Chylous leakage is a rare complication after major abdominal operations and is characterized by the collection of chylous fluid in the peritoneal cavity. Postoperative chylous leakage mainly develops as a result of surgical trauma to lymphatic channels such as lacteals, tributaries or the main lymphatic duct itself and cysterna chyli. It could be either a localized chylous leakage or diffused chylous peritoneum. The surgical procedures reported to be associated with chylous leakage are mainly the ones involving retroperitoneal dissection such as testicular cancer,1 pancreatic resection,2 abdominal aortic surgery,3 and gastric cancer with D3 dissection.4 Since it is an unusual complication, the true incidence, natural history and the proper treatment algorithms remain to be defined. The delay in treatment or mismanagement may lead to dire consequences such as loss of fluid, proteins, fats, lymphocytes and subsequent cachexia.1 Although a few number of cases with chylous leakage after colorectal resection have been reported,5,6 neither the incidence nor the associated factors have been stated. Here we present the management of our four cases with chylous leakage after colorectal resection.

Between June 2004 and April 2010, all patients who underwent colorectal resection for cancer in Vakif Gureba Training and Research Hospital were prospectively collected in a database approved by our hospital institutional board. Informed consents were obtained from all patients. A postoperative early recovery protocol was adopted from 2006, and oral feeding was started from postoperative day 1 with clear liquids. By the third day, colorectal cancer patients received normal diet with minimal fiber content. Like colorectal cancer patients, oral feeding for gastric cancer patients was started from postoperative day 1 with clear liquids. Chylous leakage was suspected postoperatively when a milky-appearing drain effluent was observed. The diagnosis of chylous leakage was confirmed by the triglyceride level of >110mg/dl in drain fluid. All patients underwent total parenteral nutrition immediately after the diagnosis. With the cessation of fluid drainage, patients started oral feeding with a low-fat containing diet. Before hospital discharge they resumed normal oral feeding including fats. The demographic data, clinical presentation, primary diagnosis, type and extent of surgery, tumor characteristics and stage, number of harvested lymph nodes, the drain fluid characteristics, the duration of effusion, management and complications were all noted.

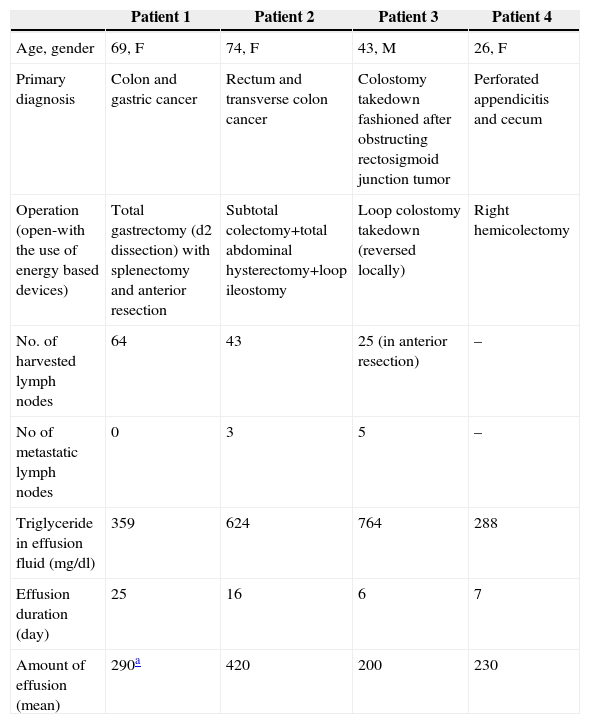

During the specified period, 273 colorectal resections were performed in our unit. Both open and laparoscopic resections and rarely combined other-organ resections (especially gastric) were performed. Three female and one male patient with chyloperitoneum were identified. The incidence of chyloperitoneum after colorectal resections was 1.46% (4/273). Of four patients, three underwent colorectal resection for malignant causes. In one patient, the chylous leakage was noticed after colostomy takedown where the colostomy had been fashioned earlier for obstructing rectosigmoid cancer. At follow-up period (before takedown operation) CT scan did not identify any abdominal collection and no chylous fluid was present at operation. Two patients had synchronous tumors resulting in multivisceral resections and two patients had radiotherapy before the operation. The only patient without tumor was a female patient with delayed perforated appendicitis. On exploration, both appendix and cecum were found to be perforated due to massive intraabdominal inflammation and necrosis. One patient (patient no 1) underwent percutaneous catheter placement under ultrasonographic guidance for an intraabdominal collection due to premature drain removal. The drain fluid was contaminated with gram-negative bacteria and the patient treated with appropriate antibiotics. Two patients (patient no. 1–4) had wound infections. No postoperative mortality was observed. The demographic features, characteristics of fluid, diagnosis and treatment of patients, are presented in Table 1.

Characteristics of the Patients With Chylous Leakage.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, gender | 69, F | 74, F | 43, M | 26, F |

| Primary diagnosis | Colon and gastric cancer | Rectum and transverse colon cancer | Colostomy takedown fashioned after obstructing rectosigmoid junction tumor | Perforated appendicitis and cecum |

| Operation (open-with the use of energy based devices) | Total gastrectomy (d2 dissection) with splenectomy and anterior resection | Subtotal colectomy+total abdominal hysterectomy+loop ileostomy | Loop colostomy takedown (reversed locally) | Right hemicolectomy |

| No. of harvested lymph nodes | 64 | 43 | 25 (in anterior resection) | – |

| No of metastatic lymph nodes | 0 | 3 | 5 | – |

| Triglyceride in effusion fluid (mg/dl) | 359 | 624 | 764 | 288 |

| Effusion duration (day) | 25 | 16 | 6 | 7 |

| Amount of effusion (mean) | 290a | 420 | 200 | 230 |

Chyloperitoneum is the collection of lymphatic fluid in the peritoneal cavity and may result from disruption of normal lymphatic circulation by obstruction, injury, or exudation through the walls of lymphatics. The most common causes in adults are intraabdominal malignancies like lymphoma, ovarian and prostate cancers obstructing the lymphatic vessels at the base of mesentery or retroperitoneum.7 Since the major lymphatics ascend through the aorta retroperitoneally, the operations involving the retroperitoneum such as abdominal aortic aneurysm,3 testicular cancers with retroperitoneal lymph node dissection,1 gastric surgery with D3 dissection4 and pancreatic surgery2 carry increased risk for postoperative chylous leakage. Although cisterna chyli seems to be more consistent at its presumed location, the contributing lymphatics vary widely in shape, orientation, and size.1,3 Hence, the anatomical variations could also be a contributing factor for the injury to lymphatics responsible for the chyloperitoneum.

The true incidence of chylous leakage is not well documented. An earlier study reported overall incidence of 1 in 20,000 after major abdominal procedures. Higher figures ranging from 1.3% to 7% after specific surgical procedures were published later.1,2 The reported incidences of chylous leakage after retroperitoneal dissection for testicular cancer varied between 2% and 7%.1,8 In a recent well-documented study with more than 3500 patients who underwent pancreatic resection, the incidence of chylous leakage was noted as 1.3%.2 The chylous leakage after colorectal resection was noticed as rare incidences.5,6 In our series, the incidence of chylous leakage was found to be 1.46%. However this incidence (either purely or combined colorectal cases) should be taken with caution since the number of patients in our series is quite small.

Many predictive factors have been associated with higher risk of postoperative chylous leakage including the number of harvested lymph nodes, history of concomitant vascular resection, preoperative chemotherapy and intraoperative blood loss.1,2 Earlier reports have shown that extensive lymphadenectomy with testicular cancer,1 gastrectomy,4 and pancreatectomy2 was associated with an increased risk of chylous leakage. Each of our patients had at least one of the acknowledged predisposing factors for chyloperitoneum in the literature. Indeed, two patients had synchronous tumors of gastric and rectal cancers that required a wide excision involving potential sites of injury like lymphatic tributaries present in the retroperitoneum around the celiac axis and the root of inferior mesenteric vein. Both patients had increased number of lymph nodes (n: 64 and n: 43) harvested during their surgery. Only our third patient received chemoradiotherapy prior to operation (colostomy closure in patient with Hartmann resection due to obstructing rectosigmoid tumor one year before). The reason for chylous leakage could either be due to the damage to intestinal lymphatics after chemoradiotherapy or the injury of lymphatic tributaries during colostomy takedown due to the dissection of dense adhesions. The last patient had a delayed perforated appendicitis complicated with perforation of the cecum. She had an inflammatory mass involving both retroperitoneum and abdomen resulting in right hemicolectomy.

An algorithm based on a step-wise management of chylous leakage has been proposed to decrease the lymph production while maintaining nutritional balance.9 Starting with conservative measures like dietary regulation, total parenteral nutrition and continuing with more aggressive approaches including surgery were advocated as the main measures of treatment. Most studies have reported 75%–85% success rate of treatment with conservative methods.1,2,6,8–10 We managed to treat all our patients conservatively by starting total parenteral nutrition with fasting to allow bowel rest and reduce the lymph flow early after detection of chylous fistula. After controlling the fistula, oral diet was commenced with a fat-free diet. Although some investigators reserved TPN for patients in whom previous conservative measures like dietary restriction with medium-chain triglycerides failed, the others used TPN early in the management.1,8 The use of long-acting somatostatin analogs has been suggested since the reported success rate as an adjunct to other conservative measures is satisfactory.10 Although we have not used octreotide due to successful management of fistula in relatively short time (mean duration of fistula was less than 2 weeks for our patients), it could be considered in refractory or high-output fistula cases before surgical options. In conclusion, nonoperative management was a successful management in our experience.

Contribution of the Authors to the Manuscript- 1.

Conception and design: AI, IO

- 2.

Acquisition of data: DF, OI

- 3.

Analysis and interpretation of data: AI, IO

- 4.

Drafting the article: IO

- 5.

Critical revision: AI

- 6.

Final approval of the manuscript: AI, IO, DF, OI

The autors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Isik A, Okan I, Firat D, Idiz O. Una complicación muy poco frecuente de la cirugía colorrectal y su tratamiento: fuga quilosa. Cir Esp. 2015;93:118–120.