A chyle fistula is an uncommon complication following abdominal and pancreatic surgery, particularly in the retroperitoneal compartment. It can also appear as a complication of a severe acute pancreatitis. Medical treatment is the initial approach, but resolution is often slow. Somatostatin or octreotide can help in accelerating the resolution of fistulae.

Patients and methodsPatients developing a chyle fistula (output >100ml/24h, normal amylase levels and triglyceride concentrations above 110mg/dl) associated with pancreatic disorders were treated with oral intake restriction and parenteral nutrition, followed by subcutaneous octreotide 0.1mg/8h.

ResultsFour female patients aged 55–80 years, who underwent pancreatic surgery or presented with an acute pancreatitis, were treated. Chyle fistulae ranging from 100 to 2000ml/24h were treated with octreotide, being resolved within five to seven days. No recurrence has been found in a 2–4 years follow up.

ConclusionsWe have found that chyle fistula medical treatment is often related to a slow resolution, somatostatin or octreotide administration dramatically reduces its duration. Other previously reported studies have also shown that the quick onset of such treatment can accelerate the whole process, leading to a shorter recovery and lower hospital costs.

La fístula quilosa es poco frecuente en el postoperatorio de diferentes tipos de intervenciones abdominales, especialmente del espacio retroperitoneal, como las pancreáticas. Puede desarrollarse también en el curso de una pancreatitis aguda grave. El tratamiento inicialmente es conservador y puede dilatarse en el tiempo, aunque puede abreviarse con el uso de somatostatina u octreótido.

Pacientes y métodosLos pacientes afectos de enfermedad pancreática que presentaron una fístula quilosa durante su ingreso (débito mayor de 100cc/24h, niveles de amilasa pancreática normales y triglicéridos superiores a 110mg/dl) fueron tratados inicialmente con dieta absoluta y nutrición parenteral total, seguido de la administración de octreótido 0,1mg/8h por vía subcutánea.

ResultadosCuatro pacientes mujeres de entre 55 y 80 años, presentando cirugía pancreática o pancreatitis aguda, desarrollaron una fístula quilosa con débitos entre 100 y 2.000ml cada 24h. Tras la administración de octreótido, las fístulas se solucionaron entre el quinto y el séptimo día de tratamiento, sin presentar recidiva durante un seguimiento de 2 a 4 años.

ConclusionesDado que el tratamiento médico de la fístula quilosa en general se asocia a un curso lento, y que la administración de somatostatina u octreótido produce una drástica resolución del cuadro, tal como hemos constatado en nuestra observación y como aparece descrito por otros autores, el inicio precoz de este tratamiento puede acelerar su curación, lo que redunda en un acortamiento de la recuperación del paciente y en una disminución del gasto hospitalario.

A chylous fistula is a complication that can appear during the course of several abdominal diseases, such as tumors and infections, and may also be due to the effects of radiation or abdominal, thoracic or cervical surgery.1–3 It is defined as lymph leakage, which is a material that is milky in appearance, sterile, denser than peritoneal liquid with a high triglyceride content (TG) (>110mg/dl to 200mg/dl), after initiating oral intake.1,4 Lymph contains lymphocytes and immunoglobulin, and its extravasation can lead to important morbidity and consequently higher hospital costs. This entity is rare and is found in the postoperative period of different types of abdominal operations, especially those in the retroperitoneal space (approximately 1:20000 of complex retroperitoneal procedures),1,5 thoracic surgery and cervical dissections. Lymphatic fistulas are caused by damage to lymph structures.3,4,6,7 In abdominal surgery, this is probably due to trauma to the terminal dilation of the thoracic duct or one of its major lymphatic tributaries. The majority of cases are secondary to aortic or renal interventions, while other interventions such as pancreatic surgery have been less frequently reported.1,4,7 Likewise, chylous fistula can develop in the course of acute pancreatitis caused by injury to the peripancreatic lymph nodes.8–10

Treatment is initially conservative, with withdrawal of oral intake and the start of total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Frequently, however, the resolution of chylous fistula is lengthy and, occasionally, when it fails to resolve a surgical approach is indicated (ligature or peritoneovenous shunt),4,11 which increases the morbidity and mortality of these patients. There are reports that both somatostatin and octreotide can shorten the healing period in patients with chylous fistula2,6,12,13 and are an effective tool in this clinical situation.

Patients and MethodsWe have compiled the data of patients affected by pancreatic disease who presented chylous fistula during hospitalization. The criteria used to define chylous fistula were the appearance of a milky exudate through the abdominal drains, with an accumulation of more than 100cc/24h, normal pancreatic amylase levels and TG higher than 110mg/dl. All patients were initially treated with TPN and no oral intake, followed by the subcutaneous administration of octreotide (0.1mg/8h) (Sandostatin®, Novartis Pharmaceuticals). Fistula output was expressed in ml for every 24h and the healing time was registered in days.

ResultsBetween January 2008 and June 2010, 4 patients developed chylous fistula related with pancreatic surgery or during acute pancreatitis, all of whom were successfully treated with octreotide.

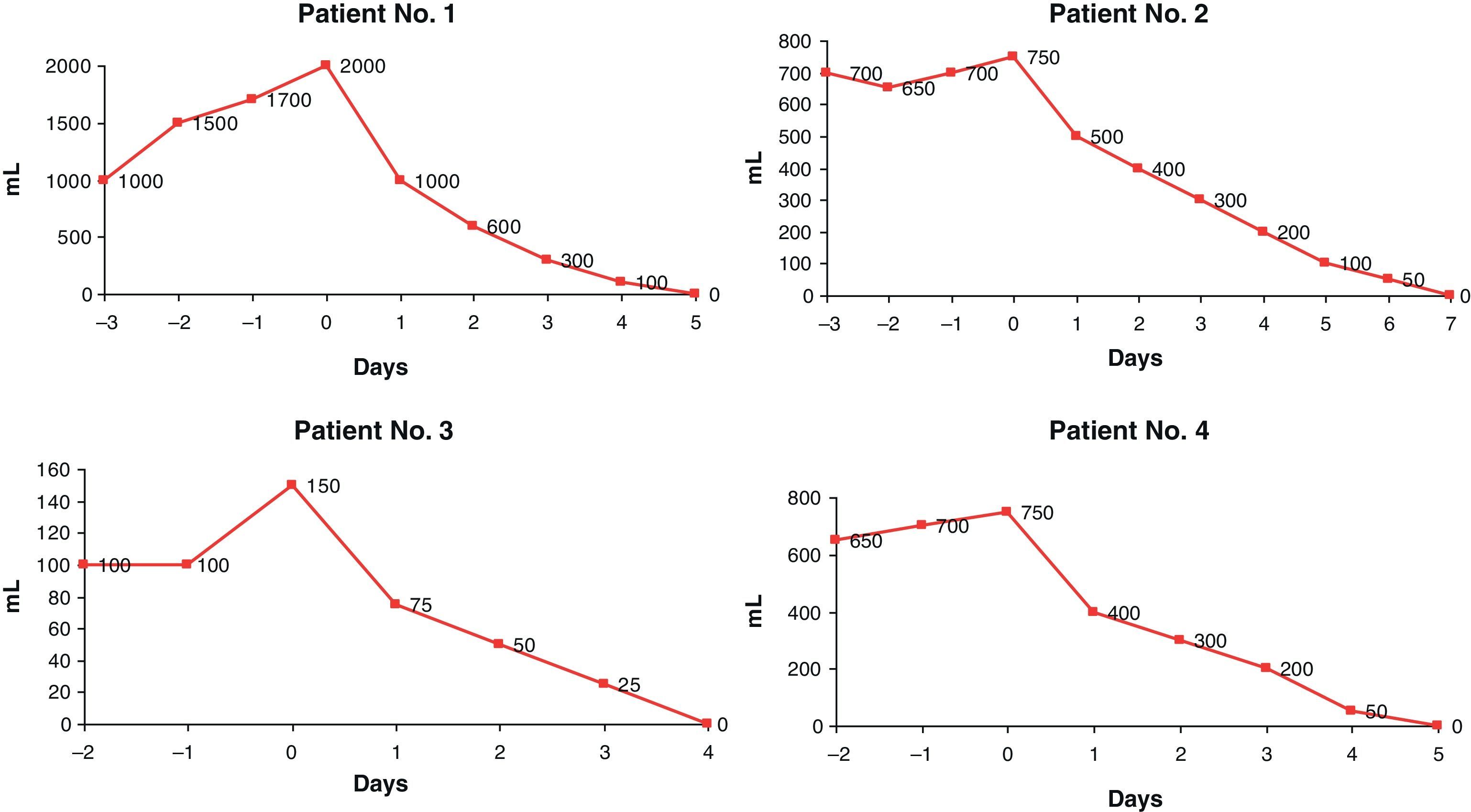

Case 1An 80-year-old woman with no relevant medical history presented with neoplasia of the head of the pancreas. The patient underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy with pyloric preservation (stage pT3N0Mx). The postoperative course was favorable, with abundant sterile peritoneal exudate that was serous in appearance and normal amylase levels. The exudate later became milky in appearance with a discharge of more than 2000ml in 24h and high TG levels (150mg/dl) when oral intake was initiated on the 7th day after surgery. When oral intake was withdrawn and parenteral nutrition was maintained, there was no decrease in the fluid discharge in spite of the fasting and parenteral nutrition. On the 10th day post-op, octreotide was administered (0.1mg/8h), resulting in a drastic reduction of the output, which was practically resolved 5 days later. Oral intake was then reintroduced, with no observed chylous exudate (Fig. 1). The patient was moved to the convalescence unit 20 days after surgery. The patient died due to the progression of her disease 14 months later, with no signs of relapse of the lymphatic leak.

Case 2The patient was a 55-year-old woman with a history of alcoholism and morbid obesity, who had been treated some weeks before for acute pancreatitis. She presented a Balthazar grade E pancreatitis with peripancreatic necrosis that evolved into a pancreatic abscess (E. coli), which was drained percutaneously. The patient required mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure. She was readmitted due to a distended abdomen, pain and poor general health, requiring admittance to the intensive care unit due to new organ failure. A CT scan revealed a liquid collection that was suggestive of ascites. This was drained percutaneously (S. pneumoniae), obtaining a milky liquid with normal amylase and a high TG content (200mg/dl), with an initial drainage of 700ml/24h. The patient received treatment with cefotaxime in accordance with the antibiogram. Parenteral nutrition was initiated, without any observed reduction in the discharge amount during the first 3 days until octreotide was introduced at 0.1mg/8h, which lead to total resolution on the 7 days later. This meant that the drain was able to be withdrawn and oral uptake reinitiated without any evidence of relapse. The patient did require, however, a new percutaneous drain for a residual collection, with no appearance of chyle, until the patient was discharged 20 days after admittance. She has had no new episodes of pancreatitis or ascites in the last 4 years (Fig. 1B).

Case 3Due to dyspepsia, a 75-year-old woman was diagnosed by ultrasound and MR cholangiography with bile duct dilation without analytical cholestasis or cholelithiasis. Endoscopic ultrasound was attempted for study of the ampulla and a stenosis of the second duodenal portion was detected, with no evidence of malignancy on the biopsies of the duodenal mucosa. During endoscopic pneumatic dilation, a duodenal perforation occurred, and the patient underwent surgery with mobilization of the duodenum and pancreas, biopsies (negative for tumor) and duodenal–jejunal Roux-en-Y derivation. The patient was maintained with parenteral nutrition and, when oral intake was reinstated on the 7th day after surgery, within 24h the drains collected 100ml of milky liquid that was rich in TG (225mg/dl). This was resolved 96h after the administration of octreotide at 0.1mg/8h (Fig. 1C). After being discharged 2 weeks later, the patient continues to be asymptomatic 3 years later.

Case 4A 78-year-old woman, with a history of acute pancreatitis 3 months before hospitalization, presented with a suspected ductal disruption on MRI images that had been ordered for the study of pseudocysts in the pancreatic head and tail, the latter of which presented infection (E. cloacae and K. pneumoniae). For this reason, percutaneous drains were inserted and treatment was initiated with cefuroxime in accordance with the antibiogram. After a Roux-en-Y double derivation of the pancreatic pseudocysts, the patient presented during the postoperative period serous drainage of up to 750ml in 24h, which became chylous in appearance with a TG of 134mg/dl when oral intake was reinstated on the 5th postoperative day. The patient had been treated from the start with parenteral nutrition, and octreotide at 0.1mg/8h was added, which resolved the chylous fistula by the 5th day (Fig. 1D). The patient was discharged 2 weeks after surgery. She has presented no relapse in the follow-up studies over the course of the 2 years of follow-up.

DiscussionSeveral abdominal diseases and interventions, especially those performed in the retroperitoneal compartment such as the pancreatic region, may cause injury to the regional lymphatic vessels with the appearance of ascites or chylous fistula. Although uncommon, chylous ascites can appear as a complication of acute pancreatitis of various etiologies. On its own, it does not seem to negatively influence the prognosis of pancreatitis, and treatment does not differ from that of other causes.8–10

The publication of cases related to pancreatic surgery is very limited compared with other interventions, and only 5 cases were published before 2007.14–18 Consequently, the actual incidence is difficult to estimate. In the series of more than 3500 pancreatectomies published by Assumpcao et al.,1 the incidence was 1.3% and 1.8% in cephalic pancreatoduodenectomies. Likewise, in a cohort at Kings College4 of 138 patients who underwent pancreatic resection, an incidence of 1.4% was observed. Contrarily, the series by the Glasgow Royal Infirmary19 reports an incidence of 6.7% and, more recently, Van der Gaag7 published an incidence of 9% after pancreatoduodenectomy. This demonstrates the disparity in the criteria used, as the authors have commented. The most extensive Spanish series on the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma by means of cephalic pancreatoduodenectomy20,21 gives no details about the appearance of this complication. The extensive dissection of the retroperitoneum, the number of lymph nodes resected, venous resection, surgical time and the early reinstatement of enteral nutrition are the most important risk factors for the appearance of chylous fistula, more so than the characteristics of the patients themselves.1,4,18,22

The prevention of lymph node injury is complex because these vessels are not visible when fasting. Nevertheless, the instillation of a lipid solution in the jejunum some minutes before the intervention19 makes them visible for their ligation or sealing. The treatment of chylous fistulas involves different conservative measures, the failure of which leads to interventional solutions that go from lymphography and embolization11,23 to surgical lymphostasis,11,24 with results that are not always optimal. Conservative treatment begins with guaranteeing proper drainage of the fistula, or repeated paracentesis in the case of chylous ascites, in order to prevent compression symptoms, facilitate the evacuation of potentially infected fluids and control the volume and characteristics of the exudate. Feeding with medium-chain TG that is absorbed directly via the portal vein25 contributes to preventing the loss of TG through the fistula.

TPN is another important pillar in the treatment as it provides necessary nutritional support, reduces the discharge through the fistula by allowing the intestine to rest and impedes the presence of TG in the drained lymph as they are not absorbed. Conservative treatment with TPN (which can lead to a decrease in lymphatic flow from 220cc/kg/h to 1cc/kg/h)5,11,26 results in an approximate cure rate of 60%–100% of chylous fistulas in several regions, with a cure time of between 2 and 6 weeks,2,25,27 even though a series reached resolution in less than 7 days.7 When somatostatin or octreotide is administered together with TPN to treat lymphatic fistulas in different situations, resolution is reached in less than 7 days in most cases.2,6,12,24,26–29 When comparing conservative or local chemical treatment with somatostatin or octreotide in lymphorrhea secondary to axillary dissection or renal transplantation, both leak volume and cure time were significantly less.27,30 As there are no observed differences between the use of somatostatin or octreotide in gastrointestinal or pancreatic fistulas,31 their use in chylous fistulas are presumed to be equivalent, although the administration type and cost of octreotide are more advantageous.

The mechanisms of action have not been clearly determined. Somatostatin and octreotide reduce the intestinal absorption of fat and the concentration of TG in the thoracic duct, while also decreasing the flow22 in the main lymph ducts where there are somatostatin receptors.29,32 Furthermore, they reduce gastric, pancreatic and intestinal secretion, inhibit the motor activity of the intestine and diminish the process of intestinal absorption and splanchnic blood flow. All this may contribute to the closure of the lymph fistulas.2,6,7,12,22 Nonetheless, the prophylactic use of somatostatin in pancreatic surgery did not prevent the appearance of chylous fistula in the Van der Gaag series.7

Regardless of whether the chylous leak arises in the context of pancreatic surgery or pancreatitis, in our experience the introduction of octreotide at a dosage of 0.1mg every 8h resulted in an important reduction of the output through the drain tubes over a period of 4–7 days without any adverse effects being detected, and oral intake can thus be reintroduced. In the patient with pancreatitis and chylous ascites, the volume did not start to diminish until octreotide was initiated, despite having interrupted oral intake 3 days before. In the postoperative patients in whom no evidence of pancreatic fistula was observed, the output of the drains varied ostensibly, although cases 1 and 4 presented a large volume that probably reflected the lymph leak that was suspected and confirmed when oral intake was initiated due to the chylous appearance. Given that all of them interrupted oral intake and had begun support with parenteral nutrition, it can be inferred that the cure rate after the administration of octreotide is attributable to this medication. The surprising speed of resolution has been documented by other authors in different contexts.2,3,6,12,13,22,25,27,28,33,34 The clinical relevance of the fistulas that we have treated is evidently difficult to compare with regard to the volume, although none of them had any impact on the condition of the patient due to their quick resolution. Nevertheless, it may be useful to adopt a classification such as that proposed by the Van der Gaag group,7 who take into consideration the volume, duration, general state, intervention, hospital stay and readmittance, according to which all our cases would be classified as mild. This raises the question of whether the administration of octreotide would be justified even in mild cases with low output, which contrasts with the position of Huang12 who argues that treatment should be initiated as soon as the chylous fistula is documented, as was done in case 3. In oncological surgery of the head of the pancreas, there is only one reference in the literature about the influence of chylous leak on survival.1 While in patients with well-drained fistula the 3-year survival was 53%, among patients who presented chylous ascites (who had a slower resolution) it reached 18%, with no specified difference in oncologic stage. Faster resolution of the chylous leak could lead to better survival, as long as it is not an epiphenomenon of another cause for this poorer evolution.

Conservative treatment of chylous fistula is generally associated with a slow course and the administration of somatostatin or its analog octreotide causes a drastic resolution of the symptoms, as we have observed and has also been described by other authors.2,3,6,12,13,22,25–28,33,34 We believe that early initiation of this treatment can accelerate healing, which results in faster patient recovery and lower hospital costs.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare having no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Zárate Moreno FA, Oms Bernad LM, Mato Ruiz R, Balaguer del Ojo C, Sala Pedrós J, Campillo Alonso F. Eficacia del octreótido en el tratamiento de la fístula quilosa asociada a enfermedades pancreáticas. Cir Esp. 2013;91:237–242.

The content of this article was presented at the International Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association Congress in Buenos Aires in April 2010 and at the XX Jornades de Cirurgia als Hospitals de Catalunya in Vic, Spain on October 7 and 8, 2010.