Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major and growing public health concern worldwide, including in Latin America. With more efficacious therapies becoming available, decision-makers will require accurate estimates of disease prevalence to assess the potential impact of new treatments. However, few estimates of the epidemiologic burden, either overall or by country, are available for Latin America; and the potential impact of currently-available treatments on the epidemiologic burden of HCV in Latin America has not been assessed. To address this, we systematically reviewed twenty-five articles presenting population-based estimates of HCV prevalence from general population or blood donor samples, and supplemented those with publically-available data, to estimate the total number of persons infected with HCV in Latin America at 7.8 million (2010). Of these, over 4.6 million would be expected to have genotype 1 chronic HCV, based on published data on the risk of progression to chronic disease and the HCV genotype distribution of Latin America. Finally, we calculated that between 1.6 and 2.3 million persons with genotype 1 chronic HCV would potentially benefit from current treatments, based on published estimates of genotypespecific treatment responsiveness. In conclusion, these estimates demonstrate the substantial present epidemiologic burden of HCV, and quantify the impending societal and clinical burden from untreated HCV in Latin America.

Up to 3% of the population-equaling approximately 170 million individuals-are estimated to be infected with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV), globally.1 It is a leading cause of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma,2,3 and is the underlying cause of over 475,000 deaths annually, worldwide.4 While mortality due to chronic HCV infection is an important facet for determining the impact on public health, one of the challenges in characterizing the epidemiology of HCV is that the infection is asymptomatic in up to 75% of individuals.5 New medical therapies are being developed which may be more effective in achieving a sustained viral response among treated patients with HCV. With these therapies coming to market, decision-makers have a pressing need for accurate estimates of disease prevalence, as well as estimates of those non-responsive to currently-available treatments, to understand the full economic impact of treating persons with HCV and plan the most effective use of resources.

Over recent years, some estimates of the epidemiologic burden of chronic HCV infection in Latin America have been published at the local and national level.6 However, no overall estimates of the epidemiologic burden for Latin America have been presented, and the burden in many of the countries in the area remains unexamined. This burden due to HCV would vary geographically, as it is based both on the availability of treatments, as well as the distribution of genotypes (a known predictor of treatment responsiveness).7 The recently published LATINO study showed that white Latinos with genotype 1 HCV were less likely to achieve a sustained viral response with current therapy (34%), compared to non-Latinos with genotype 1 HCV (49%; p < 0.001).8 This finding could have major public health implications, as most Latin Americans infected with HCV-from 65 to 75%-9-12 are infected with genotype 1; how these factors may impact the overall epidemiologic burden is unknown. The objectives of this study were to synthesize data on HCV prevalence, estimate the current country-specific number of cases, and assess the potential impact of currently-available treatments on the epidemiologic burden of HCV in Latin America.

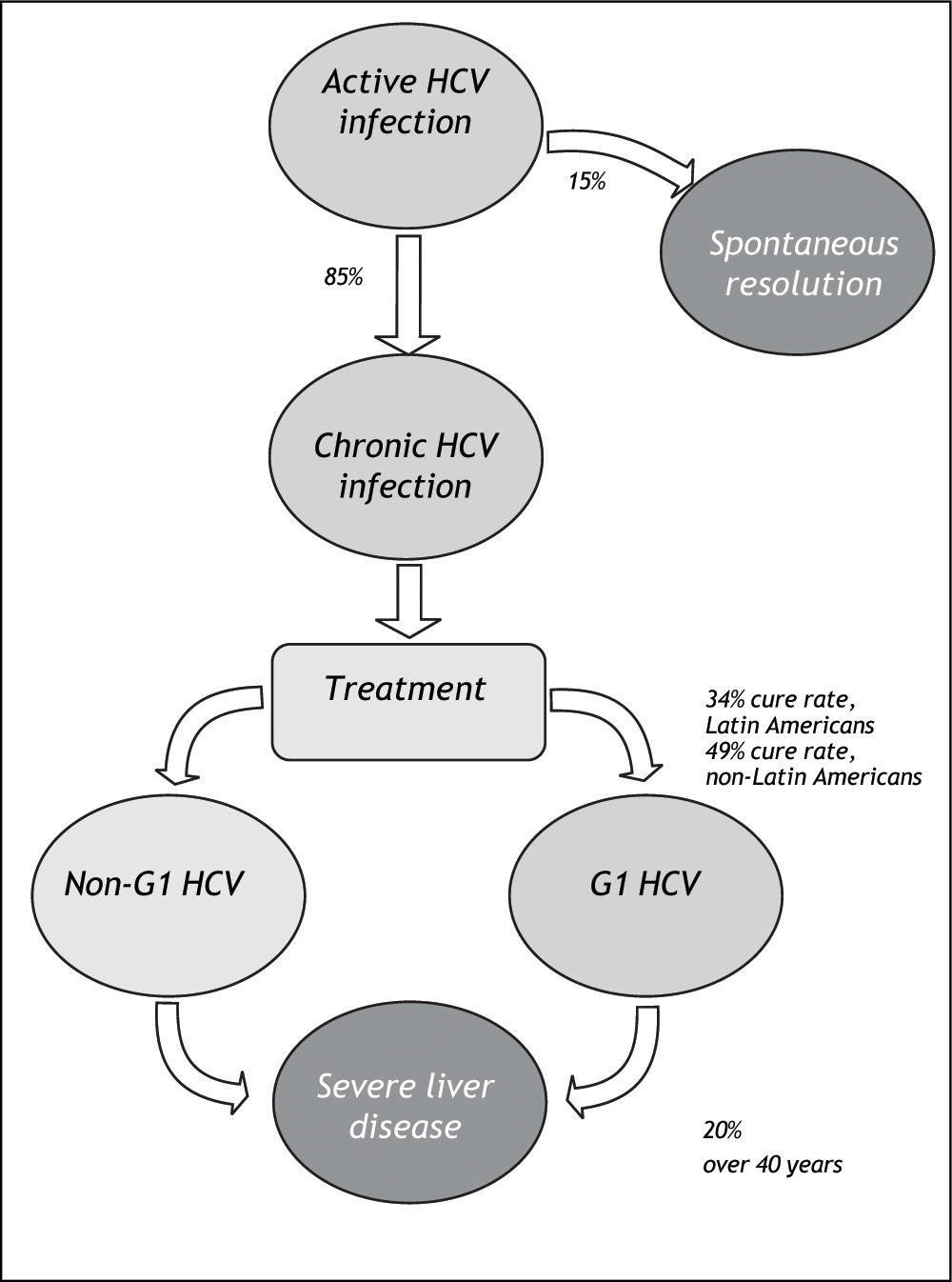

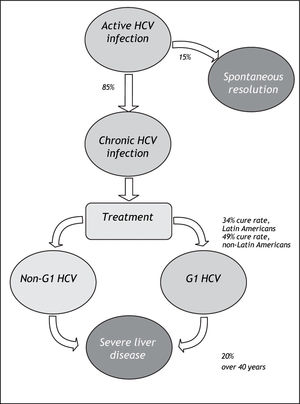

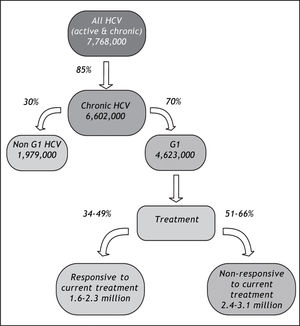

Material And MethodsWe systematically reviewed the published literature to synthesize country-specific estimates of the epidemiologic burden of HCV infection. These data were supplemented with data extracted through a review of published and publically available government reports, health agency websites, and national blood banks and surveillance networks. The number of cases potentially responsive to currently-available therapies was estimated by applying assumptions about genotype distribution and treatment responsiveness to the proportion of those infected with HCV who do not spontaneously resolve their HCV infection (Figure 1).

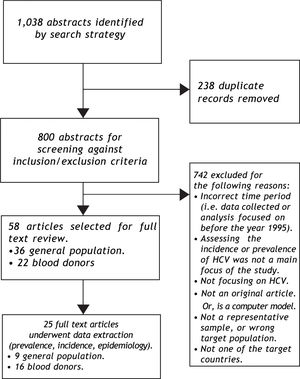

Systematic literature reviewThe systematic search was conducted of the Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane databases using customized terms to identify epidemiologic burden (incidence, prevalence, epidemiology) and hepatitis infection (by disease keywords: hepatitis, HCV and genotype). The search was performed in June 2011 for original studies published after January 1995. Searches were implemented for each country (Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, or Venezuela) independently, as well as overall for Latin, Central and South America. The search strategy is provided in Appendix 1. Individual Caribbean countries were not included due to a paucity of data identified that were specific to those on preliminary searching.

Published, peer-reviewed studies of the epidemiologic burden of HCV from representative samples of the general population or blood donors, identified by the search strategy, were selected for inclusion and reviewed by two independent reviewers. Only estimates based on laboratory-confirmed HCV infection were included. We included blood donor estimates from any studies reporting on HCV prevalence among individuals submitting blood tests for voluntary donation, or for purposes of employment, health, or travel. This review was limited to English, Spanish, and Portuguese language articles; data were extracted from the latter by native speakers.

Data elements extracted from each study included: study descriptors, details of study design (sampling frame, sample size, study period), baseline population characteristics, data source, duration of follow up, and HCV rates.

Supplemental data reviewAdditionally, to supplement information on countries where published general population estimates do not exist, a comprehensive review of publically-available data was conducted to synthesize counts and rates of positive HCV tests from national blood bank and surveillance networks. These included:

- •

- •

Argentina. Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Infecciosas/Centro Nacional de Red de Laboratorios,15 Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica;16

- •

Brazil. Agencia Nacional de Vigilancia Sanitoaria (National Agency for Health Surveillance);17 Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação;18

- •

Mexico. Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (Mexican Social Security Institute);19 Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2007;20 Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2000.21

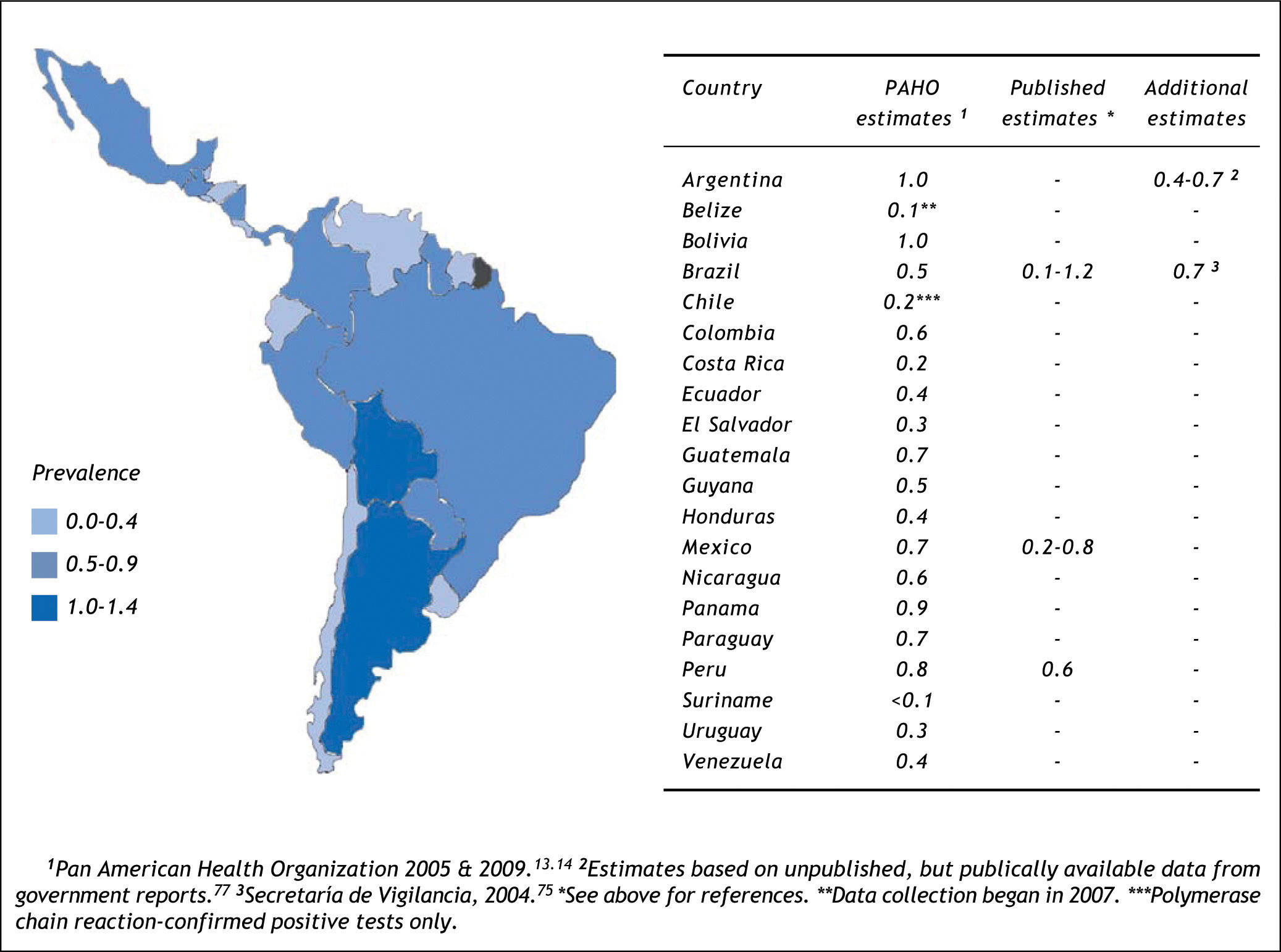

HCV prevalence estimates (%) from general population and blood donor samples were tabulated according to country. Estimates from blood donor and general population samples were compared, for countries where both estimates exist. Prevalence estimates were extrapolated to countries without prevalence data, using the midpoint of the grouped general population prevalence estimate. The number of persons infected with HCV was assessed by applying prevalence estimates to 2010 population projections for each of the countries included in the review. The potential impact of currently-available treatments on the epidemiologic burden was estimated by assuming that: 70% of Latin Americans with HCV infection are genotype 1;10,11 85% progress to chronic HCV;22 and 34% of those with chronic HCV attain sustained viral response with current pegylated-interferon plus ribavirin treatment. As a sensitivity analysis, the maximal rate of sustained viral response (49%) measured in the LATINO study was assumed.8

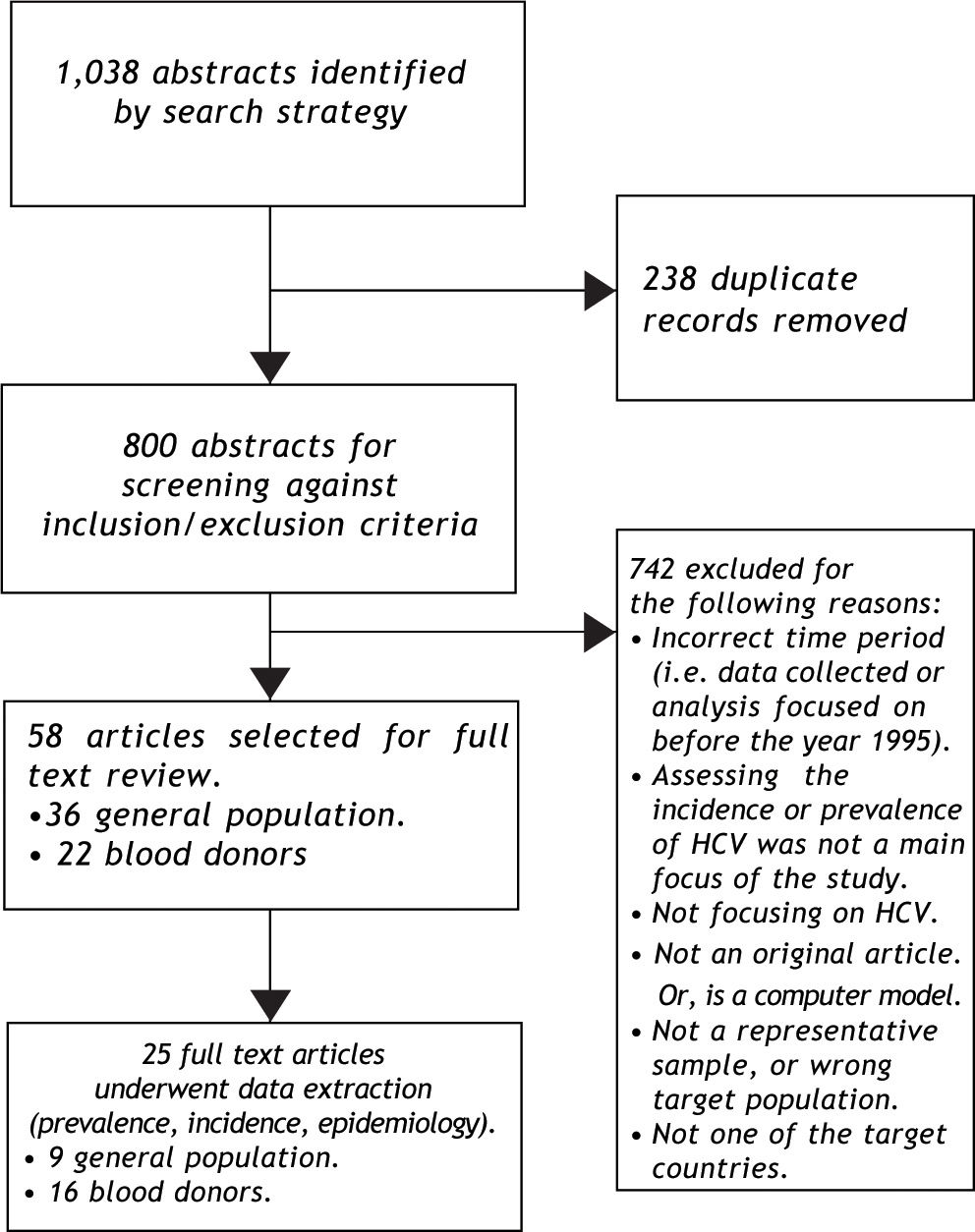

ResultsSynthesizing data on HCV prevalenceThe literature search was implemented as outlined in Figure 2. The search strategy identified nine population-based studies of HCV prevalence in Latin America; the supplemental review identified three additional estimates (Appendix 2). General population estimates of HCV prevalence from Latin America ranged from 0.923 to 5.8%.24 The Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica national surveillance system in Argentina estimated the national prevalence of HCV at between 1.3% and 1.7%,25 slightly higher than the results of a 2003 study from the province of Buenos Aires (0.9%).23 The Brazilian Ministério de Saude estimated the age-specific prevalence of HCV nationally at 0.9 to 1.9%,26,27 consistent with estimates from a large population-based study from Sao Paulo (1.4%).28 Other Brazilian estimates from population-based studies ranged from 1.5% (in Salvador)29 to 5.8% in Amazonian areas of high endemicity.24 The only available Chilean study reported a 1.230 prevalence estimate from a representative sample from Santiago. Mexican estimates ranged from 1.431 to 2.0%,32 and the former was based on the results of a large population-based national health survey (Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2000).31 No other estimates of HCV prevalence among general population samples from Latin America were identified.

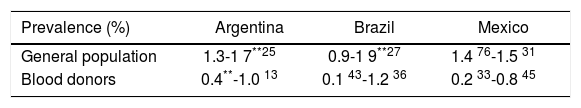

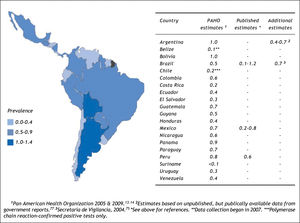

The search strategy also identified 16 studies reporting on HCV prevalence among representative samples of blood donors (Figure 3);19,33-47 in addition to the surveillance estimates reported by the PAHO.13,14 To assess the validity of using blood donor estimates in place of missing HCV general population prevalence estimates, we compared these using data from the Latin American countries where both types of estimates were available (Table 1). Using the midpoint of the grouped estimates (0.50.7%), based on data from Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, we found that relying on blood donor HCV prevalence estimates would underestimate the true prevalence of HCV infection by more than half.

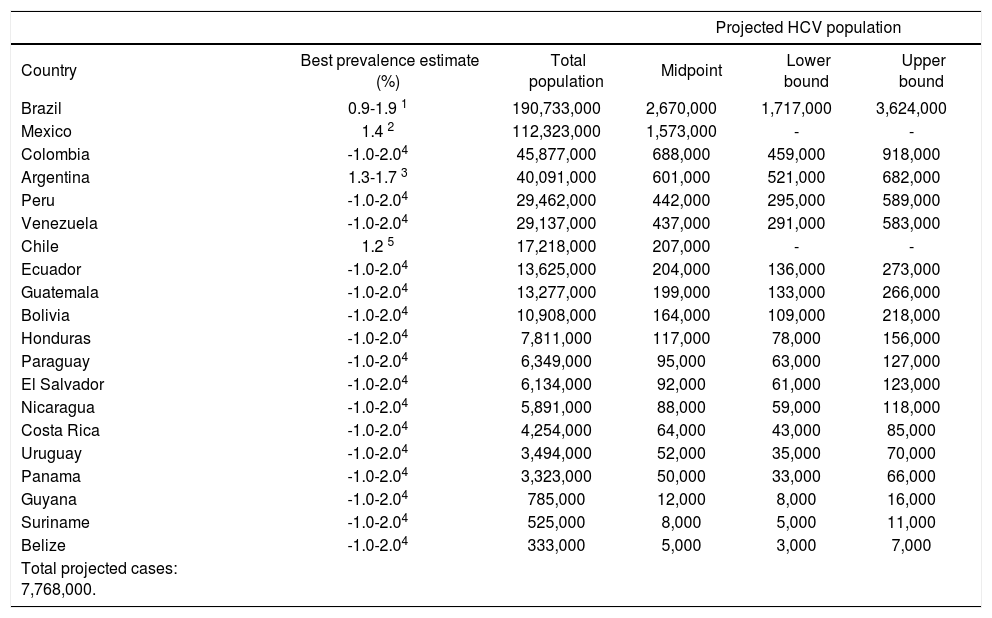

Estimating the country-specific number of casesHCV prevalence estimates from general population samples were used to estimate the country-specific number of cases (Table 2). Based on the best available evidence, the Chilean-(1.2%)30 and Mexican-(1.4%)31 specific values were used to estimate the prevalence of HCV for those two countries, and the midpoint of the ranges of unpublished national estimates for HCV prevalence for Argentina (1.5%)25 and Brazil (1.5%).26,27 Those 1.5% prevalence estimates were extrapolated for the remaining countries of Latin America.48 Using those prevalence values, the total population infected with HCV in Latin America in 2010 was estimated at 7.8 million persons (Table 2). The largest epidemiologic burden due to HCV is in Brazil (2.7 million persons infected) and Mexico (1.6 million persons infected), followed by Colombia (690,000 persons infected).

Projected number of persons infected with HCV in Latin America, 2010.

| Projected HCV population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Best prevalence estimate (%) | Total population | Midpoint | Lower bound | Upper bound |

| Brazil | 0.9-1.9 1 | 190,733,000 | 2,670,000 | 1,717,000 | 3,624,000 |

| Mexico | 1.4 2 | 112,323,000 | 1,573,000 | - | - |

| Colombia | -1.0-2.04 | 45,877,000 | 688,000 | 459,000 | 918,000 |

| Argentina | 1.3-1.7 3 | 40,091,000 | 601,000 | 521,000 | 682,000 |

| Peru | -1.0-2.04 | 29,462,000 | 442,000 | 295,000 | 589,000 |

| Venezuela | -1.0-2.04 | 29,137,000 | 437,000 | 291,000 | 583,000 |

| Chile | 1.2 5 | 17,218,000 | 207,000 | - | - |

| Ecuador | -1.0-2.04 | 13,625,000 | 204,000 | 136,000 | 273,000 |

| Guatemala | -1.0-2.04 | 13,277,000 | 199,000 | 133,000 | 266,000 |

| Bolivia | -1.0-2.04 | 10,908,000 | 164,000 | 109,000 | 218,000 |

| Honduras | -1.0-2.04 | 7,811,000 | 117,000 | 78,000 | 156,000 |

| Paraguay | -1.0-2.04 | 6,349,000 | 95,000 | 63,000 | 127,000 |

| El Salvador | -1.0-2.04 | 6,134,000 | 92,000 | 61,000 | 123,000 |

| Nicaragua | -1.0-2.04 | 5,891,000 | 88,000 | 59,000 | 118,000 |

| Costa Rica | -1.0-2.04 | 4,254,000 | 64,000 | 43,000 | 85,000 |

| Uruguay | -1.0-2.04 | 3,494,000 | 52,000 | 35,000 | 70,000 |

| Panama | -1.0-2.04 | 3,323,000 | 50,000 | 33,000 | 66,000 |

| Guyana | -1.0-2.04 | 785,000 | 12,000 | 8,000 | 16,000 |

| Suriname | -1.0-2.04 | 525,000 | 8,000 | 5,000 | 11,000 |

| Belize | -1.0-2.04 | 333,000 | 5,000 | 3,000 | 7,000 |

| Total projected cases: 7,768,000. | |||||

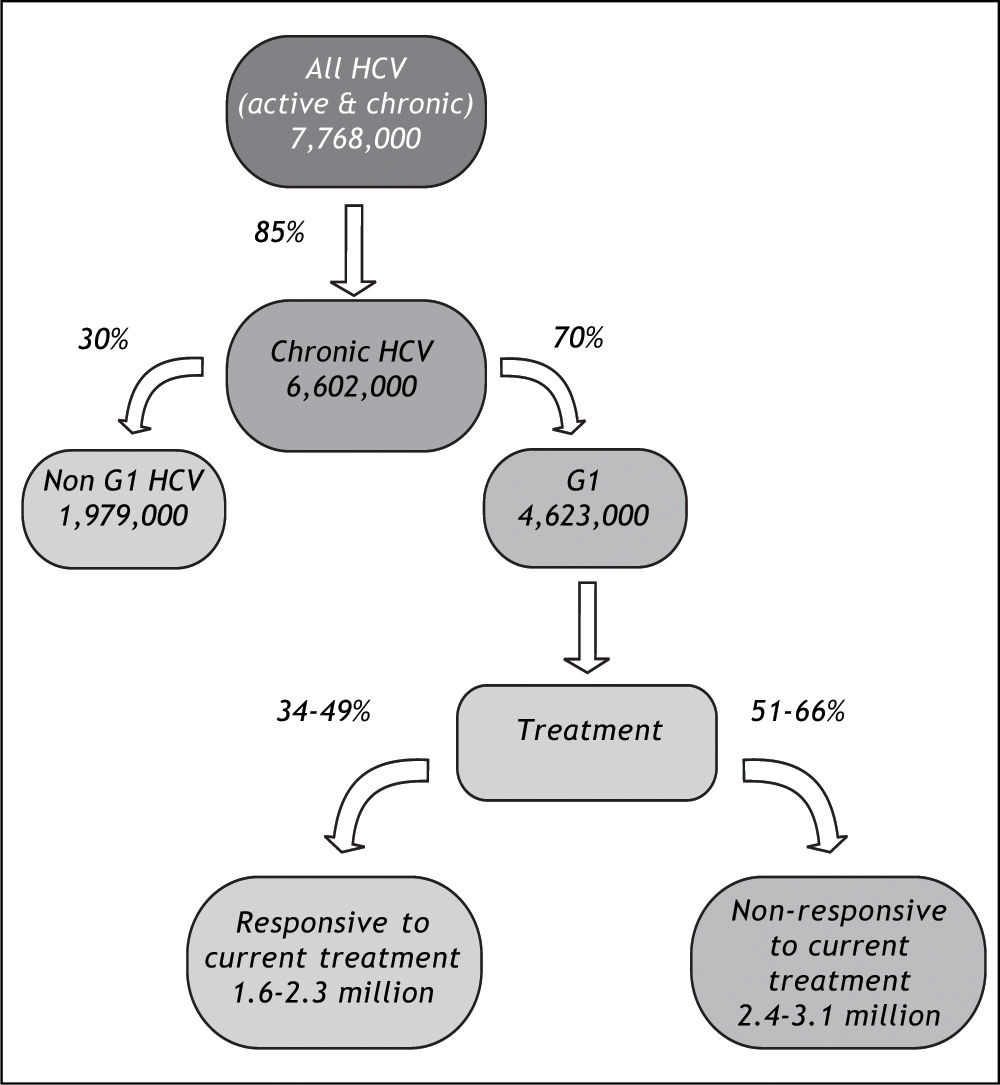

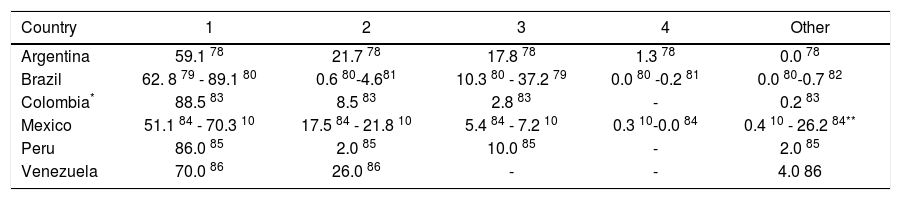

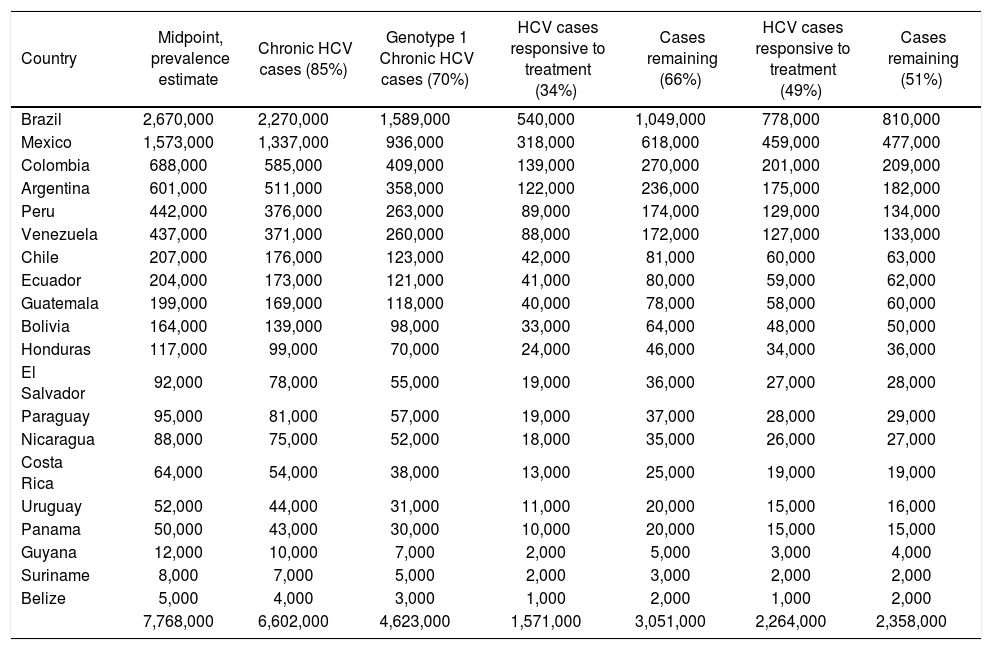

The potential impact of currently-available treatments on the epidemiologic burden was estimated by implementing assumptions regarding the prevalence of HCV genotype 1 in Latin America,10,11 rates of progression to chronic HCV,22 and Latin American-specific rates of treatment responsiveness for HCV genotype 1.8 Available data on genotype of infection from representative samples from the countries of Latin America are summarized in Table 3. As expected, the majority of studies found genotype 1 to be the most prevalent, and a large nationally-representative study from Mexico estimated this frequency at 70%.10 No estimates of the genotype distribution were identified for Belize, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, or Uruguay. Assuming that 85% of those infected progressed to chronic HCV infection,22 and that 70% of those have genotype 1 HCV,10,11 results in an estimated 4.6 million individuals in Latin America projected to have chronic HCV genotype 1 infection (Table 4).

Frequency (%) of HCV genotypes.

| Country | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 59.1 78 | 21.7 78 | 17.8 78 | 1.3 78 | 0.0 78 |

| Brazil | 62. 8 79 - 89.1 80 | 0.6 80-4.681 | 10.3 80 - 37.2 79 | 0.0 80 -0.2 81 | 0.0 80-0.7 82 |

| Colombia* | 88.5 83 | 8.5 83 | 2.8 83 | - | 0.2 83 |

| Mexico | 51.1 84 - 70.3 10 | 17.5 84 - 21.8 10 | 5.4 84 - 7.2 10 | 0.3 10-0.0 84 | 0.4 10 - 26.2 84** |

| Peru | 86.0 85 | 2.0 85 | 10.0 85 | - | 2.0 85 |

| Venezuela | 70.0 86 | 26.0 86 | - | - | 4.0 86 |

The impact of currently-available treatments on the epidemiologic burden.

| Country | Midpoint, prevalence estimate | Chronic HCV cases (85%) | Genotype 1 Chronic HCV cases (70%) | HCV cases responsive to treatment (34%) | Cases remaining (66%) | HCV cases responsive to treatment (49%) | Cases remaining (51%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 2,670,000 | 2,270,000 | 1,589,000 | 540,000 | 1,049,000 | 778,000 | 810,000 |

| Mexico | 1,573,000 | 1,337,000 | 936,000 | 318,000 | 618,000 | 459,000 | 477,000 |

| Colombia | 688,000 | 585,000 | 409,000 | 139,000 | 270,000 | 201,000 | 209,000 |

| Argentina | 601,000 | 511,000 | 358,000 | 122,000 | 236,000 | 175,000 | 182,000 |

| Peru | 442,000 | 376,000 | 263,000 | 89,000 | 174,000 | 129,000 | 134,000 |

| Venezuela | 437,000 | 371,000 | 260,000 | 88,000 | 172,000 | 127,000 | 133,000 |

| Chile | 207,000 | 176,000 | 123,000 | 42,000 | 81,000 | 60,000 | 63,000 |

| Ecuador | 204,000 | 173,000 | 121,000 | 41,000 | 80,000 | 59,000 | 62,000 |

| Guatemala | 199,000 | 169,000 | 118,000 | 40,000 | 78,000 | 58,000 | 60,000 |

| Bolivia | 164,000 | 139,000 | 98,000 | 33,000 | 64,000 | 48,000 | 50,000 |

| Honduras | 117,000 | 99,000 | 70,000 | 24,000 | 46,000 | 34,000 | 36,000 |

| El Salvador | 92,000 | 78,000 | 55,000 | 19,000 | 36,000 | 27,000 | 28,000 |

| Paraguay | 95,000 | 81,000 | 57,000 | 19,000 | 37,000 | 28,000 | 29,000 |

| Nicaragua | 88,000 | 75,000 | 52,000 | 18,000 | 35,000 | 26,000 | 27,000 |

| Costa Rica | 64,000 | 54,000 | 38,000 | 13,000 | 25,000 | 19,000 | 19,000 |

| Uruguay | 52,000 | 44,000 | 31,000 | 11,000 | 20,000 | 15,000 | 16,000 |

| Panama | 50,000 | 43,000 | 30,000 | 10,000 | 20,000 | 15,000 | 15,000 |

| Guyana | 12,000 | 10,000 | 7,000 | 2,000 | 5,000 | 3,000 | 4,000 |

| Suriname | 8,000 | 7,000 | 5,000 | 2,000 | 3,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 |

| Belize | 5,000 | 4,000 | 3,000 | 1,000 | 2,000 | 1,000 | 2,000 |

| 7,768,000 | 6,602,000 | 4,623,000 | 1,571,000 | 3,051,000 | 2,264,000 | 2,358,000 |

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

In the primary analysis, the rate of responsiveness measured among Latinos in the LATINO trial (34%) was assumed.8 Under this assumption, while more than 1.6 million individuals with chronic HCV genotype 1 would be expected to be responsive to currently-available treatments, an estimated 3.1 million would remain without a viable therapeutic option. Even when the maximal 49% responsiveness rate was assumed in sensitivity analysis,8 while 2.3 million individuals with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection in Latin America would be expected to be responsive to currently-available treatments, approximately 2.4 million would remain without a viable treatment option (Figure 4).

DiscussionDespite the World Health Organization citing a need to measure the epidemiologic burden of HCV in 2004,49 we found few robust epidemiologic data from Latin America. Using all available published estimates as well as unpublished data identified by an iterative comprehensive review, we projected the prevalence of chronic HCV infection in Latin America at over 6.6 million individuals. In absolute terms, the challenge is most acute in Brazil and Mexico, with over four million individuals infected with HCV in those two countries alone. Based on the distribution of genotype in the region, we estimated that while between 1.6 and 2.3 million individuals living with chronic HCV infection could potentially be responsive to currently-available treatments, an additional 2.4 to 3.1 million individuals infected would be non responsive. The estimates of the epidemiologic burden calculated here are broadly consistent with those from other investigators,50,51 as well as a recent review of the prevalence of HCV from selected countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.6 We extended upon the latter study's findings by synthesizing epidemiologic data for the entire region, estimating country-specific parameters, and assessing the potential impact of currently-available treatments on the present epidemiologic burden.

To help quantify the consequences of present HCV infections in Latin America, we synthesized data on the distribution of genotype of HCV infections in Latin America, as this is a known predictor of treatment responseiveness.7 As expected, genotype 1 was the predominant form of HCV infection in Latin America; most studies estimated the proportion of cases with genotype 1 HCV at between 65 and 75%.10,11 We then applied genotype 1-specific effectiveness rates associated with pegylated interferon with ribavirin, to quantify the potential impact of currently-available (and reimbursed) treatments48,52 on the epidemiologic burden of HCV in Latin America. The overall rates of sustained viral response after pegylated interferon and ribavirin range between approximately 35% and 50% for HCV genotype 1,8,53,54 however responsiveness may be lower for Latin Americans. While the LATINO study reported responsiveness rates of 49% among non-Latino whites and 34% among Latino whites with HCV genotype 1,8 other studies conducted among predominantly Latino populations have reported rates as low as 24%.55,56 Using the responsiveness rates from the LATINO study, we estimated that between 1.6 and 2.3 million individuals with HCV in Latin America could potentially benefit from currently-available treatments, although an additional 2.4 to 3.1 million individuals infected would remain without a viable treatment.

Understanding the epidemiologic, and attendant economic, burden of HCV is challenging, as infection is largely asymptomatic until late in the disease course for most individuals afflicted,5 and only a subset of patients progress to severe liver disease.22 The present economic burden of HCV is predominantly driven by treating identified cases to prevent severe liver disease, however, the future economic burden will include treating severe liver disease among those who have progressed. In Canada and the United States, an exponential increase in the incidence of severe liver disease over the next two decades has been predicted; and the same for the attendant economic burden of HCV.57,58 While no robust economic data are available for Latin America, the situation is likely even more grave, given the high rates of comorbid metabolic disease which would make achieving a sustained viral response among those with HCV difficult.59

Despite there being few data to assess the future burden of present HCV infections,9,58 there are some clues by which this may be imputed. While injection drug use is now the primary risk factor for acquiring HCV,60 transfusion prior to the widespread testing of the blood supply in the mid-1990s remains the primary known risk factor for most Latin Americans already infected.61,62 Indeed, studies from Brazil and Argentina have suggested transfusions to be causative in about one third of those patients,6,23,63 and one half to three quarters of those infected in Mexico and Chile.30,64,65 Such individuals would have become infected with HCV up to 20 years ago, and would therefore be at higher risk of progression to severe liver disease. When we consider that at least 2.4 million Latin Americans are infected with genotype 1 HCV and would not be responsive to available treatments, and assuming that at least one third of these were infected by transfusion, would mean that there are approximately 800,000 infected individuals at risk of developing severe liver disease over the next few years. Exact estimates of the risk of progression to severe liver disease due to HCV infection are variable,55,64,66 and challenging to derive given that the exact time of infection is often unknown. However, as treatment for severe liver disease is costly-from $4,300 to $30,000 (USD, 2009) per year depending on severity-these individuals will contribute a substantial burden to the health care systems in the near future.67

This review and synthesis is useful for identifying where more information is needed. The lack of country-specific population-based prevalence data on HCV infection in Latin America limits precise estimates of the true HCV burden.49 Although HCV prevalence estimates from blood donors were readily available, these have limited utility as they underestimate the true prevalence of HCV. This is not unexpected, as blood donors tend to be healthier than other subgroups of the population68 and prescreening practices would eliminate potential donors at higher risk of HCV infection.69 Nonetheless, these data can serve as a basis for comparing subsequent measures obtained from similar populations and tested under the same conditions; and therefore are useful for determining epidemiologic trends to infection.

In this review, Mexico was the only Latin American country with published population-based estimates at the national level.31,70 In the absence of published national estimates, regional general population prevalence estimates were incorporated, but these estimates were variable;28,29,71-73 due both to the varying distribution of risk factors for HCV infection, but also due to differences in the design of the studies that reported them. We approximated the epidemiologic burden based on the midpoint of available estimates for countries where specific estimates were not available, and a similar strategy may be used to inform estimates for the Caribbean nations that were not included in the present review. While likely broadly reflective, these projections may under or overestimate the country-specific burden, depending on the risk factor composition of each country. Finally, genetic variation in interleukin-28b is also a known predictor of treatment responsiveness,74 and would also be expected to impact the epidemiologic burden of HCV in Latin America. The impact of interleukin-28b was not incorporated here, however, as beyond preliminary investigations among Latin Americans with European ancestry, little is known about the distribution of variants in Latin American populations.75

The absence of general-population based estimates for many Latin American countries, as well as the discrepancies between blood donor and generalpopulation estimates highlight the need for additional, methodologically-rigorous studies of the epidemiologic and clinical burden to inform decision-makers in Latin America. Nonetheless, the projections indicate that the current, and impending, epidemiologic, clinical, and likely economic burden of HCV infection in Latin America is substantial. We estimated that 7.8 million individuals in Latin America would be infected with HCV, 4.6 million with the genotype 1 form. Of these, between 1.6 and 2.3 million individuals could benefit from currently-available treatments, although the remaining 2.4 to 3.1 million individuals with HCV genotype 1 in Latin America would not presently have a viable treatment option. These estimates may be useful in quantifying the growing societal and clinical burden due to HCV infection, and to identify subgroups of the population that are potential targets for new treatments that include direct-acting antivirals and improved interferons.

Abbreviations• HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

Financial SupportThis article was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

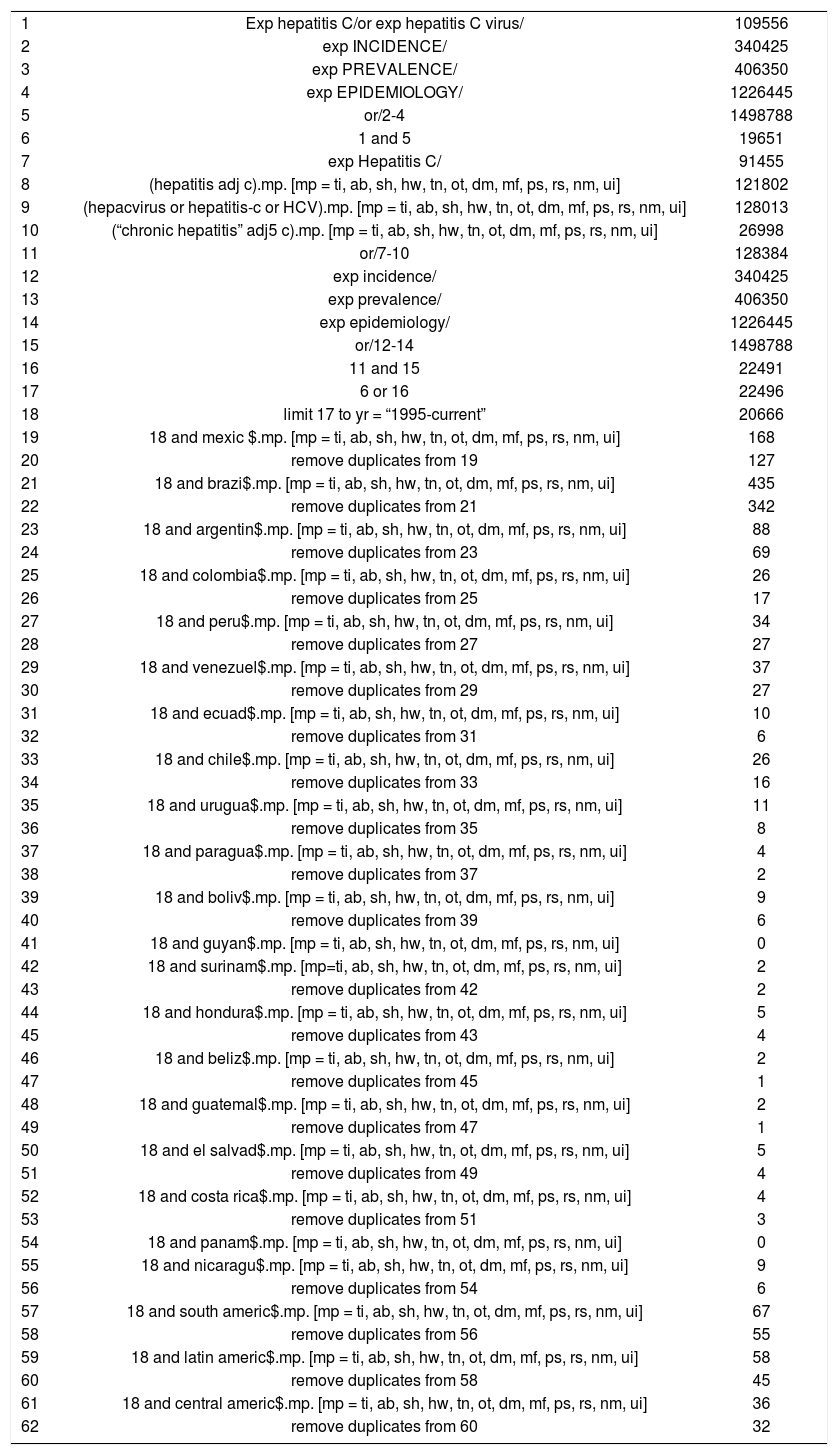

Search strategy.

| 1 | Exp hepatitis C/or exp hepatitis C virus/ | 109556 |

| 2 | exp INCIDENCE/ | 340425 |

| 3 | exp PREVALENCE/ | 406350 |

| 4 | exp EPIDEMIOLOGY/ | 1226445 |

| 5 | or/2-4 | 1498788 |

| 6 | 1 and 5 | 19651 |

| 7 | exp Hepatitis C/ | 91455 |

| 8 | (hepatitis adj c).mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 121802 |

| 9 | (hepacvirus or hepatitis-c or HCV).mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 128013 |

| 10 | (“chronic hepatitis” adj5 c).mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 26998 |

| 11 | or/7-10 | 128384 |

| 12 | exp incidence/ | 340425 |

| 13 | exp prevalence/ | 406350 |

| 14 | exp epidemiology/ | 1226445 |

| 15 | or/12-14 | 1498788 |

| 16 | 11 and 15 | 22491 |

| 17 | 6 or 16 | 22496 |

| 18 | limit 17 to yr = “1995-current” | 20666 |

| 19 | 18 and mexic $.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 168 |

| 20 | remove duplicates from 19 | 127 |

| 21 | 18 and brazi$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 435 |

| 22 | remove duplicates from 21 | 342 |

| 23 | 18 and argentin$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 88 |

| 24 | remove duplicates from 23 | 69 |

| 25 | 18 and colombia$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 26 |

| 26 | remove duplicates from 25 | 17 |

| 27 | 18 and peru$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 34 |

| 28 | remove duplicates from 27 | 27 |

| 29 | 18 and venezuel$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 37 |

| 30 | remove duplicates from 29 | 27 |

| 31 | 18 and ecuad$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 10 |

| 32 | remove duplicates from 31 | 6 |

| 33 | 18 and chile$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 26 |

| 34 | remove duplicates from 33 | 16 |

| 35 | 18 and urugua$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 11 |

| 36 | remove duplicates from 35 | 8 |

| 37 | 18 and paragua$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 4 |

| 38 | remove duplicates from 37 | 2 |

| 39 | 18 and boliv$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 9 |

| 40 | remove duplicates from 39 | 6 |

| 41 | 18 and guyan$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 0 |

| 42 | 18 and surinam$.mp. [mp=ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 2 |

| 43 | remove duplicates from 42 | 2 |

| 44 | 18 and hondura$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 5 |

| 45 | remove duplicates from 43 | 4 |

| 46 | 18 and beliz$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 2 |

| 47 | remove duplicates from 45 | 1 |

| 48 | 18 and guatemal$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 2 |

| 49 | remove duplicates from 47 | 1 |

| 50 | 18 and el salvad$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 5 |

| 51 | remove duplicates from 49 | 4 |

| 52 | 18 and costa rica$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 4 |

| 53 | remove duplicates from 51 | 3 |

| 54 | 18 and panam$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 0 |

| 55 | 18 and nicaragu$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 9 |

| 56 | remove duplicates from 54 | 6 |

| 57 | 18 and south americ$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 67 |

| 58 | remove duplicates from 56 | 55 |

| 59 | 18 and latin americ$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 58 |

| 60 | remove duplicates from 58 | 45 |

| 61 | 18 and central americ$.mp. [mp = ti, ab, sh, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, ps, rs, nm, ui] | 36 |

| 62 | remove duplicates from 60 | 32 |

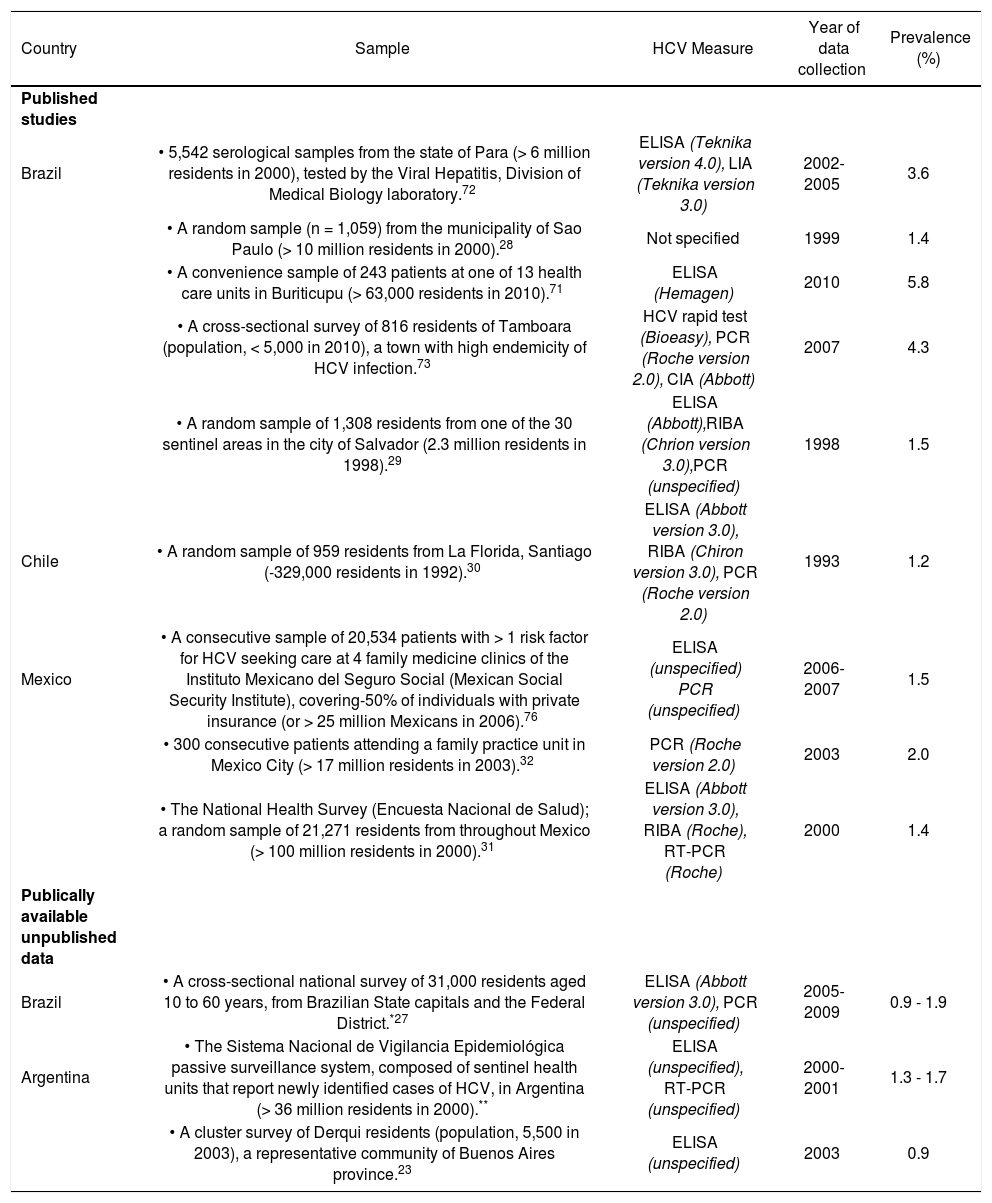

Estimates of the prevalence of HCV among adults from the general population.

| Country | Sample | HCV Measure | Year of data collection | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Published studies | ||||

| Brazil | • 5,542 serological samples from the state of Para (> 6 million residents in 2000), tested by the Viral Hepatitis, Division of Medical Biology laboratory.72 | ELISA (Teknika version 4.0), LIA (Teknika version 3.0) | 2002-2005 | 3.6 |

| • A random sample (n = 1,059) from the municipality of Sao Paulo (> 10 million residents in 2000).28 | Not specified | 1999 | 1.4 | |

| • A convenience sample of 243 patients at one of 13 health care units in Buriticupu (> 63,000 residents in 2010).71 | ELISA (Hemagen) | 2010 | 5.8 | |

| • A cross-sectional survey of 816 residents of Tamboara (population, < 5,000 in 2010), a town with high endemicity of HCV infection.73 | HCV rapid test (Bioeasy), PCR (Roche version 2.0), CIA (Abbott) | 2007 | 4.3 | |

| • A random sample of 1,308 residents from one of the 30 sentinel areas in the city of Salvador (2.3 million residents in 1998).29 | ELISA (Abbott),RIBA (Chrion version 3.0),PCR (unspecified) | 1998 | 1.5 | |

| Chile | • A random sample of 959 residents from La Florida, Santiago (-329,000 residents in 1992).30 | ELISA (Abbott version 3.0), RIBA (Chiron version 3.0), PCR (Roche version 2.0) | 1993 | 1.2 |

| Mexico | • A consecutive sample of 20,534 patients with > 1 risk factor for HCV seeking care at 4 family medicine clinics of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (Mexican Social Security Institute), covering-50% of individuals with private insurance (or > 25 million Mexicans in 2006).76 | ELISA (unspecified) PCR (unspecified) | 2006-2007 | 1.5 |

| • 300 consecutive patients attending a family practice unit in Mexico City (> 17 million residents in 2003).32 | PCR (Roche version 2.0) | 2003 | 2.0 | |

| • The National Health Survey (Encuesta Nacional de Salud); a random sample of 21,271 residents from throughout Mexico (> 100 million residents in 2000).31 | ELISA (Abbott version 3.0), RIBA (Roche), RT-PCR (Roche) | 2000 | 1.4 | |

| Publically available unpublished data | ||||

| Brazil | • A cross-sectional national survey of 31,000 residents aged 10 to 60 years, from Brazilian State capitals and the Federal District.*27 | ELISA (Abbott version 3.0), PCR (unspecified) | 2005-2009 | 0.9 - 1.9 |

| Argentina | • The Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica passive surveillance system, composed of sentinel health units that report newly identified cases of HCV, in Argentina (> 36 million residents in 2000).** | ELISA (unspecified), RT-PCR (unspecified) | 2000-2001 | 1.3 - 1.7 |

| • A cluster survey of Derqui residents (population, 5,500 in 2003), a representative community of Buenos Aires province.23 | ELISA (unspecified) | 2003 | 0.9 |

CIA: chemiluminescence immunoassay. ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. HCV: hepatitis C virus. LIA: line immunoassay. PCR: polymerase chain reaction. RT: reverse transcriptase. RIBA: recombinant immunoblot assay.

Methods published in Ximenes, 2010.26