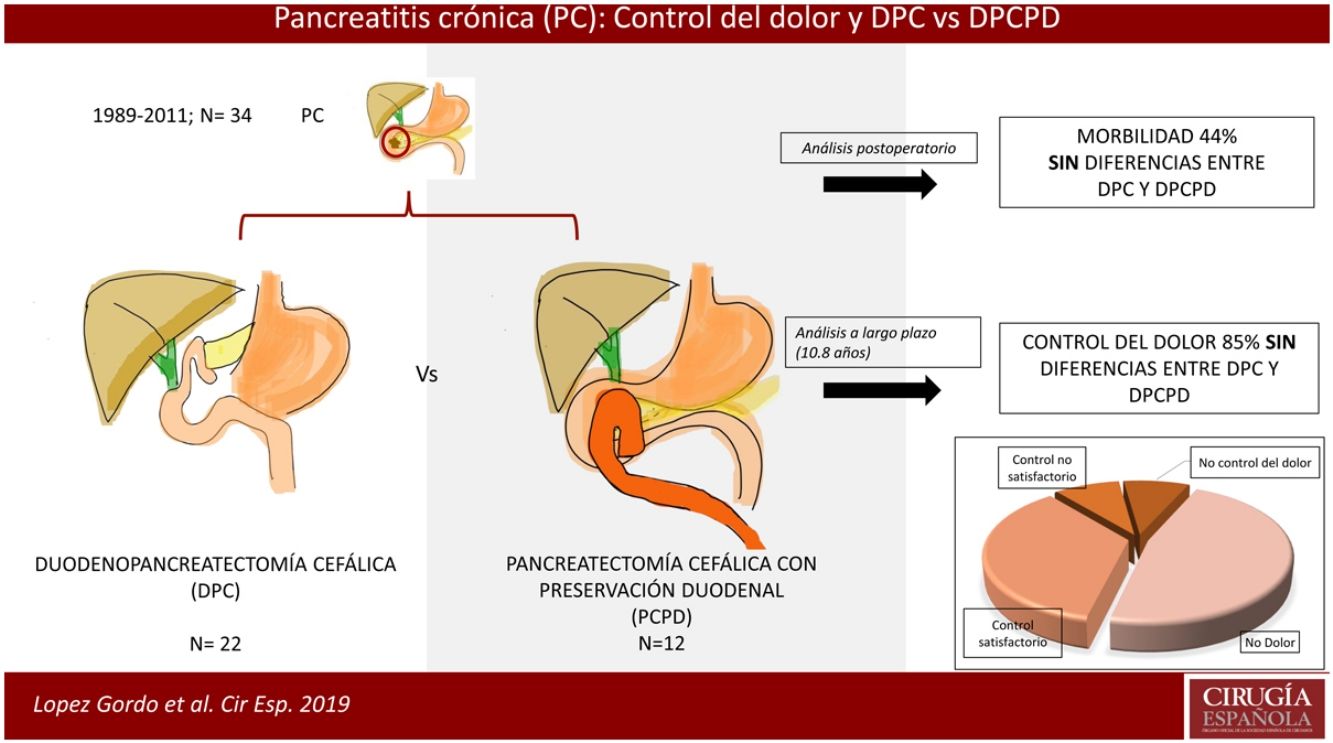

Chronic pain in chronic pancreatitis is difficult to manage. The objective of our study is to assess the control of pain that is refractory to medical treatment in patients with an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas, as well as to compare the two surgical techniques.

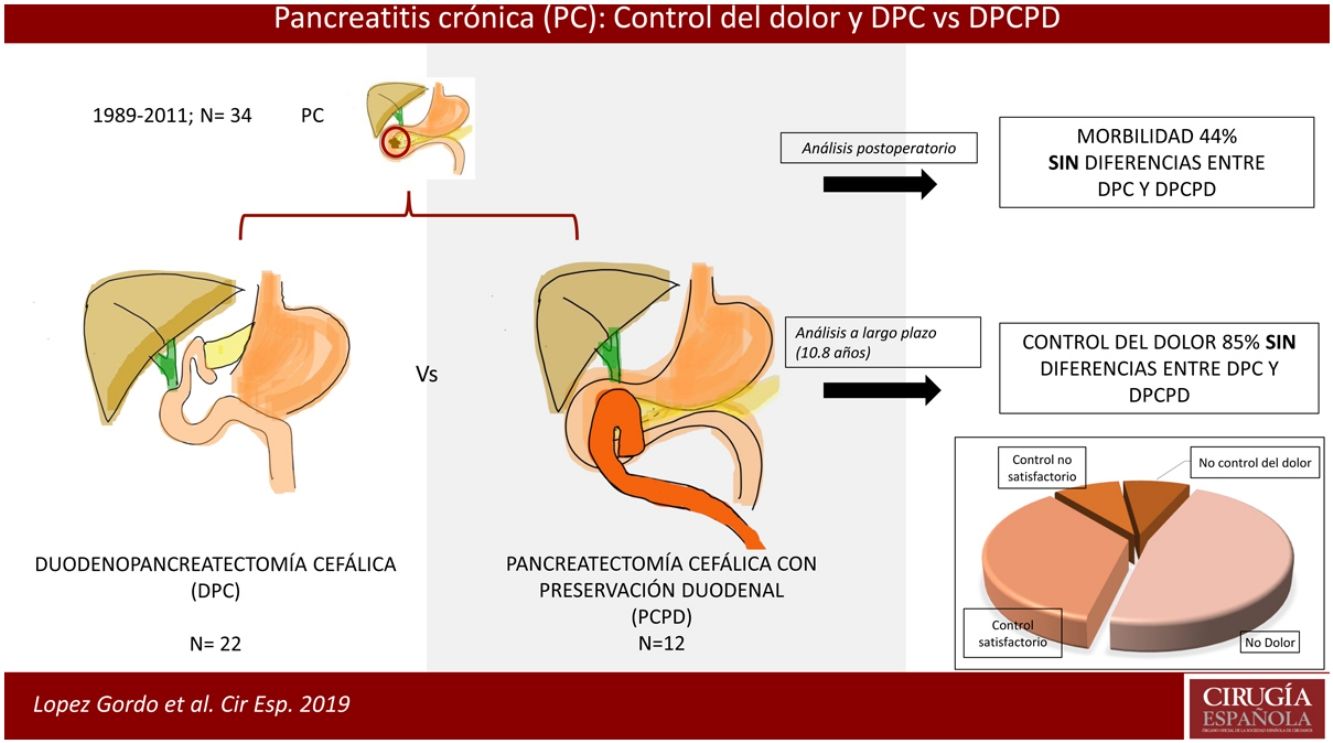

MethodsA retrospective study included patients treated surgically between 1989 and 2011 who had been refractory to medical treatment with inflammation of the head of the pancreas. An analysis of the short and long-term results was done to compare patients who had undergone pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) and/or resection of the head of the pancreas with duodenal preservation (RHPDP).

Results22 PD and 12 RHPDP were performed. Postoperative complications were observed in 14% of patients, the most frequent being delayed gastric emptying (14.7%) and pancreatic fistula (11.7%). No statistically significant differences were found in terms of surgical technique. Pain control was satisfactory in 85% of patients, 43% presented de novo diabetes mellitus, and 88% returned to their work activities. Fourteen patients died during follow-up, 7 due to malignancies, and some were related to tobacco use and alcohol consumption. The overall 5 and 10 year survival rates were 88% and 75% respectively.

ConclusionCephalic resection in patients with intractable pain in chronic pancreatitis is an effective therapy that provides good long-term results in terms of pain control, with no significant differences between the two surgical techniques. Patients with chronic pancreatitis have a high mortality rate associated with de novo malignancies.

El dolor crónico en la pancreatitis crónica es de difícil manejo. El objetivo de nuestro trabajo es la valoración del control del dolor refractario al tratamiento médico en pacientes afectos de masa inflamatoria en la cabeza pancreática, así como comparar dos técnicas quirúrgicas realizadas.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo sobre pacientes intervenidos entre 1989 y 2011 refractarios al tratamiento médico con predominio inflamatorio en la cabeza pancreática. Se realizó un estudio comparativo a corto y a largo plazo entre los pacientes intervenidos mediante duodenopancreatectomía cefálica (DPC) y/o pancreatectomía cefálica con preservación duodenal (PCPD).

ResultadosSe realizaron 22 DPC y 12 PCPD. En el 44% de los casos se presentaron complicaciones posquirúrgicas, siendo las más frecuentes el vaciamiento gástrico retardado (14,7%) y la fístula pancreática (11,7%). No se evidenciaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas según la técnica quirúrgica. Se consiguió el control del dolor de forma satisfactoria en el 85% de los pacientes, hubo un 43% de diabetes mellitus de novo, y la reincorporación a la actividad laboral fue del 88%. Catorce pacientes fallecieron durante el seguimiento; de ellos, 7 a causa de neoplasias, algunas de ellas relacionadas con el consumo de tabaco y alcohol. La supervivencia global a 5 y 10 años fue del 88 y del 75%, respectivamente.

ConclusiónLa resección cefálica en pacientes con dolor intratable en la pancreatitis crónica es una terapéutica eficaz, con buenos resultados a largo plazo en términos de control del dolor y sin diferencias significativas entre ambas técnicas quirúrgicas. Los pacientes con pancreatitis crónica presentan una elevada mortalidad asociada a neoplasias de novo.

Chronic pancreatitis is an inflammatory disease of the pancreatic gland that is characterized by debilitating episodes of pain. In Spain, the annual incidence of chronic pancreatitis is between 5 and 14.4 cases/105 inhabitants/year.1 Pain control is one of the most important treatment challenges in these patients, involving a multidisciplinary approach with initial stepwise analgesic treatment.2

Historically, numerous surgical techniques have been described to alleviate the pain of chronic pancreatitis. Briefly, resection techniques stand out, basically pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD),3,4 which involves the removal of the inflammatory mass of the head of the pancreas, and the diversion techniques, mainly pancreaticojejunostomy,5 which entails bypassing the pancreatic duct to an intestinal loop. Later, other surgeons have devised mixed techniques, such as the Beger6 or Frey7 procedures, in which the pancreatic head was resected while preserving the duodenum, trying to minimize surgical risks, with good long-term results. Patients should undergo surgical techniques that are tailored for each case, depending on any morphological alterations.8

The main objective of this study is to assess the control of intractable pain in patients with inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas who underwent resection surgery, comparing the two surgical techniques performed.

MethodsInclusion CriteriaA retrospective study was conducted between December 1989 and December 2011, including patients diagnosed with predominantly inflammatory chronic pancreatitis in the head of the pancreas and whose surgical indication was pain. All patients underwent surgery at our hospital, performed by a team of surgeons with extensive experience in hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery. All patients met the definition of chronic pancreatitis accepted by the Cambridge International Workshop on Pancreatitis.9 We excluded from the study patients who required bypass surgery or in whom the pancreatic morphological lesion was centered in the body-tail region of the pancreas. Likewise excluded were those patients who underwent surgery for a suspected benign lesion but presented pancreatic cancer in the surgical specimen. No procedures were indicated in patients with chronic liver disease.

Preoperative Clinical EvaluationVarious preoperative clinical parameters were studied, such as age, sex, etiology, years of disease evolution, number of admissions, steatorrhea, diabetes mellitus (DM), weight loss, jaundice and vomiting. The analytical variables collected included bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase (AP) and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT). Morphological data recorded included the presence of cholelithiasis, calcifications of the pancreatic gland, Wirsung duct dilatation, bile duct dilatation, duodenal compression and pseudocysts. When there was history of endoscopic treatment, the type of procedure was recorded. Patients were classified according to the ASA classification (physical status classification system) of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Patients with severe hypoalbuminemia (<30g/dL) or severe hyperbilirubinemia (>300μmoL/L) underwent biliary drainage, and the procedure was delayed in order to improve their nutritional status.

After the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis with difficult pain management at our hospital, patients were referred to the Chronic Pain Unit, comprised of anesthesiologists. The WHO analgesic ladder was used, together with the administration of antidepressants as well as analgesics to enhance the action of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or weak opiates. Surgical intervention was considered necessary to improve pain in the event that, after analgesic optimization: (1) the patient continued to experience maintained, intractable, disabling pain or (2) the patient experienced episodes of severe pain (at least one per month with the need for opiates) for at least one year, after the failure of endoscopic therapy.

Surgical TreatmentThe indication for surgery of the patients analyzed was pain secondary to an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas. As we have commented, the surgical technique was individualized based on the clinical and morphological characteristics of the pancreatic lesion. Two surgical techniques for the head of the pancreas were analyzed. Initially, pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) was performed to treat these patients.10 Starting in 2002, duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (DPPHR)5 was introduced as the technique of choice. When it was necessary to act on the bile duct, we performed an associated hepaticojejunostomy.

Postoperative morbidity and mortality was analyzed according to the Dindo–Clavien classification.11 Pancreatic fistula and delayed gastric emptying were defined in accordance with the ISGPF criteria.12

Follow-upPatients were monitored through office visits or telephone consultations, and a questionnaire was used to assess patient progress. The first year, the office visits were scheduled every 6 months, and annually thereafter. Clinical changes (weight loss, appearance of DM and steatorrhea) and alcohol consumption were recorded. Occupational activity (work, occasional work, unemployed or disabled, and retired or with normal physical activity).

We defined 4 groups of patients, depending on the response to pain after surgery: total control, for patients without pain; satisfactory control, for patients with occasional pain and no need for opiates; unsatisfactory control, for patients with occasional pain and in need of opiates; and no control, for patients with continuous pain despite treatment with opiates. Lastly, the patients were divided into two groups: the controlled pain (CP) group, which included patients with total and satisfactory pain control; and the uncontrolled pain (UP) group, which included the sum of patients with unsatisfactory or no pain control.10

Patient assessment was annual, and patients who had not attended the follow-up visits had a telephone evaluation or were scheduled for an outpatient consultation in 2018. The study closed in March 2018.

Statistical AnalysisWe carried out a statistical analysis of the entire series, and it was subsequently divided according to the surgical technique (PD group and DPPHR group) for comparison. A descriptive analysis was performed for each of the continuous variables, calculating measures of central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion (standard deviation and range), and qualitative variables according to their percentage.

For the analysis of the quantitative variables of independent data, the non-parametric test or the Mann–Whitney U test was used; for the analysis of qualitative variables, the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test was used according to their normal distribution.

Survival was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Associations with a significance level of P≤.05 were considered significant. The statistical package used was the SPSS v.21.

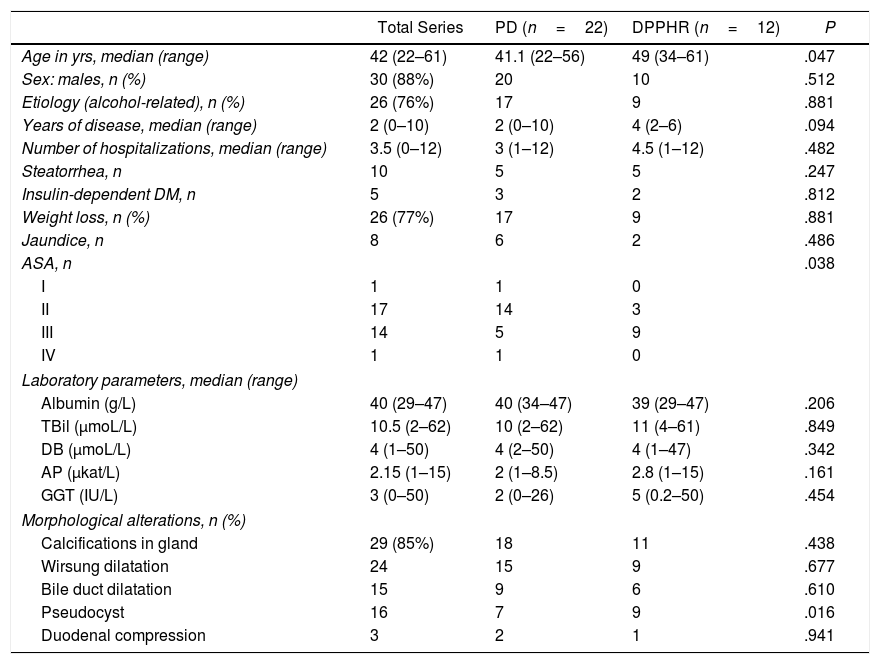

ResultsPreoperative Details, Surgical Intervention and Postoperative MorbidityThe study included 34 surgical patients, 88% of whom were males; mean age was 42 (22–61 years). The mean evolution of the disease was 2 years (0–10), with an average of 3.5 (0–12) admissions per patient during the study period (Table 1). Prior to surgery, 13 patients had undergone some type of endoscopic manipulation without success.

Preoperative Assessment.

| Total Series | PD (n=22) | DPPHR (n=12) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in yrs, median (range) | 42 (22–61) | 41.1 (22–56) | 49 (34–61) | .047 |

| Sex: males, n (%) | 30 (88%) | 20 | 10 | .512 |

| Etiology (alcohol-related), n (%) | 26 (76%) | 17 | 9 | .881 |

| Years of disease, median (range) | 2 (0–10) | 2 (0–10) | 4 (2–6) | .094 |

| Number of hospitalizations, median (range) | 3.5 (0–12) | 3 (1–12) | 4.5 (1–12) | .482 |

| Steatorrhea, n | 10 | 5 | 5 | .247 |

| Insulin-dependent DM, n | 5 | 3 | 2 | .812 |

| Weight loss, n (%) | 26 (77%) | 17 | 9 | .881 |

| Jaundice, n | 8 | 6 | 2 | .486 |

| ASA, n | .038 | |||

| I | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| II | 17 | 14 | 3 | |

| III | 14 | 5 | 9 | |

| IV | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Laboratory parameters, median (range) | ||||

| Albumin (g/L) | 40 (29–47) | 40 (34–47) | 39 (29–47) | .206 |

| TBil (μmoL/L) | 10.5 (2–62) | 10 (2–62) | 11 (4–61) | .849 |

| DB (μmoL/L) | 4 (1–50) | 4 (2–50) | 4 (1–47) | .342 |

| AP (μkat/L) | 2.15 (1–15) | 2 (1–8.5) | 2.8 (1–15) | .161 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 3 (0–50) | 2 (0–26) | 5 (0.2–50) | .454 |

| Morphological alterations, n (%) | ||||

| Calcifications in gland | 29 (85%) | 18 | 11 | .438 |

| Wirsung dilatation | 24 | 15 | 9 | .677 |

| Bile duct dilatation | 15 | 9 | 6 | .610 |

| Pseudocyst | 16 | 7 | 9 | .016 |

| Duodenal compression | 3 | 2 | 1 | .941 |

DB: direct bilirubin; TBil: total bilirubin; DM: diabetes mellitus; PD: pancreaticoduodenectomy; AP: alkaline phosphatase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; n: number of cases; DPPHR: duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection.

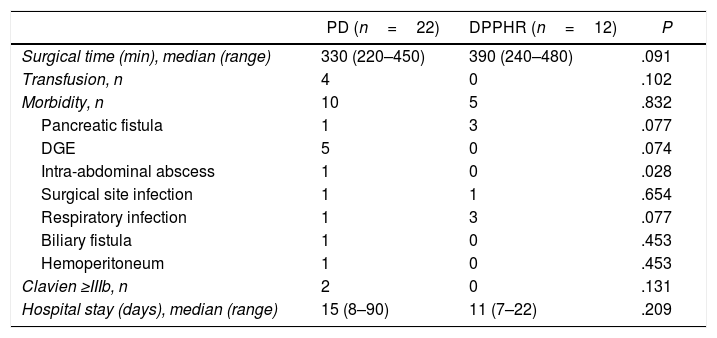

During the period studied, 22 PD and 12 DPPHR were performed. However, since 2002 the technique of choice has been DPPHR, so only two patients underwent PD: one because of previous gastric surgery, and the other due to technical impediments to perform a DPPHR during the course of surgery. Overall mortality (Clavien V) was 3% and overall morbidity 44%. Most complications were Clavien I and II, with no statistically significant differences between the two techniques. Nonetheless, we observed a greater number of intra-abdominal abscesses in the PD group (P=.028; Table 2), yet only one patient required percutaneous drainage (Clavien IIIa). Two patients in the PD group were reoperated (Clavien IIIb). The first patient had an intraoperative lesion of the superior mesenteric vein as a result of significant fibrosis, which was repaired, but in the immediate postoperative period he presented severe liver failure with hemoperitoneum; the patient was reoperated for suspected acute portal thrombosis, which was not confirmed, and died on the third postoperative day. Another patient underwent reoperation for choleperitoneum due to a leak of the hepaticojejunostomy; lavage and drainage were performed, and subsequent patient progress was correct.

Intraoperative Details and Postoperative Morbidity.

| PD (n=22) | DPPHR (n=12) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical time (min), median (range) | 330 (220–450) | 390 (240–480) | .091 |

| Transfusion, n | 4 | 0 | .102 |

| Morbidity, n | 10 | 5 | .832 |

| Pancreatic fistula | 1 | 3 | .077 |

| DGE | 5 | 0 | .074 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 1 | 0 | .028 |

| Surgical site infection | 1 | 1 | .654 |

| Respiratory infection | 1 | 3 | .077 |

| Biliary fistula | 1 | 0 | .453 |

| Hemoperitoneum | 1 | 0 | .453 |

| Clavien ≥IIIb, n | 2 | 0 | .131 |

| Hospital stay (days), median (range) | 15 (8–90) | 11 (7–22) | .209 |

PD: pancreaticoduodenectomy; n: number of cases; DPPHR: duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection; DGE: delayed gastric emptying.

The pathology study found changes consistent with chronic pancreatitis and absence of cancer in all cases. Given the length of the series, the information that has been recorded for the surgical specimens is irregular, and it has not been possible to thoroughly examine the pathology findings.

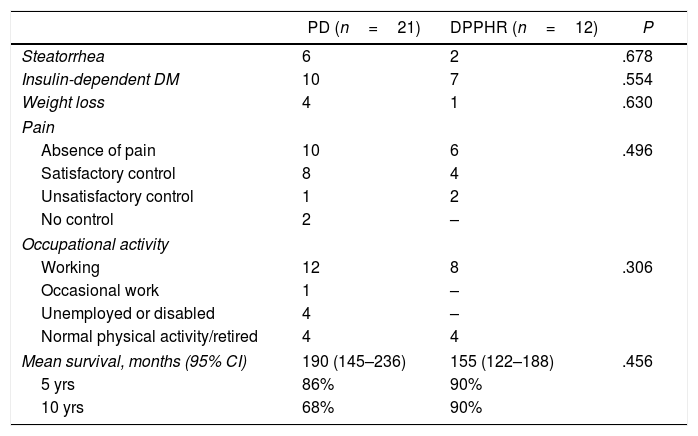

Long-term EvolutionMedian follow-up was 117 months (range 3–301); one patient was lost to follow-up. Table 3 shows the number of cases of the variables evaluated in the long term. Pain was satisfactorily controlled in 85% of the patients, while 5 patients had unsatisfactory control and/or no control of pain after the procedure (2 relapsed in alcohol consumption). The two patients who did not present pain control had episodes of acute pancreatitis during follow-up. There was 43% de novo DM (12/28), all insulin-dependent.

Long-term Follow-up.

| PD (n=21) | DPPHR (n=12) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steatorrhea | 6 | 2 | .678 |

| Insulin-dependent DM | 10 | 7 | .554 |

| Weight loss | 4 | 1 | .630 |

| Pain | |||

| Absence of pain | 10 | 6 | .496 |

| Satisfactory control | 8 | 4 | |

| Unsatisfactory control | 1 | 2 | |

| No control | 2 | – | |

| Occupational activity | |||

| Working | 12 | 8 | .306 |

| Occasional work | 1 | – | |

| Unemployed or disabled | 4 | – | |

| Normal physical activity/retired | 4 | 4 | |

| Mean survival, months (95% CI) | 190 (145–236) | 155 (122–188) | .456 |

| 5 yrs | 86% | 90% | |

| 10 yrs | 68% | 90% | |

DM: diabetes mellitus; n: number of cases.

At the end of the study, 14 patients had died (41%): 7 from de novo neoplasia, 2 from decompensation of their liver cirrhosis, one from upper gastrointestinal bleeding and one during the immediate postoperative period; the cause of death was unknown in 3 patients. These de novo malignancies included lung cancer (2), gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer (2), supraglottic carcinoma, and metastasis of squamous carcinoma with unknown primary tumor. The two patients who presented with pancreatic cancer in the area of the pancreatic remnant were from the PD group, causing death 17 and 19 years after surgery.

DiscussionThe main symptom of chronic pancreatitis is chronic pain, due to the existence of a ductal hyperpressure component, and neuronal damage secondary to the inflammatory component and pancreatic fibrosis.2,13 This symptom is difficult to control and must be addressed by a multidisciplinary team. Proof of this is the constant concern of the scientific community in finding a solution to pain in chronic pancreatitis. Current evidence is based on the publication of several randomized studies,3,4,14–23 meta-analyses24–26 and clinical guidelines from various medical societies worldwide.2,27–30 Among the latter, we must highlight those of the Spanish Pancreatic Club13,31 and, more recently, the United European Gastroenterology (UEG) guidelines from 2017.29

The morphology of the gland and the presence of calcifications or duct dilatation will help select the best surgical technique. At the moment, two randomized studies have shown better results after surgery than after endoscopy in terms of pain improvement16,22 in cases of ductal dilation due to chronic pancreatitis. Thus, patients with ductal dilation will be candidates for pancreaticojejunostomy. However, in cases with the appearance of an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas, bypass surgery will fail and resection should be considered as a central aspect of surgery for the treatment of pain.

Regarding the best surgical technique in the presence of pathology in the head of the pancreas, randomized studies3,4,15,18,21,32–35 and meta-analyses24,36 published since 1995 have compared the results of PD versus duodenum-preserving techniques. Some studies have demonstrated better results among duodenum-preserving techniques in terms of postoperative hospital stay,33,34 overall morbidity18,32,33 or duration of surgery.4,21,33 Similarly, certain meta-analyses indicate lower morbidity in duodenal preservation techniques.26,36 However, other groups demonstrate similar morbidity after the two types of interventions.3,4,15 The morbidity of our series was 44% and hospital mortality 3%, which are results comparable to other publications,4,25,37 with no significant differences between the two groups. In the comparison of the groups, we observed an older age and greater comorbidity among the patients in the DPPHR group. Despite this, severe complications were more frequent among patients who underwent PD, with no statistically significant differences, and we registered a higher rate of intra-abdominal abscesses in the PD group. On the other hand, the morphological lesions of chronic pancreatitis were comparable between groups, except for a greater presence of pseudocysts in the DPPHR group in the preoperative radiology study. Most likely, since the patients in the DPPHR group are more recent, the radiological technique was more detailed and a greater number of pseudocysts were recorded with no other justifying reason.

Regarding pain control, most studies show similar levels of pain control after surgery,18,21,32–34 despite the fact that some authors demonstrate better results in duodenum-preserving techniques.3,4 In our series, we observed pain control in 85% of patients. Regarding endocrine function, only one study advocated better hormonal control after duodenum preservation3; in our series, we registered 43% of de novo diabetes after surgery, with no significant differences between groups. We found an improvement in the control of steatorrhea in patients who underwent duodenal preservation, as reported by other authors.20 Most studies with long-term assessment, including differences in quality of life, do not show differences in this regard between duodenum-preserving techniques and PD.4,15,35,38 Lastly, in the long-term follow-up, we have recorded 5 and 10-year survival rates of 88% and 75%, respectively, which are results similar to other series.39 Specifically, we registered 14 deaths (40%) at the end of the study; 7 were due to de novo malignancies, some of which were secondary to tobacco or alcohol consumption. As is known, patients with chronic pancreatitis are especially susceptible to developing neoplasms secondary to tobacco or alcohol consumption.

Since the surgical indications for resection of the head of the pancreas as treatment for refractory pain in chronic pancreatitis are very strict, it is difficult to obtain a large population of patients in a short period of time. Because of this, we have carried out this retrospective study of our series over a period of more than 20 years. Furthermore, a multicenter study in our setting was difficult to design. During the first years, PD was the surgery preferred by the surgical team, and DPPHR was incorporated in 2002 after the appearance of German series published on the subject, making DPPHR the technique of choice in view of the good results published. One of the limitations of the study would be the comparison of two surgical techniques with dissimilar inclusion periods; however, given the identical data collection process, treatment intention and surgical team, we consider this limitation an acceptable bias. Another limitation of the study is the short preoperative follow-up time of our patients. This is due to the characteristics of our patients, who are referred from other hospitals with the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis after long-term follow-up by other specialists.

In conclusion, surgical resection proves to be a good treatment for intractable pain in patients with an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas. In our study, we were unable to demonstrate a significant difference between the two techniques, although we currently choose to perform DPPHR as the technique of choice. However, we believe that technique selection should depend on the experience of the surgical team.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Lopez Gordo S, Busquets J, Peláez N, Secanella L, Martinez-Carnicero L, Ramos E, et al. Resultados a largo plazo sobre la resección de la cabeza pancreática por pancreatitis crónica: ¿duodenopancreatectomía cefálica o pancreatectomía cefálica con preservación duodenal? Cir Esp. 2020;98:267–273.