Glaucoma, a leading cause of preventable blindness, significantly impacts patients' quality of life (QoL). The GQL-15 (1999) assesses functional disability due to glaucoma through 15 items across 4 domains. However, it has not been validated in Spanish. This study aimed to validate and update the GQL-15 for Spanish-speaking individuals.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study with individuals diagnosed with glaucoma at 2 ophthalmological referral centers in Cali-Colombia. Researchers translated the GQL-15 into Spanish and modified it by replacing the ‘reading newspaper’ item with ‘reading on a cellphone/mobile/smartphone’ to modernize the questionnaire (GQL-15 m). The GQL-15 m was tested for validity and reliability using Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficient, exploratory factor analysis, and criterion validity. Reproducibility was assessed through a 2-week test-retest analysis.

ResultsA total of 157 out of 468 eligible patients with glaucoma participated in the survey (33% response rate). The mean age was 67 ± 12 years (64%, women). The GQL-15 m showed a mean total score of 29.3 ± 7.31, suggesting good QoL. Internal consistency was high for both the GQL-15 (α = 0.97) and GQL-15 m (α = 0.96). Criterion validity was supported by significant correlations between the GQL-15 m scores and the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (NEI-VFQ 25), World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQoL-BREF), Glaucoma Symptom Scale (GSS), Glaucoma Utility Index (GUI), and visual acuity. Reproducibility was high, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.89.

ConclusionsThe GQL-15 m is a reliable and valid instrument for assessing QoL in Spanish-speaking individuals with glaucoma and has potential for broader application across various cultural contexts.

El glaucoma, una de las principales causas de ceguera prevenible, impacta significativamente la calidad de vida (CV) de los pacientes. El GQL-15 (1999) evalúa la discapacidad funcional debido al glaucoma a través de 15 ítems en cuatro dominios. No obstante, no ha sido validado en español. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo validar y actualizar el GQL-15 para individuos de habla hispana.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio transversal en individuos diagnosticados con glaucoma en dos centros de referencia oftalmológica en Cali, Colombia. Los investigadores tradujeron el GQL-15 al español y lo modificaron reemplazando el ítem "leer el periódico" por "leer en un celular/móvil/smartphone" para modernizar el cuestionario (GQL-15 m). Se probó la validez y fiabilidad del GQL-15 m utilizando el alfa de Cronbach (α), análisis factorial exploratorio y validez de criterio. La reproducibilidad se evaluó mediante un análisis de test-retest a las 2 semanas.

ResultadosDe 468 pacientes elegibles con glaucoma, 157 participaron en la encuesta (tasa de respuesta del 33%). La edad promedio fue de 67 ± 12 años, y el 64% eran mujeres. El GQL-15 m mostró una puntuación total promedio de 29.3 ± 7.31, lo que sugiere una buena CV. La consistencia interna fue alta tanto para el GQL-15 (α = 0.97) como para el GQL-15 m (α = 0.96). La validez de criterio se respaldó por correlaciones significativas entre las puntuaciones del GQL-15 m y el Cuestionario de Función Visual del Instituto Nacional del Ojo-25 (NEI-VFQ 25), el Cuestionario Breve de Calidad de Vida de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (WHOQoL-BREF), la Escala de Síntomas del Glaucoma (GSS), el Índice de Utilidad del Glaucoma (GUI) y la agudeza visual. La reproducibilidad fue alta, con un coeficiente de correlación intraclase (ICC) de 0.89.

ConclusionesEl GQL-15 m es un instrumento fiable y válido para evaluar la calidad de vida en individuos hispanohablantes con glaucoma y tiene potencial para una aplicación más amplia en diversos contextos culturales.

Glaucoma is a leading cause of preventable blindness worldwide.1,2 It is a progressive optic neuropathy characterized by alterations of the visual field associated with death of retinal ganglion cells, leading to blindness if untreated.3,4 As the population ages, the prevalence of glaucoma increases, with global cases projected to reach 111.8 million by 2040, including 12.86 million in Latin America and the Caribbean.5 Individuals experiencing vision impairment face heightened risks of injuries, social isolation, depression, and reduced quality of life (QoL).6,7

QoL is the sum of a range of objectively measurable living conditions including physical health, personal circumstances, social relationships, activities, functional abilities, and broader social and economic factors.8,9 Numerous QoL questionnaires have been developed for eye diseases, including glaucoma-specific instruments.10,11 Evidence indicates that patients with glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, cataracts, and uncorrected refractive errors tend to have lower QoL scores compared to those without these conditions.10,11 One of the most suitable questionnaires for assessing the impact of glaucoma on QoL, is the Glaucoma QoL Questionnaire (GQL-15) based on its quality, reliability, and reproducibility.12 The GQL-15, developed by Dr. Patricia Nelson in 1999, assesses vision-related difficulties in daily activities. It has been validated in Serbia and China, with Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients of 0.89 and 0.75−0.91, and intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.96 and 0.70, respectively.13,14 However, the ‘outdoor mobility’ domain had only one item (‘Adjusting to bright lights’), limiting the internal consistency analysis, and the scale is outdated, failing to account for the use of modern electronic media, such as cell phones. Updating the GQL-15 is crucial to accurately assess glaucoma patients' QoL and address key factors affecting their well-being.15

Given the cultural, social, and linguistic differences in Spanish-speaking populations, the results from existing studies cannot be directly applied to these groups. Therefore, this study aimed to validate the GQL-15 instrument for Spanish-speaking glaucoma patients, and to develop a modernized version replacing an item, resulting in the GQL-15 modified (GQL-15 m).

MethodologySettingCross-sectional study to validate and update the GQL-15 for Spanish speakers. Participants were recruited from two referral eye centers in Cali, Colombia. Ethical approval was obtained from Universidad del Valle (022-021), Hospital Universitario del Valle (055-2021), and the Ophthalmology Clinic of Cali (COC–CIC-055). All participants provided informed consent, and the study adhered to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

ParticipantsWe included patients diagnosed with primary open-angle, primary narrow-angle, or normal pressure glaucoma for ≥6 months, aged ≥18 years, who were seen between January 2019 and December 2021. Exclusion criteria comprised additional ocular pathologies (e.g., cataract, corneal opacity, macular degeneration), secondary glaucomas, other optic neuropathies, intraocular surgery within the past 6 months, high refractive errors, inability to answer questionnaires, and neurological or cognitive disorders affecting vision and QoL.

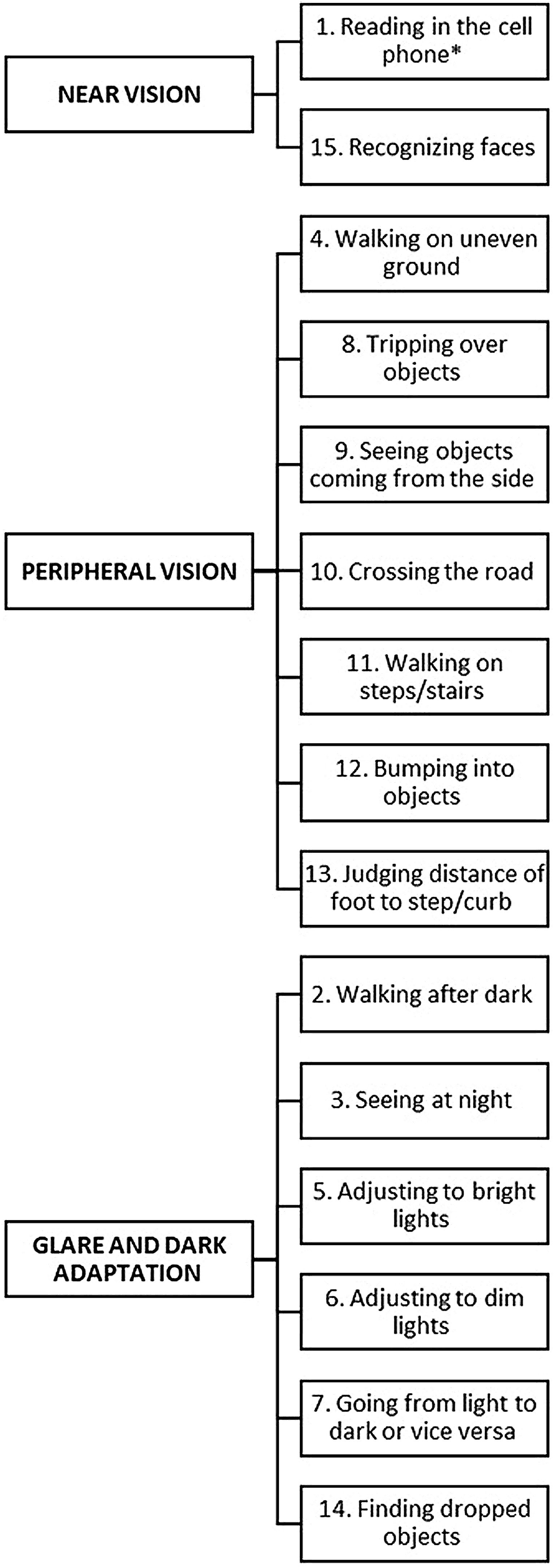

SurveyThe GQL-15 consists of 15 questions rated on a scale from 1 (no difficulty) to 5 (extreme difficulty), grouped into four domains/factors, 1. Central and near vision, 2. Peripheral vision, 3. Dark and glare adaptation, and 4. Outdoor mobility,16 with total scores ranging from 15 to 75. A score of 15 indicates no visual disability, while 75 reflects severe impairment across all visual tasks, measuring the functional disability caused by glaucoma in adults.17 The survey was administered by prehospital care personnel, over the phone, who were unaware of the patient’s diagnosis, duration of glaucoma, or its severity, to ensure unbiased data collection.

Translation, modernization, face and content validityWe obtained permission from Dr. Nelson to validate the survey. Two bilingual translators translated the questionnaire from English to Spanish and back-translated it to ensure semantic and conceptual equivalence.

To update the scale, the item ‘reading on a cellphone/mobile/smartphone’ replaced ‘read the newspaper’ to reflect changes in technology and reading habits. This revised version was named the GQL-15 modified (GQL-15 m), view Support File 1 for the Spanish questionnaire and Support File 2 for the English version.

The final questionnaire was administered to 10 individuals with similar characteristics to the study patients (adults with non-communicable diseases, aged ≥18 years) to assess face validity, ensuring clarity, simplicity, and relevance of the Spanish translation. Content validity was evaluated by three ophthalmologists, who reviewed and classified the questions into predefined domains.16

Sample size and sampling methodA total of 5,808 glaucoma patients were identified in both institutions. After excluding suspected and secondary glaucoma cases, 934 patients remained eligible. We employed systematic random sampling, stratified by healthcare center, to select participants. The patient list was randomly organized in an Excel file by institution, and every third individual was chosen for outreach.

Visual acuity data was extracted from medical records and converted into Logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution (LogMAR) scale for analysis. The questionnaire was conducted via telephone calls.

The sample size was based on a systematic review recommending 250–350 patients.18 A Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test was conducted to assess the suitability for factor analysis.

Reliability, construct validity, and criterion validityReliability of each question and the entire questionnaire was assessed using α. This analysis considered item covariances and item correlations, ensuring the coherence of items and their measurement of the same underlying construct. Additionally, a subscale analysis was conducted for each domain.

A Scree plot was used to determine the number of factors to retain for factor analysis. Construct validity was then assessed through factorial analysis with main axis and oblique rotation to identify underlying factors explaining the variance in the data. Internal consistency of each factor was measured using α, and communalities were used to assess the proportion of variance in each item explained by the factors.

Criterion validity was assessed by calculating Spearman’s correlation coefficients between the GQL-15 m and the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (NEI-VFQ 25), the World Health Organization QoL-BREF (WHOQoL-BREF), the Glaucoma Symptom Scale (GSS), and the Glaucoma Utility Index (GUI) to validate its ability to measure glaucoma-specific QoL. Additional correlations with age, sex, socioeconomic status, and visual acuity were explored.

ReproducibilityReproducibility was evaluated by applying the questionnaire twice in the same population, with a time lapse of 2 weeks between the application of the survey (test-retest reliability) and comparing the responses with the intraclass correlation test.19

ResultsTranslation and face validityThe translation process required no major changes, as the literal English-to-Spanish translation was adequate for most items. No further adjustments were needed after presenting the questionnaire during the face validity assessment.

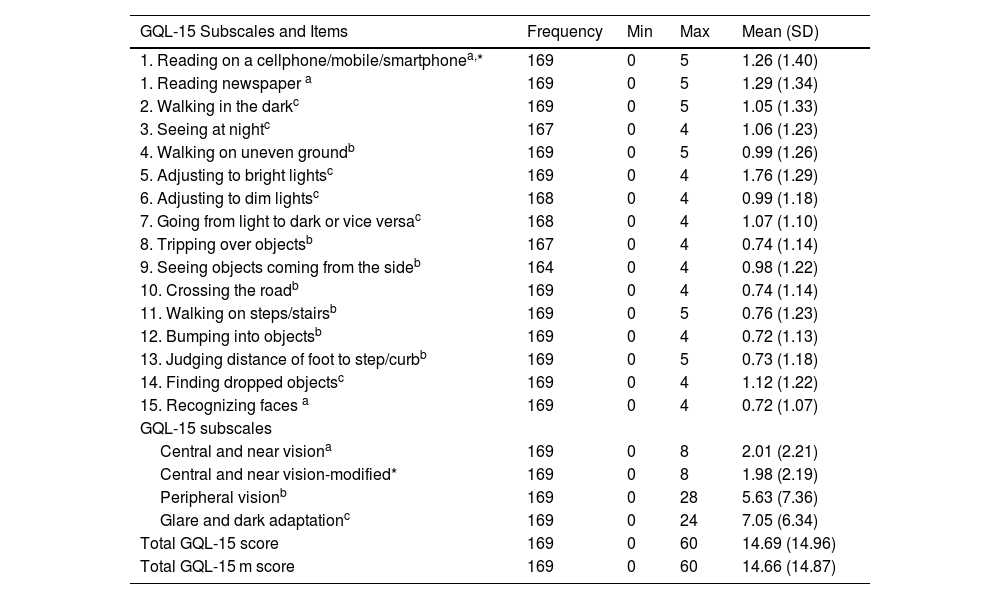

ParticipantsOut of 934 eligible individuals, 468 were randomly selected for outreach, and 169 ultimately participated in the survey (36.1% response rate). Participants had a mean age of 66.76 years ±12.33; most were over 65 years (62.72%), followed by those aged 45–65 years (31.95%) and 18–44 years (5.33%). The sample was predominantly female (61.54%). Regarding education, most participants had a technical or university degree (36.09%), followed by those who completed primary (32.54%) or high school (28.40%); a small fraction had not attended school (2.37%). Socioeconomic status was mostly middle (47.34%), followed by low (31.95%) and upper (10.06%) income, with 10.65% missing data. The mean visual acuity in LogMAR was 0.25 ± 0.08 for the better eye and 0.90 ± 1.44 for the worse eye. The GQL-15 mean total score was 29.3 ± 7.31. Table 1 shows the item and domain scores of the GQL-15 and GQL-15 m for the study population.

GQL-15 and GQL-15 m Scores by Items and Subscales in Spanish-Speaking Participants (n = 169).

| GQL-15 Subscales and Items | Frequency | Min | Max | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Reading on a cellphone/mobile/smartphonea,* | 169 | 0 | 5 | 1.26 (1.40) |

| 1. Reading newspaper a | 169 | 0 | 5 | 1.29 (1.34) |

| 2. Walking in the darkc | 169 | 0 | 5 | 1.05 (1.33) |

| 3. Seeing at nightc | 167 | 0 | 4 | 1.06 (1.23) |

| 4. Walking on uneven groundb | 169 | 0 | 5 | 0.99 (1.26) |

| 5. Adjusting to bright lightsc | 169 | 0 | 4 | 1.76 (1.29) |

| 6. Adjusting to dim lightsc | 168 | 0 | 4 | 0.99 (1.18) |

| 7. Going from light to dark or vice versac | 168 | 0 | 4 | 1.07 (1.10) |

| 8. Tripping over objectsb | 167 | 0 | 4 | 0.74 (1.14) |

| 9. Seeing objects coming from the sideb | 164 | 0 | 4 | 0.98 (1.22) |

| 10. Crossing the roadb | 169 | 0 | 4 | 0.74 (1.14) |

| 11. Walking on steps/stairsb | 169 | 0 | 5 | 0.76 (1.23) |

| 12. Bumping into objectsb | 169 | 0 | 4 | 0.72 (1.13) |

| 13. Judging distance of foot to step/curbb | 169 | 0 | 5 | 0.73 (1.18) |

| 14. Finding dropped objectsc | 169 | 0 | 4 | 1.12 (1.22) |

| 15. Recognizing faces a | 169 | 0 | 4 | 0.72 (1.07) |

| GQL-15 subscales | ||||

| Central and near visiona | 169 | 0 | 8 | 2.01 (2.21) |

| Central and near vision-modified* | 169 | 0 | 8 | 1.98 (2.19) |

| Peripheral visionb | 169 | 0 | 28 | 5.63 (7.36) |

| Glare and dark adaptationc | 169 | 0 | 24 | 7.05 (6.34) |

| Total GQL-15 score | 169 | 0 | 60 | 14.69 (14.96) |

| Total GQL-15 m score | 169 | 0 | 60 | 14.66 (14.87) |

SD, Standard deviation.

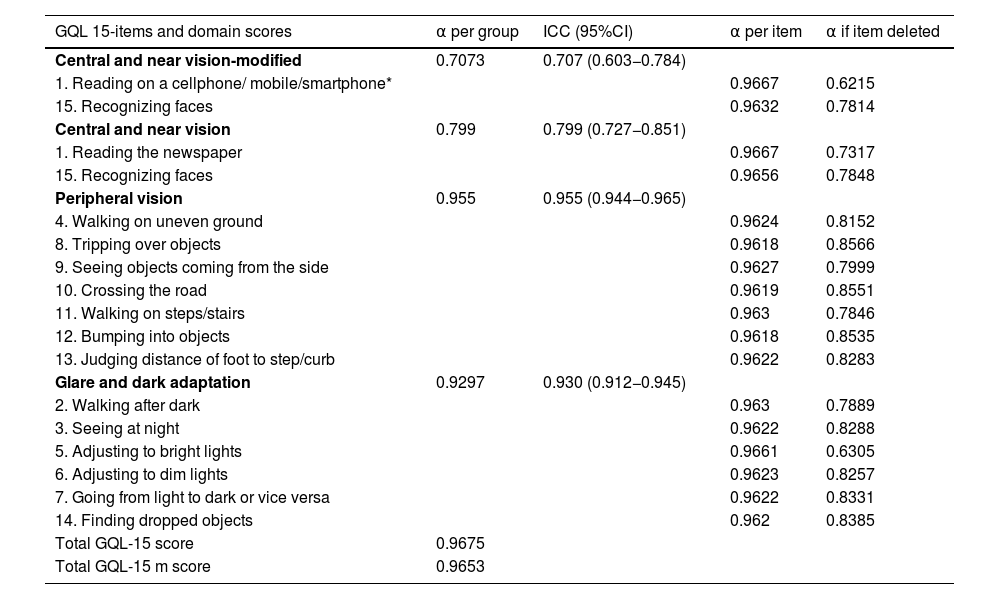

The KMO test was 0.9407. The Scree plot analysis revealed two factors with eigenvalues >1; however, factorial analysis yielded three factors capturing 96% of variability. The GQL-15 and GQL-15-m showed similar internal consistency (α 0.9675 and 0.9653). 'Peripheral vision' and 'Glare and dark adaptation' subscales had satisfactory α, while 'Central and near vision' had relatively lower coefficients in both modified (0.7986) and original (0.7073) versions (Table 2).

Cronbach's Alpha (α) Coefficients for the Validation of the Spanish version of the Glaucoma Quality of Life Questionnaire – 15 (GQL-15) and GQL-15 modified (GQL-15 m).

| GQL 15-items and domain scores | α per group | ICC (95%CI) | α per item | α if item deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central and near vision-modified | 0.7073 | 0.707 (0.603−0.784) | ||

| 1. Reading on a cellphone/ mobile/smartphone* | 0.9667 | 0.6215 | ||

| 15. Recognizing faces | 0.9632 | 0.7814 | ||

| Central and near vision | 0.799 | 0.799 (0.727−0.851) | ||

| 1. Reading the newspaper | 0.9667 | 0.7317 | ||

| 15. Recognizing faces | 0.9656 | 0.7848 | ||

| Peripheral vision | 0.955 | 0.955 (0.944−0.965) | ||

| 4. Walking on uneven ground | 0.9624 | 0.8152 | ||

| 8. Tripping over objects | 0.9618 | 0.8566 | ||

| 9. Seeing objects coming from the side | 0.9627 | 0.7999 | ||

| 10. Crossing the road | 0.9619 | 0.8551 | ||

| 11. Walking on steps/stairs | 0.963 | 0.7846 | ||

| 12. Bumping into objects | 0.9618 | 0.8535 | ||

| 13. Judging distance of foot to step/curb | 0.9622 | 0.8283 | ||

| Glare and dark adaptation | 0.9297 | 0.930 (0.912−0.945) | ||

| 2. Walking after dark | 0.963 | 0.7889 | ||

| 3. Seeing at night | 0.9622 | 0.8288 | ||

| 5. Adjusting to bright lights | 0.9661 | 0.6305 | ||

| 6. Adjusting to dim lights | 0.9623 | 0.8257 | ||

| 7. Going from light to dark or vice versa | 0.9622 | 0.8331 | ||

| 14. Finding dropped objects | 0.962 | 0.8385 | ||

| Total GQL-15 score | 0.9675 | |||

| Total GQL-15 m score | 0.9653 |

GQL-15: Glaucoma Quality of Life-15.

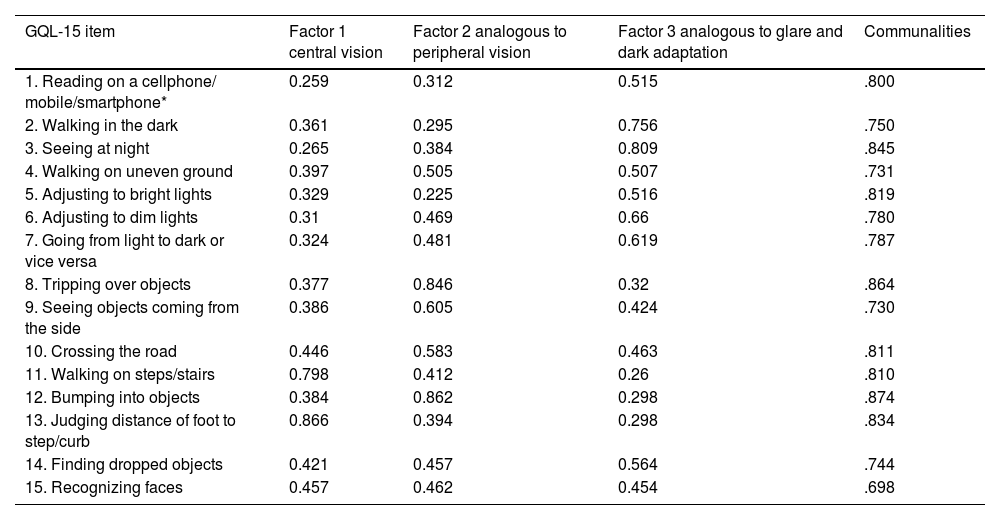

All individual items showed α above 0.70 for internal consistency (Table 3). Removing 'reading on a cellphone/mobile/smartphone' had a greater impact on reliability than 'reading the newspaper,' reducing α to 0.6215. The exploratory factor analysis identified three distinct factors—Central Vision, Peripheral Vision, and Glare and Dark Adaptation (Fig. 1)—with communalities ranging from 0.698 to 0.874, indicating that these factors explain a significant portion of the variance and are well-defined.

Exploratory factor analysis of modified version of Glaucoma Quality of Life-15 (GQL-15 m) questionnaire with communalities and Cronbach’s coefficients for each factor.

| GQL-15 item | Factor 1 central vision | Factor 2 analogous to peripheral vision | Factor 3 analogous to glare and dark adaptation | Communalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Reading on a cellphone/ mobile/smartphone* | 0.259 | 0.312 | 0.515 | .800 |

| 2. Walking in the dark | 0.361 | 0.295 | 0.756 | .750 |

| 3. Seeing at night | 0.265 | 0.384 | 0.809 | .845 |

| 4. Walking on uneven ground | 0.397 | 0.505 | 0.507 | .731 |

| 5. Adjusting to bright lights | 0.329 | 0.225 | 0.516 | .819 |

| 6. Adjusting to dim lights | 0.31 | 0.469 | 0.66 | .780 |

| 7. Going from light to dark or vice versa | 0.324 | 0.481 | 0.619 | .787 |

| 8. Tripping over objects | 0.377 | 0.846 | 0.32 | .864 |

| 9. Seeing objects coming from the side | 0.386 | 0.605 | 0.424 | .730 |

| 10. Crossing the road | 0.446 | 0.583 | 0.463 | .811 |

| 11. Walking on steps/stairs | 0.798 | 0.412 | 0.26 | .810 |

| 12. Bumping into objects | 0.384 | 0.862 | 0.298 | .874 |

| 13. Judging distance of foot to step/curb | 0.866 | 0.394 | 0.298 | .834 |

| 14. Finding dropped objects | 0.421 | 0.457 | 0.564 | .744 |

| 15. Recognizing faces | 0.457 | 0.462 | 0.454 | .698 |

The GQL-15 m total score showed significant positive correlations with several domains of the NEI-VFQ 25 (Table 4); however, significant negative correlations were observed with the NEI-VFQ 25 domains ‘mental health,’ ‘dependency on others,’ and ‘driving difficulty.’ Additionally, no significant correlations were found between the GQL-15 m domains ‘central/near vision’ and ‘glare/dark adaptation’ and the NEI-VFQ 25 domain ‘ocular pain. Similar patterns are observed with the WHOQoL-BREF, with negative correlations with Physical and Environmental Dimensions. The GQL-15 m also has strong positive correlations with the GUI subscales and the GSS Functional Impact Subscale.

Correlation of 15-Item Glaucoma Quality of Life Questionnaire (GQL-15 m) Subscales and Total Score with National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (NEI-VFQ 25), World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQoL-BREF), Glaucoma Symptom Scale (GSS), Glaucoma Utility Index (GUI), and Patient Demographic and Visual Acuity.

| Parameters | GQL-15 m central/near vision | GQL-15 m peripheral vision | GQL-15 m glare/dark adaptation | GQL-15 m total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total NEI VFQ-25 | 0.380 (<0.001) | 0.375 (<0.001) | 0.392 (<0.001) | 0.399 (<0.001) |

| General health | 0.627 (<0.001) | 0.591 (<0.001) | 0.634 (<0.001) | 0.672 (<0.001) |

| General vision | 0.231 (0.003) | 0.295 (<0.001) | 0.268 (<0.001) | 0.287 (<0.001) |

| Ocular pain | 0.134 (0.08) | −0.162 (0.036) | −0.054 (0.48) | −0.046 (0.55) |

| Near vision | 0.739 (<0.001) | 0.719 (<0.001) | 0.745 (<0.001) | 0.803 (<0.001) |

| Distant vision | 0.572 (<0.001) | 0.774 (<0.001) | 0.699 (<0.001) | 0.760 (<0.001) |

| Social functioning | 0.496 (<0.001) | 0.433 (<0.001) | 0.469 (<0.001) | 0.504 (<0.001) |

| Mental health | −0.584 (0.37) | −0.573 (<0.001) | −0.569 (<0.001) | −0.615 (<0.001) |

| Role limitation | 0.375 (0.009) | 0.567 (<0.001) | 0.505 (<0.001) | 0.544 (<0.001) |

| Dependency on others | −0.744 (<0.001) | −0.684 (<0.001) | −0.737 (<0.001) | −0.786 (<0.001) |

| Driving difficulty | −0.361 (<0.001) | −0.421 (<0.001) | −0.385 (<0.001) | −0.431 (<0.001) |

| Color vision | 0.630 (<0.001) | 0.639 (<0.001) | 0.607 (<0.001) | 0.649 (<0.001) |

| Peripheral vision | 0.557 (<0.001) | 0.545 (<0.001) | 0.505 (<0.001) | 0.561 (<0.001) |

| WHOQoL-BREF | ||||

| Physical | −0.369 (<0.001) | −0.511 (<0.001) | −0.431 (<0.001) | −0.268 (<0.001) |

| Psychological | −0.129 (0.109) | −0.196 (0.014) | −0.199 (0.013) | −0.127 (0.114) |

| Additional Psychological | −0.231 (0.004) | −0.255 (0.001) | −0.237 (0.003) | −0.109 (0.177) |

| Environmental | −0.342 (<0.001) | −0.299 (<0.001) | −0.299 (<0.001) | −0.349 (<0.001) |

| GSS | ||||

| Symptom Severity | 0.339 (<0.001) | 0.387 (<0.001) | 0.475 (<0.001) | 0.169 (0.035) |

| Functional Impact | 0.731 (<0.001) | 0.675 (<0.001) | 0.796 (<0.001) | 0.349 (<0.001) |

| GUI | ||||

| Central and Near Vision | 0.734 (<0.001) | 0.676 (<0.001) | 0.658 (<0.001) | 0.734 (<0.001) |

| Lighting and Glare | 0.704 (<0.001) | 0.621 (<0.001) | 0.796 (<0.001) | 0.765 (<0.001) |

| Mobility | 0.736 (<0.001) | 0.773 (<0.001) | 0.678 (<0.001) | 0.739 (<0.001) |

| Daily Life Activities | 0.734 (<0.001) | 0.727 (<0.001) | 0.648 (<0.001) | 0.729 (<0.001) |

| Ocular Discomfort | 0.299 (<0.001) | 0.303 (<0.001) | 0.353 (<0.001) | 0.333 (<0.001) |

| Other Effects | 0.271 (<0.001) | 0.269 (<0.001) | 0.331 (<0.001) | 0.314 (<0.001) |

| Patients’ characteristics | ||||

| Age | −0.154 (0.046) | −0.085 (0.27) | −0.131 (0.09) | −0.018 (0.17) |

| Sex | −0.168 (0.03) | 0.011 (0.89) | 0.001 (0.98) | 0.087 (0.26) |

| Education level | 0.042 (0.59) | 0.042 (0.58) | 0.057 (0.46) | −0.076 (0.32) |

| Socioeconomic status | −0.232 (0.002) | −0.124 (0.11) | −0.127 (0.1) | −0.099 (0.2) |

| Visual acuity | ||||

| Better eye visual acuity | 0.353 (<0.001) | 0.326 (<0.001) | 0.313 (<0.001) | 0.341 (<0.001) |

| Worse eye visual acuity | 0.363 (<0.001) | 0.358 (<0.001) | 0.360 (<0.001) | 0.377 (<0.001) |

Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient [ρ] (probability values). Gray areas show significant negative correlations.

Significant negative correlations were observed between the GQL-15 m ‘central/near vision’ domain and patient characteristics, including age, sex, and socioeconomic status. Visual acuity in both the better and worse eyes showed moderate positive correlations with all GQL-15 m domains, emphasizing the relationship between visual impairment and QoL (Table 4).

Sixty-four percent of participants completed the retest assessment, and we obtained an ICC of 0.89.

DiscussionGlaucoma is a major global health concern that significantly impacts QoL.1,2 The GQL-15 has been used widely and it is recognized as an accessible and effective tool to measure QoL in glaucoma.12 To our knowledge, this is the first study aiming to validate the GQL-15 for use in Spanish-speaking population and to develop a modified version (GQL-15 m) updating the survey. The findings of this study offer valuable insights into the psychometric properties and cultural adaptation of the GQL-15, making it suitable for use in Latino or Hispanic populations.

Vision loss profoundly impacts an individual’s life, affecting physical health and various psychological and social dimensions.20,21 Vision-related QoL covers four dimensions: physical (disease symptoms and treatment), functional (self-care, mobility, activity level, and daily activities), social (social contact and interpersonal relationships), and psychological (cognitive function, emotional state, well-being).22 Evaluating the QoL of individuals with glaucoma is crucial, as it provides a baseline for assessment of interventions aimed at improving patient outcomes.23 Assessing QoL also helps identify psychosocial comorbidities, enabling a more holistic approach to care.24 Additionally, accurate QoL data can inform resource allocation and policy decisions.25 Despite the multidimensional nature of QoL and the inherent challenges in its measurement, the GQL-15 and GQL-15 m, while briefs, exhibit strong psychometric properties in assessing key QoL domains.

In our increasingly globalized world, characterized by widespread and immediate access to online information, the GQL-15 required a modernization.26 For instance, the number of individuals who still read newspapers has been steadily declining,27 prompting us to consider making the ‘reading the newspaper’ question optional. Instead, including the item ‘reading on a cellphone/mobile/smartphone’ ensures the timely nature of the survey while guarantying its robustness and reliability as per the resulted α. This update enhances the instrument’s relevance and ensures it accurately reflects contemporary habits.

Exploratory factor analysis revealed three primary factors explaining 93% of the data variance in the GQL-15 m: central and near vision, peripheral vision, and glare/dark adaptation. These findings aligned with the initial content validity, supporting the questionnaire's construct validity among the Colombian population. We decided to remove the domain for ‘Outdoor mobility’ as it was composed of only one item, thus the internal consistency was not possible to evaluate. Instead of having a single question in that domain (‘Adjusting to bright lights’), we added it to the domain of ‘Glare and dark adaptation’ where it showed a good correlation with the items in the group as well as a good reliability.

When comparing our study with those by Goldberg and Zhou in Serbia and China, α values were 0.89 and 0.75−0.91, with reproducibility (ICC) of 0.96 and 0.70, respectively.13,14 The overall internal consistency (α) for both the GQL-15 and GQL-15 m was excellent, indicating strong correlation between items. However, the ‘Central and Near Vision’ subscale exhibited a lower α, indicating that this aspect of the questionnaire may require further refinement.

Removing the item 'Reading on a cellphone/mobile/smartphone' results in a substantial α decrease to 0.6215, while excluding 'Reading the newspaper' leads to a decrease to 0.7317, though this effect is less pronounced. These results underscore the pivotal role of smart devices in upholding the questionnaire's reliability. Retaining this item is crucial for the tool's robustness in assessing QoL in glaucoma, vital for future research and clinical use.

In today’s digital age, cellphones have become tools for work and entertainment, with people spending over 50% of their time on screens.28–30 The bright light from screens can cause glare, discomfort, and visual strain, making reading challenging for those with visual impairments.31 Prolonged screen use also leads to fatigue, headaches, and blurred vision.32,33 In contrast, reading physical newspapers has declined among younger generations.27 Given the prevalence of mobile devices, the inability to read on a cellphone poses a greater concern, underscoring the importance of replacing the newspaper item to reflect contemporary habits.

Significant correlations with established visual function and QoL measures confirmed the GQL-15 m's criterion validity.9,34,35 Positive correlations with NEI VFQ-25 subscales, particularly 'Near Vision' and 'Distant Vision,' align with prior studies, validating both tools' ability to capture functional limitations caused by glaucoma.34–37 In contrast, negative correlations with NEI VFQ-25 domains like 'Mental Health,' 'Dependency on Others,' and 'Driving Difficulty' underscore the GQL-15 m's effectiveness in assessing the psychosocial and practical challenges of glaucoma. These findings, consistent with Varma et al., show how glaucoma affects social functioning, independence, and overall QoL.36

Moreover, the GQL-15 m's correlations with the WHOQoL-BREF Physical and Environmental dimensions suggest its broader use in assessing general health-related QoL in glaucoma patients.38 The WHOQoL-BREF 's effectiveness in chronic diseases supports the GQL-15 m's relevance across diverse contexts.38 T Strong correlations with the GUI subscales, such as ‘Central and Near Vision’ and ‘Lighting and Glare,’ further validate its alignment with existing visual function tools, confirming its utility in clinical and research settings.39 Future studies should explore the GQL-15 m's criterion validity in various cultural contexts to enhance its applicability.

The test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.89) indicates consistent responses to the GQL-15 m over time, validating its stability in measuring QoL in glaucoma patients. This reliability supports its broader applicability across diverse populations and reinforces its utility in both clinical practice and research settings.40

Study limitationsWhile this study provides valuable insights into the psychometric properties of the GQL-15 and GQL-15 m in the Colombian population, certain limitations should be considered. First, the response rate of 33% may introduce selection bias, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings to the broader Spanish-speaking population with glaucoma. Additionally, we lacked comprehensive clinical information on glaucoma severity using standardized measurements such as visual field indices (e.g., mean deviation [MD]). Although visual field testing is performed in both institutions, these data were not fully accessible in the patient databases provided for the study. To address this limitation, we used visual acuity as an indirect measure of disease severity. While visual acuity is a relevant and widely available clinical parameter, it is a less specific indicator of glaucoma severity compared to functional assessments like visual field MD. Future studies should aim to incorporate standardized glaucoma severity measurements to further validate the applicability of the GQL-15 m in diverse clinical settings.

Future directionsAs this study focuses on a Spanish-speaking population and incorporates updates for modern contexts, we believe the GQL-15 m instrument is valid and applicable in diverse cultural and linguistic settings globally. This can facilitate cross-cultural comparisons and improve understanding of glaucoma's impact on daily living.

ConclusionThis study validated the Spanish version of the GQL-15 and introduced the GQL-15 m, updated to reflect modern technological usage and specifically adapted for the Spanish-speaking population. The results demonstrated that both instruments possess strong psychometric properties, including reliability, validity, and consistency. The GQL-15 m is a valuable tool for assessing the impact of glaucoma on QoL in Spanish-speaking populations worldwide.

Ethics statementThe study received ethical approval from the Universidad del Valle (approval No. 022-021), the Hospital Universitario del Valle (approval No. 055-2021), and the Ophthalmology Clinic of Cali (approval No. COC – CIC 055). All participants provided informed consent, having listened to, understood, and accepted the terms before the questionnaire was administered. This research adheres to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration, ensuring ethical standards were upheld throughout the study.

Financial disclosureThe present research has not received specific funding from public sector agencies or commercial entities. It was partially funded by the non-profit Fundación Somos Ciencia al Servicio de la Comunidad, Fundación SCISCO / Science to Serve the Community Foundation, SCISCO Foundation, Cali, Colombia.

None.

To all the patients in the Hospital Universitario del Valle and the Clínica Oftalmológica de Cali for participating in the study.