Early hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT) after liver transplantation (LT) is a serious complication associated with a postoperative morbidity rate of 3%–7% and risk of graft loss.1 Occasionally, thrombosis is exclusive to one of the branches of the hepatic artery and results in necrosis limited to one lobe or several segments. In these cases, resection of the affected parenchyma has proven to be an alternative with good long-term results. The development of laparoscopic surgery has allowed efficient resolution of early complications associated with liver transplantation.2 We present the first case, to our knowledge, of a laparoscopic extended left lateral sectionectomy in the early postoperative period in a patient with LT.

A 69-year-old man with a history of hepatorenal transplant in 2017. In 2020, he started with cholestasis, was diagnosed with ischaemic cholangiopathy and was included in the transplant waiting list. The graft came from a brain death donation from a 55-year-old woman with a normal liver biopsy (total warm ischaemia time of 17 min and cold ischaemia time of 396 min). The left hepatic artery originated from the left gastric artery coming directly from the aorta. In bench surgery, the left hepatic artery was anastomosed to the splenic artery and, in transplantation, the recipient's splenic artery was anastomosed to the donor's celiac trunk patch. On the second postoperative day, in the control ultrasound, there was no flow in the left hepatic artery, confirmed by computed tomography angiography, with no relevant clinical or analytical repercussions, so a non-invasive approach and treatment with heparin at anticoagulant doses was decided.

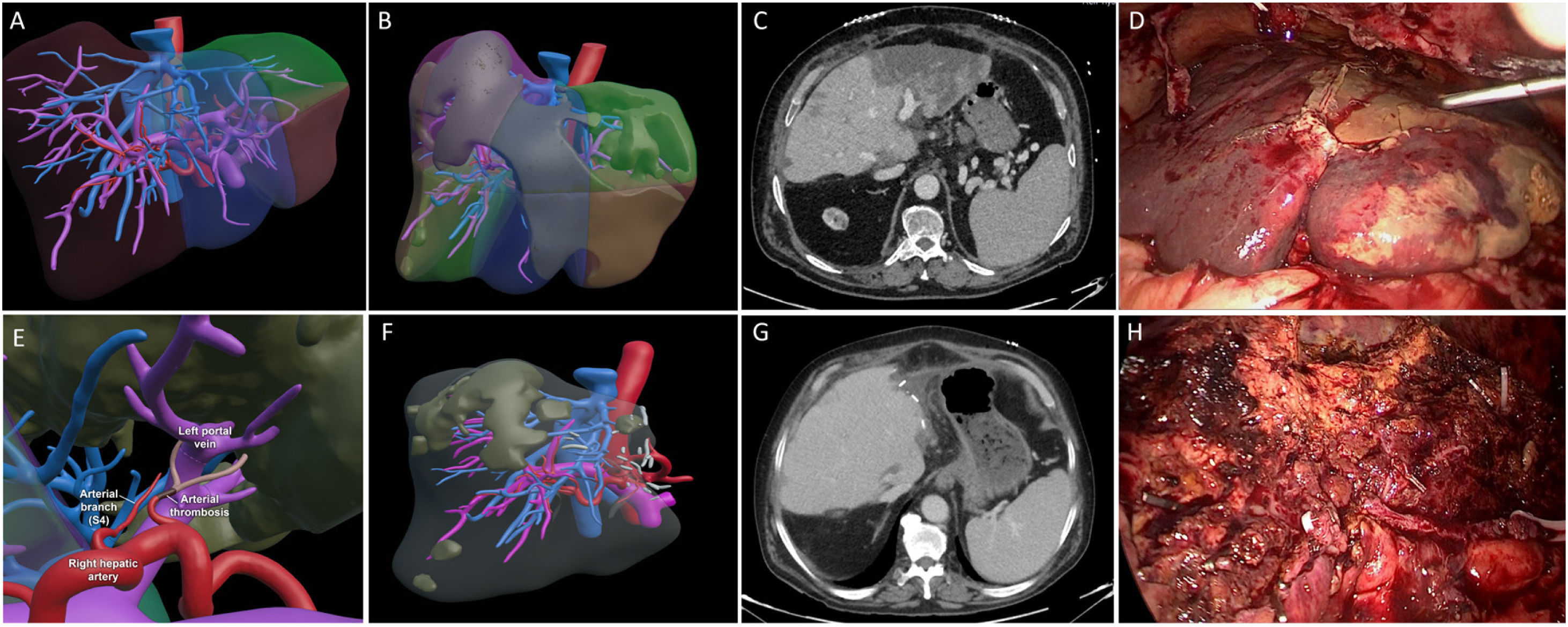

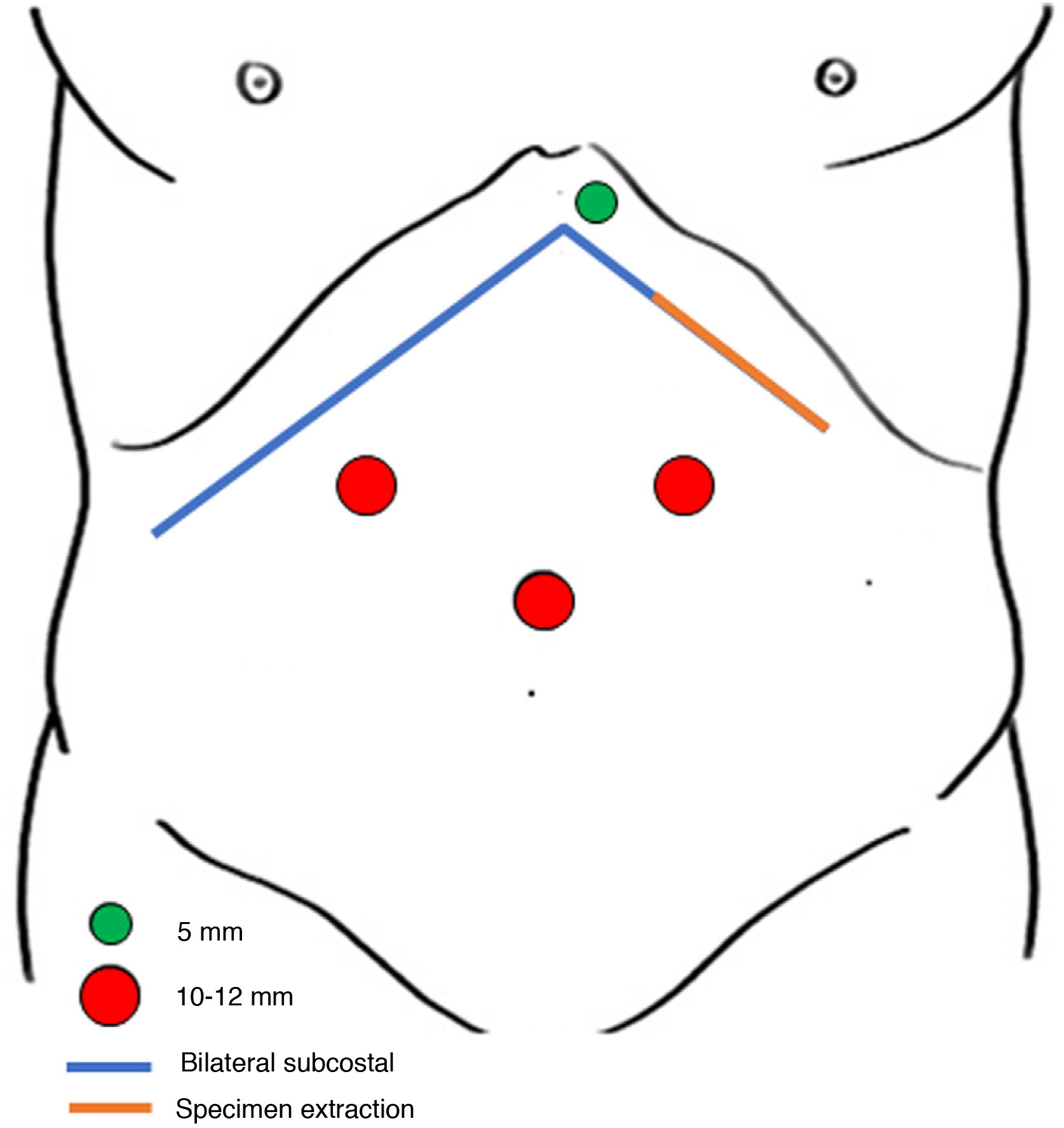

On the eighth day, he developed fever and blood tests revealed mainly worsening leukocytes (3.20 × 103/L), C-reactive protein (12.10 mg/L), -glutamyl transpeptidase (422 U/L) and prothrombin activity (54%). A new CT scan was performed and reported ischaemia of the left hepatic lobe more marked in segments 2–3 with signs of hepatic necrosis and extension to part of segment 4 (Fig. 1A–E). On the twelfth postoperative day, in view of these findings, a laparoscopic hepatectomy was planned. We used the lithotomy position ("French" position) and the surgeon was positioned between the legs. We placed 4 trocars: one supraumbilical (10 mm), 2 in the right and left upper quadrant (10 and 12 mm respectively) and one in the epigastric area (5 mm) (Fig. 2). On insertion of the camera, there was an abscess in the left subhepatic space which was drained. The left lateral sector was completely necrotic. We performed a pure laparoscopic extended left lateral sectioning on demand of the ischaemic area of 4a-b to a depth with viable and well perfused tissue (Fig. 1F–H). During hepatectomy, Pringle's manoeuvre was not prepared due to the risk of portal vein and hepatic artery damage in early postoperative LT. The operative time was 210 min and blood losses were 300 ml. without the need for transfusions. The hepatectomy specimen was removed through an incision in the left lateral region of the bilateral subcostal incision. Blood culture was positive for Enterococcus faecium. There were no postoperative complications. The patient was discharged on the fifth postoperative day. After 9 months of follow-up the patient had no complications.

Preoperative surgical planning of 3D virtual reconstruction (A). 3D virtual reconstruction of liver ischaemia (B). CT scan after liver transplantation with ischaemia of the left hepatic lobe and signs of necrosis in segments 2–3 (C). Intraoperative findings (D). 3D virtual reconstruction of thrombosis of the left hepatic artery and branch of section 4 (E). 3D virtual reconstruction of the graft after laparoscopic liver resection (F). CT scan on postoperative day 5 after laparoscopic liver resection. The graft is adequately perfused with a small region of hypoperfusion in the vicinity of the resection margin (G). Intraoperative findings of the liver graft after laparoscopic hepatectomy (H).

The management of early HAT is directly related to its clinical situation and the location of the thrombosis. Endovascular or surgical revascularisation is often the first-line treatment for patients with HAT as it can reduce the risk of graft loss.3 The success of the endoluminal approach in achieving definitive restoration of arterial flow is very limited if arterial anatomical defects are not resolved.4 Among the therapeutic management options for early thrombosis, the option of not performing immediate revascularisation can be selected.5 This non-invasive approach often avoids the need for further transplantation, but the development of biliary or infectious complications is not uncommon. In these situations, endoscopic and radiological approaches may be insufficient, with liver resection being the most recommended option when there is delimited hepatic necrosis, as in this patient. Sommacale et al.6 reviewed a series of liver resections in LT patients, describing a total of 6 cases of segmental HAT that underwent hepatectomy by open surgery with a high rate of associated morbidity.

In recent years there has been a great deal of standardisation of laparoscopic liver surgery.7 There is evidence in the literature that surgery via a laparoscopic approach involves less surgical aggression than the open approach and is associated with less immune system depression, shorter hospital stays and faster functional recovery. Therefore, it appears that LT patients may be optimal candidates for this approach.2,8,9 In cases where liver resection is necessary postoperatively after LT, the ischaemia caused by thrombosis facilitates the resection plane, avoiding the need for the Pringle manoeuvre, which would be inadvisable due to the risk of damage to the bile duct and alteration of blood flow due to the short time that has elapsed since transplantation.

Laparoscopic liver resection in the early postoperative period after transplantation may be an appropriate indication in selected patients. The immunological, morbidity and recovery advantages associated with this approach favour its performance in newly transplanted patients, especially in favourable liver segments.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.