Patients who experience both vertigo and nystagmus in the Dix-Hallpike test (DHT) are diagnosed with objective benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). This test provokes only vertigo in between 11% and 48% of patients, who are diagnosed with subjective BPPV. Detection of nystagmus has important diagnostic and prognostic implications. To compare the characteristics of patients diagnosed with objective and subjective BPPV in primary care. Cross-sectional descriptive study. Two urban primary care centers. Adults (≥18 years) diagnosed with objective or subjective BPPV between November 2012 and January 2015. DHT results (vertigo or vertigo plus nystagmus; dependent variable: nistagmus as response to DHT), age, sex, time since onset, previous vertigo episodes, self-reported vertigo severity (Likert scale, 0–10), comorbidities (recent viral infection, traumatic brain injury, headache, anxiety/depression, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, altered thyroid function, osteoporosis, cervical spondylosis, neck pain). In total, 134 patients (76.1% women) with a mean age of 52 years were included; 59.71% had subjective BPPV. Objective BPPV was significantly associated with hypertension, antihypertensive therapy, and cervical spondylosis in the bivariate analysis and with cervical spondylosis (OR=3.94, p=0.021) and antihypertensive therapy (OR 3.02, p=0.028) in the multivariate analysis. Patients with subjective BPPV were more likely to be taking benzodiazepines [OR 0.24, p=0.023]. The prevalence of subjective BPPV was higher than expected. Cervical spondylosis and hypertensive therapy were associated with objective BPPV, while benzodiazepines were associated with subjective BPPV.

A los pacientes que experimentan tanto vértigo como nistagmo en la prueba de Dix-Hallpike (DHT) se les diagnostica vértigo posicional paroxístico benigno objetivo (VPPB). Esta prueba provoca solamente vértigo entre el 11 y el 48% de los pacientes a los que se les diagnostica VPPB subjetivo. La detección de nistagmo tiene importantes implicaciones diagnósticas y pronósticas. Comparar las características de los pacientes diagnosticados de VPPB objetivo y subjetivo en Atención Primaria. Estudio descriptivo transversal. Ubicación: 2 centros urbanos de Atención Primaria. Participantes: adultos (≥18 años) diagnosticados de VPPB objetivo o subjetivo entre noviembre del 2012 y enero del 2015. Resultados de la DHT (vértigo o vértigo más nistagmo; variable dependiente: nistagmo como respuesta a la DHT), edad, sexo, tiempo desde el inicio, episodios de vértigo previos, gravedad del vértigo autoinformada (escala Likert, 0-10), comorbilidades (infección viral reciente, lesión cerebral traumática, dolor de cabeza, ansiedad/depresión, hipertensión, diabetes mellitus, dislipidemia, enfermedad cardiovascular, función tiroidea alterada, osteoporosis, espondilosis cervical, cervicalgia). Se incluyó a 134 pacientes (76,1% mujeres) con una edad media de 52 años. El 59,71% presentaba VPPB subjetivo. El VPPB objetivo se asoció significativamente con hipertensión, tratamiento antihipertensivo y espondilosis cervical en el análisis bivariado y con espondilosis cervical (OR=3,94, p=0,021) y tratamiento antihipertensivo (OR=3,02, p=0,028) en el análisis multivariado. Los pacientes con VPPB subjetivo tenían más probabilidades de estar tomando benzodiacepinas (OR=0,24, p=0,023). La prevalencia de VPPB subjetivo fue superior a la esperada. La espondilosis cervical y la terapia hipertensiva se asociaron con VPPB objetivo, mientras que las benzodiacepinas se asociaron con VPPB subjetivo.

Vertigo is a common complaint that places a considerable burden on primary care services.1 Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) accounts for between 17% and 42%of all cases, with an annual incidence of between 10.7 and 140 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.2,3 BPPV is characterized by a short-lived rotating sensation induced by changes in head position. The posterior canal is the main canal affected (60% to 90% of cases).4 Posterior canal BPPV can be diagnosed in primary care with a targeted history, a basic physical examination, and administration of the Dix-Hallpike (DHT) test. This test is considered positive when it triggers both symptoms (vertigo) and nystagmus. Thediagnosis in this case is objective BPPV.5 The test may also be considered positive when it triggers vertigo only. In this case, the patient is diagnosed with subjective BPPV.6,7 Subjective BPPV is very common and accounts for between 11.5%8 and 48%9 of all cases of BPPV. One possible explanation for the absence of nystagmus is that the dislodged otolithic particles in the posterior semicircular canal may be sufficient to cause vertigo but not nystagmus.7 It is also possible that mild nystagmus may go unnoticed if specialized equipment, such as videonystagmography systems or Frenzel goggles, is not used.6 The likelihood of a false-negative result is therefore greater in primary care, where between 60% and 80% of patients with BPPV are seen.10 In a randomized clinical trial analyzing the effectiveness of the Epley maneuver in the treatment of posterior canal BPPV in primary care, our group found that this maneuver was only effective in patients who had both vertigo and nystagmus at baseline (objective BPPV).11 Detection of nystagmus therefore has important diagnostic and prognostic implications and studies are needed to investigate factors associated with thiscondition.12

The aim of this study was to analyze factors associated with the presence or absence of nystagmus in the DHT in primary care patients with posterior canal BPPV.

MethodStudy designDescriptive, cross-sectional study based on the basal visit of a clinical trial with the objective to demonstrate the effectiveness of the Epley maneuver to treat PC-BPPV in primary care. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01969513.13

SettingTwo primary care centers with 26 general practitioners serving an approximate population of 38,305 people in L’Hospitalet de Llobregat (Barcelona, Spain).

Inclusion criteriaPatients aged 18 years or older with posterior canal BPPV and a positive DHT for vertigo only or for vertigo plus nystagmus. Patients who had neither vertigo nor nystagmus with DHT were excluded from the study.

Exclusion criteriaSuspected Menière's disease, labyrinthitis, vestibular neuronitis, pregnancy, breastfeeding, and contraindications for performance of the DHT or Epley maneuver or treatment with betahistine. Patients with findings suggestive of involvement of a semicircular canal other than the posterior canal or any other diagnosis, such as vertigo of central origin, were also excluded and referred to an ear, nose, and throat specialist. Nineteen of the patients were excluded following recruitment because they had findings consistent with vestibular migraine. Although this possibility was not contemplated in the initial protocol,13 vestibular migraine is very common and findings published after our study was designed have shown that this condition has overlapping symptoms with BPPV.14

Participant selectionConsecutive patients with symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV were recruited by GPs at the two participating primary care centers. The recruitment period was November 2012 to January 2015.

ProceduresThe recruiting team took a full history from the patients, performed a full physical examination, and revised their electronic health records. The baseline DHT was considered positive if it triggered vertigo and nystagmus (objective BPPV) or vertigo only (subjective BPPV) when performed on either the right or left side.

The following variables were recorded for all patients:

- •

Dependent variables: presence or absence of nystagmus in the DHT.

- •

Independent variables: age; sex; time since onset of symptoms, self-reported severity of vertigo symptoms on a Likert scale of 0–10, where 0 corresponds to no symptoms and 10 to the worst imaginable symptoms); history of recent viral infection, traumatic brain injury, headache, anxiety/depression, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, altered thyroid function, osteoporosis, cervicalspondylosis, neck pain; pharmacological treatment of vertigo (betahistine as monotherapy or combined therapy or treatment with dimenhydrinate, sulpiride, or thiethylperazine); other treatments (anti-depressants, benzodiazepines, and antihypertensives).

The sample size was calculated based on outcomes not presented in this paper, as the original trial was designed to determine the effectiveness of the Epley maneuver in the treatment of posterior canal BPPV in primary care. There were 66 patients in the intervention group (treated with the Epley maneuver and betahistine) and 68 in the control group (treated with a sham maneuver and betahistine).

Results are expressed as median and interquartile range for numerical variables and as absolute and relative frequencies for binary (indicator) variables and categorical variables (for each category). Results are presented for the overall sample and for the subsets of patients with subjective and objective BPPV. To test for significant differences for each of the study variables between patients with subjective and objective BPPV, we performed the Mann–Whitney U test for numerical variables and the Fisher exact test for categorical variables. A multivariate logistic regression model was built to explore factors associated with the presence of nystagmus. The explanatory variables included in the initial model were age, sex, time since onset of symptoms, number of previous episodes consistent with BPPV, self-reported severity of symptoms, history of a recent viral infection, traumatic brain injury, headache, anxiety/depression, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, altered thyroid function, osteoporosis, cervical spondylosis, neck pain, pharmacologic treatment of vertigo symptoms, and treatment with benzodiazepines, anti-depressants, and antihypertensives. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to select the best fit-model. This process involved excluding the different variables in a step-wise fashion and choosing the model with the smallest AIC, i.e., an AIC that was not reduced further by the exclusion of additional variables. The selected model was retested, again using the AIC, to see if reintroduction of any of the variables reduced the AIC further. We did not test for the effect of interactions between variables.

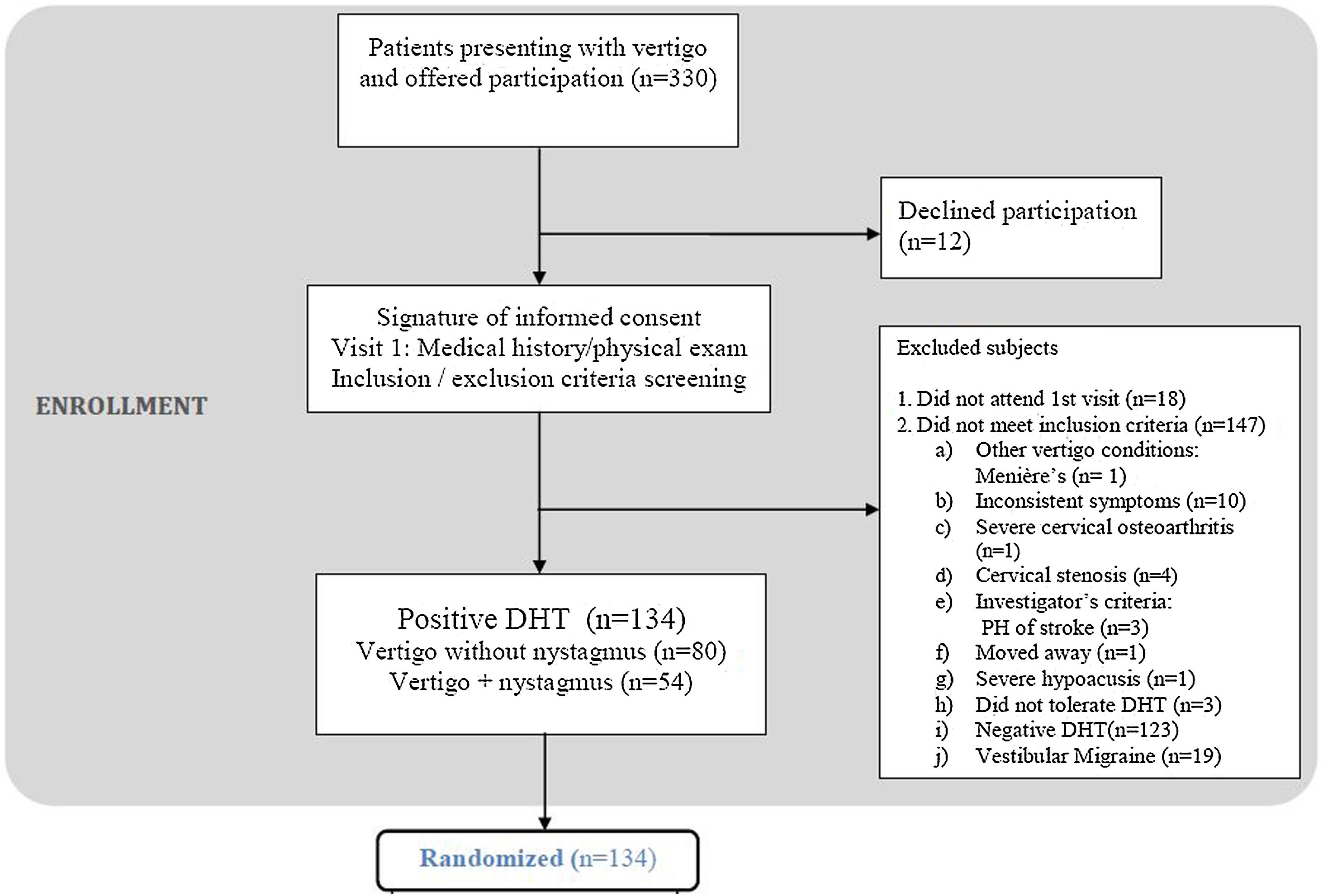

ResultsFig. 1 shows study flowchart.

We included 134 patients (76.1% women) with a median age of 52 years (interquartile range [IQR], 38.2–68.0 years). According to the baseline DHT, 59.7% of the patients had subjective BPPV and 40.3% had objective BPPV (Table 1).

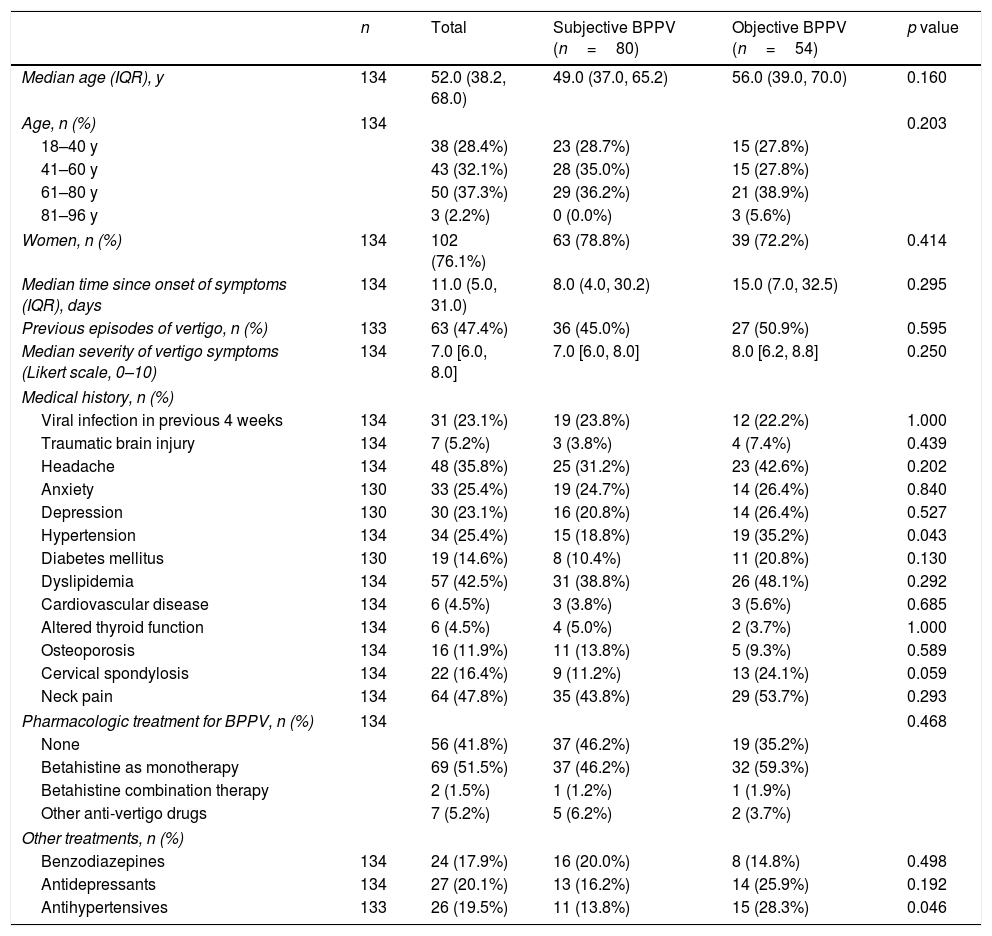

Patient characteristics for the total group and by subgroups of patients with subjective BPPV (vertigo only) and objective BPPV (vertigo and nystagmus) in the Dix-Hallpike text.

| n | Total | Subjective BPPV (n=80) | Objective BPPV (n=54) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR), y | 134 | 52.0 (38.2, 68.0) | 49.0 (37.0, 65.2) | 56.0 (39.0, 70.0) | 0.160 |

| Age, n (%) | 134 | 0.203 | |||

| 18–40 y | 38 (28.4%) | 23 (28.7%) | 15 (27.8%) | ||

| 41–60 y | 43 (32.1%) | 28 (35.0%) | 15 (27.8%) | ||

| 61–80 y | 50 (37.3%) | 29 (36.2%) | 21 (38.9%) | ||

| 81–96 y | 3 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.6%) | ||

| Women, n (%) | 134 | 102 (76.1%) | 63 (78.8%) | 39 (72.2%) | 0.414 |

| Median time since onset of symptoms (IQR), days | 134 | 11.0 (5.0, 31.0) | 8.0 (4.0, 30.2) | 15.0 (7.0, 32.5) | 0.295 |

| Previous episodes of vertigo, n (%) | 133 | 63 (47.4%) | 36 (45.0%) | 27 (50.9%) | 0.595 |

| Median severity of vertigo symptoms (Likert scale, 0–10) | 134 | 7.0 [6.0, 8.0] | 7.0 [6.0, 8.0] | 8.0 [6.2, 8.8] | 0.250 |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||||

| Viral infection in previous 4 weeks | 134 | 31 (23.1%) | 19 (23.8%) | 12 (22.2%) | 1.000 |

| Traumatic brain injury | 134 | 7 (5.2%) | 3 (3.8%) | 4 (7.4%) | 0.439 |

| Headache | 134 | 48 (35.8%) | 25 (31.2%) | 23 (42.6%) | 0.202 |

| Anxiety | 130 | 33 (25.4%) | 19 (24.7%) | 14 (26.4%) | 0.840 |

| Depression | 130 | 30 (23.1%) | 16 (20.8%) | 14 (26.4%) | 0.527 |

| Hypertension | 134 | 34 (25.4%) | 15 (18.8%) | 19 (35.2%) | 0.043 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 130 | 19 (14.6%) | 8 (10.4%) | 11 (20.8%) | 0.130 |

| Dyslipidemia | 134 | 57 (42.5%) | 31 (38.8%) | 26 (48.1%) | 0.292 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 134 | 6 (4.5%) | 3 (3.8%) | 3 (5.6%) | 0.685 |

| Altered thyroid function | 134 | 6 (4.5%) | 4 (5.0%) | 2 (3.7%) | 1.000 |

| Osteoporosis | 134 | 16 (11.9%) | 11 (13.8%) | 5 (9.3%) | 0.589 |

| Cervical spondylosis | 134 | 22 (16.4%) | 9 (11.2%) | 13 (24.1%) | 0.059 |

| Neck pain | 134 | 64 (47.8%) | 35 (43.8%) | 29 (53.7%) | 0.293 |

| Pharmacologic treatment for BPPV, n (%) | 134 | 0.468 | |||

| None | 56 (41.8%) | 37 (46.2%) | 19 (35.2%) | ||

| Betahistine as monotherapy | 69 (51.5%) | 37 (46.2%) | 32 (59.3%) | ||

| Betahistine combination therapy | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (1.9%) | ||

| Other anti-vertigo drugs | 7 (5.2%) | 5 (6.2%) | 2 (3.7%) | ||

| Other treatments, n (%) | |||||

| Benzodiazepines | 134 | 24 (17.9%) | 16 (20.0%) | 8 (14.8%) | 0.498 |

| Antidepressants | 134 | 27 (20.1%) | 13 (16.2%) | 14 (25.9%) | 0.192 |

| Antihypertensives | 133 | 26 (19.5%) | 11 (13.8%) | 15 (28.3%) | 0.046 |

Abbreviations: BPPV: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; IQR: interquartile range.

Patients with objective BPPV were more likely to have a history of hypertension (p=0.043) or to be on treatment with antihypertensives (p=0.046). We also detected a tendency toward a history of cervical spondylosis (p=0.059). No significant differences were found between the groups for any of the other variables.

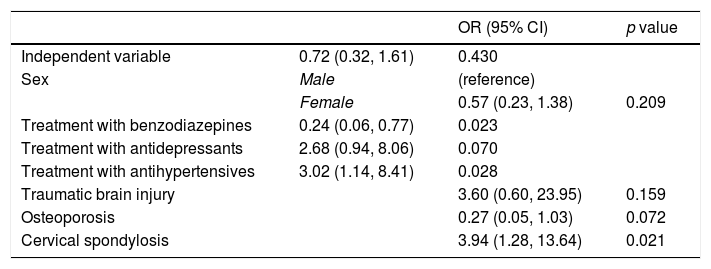

In the multivariate analysis (Table 2), patients with cervical spondylosis were more likely to have objective BPPV (odds ratio [OR]=3.94; 95% CI: 1.28–13.64; p=0.021) and so were those receiving antihypertensives (OR=3.02; 95% CI=1.14–8.41; p=0.028). Patients on benzodiazepines, by contrast, were more likely to present subjective BPPV (OR, 0.24; 0.06–0.77; p=0.023).

Multivariate regression analysis of predictors of nystagmus (without consideration of interactions).

| OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | 0.72 (0.32, 1.61) | 0.430 | |

| Sex | Male | (reference) | |

| Female | 0.57 (0.23, 1.38) | 0.209 | |

| Treatment with benzodiazepines | 0.24 (0.06, 0.77) | 0.023 | |

| Treatment with antidepressants | 2.68 (0.94, 8.06) | 0.070 | |

| Treatment with antihypertensives | 3.02 (1.14, 8.41) | 0.028 | |

| Traumatic brain injury | 3.60 (0.60, 23.95) | 0.159 | |

| Osteoporosis | 0.27 (0.05, 1.03) | 0.072 | |

| Cervical spondylosis | 3.94 (1.28, 13.64) | 0.021 |

Best-fit model according to the Akaike Information Criterion. The initial model included age, sex, time since onset of symptions, number of previous vertigo episodes, self-rated vertigo severity, recent viral infection, traumatic brain injury, headache, anxiety/depression, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, altered thyroid function, osteoporosis, cervical spondylosis, neck pain, pharmacological treatment of vertigo symptoms, and treatment with benzodiazepines, anti-depressants, and antihypertensives.

A high proportion of the primary care patients in our series (59.7%) had subjective BPPV. Cervical spondylosis (OR=3.94) and antihypertensive therapy (OR=3.02) were significantly associated with objective BPPV, while treatment with benzodiazepines was significantly associated with subjective BPPV (OR=0.24).

The DHT is considered the gold standard for diagnosing posterior canal BPPV, but the reliability of the diagnosis is strengthened when both vertigo and nystagmus areobserved.11,15 In a study by Balatsouras,5 63 patients had an initial diagnosis of subjective BPPV based on physical examination findings. However, additional testing with videonystagmography on the morning after recruitment showed that 21 of these patients actually had mild nystagmus that was not visible to the naked eye. Accordingly, 33% of these patients were rediagnosed with objective BPPV. An additional 11 patients were diagnosed with another condition and seven were left undiagnosed. Repositioning maneuvers were almost five times more effective in patients initially diagnosed with objective BPPV and were equally effective in patients with objective and subjective BPPV following the regrouping according to the results of the videonystagmography tests. Subjective BPPV therefore is a less reliable diagnosis than objective BPPV, particularly when based on the results of the DHT only (i.e., without additional tests such as videonystagmography).5

The multivariate analysis in our study showed an association between objective BPPV and cervical spondylosis. This link between BPPV and cervical spondylosis has been widely debated. While some authors question whether arthritis of the neck can cause BPPV,16 others claim that it can as it would reduce blood flow in this area,17 resulting in altered oculovestibular reflexes (on which nystagmus depends) and possibly vertigo.18

The results of our study also show that patients with objective BPPV are three times more likely than those with subjective BPPV to be on antihypertensive therapy. The association between BPPV and hypertension has been reported elsewhere and was first highlighted by Brevern et al.19 Other studies have shown that hypertension can increase BPPV recurrence 20and time to diagnosis.21 In our series, BPPV was associated with hypertension in the bivariate analysis and antihypertensive therapy in the multivariate analysis. Hypertensive patients under pharmacological treatment are probably more representative of the hypertensive population in general. In our series, treatment with benzodiazepines was significantly associated with subjective BBPV. In a prospective case-control study published in October 2018, no association was found between the use of anti-vertigo drugs (betahistine and sulpride) and the presence or absence of nystagmus.22 Our findings, by contrast, are consistent with those of Tan et al.,23 who found higher rates of vestibular suppressant medication use in patients who tested positive for vertigo on positional testing than in those who tested positive for both vertigo and nystagmus. When the patients were retested following withdrawal of medication (mostly benzodiazepines and antihistamines), 50% showed nystagmus (i.e., they had typical BPPV). As current guidelines do not recommend pharmacologic treatment of BPPV,24 anti-vertigo medication can be withdrawn in patients with an equivocal diagnosis and tests repeated within approximately a week.

LimitationsThe original study on which the results of this study are based was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the Epley maneuver in primary care, not to compare factors associated with the presence or absence of baseline nystagmus in patients with BPPV. Nonetheless, because BPPV is so common in primary care and because there is a dearth of literature on DHT responses in this setting, we believe that this substudy is important as it could help improve the diagnosis of this disease in primary care.

The high prevalence of subjective BPPV observed in our series is logical considering that GPs see more cases of mild BPPV (without nystagmus), have less experience in detecting these cases, and lack the equipment for doing so (e.g., Frenzel goggles and videonystagmography).

ConclusionBPPV is related in the present study with cervical spondylosis and arterial hypertension. Association of BPPV with cardiovascular risk factors makes recommendable monitoring these patients. Treatment with benzodiazepines can worsen the detection of nystagmus so it is never indicated in these patients. Future research should focus on determining whether interrupt sedatives medication before testing BPPV could improve nystagmus detection, providing more reliable diagnoses and better prognosis for patients.

- •

Posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most common type of vertigo seen in primary care settings.

- •

This condition can be adequately diagnosed and treated with the Dix-Hallpike (DH) test and canal repositioning maneuvers.

- •

The DHT provokes vertigo in the absence of observable nystagmus in a considerable proportion of cases (11%–48%).

- •

The prevalence of subjective BPPV detected in our primary care setting (59.71%) was higher than that observed in previous studies

- •

Patients with subjective BPPV are more likely to be taking benzodiazepines.

- •

Patients with objective BPPV (vertigo plus nystagmus in the DHT) are more likely to have cervical spondylosis and to be receiving antihypertensive therapy.

This project received a research grant from the Carlos III Institute of Health, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spain), awarded on the 2013 call under the Health Strategy Action 2013–2016, within the National Research Program oriented to Societal Challenges, within the Technical, Scientific and Innovation Research National Plan 2013–2016, with reference PI13/01396, co-funded with European Union ERDF funds. It was also funded by the cycle XIV (2013) research grant from the Spanish Primary Care Network (REAP) and a predoctoral grant from the Jordi Gol Institute for Research in Primary Care (IDIAP Jordi Gol) (2014/005E). IDIAP Jordi Gol also funded the translation of this article into English.

Conflicts of interestNone.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical and scientific assistance provided by the Primary Healthcare Research Unit of Costa de Ponent Primary Healthcare University Research Institute IDIAP-Jordi Gol. We also thank Neus Profitós and Celsa Fernández who were responsible for safeguarding the randomization sequence list. Finally, we thank all the participants of the Grupo de Estudio del Vértigo en Atención Primaria Florida: Estrella Rodero Pérez, Xavier Monteverde Curtó, Carles Rubio Ripollès, Noemí Moreno Farrés, Jean Carlos Gómez Nova, Johan Josué Villarreal Miñano, Diana Lizzeth Pacheco Erazo, Raquel Adroer Martori, Anna Aguilar Margalejo, Olga Lucia Arias Agudelo, Silvia Cañadas Crespo, Laura Illamola Martín, Marta Sarró Maluquer, Lluís Solsona Díaz, Rosa Sorando Alastruey (Equip d’Atenció Primària Florida Nord, Institut Català de la Salut, Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain). Austria Matos Méndez, Marta Bardina Santos (Equip d’Atenció Primària Florida Sud, Institut Català de la Salut, Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain).

Lead author: José Luis Ballvé Moreno.