The development of new techniques such as natural orifice surgery seeks to improve clinical and aesthetic results in different fields. It has been successfully used to performed procedures such as appendectomies, cholecystectomies, and oncologic colon resections.1 Nevertheless, there are few published reports about the use of this approach in the management of ventral hernias.2,3

We present the case of a 58-year-old woman with hypothyroidism, 2 vaginal deliveries and surgery for epigastric hernia who consulted for pain and a mass along the scar of the previous surgery. Abdominal examination discovered a recurrent hernia, which was reductible, along with an aponeurotic defect measuring 4cm in diameter. We proceeded with the repair using a hybrid transvaginal approach, starting with the preoperative administration of 2g of amoxicillin-clavulanate and perineal/vaginal lavage of diluted povidone-iodine solution.

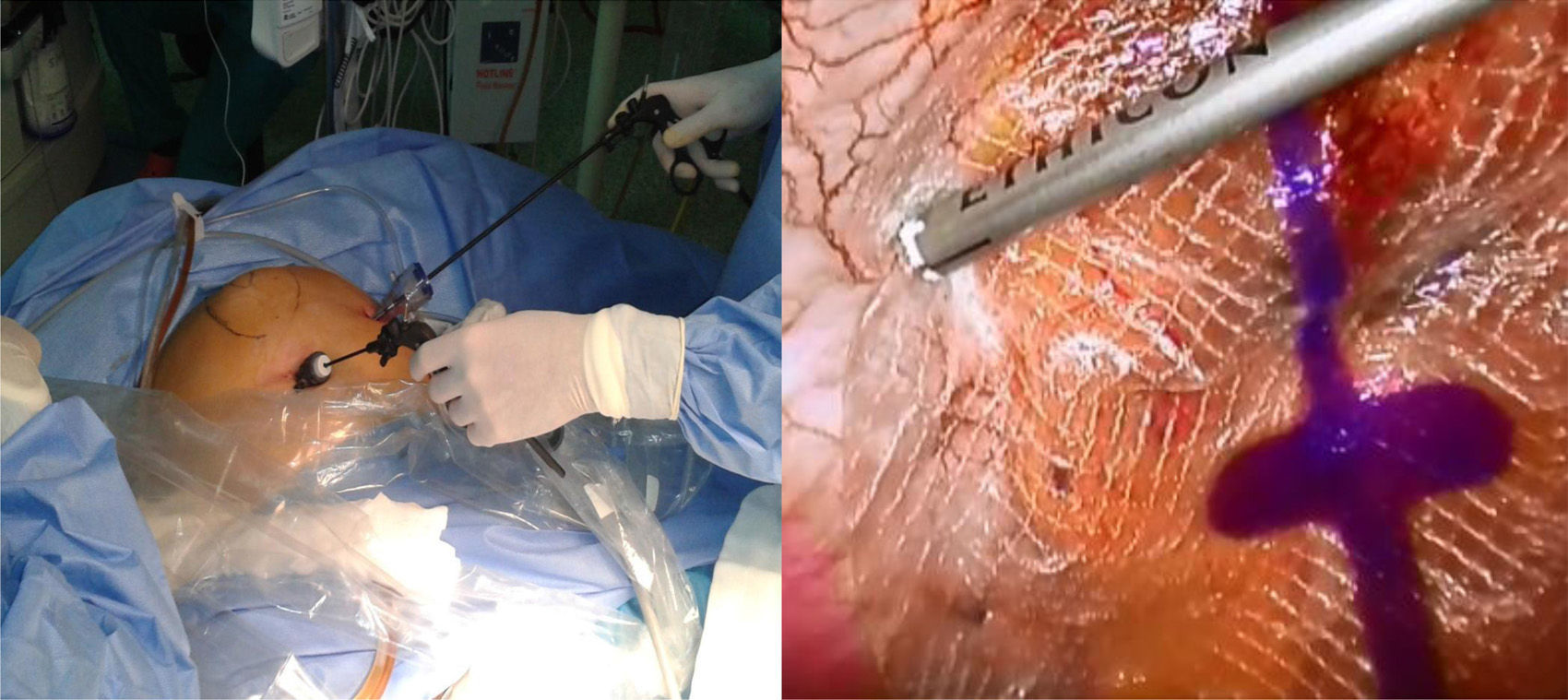

With the patient in the modified Lloyd-Davies position, the surgeon stood on the left and the assistant surgeon stood between the patient's legs. Pneumoperitoneum was created with a transumbilical Veress needle, and then a 5-mm trocar was inserted in the left flank for the later use of forceps and the stapler to attach the prosthesis. Through the orifice of the Veress needle, a 3-mm trocar was introduced to provide access for mini-instruments (Fig. 1).

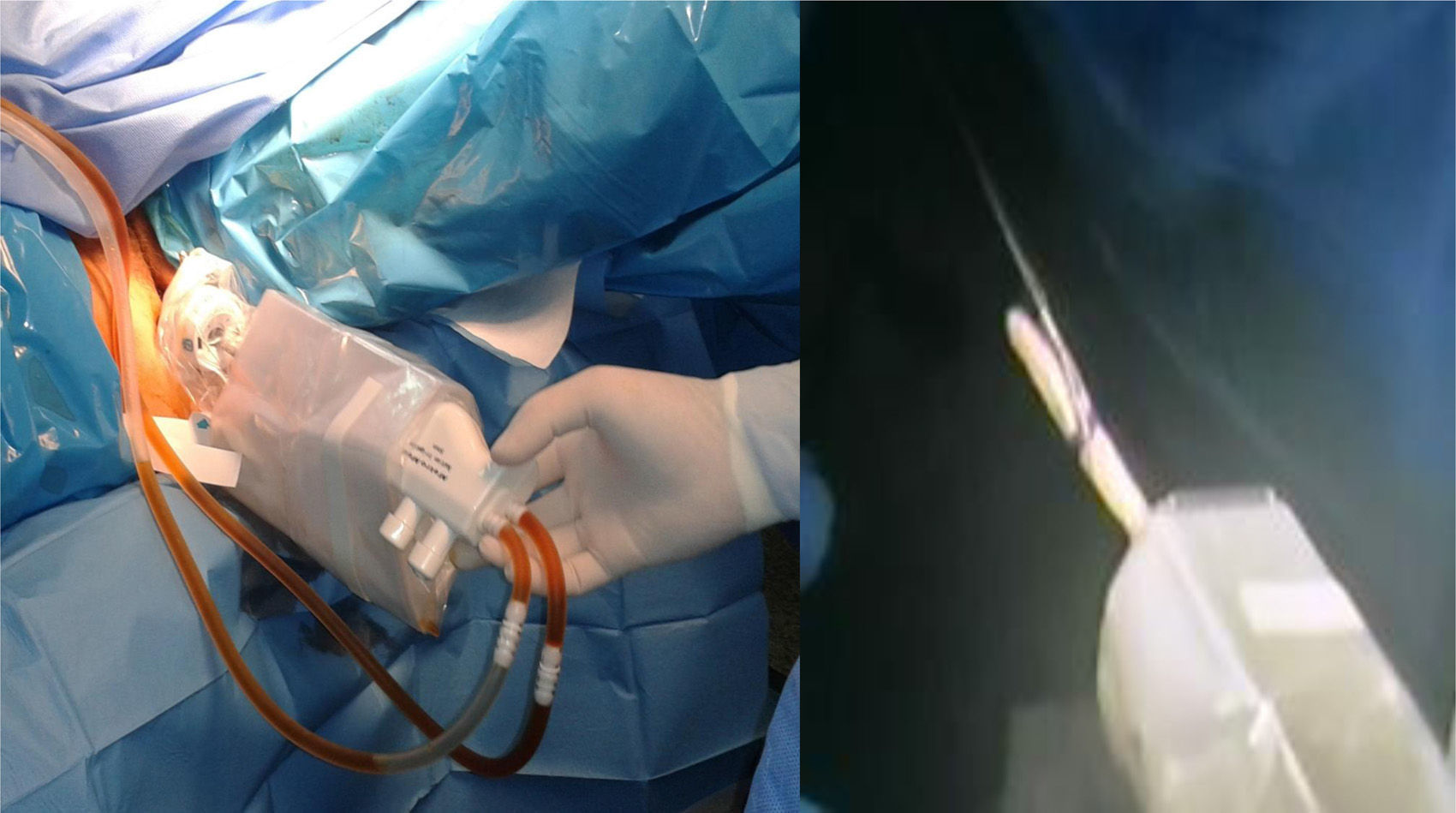

The patient was placed in forced Trendelenburg position. With the laparoscope (5mm 0° optics, through the 5-mm port) an extra-long optical trocar (150mm) was inserted through the posterior vaginal fornix (12mm EndoPath® Xcel™), which we later used to insert the mesh and optics (10mm and 30°). The transvaginal trocar was protected with a sterile plastic sheath and the pouch of Douglas was washed with a povidone-iodine solution (Fig. 2). After releasing the omental adhesions of the hernia sac using the 2 abdominal ports as working channels and the transvaginal trocar to insert the 30° optic, we proceeded with the mesh placement (Ethicon Physiomesh™ Flexible Composite Mesh). The patch was rolled up for insertion through the vaginal trocar without any further protection and subsequently fixed with 2 crowns of absorbable straps (Ethicon Securestrap™ 5mm Absorbable Strap Fixation Device) (Fig. 1). Afterwards, the 3 and 10mm trocars were removed under direct vision (5mm 0° optic through the trocar of the left flank) and the vaginal opening was closed vaginally with 2 polyglactin sutures (9102/0) and the abdominal skin with monofilament (3/0). The patient had a favourable postoperative course and was discharged from the hospital 36h after surgery and continued to be asymptomatic one month later.

The benefits of the laparoscopic approach in the treatment of ventral and abdominal wall hernias have been demonstrated in several studies, including lower risk of wound infection and shorter hospital stay, with recurrence rates that are lower than open surgery in many reports.4 Furthermore, in order to minimize parietal aggression, mini-instruments have been developed, which allow for dissecting, resecting and manipulating different structures within the abdominal cavity through minimal 2–3mm incisions with accuracy and safety. The transvaginal approach aims to avoid abdominal incisions and provide aesthetic, pain-related and structural benefits.5

Thus, the combination of the benefits of these treatment approaches for abdominal wall disease is the basis for the development of the technique described. It avoids having to make an abdominal incision for placement of the 10–12mm trocar usually used for the placement of the mesh and stitches, if necessary, with the potential risk for recurrent incisional hernia of 1%–6% according to the literature.6,7 Other groups have proposed inserting this 10–12mm trocar through the aponeurotic hernia defect itself while using other 5mm ports,8 thus avoiding the creation of another fascial defect.

Although septic complications associated with the transvaginal approach are rare (less than 1%),9 to prevent possible intraabdominal and mesh contamination from being introduced through the transvaginal trocar, we applied the following measures: preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis, use of a sterile sheath for the entry of the transvaginal trocar in the perineum, change of gloves before handling the prosthesis and lavages of the pouch of Douglas through the transvaginal trocar with a povidone-iodine solution diluted to 20%. Other complications associated with the transvaginal approach are mild and uncommon, such as bleeding or local pain. A period of sexual abstinence is recommended for 2–3 weeks.

We believe that the technique we present is simple, safe and reproducible. It is a valid option in selected cases of women with no history of pelvic surgery or gynaecological problems (pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, etc.) with umbilical hernias and aponeurotic defects smaller than 8cm without contraindication for laparoscopic repair. The use of flexible endoscopes with the transvaginal access may also be useful for improving visualization at distant points of the pelvis and lateral wall of the abdomen.10

Please cite this article as: Bruna M, Noguera J, Martínez I, Oviedo M. Eventroplastia transvaginal híbrida. Cir Esp. 2013;91:539–541.