Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) is a blood borne infection characterized by liver inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis that affects around 58 million people worldwide.[1–3] In 2019, 204,000 people were estimated to be living with HCV in Canada.[4] HCV is responsible for a high proportion of life-years lost compared to other infectious diseases and contributes to significant healthcare costs and resource burdens.[5], [6] In 2018, in alignment with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) goal of eliminating viral hepatitis as a global health threat by 2030,[7] the Government of Canada and many other nations set their own targets to progress towards HCV elimination on a national level.[8] Direct Acting Antivirals (DAAs) have been crucial in this effort towards HCV elimination.[9] With sustained virological response (SVR) rates exceeding 95%, DAAs are a highly efficacious and well-tolerated component of the current HCV care continuum.[7], [9] This is evidenced by the increase in cure rates in Canada from 2014 to 2018 as provinces gradually removed DAA coverage restrictions until they became universally accessible in 2018.[4], [5]

Despite substantial progress, many individuals still face barriers in accessing and adhering to HCV care and DAA treatment[5], [10], such as geographic location, socioeconomic challenges, health literacy, substance use, and stigma.[11–15] Furthermore, high risk populations including Indigenous populations, people who inject drugs (PWID), and gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men (gbMSM), remain disproportionally underserved and have suboptimal HCV treatment engagement.[16–19] Innovative models are required to reduce treatment burdens, optimize accessibility, and promote engagement across the HCV care continuum.[20]

Increasing evidence has shown telemedicine (TM) services to be an effective tool in the management of chronic infections.[21] TM provides an effective means to link underserved patients to specialty care and has been previously leveraged in Canada and other developed countries to increase access for rural and remote HCV populations.[13], [22] The current body of literature suggests that TM-services have helped achieve reduced wait times, increased treatment uptake and follow-up, decreased healthcare and patient costs, and high patient satisfaction.[23–26] The recent COVID-19 pandemic brought further attention to TM with STBBI-service providers expanding their remote care options and global experts highlighting the importance of TM in achieving HCV elimination efforts.[27], [28] Despite the potential of TM, rigorous studies of TM services used specifically for HCV care in Canada are limited justifying further research.[29], [30] This analysis aims to assess the effectiveness of TM access on the HCV care cascade before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Using The Ottawa Hospital Viral Hepatitis Program’s multidisciplinary HCV TM program, we evaluated the impact of TM access to HCV specialty service on HCV-infected patients’ outcomes and the potential impact on health equity.

2Patients and Methods2.1Patient populationThe Ottawa Hospital Viral Hepatitis Program (TOHVHP) provides specialty care to individuals located in Eastern Ontario, Western Quebec and Nunavut through multidisciplinary in-person clinics and by way of a telemedicine program. Ottawa, Canada is located in Eastern Ontario with a population of approximately one million. We conducted a retrospective cohort study of chronic HCV adult patients (≥18 years old with positive HCV RNA at least 6 months after acute infection) who had their first outpatient encounters with TOHVHP between October 2017 and March 2025. The corresponds to a period when DAAs where available and funding for treatment was in place. Patient information from patient charts and electronic medical records were collected in The Ottawa Hospital Viral Hepatitis Clinical Database (Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board 2004-196).

2.2HCV care delivery modelModels of delivery were categorized into three groups: standard in-patient clinic assessment only, TM only, and hybrid (HB) access. In advance of their first visit, patients were given a choice during appointment scheduling for their preferred mode of care (aside for specific scenarios in which in-person care was deemed necessary; chiefly those with advanced liver disease). The standard care patients received outpatient services exclusively at clinics located at The Ottawa Hospital–General Campus. The TM group patients exclusively engaged in virtual outpatient encounters using teleconference platforms or over the phone. The HB group patients engaged in both virtual and in-person clinic care. During COVID-19 pandemic, TM visit were encouraged by our appointment scheduling team during periods of heightened public health isolation measures. Support from TOHVHP’s multidisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, social work and pharmacists were available to all patients. Support and program referrals for individuals affected by substance use were part of standard of care.

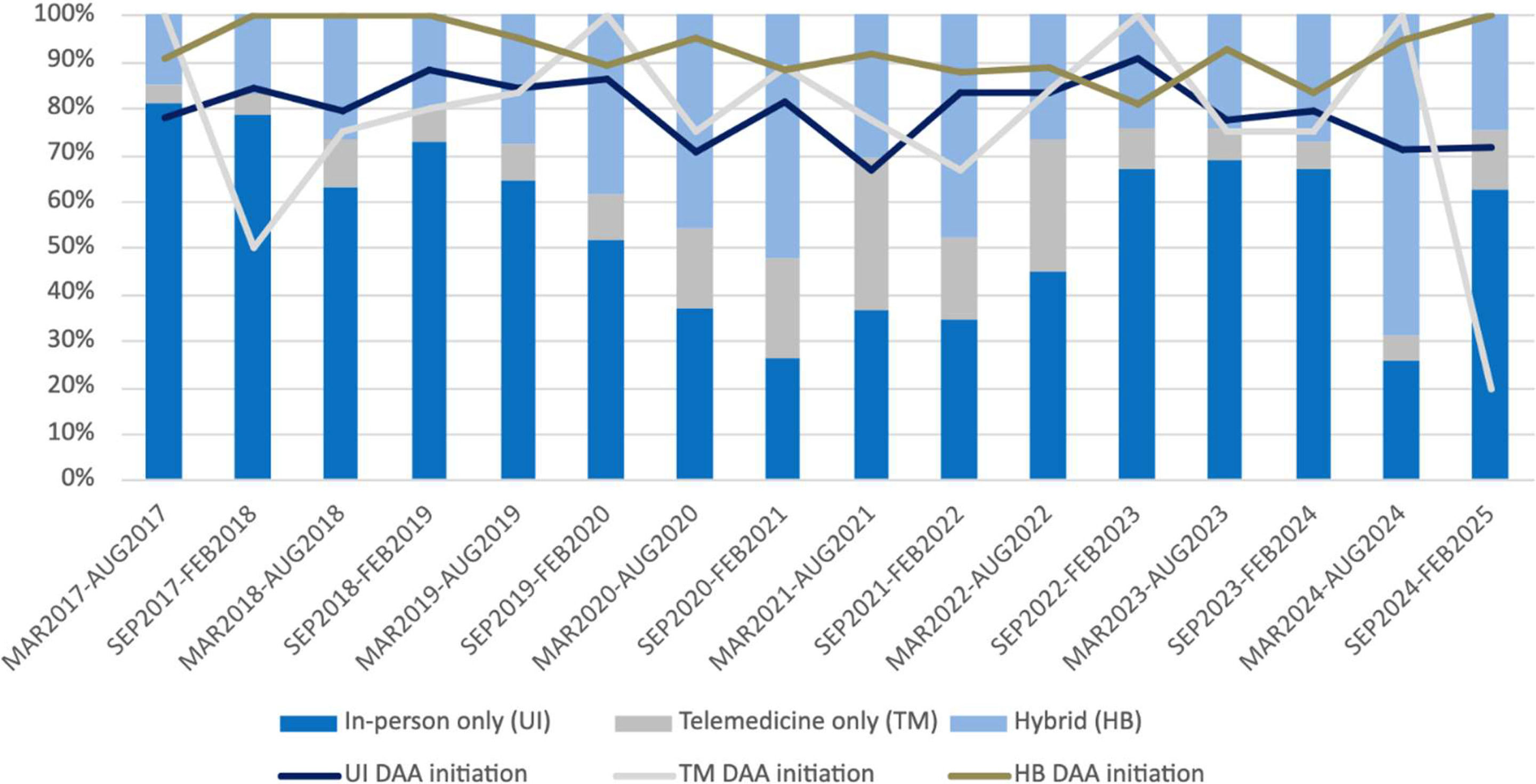

2.3Study variablesDemographic data was collected at baseline for eligible and consenting patients. This included age, sex, race, immigration status, education, employment, excess alcohol use, intravenous drug use (IDU), recreational drug use, incarceration history, psychiatric diagnosis history, and housing. Baseline laboratory results were also collected including HIV or hepatitis B virus (HBV) co-infection status, HCV RNA levels and genotype, AST, ALT, transient elastography score and fibrosis stage. Clinical outcomes of interest included HCV DAA treatment initiation and completion, SVR testing completion, and SVR. SVR outcomes included intent-to-treat (ITT) (defined as everyone who received a dose of DAA medication) and per protocol (defined as everyone who had SVR HCV RNA testing results). SVR was defined by HCV RNA negative results at least 4 weeks following completion of HCV antiviral therapy and was determined for each patient’s most recent treatment if they had completed multiple courses of HCV antiviral therapy. Patients with an expected treatment completion date on or after March 1, 2025, were excluded from DAA completion, SVR testing, and SVR analysis. Patients without available SVR bloodwork were labeled as ITT SVR negative but were excluded from per protocol SVR analysis. Patients with scheduled SVR bloodwork on or after March 1, 2025, were excluded from SVR testing and SVR analysis. Standard, TM, and HB care initiation and utilization rates were accessed in six-month intervals to evaluate the impact of dynamic COVID-19 public health policies and differences between the pre-, peri- and post-COVID pandemic outbreak periods. The pre-COVID pandemic interval was defined as the beginning of the study period until March 31, 2020, the peri-pandemic from April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2022 (the month during which the Ontario, Canada lockdown restrictions were lifted), and the post pandemic interval was defined as April 1, 2022 until the end of the study period.

2.4Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was conducted using SAS software v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA). All analyzed variables were determined a priori. Treatment initiation, completion, SVR testing and SVR proportions were calculated. Patients were considered lost to follow up if: (a) SVR bloodwork results were not available, (b) lost to follow-up from HCV care while on treatment. Chi-squared (χ2) tests or Fisher’s Exact Tests were conducted for categorical variables and T-tests for continuous variables. χ2 analysis was used to compare HCV care delivery groups in terms of treatment initiation, treatment completion, SVR testing and SVR outcome proportions. The pre-pandemic, peri-pandemic and pandemic periods were assessed. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine associations with DAA initiation and ITT SVR, including care delivery method, pandemic period, age, sex, and rurality.

2.5Ethical considerationsThe Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (OHSN-REB) has reviewed and granted approval to The Ottawa Hospital Viral Hepatitis Clinical Database (2004-196). Informed consent has been obtained from participants throughout the life of the study. Data has been anonymized before analysis.

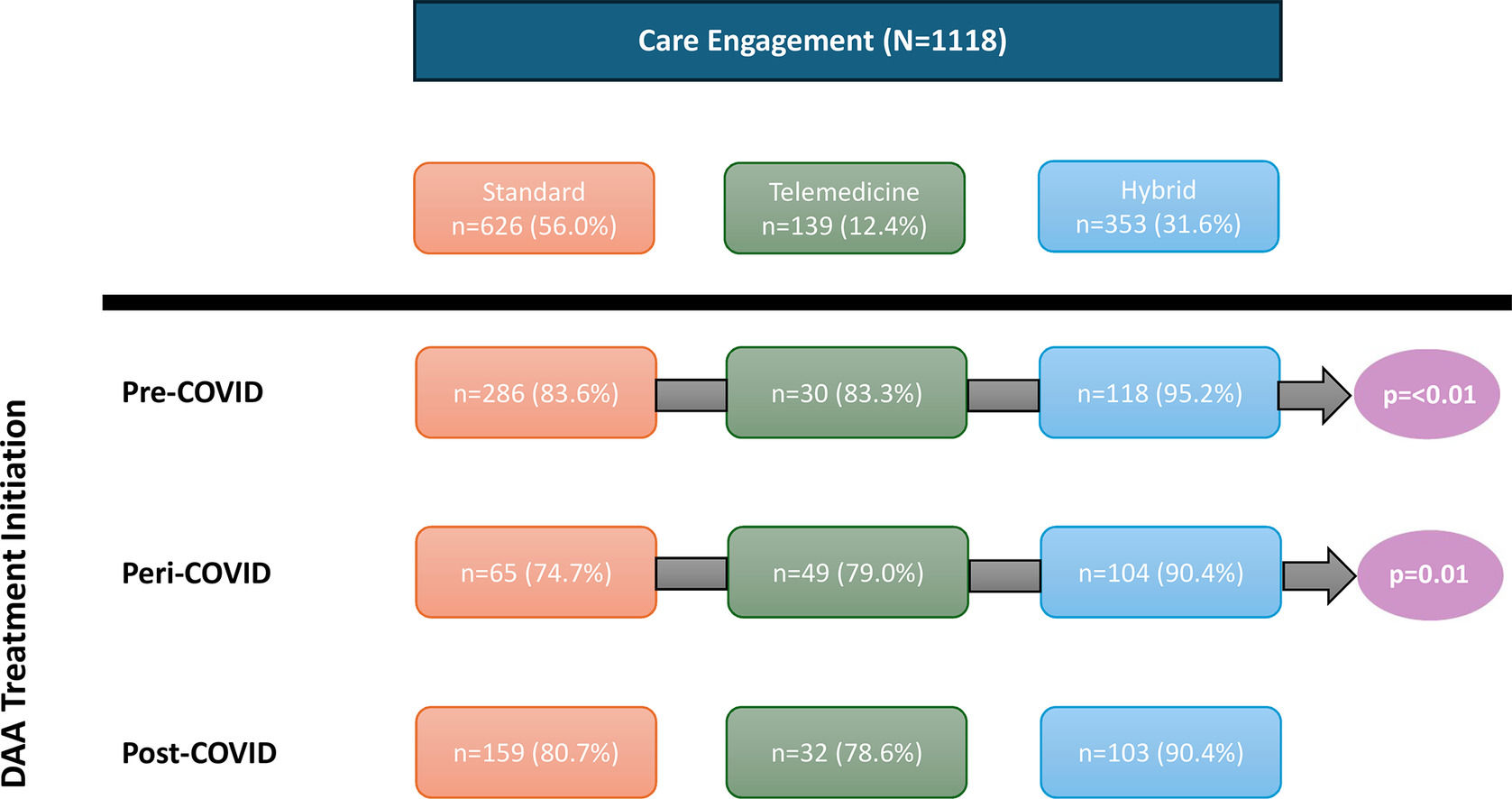

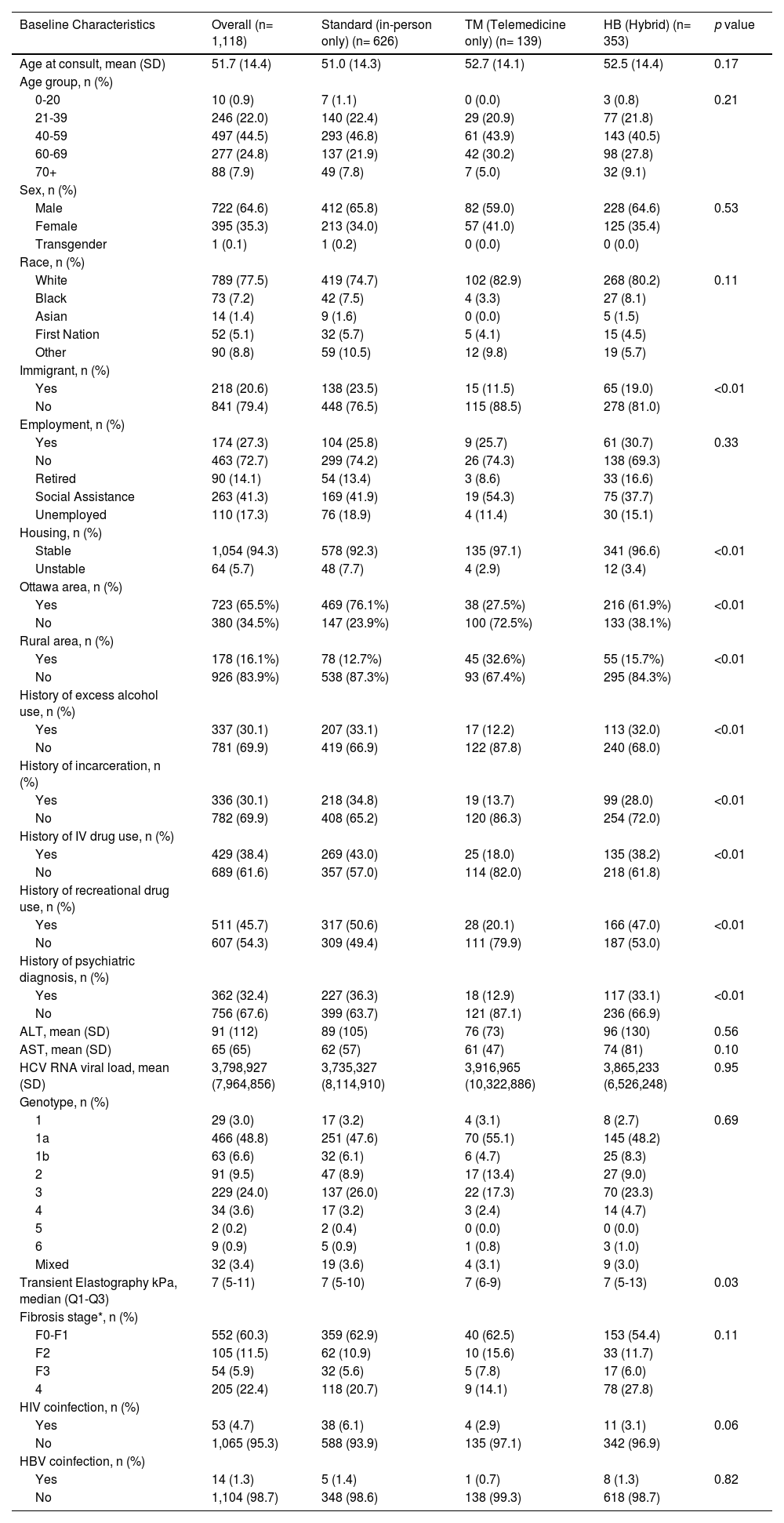

3Results3.1Study population characteristicsA total of 1,118 HCV-infected patients were evaluated during the study period, 945 (84.5%) of which initiated DAA treatment (Table 1). Among total patients, 626 (56.0%) received usual standard in-person care only, 139 (12.4%) received TM care only, and 353 (31.6%) received HB care. Of all patients managed by a HB approach, approximately 71% were initially assessed in clinic and 29% initially by TM. The proportion initially assessed by TM increased during the pandemic period (19% pre-pandemic, 56%- pandemic, 16% post-pandemic). The average age at first consult was similar across the three groups (standard: Mean (M) = 51.0 ± 14.3; TM: M = 52.7 ± 14.1; HB: 52.5 ± 14.4, p = 0.17). Sex and racial distributions were comparable across the three groups, with most patients being male (standard: 65.8%; TM: 59.0%; HB: 64.6%, p = 0.53) and identifying as White (standard: 74.7%; TM: 82.9%; HB: 80.2%, p = 0.11). Compared to the standard and HB groups, patients in the TM group were more likely to live outside Ottawa and less likely to be an immigrant, have a history of excess alcohol use, incarceration, IDU, recreational drug use, or a psychiatric condition. A lower proportion of patients in the TM and HB groups experienced housing instability compared to the standard care group (standard: 7.7%; TM: 2.9%; HB: 3.4%, p < 0.01). Baseline laboratory results were comparable in all three care model groups.

Baseline characteristics of patients by care delivery group.

| Baseline Characteristics | Overall (n= 1,118) | Standard (in-person only) (n= 626) | TM (Telemedicine only) (n= 139) | HB (Hybrid) (n= 353) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at consult, mean (SD) | 51.7 (14.4) | 51.0 (14.3) | 52.7 (14.1) | 52.5 (14.4) | 0.17 |

| Age group, n (%) | |||||

| 0-20 | 10 (0.9) | 7 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.8) | 0.21 |

| 21-39 | 246 (22.0) | 140 (22.4) | 29 (20.9) | 77 (21.8) | |

| 40-59 | 497 (44.5) | 293 (46.8) | 61 (43.9) | 143 (40.5) | |

| 60-69 | 277 (24.8) | 137 (21.9) | 42 (30.2) | 98 (27.8) | |

| 70+ | 88 (7.9) | 49 (7.8) | 7 (5.0) | 32 (9.1) | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 722 (64.6) | 412 (65.8) | 82 (59.0) | 228 (64.6) | 0.53 |

| Female | 395 (35.3) | 213 (34.0) | 57 (41.0) | 125 (35.4) | |

| Transgender | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White | 789 (77.5) | 419 (74.7) | 102 (82.9) | 268 (80.2) | 0.11 |

| Black | 73 (7.2) | 42 (7.5) | 4 (3.3) | 27 (8.1) | |

| Asian | 14 (1.4) | 9 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.5) | |

| First Nation | 52 (5.1) | 32 (5.7) | 5 (4.1) | 15 (4.5) | |

| Other | 90 (8.8) | 59 (10.5) | 12 (9.8) | 19 (5.7) | |

| Immigrant, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 218 (20.6) | 138 (23.5) | 15 (11.5) | 65 (19.0) | <0.01 |

| No | 841 (79.4) | 448 (76.5) | 115 (88.5) | 278 (81.0) | |

| Employment, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 174 (27.3) | 104 (25.8) | 9 (25.7) | 61 (30.7) | 0.33 |

| No | 463 (72.7) | 299 (74.2) | 26 (74.3) | 138 (69.3) | |

| Retired | 90 (14.1) | 54 (13.4) | 3 (8.6) | 33 (16.6) | |

| Social Assistance | 263 (41.3) | 169 (41.9) | 19 (54.3) | 75 (37.7) | |

| Unemployed | 110 (17.3) | 76 (18.9) | 4 (11.4) | 30 (15.1) | |

| Housing, n (%) | |||||

| Stable | 1,054 (94.3) | 578 (92.3) | 135 (97.1) | 341 (96.6) | <0.01 |

| Unstable | 64 (5.7) | 48 (7.7) | 4 (2.9) | 12 (3.4) | |

| Ottawa area, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 723 (65.5%) | 469 (76.1%) | 38 (27.5%) | 216 (61.9%) | <0.01 |

| No | 380 (34.5%) | 147 (23.9%) | 100 (72.5%) | 133 (38.1%) | |

| Rural area, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 178 (16.1%) | 78 (12.7%) | 45 (32.6%) | 55 (15.7%) | <0.01 |

| No | 926 (83.9%) | 538 (87.3%) | 93 (67.4%) | 295 (84.3%) | |

| History of excess alcohol use, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 337 (30.1) | 207 (33.1) | 17 (12.2) | 113 (32.0) | <0.01 |

| No | 781 (69.9) | 419 (66.9) | 122 (87.8) | 240 (68.0) | |

| History of incarceration, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 336 (30.1) | 218 (34.8) | 19 (13.7) | 99 (28.0) | <0.01 |

| No | 782 (69.9) | 408 (65.2) | 120 (86.3) | 254 (72.0) | |

| History of IV drug use, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 429 (38.4) | 269 (43.0) | 25 (18.0) | 135 (38.2) | <0.01 |

| No | 689 (61.6) | 357 (57.0) | 114 (82.0) | 218 (61.8) | |

| History of recreational drug use, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 511 (45.7) | 317 (50.6) | 28 (20.1) | 166 (47.0) | <0.01 |

| No | 607 (54.3) | 309 (49.4) | 111 (79.9) | 187 (53.0) | |

| History of psychiatric diagnosis, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 362 (32.4) | 227 (36.3) | 18 (12.9) | 117 (33.1) | <0.01 |

| No | 756 (67.6) | 399 (63.7) | 121 (87.1) | 236 (66.9) | |

| ALT, mean (SD) | 91 (112) | 89 (105) | 76 (73) | 96 (130) | 0.56 |

| AST, mean (SD) | 65 (65) | 62 (57) | 61 (47) | 74 (81) | 0.10 |

| HCV RNA viral load, mean (SD) | 3,798,927 (7,964,856) | 3,735,327 (8,114,910) | 3,916,965 (10,322,886) | 3,865,233 (6,526,248) | 0.95 |

| Genotype, n (%) | |||||

| 1 | 29 (3.0) | 17 (3.2) | 4 (3.1) | 8 (2.7) | 0.69 |

| 1a | 466 (48.8) | 251 (47.6) | 70 (55.1) | 145 (48.2) | |

| 1b | 63 (6.6) | 32 (6.1) | 6 (4.7) | 25 (8.3) | |

| 2 | 91 (9.5) | 47 (8.9) | 17 (13.4) | 27 (9.0) | |

| 3 | 229 (24.0) | 137 (26.0) | 22 (17.3) | 70 (23.3) | |

| 4 | 34 (3.6) | 17 (3.2) | 3 (2.4) | 14 (4.7) | |

| 5 | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 6 | 9 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.0) | |

| Mixed | 32 (3.4) | 19 (3.6) | 4 (3.1) | 9 (3.0) | |

| Transient Elastography kPa, median (Q1-Q3) | 7 (5-11) | 7 (5-10) | 7 (6-9) | 7 (5-13) | 0.03 |

| Fibrosis stage*, n (%) | |||||

| F0-F1 | 552 (60.3) | 359 (62.9) | 40 (62.5) | 153 (54.4) | 0.11 |

| F2 | 105 (11.5) | 62 (10.9) | 10 (15.6) | 33 (11.7) | |

| F3 | 54 (5.9) | 32 (5.6) | 5 (7.8) | 17 (6.0) | |

| 4 | 205 (22.4) | 118 (20.7) | 9 (14.1) | 78 (27.8) | |

| HIV coinfection, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 53 (4.7) | 38 (6.1) | 4 (2.9) | 11 (3.1) | 0.06 |

| No | 1,065 (95.3) | 588 (93.9) | 135 (97.1) | 342 (96.9) | |

| HBV coinfection, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 14 (1.3) | 5 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 8 (1.3) | 0.82 |

| No | 1,104 (98.7) | 348 (98.6) | 138 (99.3) | 618 (98.7) |

The proportion of patients utilizing standard care trended downward from the pre-pandemic to pandemic period and then trended upwards during the post-pandemic period (Figure 1). Conversely, the proportions of patients engaged in TM and HB were generally higher during time intervals during and immediately adjacent to the pandemic period. DAA treatment initiation proportions were generally high across all time intervals and care delivery groups. During the majority of time intervals, patients in the HB group had higher treatment initiation rates when compared to the standard and TM groups.

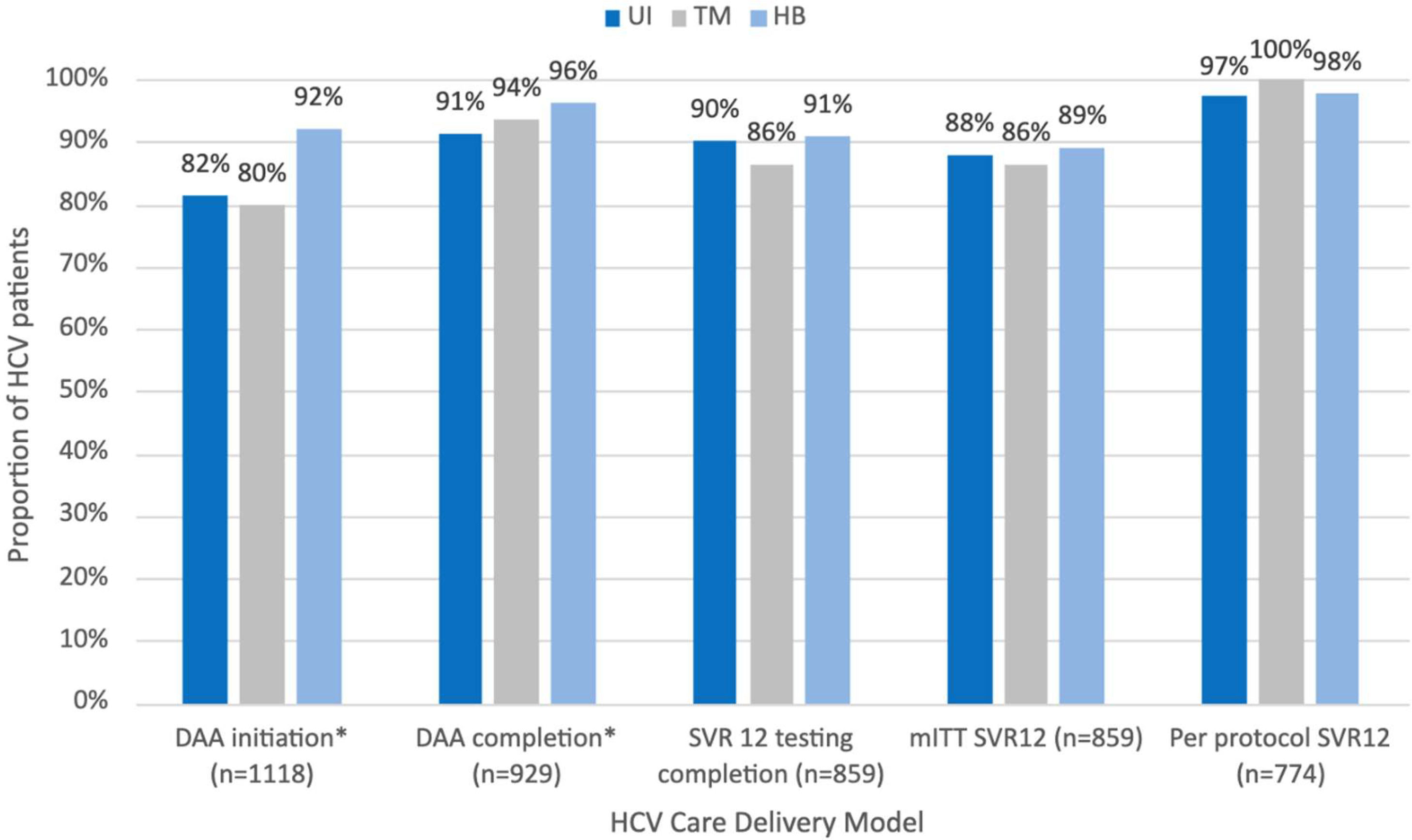

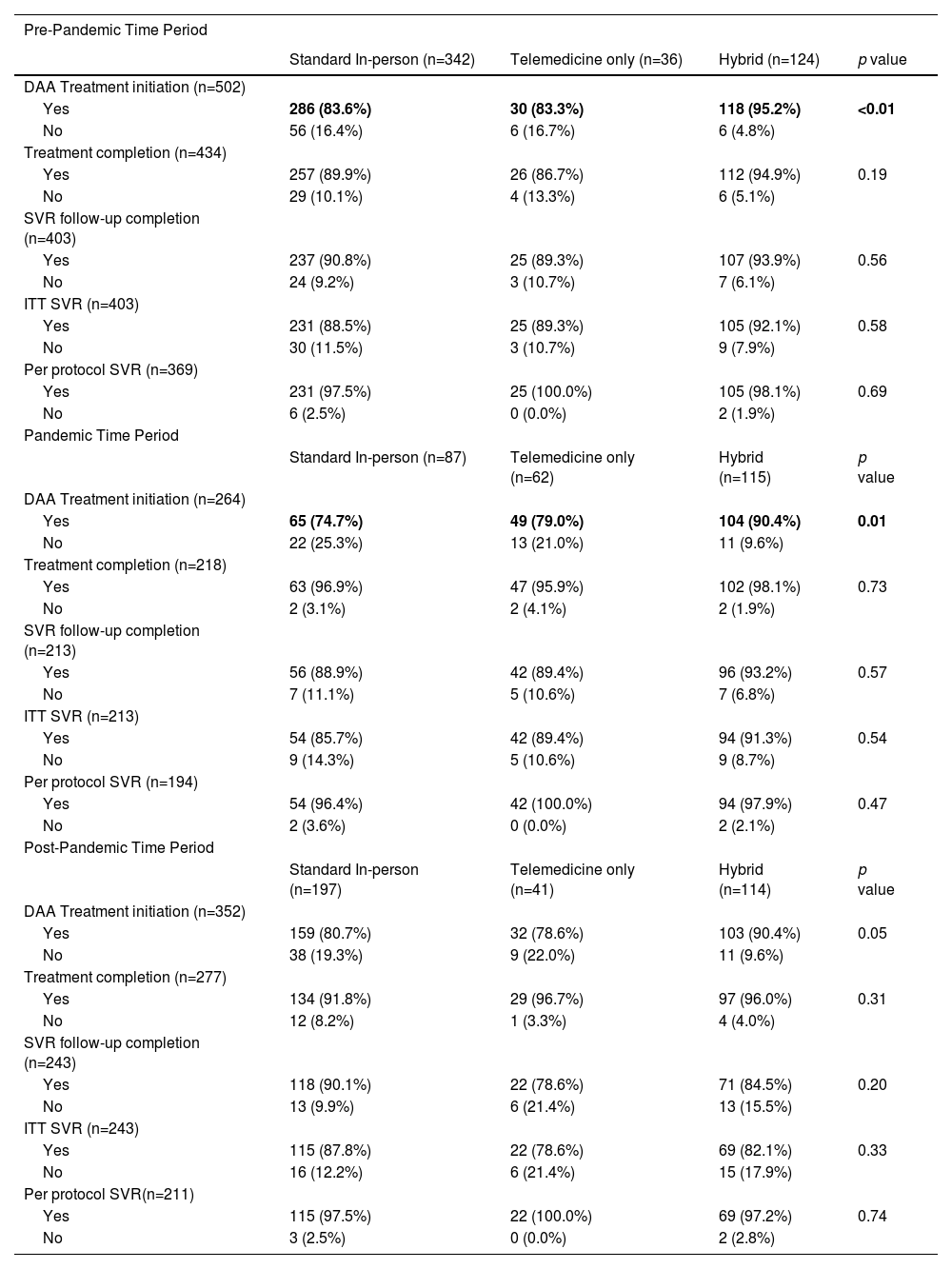

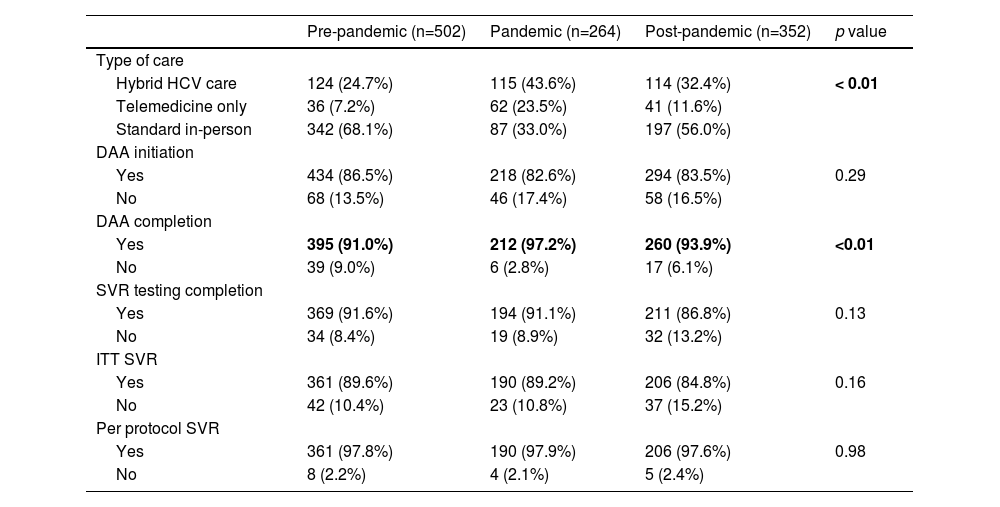

3.3Treatment outcomes by care delivery groupTreatment outcomes by care delivery group were assessed overall and by pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods (Figure 2, Table 2). In the overall cohort, patients engaging in HB care had higher proportions of DAA treatment initiation compared to patients engaging in standard and TM care (standard: 81.5%; TM: 79.1%; HB: 92.1%, p < 0.01) and completion (standard: 91.3%; TM: 93.6%; HB: 96.3%, p = 0.02). All other treatment outcomes, including SVR testing, ITT and per protocol SVR were similar between care delivery groups. Differences in treatment initiation are seen in the pre-, and pandemic periods, but not post-pandemic. No differences in treatment completion, and the rest of the outcomes were observed within each time period.

HCV Treatment Outcomes by Time Period

DAA= Direct Acting Antiviral; SVR= Sustained Virological Response; ITT= Intent-to-treat defined as receiving at least one dose of DAA medication; Per protocol defined as receiving DAA treatment and having post treatment SVR testing results available for analysis

We conducted a subanalysis of treatment outcomes by pandemic period on a restricted cohort of patient populations traditionally facing barriers to cure (IDU, incarceration experience, unemployed, immigrants, rural residents, or unstable housing) (Appendix Tables 1,2). DAA initiation, SVR testing completion, and ITT and per protocol SVR were similar across all time periods for both cohorts. A greater proportion of patients facing barriers to cure engaged in HB (pre: 23.5%; pandemic: 41.6%; post: 31.9%, p < 0.01) or TM care (pre: 6.3%; pandemic: 19.5%; post: 8.9%, p < 0.01) during the pandemic compared to the pre- and post-pandemic periods. Proportions of DAA completion for these patients (pre: 91.1%; pandemic: 98.1%; post: 95.8%, p < 0.01) were found to be higher during the pandemic compared to the pre- and post-pandemic periods. These observations were consistent with those of the overall population (Table 3).

Outcomes of all patients by time period.

DAA= Direct Acting Antiviral; SVR= Sustained Virological Response; ITT= Intent-to-treat defined as receiving at least one dose of DAA medication; Per protocol defined as receiving DAA treatment and having post treatment SVR testing results available for analysis

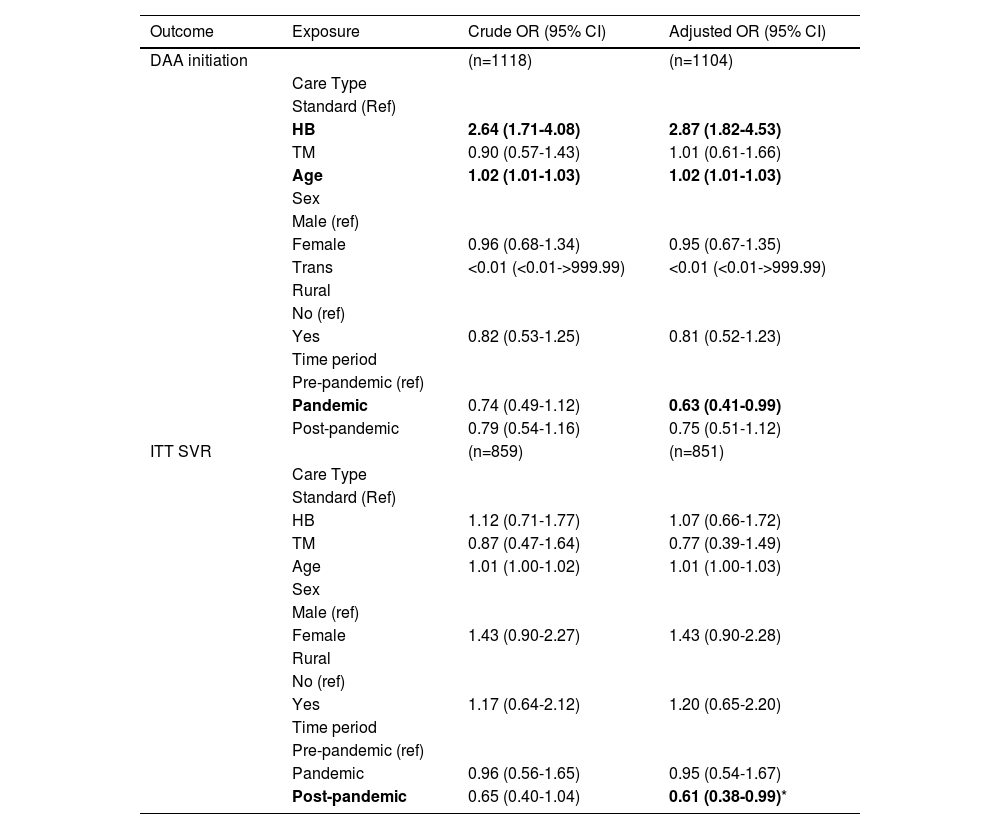

After adjusting for key variables including age, gender, rural habitation and pandemic period, HB care was associated with an increased odds of DAA initiation (OR = 2.87; 95% CI 1.82 to 4.53). This effect was also observed when restricting the analysis to patient populations facing key barriers to cure (OR = 2.35; 95% CI 1.35 to 4.07). In the overall cohort, the pandemic period was associated with decreased odds of DAA initiation (OR = 0.63; 95% CI 0.41 to 0.99), and the post-pandemic period was associated with decreased odds of ITT SVR (OR = 0.61; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.99), in comparison to the pre-pandemic period (Table 4). No associations were found between potential predictors of treatment outcomes and ITT SVR in patient populations facing barriers to cure (Appendix Table 2). Additional models assessing predictors of DAA treatment initiation were conducted including immigration status and history of injection drug use (data not reported). These variables were not found to be predictive of DAA initiation and did not alter the results reported in Table 4.

Odds ratios of care delivery type, pandemic time period and potential covariates for DAA initiation and ITT SVR.

| Outcome | Exposure | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAA initiation | (n=1118) | (n=1104) | |

| Care Type | |||

| Standard (Ref) | |||

| HB | 2.64 (1.71-4.08) | 2.87 (1.82-4.53) | |

| TM | 0.90 (0.57-1.43) | 1.01 (0.61-1.66) | |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male (ref) | |||

| Female | 0.96 (0.68-1.34) | 0.95 (0.67-1.35) | |

| Trans | <0.01 (<0.01->999.99) | <0.01 (<0.01->999.99) | |

| Rural | |||

| No (ref) | |||

| Yes | 0.82 (0.53-1.25) | 0.81 (0.52-1.23) | |

| Time period | |||

| Pre-pandemic (ref) | |||

| Pandemic | 0.74 (0.49-1.12) | 0.63 (0.41-0.99) | |

| Post-pandemic | 0.79 (0.54-1.16) | 0.75 (0.51-1.12) | |

| ITT SVR | (n=859) | (n=851) | |

| Care Type | |||

| Standard (Ref) | |||

| HB | 1.12 (0.71-1.77) | 1.07 (0.66-1.72) | |

| TM | 0.87 (0.47-1.64) | 0.77 (0.39-1.49) | |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 1.01 (1.00-1.03) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male (ref) | |||

| Female | 1.43 (0.90-2.27) | 1.43 (0.90-2.28) | |

| Rural | |||

| No (ref) | |||

| Yes | 1.17 (0.64-2.12) | 1.20 (0.65-2.20) | |

| Time period | |||

| Pre-pandemic (ref) | |||

| Pandemic | 0.96 (0.56-1.65) | 0.95 (0.54-1.67) | |

| Post-pandemic | 0.65 (0.40-1.04) | 0.61 (0.38-0.99)* |

DAA= Direct Acting Antiviral; SVR= Sustained Virological Response; ITT= Intent-to-treat defined as receiving at least one dose of DAA medication; Per protocol defined as receiving DAA treatment and having post treatment SVR testing results available for analysis

Indicates that odds of obtaining ITT SVR are lower post-pandemic than pre-pandemic. This is most likely due to the fact that patients in the post pandemic period have less of a timeframe to obtain SVR bloodwork and therefore would be labelled as ITT non-SVR. A model using per protocol SVR as the outcome measure does not demonstrate this effect (OR: 0.77 (0.25-2.44))

The increased availability of TM for the management of HCV in recent years has created opportunities to improve care access and engagement. Our findings demonstrate the capacity for TM to achieve favourable treatment outcomes and highlights strategies to address persistent gaps in HCV access and delivery. Engagement in care models varied by demographic and social factors. A greater proportion of patients based outside Ottawa engaged in TM compared to standard or HB care. This, in part, reflects challenges faced by rural patients when having to travel for in-person visits. These patterns are consistent with previous observations at our clinic .13 We observed a lower proportion of populations facing barriers to care engaging in TM compared to the overall population (Appendix 1, Table 3). This includes immigrants and those with histories of substance use, incarceration, and/or psychiatric conditions. TM generally favors patients with higher levels of socioeconomic stability and presents challenges for those without consistent access to technology or with lower digital health literacy.[31], [32] However, we do not believe that TM increases health inequality but rather provides more options to engage a highly heterogeneous population of people living with HCV. We believe that this observation is driven by the different demographics of rural versus urban based patients assessed in our viral hepatitis program. Rural-based viral hepatitis patients are less likely to be immigrants and less likely to have histories of injection drug use. They are also more likely to select telemedicine-based care given the long distances required to travel for in-patient clinics. Our urban-based patients are more likely to be immigrants and more like to have histories of injection drug use. Given that the distance to travel is shorter they are more likely to choice in-person visits. Many immigrants face language barriers. We find that visits are more successful when conducted in person in those facing language barriers. Our findings suggest that those with complex social determinants of health challenges may require more support than what TM alone can offer. Our overall findings demonstrate that TM and HB models of care can successfully engage and treat HCV for the majority of patients. This is consistent with existing literature indicating that TM can be an effective tool for HCV care.[13], [21], [22], [24–26], [33–35] Across all time periods, TM and HB care achieved treatment completion, follow-up and cure proportions comparable to standard care. A similar US-based analysis yielded comparable results.[34] These parallel findings reinforce the adaptability and potential of TM and HB models across geographic regions, health systems, and varying public health crisis policies.

Patients receiving HB care consistently achieved higher proportions of treatment initiation across all time periods compared to TM and standard care groups. Our adjusted models reinforced the positive association between HB care and treatment initiation. Greater treatment initiation in the HB group may be a consequence of the flexibility inherent to this care model. Through HB care, patients can benefit from the advantages of both in-person and virtual care while mitigating certain challenges associated with using either exclusively. Despite our observations that the pandemic was associated with a somewhat lower odds of DAA treatment initiation, we consistently observed high treatment initiation proportions during the pandemic period. This observation further suggests that HB models of care are more effective than TM or standard care alone during times of healthcare crisis or instability. Our findings suggest that combining TM with some level of periodic in-person care has the potential to help support complex care coordination and enhance HCV treatment outcomes. This may be particularly useful for patients with unstable access to technology.

In our cohort, including populations traditionally facing care barriers (IDU, incarceration experience, unemployed, unstable housing, rural residents and immigrants), the proportion completing treatment follow-up increased during the pandemic. During this period, a greater proportion of these patients were engaged in HB or TM care. This is a result of virtual HCV care expansion in response to pandemic policies[28], which allowed for greater access for all patients. Our findings suggest that even patients facing complex barriers to care can achieve high cure rates when successfully connected to virtual care options. This highlights the importance of establishing accessible TM and HB care models for these populations as underscored in previous research.[13], [22], [24], [33], [35] As HB and TM utilization declined post-pandemic we observed a decrease in treatment initiation. This raises important questions into the sustainability of virtual care progress made during the pandemic. TM and HB models should be seen as more than temporary health system solutions during times of crisis. We advocate for the sustained integration of virtual and HB models into HCV care infrastructure to promote long-term care access and health equity. The reasons for reduced utilization are multiple. Patient and physician-driven desire to return to ‘normal’ in-clinic evaluation likely contributed to this observation. Additional data, such as the findings reported in the present analysis, are valuable in demonstrating to health care providers and consumers that treatment outcomes can be similar, if not improved, by utilization of telemedicine-supported care. Limited physician reimbursement for TM services impacted a willingness to assess patients virtually. This critical issue must also be considered when attempting to sustain these models. In many jurisdictions including our own, health care providers receive minimal compensation for TM services delivered without an initial in-person visit which restricts the accessibility of virtual care.[36] Addressing reimbursement limitations in publicly and privately funded health care systems as well as pairing these models with increased social service supports such as housing, harm reduction, and mental health services could help further bridge treatment gaps and improve health outcomes for underserved populations.[37], [38]

We recognize limitations in our analysis. To some extent, patients self-selected their care delivery model rather than being randomized. This bias influenced the distribution of patients and demographic patterns found between groups. However, this did offer helpful insights into the advantages and limitations of each delivery model for serving different patient populations. We did not collect complete data on why some patients did not initiate DAA therapy. This limited our ability to analyze reasons and patterns for treatment non-initiation, particularly across pandemic periods. Missing sociodemographic data reduced the number of patients we could include in our multiple logistic regression analyses. This may have impeded identification of all associations. TOHVHP is a highly specialized and multidisciplinary clinic which may limit generalizability to other domestic and international regions where healthcare infrastructure differs. Although our clinic serves a diverse population of urban and rural-based individuals spread over two provinces and one territory, we acknowledge that study of additional regions will provide further insights into the role of TM-based models of care.

5ConclusionsWe observed that virtual care models can successfully deliver HCV specialty care and achieve treatment outcomes comparable to traditional in-person care. This was consistent before, during and after the pandemic. Our HB model of care was particularly effective in engaging populations facing traditional barriers to care and achieved successful treatment outcomes during times of healthcare disruption. We believe that expanding HB care models and improving the integration of social service supports are key in facilitating HCV elimination in Canada and elsewhere.

FundingNo external funding was used to fund this research.

Author ContributionsSF - conceptualization, writing - original draft, review & editing, HI - formal analysis, CC - conceptualization, supervision, writing - review & editing

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.