Fused filament fabrication (FFF) is one of the most competitive additive manufacturing technologies which allow easy component customization for several sectors. Its application to the ceramic field is rapidly growing addressed by formulating high-loading composites in several binder systems which after the printing process, they are removed by a two-step debinding process. In this work, new granules and filaments of Al2O3 have been produced using a two-component binder system, consisting of polylactic acid (PLA) and polycaprolactone (PCL). Al2O3 feedstock is printed by FFF obtaining complex 3D structures and after a thermal one-step debinding and sintering cycle 100% Al2O3 components is obtained with a relative density of 96%.

The mixing process is based on a colloidal route where the ceramic particle surface modification improves its interaction with the binder. This improvement brings the possibility to increase the ceramic load in the composite up to 48vol.%. Oscillatory melting rheology was measured to simulate the printing process. The incorporation of 25vol.% PCL in binder is enough to modify the flow of the melt composite, enlarging the plastic solid-like flow where the Al2O3 composites are suitable to flow through the nozzle, and build adequate 3D structures using high-loaded feedstocks.

La fabricación por filamento fundido (FFF) es una de las tecnologías de fabricación aditiva más competitivas que permite la personalización de componentes para varios sectores. Su aplicación en el ámbito cerámico crece rápidamente, desarrollando compuestos de alta carga inorgánica en varios sistemas aglutinantes que, después del proceso de impresión, se eliminan mediante un proceso de debinding en dos pasos. En este trabajo, se han producido nuevos gránulos y filamentos de Al2O3 utilizando un sistema aglutinante de dos componentes, que consiste en ácido poliláctico (PLA) y policaprolactona (PCL). La materia prima de Al2O3 se imprime mediante FFF obteniendo estructuras 3D complejas y, después de un ciclo térmico de debinding y sinterización en un solo paso, se obtienen componentes 100% de Al2O3 con una densidad relativa del 96%.

El proceso de mezclado está basado en el uso de rutas coloidales donde la modificación de la superficie de las partículas cerámicas mejora su interacción con el aglutinante. Esta mejora permite aumentar la carga cerámica en el compuesto hasta un 48% en volumen. Finalmente se midió la reología en fundido oscilatoria para simular el proceso de impresión. La incorporación del 25% vol de PCL en el aglutinante es suficiente para modificar el flujo del compuesto fundido, ampliando la zona plástica donde los compuestos de Al2O3 tienen las características adecuadas para fluir a través de la boquilla y construir estructuras 3D con compuestos de alta carga.

Orthopedic disorders have increased intensely over the last century mainly due to the aging population. Bones have healing potential, but some factors such as advanced age or lack of bone density can adversely affect the bone healing process [1]. Orthopedic tissue engineering is a multidisciplinary research field, which involve several solutions to the bone defect issues creating different alternatives such as synthetic bone substitutes [2]. In addition to the biological and biochemical requirement of this synthetic bone substitutes being biocompatible, osteoconductive or osteointegrative, a key requirement for bone regeneration is a porous scaffold that mimic the in vivo cell environment and allows for cells to migrate, proliferate or differentiate [3]. In orthopaedics, additive manufacturing (AM) emerges as a technology with extensive benefit in surgical applications. This fabrication method provides models and medical devices which help surgeon during the surgery of the patient, sensors and external prothesis. It easily produces specific custom orthopaedic implants such as screw, plates and protheses [4]. Related to the biomaterial the implants are made of, in general terms soft tissue implants employed in cartilage or ligaments are manufactured of polymers, and novel metals, while hard tissue implant for bones, knee and hip joints imply utilization of bioceramics and composites [5]. Bioceramics appeared as a potential substitute for hard tissue engineering especially for bone healing application. Bioceramics including zirconia, alumina, hydroxyapatite, and bioactive glass has been widely explored in the design of tissue engineering scaffolds due to its excellent mechanical strength, biocompatibility, chemical stability, corrosion restriction behavior, and wear resistance [6].

Alumina belongs to the family of bioinert bioceramics, and it has 45 years of clinical record in orthopedics. Its bioinert nature makes it especially favorable for orthopedic and dental application [6]. Mainly due to its outstanding wear resistance, alumina has often been used for worn surfaces for joint replacement protheses. Alumina is typically used in the manufacture of femoral heads for hip substitution implants and knee replacement implants wear plates [7]. However, as a ceramic material, alumina prothesis presents the common limitation in the processing, with a lack of accessible technologies to customize its structure to the final patient. The introduction of AM technologies into the manufacturing of alumina prothesis provides new possibilities for solving these limitations including customization and a cost reduction respect to traditional manufacturing methods [8].

Different AM techniques have been reported to process customized alumina components with high relative densities. Most of the current research in three-dimensional (3D) ceramics printing focuses on indirect methods where the main efforts are on the development and customization of a ceramic-based feedstock. With this technology, a post-processing step of debinding and sintering is required in order to consolidate the ceramic structure [9]. A clear example are the techniques of stereolithography (SLA) and digital light processing (DLP) which are generally employed for the fabrication of bulk ceramic materials using highly loaded ceramic suspension with photocurable resins [10]. Some authors have demonstrated the use of SLA technique to design and fabricate alumina pieces with a density of 98% after a unique thermal sintering cycle using commercial photocurable resins with 80vol.% of Al2O3[9] or DLP with slurries with 52vol.% of Al2O3 micropowder obtaining relative densities of up to 98% after a double thermal debinding-sintering process [11]. Otherwise, direct ink writing (DIW) appear as an emerging low-cost additive manufacturing technique, based on the design of highly loaded inks that are extruded through a nozzle and depositing on the substrates in ambient conditions. Some examples of alumina-based materials processed by DIW can be found in the literature using as feedstock suspension with up to 60vol.% of ceramic load obtaining up to 93% of relative density after sintering [12–15].

Fused filament fabrication (FFF) method has appeared as an indirect AM technology to manufacture complex structures directly by layer by layer thermal extrusion using a composite thermoplastic filament as feedstock. Alumina composites with a low ceramic load (up to 1.5wt.%) have been printed by FFF using PLA as thermoplastic vehicle [16] or polyamide [17]. However, when the purpose is to obtain a dense alumina component, the solid content in the composite must be notably increased. Some examples in the literature highlight the 3D printing of dense Al2O3 with injection moulding binders, such as EVA with a 50vol.% of Al2O3, achieving 98% density after a debinding cycle of 60h and a sintering cycle of 45h [18], or others, to manufacture fully dense 3D objects with also high relative density (≥95%) after a proper two-stage debinding regime of solvent debinding in cyclohexane and a thermal debinding up to 850°C [19]. Alternative water soluble binders, as polyethyleneglycol and polyvinylbutyral, have been proposed and mixed up to reach 55vol.% of alumina in the feedstock to obtain 98% density, combining aqueous solvent debinding and thermal debinding [20]. Commercially, Al2O3 filaments can be found, such as Zetamix (Nanoe, France) with a 52vol.%. Commercial filaments have been tested by researchers printing and sintering 3D pieces with 95–98% of density after the combined chemical and thermal debinding [21,22].

Summarizing, most of the reported investigations on Al2O3 feedstock for FFF technology is generally focused on the development of compositions based on thermal mixing and, injection molding binders with low molecular weight, which provides a high fluency of the melted composite during printing and removal during the chemical and thermal debinding processes. Recently, other ecofriendly alternatives have been proposed based on the use of bioresources, such as the polylactic acid (PLA) base composites, to obtain high printing quality 3D objects [23]. Surface quality and resolution of printing mainly depend on the melt composite flux, and in this sense, the PLA-based composites allow taking advantage from a thick melt. However, the fabrication of the sinterable feedstock based on this polymer is still a challenge since the high solid load required makes the filaments brittle and unprintable. According to the literature, blending PLA with other flexible polymers is an effective method to improve the toughness and increase the ductility of PLA. With a Tg of −60°C, poly(ɛ-caprolactone) (PCL) is a biodegradable polyester extensively used to increase the flexibility of PLA. The highlighted drawback of these blends is the low compatibility between both polymers, but there are strategies, such as the use of block copolymers or nanofillers, to improve the uniformity of the mixtures [24].

This work is focused on establishing a suitable thermoplastic PLA/PCL blend, as a sustainable alternative to provide the Al2O3 printing, and a fully-thermal process for the debinding and the sintering, reducing time and costs. The objective is to consolidate the 3D Al2O3 parts, while improving flexibility and toughness to the printing feedstock, both granule and filament-shaped. For that, the miscibility of the PLA/PCL blend was studied emphasizing the role of Al2O3 nanoparticles as compatibilizer of the mixtures, in terms of dispersion homogeneity of the inorganic charge in the composite, and the viability and resolution of the printing and sintering of 3D Al2O3 parts.

Material and methodsCeramic filaments were processed following a colloidal approach to improve the interaction between the thermoplastic matrix and Al2O3 particles, increasing the inorganic fraction/particles in the feedstock. As-received Al2O3 powder (Martoxid MR70, Huber, Germany) with D50 of 840nm was used in this study for the fabrication of sinterable feedstock. Colloidal processing includes the study of the surface modification of Al2O3 particles in aqueous media, preparing high-loaded suspensions, which will be blended with a thermoplastic matrix, and finally, the extrusion to obtain the filament. The processing method described in this work is under the patent [25]. Fig. 1 summarizes the processing steps followed for the feedstock fabrication.

Study of thermoplastic mixturesPolylactic acid (PLA, 2003D with a D-isomer content of 4.25% supplied by Natureworks®, USA) and polycaprolactone (PCL 6800 supplied by Capa™) were dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF, Panreac, Germany) with a concentration of 80g/L. Solutions were mechanically stirred and mixed. Different ratios of PLA/PCL were prepared to study the miscibility between both polymers. Pure PLA, PLA/10PCL, PLA/25PCL, PLA/50PCL, PLA/75PCL, and pure PCL solutions (PLA/PCL ratio indicated in volume) were studied.

The PLA/PCL mixtures were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR). A Perkin Elmer FTIR spectrometer equipped with a total attenuated reflectance device (ATR) was used to obtain the IR spectra of the samples that were scanned in the region of 4000 to 600cm−1. The results were shown in transmittance (%) and normalized to the highest peak intensity for their comparison. The flow curves of PLA/PCL solutions were measured using a Haake Mars60 rheometer (Thermo Scientific, Germany) with a double-cone plate fix of 60mm diameter, an angle of 2° (DC60-2°) and a 0.085mm gap. Measurements were made on control rate (CR) and control stress (CS) modes. For the CR test shear rate (γ) was increased from 0 to 1000s−1 in 3min, dwelling at 1000s−1 for 1min and shearing down to 0s−1 in 3min. For CS tests shear stress (ꞇ) was increased from 0 to 6Pa in 3min and down to 0Pa at the same time without any stress dwell. All flow curves were performed at room temperature.

Composite feedstock fabrication and characterizationAlumina-containing filaments were prepared and granulated as described elsewhere [27]. Experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 1. Surface-modified Al2O3 nanopowders by the adsorption of polyethilenimine (PEI, Aldrich, Germany) were blended and dispersed in PLA/PCL solutions, with 5wt.% of polyethylene glycol (PEG 400, Merck, Germany) as plasticizer additive. The thermoplastic matrix was formulated with different PLA and PCL ratios: PLA, PLA/10PCL, and PLA/25PCL (in volume) to produce the composites. Inorganic content of 48 and 44vol.% Al2O3, in volume regarding the thermoplastic matrix, were considered. Table 1 summarizes the formulations prepared in this work, indicating the nomenclature used for each composite. Particle-thermoplastic suspensions were granulated after wet mixing using a rotary evaporator. Granules were extruded into filaments at 165°C using a screw extruder (FILABOT EX2, USA) equipped with a nozzle of 1.75mm. The extrusion temperature was selected from the thermal analysis of granules composites, which show the same melting temperature regardless the solid content or thermoplastic matrix.

Differential thermal analysis and thermogravimetry (DTA-TGA) tests were carried out for granules and filament composites. Measurements were performed under argon (Ar) atmosphere (40ml/min) using an STD Q600 analyzer (TA Instruments, USA) with heating and cooling rates of 5°C/min. TG derivatives curve (DTG) was calculated to set the filament degradation rate regarding the solid content and PLA/PCL ratio.

Rheological characterization of the thermoplastic composites was carried out using a Haake Mars60 rheometer (Thermo Scientific, Germany) equipped with an electrically heated plate/plate configuration of 25mm diameter and 1mm gap. Plates were heated up to the melting temperature of the composite (Tm) before placing the grounded filaments onto the lower plate. Once the upper plate reached the measuring position, the excess material was removed from measuring tools with a metallic scraper suiting the sample to the measuring plate size. Dynamic amplitude sweep (AS) in control deformation mode, ranging from 0% to 100% with a set temperature over Tm and frequency of 1Hz were made to determine the elastic (G′) and loss modulus (G″). The evolution of G′ and G″ was determined by a temperature sweep (TS) test for temperatures ranging between Tm–Td, maintaining fixed frequency (1Hz) and deformation (%) values inferred from AS curves. Finally, the frequency sweep (FS), ranging from 0.01 to 100Hz, was performed at two temperatures using different deformation (0.1, 1, and 2%) to determine the shear rate interval in which the composite gets viscous flow to be printed.

The functional groups of the composites (granules and filaments) as well as the pure PLA, were analyzed by ATR-FTIR, as described above. The phase structures and polymer crystallinity present in composites (granules and filaments) and sintered samples were identified by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using Bruker D8 Advance (Germany) diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation 1.54Å and an accelerating voltage of 40kV and a current of 40mA.

Filaments were cut to obtain 10mm length. Filament was sectioned at different times of the extrusion process to determine the density by the Archimedes method in water. An analytical scale with a precision of 0.1mg (Mettler Toledo AB104, Belgium) was used to weigh the samples in air and immersed in water at 25°C. At least 5 samples were measured for a given value. Density values refer to the theoretical density calculated following the law of mixtures and using the composition derived from TGA.

A field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM Hitachi S-4700, Japan) was used to evaluate the particle distribution of composites. Granules were embedded in an epoxy resin, whereas the fracture surface was observed for filaments.

PrintingScaffolds were printed using a 3D printer (Prusa I3, Czech Republic) with a nozzle diameter of 0.5mm and Ultimaker Cura 4.2 software. The printing temperature was selected from the thermal analysis of filament composites, which show the same melting temperature regardless of the solid content or thermoplastic matrix. For all the structures, a constant feed rate of 40mm/s and a bed temperature of 60°C were maintained throughout the printing process. Several designs were considered.

Scaffolds with different geometry, infill, and printing patterns were printed for various purposes. For DIL analysis, square scaffolds with 100% infill, a linear pattern, and a 1cm edge. Validating the sample consolidation, circular, rectangular, and square scaffolds were printed using a linear and gyroidal pattern. Details of printed samples are described in “Printing of Al2O3 filaments” section.

Sintering and 3D parts consolidation and characterizationDilatometry (DIL) measurements were carried out using a dilatometer Netzsch 402E/7 (Germany) with a vertical configuration to settle the sintering conditions. DIL analysis was performed under pre-sintered scaffolds with 100% infill in order to maintain contact between the pushrod and the sample.

Pre-sintering was performed under Ar and air atmosphere. Samples treated under Ar atmosphere were heated at 1°C/min up to 800°C for 20min. On the other hand, air-treated samples were heated at 1°C/min up to 600°C under Ar flow, then heated up to 800°C for 20min in an air atmosphere.

DIL measurements were carried out at 5°C/min up to 1550°C under air atmosphere. Shrinkage behavior was studied on XY axis (perpendicular to the printing direction) and Z-axis (deposition direction).

Finally, samples were consolidated by one-step thermal treatment to perform a time-and-cost-effective debinding and sintering process under air atmosphere. Thermal cycle consisted on heating the samples at 1°C/min up to 600°C; then, the heating rate was increased to 3°C/min up to 1500°C with a holding time of 2h.

The 3D sintered samples were measured before and after sintering to determine the shrinkage degree, while the density after sintering was determined by the Archimedes method, as described above. A field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM Hitachi S-4700, Japan) was used to evaluate the consolidated microstructure.

Results and discussionPLA/PCL thermoplastic matrixThe interaction of PLA and PCL mixtures was studied to obtain a suitable thermoplastic matrix for material extrusion of sinterable ceramic filaments, in order to make it handle, spoolable, and printable. Both polymers were dissolved in THF at a concentration of 80g/L. Mixtures with different concentrations of PLA and PCL were prepared and labeled as PLA, 90PLA-10PCL, 75PLA-25PCL, 50PLA-50PCL, 25PLA-75PCL, and PCL (amount expressed in vol.%). To study the stability of the mixtures and their miscibility a short study at different times after mixing (as-mixed, 2h, and 24h) was carried out. Fig, 2a offers a visual inspection of PLA/PCL mixtures: 75PLA-25PCL, 50PLA-50PCL, 25PLA-75PCL. It can be seen that in as-mixed conditions, the three mixtures seem homogeneous since there are no visual signs of separation between the polymers. However, after 2h at rest, the phases start to segregate in the polymeric blend. After 24h of mixing, a clear interface between PLA and PCL is observed. Due to the density differences between PCL and PLA, the cloudy (on the bottom) phase corresponds to PLA, while the translucid (on top) corresponds to PCL.

(a) Visual inspection of PLA/PCL solutions in THF at a concentration of 80g/L for PLA75PCL25, PLA50PCL50 and PLA25PCL75 at different times: as mixed, after 2h and 24h at rest. (b) Flow curves of PLA/PCL mixtures after mixing and blending. (c) Vacuum-dried PLA/PCL mixtures: 75PLA-25PCL and 25PLA-75PCL. (d) FTIR spectra of thermoplastic mixtures and details of CH band and CO band.

The rheology of the as-mixed solutions was measured and the viscosity curves can be found in Fig. 2b. The 80g/l solutions of PLA, PCL and the mixtures exhibit a Newtonian behavior. However, differences between the viscosity measured under CR and CS conditions can be noticed, which could indicate that polymers in solution maintain a strong interaction and a given microstructure. It is reported than the ratio PLA/PCL strongly determines the orientation of their fiber microstructure, conditioning the flow of the solutions, i.e. during casting [26]. Only the 75PLA-25PCL solution exhibits a continuous viscosity evolution for the proposed shear rate range. Plots also show that the molecular weight of both polymers has a significant impact on the rheological properties. Specifically, at the same concentration, PCL exhibited a viscosity of 80mPas, while PLA exhibited a higher viscosity of 200mPas. The viscosity of the mixtures fell within this range and varied depending on the content of PLA and PCL. The obtained range of viscosities for the polymeric mixtures are suitable for achieving uniform mixing with the Al2O3 nanoparticles and to provide an excellent dispersion of the nanoparticles within the polymer blend.

From this short study of the PLA/PCL mixtures, it can be concluded that PLA and PCL are immiscible although their interfacial tension is low enough so that, through constant stirring, its rheology shows a good integration of both polymers under stirring. Based on the lower interaction among polymers, the mixture of 75PLA-25PCL can be considered a limit to process the Al2O3 feedstock, and hence this PLA/PCL ratio was selected as up-limit for later studies.

Mixtures were vacuum-dried (Fig. 2c). An island-type morphology is observed, in which the PLA is concentrated in the center (bottom of the flask), and the PCL surrounds it. This demonstrates the non-uniformity of the blend structure after solvent evaporation and drying. Fig. 2d presents the FTIR spectrograms of pure PLA, PCL, and their mixtures. As seen from the spectrograms, carbonyl stretching (CO) vibration of PLA is seen as a sharp peak at 1750cm−1, while for pure PCL, CO band is observed at 1723cm−1, which is a lower wavenumber than PLA. At higher wavenumber, it can be seen CH stretching bands at 2995cm−1 belonging to PLA and at 2944cm−1 and 2865cm−1 for PCL. Mixtures increasing/decreasing in the intensity of the main bands depending on PLA/PCL ratio in the mixture. In this way, the addition of PCL to the PLA solution decreases the intensity of PLA, and a second band appears that corresponds to that of PCL. Additionally, as no new bands/peaks were observed on the spectra of PLA/PCL mixtures, it can be concluded that no new functional groups are formed. The fact that PLA and PCL peaks can be clearly differentiated in the mixtures confirms the immiscibility of the PLA/PCL mixtures and suggests that each polymer maintains its properties.

Granules and filament fabricationA cationic polyelectrolyte, PEI, was chosen for modifying Al2O3 particles in high concentrate suspensions, providing homogeneous distribution of the inorganic load in the PLA and PLA/PCL matrix, by previously making sure there was a stable dispersion of Al2O3 particles in the THF solution of thermoplastics. It is reported elsewhere by Ferrandez-Montero et al. that PEI could interact directly with the PLA matrix, which improves the anchorage of the polymeric chains with the particles throughout PEI-PLA bonding [27].

Mixtures containing 44vol.% Al2O3 particles with pure PLA, PLA/10PCL, and PLA/25PCL thermoplastic matrix were prepared by a colloidal approach using wet mixing. Rheological measurements from 0.1 to 1000s−1 shear rate were performed after milling, for 44Al2O3-PLA/10PCL and 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL compositions. Flow curves are shown in Fig. 3a.

From Fig. 3a, PCL addition has no significant effect on the rheology of concentrated suspensions. However, the addition of Al2O3 nanoparticles modifies the flow behavior of thermoplastic solutions from Newtonian to pseudoplastic behavior. Additionally, the 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL mixture exhibits a more remarkable pseudoplasticity than the 44Al2O3-PLA/10PCL solution. This can be attributed to a stronger particle–polymer interaction among modified-Al2O3 nanoparticles and the PCL.

At low shear rates, the suspensions achieve viscosity values of 2000mPas, providing high stability against the sedimentation of the particles at rest since the high viscosity maintains the particles suspended. Conversely, at high shear rates, viscosity decreases to values between 83 and 45mPas for PLA/10PCL and PLA/25PCL mixtures, respectively. Low viscosities are desired for high-shear processes. Additionally, viscosity values at 100s−1 of all suspensions are around 100–150mPas (PLA/10PCL 160mPas; PLA/25PCL 100mPas; 44Al2O3-PLA/10PCL 130mPas and; 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL 100mPas). It was reported in previous work that a viscosity (at 100s−1) close to 100mPas favors phase mixing and allows obtaining homogeneous composites after drying [27].

The suspensions were dried for solvent removal and granulated in a composite (Fig. 3b). It is worth noting that the different granules sizes can be adapted to adjust the granulometry of feeding powder to the extruder to improve the flowability. In Fig. 3b, a characteristic size distribution of the Al2O3-PLA/PCL granules in four fractions is shown. The 70wt.% are granules ranging 0.5–3.15mm while the others are distributed among the fine (<0.5mm) and the coarse (>3.15mm) fractions. Feeding and printing flow are highly influenced by the flowability of powder into the extruder head screw. Granules flowability strongly interacts with the extrusion process, and the fraction ranging 0.5–3.15mm has the optimum size for feedstock used at the hopper-printers. It is important to notice that a representative amount of granules of different fractions and considered compositions were calcined in air at 400°C, leading to similar values of Al2O3 contents. Consequently, whatever is the size of the fraction, granules have the same organic/inorganic ratio.

In order to explore the distribution of Al2O3 particles in the PLA-based matrix, SEM images of the cross-sections of the embedded granules were examined. Representative images for 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL granules are displayed in Fig. 3c and d. The Al2O3 particles are embedded in the thermoplastic matrix and fully covered by a PLA/PCL layer showing a homogeneous distribution of Al2O3 particles within thermoplastic, with no presence of agglomerates.

Granules were extruded to obtain filament with a 1.75mm diameter. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of filaments. It is noted that the composites with pure PLA matrix, although relative densities of the filaments are high, are too brittle to be spooled, obtaining rigid bars instead of filament. This is undesirable since the printing of bars does not allow continuous material feeding during printing. In contrast, it is noticeable that filaments containing PLA/PCL mixture exhibit improved flexibility than pure PLA matrix, obtaining homogeneous filament with a diameter of 1.71–1.73mm with a tolerance of ±0.15mm, able to be printed by conventional FFF printers. There is a relevant difference between the densities of the filaments of PLA/25PCL and PLA/10PCL matrices, the 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL filament being denser (99.4%). The composites 48Al2O3-PLA present extrusion issues since the composite flow within the screw is not homogeneous, causing discontinued feeding and problems of nozzle clogging during extrusion. This suggests that an inorganic load of 48vol.% Al2O3 is too high to ensure good melted flow behavior required to be processed by material extrusion printing.

Filament characteristics.

| Sample | Diameter, ∅ (mm) | ρtheo (g/cm3) | Relative density* (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 48Al2O3-PLA | 1.71±0.43 | 2.55 | 100.0 |

| 44Al2O3-PLA | 1.68±0.40 | 2.44 | 98.8 |

| 44Al2O3-PLA/10PCL | 1.73±0.13 | 2.43 | 90.4 |

| 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL | 1.71±0.15 | 2.42 | 99.4 |

Fig. 4b and c displays the SEM images of the cross-section of 44Al2O3-PLA and 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL filaments to determine the particle dispersion in the blend. The filaments are dense, reaching both filaments a relative density of ∼99%. Particles are well-dispersed and fully embedded/covered by the thermoplastics. The cross-section of PLA matrix composite exhibits a brittle fracture, opposite to that of the PLA/PCL matrix composite. In the 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL cross-section, both PLA and PCL fractions were easily identified. The PLA fraction corresponds to the dark phase (indicated with red arrows), while PCL is presented with fiber-like morphology (indicated with yellow arrows). PLA fraction has a brittle fracture, and PCL fiber/chain shows ductility. Then, the fiber-like morphology of PCL brings flexibility to the filament, reinforcing the PLA matrix.

XRD and FTIR analyses were performed to study the interaction produced between PLA and PCL chemical groups by adding the PEI-modified Al2O3 particles varying the solid load and the PLA/PCL ratio. Fig. 5a and b shows XRD results for 48Al2O3-PLA and 44Al2O3-PLA (0, 10, 25PCL) formulations for granules (G) and filaments (F), respectively.

Diffractograms of the granule composites confirm the presence of PLA, PCL and Al2O3 phases in the granulated feedstocks. No difference in the intensity of the peaks of PLA of different compositions means that the PCL does not affect the crystallinity of the PLA. The intensity of the PCL peaks, located at 21.4° and 23.7°, increases as the PCL fraction rises. Regarding the effect of solid content, no differences were found for pure PLA compositions containing 44 and 48vol.% Al2O3 which is related to a non-degradation effect by the particle incorporation in the polymeric matrix. The spectra of the filaments evidence the amorphization of the polymeric matrix due to the thermal extrusion process of filament fabrication since the reflection of the PLA and PCL crystallites disappears for all compositions.

The FTIR results for granules and filaments are shown in Fig. 5c–e and d–f, respectively. The most characteristic bands of PLA at 1755cm−1 are attributed to the carboxyl bond of the ester group being extremely sensitive to changes caused by polymer degradation or interaction with another component. This band decreases its intensity and is slightly displaced in the composites with increases in PCL and Al2O3 content, which is related to an interaction between the components of the composites PLA-PCL, PLA-Al2O3 etc., especially after the extrusion process. The band at 1723cm−1 is the principal of PCL, which increases with its presence in the composite. The existence of both polymers is also evident at the bands 2999cm−1 and, the 2944cm−1 and 2865cm−1, representing the CH2 stretching of PLA and the asymmetric/symmetric CH2 stretching of PCL, respectively, especially at the 44Al2O3-25PCL/PLA composition. The peak at 1643cm−1 is also observed for all spectra of granules and filaments (Fig. 5e and f), which has been previously reported as the band associated to a covalent bond between PEI stabilizer with the carboxyl group of the PLA, after thermal treatment above 60°C. The PLA-PEI mechanism of anchorage have been already reported by Ferrandez-Montero et al. [27] during a reactive extrusion, reinforcing the idea that a strong interaction occurs between the PLA ester group (R-COOR′) and the chemical group of dispersants (NH, NH2, N+…) during the composite preparation. Remarkably the 1643cm−1 band increases with the presence of PCL in the composites, which means that PEI interaction also occurs with the functional groups of PCL and even with PEG as was reported elsewhere [28].

In view of these results, it can be concluded that the variations observed in the composite bands show slight changes in the PLA and PCL polymers because of the presence of the PEI-Al2O3 nanoparticles. The surface modification of the Al2O3 nanoparticles using a cationic polyelectrolyte promotes the interaction between the hydroxyl (OH) and carboxyl (CO) groups of PLA and PCL with its amine groups (NH). This is beneficious for the well dispersion of the inorganic phase in the polymeric matrix but also to preserve this dispersion during the stress of extrusion and 3D printing process. Polymers bonding improves not only the strength of the polymer-Al2O3 union but also makes compatible the PLA and PCL. The PLA/PCL interaction observed by FTIR is associated with a better dispersion of both phases, as can be observed in the granule micrographs (Fig. 3c and d) and also at the filament cross-section (Fig. 4c), enhanced by the incorporation of the Al2O3 phase. This is in concordance with the literature work as a compatibilizer agent to increase the lack of miscibility between the two polymers [24].

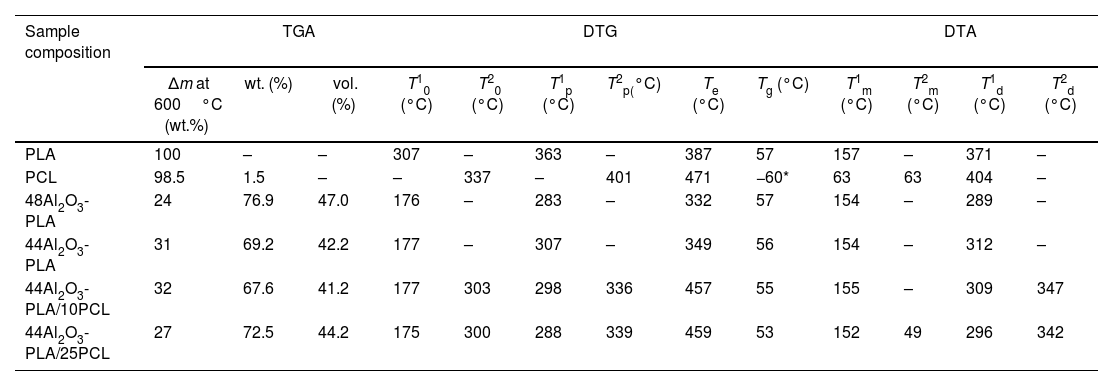

Thermal characterizations of Al2O3 thermoplastic granules were performed to establish the framework conditions for the printing process and debinding. The DTA-TGA defines the melting temperature of granules, Tm, which determines the temperature of extrusion and printing. The thermogravimetry analysis (TGA) and its derivate (DTG) describe the degradation process, defining the initial, final and maximum temperature of degradation of composite, T0, Te, and Tmax considered to design the conditions of the thermal post-processing. The TGA was also used to determine the solid load of the feedstock (granules and filaments). Representative results of DTA-TGA obtained for some of composite samples are included in Fig. 6 to illustrate the study, while Tables 3 and 4 summarizes relevant temperatures extracted from the DTA-TGA-DTG curves for all granules and filaments prepared for compositions in Table 1. DTA-TGA curves of pure PLA and PCL are included for comparison purposes.

Summary of the DTA-TGA-DTG results related to the characteristic temperatures of granules composites extruded at 165°C: the mass loss (Δm) at 600°C and the remained solid content of the granules* (in weight and volume); and the glass transition temperature (Tg), the melting temperature (Tm) and the degradation temperature (Td), the initial degradation temperature (T0), the maximum degradation temperature (Tp) and the ended degradation temperature (Te). Temperatures referred as T1 and T2 correspond to PLA and PCL peaks.

| Sample composition | TGA | DTG | DTA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δm at 600°C (wt.%) | wt. (%) | Vol. (%) | T10 (°C) | T20 (°C) | T1p (°C) | T2p (°C) | Te (°C) | T1g (°C) | T1m (°C) | T2m (°C) | T1d (°C) | T2d (°C) | |

| PLA | 100 | – | – | 307 | – | 363 | – | 387 | 57 | 157 | – | 371 | – |

| PCL | 98.5 | 1.5 | – | – | 337 | – | 401 | 471 | – | – | 63 | 404 | – |

| 48Al2O3-PLA | 24 | 76.8 | 46.8 | 174 | – | 262 | – | 323 | 58 | 152 | – | 265 | – |

| 44Al2O3-PLA | 31 | 69.9 | 42.6 | 176 | – | 304 | – | 346 | 59 | 152 | – | 309 | – |

| 44Al2O3-PLA/10PCL | 32 | 66.1 | 40.3 | 173 | 303 | 266 | 325 | 448 | 57 | 153 | – | 274 | 329 |

| 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL | 27 | 73.0 | 44.5 | 174 | 300 | 263 | 333 | 452 | 57 | 152 | 49 | 270 | 337 |

* Solid content extracted from DTA-TGA curves.

Summary of the DTA-TGA-DTG results related to the characteristic temperatures of filament composites, extruded at 165°C: the mass loss (Δm) at 600°C and the remained solid content of the filaments* (in weight and volume); and the glass transition temperature (Tg), the melting temperature (Tm) and the degradation temperature (Td), the initial degradation temperature (T0), the maximum degradation temperature (Tp) and the ended degradation temperature (Te). Temperatures referred as T1 and T2 correspond to PLA and PCL peaks.

| Sample composition | TGA | DTG | DTA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δm at 600°C (wt.%) | wt. (%) | vol. (%) | T10 (°C) | T20 (°C) | T1p (°C) | T2p(°C) | Te (°C) | Tg (°C) | T1m (°C) | T2m (°C) | T1d (°C) | T2d (°C) | |

| PLA | 100 | – | – | 307 | – | 363 | – | 387 | 57 | 157 | – | 371 | – |

| PCL | 98.5 | 1.5 | – | – | 337 | – | 401 | 471 | −60* | 63 | 63 | 404 | – |

| 48Al2O3-PLA | 24 | 76.9 | 47.0 | 176 | – | 283 | – | 332 | 57 | 154 | – | 289 | – |

| 44Al2O3-PLA | 31 | 69.2 | 42.2 | 177 | – | 307 | – | 349 | 56 | 154 | – | 312 | – |

| 44Al2O3-PLA/10PCL | 32 | 67.6 | 41.2 | 177 | 303 | 298 | 336 | 457 | 55 | 155 | – | 309 | 347 |

| 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL | 27 | 72.5 | 44.2 | 175 | 300 | 288 | 339 | 459 | 53 | 152 | 49 | 296 | 342 |

Fig. 6 shows the mass loss of composites and pure PLA and PCL polymers up to 600°C. PLA is fully decomposed at a Te of 387°C, while PCL degradation has a residual mass of 1.5wt.%. The mass loss of PCL stabilizes from 480°C, stating that the Ar atmosphere employed for thermal analyses hinders the full decomposition of this polymer. Concerning composites, compositions containing 44vol.% Al2O3 with PLA and PLA/PCL matrices (44Al2O3-PLA and 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL) the residual inorganic mass was 69wt.% and 73wt.% (42vol.% and 45vol.%), respectively, while the weight ratio of the inorganic particles in the formulation of the composites was 44vol.% (72wt.%). TGA results indicate the high reliability in the granulation process with approximately an experimental deviation of 1.2vol.% (2wt.%) from the inorganic content formulation.

The difference in the solid content of 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL concerning the theoretical formulation could be related to the residual carbon from PCL decomposition in the Ar atmosphere. Although no residual mass of polymers is expected when thermal treatment is performed under an air environment. Urra et al. [29] reported that carbonaceous rest can be a sintering support for the green structure during debinding, helping to maintain the 3D shape during sample consolidation. The effect of thermal treatment atmosphere is studied in detail in “Sintering” section.

A clear difference between the degradation curves of composites containing PLA and PLA/PCL is observed. Pure PLA matrix composite shows a single-step degradation corresponding to the thermal degradation of PLA, denoted by a single slope at the TGA, and a single peak at the DTG. In contrast, composites containing PLA/PCL matrix show two well-defined slopes and peaks related to each polymer degradation. The first slope corresponds to the degradation of PLA, while the second corresponds to the degradation of PCL. This difference evidences that the polymers are immiscible and maintain their properties in the mixture.

The analysis of DTA leads to the characteristic temperatures of composites: the glass transition temperature (Tg), the melting temperature (Tm), and the degradation temperature (Td). The Tg of the PLA composites is similar to that of the pure PLA, while the incorporation of PCL distorts the measurement since the Tm of PCL is close to the Tg of PLA. Otherwise, all composites exhibit the Tm of PLA around 152°C, whatever the solid content or the PCL content. However, a significant shift of the degradation curves/mass loss towards lower temperatures is observed in the DTA-TGA curves due to the presence of inorganic particles in the thermoplastic matrix. The Td of composites reduces with respect to the pure polymers. For the pure PLA matrix composites, the Td reduces to 309°C for the 44vol.% and 265°C for the 48vol.% composites. The degradation of PLA/PCL matrix composites takes a longer time than that of the PLA matrix composites, exhibiting a double peak at 270°C and 329°C for 44Al2O3-PLA/10PCL and at 274°C and 337°C for 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL matrix. In these composites, the degradation peak of PLA is not affected by the PCL content, while the degradation peak of PCL displaces to higher temperatures for higher PCL content.

Table 3 also summarizes the characteristic temperatures of degradation derived from the thermal analysis. All composites evidence earlier initial degradation temperature (T0) and final degradation temperature (Te) than pure PLA or PCL polymers. Composites have a T0 around 170–175°C, while for PLA is 307°C, and for PCL is 337°C. No differences in T0 were observed due to solid load or matrix composition. However, Te seems to be influenced by these two factors. For pure PLA composites, Te is lower for sample 48Al2O3-PLA (323°C) than 44Al2O3-PLA (346°C). This suggests that the amount of inorganic particles in the composite accelerates the matrix degradation, which means, the degradation of the polymeric matrix takes place earlier and in a short time. Moreover, both composites with a PLA/PCL matrix and 44vol.% Al2O3 exhibit a reduction of Td by about 55°C compared to 44Al2O3-PLA. The presence of PCL at the formulation of granules enlarges more than 100°C the matrix decomposition, from 176°C to 346°C for 44Al2O3-PLA to 174°C to 452°C for 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL.

Table 4 summarizes relevant temperatures extracted from the DTA-TGA curves of filaments obtained by extruding granules in Table 1. The Al2O3 content of filaments is similar to that of the granules, evidencing the homogeneity of the mixture and the high strength of the interaction nanoparticle-thermoplastic matrix. Generally, the effects of the Al2O3 and PCL content over the characteristics temperatures for the filaments are similar to that observed for granules. Double degradation peaks appear when PCL is included in the formulation, and a decrease of the characteristic degradation temperatures, mainly of the PLA, is evidenced when the inorganic particle content increases. Characteristic temperatures measured for the filaments are some degrees higher than for the granules, in some cases up to 10–20°C. This effect can be attributed to forming stronger covalent bonds during extrusion (>152–155°C) among polymers PLA/PEI-Al2O3, and PCL/PEG/PEI-Al2O3.

Other determining factor to set the printing parameters are the viscosity and/or the flow behavior of the composites over the melting temperature. In order to scan the composite deformation behavior and the printing window temperature, oscillatory rheological studies were performed on melted granules and filaments. Dynamic melting rheology tests, shown in Fig. 7, provide information on the melted flow, the particle–polymer, and the particle–particle interaction under different shear rate conditions. The AS was carried out at a temperature over composites melting point (157°C) where storage (or elastic) modulus (G′) and loss (or viscous) modulus (G″) appear as a function of the deformation shear, under a fixed frequency of 1Hz. The evolution of G′ and G″ determines the melted behavior of composites. The linear viscoelastic region (LVR) extends to 0.1%, where composites start to deform as a plastic solid (G′>G″), to achieve the viscous regimen (G′<G″) at deformations >30%. Only the composite with 10% of PCL achieves the viscous flow (G′<G″) at 10%. Above the yield point, the internal structure of the composite is broken, and deformation becomes irreversible. In Fig. 7a, the higher is the Al2O3 content, the higher is the deformation, and hence the stress needed to achieve the viscous flow. Similarly occurs for the content of PCL at a given (44vol.%) inorganic content. The 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL melt granules achieve the highest elastic modulus of 4×106Pa at the LVR, while other composites maintain similar values (2×106Pa). In PLA composites, the flow point (G′=G″) takes place for a G′ of 3×103Pa (53%) for 48Al2O3-PLA and 1×104Pa (48%) for 44Al2O3-PLA. The stresses maintain in the range of 2–4×104Pa for 44Al2O3-PLA/PCL composites, while deformations are lower (11%) for the PLA/10PCL and 38% for the PLA/25PCL matrix.

(a) The evolution of the elastic and viscous modulus at the AS of the melted Al2O3-PLA and Al2O3-PLA/PCL granules. (b) The evolution of elastic modulus to compare deformation ratios among composites. (c) Results of the TS of 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL granules from 150 to 190°C at 0.1%, 1% and 2%. Melting rheology of 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL granules and filaments: (d) AS at 157°C and 1Hz of frequency; (e) TS from 150 to 190°C at 2% deformation and 1Hz of frequency; and (f) FS from 0.01 to 100Hz performed at 170°C and 2% deformation.

The plastic solid-like deformation prevails over most of the deformation range (0.3–10%), and in this region the elastic modulus decreases linearly for all composites. The magnitude of the plastic deformation also varies with the Al2O3 and/or the PCL content (see G′ evolution in Fig. 7b where G″ components were excluded to clarify). The higher slope is achieved for the 48Al2O3-PLA composite, which is due to the higher Al2O3 content in the pure PLA matrix. At a lower Al2O3 content, the plastic deformation ratio slightly decreases, from 1.07 for the 48Al2O3-PLA to the 0.99 for the 44Al2O3-PLA composite. Incorporating 10% of PCL also decreases the deformation ratio to 0.95, which maintains constant for 25% of PCL. The incorporation of 25vol.% PCL in the PLA matrix, in 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL composite, is enough to modify the flow of the melt composite, making it thicker, reducing the LVR, and enlarging and smoothing the plastic solid-like flow up to achieve a 38% deformation, from where the melt flows as a viscous liquid.

Fig. 7c shows the viscoelastic behavior of the 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL melt composite as a function of the temperature. The TS from melting temperature (Tm) up to 190°C were performed at a fixed frequency of 1Hz and fixed deformations overpassing the LVR, at 0.1%, 1%, and 2%, to determine the behavior of melt thermoplastic in the plastic deformation region. Melt composite behaves as a viscoelastic solid whatever the applied deformation, and the flow point is not reached under tested conditions. The G′ and G″ modulus keep constant in the evaluated temperature range, being G′>G″ in all cases. The melt composite deforms as a plastic solid-like, while the gap between G′ and G″ is narrower as the deformation increases. In fact, the melt composite tends to achieve a viscous flow when it is exposed to higher deformation, which is consistent with the behavior observed in AS. Finally, G″ almost match G′ values at 185°C for 2% deformation.

Plots in Fig. 7e–g compare the flowability of the melt composite, 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL, granules and filament shaped. At the AS (at 157°C and 1Hz, Fig. 7d), filaments and granules show a similar flow behavior. The plastic solid-like deformation prevails, being slower (lower deformation slope) the filament deformation, decreasing the deformation ratio from 0.95 to 0.76. This information agrees with the thermal and microstructural characterization of the filaments and the general idea of the formation of a stronger and more cohesive structure of the composite during the thermal extrusion. The TS shown in Fig. 7e (at 1Hz and 2% deformation) evidences the solid-like deformation (G′>G″) of the melt composite over the melting temperature (152°C) and the initial temperature of degradation (174–175°C) of the granules and filaments (Tables 3 and 4). At the FS performed at the limit conditions of flux, 170°C and 2% deformation, G′ and G″ are close for both materials, the viscosity being lower for 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL filaments. In both cases, composites achieve viscosity values around 105 and 106Pas for frequencies ranging 10–100Hz (62.8–628rad/s, considering the equivalence ω (rad/s)=2πf (Hz)), which can be considered suitable for printing, since commercial FFF printers reach, depending on the nozzle diameter, a shear rate of 100–1000s−1. Concluding that the viscosity values of 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL melt composites are suitable to be pulled through the extruder screw, flow through the nozzle, and build adequate 3D structures layer by layer using high-loaded feedstocks. These composites are printed in a plastic solid-like deformation regimen.

Printing of Al2O3 filamentsScaffolds and 3D dense parts, with different patterns and geometries were printed using 44Al2O3-PLA and 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL filaments. Details of printed samples and printing conditions are summarized in Fig. 8 (a, b, c, and the table at the inset). A picture of the scaffolds and the detail of the two linear patterns, printed at 90° (d) and 45° (e), and a gyroidal pattern (f), is also shown. Notice that with similar infill (40%), nozzle (0.5mm), flow rate (50%), and feed rate (40mm/s), lineal patterns lead to ∼500μm pores fully interconnected, while holes of gyroidal patterns are more intricate and bigger (∼1mm). Also, the accuracy of the surface finishing and the printed bars can be highlighted. Pictures of printed scaffolds demonstrate the elevated reliability and printing resolution of the 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL filaments. The exceptional printing precision of the 3D printed parts by FFF is attributed to the high content of Al2O3 nanoparticles and the solid-like plastic flow behavior of the melt filaments. This phenomenon arises from the layer-by-layer growth inherent in additive manufacturing technologies. As the layers form in gyroidal patterns and rotate relative to the previous layer, the pores become closed while maintaining their interconnectedness throughout the part's height.

The 3D models of the printed samples: (a) dense square with 100% infill and rectilinear pattern, (b) circular scaffolds with gyroid pattern, and (c) linear scaffold with rectilinear pattern at 45°. Dimensions and printing parameters employed for the printing of Al2O3 structures are included in the insert table. (d) Pictures of as-printed samples and details of their surface finishing, printing reliability, and resolution of scaffolds printed with (d) a rectilinear pattern printed at 90°, (e) a rectilinear pattern printed at 45°, and (f) a gyroid pattern.

The layer bond interface is an important parameter that provides structural integrity and mechanical properties to as-printed parts. A strong and well-formed bond interface ensures effective load transmission between layers, enhancing the overall mechanical performance of the printed part. Conversely, a weak or defective bond interface can lead to delamination, reduced strength, and also compromise the structural integrity. Layer bonding is more dramatic for sintered parts since the defects formed during shaping are maintained, even amplified in the final component during sample consolidation.

In FFF, the feedstock is printed under melt conditions, and then it solidifies while it bonds with the previous layer. Consequently, the layer adhesion depends on the ability to pass from a melt state to the solidification of the matrix. Previous results illustrate how the PCL and Al2O3 nanoparticles addition, as well as the thermal extrusion, alters the microstructure of the composite and its melt flowability. Several factors could hinder layer adhesion. In fact, the rheology of those melt composites (44Al2O3-PLA and 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL) demonstrates that they hardly achieve the viscous flux, and the high amount of nanoparticles could act as a physical barrier in the interface. Additionally, the process parameters such as printing temperature, extrusion rate, and layer height have a significant impact on the bond interface.

To evaluate the differences in layer adhesion between two thermoplastic matrices (PLA and PLA/PCL), the dense samples with 100% infill and a linear pattern were printed with a nozzle of 1mm in diameter. Fig. 9 shows the cross-section of 44Al2O3-PLA and 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL 3D printed parts and a scheme of the proposed mechanism to explain the evolution of the layer-by-layer deposition. In the 44Al2O3-PLA sample (Fig. 9b), printing layers can be clearly distinguished, while they are not visible for the as-printed 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL sample (Fig. 9c). This suggests that enhanced melt flowability with the PCL incorporation improves layer adhesion. The results discussed in “Granules and filament fabrication” section demonstrate that immiscible PCL and PLA polymers compatibilize through the incorporation of modified PEI-Al2O3 nanoparticles, leading to a uniform and homogeneous mixture (at the granules).

Moreover, polymers strengthen their microstructure by the formation of covalent bonds during thermal treatments, such as granules drying and filament extrusion. In this way, a homogeneous PCL/PLA mixture covers uniformly the PEI-Al2O3 nanoparticles (Fig. 4b), strengthening the particle-matrix interaction. However, the immiscibility of PLA and PCL polymers allows for maintaining their single properties when they are mixed, which means that two melt events are expected in PCL/PLA composites corresponding to each polymer (Table 4). For temperatures <60°C, the PCL melts, and hence, the PCL/PLA matrix partially melts at a lower temperature than the pure PLA matrix composite. In this way, well-dispersed melt PCL favors the layer adhesion observed in 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL printed parts, up to erase the interface between solid layers.

At the scheme in Fig. 9a, the PLA composites melt but hardly achieve the viscous flow, provoking the formation of defects at the layer interface. The high viscoelasticity of PLA melt composites also affects the mechanical response of melt filaments and granules to the shear rate. Stress provokes the formation of discontinuities in the particle-matrix adhesion, and those points/regions compromise the quality of filaments and green printed parts which favor crack propagation and delamination in further processing steps. This agrees with the stiff/brittle fracture of PLA composites, where alumina particles become exposed. The cross-section of the 44Al2O3-PLA filament in Fig. 4a is an example. The brittle fracture indicates a weaker interface if compared with PLA/PCL composites (Fig. 4b), since PCL fibers enhance flowability and the flexibility of the composite.

SinteringThe results of the DTA-TGA analyses of the 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL filaments described in “Granules and filament fabrication” section (Table 4) leads to total decomposition of the thermoplastic matrix at 600°C, evidencing the presence of a carbon residue (1.5%) coming from the partial elimination of the PCL in Ar atmosphere. To deeply study the effect of the atmosphere on sample consolidation dilatometric (DIL) analysis was performed in 100% infill printed and pre-sintered samples. Samples were debound using two different atmospheres: air and argon. The thermal cycle to pre-sinter the samples involves heating the pieces up to 800°C for 20min with heating and cooling rates of 1°C/min. For DIL samples were heated up to 1550°C with a heating rate of 5°C/min in air. Dilatometric curves and their derivate are shown in Fig. 10a.

(a) Dilatometric analysis performed in xy-and z-direction of dense 3D pieces of 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL pre-sintered up to 800°C under Ar and air atmosphere. (b) Cross-section of the sintered 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL piece after the dilatometric analysis under Ar flow showing the presence of black heart. (c) Thermal treatment of debinding and sintering proposed for the FFF of Al2O3 pieces.

The dilatometric curve of the air-debound sample is shifted to a lower temperature than the Ar-debound sample. Shrinkage starts around 1100°C and 1300°C for air- and Ar-treated samples, respectively. The shrinkage of the samples at these temperatures indicates that the diffusion processes are taking place, and the sintering between particles begins. Air-treated samples reached a shrinkage of 9.2% and 10.2% in the XY and Z axes, whereas Ar-treated samples got 9.4% and 6.4% in XY and Z, respectively. Moreover, it is worth noting the difference in shrinkage rate between treated samples, observed in the derivate shrinkage curves. Once shrinkage starts in the air-treated sample, shrinkage is progressive until the end of the test, while the Ar-treated sample exhibits a pronounced shrinkage, reaching a maximum shrinkage rate at 1450°C. None of the samples reached stable shrinkage values, indicating that the sintering process has not finished at the temperature of the study.

The delay of the onset temperature and the lower shrinkage behavior of Ar-treated samples denotes that the sintering process is more active and efficient for the sample pre-sintered in air. The thermal debinding determines the degradation and the reaction of the thermoplastic binders, as well as the degradation products with the atmosphere. Under Ar atmosphere, the inefficient thermal debinding results in a 1.5wt.% carbon residue from PCL that affects sintering. An inert atmosphere, such as Ar, avoids combustion from burning the polymeric matrix as CO2. The lack of oxygen during debinding leaves behind the carbon residue from the organic binder [30,31].

On the contrary, the debinding atmosphere containing oxygen favors polymer degradation by combustion/burning, with no residue. Therefore, it is expected that carbon residue after debinding of Ar-treated samples migrates through it and significantly inhibits the diffusion processes and the shrinkage with respect to air-treated samples [31]. Carbon residue of Ar-treated samples is identified by the presence of the “blackheart” phenomenon (Fig. 10b), which is associated with the incomplete elimination of organic components. Consequently, a one-step thermal cycle in air environment, shown in Fig. 3c, is proposed for filaments and as-printed 3D parts, with a debinding cycle including a heating rate of 1°C/min up to 600°C, and the nano-Al2O3 sintering with a heating rate of 3°C/min and a dwell of 2h at 1500°C.

Filament composites were sintered to validate them as feedstock for the FFF of 100% Al2O3 pieces. Fig. 11 shows the microstructure and a detail of the cross-section/fracture surface of the 44Al2O3-PLA (Fig. 11a and c) and 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL (Fig. 11b and d) sintered filaments, while Table 5 summarize the main characteristics of the sintered filaments.

Main characteristics of the sintered filaments.

| Sample | Relative density** (%) | Total porosity (%) | Open porosity (%) | Close porosity (%) | Shrinkage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∅ (%) | L (%) | |||||

| 44Al2O3-PLA | 86.0±0.1 | 17.6±0.5 | 3.6±0.5 | 14.0±0.1 | 17.4±0.1 | 22.3±0.6 |

| 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL | 98.1±0.7 | 3.3±0.6 | 1.4±0.6 | 1.9±0.7 | 23.2±0.2 | 20.0±0.4 |

After sintering, both filaments seem quite similar and dense at low magnification (insets in Fig. 11c and d). However, the relative density, measured by Archimedes method, reveals that the 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL filaments are denser than 44Al2O3-PLA filaments, reaching 98.1% and 86.0%, respectively. Regarding radial shrinkage, 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL components reach a diameter shrinkage of 23.2%, which is higher than the 17.4% shrinkage observed in 44Al2O3-PLA filaments. These results demonstrate that the presence of PCL, homogeneously distributed among Al2O3 nanoparticles and PLA, leads to a higher degree of material consolidation for 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL. Both, nanoparticles content and PCL incorporation, are critical parameters to achieve the sintering of dense pieces. The SEM images evidence clear microstructural differences between both binder systems. Sintered 44Al2O3-PLA filament presents sharper/angular grains, and higher in size than that observed in 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL filament, suggesting a chemical interaction of the nanoparticles with the melt matrix during the thermal treatment. In contrast, 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL filament presents more rounded grains with a grain size closer to the primary size of raw Al2O3 nanopowder (Fig. 4b). Printed scaffolds were one-step sintered at 1500°C under air atmosphere following the cycle indicated in Fig. 10c. Fig. 12 shows optical images of a scaffold printed with a linear pattern at 45° (table at the inset in Fig. 8), before (Fig. 12a) and after (Fig. 12b) sintering. In general, the scaffolds contracts homogeneously, maintaining the shape of the infill and the printing resolution. However, in a closer inspection, thickening of printed bars at the points of intersection with the lower bar is evident. The sintered scaffolds achieved a high densification (95.9%) considering the low solid inorganic load in the feedstock (44vol.%), the lower inorganic charge employed for sinterable filaments at the literature. At similar sintering conditions, Tosto et al. [21] reported relative density values of 95% for Al2O3 sample with 52vol.% and MIM-base binder. Scaffolds shrinkage is different depending of the printing direction, while XY shrinkage achieves 19%, it doubles, up to 40%, in the direction of printing (Z), which agrees with the trend observed in the dilatometric curve (Fig. 10). The shrinkage differences could be attributed to the raster width 3D scaffolds are not symmetric due to printing bars losing the round cylinder form flattening during printing, which slightly modifies the height/width ratio. In general, it is considered that the width of the raster in FFF is around 1.2–1.5 times the diameter of the nozzle tip [32]. Based on the higher shrinkage observed in the z-direction, it can be assumed that the thinner the printing layer, the higher shrinkage and, therefore, better sintering behavior would be expected. These results highlight the importance of the printing resolution in the sintering of ceramic components.

The results described throughout this work demonstrate the successful development of Al2O3 feedstocks suitable for both hopper and filament printers to fabricate 100% ceramic components. The work highlights the relevance of the organic binder formulation to improve the filament quality in terms of flexibility, particle dispersion, and homogeneity, which have a significant effect on the quality of 3D printed and sintered parts. The covalent bond formed during the thermal processing between the thermoplastic matrix and inorganic particles strengthens their microstructure, enhancing the particle–polymer interaction and layer-by-layer adhesion. The selection of the organic binder system determines the post-processing steps. The polymeric binder employed in this work is eco-friendly and widely employed in FFF technology, which is an advantage over other mineral oil derivative binder systems with higher environmental impact, such as that reported by Notzel et al. [33] containing LDPE and paraffin wax, and Vuksic et al. [18] consisting in a mixture of paraffin wax and ethylene vinyl acetate. Additionally, the feedstocks developed can be consolidated by a one-step thermal cycle which reduces the processing time and operating cost without compromising the sample integrity, avoiding the solvent debinding step used in the consolidation of similar feedstocks studied by Truxova et al. [22] that increases debinding time up to 24h and the total consolidation time up to 90h. Finally, relative density of the scaffold achieved in this work (96%) is close to the values reported for samples processed for DIW by Alvarez et al. [34] using a higher solid load of 75wt.% of Al2O3 and more severe sintering conditions 1550°C during 6h.

ConclusionsPrintable granules and filaments were successfully formulated and processed to print 100% Al2O3 3D parts. The optimized thermoplastic PLA/25PCL blend provides the printing of the Al2O3 composites and a fully thermal process for debinding and sintering, reducing time and costs composites were prepared following colloidal processing and solvent casting routes. Minimal deviation is observed in the inorganic content (1.2vol.%/2wt.%). After extrusion, 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL filaments are dense and flexible enough for spooling and printing.

Characteristics temperatures of filaments are slightly higher than granules (up to 10–20°C), evidencing the stronger covalent bonds between polymers, PLA/PEI-Al2O3 and PCL/PEG/PEI-Al2O3, created during extrusion (>152–155°C). Particle addition accelerates polymer matrix degradation, and PCL increases the matrix decomposition range by more than 100°C compared to pure PLA matrix.

Dynamic rheology shows that a plastic solid-like deformation prevails over the printing shear rate range. The higher the Al2O3 content, the higher the deformation ratio and the stresses needed to achieve the viscous region. The incorporation of 25vol.% PCL in the PLA matrix, for 44vol.% of Al2O3 content, is enough to modify the flow of the melt composite, making it thicker, reducing the LVR and enlarging and smoothing the plastic solid-like flow up to achieve a 38% deformation, from where the melt flow as a viscous liquid.

The colloidally developed feedstock provides an extraordinary printing resolution of the 3D parts printed by FFF, while the layer-by-layer adhesion and, debinding and sintering strongly depends on the PCL and PLA combination. Presence of PCL with a lower melting temperature favors the adhesion between layers of 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL parts, suppressing the interface between solid layers after sintering.

Density of 44Al2O3-PLA/25PCL filaments after sintering was 98.1%, with a radial shrinkage of 23.2%, whereas scaffolds reached 95.9% of density and shrinkage of 19% in XY-axes and 39.9% in the printing direction. The presence of PCL, homogeneously distributed among Al2O3 nanoparticles and PLA, also leads to a higher degree of material consolidation, so both, nanoparticles content and PCL incorporation, are critical parameters to achieve dense sintered pieces.

This work has been supported by the Spanish Government through the projects PID2022-137274NB-C31 and TED2021-129920B-C41. Dr. C. Chirico acknowledges the Juan de la Cierva Incorporacion, FJC2021-047247-I, funded by MCIN (AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and by the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR”, and P. Ortega-Columbran acknowledges the industrial doctorate, IND2022/IND-23603, funded by Comunidad de Madrid. Dr A. Ferrandez-Montero acknowledges the “Atracción de Talento” Comunidad de Madrid project 2022-T1/IND-23973.