Introducción: El objetivo de este trabajo fue evaluar si la atención médica que recibieron pacientes menores de 5 años con bronquiolitis aguda se realizó de acuerdo con lo que establecen las guías de manejo clínico de esta enfermedad.

Métodos: Se revisaron 197 expedientes de niños hospitalizados durante 2012 y 2013 para saber si se emplearon las recomendaciones de las guías: American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), Sector Salud, México (SS) y Guía Práctica Clínica Bronquiolitis, España (GPCBA).

Resultados: Se atendieron 197 niños por 49 pediatras. De las acciones recomendadas en las guías, en 110 niños se aspiraron secreciones (55.8%), a 105 se les administró oxígeno suplementario (53%) y 63 recibieron una solución hipertónica inhalada (31.9%). En cuanto a las acciones no recomendadas, en 166 de ellos se emplearon broncodilatadores inhalados (84%), a 143 se les dio esteroides inhalados (72%), a 110 se les indicó antibióticos (55.8%), en 76 se empleó humidificador (38%) y 52 recibieron esteroides sistémicos (26.3%). Cabe mencionar que los médicos con menos de 10 años de experiencia dieron a los niños más esteroides sistémicos.

Conclusiones: A pesar de la difusión de las guías de buena práctica clínica para el manejo de la bronquiolitis aguda, su adopción no ha sido completa.

Background: The aim of this study was to analyze the medical care of children<5 years of age with acute bronchiolitis in relation to the most relevant practices of evidence-based guidelines for bronchiolitis.

Methods: We reviewed the charts of 197 hospitalized infants with acute bronchiolitis during 2012 to 2013 to analyse whether the guideline recommendations were used according to: American Academic of Pediatritians (AAP), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), Sector Salud México (SS), and Guía Práctica Clínica Bronquiolitis, España (GPCBA).

Results: We evaluated 197 patients attended by 49 pediatricians. Of the recommended actions, in 110 patients (55.8%) aspirate secretions were indicated, 105 patients (53%) received supple-mental oxygen and 63 patients (31.9%) used inhaled hypertonic solution. Non-recommended actions were carried out in 166 patients (84%) who received inhaled bronchodilators, 143 patients (72%) who inhaled steroids, 110 patients (55.8%) who were prescribed antibiotics, 76 patients (38%) who had nebulization and 52 patients (26.3%) were administered systemic steroids. Physicians with<10 years of expertise prescribed more systemic steroids.

Conclusions: Despite the dissemination of good clinical practice guidelines for the management of acute bronchiolitis, its adoption has not been totally completed.

1. Introduction

Acute bronchiolitis in children is an infectious respiratory illness and is a common reason for consultations in first-and second-level care hospitals,1,2 especially during the winter.1,3 This disease is generally caused by the syncytial virus that causes inflammation and obstruction of small caliber airways and causes mild to severe respiratory difficulty.3 Generally, management is directed towards providing respiratory support while the inflammatory process is controlled.1,2

In recent years, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPG) have been developed in several countries to improve the treatment of these patients.2,4,5 These guidelines emphasize not recommending the use of antibiotics or systemic or inhaled steroids and the use of inhaled hypertonic solutions is recommended.6 On the other hand, use of bronchodilators is still recommended by some guidelines, but not more than two doses, and as a treatment test for children with bronchial overreactivity.7

In Mexico, health and social security institutions such as the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS), the Institute of Safety and Social Services of State Workers (ISSSTE), the Department of National Defense (SEDENA), Mexican Petroleum (PEMEX), the National System for Integral Development of the Family (DIF) and the Department of the Marines7 developed and disseminated management guidelines for acute bronchiolitis in children, which is available on the internet.2,4,5,8 The success of CPG is based on its distribution, especially when the medical staff adopts it such as in the report by Millat et al. of an investigation directed at the medical actions pre- and postadoption of the guidelines.8 The objective of this investigation was to review the medical care provided in a private hospital to children <5 years of age with acute bronchiolitis in order to determine if the treating physicians followed what is established by the CPG for children with this disease.

2. Methods

Included were children<5 years of age who were seen between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2013 with a diagnosis of acute bronchiolitis based on the clinical manifestations characterized by general malaise, fever, breathing difficulty and expiratory wheezes. Excluded from the study were those children with chronic pulmonary disease, cerebral palsy or any type of chest tumor.

Type of treatment was established by the responsible physician. For each child, the pertinent information was gathered: if treatment was inhaled or systemic, indication for oxygen therapy or aspiration of secretions in the upper airways, and days of hospital stay. Information was obtained from the pediatrician who treated the child as well as the years of professional practice in according to the date of the professional license. All information was kept confidential.

2.1. Selection of clinical practice guidelines

To evaluate the impact, the guidelines to be considered were first determined for their comparison. Those that were published in PubMed (2006-2014, MeSH; evidence-based guidelines AND acute bronchiolitis) were chosen and that met the criteria of being evidence based and not older than 10 years. In addition, the care guide for bronchiolitis from the health sector in Mexico was incorporated.7 From each guide the recommendations classified as A (strong evidence) and B (moderate evidence) were obtained about the treatment to consider an adequate clinical practice. The recommendations were grouped as those to carry out and those to avoid. The level of evidence of the recommendation was also obtained from the guides (A: based on randomized clinical trials with or without systematic reviews; B: based on cohort studies; C: based on case studies and controls; D: based on the opinion of experts).

2.2. Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized (sex, age, season, and year of care) according to simple frequencies and percentages. For each of the indications the frequency and percentage annotation were obtained. The percentages were compared by year of analysis (2012 vs. 2013) and years of pediatric experience of physicians (<10 years, 11-20 years and>20 years). For comparisons, χ2 test was used. Days of hospitalization were summarized in medians and interquartile ranges of the years of life, and comparison was done with Kruskal-Wallis test; p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. To establish adherence to the recommendations of each of the proposed guidelines is considered as “adherence” if 50% or more of the physicians met with the recommendation with their patients.

2.3. Ethical considerations

The project was reviewed and approved by the Research Committee of this hospital. Anonymity and confidentiality of data were maintained at all times as well as patient integrity. The project was financed by the authors.

3. Results

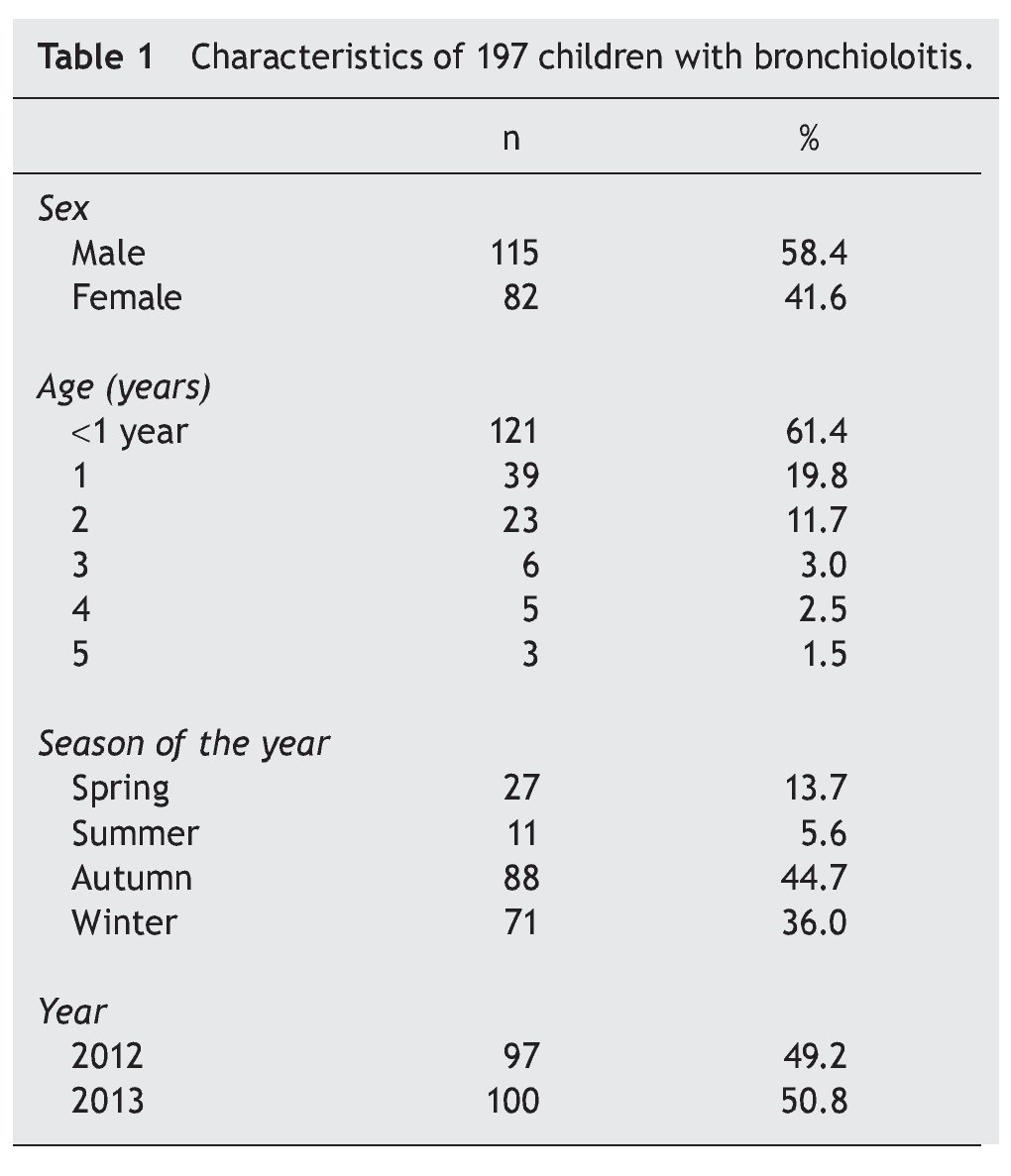

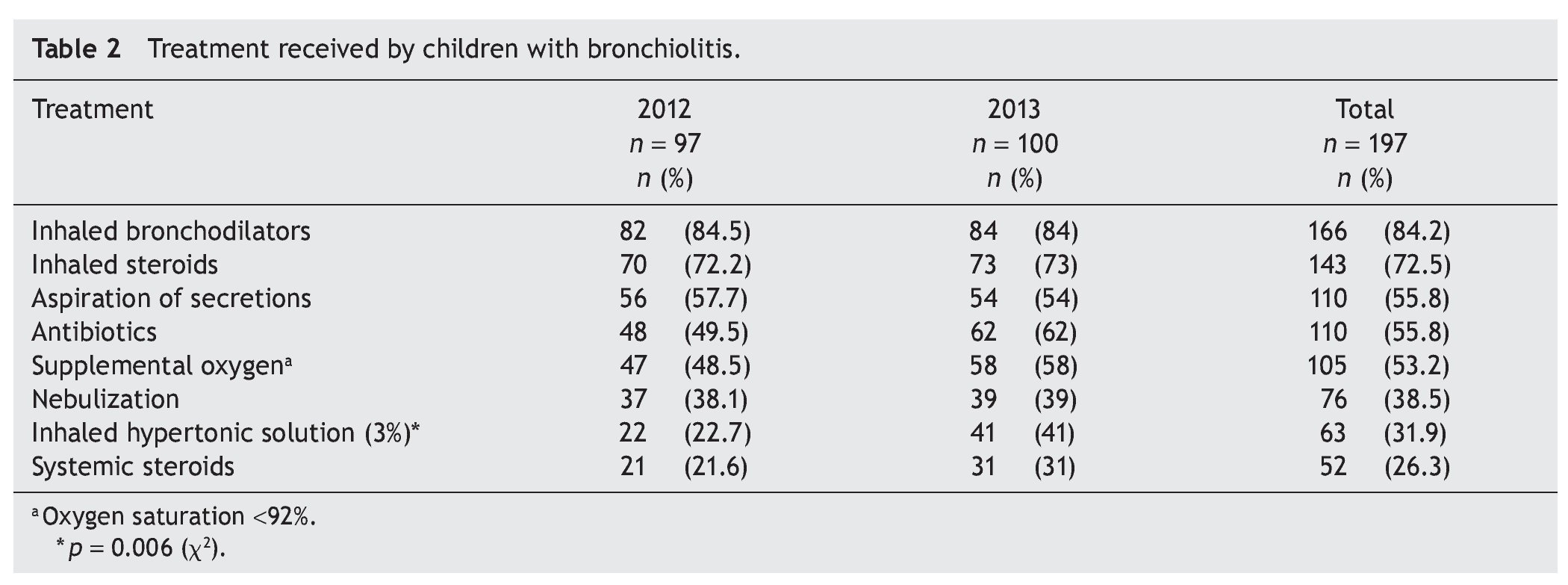

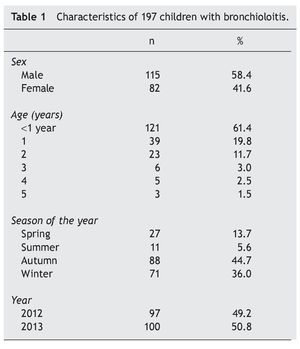

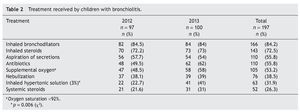

During the study period, 197 children with acute bronchiolitis were seen. Distribution by gender, age, season and year are summarized in Table 1. There was a slight male predominance and more than half were children<1 year of age. The majority of cases presented themselves in the fall and winter, and there were no significant differences according to year of analysis. Of the medical indications for children with bronchiolitis, use of inhaled bronchodilators was 84.2% followed by inhaled steroids (72.5%). In a little more than 50% of the children, aspiration of secretions was indicated (55.8%), use of supplemental oxygen (53.2%) and initiation of an antibiotic (55.8%). The use of 3% inhaled hypertonic solutions was only recommended in a third of the children (31.9%) and was more common for the year 2013 (with a statistically significant difference, p = 0.006). Finally, 26.3% (52/197) of the children received systemic steroids (Table 2).

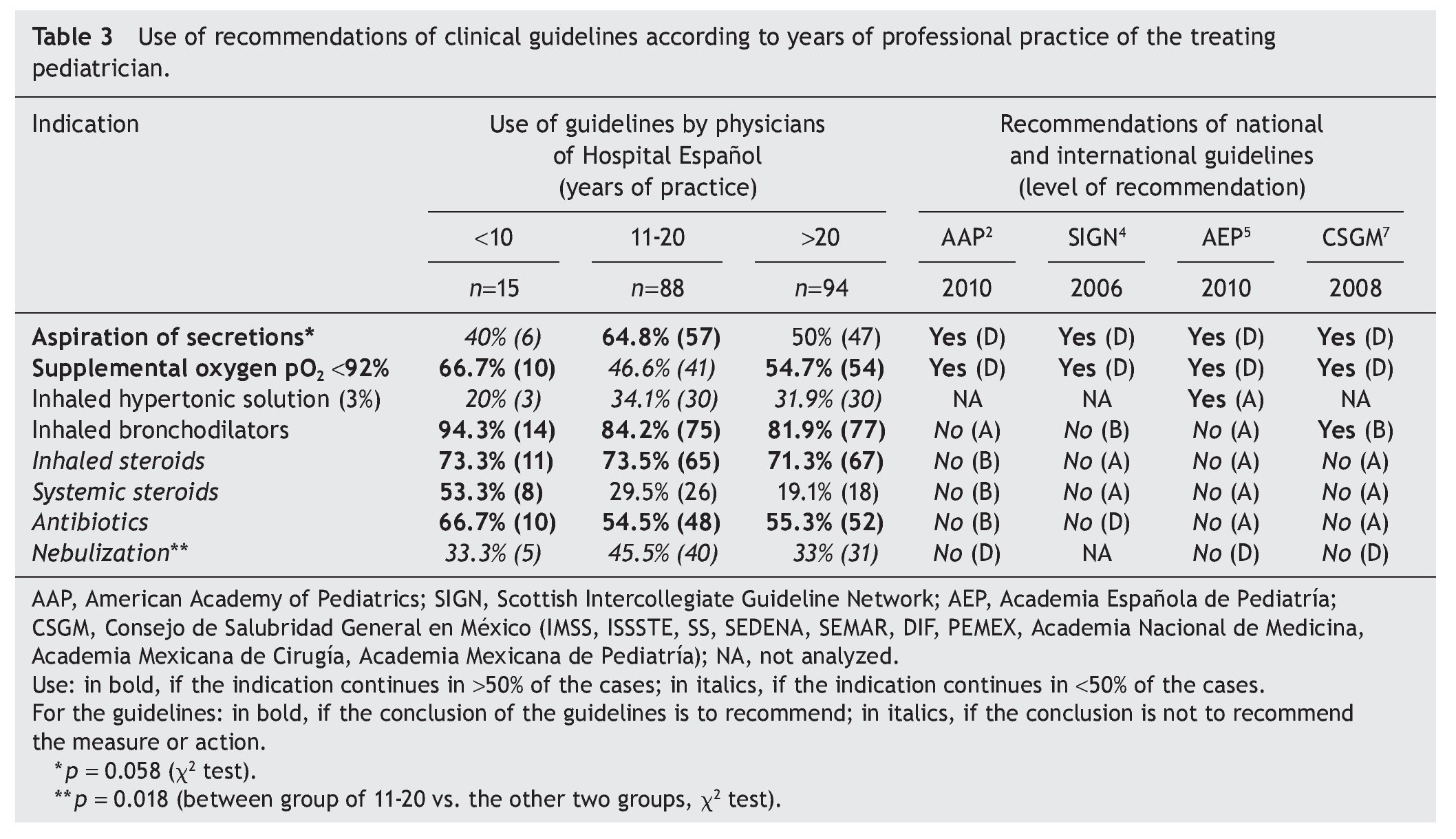

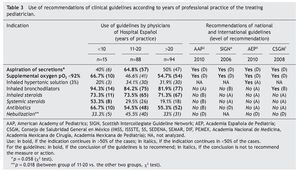

On analyzing the indications issued by pediatricians according to their years of experience (Table 3), few differences were seen among the groups. In particular, the group in practice >20 years indicated more measures or treatments according to the recommendations of the guidelines considered (aspiration of secretions, supplemental oxygen support with peripheral oxygen saturation when <92%, as well as not using a nebulizer). With regard to the non-recommended indications, the tendency to recommend inhaled steroids and the use of antibiotics was present in all groups, particularly the group with<10 years of experience who recommended the most systemic steroids.

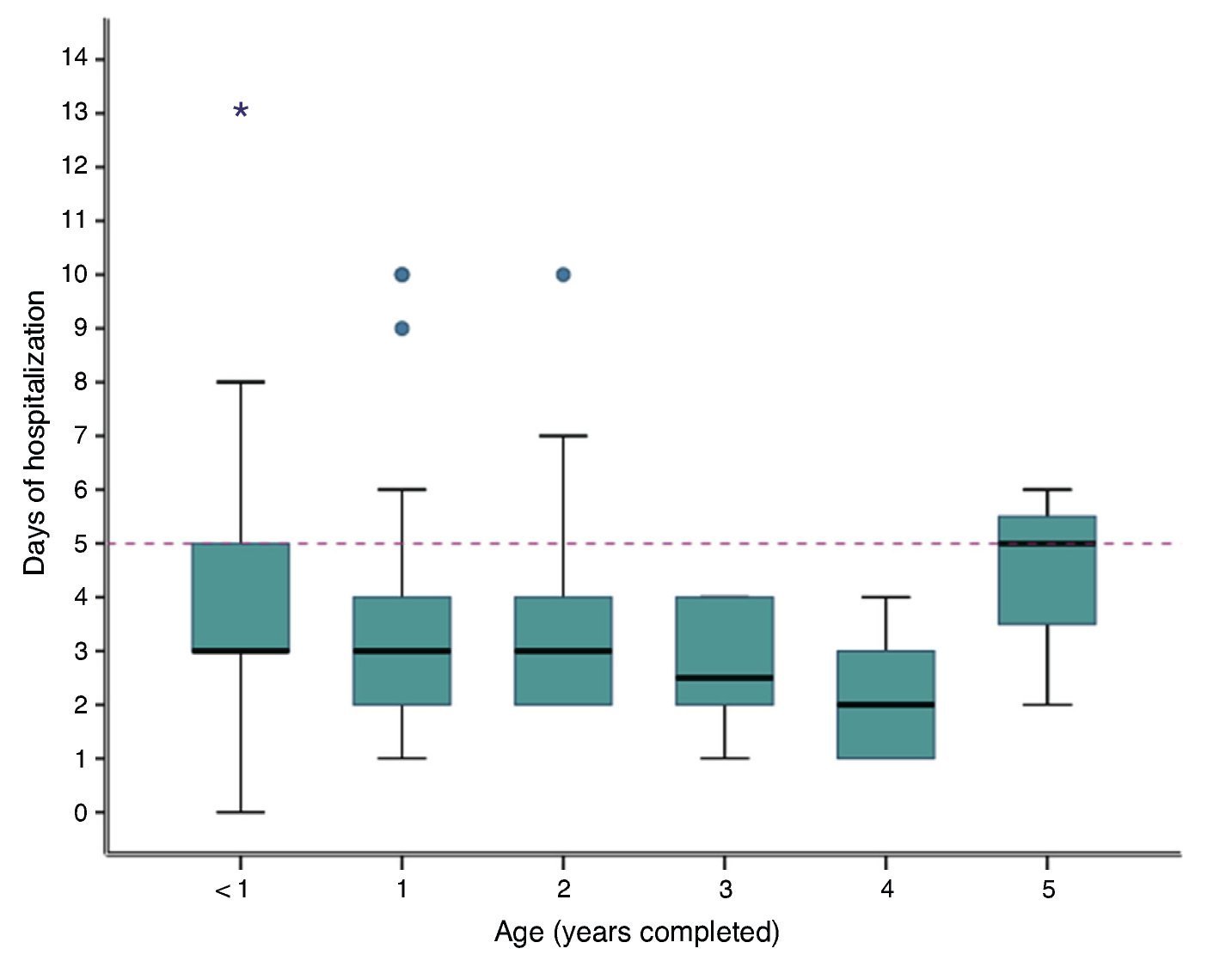

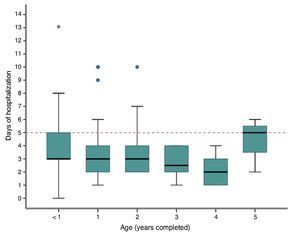

The recommendation to treat with inhaled hypertonic 3% solution was low in all groups (<35%). The use of bronchodilators alone recommended by the General Health Council of Mexico (CSGM) was met by all age groups. With regard to days of hospitalization there were no differences with respect to the age of the child (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Distribution of days of hospital stay according to age. Table interquartile range 1-3, median horizontal line. Kruskal-Wallis p = 0.07.

4. Discussion

Evidence-based good practice CPGs were designed with the purpose of standardizing clinical management in order for children to receive good care using scientifically supported measures. In this investigation, the majority of the children received adequate care as support measures were adopted (aspiration of secretions, administering oxygen under hypoxemic conditions, not recommending use of nebulizers) which, despite not being recommended, are recommended in all the guidelines as a correct practice (level D recommendation).2,4,5,7

Contrary to the usual recommendations, it appears that the guidelines analyzed do not agree with the indication of medication use.2,4,5,7 In the first place, use of inhaled hypertonic solutions is not pervasive. This therapeutic modality, although with few years of scientific support, has been demonstrated to have a high efficacy.5,6 Perhaps because of this, some systematic reviews have allowed its use to be incorporated in the guidelines.9 However, the CSGM guideline,7 the North American AAP2 and the British SIGN4 do not yet incorporate this therapy. In this study it was seen that the low adherence to this therapy by some physicians has increased in the past year, although without it being adopted as a common measure.

According to some guidelines, use of inhaled bronchodilators is considered as an initial option for therapeutic test for children with bronchial hyperactivity.7 However, this option should be used in only one dose. In three of the guidelines considered, the recommendation is not to use it (with a level of evidence “A and B”). It is possible that the high frequency of indication by physicians was due to the adherence to the national guidelines and its use being established during >20 years. In fact, it was observed that there were no differences in its indication with respect to years of experience.

The results alert us to the necessity of modifying actions that lack scientific support: use of steroids (in its different presentations) and antibiotics. These therapies have demonstrated their ineffectiveness in symptom improvement or shortening of the evolution of bronchiolitis and, in fact, have been associated with complications.6,7 The

four guidelines analyzed do not recommend their use with a high level of evidence “A” and “B”.2,4,5,7 In a study prior to the introduction of the AAP guidelines, it was observed that when physicians were trained, a significant reduction in the use of antibiotics was achieved, although at the end of the study they were still being prescribed in <30% of the cases.8 In this study the recommendation was carried out in 55.8% of the cases, a percentage similar to the work mentioned previously but prior to the introduction of the guidelines.

With respect to the inhaled steroids there was a high frequency of recommendations observed (72.5%) and without differences related to years of physician experience. These medications have demonstrated their effectiveness in chronic inflammatory problems and those of allergic origin, but not in acute infections such as bronchiolitis.2 For this reason, the guidelines analyzed do not recommend its use. With regard to the use of systemic steroids it was notable that the highest recommendation was from physicians with less experience who would be expected to be more up-to-date on the guidelines.

The main strength of this study is the observation of physicians’ behavior in a center with greater freedom of action. This allows us to better determine how physicians act based on their knowledge and convictions and not before the pressure of pre-established protocols. Also, due to being a private hospital, there are no economic restrictions on the medications requested.

The study was blind to the management of the patients as the physicians did not know that their recommendations would be analyzed. On the contrary, there are different limitations for the generalization of these results. The first is the representativeness of the physicians. Being a single hospital the behaviors observed may differ from other centers. Second, the guidelines considered are those of greater availability or with better academic recognition. It was considered important to take into account the CSGM because it is the guideline recommended in our country.

In conclusion, despite the dissemination of good clinical practice guidelines for the management of acute bronchiolitis, their adoption has not been complete. In general, physicians take into account the recommendations of respiratory support, but there was still indication of actions with little or no benefit or with potential harm to patients.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest of any nature.

Received 5 August 2014;

accepted 31 August 2014

* Corresponding author.

E-mails:drmariorendon@gmail.com, mario.rendon@imss.gob.mx (M.E. Rendón Macías).