Background. It has been suggested that DM may reduce survival of patients with liver cirrhosis (LC). Nevertheless only few prospective studies assessing the impact of DM on mortality of cirrhotic patients have been published, none in compensated LC.

Aims. (i) to study the impact of DM on mortality and (ii) to identify predictors of death.

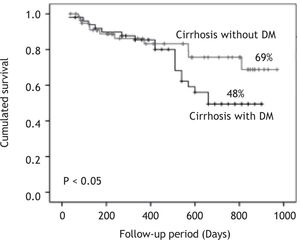

Methods. Patients with compensated LC with and without DM were studied. Survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier Method. Univariate and multivariate analysis was performed to determine independent predictors of mortality.

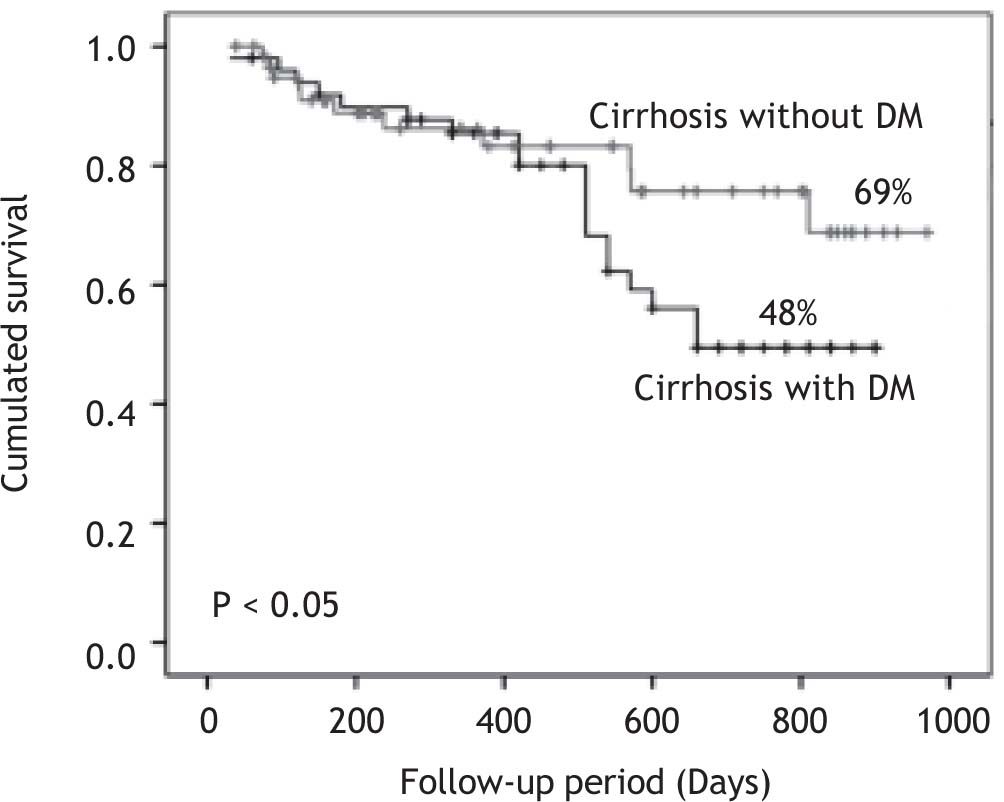

Results. 110 patients were included: 60 without DM and 50 with DM. Diabetic patients had significantly higher frequency of cryptogenic cirrhosis, anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and hypercreatininemia. They also had significantly higher BMI and Child-Pugh score. The 2.5-years cumulative survival was significantly lower in patients with DM (48 vs. 69%, p < 0.05). By univariate analysis: DM, female gender, serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL, Child-Pugh score class C and cryptogenic cirrhosis were significant. However, only serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL and Child-Pugh score class C were independent predictors of death.

Conclusion: DM was associated with a significant increase in mortality in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. Serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL and Child-Pugh score class C were independent predictors of death.

Overt diabetes mellitus (DM) may be observed in 30 to 40% of patients with liver cirrhosis.1 However, impaired glucose tolerance and subclinical DM have been identified by oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in about 38 and 25% of cases, respectively, in cirrhotic patients with no previous history of DM and with normal fasting glucose levels.2-4 The DM is clinically apparent in advanced stages of liver disease.5 The occurrence of DM may be a result of a progressive disorder of insulin secretion in the presence of hepatic insulin resistance.6,7

There are 2 types of diabetes associated with chronic liver disease:

- •

Type 2 DM, that along with obesity and hypertri-glyceridemia, is the so-called metabolic syndrome which can cause fatty liver, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver cirrhosis.

- •

The so-called hepatogenous diabetes that follows liver cirrhosis, mainly those caused by hepatitis C virus, alcohol, and hemochromatosis.8-10

Retrospective studies have shown that the DM (either type 2 or hepatogenous) increases the risk of complications of cirrhosis of any etiology and reduces survival.7,11-14 The DM exacerbates hepatic inflammation and accelerates the production of fibrosis leading to severe liver failure.15 According to a population-based study of 7,000 subjects with type 2 DM, it was found that the risk of death at 5 years was 2.52 times higher than in the general population.16

The incidence of obesity has increased in recent years worldwide, particularly in the West World. In Mexico, 50% of the adult population has obesity, a figure that places it in second place worldwide only behind the U.S. The incidence of DM and metabolic syndrome has rapidly increased in our population due to this situation. It was recently shown that the type 2 DM and the metabolic syndrome are the most common cause of cryptogenic cirrhosis in Mexico.17,18

Despite the previously discussed issues, only few prospective studies assessing the impact of DM on morbidity and mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis have been published.11,19 Moreover, the presence of glucose intolerance and subclinical diabetes by OGTT is not routinely investigated in cirrhotic patients without known DM.

Based on the above, the objectives of the present study were: (i) to study prospectively the impact of overt DM on mortality of patients with compensated liver cirrhosis of any etiology and (ii) to identify predictors of mortality in this group of patients.

Material and MethodsPatientsWe prospectively included patients with compensated liver cirrhosis who were admitted in the Regional Center for the Study of Digestive Diseases and the Liver Unit of the University Hospital and Faculty of Medicine. Also the Medical Unit of High Specialty No. 25 of the Mexican Institute of Social Security of Monterrey N.L. patients who were admitted from August 2007 to March 2010. The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Autonomous University of Nuevo León in Monterrey

Inclusion criteria were: the presence of biopsy-or clinically diagnosed liver cirrhosis; clinically compensated cirrhosis; age above 18 years; and any sex.

Compensated cirrhosis was defined as the absence of: visible GI hemorrhage, clinical hepatic encephalopathy, severe ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, infection, hepatorenal syndrome, alcoholic hepatitis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

After including all patients, two groups of patients were formed based on the following: Group 1 consisted of patients without a previous history of DM and with normal fasting serum glucose levels; and Group 2 consisted of patients with overt DM. Diagnosis of diabetes was defined based on the criteria of the American Diabetes Association.20

MethodsDemographic, clinical and biochemical variables were recorded in a database especially designed for this research; additionally, Child-Pugh and MELD scores were calculated.21

All patients were followed-up every 3 months by outpatient department of each institution that participated in the study. A full clinical examination was made in each interview. Laboratory tests (serum hemoglobin, hematocrit, blood cell count, serum glucose, serum creatinine, BUN, liver function tests and coagulation tests) were performed. Moreover, blood alpha-fetoprotein and liver ultrasound were performed every 6 months. Additionally, hospital admissions were recorded during which clinical course was observed.

Patients who did not attend outpatient appointments were contacted them or their family members by telephone to determine the clinical status or to inquire whether their death occurred. Diabetic patients were treated in the Department of Endocrinology of our institution using the clinical protocols of the treatment of DM. These protocols included dietary measures, oral hypoglycemic agents, or subcutaneous insulin based on individual requirements.

The main endpoint of the study was the occurrence of death, whose cause was classified as associated with liver cirrhosis or DM. Mortality related with liver cirrhosis was defined as deaths occurred due to complications of cirrhosis: upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, liver failure and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations, non-continuous variables as medians and ranges, and categorical variables as relative proportions.

Intergroup comparisons were made by Student t, Chi-square and Mann-Whitney tests. Variables were analyzed using multivariate Cox’s proportional hazard model to determine independent predictive factors of mortality.22 Only the variables that were significant in univariate analysis were analyzed in multivariate analysis. The results were expressed as odds ratios (OR) and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals, and p-value was calculated.

The cumulative survival of patients with and without DM was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. The cumulative survival between groups was compared using log-rank test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were done using the statistical package SPSS v17.0 (Chicago, Illinois, USA).

ResultsPatient populationOne hundred and ten patients with compensated liver cirrhosis were included in the study, of which 57 (51.2%) were male. The mean age was 56.7 ± 11.7 years (range 27-87). The causes of liver cirrhosis were: alcohol in 45 patients (40.9%), cryptogenic in 42 (38.1%), hepatitis C virus in 15 (13.6%), hepatitis B virus in 3 (2.7%), and autoimmunity in 7 (6.3%). The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was made by biopsy in 35 patients (31.8%), and in the remaining patients it was done clinically on the basis of the imaging studies. The median duration of liver cirrhosis was 41 months (range 1-144 months) before inclusion in the study. In relation to the Child-Pugh score, 54 (49%) patients belonged to stage A, 44 (40%) patients belonged to stage B and 12 (11%) patients belonged to at stage C. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 27.3 ± 4.5; 27 (24.5%) patients were obese (BMI over 30). On the other hand, 50 (45%) patients (95% CI: 35.8-54.2) met the clinical criteria for diagnosis of DM.

Patients with and without DMGroup 1 consisted of 60 patients without DM and Group 2 consisted of 50 patients with DM. The diagnosis of DM was made in a mean of 107.4 months (range 1-300 months) before inclusion in the study. The diagnosis of DM was made before the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis in 32 (64%) patients; it was made after the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis in 8 (16%) patients; and it was made simultaneously in 10 (20%) patients. Before inclusion, the DM was treated for the last 6 months by diet and dietetic-hygienic measures only in 5 cases (10%), oral hypoglycemic agents in 22 (44%) patients, and subcutaneous insulin in 23 (46%) patients. During the follow up 2 (4%) patients were treated by diet, 20 (40%) patients received oral hypoglycemic agents and 28 (56%) required subcutaneous insulin.

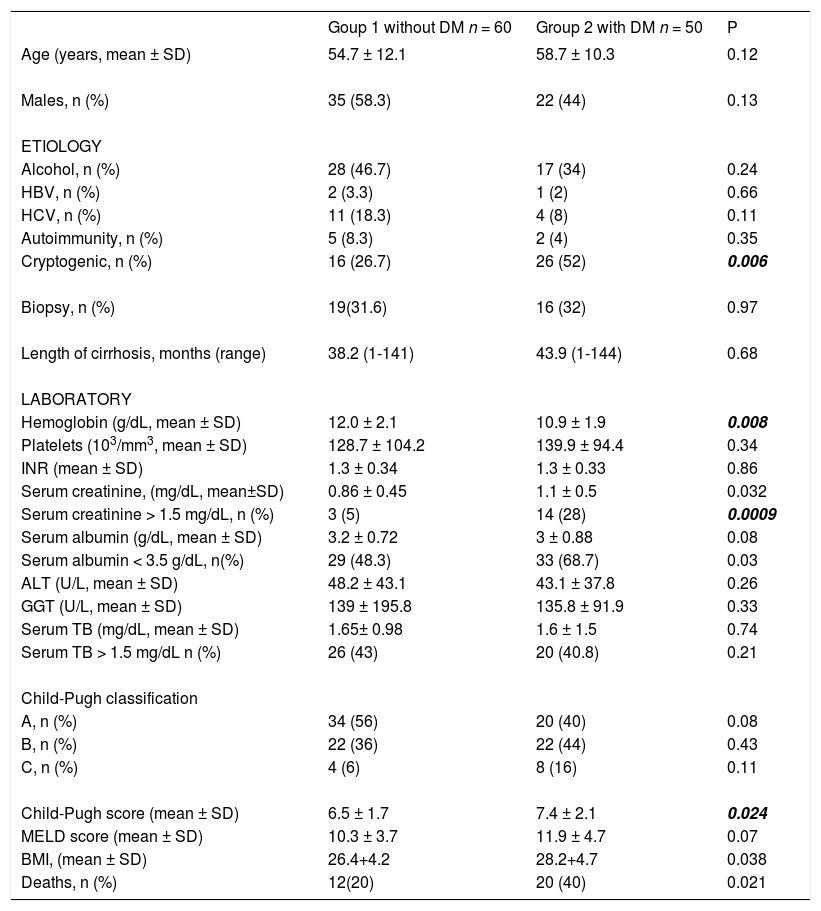

The demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients in Groups 1 and 2 are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences regarding age, gender and time of diagnosis of liver cirrhosis. By contrast, the proportion of patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis was significantly higher in the DM group, 26 (52%) vs. 16 (26.7%) (p = 0.006).

Clinical and biochemical characteristics of cirrhotic patients with and without diabetes mellitus.

| Goup 1 without DM n = 60 | Group 2 with DM n = 50 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 54.7 ± 12.1 | 58.7 ± 10.3 | 0.12 |

| Males, n (%) | 35 (58.3) | 22 (44) | 0.13 |

| ETIOLOGY | |||

| Alcohol, n (%) | 28 (46.7) | 17 (34) | 0.24 |

| HBV, n (%) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (2) | 0.66 |

| HCV, n (%) | 11 (18.3) | 4 (8) | 0.11 |

| Autoimmunity, n (%) | 5 (8.3) | 2 (4) | 0.35 |

| Cryptogenic, n (%) | 16 (26.7) | 26 (52) | 0.006 |

| Biopsy, n (%) | 19(31.6) | 16 (32) | 0.97 |

| Length of cirrhosis, months (range) | 38.2 (1-141) | 43.9 (1-144) | 0.68 |

| LABORATORY | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL, mean ± SD) | 12.0 ± 2.1 | 10.9 ± 1.9 | 0.008 |

| Platelets (103/mm3, mean ± SD) | 128.7 ± 104.2 | 139.9 ± 94.4 | 0.34 |

| INR (mean ± SD) | 1.3 ± 0.34 | 1.3 ± 0.33 | 0.86 |

| Serum creatinine, (mg/dL, mean±SD) | 0.86 ± 0.45 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 0.032 |

| Serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL, n (%) | 3 (5) | 14 (28) | 0.0009 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL, mean ± SD) | 3.2 ± 0.72 | 3 ± 0.88 | 0.08 |

| Serum albumin < 3.5 g/dL, n(%) | 29 (48.3) | 33 (68.7) | 0.03 |

| ALT (U/L, mean ± SD) | 48.2 ± 43.1 | 43.1 ± 37.8 | 0.26 |

| GGT (U/L, mean ± SD) | 139 ± 195.8 | 135.8 ± 91.9 | 0.33 |

| Serum TB (mg/dL, mean ± SD) | 1.65± 0.98 | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 0.74 |

| Serum TB > 1.5 mg/dL n (%) | 26 (43) | 20 (40.8) | 0.21 |

| Child-Pugh classification | |||

| A, n (%) | 34 (56) | 20 (40) | 0.08 |

| B, n (%) | 22 (36) | 22 (44) | 0.43 |

| C, n (%) | 4 (6) | 8 (16) | 0.11 |

| Child-Pugh score (mean ± SD) | 6.5 ± 1.7 | 7.4 ± 2.1 | 0.024 |

| MELD score (mean ± SD) | 10.3 ± 3.7 | 11.9 ± 4.7 | 0.07 |

| BMI, (mean ± SD) | 26.4+4.2 | 28.2+4.7 | 0.038 |

| Deaths, n (%) | 12(20) | 20 (40) | 0.021 |

HBV: Hepatitis B Virus. HCV: Hepatitis C virus. INR: International normalized ratio. MELD: Model for end stage liver disease. BMI: Body mass index. TB: Total bilirubin.

Through laboratory tests, it was found that diabetic patients had significantly higher frequency of anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and hypercreatininemia than non-diabetic ones. Additionally, diabetic patients had significantly higher BMI and higher Child-Pugh score.

On the other side, 36 and 35% of the alcoholic patients stopped drinking, in group 1 and group 2, respectively. Moreover, 45 and 50% of the patients with hepatitis C virus infection, in group 1 and group 2 respectively, received antiviral treatment. While, 50% in group 1 and 0% in group 2 of patients with hepatitis B virus infection were treated. And, 80 and 100% of the patients with autoimmunity, in group 1 and group 2 respectively, received immunosuppressive therapy.

MortalityThe mean follow-up of the patients was 426 ± 299 (range 39-970) days in group 1 and 499 ± 241 (range 30-900) days in group 2. There were no drop outs in the follow up of the patients. The survival curve of patients in both groups is shown in Figure 1. Patients with DM had cumulative survival significantly lower than patients without DM. The difference in the survival curves began to become evident after 400-day follow-up; and cumulative survival was 69% in patients without DM and 48% in patients with DM (p < 0.05) after 900-day follow-up.

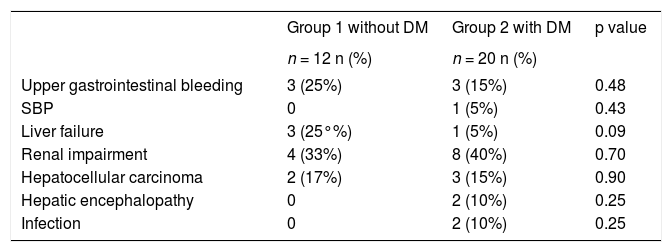

At the end of follow-up, 12 patients without DM and 20 patients with DM died. The causes of death are shown in Table 2. Most patients with DM died of liver and kidney complications. There were no cardiovascular or cerebrovascular complications.

Cause of death in patients with and without diabetes mellitus.

| Group 1 without DM | Group 2 with DM | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 12 n (%) | n = 20 n (%) | ||

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 3 (25%) | 3 (15%) | 0.48 |

| SBP | 0 | 1 (5%) | 0.43 |

| Liver failure | 3 (25°%) | 1 (5%) | 0.09 |

| Renal impairment | 4 (33%) | 8 (40%) | 0.70 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 2 (17%) | 3 (15%) | 0.90 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 0 | 2 (10%) | 0.25 |

| Infection | 0 | 2 (10%) | 0.25 |

SBP: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

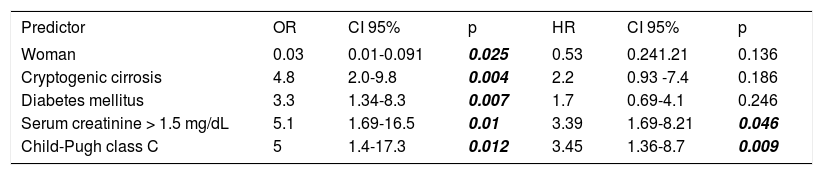

The following variables were statistically significant in the univariate analysis: DM (OR: 3.3, 95% CI: 1.34-8.3, p = 0.007), female gender (OR: 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1-0.91, p = 0.025), serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/ dL (OR: 5.1, 95% CI: 1.6-16.5, p = 0.01), Child-Pugh score class C (OR: 5, 95% CI: 1.4-17.3, p = 0.012), and cryptogenic cirrhosis (OR: 4.8, 95% CI: 2.0-9.8, p = 0.004). However, only the following parameters were independent predictors of death in multivariate analysis: serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL (HR: 3.45, 95% CI: 1.36-8.7, p = 0.009), and Child-Pugh score class C (HR: 3.45, 95% CI: 1.36-8.7, p = 0.009) (Table 3).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of predictors of death in patients with and without diabetes mellitus.

| Predictor | OR | CI 95% | p | HR | CI 95% | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woman | 0.03 | 0.01-0.091 | 0.025 | 0.53 | 0.241.21 | 0.136 |

| Cryptogenic cirrosis | 4.8 | 2.0-9.8 | 0.004 | 2.2 | 0.93 -7.4 | 0.186 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.3 | 1.34-8.3 | 0.007 | 1.7 | 0.69-4.1 | 0.246 |

| Serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL | 5.1 | 1.69-16.5 | 0.01 | 3.39 | 1.69-8.21 | 0.046 |

| Child-Pugh class C | 5 | 1.4-17.3 | 0.012 | 3.45 | 1.36-8.7 | 0.009 |

Although it is well known that metabolic syndrome causes fatty liver, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma,23,24 it has been suggested that DM alone is a risk factor for chronic liver disease. In a recently published study conducted in an open population of 438,000 patients with type 2 DM and 2,059,000 controls, it was observed that after adjusting for obesity, dyslipidemia and arterial hypertension, diabetic subjects had a 2 times greater risk of developing serious liver disease than non-diabetic subjects.25 On the other hand, an increased frequency of insulin resistance, glucose intolerance and DM was observed in the patients with no history of type-2 diabetes and with chronic liver disease caused by HCV, alcohol, and hemochromatosis. This frequency was higher than in patients with chronic liver disease caused by hepatitis B virus, autoimmunity, and cholestasis.26-28

In the hepatitis C virus infection, insulin resistance and diabetes are more frequently associated with genotype 1 and 4,29 causing an increase in hepatic fibrosis30 and resistance to antiviral therapy.31 This type of diabetes that follows liver cirrhosis is called hepatogenous diabetes and is regarded as a complication of this disease.32

The results of this study confirm that DM (either type 2 or hepatogenous DM) increases mortality of patients with liver cirrhosis and agree with those reported by 2 comparative prospective studies published.11,19 One of these studies reported a 5-year mortality in 51% of diabetic patients vs. 0% of non-diabetic patients.11 In the other study, the 3- and 5- year mortality was of 23.8% and 43.4% in diabetic patients vs 5.3% and 5.3% in non-diabetic patients.19 As in our study, the causes of death described in these studies were liver complications. This may be due to the fact that DM accelerates the progression of fibrosis and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma.33,34 It is important to note that in our study, mortality in diabetic patients (52% to 2.5 years of follow up) was significantly greater than that reported in the two aforementioned studies. In our patients, the causes of increased mortality may be due to: a) 100% of the patients had clinically overt DM in contrast to the 32.6% 11 and the 0%.19 of the patients in other studies (in the remaining patients DM was subclinical and it was only detected by OGTT); b) our patients had a higher proportion of cryptogenic etiology, 38.1 vs. 7% 11 and 0%19 in other reports; and c) the mean BMI of our patients was significantly higher than that observed in one of these studies where this parameter was evaluated: 28.2 ± 47 vs. 21.1 ± 2.5, respectively.19 These data suggest that most of our patients had type-2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Possibly patients with liver cirrhosis caused by type-2 DM and metabolic syndrome have a higher mortality than patients with cirrhosis of other causes as a result of microangiopathic complications induced by dyslipidemia, obesity and arterial hypertension.35 In this sense, 40% of our diabetic patients died of renal impairment. It is likely that these patients had more severe renal damage than non-diabetic patients, as they had significantly higher levels of serum creatinine. Also, hypercreatininemia was an independent predictor of mortality in multivariate regression analysis. Other studies have pointed to the hypercreatininemia as a predictor of mortality in patients with cirrhosis.36

The DM has been identified as an independent predictor of death in some studies.11,14,19 A 1-year survival probability of 52% was observed in a recent report of 75 patients with liver cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Advanced age, liver cancer, and DM -but not Child-Pugh score-were independent predictors of mortality at admission.37 In our study, DM, cryptogenic etiology of cirrhosis, blood creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL, and Child-Pugh score class C were significantly associated with death, whereas, female gender was a protective factor in univariate analysis; however, only serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL and Child-Pugh score class C were predictors of death in the multivariate analysis. In our study DM was not an independent predictor of death. Notwithstanding it is important to note that the follow up period of time in our study was shorter than the ones of the other studies in which DM has been found as a predictor of death. In these studies the mean follow up period of time was above 5 years.11,14,19 DM may be a long-term independent predictor of death in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis.

The mechanisms by which DM worsens the clinical course of liver cirrhosis have not been clearly established. Firstly, DM accelerates liver fibrosis and inflammation giving rise to more severe liver failure. Secondly, DM may enhance the incidence of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients which are associated with increased mortality.38,39

A limitation of our study was that subclinical DM (patients with normal fasting glucose levels and no history of DM in whom OGTT was suggestive of DM) and glucose intolerance were not searched by OGTT in patients classified as non-diabetic patients. The strength of our study is that we selected the mortality as main endpoint, which is a robust, objective parameter that is not subjected to bias.

In conclusion, in our study DM was associated with a significant increase in mortality of patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. Patients with DM had significantly higher cryptogenic etiology, anemia, renal impairment, hypoalbuminemia, CP score and BMI as compared to non-diabetic patients. Female gender, cryptogenic etiology, DM, serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL, and Child-Pugh score class C were significantly associated with mortality in univariate analysis, but only serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL and Child-Pugh score class C were independent predictors of death in multivariate analysis.