Since the number of applicants to residencies in general surgery in Argentina seems to be decreasing, we designed this work with the objective of studying the factors considered undesirable by students when choosing surgery as a specialty.

Material and methodsBetween March and April 2012, one-hundred students were surveyed with a structured questionnaire with true/false binary answers in an observational case–control design. The survey contained 26 statements that made reference to characteristics of surgery as a specialty, or about the personality and lifestyle of surgeons, as they could be perceived by students. As a control group the same survey was applied to 20 surgeons who were in contact with the students and that could represent a role model for them during their rotation in surgery.

ResultsComparison between students and surgeons showed no difference in most answers, except in “surgery has poor reimbursement” (OR: 8.9; P=.0001), “there is not enough job demand” (OR: 8.1; P=.015), “surgery restrains intellectual development” (OR: 17.5; P=.014), “surgeons have too many non-scheduled activities” (OR: 9.36; P=.024), “they have a limited patient–physician relationship” (OR: 3.61; P=.009), “they have little time for family” (OR: 4.27; P=.036) and “they are exposed to infectious diseases” (OR: 5.90; P=.007).

ConclusionsWomen would be as interested as men in working as surgeons; a remarkable fact when considering that the surgical specialties have been predominantly filled by men. The fact that surgeons mostly coincide with the views of students means that role models should be reviewed to promote vocations.

Dado que el número de aspirantes a las residencias en cirugía en Argentina parece estar disminuyendo, se realizó este trabajo con el objetivo de estudiar cuáles eran los factores que los estudiantes consideraban indeseables a la hora de elegir la cirugía como especialidad.

Material y métodosEntre marzo y abril de 2012 se encuestó a 100 alumnos de la materia cirugía mediante un diseño observacional de caso-control. La encuesta contenía 26 afirmaciones referidas a algunas características de la cirugía como especialidad, o a la personalidad y estilo de vida de los cirujanos, según podían ser percibidas por los estudiantes. La misma encuesta se aplicó a 20 cirujanos que estaban en contacto con los alumnos y que podían representar un modelo para ellos durante su rotación en la materia.

ResultadosAl comparar alumnos y cirujanos no hubo diferencias en la mayoría de las respuestas, excepto en «la cirugía no está bien pagada» (OR: 8,9; p=0,0001), «no tiene mucha demanda laboral» (OR: 8,1; p=0,015), «limita el crecimiento intelectual» (OR: 17,5; p=0,014), «los cirujanos tienen muchas actividades no programadas» (OR: 9,36; p=0,024), «tienen una relación médico-paciente limitada» (OR: 3,61; p=0,009), «tienen poco tiempo para la familia» (OR: 4,27; p=0,036) y «tienen riesgo alto de exposición a infecciones» (OR: 5,90; p=0,007).

ConclusionesLas mujeres estarían tan interesadas como los varones en ejercer la cirugía; hecho destacable si se considera que las especialidades quirúrgicas han sido predominantemente masculinas. El hecho de que los cirujanos coincidieran mayormente con las opiniones de los estudiantes exigiría la revisión del rol de aquellos como modelos para promover las vocaciones.

The choice of a specialty is a decision required of recent graduates who opt for a career in medicine. In addition to the subjective value of vocation, there are other factors that seem to influence students’ choices, including job opportunities, the prestige of the specialty among colleagues and patients, duration of the training period, anticipated salary, and expected lifestyle and quality of life.1–4

In Argentina, the number of aspiring graduates for admission to general surgery residencies does not seem to have increased proportionally with the number of graduates. At the Universidad of Buenos Aires, the number of applicants to surgical programs only grew 13% from 2009 to 2012; meanwhile, the applicants to pediatrics, for example, rose 32%.5 This trend was also a cause for concern in the U.S., where an increase was reported in the number of unfilled positions in the National Resident Matching Program.6 Almost one decade earlier, the same problem of a dwindling interest in surgical specialties was identified in Spain7; consequently, plans were proposed to reduce the workload of residents in the emergency department8 and to implement new teaching technologies in the undergraduate program in order to make surgery more attractive.9 Reports from postgraduates who choose surgery as a specialty suggest that these decisions were already made at the beginning of their university studies. This study observed that, when students in their fifth year were surveyed, 15% still had not decided which specialty to pursue. It was expected that, by the end of their degree, this percentage of “undecided students” would be proportionally distributed among the different specialties. But, when the students were again surveyed 2 months before finishing their studies, this percentage of undecided students was ultimately divided amongst the other specialties, to the detriment of surgery.10,11 This would support the concept that the choice for surgery would be made earlier on in the decision-making process of the candidates and, consequently, undergraduate contact with the subject matter might not be determinant in opting for this specialty. Thus, the exposure of students to more attractive rotations during their coursework would not modify the perception that they already had of the material, particularly with regards to lifestyle.1

Given the challenge for finding ways to promote interest in surgery, the following study was designed in order to study which factors were considered undesirable by students when choosing surgery as a specialty.

Materials and MethodsBetween March and April 2012, 100 surgery students at the Hospital de Clínicas of the University of Buenos Aires (Argentina) were surveyed. The study design was an observational case–control analysis that intended to analyze the relationship between the condition of choosing or not choosing surgery as a specialty; different factors were included in the survey questions. The questionnaire, which had been adapted from Gelfand et al.,1 was a structured type with dichotomous responses and was made up of a group of statements or declarations that the students responded to with the options of “true” or “false”. Out of the 26 statements, the first 16 referred to characteristics of surgery as a specialty, as perceived by students. The 10 remaining statements referred to personality and lifestyle characteristics of surgeons, also according to the perception of survey participants. In addition, information was obtained for the age, sex and intention of choosing surgery as a specialty in the future. The questionnaire was self-administered and the responses were anonymous. For the analysis of the results, the “true” responses were considered positive and “false” were negative. We obtained the percentage of positive results for all of the participants, accompanied by the 95% confidence interval. In addition, we compared the percentages of separate positive responses according to whether the students would choose surgery as a specialty or not. Last of all, as we foresaw that the teaching surgeons could have a decisive influence on student responses, we applied the same survey in a group of 20 surgeons who were in contact with the students and could represent a role model for them during their surgery rotations. In accordance with the design, comparisons between groups were performed with the 95% confidence interval of the odds ratio (OR) and the Chi-squared or Fisher's tests. The normal distribution of age was analyzed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the comparison of ages between males and females was done with the Mann–Whitney test. The level of significance for P was established at .05. The calculation of the student sample size to estimate proportions was based on a 95% confidence interval, an estimated proportion of 0.5 and a maximum admissible error of 0.1 (n=96). The sample of 100 students was recruited in a non-probabilistic manner from among those who were studying the course matter in the defined time period, while the sample of teaching surgeons was chosen randomly from among the total group of surgery professors.

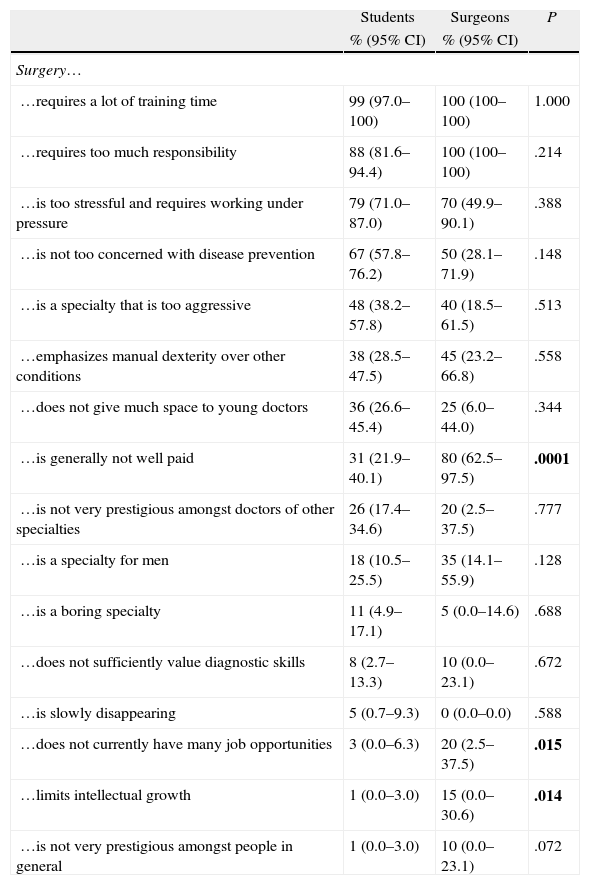

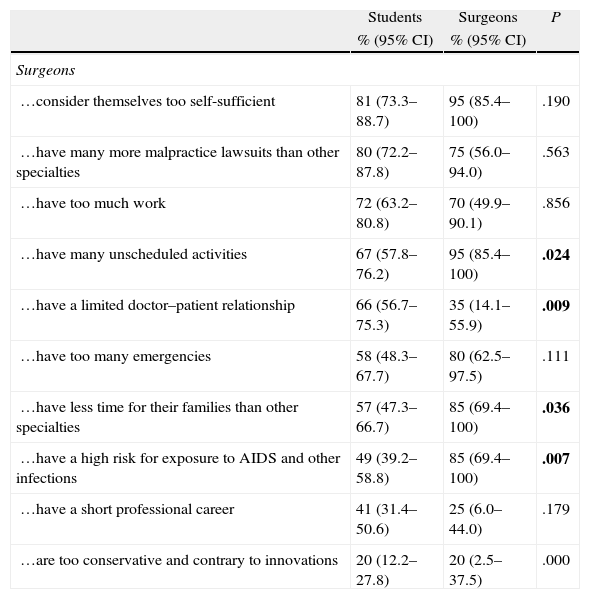

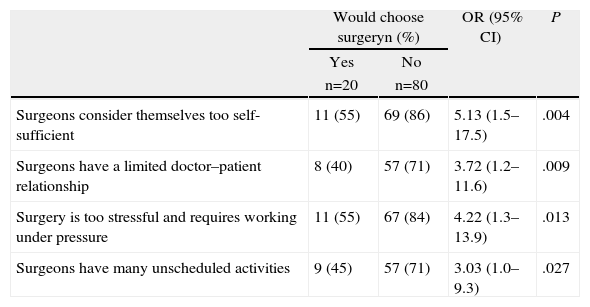

ResultsComplete responses were collected from all the students surveyed. 74% were women with a mean age of 25.9±3 and the remainder were men with a mean age of 27.5±6 (P=.204). This sample was representative of the proportion of men and women who were enrolled at the University of Buenos Aires at that time. Table 1 shows the percentages of positive responses from the total population when asking about the characteristics perceived by the students and the surgeons regarding surgery as a specialty. When we compared the opinions of students and surgeons, there were no differences in the percentage of true responses in most of the statements, except for “Surgery is not well paid,” (OR: 8.9 [95%CI: 2.50–34.6]; P=.0001), “There are not many job opportunities,” (OR: 8.08 [95%CI: 1.35–51.5]; P=.015) and “Limits intellectual growth,” (OR: 17.5 [95%CI: 1.47–464.2]; P=.014); meanwhile, “It is a male specialty,” (OR: 2.45 [95%CI: 0.76–7.86]; P=.128) and “It is not prestigious enough,” (OR: 11.0 [95%CI: 0.72–325.1] P=.072) were borderline significant. As for the comparison between sexes among the students, 6 (23%) males and 12 (16%) females were of the opinion that surgery was a male specialty (P=.553). Table 2 shows the percentages of positive responses in the total population when asked about the characteristics perceived by the students and the surgeons regarding surgeons themselves as specialists. The comparison of opinions between students and surgeons showed differences in “Surgeons have many unscheduled activities” (OR: 9.36 [1.23–195.6]; P=.024), “They have a limited doctor–patient relationship” (OR: 3.61 [1.20–11.2]; P=.0099, “They have little family time” (OR: 4.27 [1.08–19.7]; P=.036) and “They have a high risk of exposure to infections” (OR: 5.90 [1.49–27.1]; P=.007). When comparing between the sexes, 14 (54%) males and 42 (57%) women agreed that surgeons, more than other specialists, would have little time to spend with their families (P=.797). 20% of all the survey participants reported that they would choose surgery as their specialty. Out of these, 6 (30%) were males and the rest were females (n=14), which did not differ from the expected male/female ratio (26% versus 74%; P=.641). Table 3 summarizes the statistically significant results by comparing the positive responses according to whether the students would choose surgery as a specialty or not.

Percentage of Positive Responses When Asking About the Characteristics Perceived by Students (n=100) and Surgeons (n=20) Regarding Surgery as a Specialty.

| Students | Surgeons | P | |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||

| Surgery… | |||

| …requires a lot of training time | 99 (97.0–100) | 100 (100–100) | 1.000 |

| …requires too much responsibility | 88 (81.6–94.4) | 100 (100–100) | .214 |

| …is too stressful and requires working under pressure | 79 (71.0–87.0) | 70 (49.9–90.1) | .388 |

| …is not too concerned with disease prevention | 67 (57.8–76.2) | 50 (28.1–71.9) | .148 |

| …is a specialty that is too aggressive | 48 (38.2–57.8) | 40 (18.5–61.5) | .513 |

| …emphasizes manual dexterity over other conditions | 38 (28.5–47.5) | 45 (23.2–66.8) | .558 |

| …does not give much space to young doctors | 36 (26.6–45.4) | 25 (6.0–44.0) | .344 |

| …is generally not well paid | 31 (21.9–40.1) | 80 (62.5–97.5) | .0001 |

| …is not very prestigious amongst doctors of other specialties | 26 (17.4–34.6) | 20 (2.5–37.5) | .777 |

| …is a specialty for men | 18 (10.5–25.5) | 35 (14.1–55.9) | .128 |

| …is a boring specialty | 11 (4.9–17.1) | 5 (0.0–14.6) | .688 |

| …does not sufficiently value diagnostic skills | 8 (2.7–13.3) | 10 (0.0–23.1) | .672 |

| …is slowly disappearing | 5 (0.7–9.3) | 0 (0.0–0.0) | .588 |

| …does not currently have many job opportunities | 3 (0.0–6.3) | 20 (2.5–37.5) | .015 |

| …limits intellectual growth | 1 (0.0–3.0) | 15 (0.0–30.6) | .014 |

| …is not very prestigious amongst people in general | 1 (0.0–3.0) | 10 (0.0–23.1) | .072 |

Significant P values are in bold (P<05).

Percentage of Positive Responses When Asking About the Characteristics Perceived by Students (n=100) and Surgeons (n=20) Regarding Surgeons as Specialists.

| Students | Surgeons | P | |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||

| Surgeons | |||

| …consider themselves too self-sufficient | 81 (73.3–88.7) | 95 (85.4–100) | .190 |

| …have many more malpractice lawsuits than other specialties | 80 (72.2–87.8) | 75 (56.0–94.0) | .563 |

| …have too much work | 72 (63.2–80.8) | 70 (49.9–90.1) | .856 |

| …have many unscheduled activities | 67 (57.8–76.2) | 95 (85.4–100) | .024 |

| …have a limited doctor–patient relationship | 66 (56.7–75.3) | 35 (14.1–55.9) | .009 |

| …have too many emergencies | 58 (48.3–67.7) | 80 (62.5–97.5) | .111 |

| …have less time for their families than other specialties | 57 (47.3–66.7) | 85 (69.4–100) | .036 |

| …have a high risk for exposure to AIDS and other infections | 49 (39.2–58.8) | 85 (69.4–100) | .007 |

| …have a short professional career | 41 (31.4–50.6) | 25 (6.0–44.0) | .179 |

| …are too conservative and contrary to innovations | 20 (12.2–27.8) | 20 (2.5–37.5) | .000 |

Comparison of the Positive Responses According to Whether Students Would Choose Surgery as a Specialty or Not (Includes Only Those Results That Reached a P of .05).

| Would choose surgeryn (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Yes | No | |||

| n=20 | n=80 | |||

| Surgeons consider themselves too self-sufficient | 11 (55) | 69 (86) | 5.13 (1.5–17.5) | .004 |

| Surgeons have a limited doctor–patient relationship | 8 (40) | 57 (71) | 3.72 (1.2–11.6) | .009 |

| Surgery is too stressful and requires working under pressure | 11 (55) | 67 (84) | 4.22 (1.3–13.9) | .013 |

| Surgeons have many unscheduled activities | 9 (45) | 57 (71) | 3.03 (1.0–9.3) | .027 |

Different factors could influence the choice of a medical specialty, such as job opportunities, prestige, salary and lifestyle. When asked whether surgery had little or decreasing job opportunities, most students responded negatively; therefore, this would not be a condition for not choosing surgery as a specialty. The same happened when dealing with the specialty's prestige, either among people at large or to a lesser degree among colleagues from other specialties (one quarter of those surveyed considered that surgery was not very prestigious amongst doctors of other specialties). As for remuneration, only one-third of the students reported that surgery was not a well-paid specialty. In contrast, the variables related with lifestyle could be the most significant factors for choosing surgery. In general, the students responded that surgery required a lot of training time, required too much responsibility, was stressful and work was done under pressure, which were answers that coincided with those of the surgeons.

The students agreed that surgeons are usually considered too self-sufficient, are exposed to more malpractice lawsuits and have too many unscheduled activities, which are opinions that also coincided with those of the surgeons surveyed. Most of these factors would be related with a poorer lifestyle that would limit the choice of the specialty. In particular, some responses of the surgeons that differed from the opinions of the students, such as “Surgery is not well paid,” “Surgery does not currently have many job opportunities,” and “Surgery limits intellectual growth” seemed to be more related with current career conflicts of surgeons.

When we compared the opinion of those who would choose surgery versus those who would not, 4 significant variables were identified. Two of them were once again associated with quality of life and are those that report that “Surgery is too stressful and requires working under pressure” and that “Surgeons have many unscheduled activities”. The other 2 factors indicate the undesirable characteristics of surgeons: their self-sufficient profile and the perception that surgeons have limited doctor–patient relationships. If these findings are considered, coursework in surgery would offer us the opportunity to change the students’ perception. However, their opinions for those items were no different from the opinions of the teaching surgeons, except for the statement that the doctor–patient relationship is limited.

Traditionally, surgery has been a specialty for men,2,9 and even one-third of the surgeons surveyed agreed with this statement. In spite of this, our study has revealed that women could be good candidates since, when compared with the men, the women did not consider that surgery was particularly a specialty for men, and a similar proportion declared that they would choose surgery as a specialty. In addition, the female participants gave the same importance as males to the statement that surgeons have little time to spend with their families.

In a recent survey, medical students were asked about their perceptions regarding the prestige, job opportunities, remuneration, lifestyle and training time required in 20 different specialties.10 Surgery was chosen as the most prestigious specialty by 87%, although a similar percentage considered that it also required more training time. In this list, surgery was ranked second among the specialties that were best paid, but also among those that would have a less controllable lifestyle, defined as the condition of having more emergencies, night-time calls and duties, or unscheduled activities. In spite of this good reputation, surgery was chosen as a specialty by only 7% of a cohort of more than 200 students at the same university.10,11 A local reality that could explain this situation could be the high proportion of female students, who characteristically are less involved in the surgical specialties.

Although stress was one of the factors associated with not choosing surgery, the perception of stress could have a relevant cultural component as stress was not perceived as an influential factor in a sample of Pakistani graduates who decided to choose a surgical specialty.12

Other studies suggest that the best way to attract and maintain the interest of students for surgery would be to expose them to attractive models of professional practice, patient care activities and research.13,14 Likewise, the application of computer technologies15 and the quality control of residency programs would help make the specialty more attractive.16

In agreement with our findings, Gelfand et al.1 analyzed the loss of interest in surgery of American students. They concluded that the students preferred to choose specialties with a “friendlier” lifestyle, with less stress and work commitments and more free time. In a recent survey, Kaderli et al.17 indicated that the proportion of graduates who choose to study surgery in Switzerland is falling, as in the majority of European countries, and that the only significant predictor for not choosing the specialty would be the prolonged training time required by surgery. In another survey done in students in the UK, Corrigan et al.18 found that the factors related with lifestyle were determinant when deciding on surgery. Other authors also observed that lifestyle seemed to be a priority for students, which led to the reduction in the number of candidates for general surgery residency programs in the U.S.19,20 For this reason, a series of evaluations and reforms of general surgery training programs have recently been initiated in order to ensure the workforce for the future.21,22 In any event, this situation is not the cause of the problem in Argentina, where there is still a high number of candidates for each vacancy.5 In contrast, the process of feminization of the student body in Argentina, which reaches 70%,23 should be taken into account when attempting to make the specialty of surgery more attractive for potential candidates.

Among the limitations of this study is the fact that, as the students surveyed were doing surgery coursework, their opinions could be biased as they may have “sympathized” with the subject matter. A control group of students who were not currently studying surgery, or had already done so, could have generated different opinions and results. On the other hand, with this design, the opinions of the students about surgery did not necessarily link with the decision to choose the specialty or not; only a cohort study could have demonstrated this association.

In conclusion, the lack of interest for choosing surgery as a specialty could be fundamentally related with lifestyle aspects or the quality of life of surgeons, more so than with other conditions such as job opportunities, remuneration or prestige. Some characteristics of surgeons, such as a perceived self-sufficiency or a presumably limited doctor–patient relationship, could also pay an influential role when choosing the specialty. Likewise, female residents could be equally as interested as males in practicing surgery, a fact that should be highlighted when we consider that the surgical specialties have traditionally been dominated by men. The fact that the surgeons in our study have coincided with most of the student opinions would require their function as role models to be reviewed in order to promote interest in surgery as a vocation.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare having no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Borracci RA, Ferraina P, Arribalzaga EB, Poveda Camargo RL. Elegir a la cirugía como especialidad: Opiniones de los estudiantes de la Universidad de Buenos Aires sobre la cirugía y los cirujanos. Cir Esp. 2014;92:619–624.