Given the raising environmental concerns over lead toxicity, replacing the common lead-based piezoelectric ceramics with a proper alternative became a hot topic. (Na0.5K0.5)NbO3 (KNN) is considered a potential replacement for such ceramics. This work presents the synthesis of KNN-type ceramics based on conventional solid-state reaction, where the effect of precursor particle size is studied. A combined mechanical activation by ball milling and calcination at low temperature of 800°C is applied. The phase structure evolution, morphology and mechanical properties are investigated systematically with the particle size and the calcination rate. The results indicate a marked effect of the precursor particle size on the properties of obtained ceramics. Secondary phase content could be lowered and tetragonality improved by the applied approach. Despite the presence of secondary phases, dielectric measurements indicated typical values of dielectric constant and loss for piezoelectric materials.

La sustitución de las cerámicas piezoeléctricas comunes a base de plomo por una alternativa adecuada, se convirtió en un tema importante debido a las crecientes preocupaciones medioambientales por la toxicidad del plomo. Los (Na0.5K0.5)NbO3 (KNN) se consideran un posible reemplazo para cerámicas piezoeléctricas comunes a base de plomo. Este trabajo presenta la obtención de cerámicas tipo KNN mediante una reacción convencional en estado sólido donde se estudia el efecto del tamaño de las partículas precursoras. El método de síntesis ha empleado una combinación de molienda de atrición para activar la mezcla de precursores y de calcinación a baja temperatura de 800°C. La evolución de las fases, la morfología y las propiedades mecánicas se investigan sistemáticamente con el tamaño de partícula y la rampa de calcinación. Los resultados indican un marcado efecto del tamaño de partícula del precursor sobre las propiedades de las cerámicas obtenidas. El contenido de fases secundarias y de la fase tetragonal se pueden ajustar ligeramente mediante el método presentado. Las medidas dieléctricas han indicado valores típicos para las cerámicas piezoeléctricas (constante dieléctrica y pérdidas) a pesar de la presencia de fases secundarias.

The lead zirconate titanate (PZT) ceramics have been dominating the global piezoelectric ceramics market for the past decades [1]. However, the serious health issues caused by the lead content required the fabrication of piezoelectric ceramic to align with the RoHS directive on reducing the use of hazardous substances and thus, to find harmless replacements [1,2]. In this respect, the (K,Na)NbO3 (KNN) ceramics received increased interest for a variety of applications also based on their high Curie point, low density and good electromechanical properties [3]. The composition is known to control the piezoelectricity properties due to polymorphic phase transition (PPT) between tetragonal (T) and orthorhombic (O) phase [4]. PPT is not only compositional but also temperature dependent, leading to piezoelectricity degradation at high temperature. An improvement in piezoelectric properties is mainly determined by their crystallographic anisotropy nature. A marked enhancement of longitudinal piezoelectric coefficient d33 in KNN ceramic structures was reported when rhombohedral and orthorhombic phases are dominant but show crystallographic anisotropy [5].

While the oxide solid-state reaction is considered the most cost-effective method employed for the synthesis of KNN-based piezoceramics [6], several problems occur such as the formation of extra phases induced by any slight stoichiometric change [7] and the need for a calcination step due to the hygroscopic nature of the alkali carbonate precursors [8]. On the other hand, the high volatility of the alkali elements at high temperatures, and the narrow sintering temperature range (melting takes place at 1140°C) make it difficult to obtain dense, well sintered KNN ceramics by common solid-state reaction method [9]. The common solid-state synthesis procedure is based on the ball milling of the mixture of starting materials for 4–8h and calcination between 750 and 900°C for 2–6h [10]. Alternatives include a regrinding step of calcined mixture and/or double calcination [11]. Under these circumstances, one of the approaches to improve the KNN synthesis is to apply low temperature solid-state synthesis. Such temperature needs to be high enough to ensure the synthesis of homogeneous high-purity KNN but low enough to avoid the formation of agglomerates [12].

A mechanochemical activation-based (MA) approach [13] has been proposed based on the mechanical treatment by ball milling of the reactant mix to provide with proximity of the reactants and initiation of the synthesis reaction. Such approach could provide with proper synthesis conditions given the fine size of the grains of the precursors which increase the mixture reactivity and thus, it lowers the synthesis temperature [14]. The mechanochemical activated synthesis was also shown to tailor the dielectric permittivity by the grain size changes in the ceramics [15,16]. The calcination temperature for the mechanochemical activated powders was lowered to 550°C but their milling duration was a large as 25–100h [14]. Therefore, such approaches are time and energy consuming.

The aim of this work was to explore the combined effect of the precursor particle size and the calcination rate on the formation reaction of KNN and the properties of obtained ceramics including microstructure, crystal structure and dielectric permittivity. While there are many works on KNN synthesized by solid-state reaction, here a simple approach is proposed to easily control the particle size of the precursors by ball-milling step, to activate the homogenized precursors mechanically with a ball-milling step as short as 2h and study the combined effects with single calcination step at 800°C for 2h under varying heating rates. The easiness in control of downsizing and activation resides from varying the ball-to-powder ratio. The obtained results indicate a successful modification of particle size and together with adjusting calcination conditions, one could lower the content of secondary phase and improve the tetragonality in the obtained ceramics. Dielectric properties were found to be in line with typical piezoelectric materials.

Experimental methodsMaterialsCommercial niobium (V) oxide (Nb2O5, 325 mesh, <44μm), K2CO3 and Na2CO3 (anhydrous) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (UK) Co., Ltd.

Synthesis of KNN ceramicsThe precursors were homogeneized inidividually by ethanol wet milling in a planetary ball mill Fritsch Pulverisette 7 at 400rpm for 8 cycles of 10min on time and 5min idle time. The ball material employed in the attrition milling was Y2O3 stabilized ZrO2 of 1mm diameter. The milling energy was varied by employing a ball-to-powder ratio (RBP) of 5:1 or 10:1. The homogenized powders were dried at 100°C for 24h and further mixed according to the stoichiometric formula, namely in the mass fractions 68.5247%, 13.6604% and 17.8150% for Nb2O5, Na2CO3, and K2CO3. The lead-free systems were prepared by the conventional solid-state reaction method reaction in three steps namely, mechanical activation, calcination and sintering. First, the KNN mixtures were mechanically activated (MA) by employing the same conditions of ball milling as for the individual precursors, namely by employing a ball-to-powder ratio (RBP) of 5:1 or 10:1. After the mechanical activation, the powder mixtures were dried at 100°C for 24h, sieved and subjected to calcination in air by using a Carbolyte HTF1800 furnace. The calcination was performed at 800°C with a calcination ramp (CR) of 3°Cmin−1 or 10°Cmin−1 and 2h dwelling. The calcined powders were then sieved again and compacted with a cold isostatic press (KSC15A) under 20MPa pressure for 2min. The sintering was further performed by temperature increase up to 1100°C with a heat rate of 10°Cmin−1 and 2h dwelling followed by furnace-cooling to room temperature overnight.

Characterization of KNN ceramicsThe particle size of the precursors and mixtures was obtained by light scattering in water as dispersing liquid with a Mastersizer Hydro 2000, Malvern Instruments analyzer. The volumetric particle size distribution was averaged from three measurements of 12s each at 2000rpm pumping.

The mass changes upon heating and the temperatures where they take place were observed on both precursors and mixtures with a thermogravimetric analyzer TGA Q50, TA Instruments in air atmosphere to simulate the calcination environment. The heat rate employed was 10°Cmin−1.

The fracture surface of the sintered samples have been studied using a field emission gun scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, GEMINI ULTRA 55 MODEL, ZEISS). Elemental analysis was performed on the same microscope equiped with an energy dispersive spectroscopy analyzer.

An X-ray diffractometer (D2 Phaser, Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used to determine the room temperature phase structure. A Bruker D2 phaser diffractometer using a radiation of Cu-kα with a wavelength λ=1.54Å was employed. The fraction of secondary phases was determined by the method of integrate area intensity ratio. Full-spectrum Rietveld refinement considering the ICSD 409464, ICSD 186332 and ICSD 186342 was performed to calculate the fractions of orthorhombic and tetragonal phase.

The bulk density of the sintered samples was measured by Archimedes’ principle by employing distilled water as immersing liquid. At least five measurements were averaged for each sample. The relative density was calculated by dividing the bulk density with the theoretical density of the powder mixture.

Vickers microhardness assessments were carried out by indentation with a microhardness tester (HMV-2 Shimadzu) employing a conventional diamond pyramid indenter and a 0.1kg load for 10s. The samples were previously polished (Struers, model Roto-Pol-31). The diagonals of each indentation were measured using an optical microscope. The value of HV is the relationship between applied load and the surface area of the diagonals of indentation. At least five measurements were obtained per sample.

Relative dielectric permittivity and dielectric losses were measured in a wide range as 10–106Hz, as well as in the range 1–5MHz by using the N4L instrument with the PSM 1735 NumetriQ phase-sensitive multimeter and the impedance analysis interface. The samples were coated with silver paint prior to these measurements.

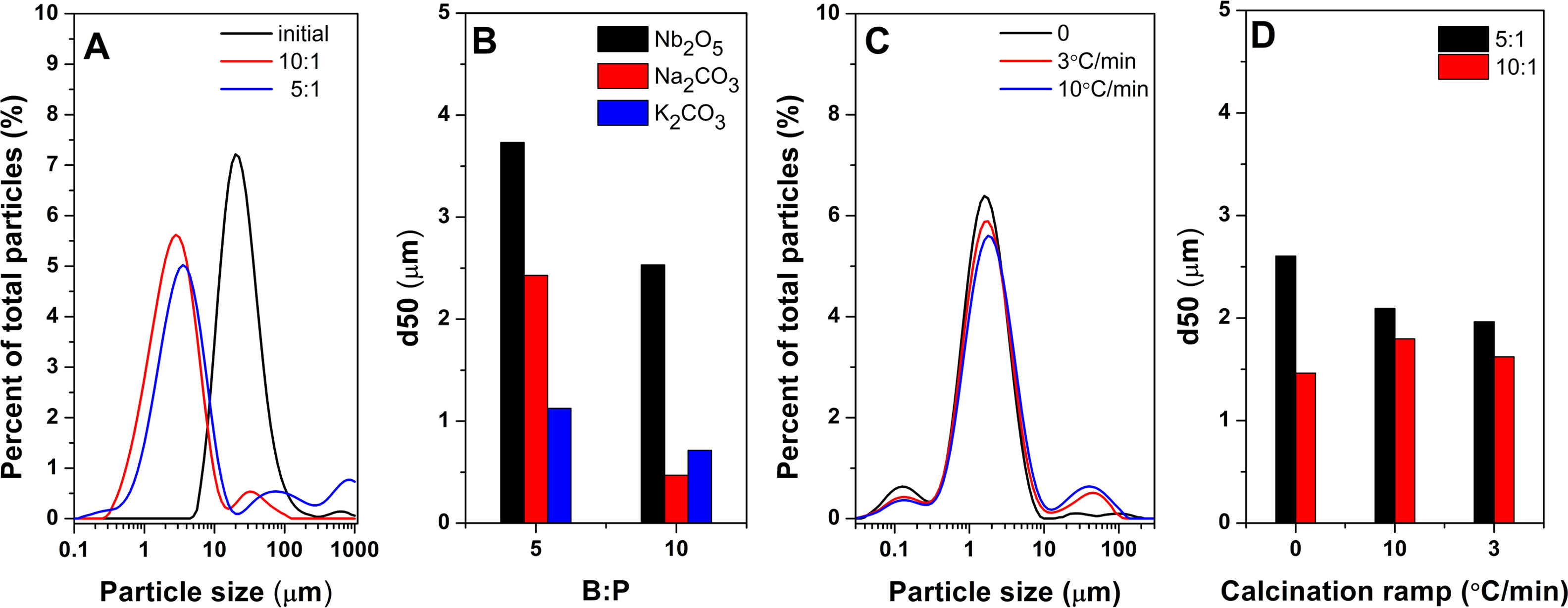

Results and discussionThe course of the solid-state reaction between different downsized precursors was analyzed with the ball-milling conditions employed to homogenize the precursor powders. Given the difference in precursor type, the effect of RBP was observed on the precursors individually and further on the KNN mixtures. Thus, as it is shown in Fig. 1a for Nb2O5, by increasing the BP ratio to 10:1, a downsizing of the precursor particles was obtained. Fig. 2b shows the average particle size for downsized precursors for each BP milling ratio. It can be observed that the increase the BP ratio from 5:1 to 10:1 reduced the average particle size with about 30% for Nb2O5 and K2CO3 while Na2CO3 was reduced 75%, which could be explained by the hygroscopic nature of Na2CO3.

Differential size distribution for Nb2O5 (A), average particle size of mixed precursors as a function of RBP (B), differential size distribution of the mixture activated with RBP 10 with the calcination ramps (C), evolution of average particle size of the mixtures before and after calcinations as function of RBP (D).

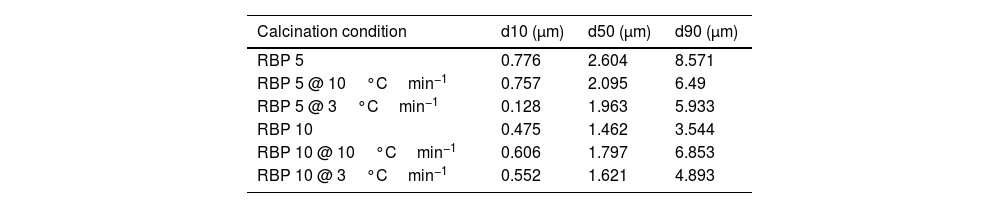

To improve the solid-state reaction, a mechanical activation was performed by ball milling on the downsized precursor mixture. The solid-state reaction of the KNN precursors is affected not only by the particle size of the reactants by also by the calcination rate and dwelling. In this respect, Fig. 1c shows the particle size distribution for the BP 10 downsized mixture before and after calcination with different rates. It is observed that size peaks and corresponding percentages are affected by calcination rate. Fig. 1d compares both the effects of calcination rates and the BP ratio on the average particle size of the calcined mixtures. One can observe that the reaction kinetics depends on the initial particle size of mixture: when smaller precursor particles (d50=1.5μm, red color in Fig. 1d) are subjected to solid-state reaction by calcination, a coalescence process takes place and leads to increased particle size, opposite to the case of larger particles (black color in Fig. 1d) of almost double d50, that appear to still be in decomposition stage, as the d50 decreases. Nevertheless, by employing a slower calcination rate as 3°Cmin−1 vs. 10°Cmin−1, the average particle size decreased, which could be attributed to an evaporation of the material at such rate. Table 1 presents the effect of ball milling and calcination rate on the particle size distribution confirms similar evolution for the 10% and 90% of the powder.

Effect of calcination rate and ball milling conditions on the particle size.

| Calcination condition | d10 (μm) | d50 (μm) | d90 (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBP 5 | 0.776 | 2.604 | 8.571 |

| RBP 5 @ 10°Cmin−1 | 0.757 | 2.095 | 6.49 |

| RBP 5 @ 3°Cmin−1 | 0.128 | 1.963 | 5.933 |

| RBP 10 | 0.475 | 1.462 | 3.544 |

| RBP 10 @ 10°Cmin−1 | 0.606 | 1.797 | 6.853 |

| RBP 10 @ 3°Cmin−1 | 0.552 | 1.621 | 4.893 |

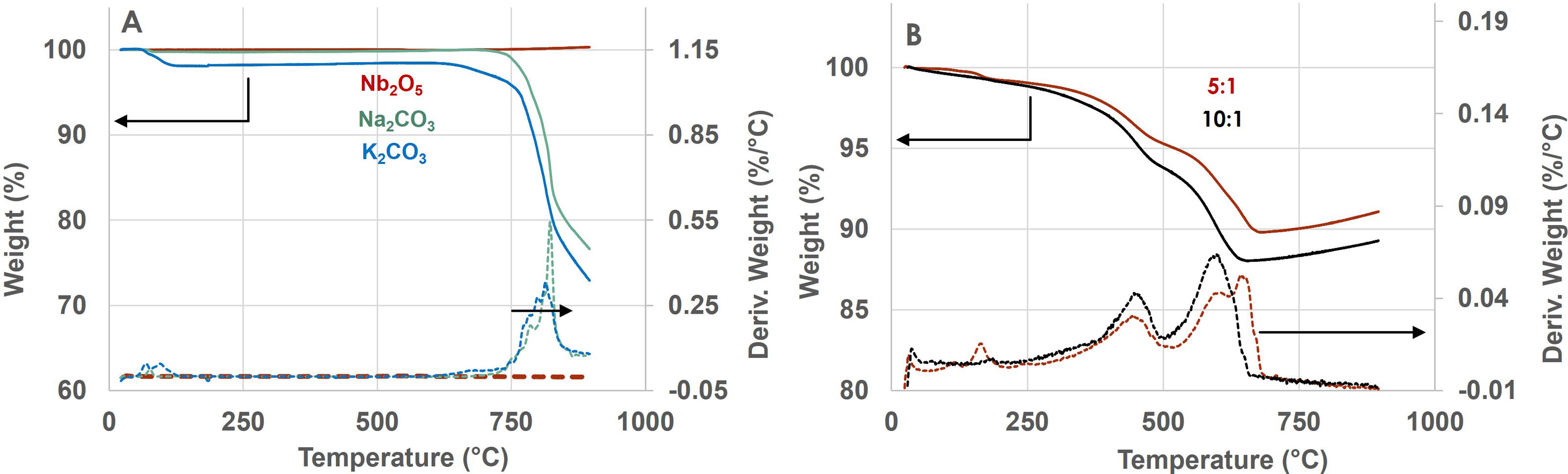

The solid-state reaction formation of KNN was investigated by TG analysis in air with a heating rate of 10°Cmin−1. The weight changes of the original precursors are depicted in Fig. 2a. It is shown that Nb2O5 is stable over the whole temperature range while Na2CO3 and K2CO3 experience dehydration below 100°C and decomposition starting 625°C. Na2CO3 appears to decompose around 820°C and K2CO3 around 830°C, close to their melting points [17].

The mechanically activated mixtures obtained by ball milling of the downsized precursors exhibit a varying mass change as a function of the BP ratio employed in the ball-milling steps, as shown in Fig. 2b. Up to 200°C, the powders may exhibit a weight change which is attributed to dehydration of carbonates. Above 200°C, the DTG peaks are assigned to different stages of the reaction between the alkali carbonates and the Nb2O5[18], namely a first stage located at 459°C ascribed both to the formation of an intermediate layer of (K,Na)2Nb4O11 at the Nb2O5 surface upon decomposition of the carbonates and to the initiation of the formation of stoichiometric (K0.50Na0.50)NbO3 at the surface of the intermediate phase [18]. The first stage occurs at similar temperature, irrespective of the milling conditions, however its value of 459°C is lower than other similar reports (i.e. 511°C) and it is attributed to the double-milling procedure resulting in smaller particle size and activated mixture. Moreover, a higher weight change for the first stage was recorded for the smaller mixture particles (d50 of 1.46μm) induced by RBP 10:1, suggesting more efficiency in initiating the KNN formation with respect to RBP 5:1.

The second reaction stage is indicated by a second peak in the differential thermograms. This stage appears at 608°C which close to other reports (594°C) and is it assigned to the completion of the formation of KNN and diffusion of alkali elements towards the unreacted Nb2O5[18]. The mixture activated with BP 10:1 exhibits a higher weight change in this stage which is attributed to the reactivity of smaller particles.

By comparing the weight loss over the range 200–650°C, the mixture obtained by RBP 10:1 reached a higher value of 11.05% which is closer to the theoretical weight loss for the KNN precursors, i.e. 11.34% [18]. In the higher temperature range, it is observed that the mixtures with RBP 10:1 start incorporating oxygen species at lower temperature (671°C vs. 689°C) than the one activated with RBP 5:1.

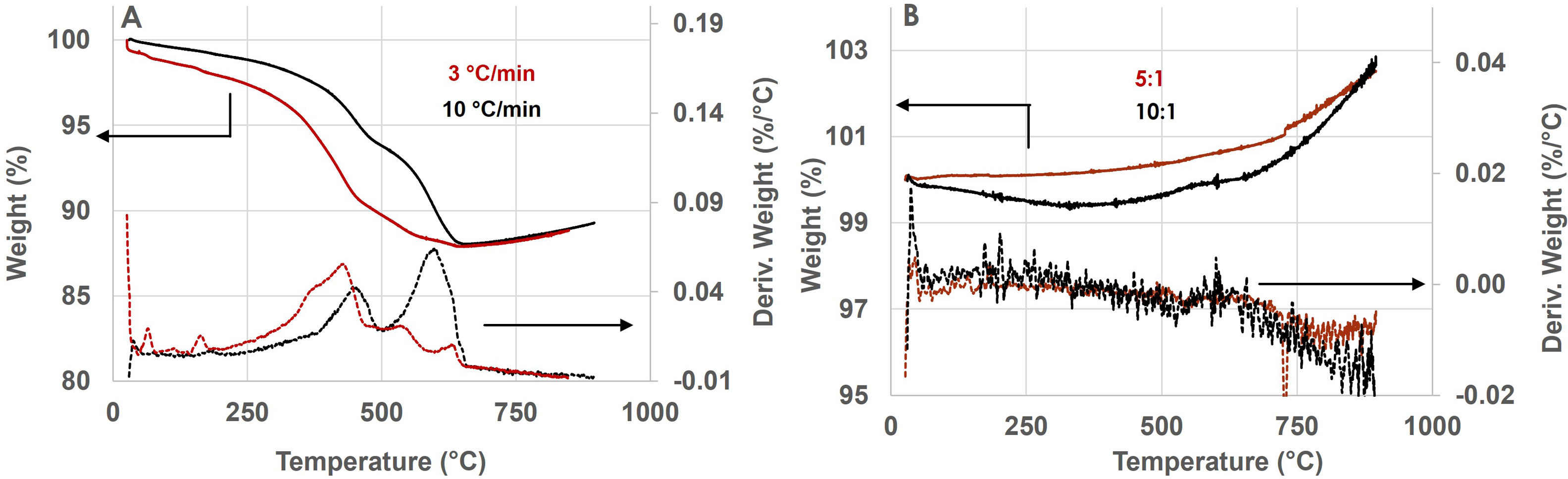

The reactions for the formation of KNN are diffusion-controlled, thus, to analyze the effect of calcination rate, the TG was recorded with lower heating rate as 3°Cmin−1, as well. Comparative thermograms obtained at different heating rates on the mixture with smaller particles activated with BP 10:1 are shown in Fig. 3a. It is observed that the mixture heated with lower rate as 3°Cmin−1 shows the first decomposition stage much earlier, as evidenced by the higher broad peak in the range 335–420°C (vs. 440°C corresponding to the mixture heated with 10°Cmin−1) and 3°Cmin−1 lower peaks in the higher temperature range (554°C and 638°C vs. 1 marked broad peak centered at 609°C) which could be attributed to faster finalizing formation and diffusion of alkali elements due to more contact points provided by smaller particle size.

The calcined mechanically activated mixtures are further compacted and sintered. To monitor the thermal stability and incorporation of oxygen in the calcined mixtures, the mixtures obtained by varying RBP and calcined with varying rates were subjected to TG analysis in air with a heating rate of 10°Cmin−1. Given the marked effect of the lower calcination rate, the comparative thermograms obtained for the activated mixtures upon calcination with 3°Cmin−1 are shown in Fig. 3b. It can be observed that the temperature range can be divided into two sections: the low range corresponding to decomposition/stability and a higher range corresponding to oxygen incorporation. In the lower temperature range, the mixture activated with BP 5:1 is thermally stable, while the one activated by higher BP 10:1 still exhibits a mass change which is indicative for the reactivity of its smaller particles.

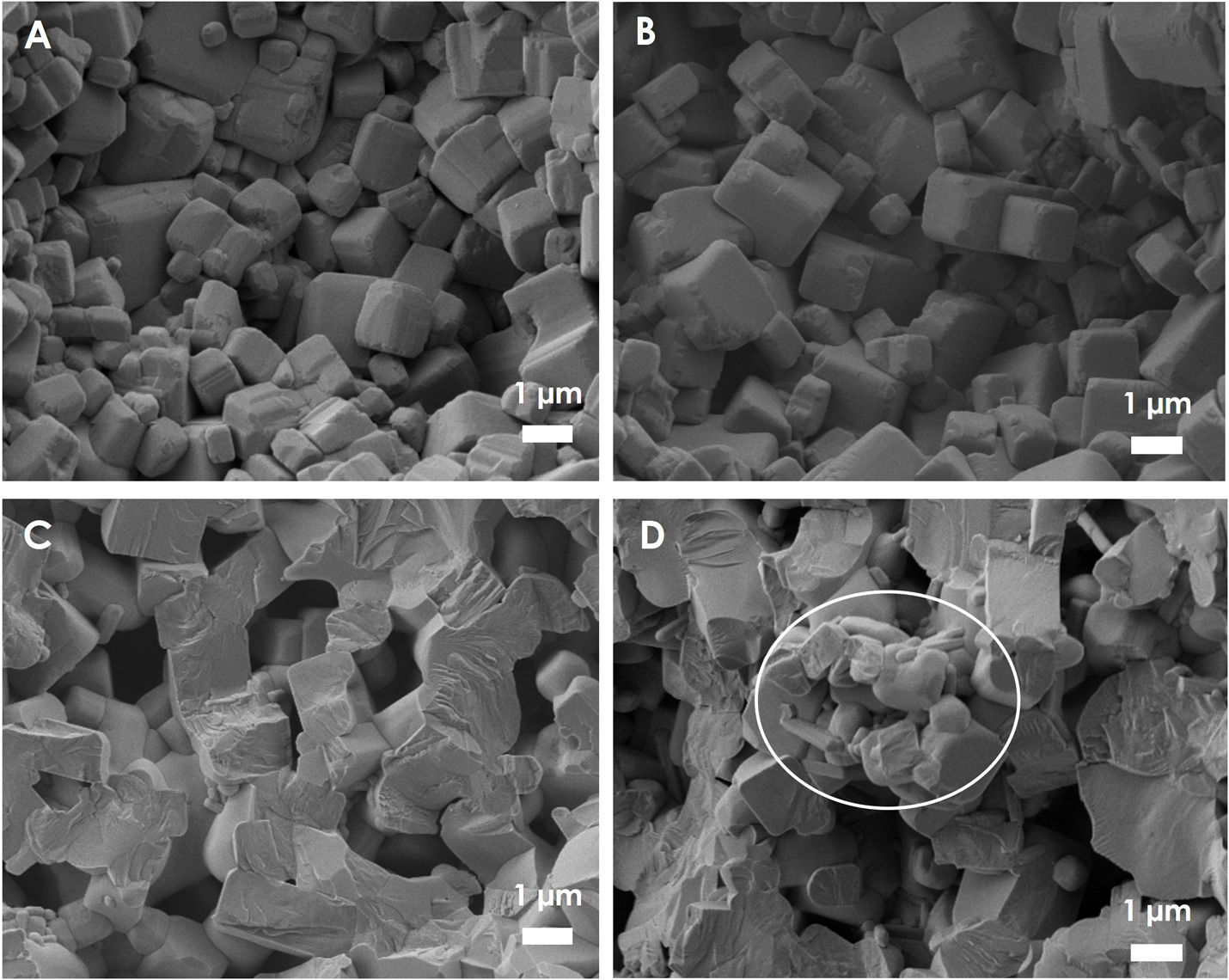

Upon sintering, the morphology and elemental composition of the KNN samples were investigated by FE-SEM. The fracture section of the KNN obtained from mixtures activated by varying RBP and with varying calcination rates are presented in Fig. 4. All samples show a dense microstructure with cube-like grains irrespectively of the synthesis conditions. Moreover, a lower dimension range for the obtained structures is evident for the samples obtained at either lower calcination rates or higher RBP. The average dimension of the observed structure appears to increase in the order: BP 10 @ 3°Cmin−1<BP 10 @ 10°Cmin−1<BP 5 @ 3°Cmin−1<BP 5 @ 10°Cmin−1. On the other hand, other smaller structures longer and with rounder corners are observed especially in the ceramics obtained with lower RBP and higher calcination rate (Fig. 4d, circled area), and they are indicative of secondary phases formation. The rounded agglomerates could be explained by the formation of liquid phase during the reaction of alkali elements with the moisture and CO2 from the atmosphere [18] or an incomplete transformation of the intermediate phase into KNN.

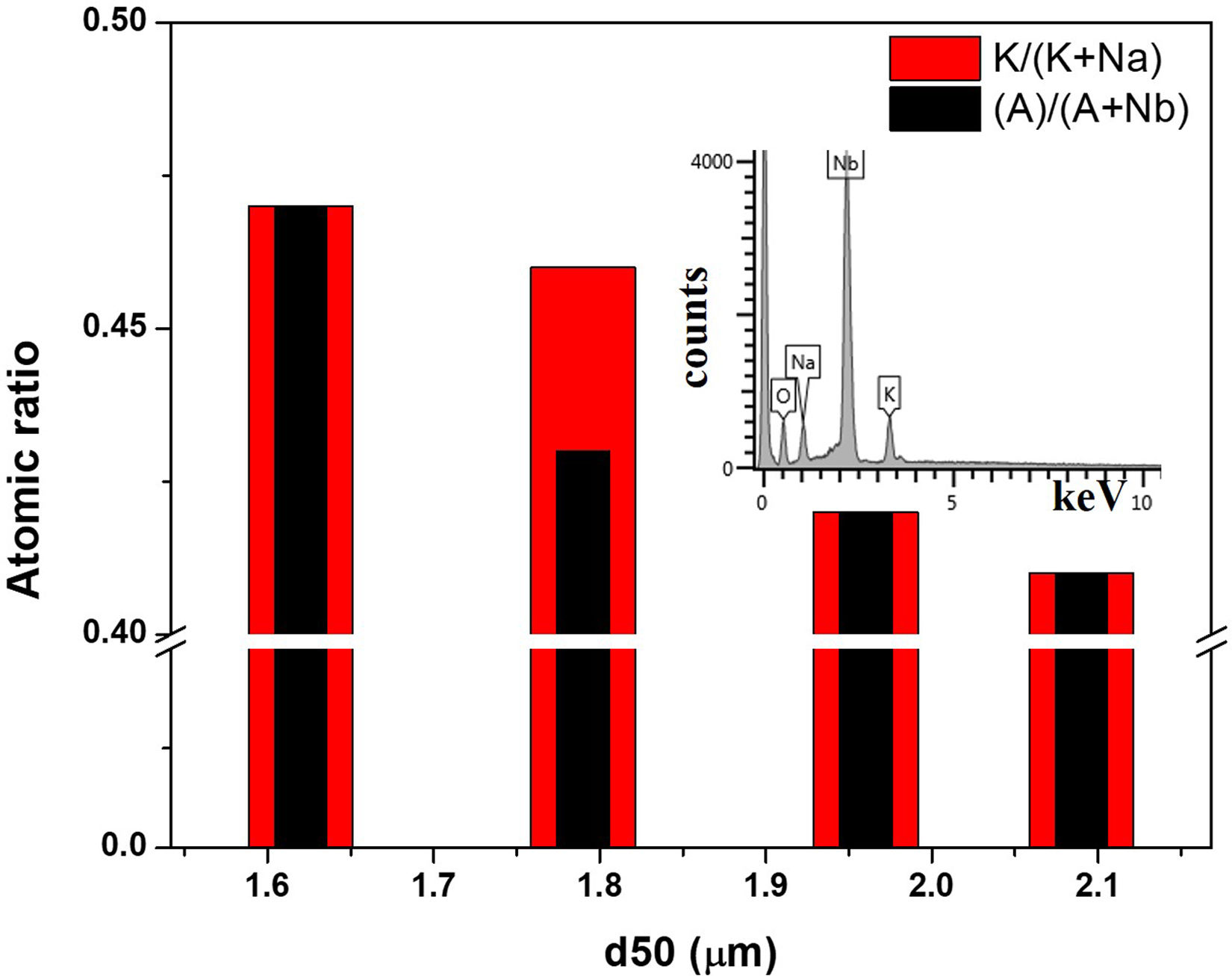

The final properties of the KNN ceramics depend greatly on the formation of secondary phases and K content from total alkaline one, as it is known that K ions have lower diffusion rates. The elemental analysis was performed by using an energy dispersion X-ray spectrometer (EDS). The results indicated a homogeneous distribution of all elements, and that stoichiometry varied depending on the ball milling. In this respect, Fig. 5 depicts both the alkaline content (A) and the K content from the total alkaline elements for the samples obtained in varying conditions of RBP and calcination rate.

Both the total alkaline elements content and K content appear to decrease as the average particle size of the calcined activated mixture increases, which is due to slower decomposition and reactivity of larger particles, in agreement with the TG results. Thus, by decreasing the particle size from 2.1μm to 1.6μm, the K content increases from 41% to 47%.

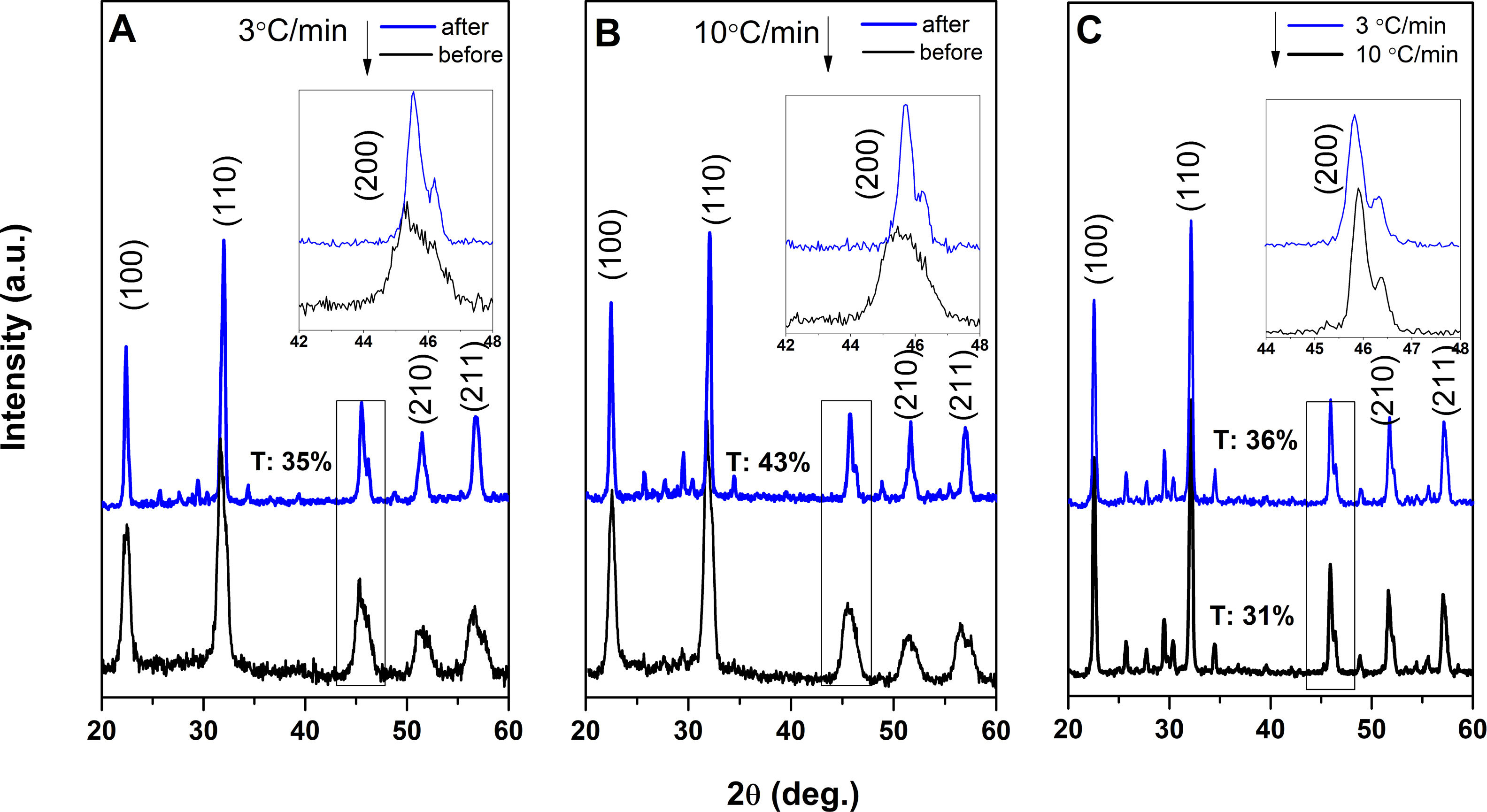

The XRD patterns were studied for the KNN in the varying RBP and calcination rates. The calcined mixture reactivity and KNN formation was first studied with the calcination rate before and after sintering, as shown for the RBP 10:1 mixture in Fig. 6a and b. All spectra present a sharp (110) plane at about 32° of maximum intensity indicative for the perovskite structure, beside other peaks in the 2θ range 22–30° which are assigned to the secondary phase K6Nb10.8O30. The peaks for the secondary phase are found to be related to the synthesis conditions, that is, they are the lowest for smaller particle size and calcined at lower rate, according to the XRD spectra in Fig. 6. The secondary phase content retrieved showed to increase in the order RBP 10@3<RBP 10@10<RBP 5@3<RBP 5@10 (where 3 and 5 refer to heating rate °Cmin−1 during calcination), namely from 7% to 15% and it is corresponding to an increase in the particle size of the calcined mixture from 1.6μm to 2.1μm. A careful balance of the reactant proximity and smaller particle size needs to be taken into account on the improvement of the pure phase formation and to lower the alkali volatilization.

The piezoelectric performance of KNN lead-free ceramics is very susceptible to phase structures. For most modified KNN-based materials, the co-existence of orthorhombic (O) and tetragonal (T) phases around room temperature could significantly enhance piezoelectric response. The fraction of co-existing phases tetragonal and orthorhombic ones can be found by Rietveld refinement. The formation of KNN is evidenced by the peak located at 45°, corresponding to the O-T co-existence, that increase in intensity and show a marked split upon sintering, into a first peak (200) for O/(002) for T and a second peak assigned to (200) for T/(020) for O phase, respectively. The fraction of tetragonal phase is indicated in XRD spectra in Fig. 6 for each synthesis condition. It is shown that the tetragonal fraction varied from 35 to 43.8% for the mix milled with 10:1 RBP and from 35.6 to 31.5% for those milled with 5:1 RBP. As it may be observed, the highest fraction of tetragonal phase corresponded to RBP 10 calcined at 10°Cmin−1.

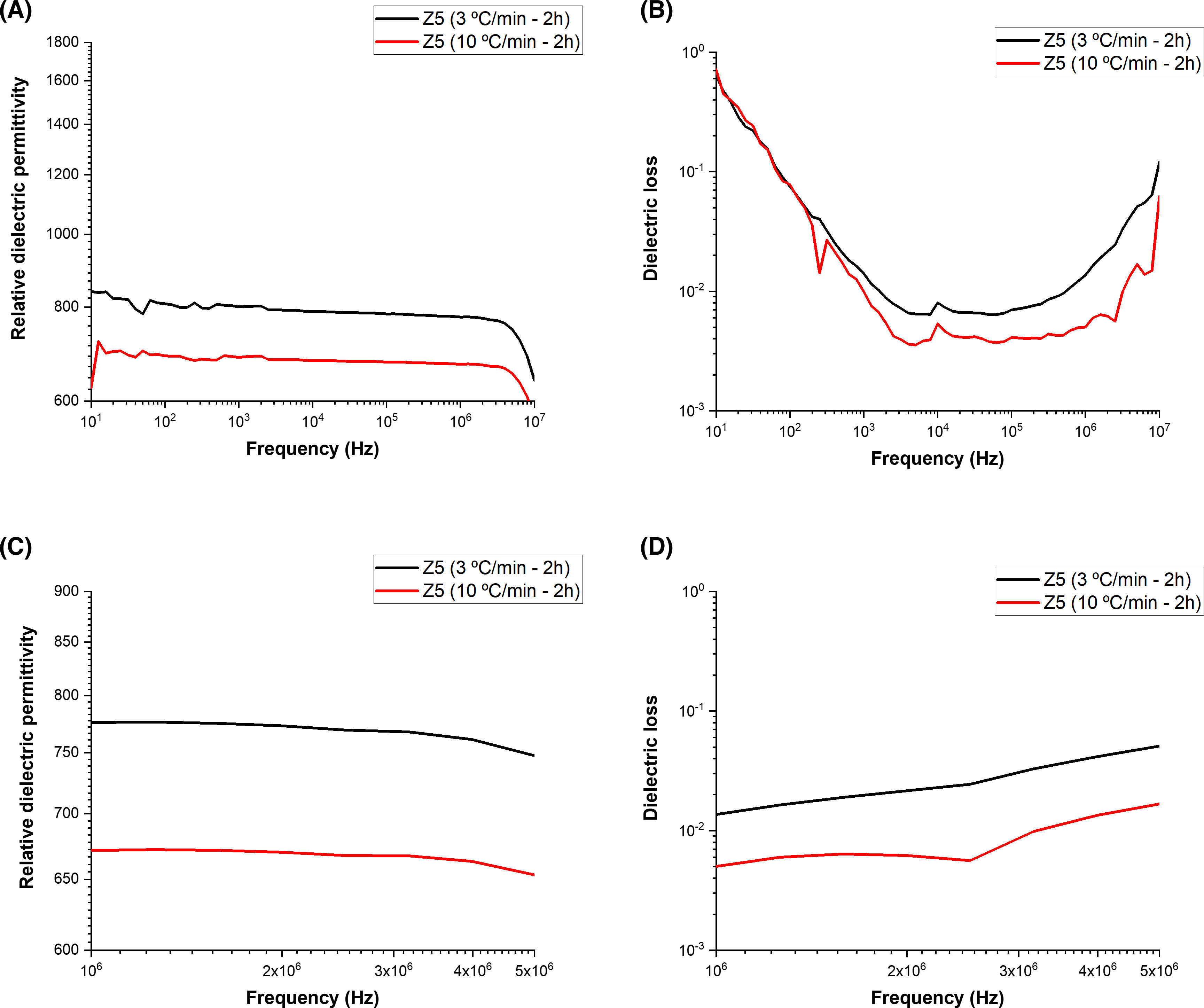

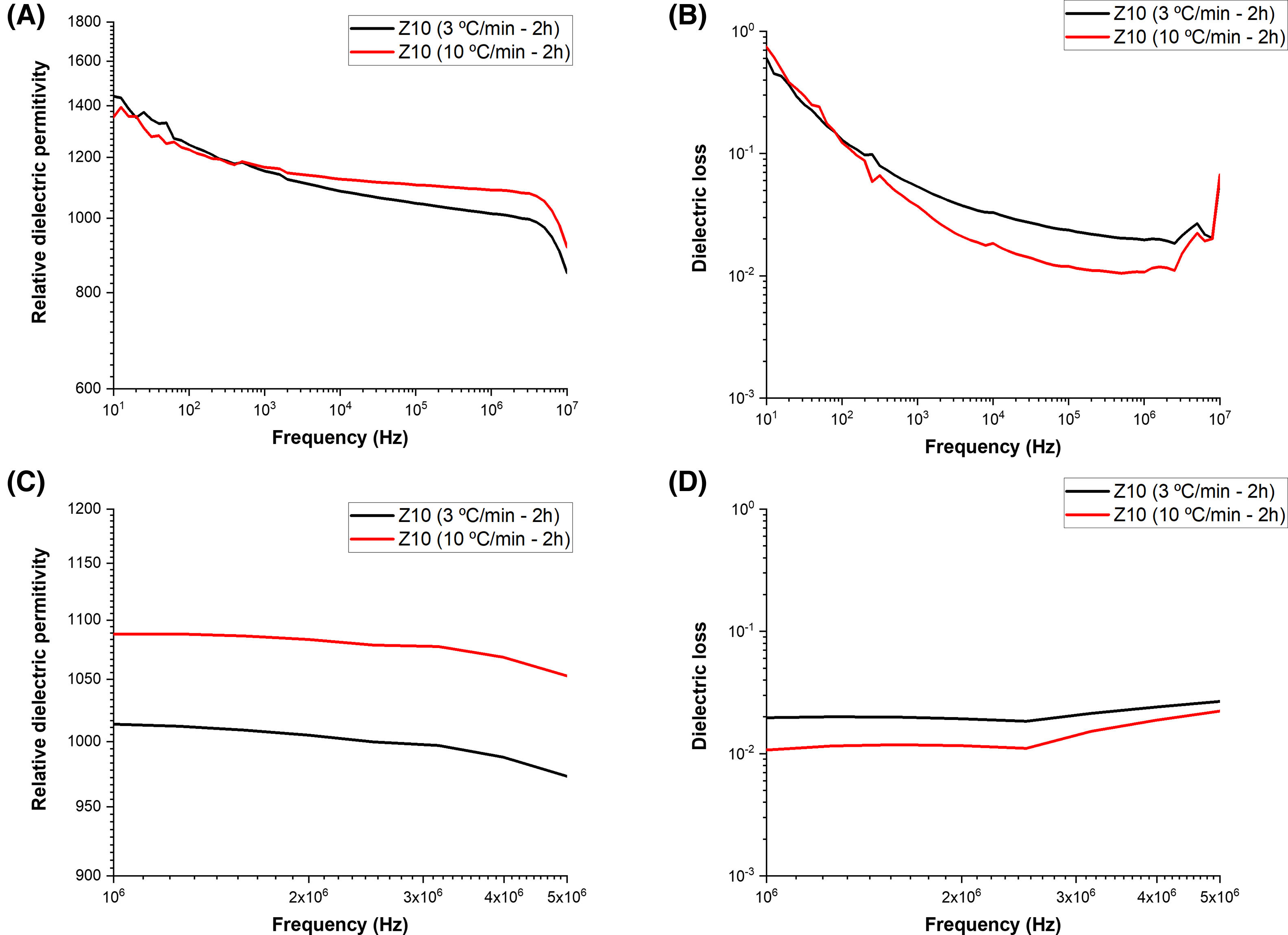

To check the effect of the phase co-existence and secondary phase presence on the electrical properties, the wide frequency range of the relative dielectric permittivity was recorded as shown in Figs. 7 and 8. The ceramics showed similar behavior irrespective of ball-to-powder ratio. The relative dielectric permittivity of the samples prepared with RBP 10:1 was similar and higher, irrespective of the calcination rate. On the other hand, lower but more stable values were recorded for the samples prepared with a RBP ratio 5:1. The relative dielectric permittivity recorded in the short frequency range averaged 1000 and 1060 for the samples prepared with RBP 10:1 and calcined at 3°Cmin−1 and 10°Cmin−1, respectively, while the samples prepared with RBP 5:1 exhibited values averaging 750 when calcined at 3°Cmin−1 and 660 when calcined at 10°Cmin−1. These values are consistent with those reported in the literature for this type of material [19–21]. The dielectric losses were recorded below 0.1 for the samples prepared with BP 5:1 and below 0.01 for the samples prepared with RBP 10:1, the smallest losses being exhibited by the sample prepared with RBP 10:1 and calcined at 10°Cmin−1. The obtained dielectric results indicate smaller particle ceramics exhibit higher dielectric constant and agree with the particle size adjusted by the RBP ratio and calcination rate. Relative dielectric permittivity values above 1000 and dielectric losses around 0.01 are typical of most piezoelectric materials [22], thus indicating a RBP ratio of 10:1 and calcination rates as 10°Cmin−1 are preferable synthesis conditions for KNN-based ceramics.

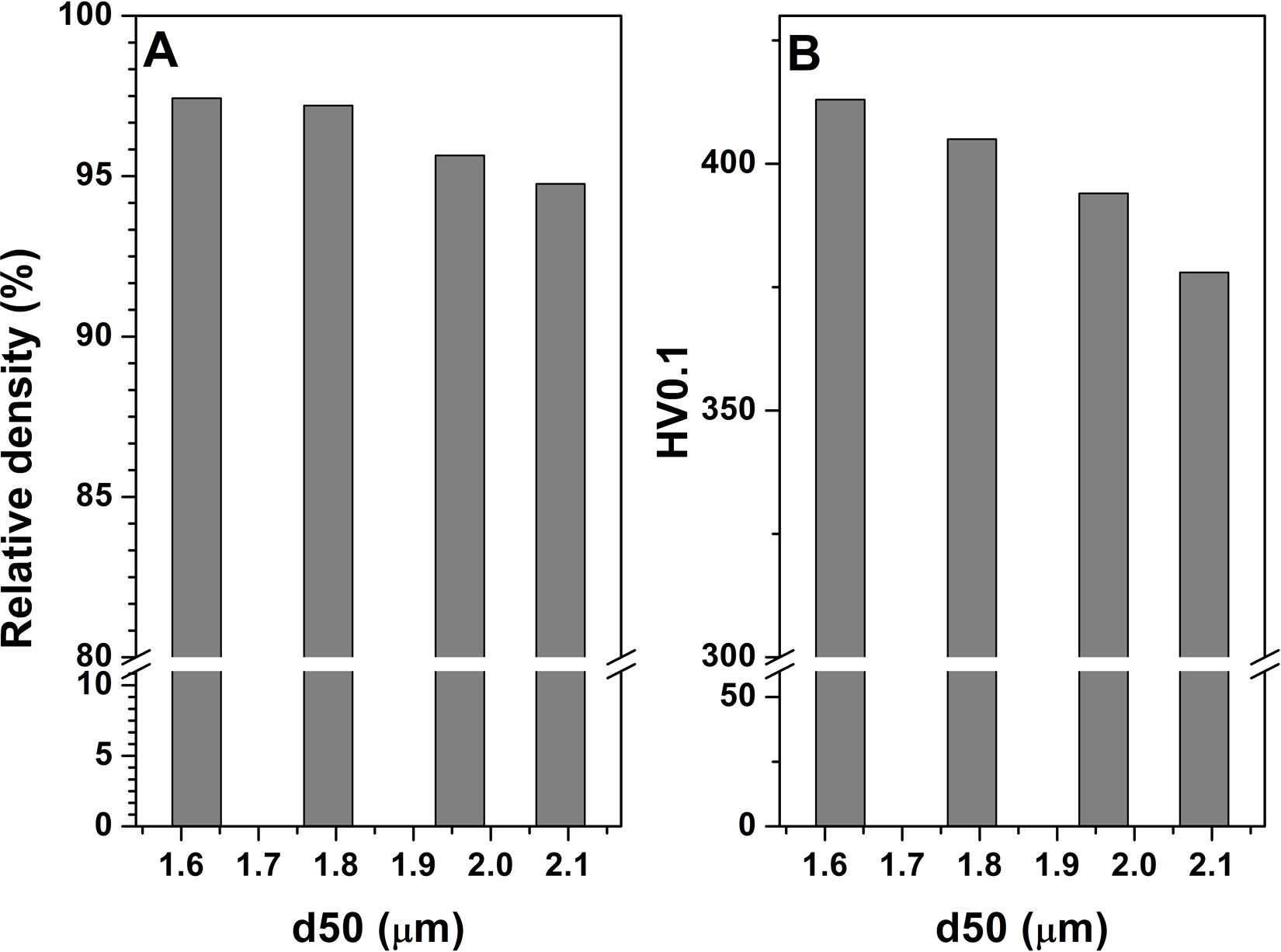

The Archimede density measurements indicated a high densification of the KNN ceramics obtained by the combined approach – mechanical activation–calcination as shown in Fig. 9a. By decreasing the average particle size of the calcined mixture from 2.1μm to 1.6μm, the relative density with respect to the theoretical one [23] increased from 94.76% to 97.43%. Similar relative density values were reported for KNN ceramics obtained with RBP 10:1 at lower calcination temperatures however, double calcination was required [18].

There are only a few publications addressing the mechanical properties of KNN-based ceramics [24–26]. In this work, the mechanical properties of the KNN ceramics were evaluated by microhardness measurements under 0.1kg load (HV0.1). The HV0.1 evolution with the average particle size induced by ball milling and calcination is presented in Fig. 9b. It is observed that HV0.1 increases with 10% up to 413μm with the decrease in particle size from 2.1μm to 1.6μm, which could be explained by the formation of higher fraction of pure phase and densification.

Investigation of the fracture behavior of these ceramics is important to improve the reliability and to assess the lifetime of piezoelectric devices [27,28]. It is known that fracture toughness depends on many factors, including microstructure, composition and crystallographic phases [29,30]. The fracture toughness of the obtained KNN-based ceramics was investigated using indentation fracture method. In our work, the KIC of the KNN obtained by RBP 10:1 increased from 1.42 to 1.82MPam1/2 by decreasing the calcination rate from 10 to 3°Cmin−1, in agreement with other reports [24,31].

ConclusionsKNN-based ceramics were obtained by a combined approach including a mechanical activation by ball milling of downsized precursor mixture and varying the calcination rate. Namely, the ball-to-powder ratio was varied from 5:1 to 10:1 and the calcination rate from 10 to 3°Cmin−1. The results indicate an important effect of synthesis conditions on the properties of the obtained KNN ceramics due to varying decomposition and reaction formation kinetics induced by the particle size and heating rate. Lower secondary phase content together with higher fraction of tetragonal phase was induced by increasing RBP to 10:1. The highest tetragonal fraction was further adjusted by using 10°Cmin−1 calcination rate at 800°C. The relative density improved up to 97.43% while the microhardness HV0.1 increased up to 413 by adjusting the particle size to the lowest value around 1.5μm. The dielectric properties were found to vary in the order: RBP 10 @ 3°Cmin−1<RBP 10 @ 10°Cmin−1>RBP 5 @ 3°Cmin−1>RBP 5 @ 10°Cmin−1, in agreement with the tetragonal phase content evolution.

This publication is part of the grant PID2021-128548OB-C21&C22 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF/EU”, and the grant CNS2023-144190 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR”. CIGRIS/2022/077 project funded by Generalitat Valenciana.