Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is defined as a particular form of pancreatitis that often manifests as obstructive jaundice associated with a pancreatic mass or an obstructive bile duct lesion, and that has an excellent response to corticosteroid treatment. The prevalence of AIP worldwide is unknown, and it is considered as a rare entity. The clinical and radiological presentation of AIP can mimic bilio-pancreatic cancer, presenting difficulties for diagnosis and obliging the surgeon to balance decision-making between the potential risk presented by the misdiagnosis of a deadly disease against the desire to avoid unnecessary major surgery for a disease that responds effectively to corticosteroid treatment. In this review we detail the current and critical points for the diagnosis, classification and treatment for AIP, with a special emphasis on surgical series and the methods to differentiate between this pathology and bilio-pancreatic cancer.

La pancreatitis autoinmune (PAI) es una enfermedad fibroinflamatoria benigna del páncreas, se manifiesta frecuentemente como ictericia obstructiva asociada a masa pancreática o lesión obstructiva de la vía biliar y presenta una respuesta excelente a corticoides. Aunque no existen estudios a nivel mundial que definan su epidemiología, la PAI se considera una entidad poco frecuente, con una prevalencia estimada del 2% de los pacientes con pancreatitis crónica. Su frecuente presentación clínica y radiológica en forma de masa pancreática e ictericia similar al cáncer de páncreas y la falta de elementos diagnósticos específicos son causa de un elevado porcentaje de resecciones quirúrgicas pancreáticas por una enfermedad benigna que responde a tratamiento médico. En esta revisión detallamos los acuerdos actuales para el diagnóstico, clasificación y tratamiento de la PAI, enfatizando en las series quirúrgicas y en estrategias para mejorar el diagnóstico diferencial con el cáncer de páncreas y evitar así resecciones pancreáticas innecesarias.

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a benign fibro-inflammatory illness of the pancreas, reported for the first time in 1961 as a pancreatitis case related to hypergammaglobulinemia.1 In 1995, Yoshida et al. proposed the concept of AIP.2 Recently, the International Association of Pancreatology defined AIP as a specific form of pancreatitis that often manifests as obstructive jaundice, sometimes related to a pancreatic mass with characteristic histological changes that include lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and fibrosis, and shows an excellent response to cortico-steroid treatment.3

Types of Autoimmune PancreatitisHistopathological analysis of the pancreas defines 2 patterns with differential characteristics: (1) lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis (LPSP) or AIP without granulocyte epithelial lesions and (2) idiopathic duct centric pancreatitis (IDCP) or AIP with granulocyte epithelial lesions. However, given that the histological description is not always available, the terms type 1 and type 2 AIP have been introduced aiming to describe LPSP or IDCP related clinical manifestations, respectively.4

Type 1 pancreatitis is the predominant form in Asian countries. It is most frequent in males (3–4:1), peaking in the sixth decade of life; it may include elevation of serum immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4), and it is often related to fibroinflammatory involvement of other organs. Resolution of pancreatic and extrapancreatic manifestations with steroids is characteristic in type 1 patients, although relapse is frequent after treatment is stopped, in particular for cases with extrapancreatic involvement.5

Type 2 pancreatitis is reported more often in Europe and the United States. It affects mostly younger patients (one decade before type 1 AIP), without gender differences; it does not include IgG4 serum elevation, is not related to other organ involvement, and related inflammatory bowel disease exists in a high percentage of patients (11%–30%) (more frequently ulcerative colitis than Crohn's disease). Response to treatment with steroids is good and relapses are rare. Given that type 2 AIP lacks serum markers (no IgG4 elevation) and other organ involvement, its definitive diagnosis requires a histological analysis of the pancreas. This explains in part why type 2 AIP is diagnosed less frequently than type 1.5

Clinical ManifestationsThe most frequent manifestation is obstructive jaundice caused by a pancreatic mass (up to 59% of cases) or by enlargement of the common bile duct wall.6 It may also appear as single or recurrent acute pancreatitis or progress into chronic pancreatitis with exocrine and endocrine pancreatic calcification and failure.7 Another form of presentation includes symptoms related to extrapancreatic involvement, for example: lacrimal or salivary tumour, cough, dyspnoea from pulmonary lesions or lumbago caused by retroperitoneal fibrosis or hydronephrosis.6

Histopathological ChangesAIP shows well-defined histopathological changes in the pancreas that are easily differentiated from changes occurring in other types of pancreatitis (alcoholic or chronic obstructive). Some of these types are common findings for type 1 and type 2 and others are used to differentiate both groups.8,9

Histopathological Findings Common to Type 1 and Type 2 Autoimmune PancreatitisLymphoplasmacytic infiltration and inflammatory cellular stroma are highly characteristic findings of AIP.8 Lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is dense and becomes stronger around mid and large size ducts, compressing the ductal lumen (horseshoe or star shaped ductal image, highly characteristic of AIP) which differs from ductal dilation (characteristic of chronic pancreatitis from another origin). Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration extends diffusely through the pancreatic parenchyma, where it is accompanied by fibrosis and acinar atrophy and leads to inflammatory cellular stroma, with abundant lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophil patched areas; the latter are specific to AIP, however, not to other types of chronic pancreatitis.

Characteristic Findings of Type 1 Autoimmune PancreatitisStoriform fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis, prominent lymphoid follicles and IgG4+ plasma cells are findings highly characteristic of type 1 AIP, although they are also found in lower proportions in type 2.9 Storiform or whorled fibrosis is a peculiar type of fibrosis caused by a mesh of short collagen fibres intertwined in various directions and infiltrated by a dense lymphoplasmacytic component. This pattern is described in 90% of type 1 AIP and 29% of type 2 AIP. Obliterative phlebitis turns vein inflammation into lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, and then obstructs the vascular lumen. Although it is hard to recognise, its identification is of great interest because it is a pathognomonic sign of AIP. This change is described in 90% of type 1 AIP and 57% of type 2 AIP. The existence of prominent lymphoid aggregates and follicles in parenchyma and peripancreatic fat is another characteristic fact of AIP (100% for type 1 and 47% for type 2); however, it is also observed in approximately half of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis and obstructive chronic pancreatitis cases. Detecting abundant IgG4 plasma cells (>10cells/high power field [HPF]) is the key detail in diagnosing type 1 AIP, provided that for type 2 AIP no IgG4 plasma cells exist or are few in number (<10cells/HPF). It is important to consider that these cells can also be observed in other forms of chronic pancreatitis (11%–57%) and in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (12%–47%).

Characteristic Findings of Type 2 Autoimmune PancreatitisGranulocytic epithelial lesions are pathognomonic of type 2 AIP.9 These lesions are formed by neutrophil infiltrates affecting medium and small ducts, as well as acinar cells, causing cellular destruction and lumen obliteration.

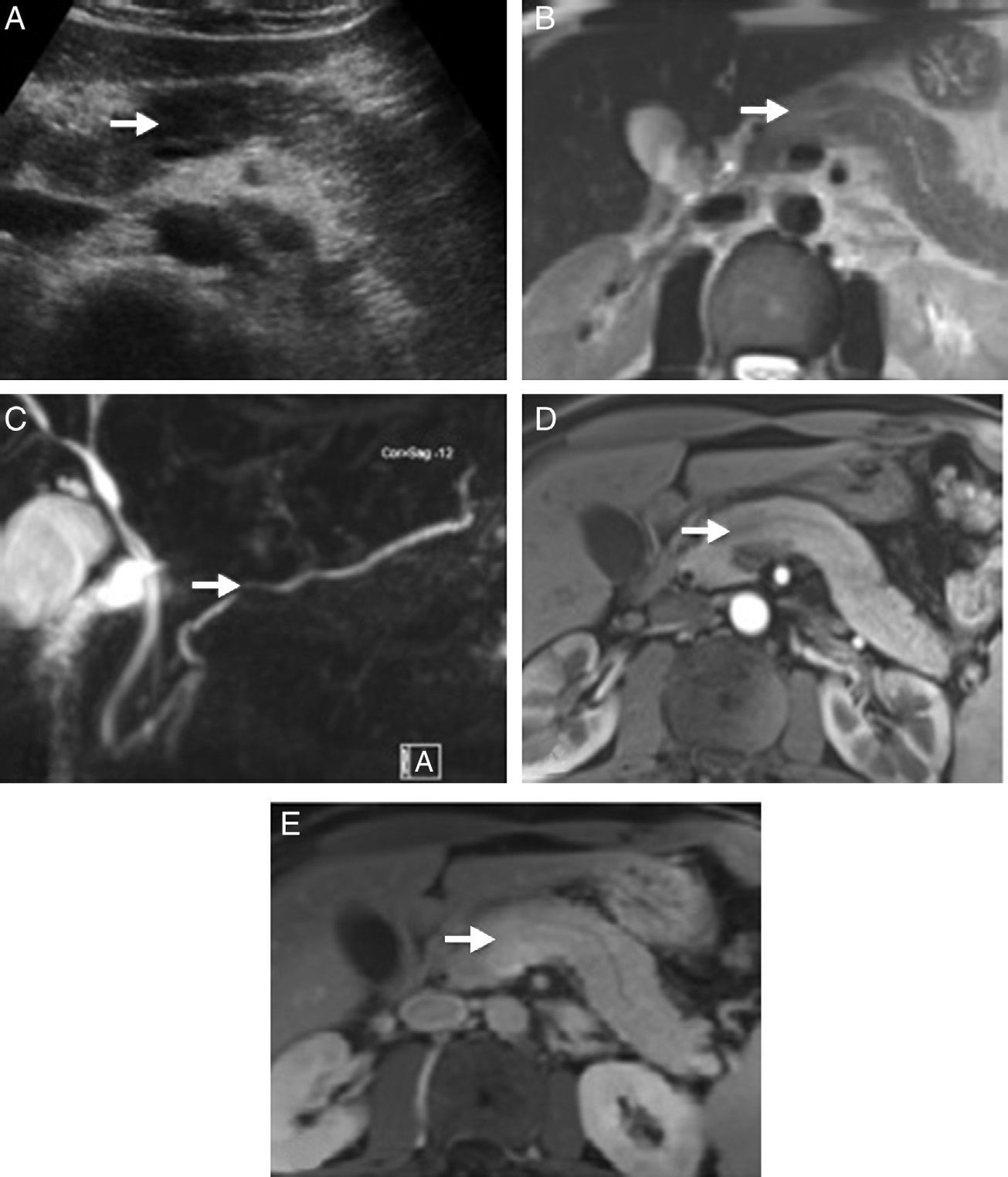

Imaging TestsTo diagnose AIP, we must look for typical parenchymatous and ductal changes, although, in many occasions, they are the same as those of pancreatic cancer.6 The typical image shows a diffusely shaped enlarged pancreas (“sausage-shaped pancreas”) with loss of lobularity. Parenchyma hypoattenuation in the pancreatic phase and delayed enhancement during the venous phase are characteristic in computerised axial tomography (CT). Magnetic resonance (MR) also shows characteristic hypointense pancreas enlargement in T1 potentiated sequences compared to an unaffected pancreas or compared to a hyperintense liver in T2 potentiated sequences and delayed enhancement in the venous phase. A hypoattenuated peripheral halo is a typical AIP finding with CT contrast and hypointense in MR T1 and T2 images. However, AIP can also show a focal, hypodense or hypointense pancreatic mass in CT and MR, respectively; these cases are the hardest to diagnose and differentiate from pancreatic cancer (Fig. 1). MR Wirsungraphy or endoscopic retrograde cholangiography may provide key information in terms of ductal changes. Long, multiple or focal stenosis is characteristic of AIP (>1/3 of the Wirsung conduct), all of this without proximal dilation.10 Endoscopy is another test of great value in AIP diagnosis, in particular because it offers the possibility of obtaining pancreatic cytology or biopsy for anatomopathological analysis.3,11,12

Radiological images of a pancreatic mass-shaped, painless jaundice-related autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) patient. (A) Abdominal ultrasound showing a hypoechoic focal area in the head of the pancreas compared to the rest of the gland. (B) Magnetic resonance scan T2 potentiated sequence showing a focal area with signal increase in the same area of the pancreas, lacking clear contour distortion and gland enlargement. (C) Cholangiographic sequences showing mild focal stenosis in pancreatic conduit size, which remains permeable and does not cause proximal dilation. (D) Pancreas focal area appears less emphasised than the adjacent parenchyma in the arterial phase of the dynamic analysis; (E) shows greater enhancement in delayed phases.

Currently, we lack specific serum markers to diagnose AIP. Serum IgG4 level elevation is a characteristic detail of type 1 AIP, although its interpretation deserves some considerations in terms of diagnostic sensitivity and specificity.13 Regarding sensitivity, type 2 AIP never includes IgG4 elevation, and a percentage of type 1 AIP patients are IgG4 negative.14 Its specificity is determined in great part by a set cut-off level, and it is important to consider that IgG4 may be elevated in other pancreatic diseases (in particular pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis), and extrapancreatic diseases (atopic dermatitis, asthma, pemphigus, parasitosis). If values above the upper level of normal (IgG4>135mg/dl) are considered positive, IgG4 sensitivity is limited (79%–93%),15,16 with 5% of the control subjects and 10% of pancreatic patients15 being positive. If the cut-off value is set for those greater than 2 times the normal level (IgG4>280mg/dl), none of the control subjects, and only 1% of pancreatic cancer patients show elevated IgG4, and marker specificity in these cases is 99%.15 As of now, we have no epidemiological data to define diagnostic accuracy for IgG4 in Spain, and data from several studies are too heterogeneous based on the geographical area (prevalent to a greater extent in Asian countries than in Europe), cut-off level or type of AIP analysed.13 Other parameters which may accompany AIP are hypergammaglobulinemia, IgG elevation, hypereosinophilia or the existence of anti-nuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor. Although these parameters can help confirm the diagnosis, none has been recognised within established diagnostic criteria by international criteria for AIP diagnosis.3

Other Organ InvolvementA total of 50%–70% of type 1 AIP patients experience other organ involvement as part of IgG4-related systemic disease.3,17,18 Extrapancreatic manifestations may precede, occur simultaneously or be subsequent to AIP. Diagnosis of other organ involvement may be conducted from histological involvement (IgG4 Plasma cell infiltration from the affected tissue), imaging (proximal bile duct stenosis, retroperitoneal fibrosis), clinical examination (salivary gland increase) and response to steroids.18,19 There is a large amount of tissue that may be affected; biliary tree involvement is the most frequent (50%–90% of cases) (IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis), which usually manifests as obstructive jaundice. Other possible sites include lymph nodes, salivary and tear glands, thyroid gland, retroperitoneum, gallbladder, liver, aorta, kidneys and ureter, breasts, lungs, central nervous system, and prostate. A characteristic shared by different involved organs in the context of IgG4-associated syndrome is the tendency to form tumefactive or pseudotumour lesions, histological lesions similar to those found in the pancreas, and although not always, serum IgG4 elevation. Other autoimmune disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, Sjögren syndrome) are not considered as “other organ involvement” disorders in AIP diagnosis.19

TreatmentTreatment aims to eliminate symptoms and resolve pancreatic and extrapancreatic manifestations observed in imaging tests.20 The treatment of choice is corticosteroids, given the good response both for type 1 and type 2 AIP, although recurrence after treatment termination is high, particularly for type 1 AIP.21 Albeit there is no standardised therapeutic protocol, most guidelines recommend prednisone at an initial dose of 35–40mg/day,22 or 0.6–1mg/kg/day according to international consensus for AIP diagnosis,3 during 4 weeks, and in the event of radiological and clinical response, a gradual dose reduction over 3–4 months. Some groups recommend maintaining low-dose steroid treatment (2.5–5mg/day) during 3 years for type 1 AIP, given its high rate of relapse.23 Reintroducing corticosteroids or starting immunosuppressors such as azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate, and rituximab are therapeutic alternatives used in the event of relapse after ending steroid treatment.20,24 Proximal stenosis relapse predictors include proximal biliary duct stenosis and persistent IgG4 elevation.20 Some patients, in particular those with type 2 AIP, experience spontaneous remission without steroid treatment.25

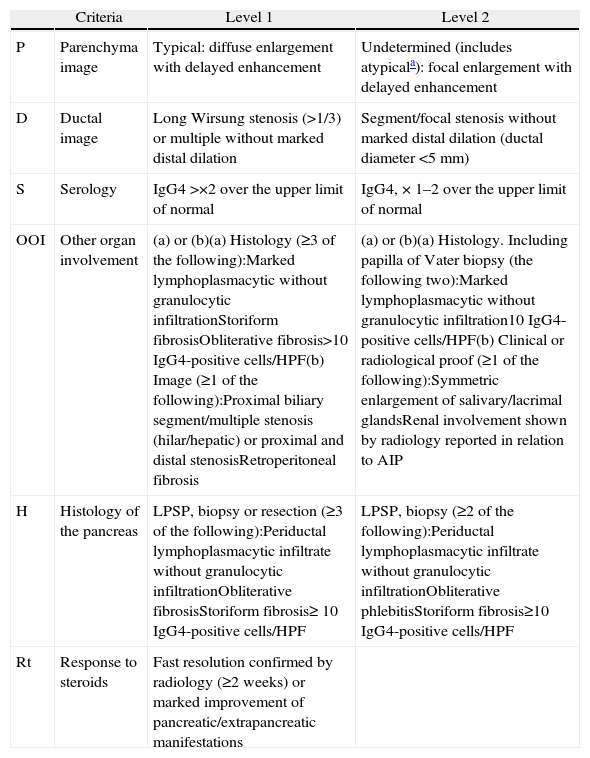

DiagnosisIn 2010, the International Association of Pancreatology developed the International Consensus on Diagnostic Criteria (ICDC) for AIP.3 This document consolidates diagnostic criteria defined previously by several associations (Japanese, Korean, Asian, Mayo Clinic, Mannheim, and Italian). ICDC establishes AIP diagnosis by combining one or more of the following aspects: (1) imaging findings: (a) from pancreatic parenchyma (by CT or MR), and (b) from the pancreatic duct (by MR cholangiography or endoscopic retrograde cholangiography); (2) Serology (IgG, IgG4, anti-nuclear antibodies); (3) other organ involvement; (4) pancreas histology and (5) response to corticosteroids. Each of these aspects are classified as level 1 and level 2 according to their diagnostic reliability. After applying these criteria, definite or probable diagnosis can be obtained for type 1 (Tables 1 and 2) or type 2 (Tables 2 and 3) AIP, although in some cases it is impossible to distinguish between the two types (undetermined autoimmune pancreatitis, Table 2).3

Classification of Level 1 and 2 Type 1 Autoimmune Pancreatitis Diagnostic Criteria.

| Criteria | Level 1 | Level 2 | |

| P | Parenchyma image | Typical: diffuse enlargement with delayed enhancement | Undetermined (includes atypicala): focal enlargement with delayed enhancement |

| D | Ductal image | Long Wirsung stenosis (>1/3) or multiple without marked distal dilation | Segment/focal stenosis without marked distal dilation (ductal diameter <5mm) |

| S | Serology | IgG4 >×2 over the upper limit of normal | IgG4, × 1–2 over the upper limit of normal |

| OOI | Other organ involvement | (a) or (b)(a) Histology (≥3 of the following):Marked lymphoplasmacytic without granulocytic infiltrationStoriform fibrosisObliterative fibrosis>10 IgG4-positive cells/HPF(b) Image (≥1 of the following):Proximal biliary segment/multiple stenosis (hilar/hepatic) or proximal and distal stenosisRetroperitoneal fibrosis | (a) or (b)(a) Histology. Including papilla of Vater biopsy (the following two):Marked lymphoplasmacytic without granulocytic infiltration10 IgG4-positive cells/HPF(b) Clinical or radiological proof (≥1 of the following):Symmetric enlargement of salivary/lacrimal glandsRenal involvement shown by radiology reported in relation to AIP |

| H | Histology of the pancreas | LPSP, biopsy or resection (≥3 of the following):Periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate without granulocytic infiltrationObliterative fibrosisStoriform fibrosis≥ 10 IgG4-positive cells/HPF | LPSP, biopsy (≥2 of the following):Periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate without granulocytic infiltrationObliterative phlebitisStoriform fibrosis≥10 IgG4-positive cells/HPF |

| Rt | Response to steroids | Fast resolution confirmed by radiology (≥2 weeks) or marked improvement of pancreatic/extrapancreatic manifestations |

HPF: high power field; AIP: autoimmune pancreatitis; LPSP: lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis.

Atypical: low density mass, ductal dilation or distal pancreatic atrophy. These atypical findings in a patient with obstructive jaundice are clearly suggestive of pancreatic cancer. These cases must be considered as pancreatic cancer unless strong collateral proof of AIP is available and an exhaustive diagnosis has been completed to rule out malignancy.

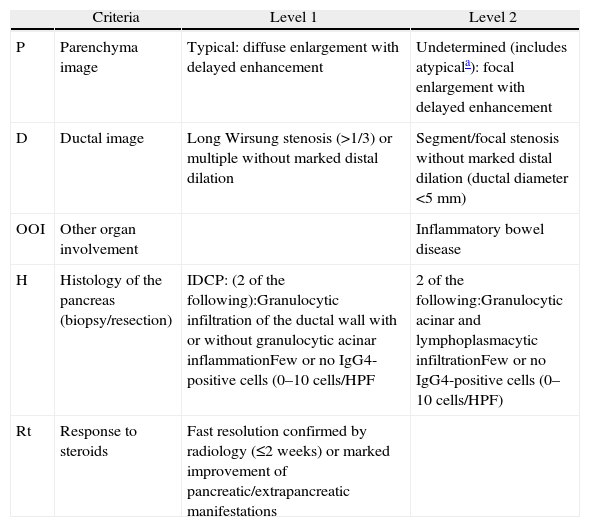

Classification of Level 1 and 2 Type 2 Autoimmune Pancreatitis Diagnostic Criteria.

| Criteria | Level 1 | Level 2 | |

| P | Parenchyma image | Typical: diffuse enlargement with delayed enhancement | Undetermined (includes atypicala): focal enlargement with delayed enhancement |

| D | Ductal image | Long Wirsung stenosis (>1/3) or multiple without marked distal dilation | Segment/focal stenosis without marked distal dilation (ductal diameter <5mm) |

| OOI | Other organ involvement | Inflammatory bowel disease | |

| H | Histology of the pancreas (biopsy/resection) | IDCP: (2 of the following):Granulocytic infiltration of the ductal wall with or without granulocytic acinar inflammationFew or no IgG4-positive cells (0–10cells/HPF | 2 of the following:Granulocytic acinar and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrationFew or no IgG4-positive cells (0–10cells/HPF) |

| Rt | Response to steroids | Fast resolution confirmed by radiology (≤2 weeks) or marked improvement of pancreatic/extrapancreatic manifestations |

HPF: high power field; IDCP: idiopathic duct-centric pancreatitis.

Atypical: low density mass, ductal dilation or distal pancreatic atrophy. These atypical findings in a patient with obstructive jaundice are clearly suggestive of pancreatic cancer. These cases must be considered as pancreatic cancer unless strong collateral proof of AIP is available and an exhaustive diagnosis has been completed to rule out malignancy.

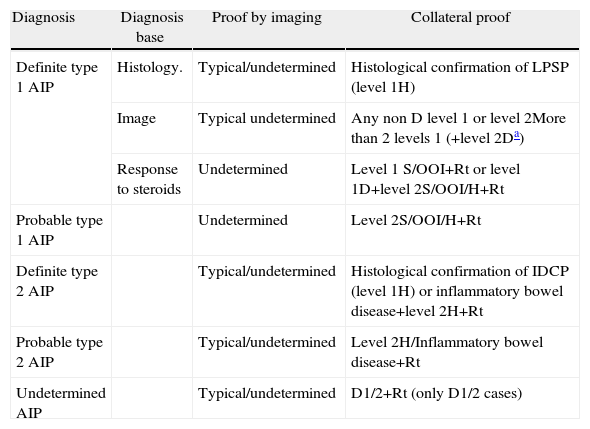

Definite, Probable or Undetermined Diagnosis of Type 1 and Type 2 Autoimmune Pancreatitis.

| Diagnosis | Diagnosis base | Proof by imaging | Collateral proof |

| Definite type 1 AIP | Histology. | Typical/undetermined | Histological confirmation of LPSP (level 1H) |

| Image | Typical undetermined | Any non D level 1 or level 2More than 2 levels 1 (+level 2Da) | |

| Response to steroids | Undetermined | Level 1 S/OOI+Rt or level 1D+level 2S/OOI/H+Rt | |

| Probable type 1 AIP | Undetermined | Level 2S/OOI/H+Rt | |

| Definite type 2 AIP | Typical/undetermined | Histological confirmation of IDCP (level 1H) or inflammatory bowel disease+level 2H+Rt | |

| Probable type 2 AIP | Typical/undetermined | Level 2H/Inflammatory bowel disease+Rt | |

| Undetermined AIP | Typical/undetermined | D1/2+Rt (only D1/2 cases) |

OOI: other organ involvement; D: ductal image; H: histology of the pancreas; AIP: autoimmune pancreatitis; IDCP: idiopathic duct-centric pancreatitis; LPSP: lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis; Rt: response to steroids; S: serology.

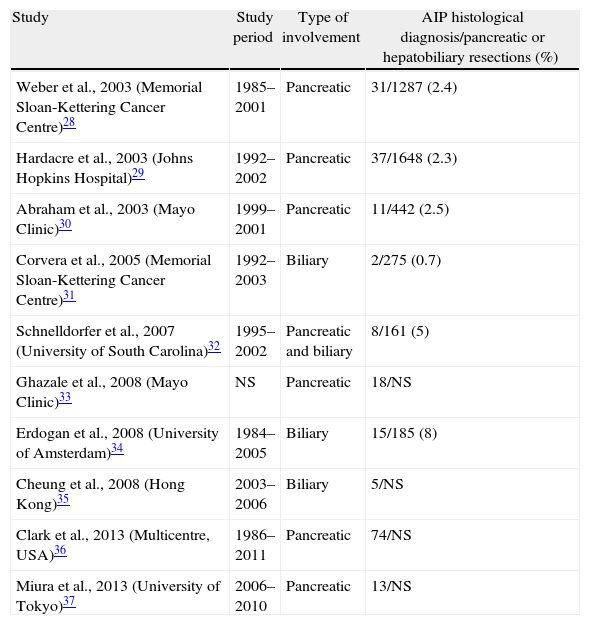

AIP prevalence in Western and Eastern countries is unknown. In Japan, a prevalence of 0.82 per 100000 inhabitants is estimated, and 6% of chronic pancreatitis patients in the United States will have AIP, which places AIP as a rare disease (those with a prevalence of <5 cases/100000 inhabitants).26,27 However, despite being so rare, a differential diagnosis of AIP with pancreatic or biliary neoplasia is fundamental, given that its prognosis and offered treatment are radically different. Clinical and radiological presentation, often indistinguishable from biliopancreatic neoplasia, and the lack of a definitive marker lead to diagnostic undervaluation of this disease, which leads to unnecessary pancreatic resections in a considerable number of cases. Surgical case series studies published thus far carry great scientific value, since they are a starting point to recognise and describe AIP histological lesions, demonstrate the difficulty of its diagnosis and show us the need to have a greater level of awareness and knowledge of the existence of this disease to be able to reach its diagnosis before indicating surgery (Table 4).28–37

Autoimmune Pancreatitis Surgical Case Series.

| Study | Study period | Type of involvement | AIP histological diagnosis/pancreatic or hepatobiliary resections (%) |

| Weber et al., 2003 (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre)28 | 1985–2001 | Pancreatic | 31/1287 (2.4) |

| Hardacre et al., 2003 (Johns Hopkins Hospital)29 | 1992–2002 | Pancreatic | 37/1648 (2.3) |

| Abraham et al., 2003 (Mayo Clinic)30 | 1999–2001 | Pancreatic | 11/442 (2.5) |

| Corvera et al., 2005 (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre)31 | 1992–2003 | Biliary | 2/275 (0.7) |

| Schnelldorfer et al., 2007 (University of South Carolina)32 | 1995–2002 | Pancreatic and biliary | 8/161 (5) |

| Ghazale et al., 2008 (Mayo Clinic)33 | NS | Pancreatic | 18/NS |

| Erdogan et al., 2008 (University of Amsterdam)34 | 1984–2005 | Biliary | 15/185 (8) |

| Cheung et al., 2008 (Hong Kong)35 | 2003–2006 | Biliary | 5/NS |

| Clark et al., 2013 (Multicentre, USA)36 | 1986–2011 | Pancreatic | 74/NS |

| Miura et al., 2013 (University of Tokyo)37 | 2006–2010 | Pancreatic | 13/NS |

Ratio of patients diagnosed with AIP after histological analysis of the sample for patients who underwent surgery due to suspicion of biliopancreatic neoplasia.

NS: not specified; AIP: autoimmune pancreatitis.

The most frequent clinical manifestation of AIP, in particular type 1, is painless obstructive jaundice related to a pancreatic mass (68%–84%),28,29,38 and the biliary ducts are the most frequent extrapancreatic involvement site.6,39 In many cases, a pancreatic head mass lesion and involvement of the distal biliary duct caused by AIP produce symptoms matching pancreatic cancer. In the event of proximal biliary involvement, hilar cholangiocarcinoma may be suspected.34

Three major surgical case series have been published describing AIP cases in a large number of patients who underwent pancreatic resection. These are: Weber et al. at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre in New York, Hardacre et al. at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, and Abraham et al. at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota (Table 4).28–30 The Weber study comprises 1287 pancreatic resections carried out from 1985 to 2001.28 A total of 159 (12%) of them had benign illness during anatomopathological assessment, of which 29 were autoimmune pancreatitis, and 2 patients suffered pseudotumours related to AIP that were considered non-resectable. These 31 patients represent 2.7% of the total operated-on patients and 19.5% of operated-on patients with benign disease. Mean age for these 31 patients was 62 years; 68% were male; 68% had jaundice, 29% abdominal pain and 19% “autoimmune related disease”. Resections were: 23 duodenopancreatectomies (DP), 4 distal pancreatectomies, and 2 total pancreatectomies. Two patients were non-resectable due to upper mesenteric artery and portal vein infiltration. Eight of the 29 patients (28%) experienced “relapse” of the disease and 3 of the 4 patients with distal resection developed subsequent jaundice. Four of the 23 patients with DP developed jaundice after excision (3 resulting from multiple intrahepatic stenosis and one from bilioenteric anastomosis), and one of the 23 CDP developed pancreatitis from pancreatic ductal stenosis.28 This study highlights the difficulty of reaching correct AIP diagnosis before surgery and how a third of patients experienced disease relapse after excision; this highlights the need for post-surgical treatment of these patients.

A total of 1648 duodenal pancreatic resection cases at the Johns Hopkins hospital conducted between 1992 and 2002 were reviewed.29 Of these, 176 (11%) resulted from chronic pancreatitis, of which 37 cases (21%) were related to AIP. All AIP patients were suspected of pancreatic cancer prior to surgery and all were resectable. Mean age for these patients was 62 years; 64% were male; 84% had jaundice, 54% abdominal pain, and 34% autoimmune related disease. The type of surgery was 26 pylorus-preserving DP and 11 classic DP.29

In their review, Abraham et al., at the Mayo Clinic, evaluated 442 CDP samples performed from 1999 to 2001.30 This case series identified 47 neoplastic disease-negative samples (10.6%), and from these, 40 patients underwent surgery due to suspicion of malignancy (9.2%). The clinical characteristics that raised suspicion of malignancy in these 40 cases were pancreatic mass lesions in 67%, obstructive jaundice in 50%, stenosis of the biliary pathways in 40%, and positive cytology in 12% of patients. Definite pathological diagnosis of these 40 patients was AIP in 11 (27.5%), alcohol-related chronic pancreatitis in 8 (20%), biliary lithiasis-related pancreatitis in 4 (10%), chronic pancreatitis of undetermined aetiology in 6 (15%), isolated biliary pathway stenosis of undetermined aetiology in 4 patients (10%), and sclerosing cholangitis in 3 patients (7.5%). This study revealed that the number of CDP from benign pancreas disease is significant (9.2%) and that AIP is the most frequent diagnosis amongst them.30

Accumulated surgical experience in patients with AIP has shown the technical difficulties involved in pancreatic surgery for these patients, which the surgeon must take into account to avoid vascular lesion and bleeding problems. AIP patients require longer surgery time, and they experience greater blood loss probably caused by more difficult dissection of the sample for separation of visceral vessels due to peripancreatic inflammation and disfiguration of planes in normal tissue.28–30,40 Recently, Clark et al. published a report on short-term and long-term surgical experience from a multicentre study including AIP patients at the Mayo Clinic (Minnesota and Florida sites) and at the Massachusetts General Hospital from 1986 to 2011.36 A total of 74 AIP patients were recruited for this study, diagnosed by histology in pancreatic samples collected after surgical resection. Mean age of patients was 60 years; 69% were male, and the surgery indication was suspected cancer in 80% of them. AIP subtype was determined in 63 (85%) of the patients; a total of 34 were type 1, and 29 type 2. Surgeries performed were: DP in 56 patients (75%), distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy in 10 patients (14%), without splenectomy in 5 patients (7%), and total pancreatectomy in 3 patients (4%). The most frequent cause for surgery was suspected neoplasia (n=59, 80%). This study describes surgical difficulties in 34 patients (46%). Vascular repair/reconstruction was needed in 15 (20%) of patients; mean (interquartile range) surgery time was 360min (325–415min), and 19 (26%) of patients required blood transfusion in the first 24 postoperative hours. Estimated blood loss was 600ml (300–1000ml), and 4% needed resurgery in the first 30 days (3 patients). Ten (14%) patients experienced major complications; there was one perioperative death (1%), and 2 patients had clinically significant pancreatic fistulas (ISGPF grade B/C). A total of 17% of the patients experienced AIP symptom recurrence without significantly affecting their overall survival. These studies revealed the intraoperative technical difficulties and the additional surgical challenge posed by this condition.

Final CommentDespite growing knowledge about AIP gathered in recent years, AIP remains a disease with delayed diagnosis after pancreatic resection. A retrospective study conducted by Learn et al. in a case series involving 68 patients diagnosed with AIP shows that 53 of them underwent pancreatic resection as a first therapeutic option, and 15 of them did not undergo surgery. Compared to patients who did not undergo surgery, the group of patients who did showed a lower rate of diffuse pancreatic enlargement (80% vs 8%, respectively) and a smaller amount of serum IgG4 analysis pre-treatment (100% vs 11%). Puncture cytology was interpreted incorrectly as adenocarcinoma in 12 patients, of whom 10 underwent surgery. This study concludes that the factors leading to pancreatic resection in AIP patients from incorrect diagnosis include: difficulty in recognizing details specific to the disease, such as characteristic radiological manifestations, and false positives from endoscopic cytology (33). The main limiting factor for this test is the small volume of biopsy that can be collected; therefore, unless it is performed by experienced endoscopists, generally it cannot be used for definitive AIP diagnosis.41,42

Currently, there is an imperative need for developing serum markers or imaging tests able to easily and accurately identify the disease; otherwise, we need to focus on developing strategies to try to provide a differential diagnosis with pancreatic cancer by combining diagnostic elements.43–46 Along this line, international diagnostic criteria have been set forth to have a systematised diagnostic consensus for these patients.3 In most cases, proof of a head of pancreas hypointense mass in an obstructive jaundice patient will leave no doubt regarding pancreatic cancer diagnosis. However, it is important to reconsider the diagnosis if atypical findings occur, such as atypical clinical course, other organ involvement, existence of peripheral halo in the pancreatic mass, lack of prestenotic ductal dilation or serum IgG4 level elevation during diagnosis. One of the diagnostic items recognised by CIDC is response to corticosteroids. This is a tool that can be considered when pancreatic cancer has been excluded: for example, with atypical pancreatic masses shown by radiological imaging and negative cytology for malignant cells. For these cases an initial 2-week treatment is recommended, then a reassessment of the patient's symptoms and radiological manifestations.47 Evidence reported on pancreatic adenocarcinoma cases in AIP patients should be mentioned,48,49 as well as on intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia,50,51 which highlights the need to provide close follow-up for these patients.

Conflict of InterestsAuthors declare having no conflict of interest.