Both obesity and rapid weight loss after bariatric surgery are known risk factors for the formation of biliary lithiasis,1 and there is a higher incidence after bypass versus restrictive techniques.2 Brockmeyer et al.3 have reported 8% of biliary symptoms after gastric bypass and 1.6% after vertical sleeve gastrectomy, while Sucandy et al.2 have reported 22% after duodenal switch. 10%–15% of patients with gallstones can develop choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, pancreatitis or gallstone ileus. When this happens after bariatric surgery, the diagnostic-therapeutic management can be especially complex in diversion techniques due to the difficult access of the papilla and the common bile duct.4 We present the case of a patient who had undergone duodenal switch for morbid obesity, who, 11 years after surgery, presented cholelithiasis and subsequent cholangitis. Both diagnosis and resolution were challenging for the team, which required altering the bariatric technique.

The patient is a 59-year-old woman with a history of appendectomy and stenosis of the lumbar spinal canal. In 2001, she was treated for morbid obesity (45kg/m2) at another hospital and underwent open biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Vertical gastrectomy was performed with pyloric preservation and duodeno-ileal bypass, leaving 50cm of biliopancreatic loop and 75cm of common loop. Two years later, and after good weight loss, the patient underwent incisional hernia repair and abdominoplasty. Eleven years after diversion surgery (2012), she presented with biliary pancreatitis, and open cholecystectomy was performed.

The patient first came to our hospital in January 2013 with recurrent episodes of high fever, epigastric abdominal pain and chills, which remitted with antibiotics. Physical examination was normal, BMI was 23kg/m2 and blood work showed mild cholestasis. Ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) were performed, which found residual choledocholithiasis of the distal bile duct. We decided to conduct bile duct exploration by laparotomy and, after a failed attempt of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography through the biliopancreatic loop, we performed choledochotomy, bile duct clearance and choledochoduodenostomy.

In the postoperative period, cholangitis crises recurred, with positive blood cultures for Escherichia coli. MRCP showed millimetric repletion defects in the pre-pancreatic bile duct, compatible with microlithiasis or detritus. With the diagnosis of sump syndrome, transparietal-hepatic dilatations were carried out through the sphincter of Oddi. However, due to the lack of response to the interventional treatment and the severity of the condition, the patient was reoperated to perform transduodenal sphincteroplasty and Kehr drain tube placement (November 2013). The cholangiographies through the Kehr tube showed good filling of the bile duct and drainage to the duodenum with no difficulties.

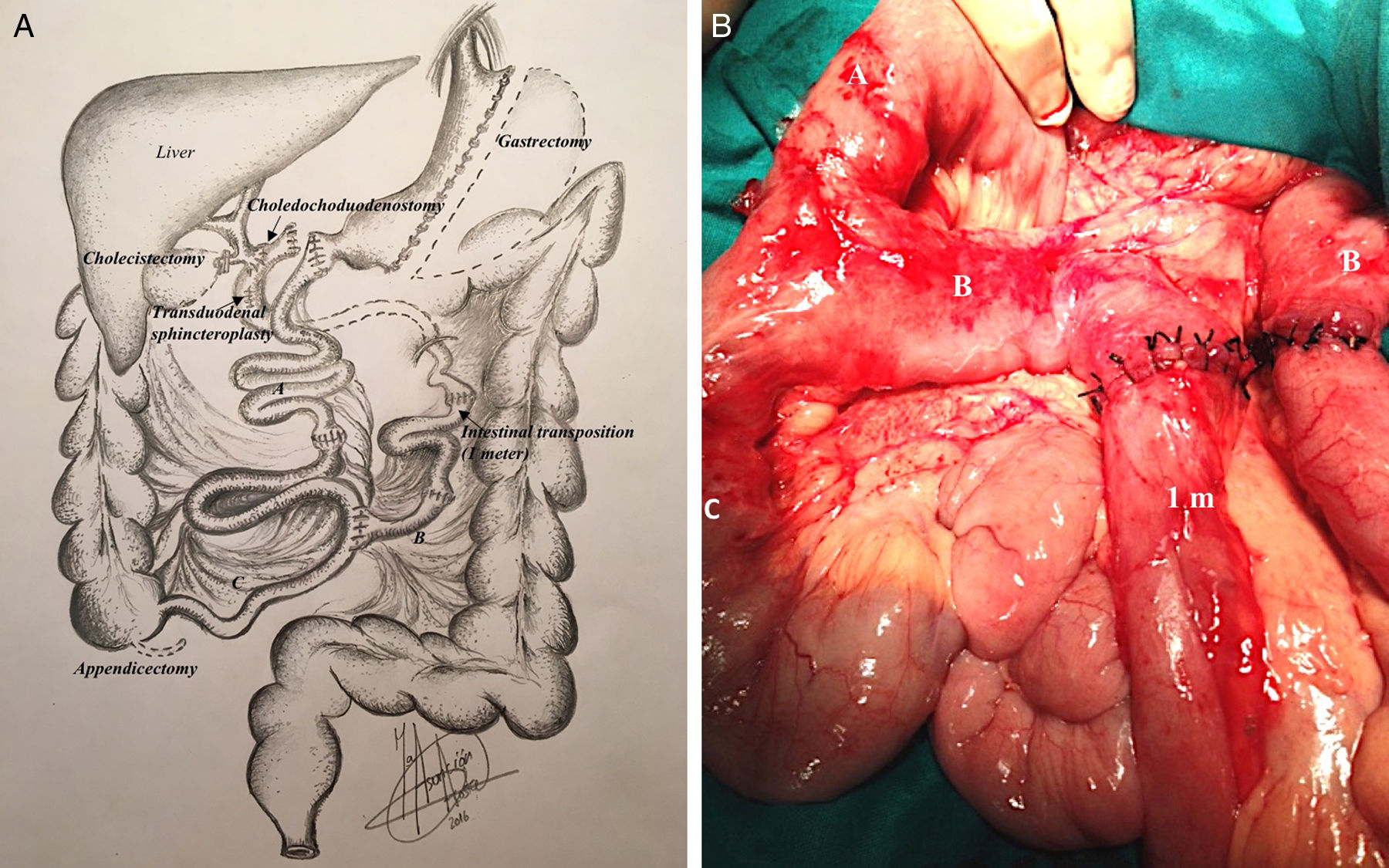

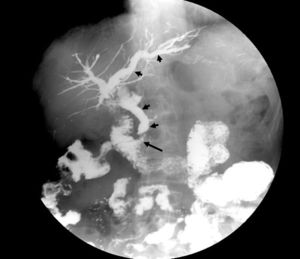

After a brief improvement, the patient again presented episodes of high fever (39–40°C), shivering and pain, requiring several hospital readmissions and continuous administration of antibiotic therapy. Abdominal CT was performed, which ruled out intra-abdominal collections, free fluid or alterations in the biliary tract. Hepatobiliary scintigraphy (185MBq 99mTc-mebrofenin) found no obstruction or delay of biliary emptying, and entero-resonance showed no lesions in the intestinal loops. Finally, a barium transit study showed contrast reflux in the biliopancreatic loop of the duodenal switch, filling the entire biliary tree (Figure 1). With the diagnosis of reflux cholangitis from the biliopancreatic loop of the duodenal switch to the biliary tract, and in order to treat this perpetuating component of cholangitis, revision surgery was conducted (November 2014) to modify the loop lengths, removing a 1m section from the intestinal loop and interposing it in the biliopancreatic loop (Figure 2A and B). The patient progressed satisfactorily, except for intercurrent diarrhea caused by Clostridium difficile, which responded to antibiotic therapy. The patient was discharged after 22 days. Three years later, the patient has not presented cholangitis again, nor does she show malabsorption after the shortening of the intestinal loop. The only observation is a small incisional hernia from the laparotomy.

Surgical technique: (A) diagram of the surgical technique for transpositioning one meter of intestinal loop to the biliopancreatic loop of the duodenal switch; (B) intraoperative image showing the intestinal loop (A), biliopancreatic loop (B), common loop (C) and the 1m intestinal segment inserted in the middle of the biliopancreatic loop.

The key study for the definitive resolution of the condition was a barium transit test, which showed reflux toward the biliary tree from the biliopancreatic loop. This guided us in the choice of the appropriate therapy, involving the lengthening of the loop at the expense of the intestinal loop. Larrad-Jiménez et al.5 described a modification in the length of the loops (short biliopancreatic and long intestinal) on the Scopinaro et al. biliopancreatic diversion.6 This modification has been applied to the duodenal switch by some authors,7 as in our case. Although the length of the biliopancreatic loop in the Larrad-Jiménez et al. technique was 50cm, this procedure was not accompanied by a higher rate of biliary complications while the sphincter mechanism remains intact.5 We think that the integrity of the papilla plays a fundamental role and that papillotomy could favor reflux.

Choledochoduodenostomy, which is widely advocated8–10 for the management of choledocholithiasis, presents the risk of favoring alimentary reflux of the biliopancreatic loop toward the bile duct in patients with bariatric diversion surgery. This worsens if we add sphincterotomy for “sump syndrome”. Alqahtani et al.4 treated a case of cholangitis after gastric bypass using choledochoduodenostomy to avoid interference with the Roux-en-Y and in the end had to convert to a hepaticojejunostomy due to sump syndrome.

We propose evaluating the lengthening of the biliopancreatic loop as an effective alternative to treat cholangitis after duodenal switch, whose perpetuating element is biliary reflux due to loss of the integrity of the sphincter mechanism of the papilla.

Please cite this article as: Acosta Mérida MA, Marchena Gómez J, Ferrer Valls JV, Larrad Jiménez Á, Casimiro Pérez JA. Prolongación del asa biliopancreática para el control del reflujo enterobiliar tras coledocoduodenostomía en un cruce duodenal. Cir Esp. 2018;96:379–381.