditation, it was also observed that neither the cure of AF nor the appearance of FI depended on the accreditation of the unit.

From the results obtained in this study, it does not seem necessary to centralise the treatment of patients with AF, although it seems reasonable to select those patients with complex AF to be evaluated in high-volume centres with accredited units.

One limitation of this study is that it was a retrospective, multicentre study with losses in data collection. Furthermore, the centres joined the study voluntarily, so it is possible that the small hospitals that were included represent those centres with a special interest in colorectal surgery. On the other hand, not having determined the number of fistulas treated by each surgeon could affect the final outlook of the study since there may be surgeons in small hospitals with a high volume of patients and vice versa, causing these data to fail to be completely representative.

The positive points of this study would be the large sample size, the large number of centres included and the use of precise definitions.

In conclusion, in our study, healing and postoperative FI in patients undergoing surgery for AF did not have a clear relationship with hospital volume, being similar in small, medium and large hospitals. Further studies are required to continue studying this possible relationship.

Conflicts of interestThere were no conflicts of interest in the completion of this work. This is non-commercial clinical research promoted by individual researchers.

FundingThe researchers will not receive any financial compensation for their participation.

Dr. Javier Espinosa Soria, Dr. Jordi Seguí Orejuela, Hospital de Elda (Alicante); Dra. Natalia Gutiérrez Corral, Hospital Universitario de San Agustín (Avilés); Dra. María Carmona Agundez, Hospital Universitario de Badajoz (Badajoz); Dr. David Saavedra Pérez, Dra. Helga Calvaienen Mejía, Hospital Consorci Sanitari Alt Penedes-Garraf (Barcelona); Dra. Marta Barros Segura, Dr. Gianluca Pellino, Hospital Vall d’Hebron (Barcelona); Dr. Gerardo Rodríguez León, Hospital de Viladecans (Barcelona); Dra. Andrea Jiménez Salido, Hospital Comarcal Alt Penedés (Vilafranca del Penedés); Dra. Tatiana Gómez Sánchez, Dra. Susana Roldán Ortiz, Hospital Puerta del Mar (Cádiz); Dr. Luis Eloy Cantero Gutiérrez, Hospital Comarcal Sierrallana (Torrelavega); Dra. Natalia Suarez Pazos, Dra. Lidia Cristóbal Poch, Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla (Santander); Dr. Juan Ramón Gómez López, Hospital Medina del Campo (Medina del Campo – Valladolid); Dr. Pablo Méndez Sánchez, Hospital General de Valdepeñas (Valdepeñas – Ciudad Real); Dra. Pilar Fernández Veiga, Dra. Victoria Erene Flores Rodríguez, Dr. Oscar Cano Valderrama, Dr. Enrique Moncada Iribarren, Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro (Vigo, Pontevedra); Dra. Nuria Ortega Torrecilla, Hospital Josep Trueta (Girona); Dr. Alberto Carrillo Acosta, Dra. Cristina Plata Illescas, Dr. Jose Luis Diez Vigil, Hospital Virgen de las Nievas (Granada); Dra. Estefanía Laviano Martínez, Fundación Hospital Calahorra (Calahorra- La Rioja); Dra. María Beltrán Martos, Hospital de León (León); Dr. David Ambrona Zafra, Dra. Silvia Pérez Farré; Hospital Arnau de Vilanova (Lleida); Dr. David Díaz Pérez, Dra. Ana Belén Gallardo Herrera (Hospital de Torrejón (Torrejón de Ardoz – Madrid); Dra. Elena Viejo, Hospital Infanta Leonor (Madrid); Dr. Juan Ocaña Jiménez, Dr. Jordi Núñez Núñez, Hospital Ramón y Cajal (Madrid); DRa. Alba Correa Bonito, Hospital Fundación Alcorcón (Madrid); Dra. Elena Bermejo Marcos, Hospital de la Princesa (Madrid); Dra. Marta González Bocanegra, Dra. Alicia Ferrer Martínez, Hospital de Getafe (Madrid); Dra. Irene Mirón Fernández, Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga (Málaga); Dra. Elena González Sánchez-Migallón, Dra. María Teresa Solano Palao, Hospital Rafael Méndez de Lorca (Murcia); Dr. Emilio Peña Ros, Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía (Murcia); Dra. Inés Aldrey Cao, Hospital de Ourense (Ourense); Dra. Carlenny Suero Rodríguez, Dra. Victoria Maderuelo, Complejo Asistencial de Palencia (Palencia); Dra. Aroa Abascal Amo, Hospital de Segovia (Segovia); Dr. Juan Cintas Catena, Hospital Vírgen de la Macarena (Sevilla); Dra. María del Campo La Villa, Hospital Santa Bárbara (Soria); Dra. Mahur Esmaili Ramo, Dr. Javier Broeckhuizen Benítez, Hospital Nuestra Señora de Prado (Talavera de la Reina); Dra. Ana Navarro Barles, Hospital de San Joan de Reus (Tarragona); Dr. Luis Eduardo Pérez Sánchez, Dra. Ana Soto Sánchez, Dra. Nélida Díaz Jiménez, Dra. Ana María Feria González, Hospital Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria (Tenerife); Dra. Estefanía Domenech Pina, Dr. Alejandro Ros Comesaña, Hospital de Torrevieja (Torrevieja); Dra. Zutoia Balciscueta Coltell, Hospital Arnau de Vilanova (Valencia); Dra. Leticia Pérez Santiago, Dra. Luisa Paola Garzón Hernández, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia (Valencia); Dra. Alejandra de Andrés Gómez, Dr. Antonio Melero Abellán, Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia (Valencia); Dr. Jorge Sancho Muriel, Dra. Mónica Millán Scheiding, Dra. Hanna Cholewa, Hospital de La Fé (Valencia); Da. Marina Alarcón Iranzo, Hospital de Sagunto (Valencia); Dra. Ana FluixáPelegri, Hospital Francesc de Borja (Gandía); Dra. Tamara Fernández Miguel, Dra. Natalia Ortega Machón, Hospital Galdakao Usansolo (Bilbao); Dra. Natalia Alonso Hernández, Dr. Álvaro García Granero, Hospital Son Espases (Palma de Mallorca); Dra. Tatiana Civeira Taboada, Dr. Yago Rojo Fernández, Hospital Universitario de la Coruña (Coruña); Dr. Jose Aurelio Navas Cuellar, Hospital Universitario de Valme (Sevilla); Dra. Celia Castillo, Dra. Isabel Pascual Miguelañez, Hospital Universitario de la Paz (Madrid); Dra. Sandra Dios Barbeitio, Dra. María Luisa Reyes Díaz, Dra. Ana María García Cabrera, Dra. Irene María Ramallo Solís, Hospital Virgen del Rocío (Sevilla); Dra. Teresa Pérez Pérez, Hospital de Xátiva (Valencia); Dr. Gabriel Marín, Hospital Reina Sofía (Tudela- Navarra); Dra. Aranzazu Calero Lillo, Fundaciò Hospital Sperit Sant (Barcelona); Dr. Luis Sánchez Guillén, Dra. Julia López Noguera, Dr. Miguel Ángel Pérez, Hospital General Universitario de Elche (Elche- Alicante).