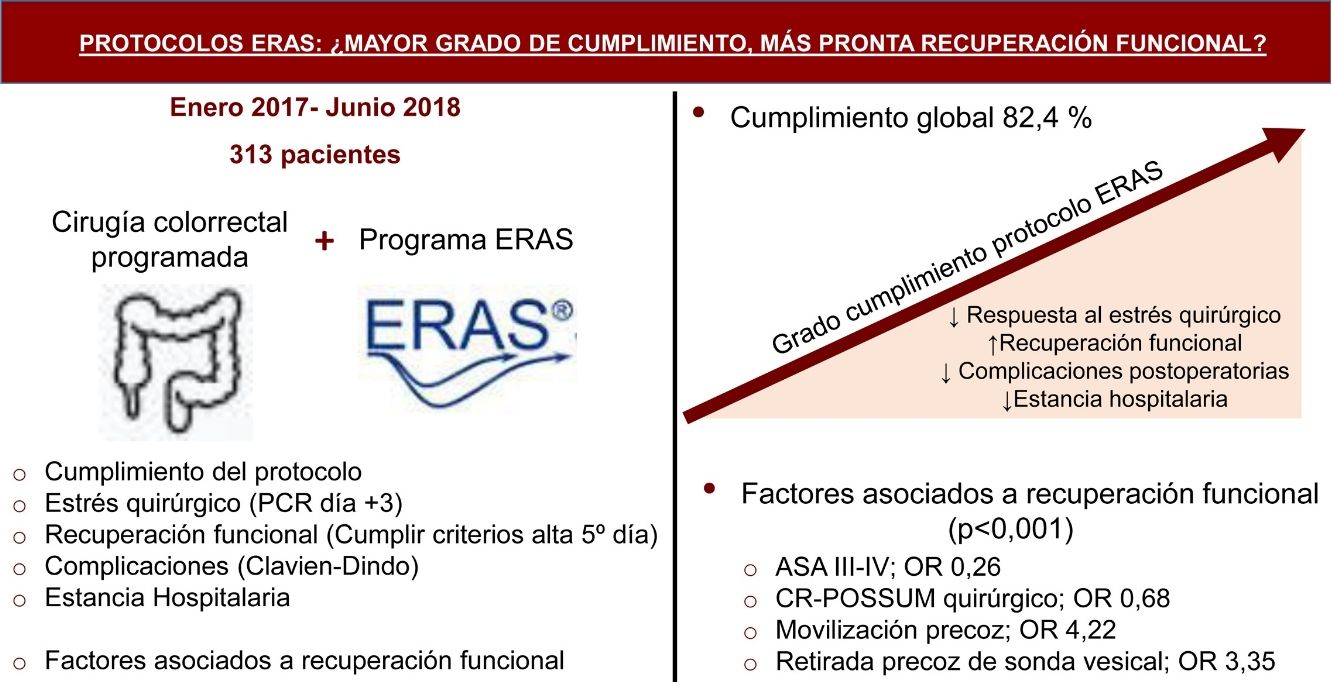

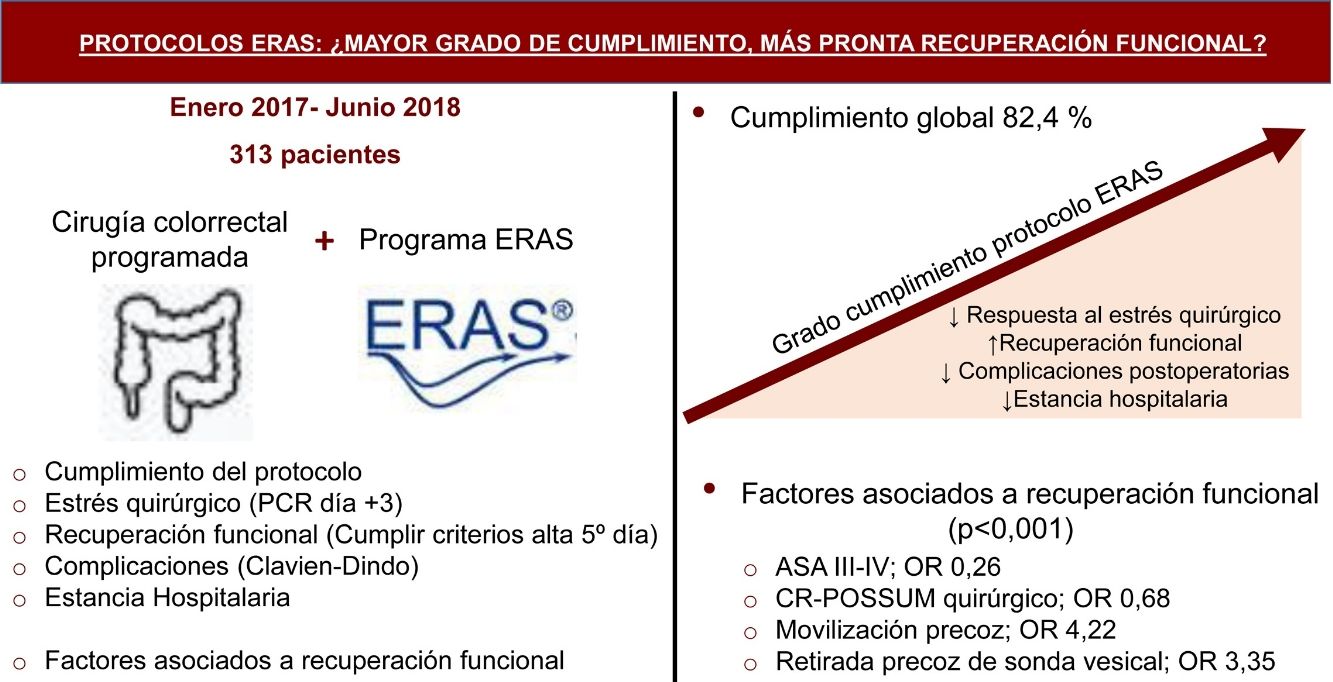

Compliance to ERAS protocols is a process quality measure that is associated with better outcomes. The main objective of this study is to analyze the association between protocol compliance, surgical stress and functional recovery. The secondary objective is to identify independent factors associated with functional recovery.

MethodsA prospective observational single-center study was performed. Patients who had scheduled colorectal surgery within an ERAS program from January 2017 to June 2018 were included. We analyzed the relationship between protocol compliance percentage and surgical stress (defined by C-reactive protein [CRP] blood levels on postoperative 3rd day), and functional recovery (defined by the proportion of patients who met the discharge criteria on the 5th PO day or before). Multivariate analysis was performed to assess independent factors associated with functional recovery.

Results313 patients were included. For every additional percentage point of compliance to the protocol 3rd day, C-reactive protein plasma level decreased 1.46 mg/dL and the probability to meet the discharge criteria increased 7% (P < .001 both). Independent factors associated with functional recovery were ASA III-IV (OR 0.26; 0.14−0.48), surgical CR-POSSUM score (OR 0.68; 0.57−0.83), early mobilization (OR 4.22; 1.43−12.4) and removal of urinary catheter (OR 3.35; 1.79−6.27), P < .001 each.

ConclusionBetter compliance with ERAS protocol in colorectal surgery decreases surgical stress and accelerates functional recovery.

El grado de cumplimiento de los protocolos de Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) es una medida de calidad del proceso, que además se asocia a mejores resultados. El objetivo del presente estudio es analizar la relación existente entre el grado de cumplimiento del protocolo, el estrés quirúrgico y la recuperación funcional. Se plantea como objetivo secundario, la identificación de factores independientes asociados a la recuperación funcional.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo observacional unicéntrico de pacientes sometidos a cirugía colorrectal programada dentro de un programa ERAS entre enero de 2017 y junio de 2018. Se analizó el grado de cumplimiento del protocolo porcentual y su relación con el estrés quirúrgico (definido por los niveles plasmáticos de proteína C reactiva al tercer día), y la recuperación funcional (definida por el cumplimiento de los criterios de alta el quinto día postoperatorio o antes). Se llevó a cabo un análisis multivariante de factores independientes asociados a recuperación funcional.

ResultadosSe analizaron 313 pacientes. Por cada punto porcentual de cumplimiento adicional del protocolo disminuye 1,46 mg/dL la proteína C reactiva del tercer día y aumenta un 7% la probabilidad de cumplir criterios de alta (p < 00,1 ambos). Los factores asociados a recuperación funcional fueron ASA III-IV (OR 0,26; 0,14-0,48), puntuación CR-POSSUM quirúrgico (OR 0,68; 0,57-0,83), movilización precoz (OR 4,22; 1,43-12,4) y retirada precoz de sonda vesical (OR 3,35; 1,79-6,27), todos ellos p < 0,001.

ConclusiónEl aumento del grado de cumplimiento del protocolo ERAS en cirugía colorrectal, disminuye el estrés quirúrgico y acelera la recuperación funcional.

ERAS programs incorporate a series of evidence-based strategies aimed at reducing the stress triggered by surgery and increasing functional recovery. This implies a reduction in postoperative complications and hospital stay, which thereby reduces healthcare costs.1–3

It is necessary to monitor the degree of compliance with the different strategies, not only to assess their quality and identify points for improvement, but because the degree of compliance with the program influences the results.2

The impact of the degree of compliance with the programs on hospital stay and postoperative complications has been widely studied.1,3,4 However, few studies have analyzed the impact on surgical stress and functional recovery in an isolated manner.4–6 This is the first study to analyze the impact of the degree of compliance on both surgical stress and functional recovery.

The secondary objective is to identify the independent factors associated with functional recovery.

MethodsStudy design. Patients who underwent elective colorectal surgery from January 2017 to June 2018 were retrospectively identified within a prospective database at a single institution, the Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro de Majadahonda (HUPHM).

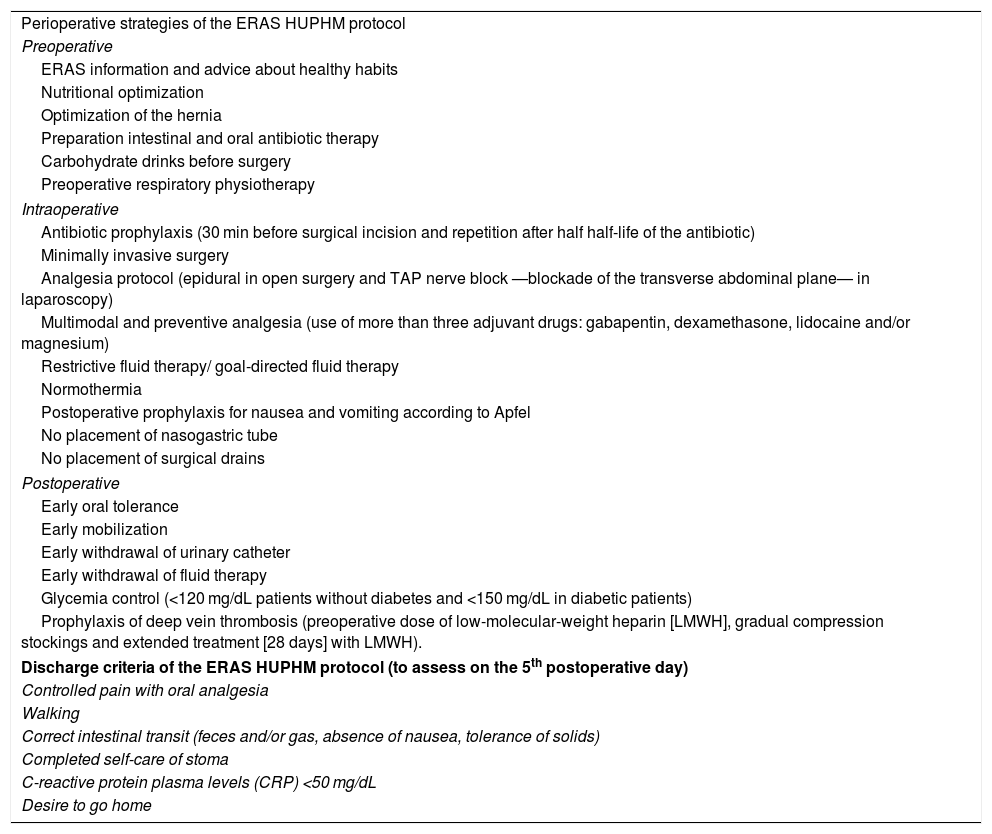

All patients followed an ERAS protocol prepared by a multidisciplinary team (anesthetists, surgeons, nurses, rehabilitators, and nutritionists), based on current guidelines and adapted to the specific characteristics of said hospital.7–9 Only two strategies included in the aforementioned protocol differ from the guidelines: all patients underwent preoperative respiratory physiotherapy instead of physical pre-habilitation and received mechanical colon preparation along with oral antibiotic therapy.

Objective discharge criteria were established by consensus and assessed on the 5th postoperative day (Table 1).

ERAS HUPHM protocol.

| Perioperative strategies of the ERAS HUPHM protocol |

| Preoperative |

| ERAS information and advice about healthy habits |

| Nutritional optimization |

| Optimization of the hernia |

| Preparation intestinal and oral antibiotic therapy |

| Carbohydrate drinks before surgery |

| Preoperative respiratory physiotherapy |

| Intraoperative |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis (30 min before surgical incision and repetition after half half-life of the antibiotic) |

| Minimally invasive surgery |

| Analgesia protocol (epidural in open surgery and TAP nerve block —blockade of the transverse abdominal plane— in laparoscopy) |

| Multimodal and preventive analgesia (use of more than three adjuvant drugs: gabapentin, dexamethasone, lidocaine and/or magnesium) |

| Restrictive fluid therapy/ goal-directed fluid therapy |

| Normothermia |

| Postoperative prophylaxis for nausea and vomiting according to Apfel |

| No placement of nasogastric tube |

| No placement of surgical drains |

| Postoperative |

| Early oral tolerance |

| Early mobilization |

| Early withdrawal of urinary catheter |

| Early withdrawal of fluid therapy |

| Glycemia control (<120 mg/dL patients without diabetes and <150 mg/dL in diabetic patients) |

| Prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis (preoperative dose of low-molecular-weight heparin [LMWH], gradual compression stockings and extended treatment [28 days] with LMWH). |

| Discharge criteria of the ERAS HUPHM protocol (to assess on the 5th postoperative day) |

| Controlled pain with oral analgesia |

| Walking |

| Correct intestinal transit (feces and/or gas, absence of nausea, tolerance of solids) |

| Completed self-care of stoma |

| C-reactive protein plasma levels (CRP) <50 mg/dL |

| Desire to go home |

After approval by the Ethics Committee, the study was conducted according to the STROBE recommendations for observational studies and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

A team was established of four anesthetists and six surgeons.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were: (1) scheduled colorectal surgery with abdominal approach; (2) signed consent form for data collection; and (3) not meeting exclusion criteria of the ERAS protocol: emergency surgeries, patients under 18 years of age or dependents, or patients with type I diabetes.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) transanal surgery; (2) lack of signed informed consent; and (3) meeting any exclusion criteria of an ERAS program.

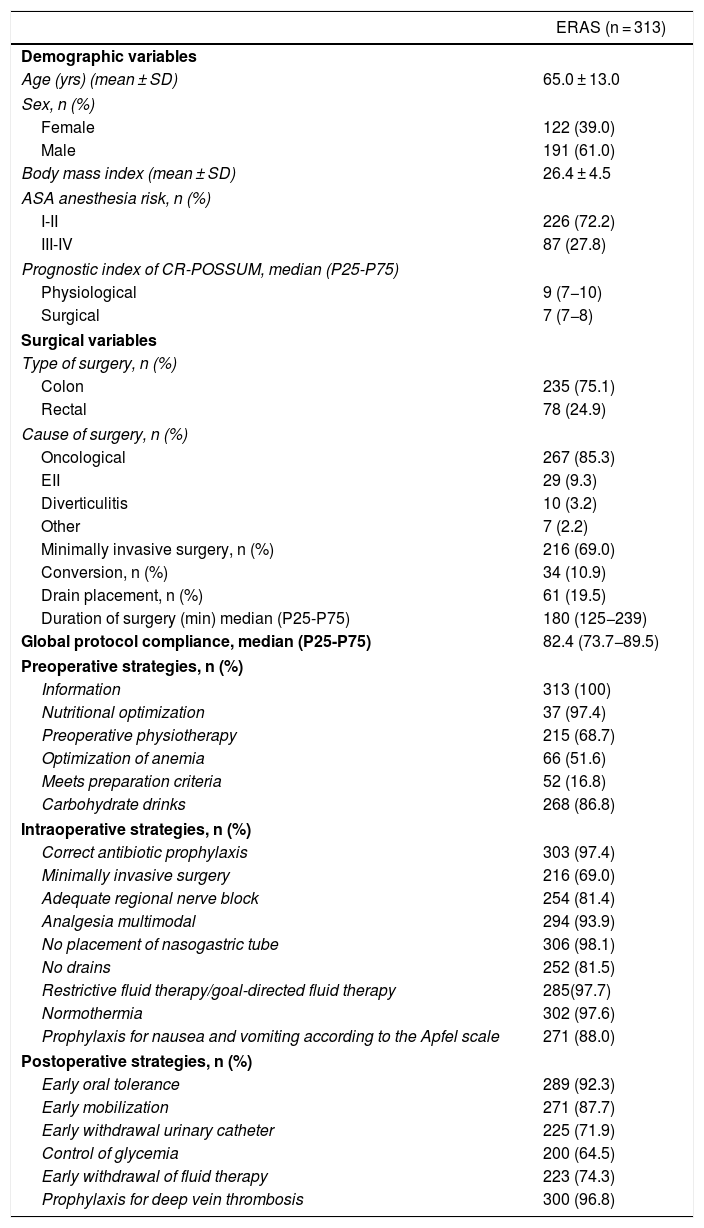

Variables studied. All the variables collected were extracted from the patients’ medical records and the computerized anesthesia chart (registered with the Piscis® and Selene® programs). Demographic characteristics were recorded, such as ASA anesthetic risk, CR-POSSUM prognostic index, and surgical variables (Table 2).

Demographic variables, surgical variables, and compliance of the ERAS HUPHM protocol strategies, according to the ERAS Society guidelines7,8.

| ERAS (n = 313) | |

|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |

| Age (yrs) (mean ± SD) | 65.0 ± 13.0 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 122 (39.0) |

| Male | 191 (61.0) |

| Body mass index (mean ± SD) | 26.4 ± 4.5 |

| ASA anesthesia risk, n (%) | |

| I-II | 226 (72.2) |

| III-IV | 87 (27.8) |

| Prognostic index of CR-POSSUM, median (P25-P75) | |

| Physiological | 9 (7−10) |

| Surgical | 7 (7−8) |

| Surgical variables | |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | |

| Colon | 235 (75.1) |

| Rectal | 78 (24.9) |

| Cause of surgery, n (%) | |

| Oncological | 267 (85.3) |

| EII | 29 (9.3) |

| Diverticulitis | 10 (3.2) |

| Other | 7 (2.2) |

| Minimally invasive surgery, n (%) | 216 (69.0) |

| Conversion, n (%) | 34 (10.9) |

| Drain placement, n (%) | 61 (19.5) |

| Duration of surgery (min) median (P25-P75) | 180 (125−239) |

| Global protocol compliance, median (P25-P75) | 82.4 (73.7−89.5) |

| Preoperative strategies, n (%) | |

| Information | 313 (100) |

| Nutritional optimization | 37 (97.4) |

| Preoperative physiotherapy | 215 (68.7) |

| Optimization of anemia | 66 (51.6) |

| Meets preparation criteria | 52 (16.8) |

| Carbohydrate drinks | 268 (86.8) |

| Intraoperative strategies, n (%) | |

| Correct antibiotic prophylaxis | 303 (97.4) |

| Minimally invasive surgery | 216 (69.0) |

| Adequate regional nerve block | 254 (81.4) |

| Analgesia multimodal | 294 (93.9) |

| No placement of nasogastric tube | 306 (98.1) |

| No drains | 252 (81.5) |

| Restrictive fluid therapy/goal-directed fluid therapy | 285(97.7) |

| Normothermia | 302 (97.6) |

| Prophylaxis for nausea and vomiting according to the Apfel scale | 271 (88.0) |

| Postoperative strategies, n (%) | |

| Early oral tolerance | 289 (92.3) |

| Early mobilization | 271 (87.7) |

| Early withdrawal urinary catheter | 225 (71.9) |

| Control of glycemia | 200 (64.5) |

| Early withdrawal of fluid therapy | 223 (74.3) |

| Prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis | 300 (96.8) |

Compliance with each of the 21 strategies that make up the ERAS HUPHM program was registered (Table 1), and compliance was considered 100% if all 21 were met. In order to compare the results with other series, we considered that colon surgery after bowel preparation did not comply with this strategy (as established by the ERAS Society guidelines).8 The strategy carried out in the first 24 postoperative hours was defined as early.

As a marker of surgical stress and functional recovery, we used plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) levels on the third postoperative day, and compliance with discharge criteria on or before the fifth day, respectively.6,10 Postoperative complications were defined and organized according to the Clavien-Dindo (CD) classification (any situation that deviates from the normal postoperative period).11

Hospital stay and readmission were recorded in the 30 days following discharge.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are expressed in absolute and relative frequencies, and numerical variables as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and P25-P75, according to compliance with the assumption of normality (Shapiro-Wilk test).

Several multivariate regression models were performed. With the independent variable ‘compliance with the protocol’, two linear regressions were done with the dependent variables ‘plasma CRP levels on the third day’ and ‘hospital stay’. Likewise, three logistic regression models were created with the dependent variables ‘had no complications’, ‘met discharge criteria’ and ‘readmission’. It was confirmed that there was no collinearity and the significance level was set at 0.05.

For the study of independent factors, all clinically relevant variables were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, and significant variables were included in the univariate analysis. Only postoperative variables were included up to day one, because it could not be determined whether they are indicators or predictors of functional recovery.

In cases with multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni correction was used.

The association between laparoscopic surgery and functional recovery was studied with the chi-squared test.

Data analysis was performed with the Stata 15.1® statistical package (StataCorp 2017, Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

ResultsDuring the study period, 322 patients were treated surgically. Nine transanal surgeries were excluded, and 313 patients were included in the study, whose characteristics are found in Table 2.

Table 2 shows the degree of compliance with each of the strategies of the protocol used. High overall compliance stood out at 82.4% (52.9; 100). The strategies with less than 70% compliance were preoperative physiotherapy, anemia optimization, meeting criteria for mechanical colon preparation, and postoperative glycemic control.

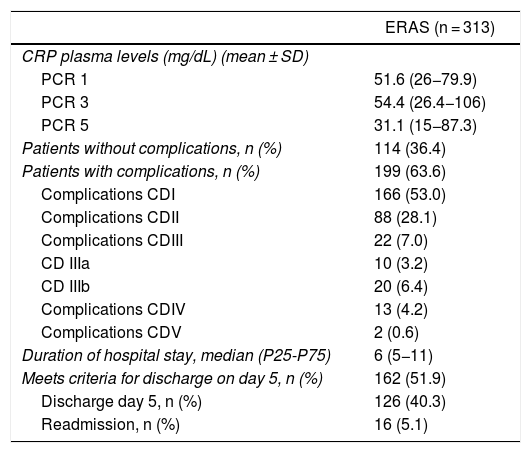

Mean postoperative CRP levels were less than 60 mg/dL on days one, three and five (Table 3).

Biochemical results, complications and postoperative evolution.

| ERAS (n = 313) | |

|---|---|

| CRP plasma levels (mg/dL) (mean ± SD) | |

| PCR 1 | 51.6 (26−79.9) |

| PCR 3 | 54.4 (26.4−106) |

| PCR 5 | 31.1 (15−87.3) |

| Patients without complications, n (%) | 114 (36.4) |

| Patients with complications, n (%) | 199 (63.6) |

| Complications CDI | 166 (53.0) |

| Complications CDII | 88 (28.1) |

| Complications CDIII | 22 (7.0) |

| CD IIIa | 10 (3.2) |

| CD IIIb | 20 (6.4) |

| Complications CDIV | 13 (4.2) |

| Complications CDV | 2 (0.6) |

| Duration of hospital stay, median (P25-P75) | 6 (5−11) |

| Meets criteria for discharge on day 5, n (%) | 162 (51.9) |

| Discharge day 5, n (%) | 126 (40.3) |

| Readmission, n (%) | 16 (5.1) |

CRP: C-reactive protein.

Postoperative complications were observed in 63.6% of the patients, the most frequent of which were type I complications (53%). The median hospital stay was six days, and 51.9% of patients reached the discharge criteria on the fifth day or earlier. However, only 40.3% were discharged on the fifth day (representing 75.9% of the patients who met discharge criteria) (Table 3).

The readmission rate was 5.1%. The most frequent causes of readmission were the need for intravenous antibiotic therapy due to surgical site infection or problems related to the ileostomy.

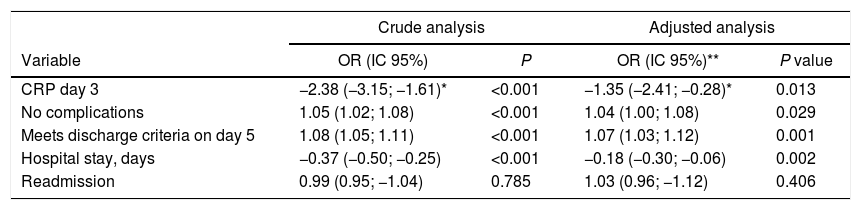

The univariate analysis demonstrated that, for each additional percentage point of compliance, the CRP on the third day decreased by 2.38 mg/dL (95%CI -3.15; -1.61, P < .001) (adjusted to the CRP from day one) and the probability of meeting discharge criteria dropped by 8% (OR 1.08, 95%CI 1.05; 1.1, P < 00.1). Also, the probability of not having complications increased by 5% (OR 1.05, 95%CI 1.02; 1.07, P < .001), and the hospital stay was reduced by 0.37 days (95% CI -0.43; -0.22, P < .001) (Table 4).

Univariate analysis of results.

| Crude analysis | Adjusted analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (IC 95%) | P | OR (IC 95%)** | P value |

| CRP day 3 | −2.38 (−3.15; −1.61)* | <0.001 | −1.35 (−2.41; −0.28)* | 0.013 |

| No complications | 1.05 (1.02; 1.08) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.00; 1.08) | 0.029 |

| Meets discharge criteria on day 5 | 1.08 (1.05; 1.11) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.03; 1.12) | 0.001 |

| Hospital stay, days | −0.37 (−0.50; −0.25) | <0.001 | −0.18 (−0.30; −0.06) | 0.002 |

| Readmission | 0.99 (0.95; −1.04) | 0.785 | 1.03 (0.96; −1.12) | 0.406 |

CRP: C-reactive protein.

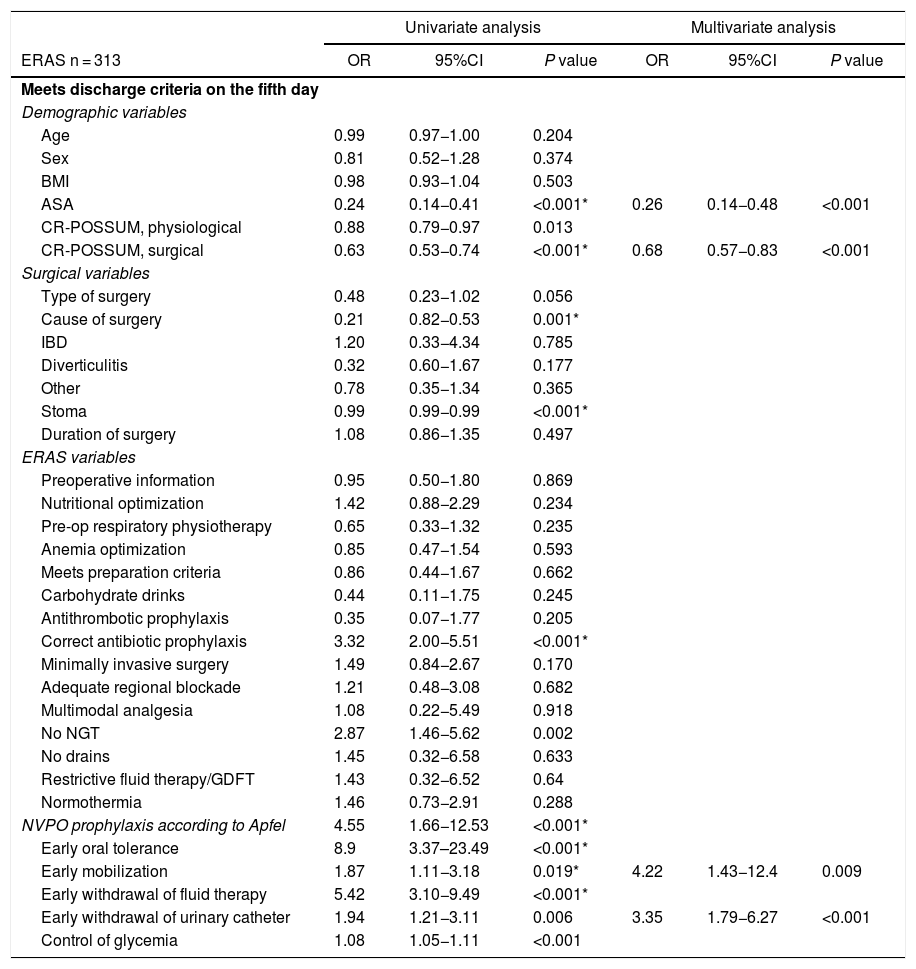

In the maximum model, ASA I-II were associated with an almost four times greater chance of meeting the discharge criteria. For each point less on the surgical CR-POSSUM scale, there was a 32% greater chance of meeting criteria; early mobilization and removal of the urinary catheter were associated with a 4.22- and 3.35-times greater probability of meeting discharge criteria, respectively (Table 5).

Multivariate analysis of independent factors associated with meeting discharge criteria on the fifth day or before.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERAS n = 313 | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Meets discharge criteria on the fifth day | ||||||

| Demographic variables | ||||||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.97−1.00 | 0.204 | |||

| Sex | 0.81 | 0.52−1.28 | 0.374 | |||

| BMI | 0.98 | 0.93−1.04 | 0.503 | |||

| ASA | 0.24 | 0.14−0.41 | <0.001* | 0.26 | 0.14−0.48 | <0.001 |

| CR-POSSUM, physiological | 0.88 | 0.79−0.97 | 0.013 | |||

| CR-POSSUM, surgical | 0.63 | 0.53−0.74 | <0.001* | 0.68 | 0.57−0.83 | <0.001 |

| Surgical variables | ||||||

| Type of surgery | 0.48 | 0.23−1.02 | 0.056 | |||

| Cause of surgery | 0.21 | 0.82−0.53 | 0.001* | |||

| IBD | 1.20 | 0.33−4.34 | 0.785 | |||

| Diverticulitis | 0.32 | 0.60−1.67 | 0.177 | |||

| Other | 0.78 | 0.35−1.34 | 0.365 | |||

| Stoma | 0.99 | 0.99−0.99 | <0.001* | |||

| Duration of surgery | 1.08 | 0.86−1.35 | 0.497 | |||

| ERAS variables | ||||||

| Preoperative information | 0.95 | 0.50−1.80 | 0.869 | |||

| Nutritional optimization | 1.42 | 0.88−2.29 | 0.234 | |||

| Pre-op respiratory physiotherapy | 0.65 | 0.33−1.32 | 0.235 | |||

| Anemia optimization | 0.85 | 0.47−1.54 | 0.593 | |||

| Meets preparation criteria | 0.86 | 0.44−1.67 | 0.662 | |||

| Carbohydrate drinks | 0.44 | 0.11−1.75 | 0.245 | |||

| Antithrombotic prophylaxis | 0.35 | 0.07−1.77 | 0.205 | |||

| Correct antibiotic prophylaxis | 3.32 | 2.00−5.51 | <0.001* | |||

| Minimally invasive surgery | 1.49 | 0.84−2.67 | 0.170 | |||

| Adequate regional blockade | 1.21 | 0.48−3.08 | 0.682 | |||

| Multimodal analgesia | 1.08 | 0.22−5.49 | 0.918 | |||

| No NGT | 2.87 | 1.46−5.62 | 0.002 | |||

| No drains | 1.45 | 0.32−6.58 | 0.633 | |||

| Restrictive fluid therapy/GDFT | 1.43 | 0.32−6.52 | 0.64 | |||

| Normothermia | 1.46 | 0.73−2.91 | 0.288 | |||

| NVPO prophylaxis according to Apfel | 4.55 | 1.66−12.53 | <0.001* | |||

| Early oral tolerance | 8.9 | 3.37–23.49 | <0.001* | |||

| Early mobilization | 1.87 | 1.11−3.18 | 0.019* | 4.22 | 1.43−12.4 | 0.009 |

| Early withdrawal of fluid therapy | 5.42 | 3.10−9.49 | <0.001* | |||

| Early withdrawal of urinary catheter | 1.94 | 1.21−3.11 | 0.006 | 3.35 | 1.79−6.27 | <0.001 |

| Control of glycemia | 1.08 | 1.05−1.11 | <0.001 | |||

BMI, body mass index; IBD, intestinal bowel disease; NGT, nasogastric tube; GDFT, goal-directed fluid therapy.

Functional recovery was achieved in 60.9% of the patients who underwent laparoscopy and 32.0% of those who underwent open surgery (P < .001).

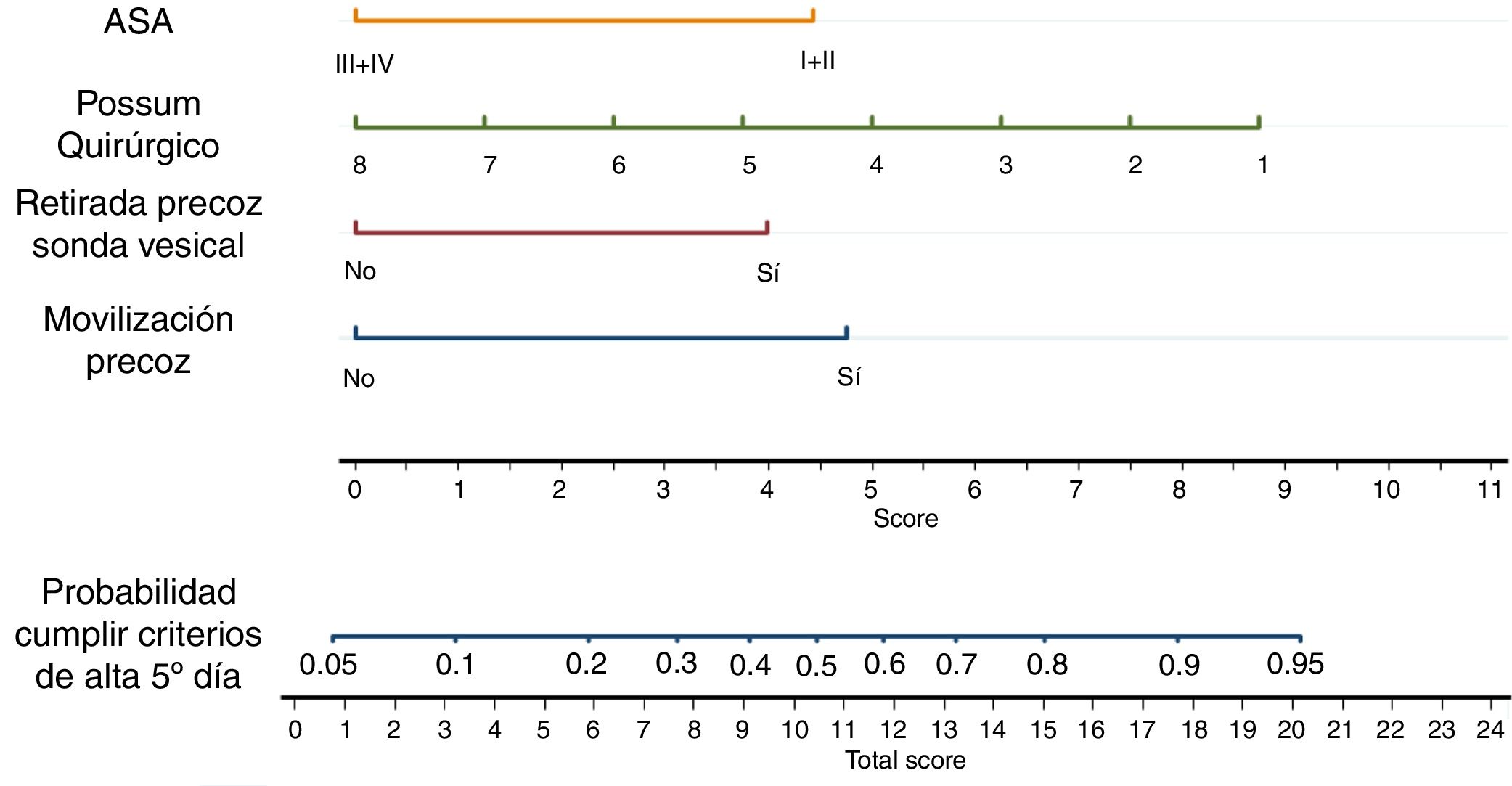

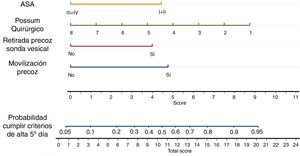

The nomogram in Fig. 1 was used to calculate the probability of a patient to meet discharge criteria on or before the fifth day.

Nomogram of independent factors in order to meet discharge criteria on the fifth day.

Graphic representation of the maximum model, which allows us to obtain the probability of meeting discharge criteria on the 5th day, adding the points corresponding to the patient characteristics. For example, one patient with a POSSOM Q score of 4 (+5 points), and an ASA of III (+0 points), with withdrawal of the urinary catheter on the first day (+4 points) and early mobilization (+4.5 points) for a total of 13.5 points. This patient has a probability of meeting discharge criteria on the 5th day of 70%.

This study shows that greater compliance with an ERAS protocol in colorectal surgery is not only associated with less surgical stress and faster functional recovery, but also with a lower rate of complications and hospital stay. Overall adherence was high, and ASA I/II, early mobilization and urinary catheter removal were identified as independent factors for functional recovery.

Although there are more specific markers of surgical stress, we used CRP levels due to their high accessibility and their standard use in the postoperative period of this type of surgery.10,12–14 We chose the fulfillment of discharge criteria as a measure of functional recovery, since hospital stay can be influenced by social issues or the doctor’s preferences. This can be observed in our cohort, where only 75% of the patients who met the criteria for discharge were actually discharged. The evaluation of the criteria for discharge on the 5th postoperative day may seem late, considering that the guidelines establish assessing discharge from the 3rd day in colorectal surgery. We decided to establish it like this in order to strengthen the team’s confidence in the ERAS program, since it was a team that was not experienced in working with these protocols.7–9

The complication rate may seem high compared to other series that use more restrictive definitions, such as the ACS NSQIP or the proposal by Lang. Some studies, despite using the Clavien-Dindo classification, do not even consider nausea and vomiting or phlebitis complications, despite being recognized factors for delaying functional recovery.1,15–18

In the descriptive analysis of the cohort, the high degree of global compliance was notable, ranking above all the series cited in the article as well as the national average (10% more than mean global compliance).19 It is especially difficult to achieve these degrees of compliance with the protocol in recently started programs (such as ours), where there is usually an initial adaptation period of low compliance.3,20 The high compliance with intra- and postoperative strategies reflects a well-designed clinical circuit and a high level of team commitment, for which the creation of an established team was essential. The analysis also highlighted the low compliance with the criteria for mechanical preparation of the colon. While developing the ERAS HUPHM protocol, we established routine bowel preparation with oral antibiotic therapy based on articles that had been recently published at that time, where this strategy was associated with a reduction of surgical site infection and suture dehiscence rates.21–23

The hospital stay of the study is shorter than the national average (one day less than the average stay for hospitals that practice ERAS), and the rate of readmission is 50% lower than in series with similar hospital stays.3,19 Furthermore, given that no readmitted patient has needed to be reoperated or admitted to the ICU, the discharge criteria seem safe.

As in other studies, ASA I/II, early mobilization and removal of the urinary catheter are identified as risk factors for achieving functional recovery.4,20 Pelvic surgery (whose complexity determines the surgical CR-POSSUM) had also been identified as a risk factor for prolonged stay.3

Laparoscopy is significantly associated with functional recovery. However, it is not identified as an independent factor in the multivariate analysis, since it is explained by the elements that remain after the analysis. In fact, laparoscopic surgery itself favors compliance with postoperative strategies that remain independent factors, as has already been observed in other studies.20

Despite being a prospective cohort, this study has the intrinsic limitations of a single-center observational study, and the sample size may seem insufficient to carry out regression models due to the high number of predictors studied. Other limitations are that long-term outcomes (such as survival), satisfaction ratings, or subjective patient outcomes have not been included. Strengths of the study include the use of clear and concise definitions, that the protocol was designed according to current guidelines, the multivariate models are adjusted to the main confounding factors (comorbidities and surgical characteristics) and populations with a higher risk of associated comorbidity (such as pelvic surgery or inflammatory bowel disease) have not been eliminated from the series, which gives it external validity.

In conclusion, increasing compliance with the ERAS protocol in colorectal surgery reduces surgical stress and increases functional recovery, in addition to reducing complications and hospital stay.

FundingThis study has received no funding from public, commercial, or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank all the doctors, nurses and nursing assistants involved in any of the steps of the ERAS program, with special thanks to Ana Royuela for her statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: Barbero M, García J, Alonso I, Alonso L, San Antonio-San Román B, Molnar V, et al. Impacto del grado de cumplimiento de un protocolo ERAS en la recuperación funcional después de cirugía colorrectal. Cir Esp. 2021;99:108–114.