Aim. The objective of this study was to evaluate short- and long-term survival after surgical treatment between young and older hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients beyond the Milan criteria.

Material and methods. One hundred fifty-seven HCC patients (≤ 55 years old) were categorized into group A, and one hundred fifty-eight HCC patients (> 55 years old) were categorized into group B. Postoperative complications and overall survival were retrospectively analyzed.

Results. Older HCC patients had a higher rate of delayed extubation after surgery and suffered more complications after surgery, especially major complications. Intraoperative blood transfusion, liver fibrosis/cirrhosis and delayed extubation were risk factors related to postoperative complications. Microvascular invasion (MVI), tumor diameter, postoperative alpha-fetoprotein and the presence of satellites were independent risk factors for long-term survival. Young patients had more advanced tumors. Overall survival rates at 1, 3 and 5-years were 78.1%, 45.1% and 27.4% for young patients, respectively, and 86.5%, 57.5% and 42.4% for older patients, respectively (p = 0.007).

Conclusion. The category A group had poorer tumor characteristics and worse prognoses than the category B group.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third-leading cause of death worldwide. China accounts for approximately 55% of global HCC cases because of the high prevalence of HBV infection.1,2 Curative treatments for HCCs primarily include liver transplantation and liver resection. The Milan criteria, i.e., a single tumor ≤ 5 cm or three or fewer nodules ≤ 3 cm in diameter, was first used as standard criteria for liver transplantation due to satisfactory outcomes. In China, the majority of HCC patients are diagnosed at intermediate and advanced stages. Although the Milan criteria can be effectively and safely expanded for liver transplantations, the liver donor pool is small. Thus, most patients were alternatively treated with resections. Numerous studies have shown that HCC patients far exceeding the Milan criteria could benefit from surgical resections.3–5 These patients often have heavy tumor burdens and poor liver functions. Thus, the incidences of postoperative complications should not be overlooked. Previous studies have reported varying morbidity rates after hepatectomy in HCC patients from 9% to 51%.6,7 Understanding the incidence, severity and risk factors of complications for HCC patients exceeding the Milan criteria following resection is significant for making better decisions. Older age has been regarded as a high risk factor for surgical treatments and has been considered to be responsible for the high incidence of postoperative morbidity due to the high presence of co-morbid diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary diseases and diabetes. However, studies have shown that the morbidity rates of elderly patients were not different from those of younger patients.8 Other studies have reported lower postoperative morbidity rates in elderly HCC patients.9 Postoperative complication rates between young and older HCC patients exceeding the Milan criteria remain unclear.

Additionally, the impact of age on long-term survival remains unknown. Numerous studies have reported young patients achieving similar long-term survival as those of older patients.10–12 However, Chen, et al. revealed the survival of patients aged ≤ 40 years was better than that of patients aged > 40 years if the young HCC patients could survive more than 1 year.13 Other studies have suggested that age was not an independent prognostic factor when the tumor stages were the same.14 Recently, Yan, et al. reported that HBV genotype and integration may be distinct and increase risks in young HCC patients.15 Additionally, a few studies have suggested that age was a factor for HCC mortality for those 55-years-old or more.16–18 However, prognoses have not been well-investigated for HCCs exceeding the Milan criteria between patients aged > 55 years and patients aged ≤ 55 years.

In this study, we aimed to assess the incidence, severity and risk factors of complications between young (≤ 55-years-old) and old patients (> 55-years-old) exceeding the Milan criteria using the Clavien-Dindo classification. We sought to analyze the risk factors associated with longterm survival between both groups.

Material and MethodsPatientsThis study was endorsed by the Institutional Review Board of West China Hospital. Three hundred fifteen HCC patients exceeding the Milan criteria who were subjected to resection between December 2009 and July 2013 were included in our study. HCC was confirmed postoperatively via histopathological diagnoses by liver pathologists in West China Hospital. Microvascular invasion (MVI) and satellite nodes were detected by microscopy. Liver fibroses/cirrhosis were demonstrated by pathological examination (Ishak score = 5 or 6). The following exclusion criteria were used:

- •

Child C.

- •

Extrahepatic spread.

- •

Portal vein or hepatic vein invasion.

- •

Simultaneous malignancies.

One hundred fifty-seven HCC patients who were less than 55-years-old were categorized into group A, and 158 HCC patients who were more than 55-years-old were categorized into group B.

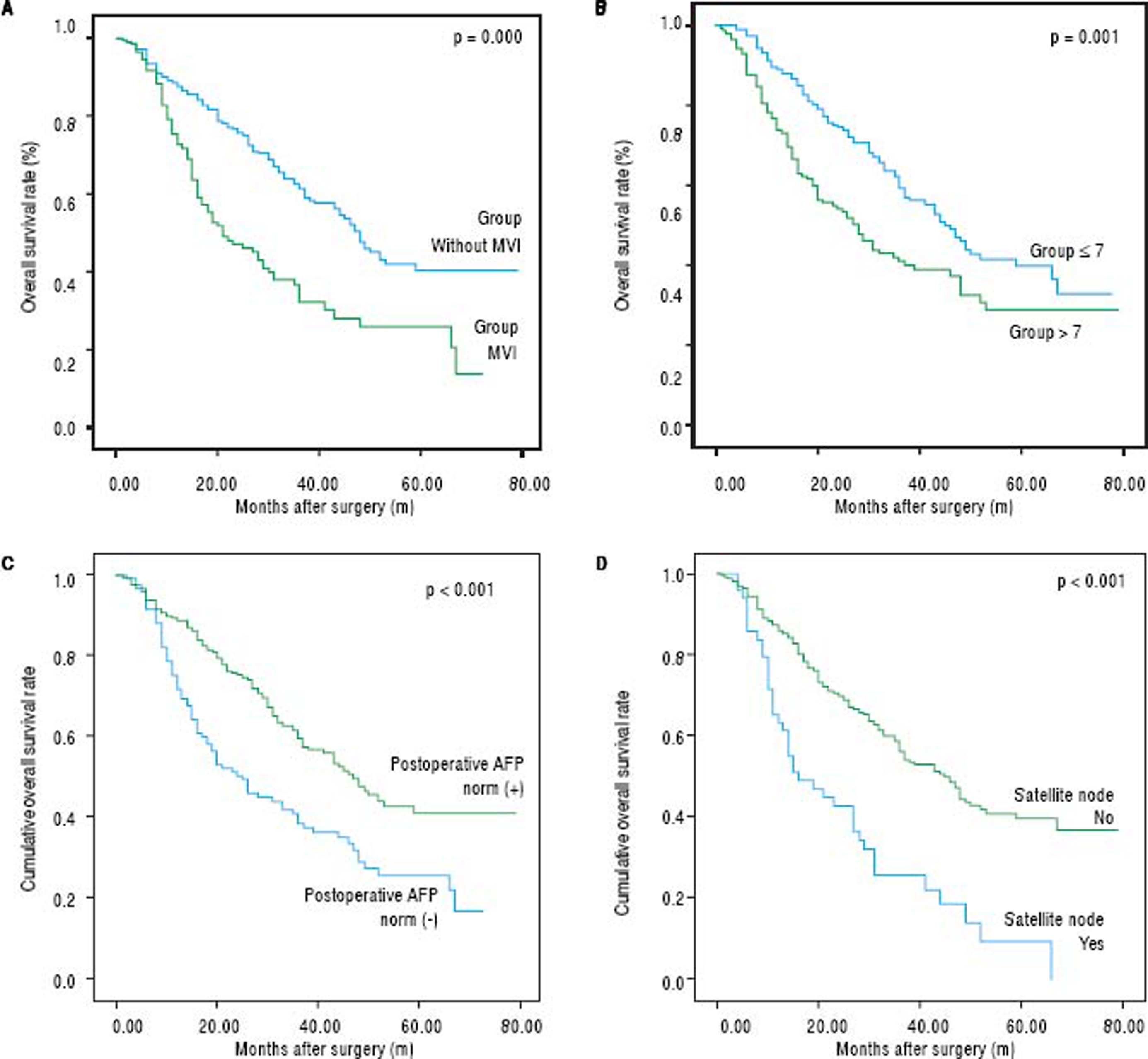

Follow-up and definitionsThe follow-up duration was calculated from the operation date to either the day of death or the day of last follow-up. The primary endpoints for this study were postoperative complications and overall survival. The median follow-up time was 32.0 mo ranging from 1 mo to 73 mo. The final follow-up evaluation was September 1, 2015. All patients were regularly followed every 3 months in the first 3 years and every 6 months in subsequent years. Liver function tests, blood tests, AFP concentration, HBV-DNA tests, ultrasonography, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging and chest radiography were regularly performed for all patients. When HCC recurrence was suspected, additional imaging tests (usually magnetic resonance imaging or computer tomography) were performed to check for recurrence. Postoperative HCC recurrence was considered present if either a lesion was identified measuring at least 2 cm with arterial hypervascularization, which was demonstrated by at least two imaging modalities, or a hypervascular nodule exceeding 2 cm was demonstrated in a single imaging study with AFP > 400 ng/mL. If recurrence was confirmed, treatment strategies were proposed based on the multidisciplinary team consisting of surgeons, pathologists and radiologists. Infectious complications in our study included pneumonia and urinary tract infections or infections requiring medical intervention. The Clavien-Dindo classification was applied to assess the severity of each complication.19 Delayed extubation was defined as the patient not being extubated at the end of the surgical case before leaving the operating room. Postoperative ascites was defined as abdominal outputs > 500 mL/d or ascites that required medical treatment to be controlled.20 Evaluation of postoperative AFP was conducted 12 weeks after surgery. Normalized AFP (norm+) was described as a postoperative AFP level ≤ 20 ng/mL. Non-normalized AFP (norm-) was defined as a postoperative AFP level > 20 ng/mL. Major complications included complications graded as Clavien-Dindo stage system III-V. The cutoff value of tumor diameter in figure 1B was defined as the mean tumor size in our study.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using SPSS20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows. All continuous variables were displayed as the means ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were analyzed using %2 or Fisher’s exact test. Independent risk factors for complication were identified by logistic regression. Independent risk factors for overall survival (OS) were identified by the stepwise-forward Cox regression model. Cumulative DFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between the curves were tested using the log-rank test. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

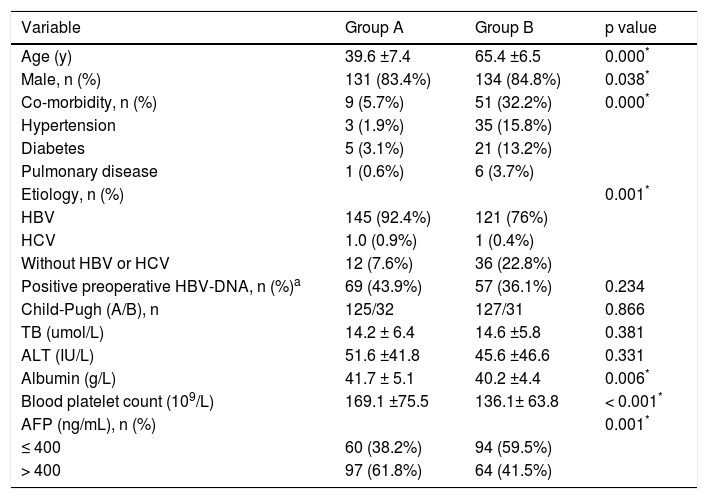

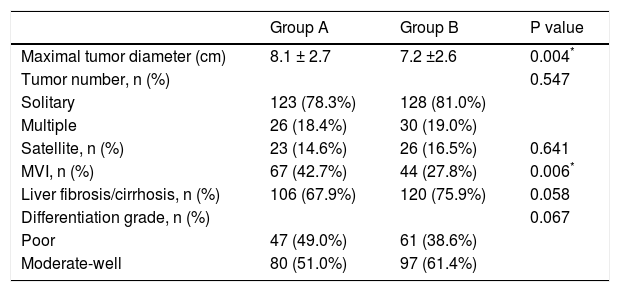

ResultsPatient clinical characteristicsThe clinical characteristics of both groups are shown in table 1. The mean ages of group A and group B were 39.6 and 65.4 years, respectively (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in the positive HBV-DNA loads or liver functions. Group A had higher levels of blood platelet counts and albumin (p < 0.001). Group B had a lower rate of hepatitis B infection (HBV) (p = 0.001) and a higher proportion of patients with co-morbid diseases (p < 0.05). Rates of patients with AFP > 400 ng/mL were higher in group A than in group B (62.3% vs. 41.5%, p < 0.05). As shown in table 2, tumor differentiation and the presence of satellites between groups A and B were not significant. However, the size of the largest tumor was significantly larger in group A than in group B. The mean tumor diameter was 8.1 cm for group A and 7.2 cm for group B (p = 0.004). Group A had a higher presence of MVI compared with group B (42.7% vs. 27.8%, p = 0.006).

Demographic data for group A and group B.

| Variable | Group A | Group B | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 39.6 ±7.4 | 65.4 ±6.5 | 0.000* |

| Male, n (%) | 131 (83.4%) | 134 (84.8%) | 0.038* |

| Co-morbidity, n (%) | 9 (5.7%) | 51 (32.2%) | 0.000* |

| Hypertension | 3 (1.9%) | 35 (15.8%) | |

| Diabetes | 5 (3.1%) | 21 (13.2%) | |

| Pulmonary disease | 1 (0.6%) | 6 (3.7%) | |

| Etiology, n (%) | 0.001* | ||

| HBV | 145 (92.4%) | 121 (76%) | |

| HCV | 1.0 (0.9%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Without HBV or HCV | 12 (7.6%) | 36 (22.8%) | |

| Positive preoperative HBV-DNA, n (%)a | 69 (43.9%) | 57 (36.1%) | 0.234 |

| Child-Pugh (A/B), n | 125/32 | 127/31 | 0.866 |

| TB (umol/L) | 14.2 ± 6.4 | 14.6 ±5.8 | 0.381 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 51.6 ±41.8 | 45.6 ±46.6 | 0.331 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 41.7 ± 5.1 | 40.2 ±4.4 | 0.006* |

| Blood platelet count (109/L) | 169.1 ±75.5 | 136.1± 63.8 | < 0.001* |

| AFP (ng/mL), n (%) | 0.001* | ||

| ≤ 400 | 60 (38.2%) | 94 (59.5%) | |

| > 400 | 97 (61.8%) | 64 (41.5%) |

Pathological features between both groups.

| Group A | Group B | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal tumor diameter (cm) | 8.1 ± 2.7 | 7.2 ±2.6 | 0.004* |

| Tumor number, n (%) | 0.547 | ||

| Solitary | 123 (78.3%) | 128 (81.0%) | |

| Multiple | 26 (18.4%) | 30 (19.0%) | |

| Satellite, n (%) | 23 (14.6%) | 26 (16.5%) | 0.641 |

| MVI, n (%) | 67 (42.7%) | 44 (27.8%) | 0.006* |

| Liver fibrosis/cirrhosis, n (%) | 106 (67.9%) | 120 (75.9%) | 0.058 |

| Differentiation grade, n (%) | 0.067 | ||

| Poor | 47 (49.0%) | 61 (38.6%) | |

| Moderate-well | 80 (51.0%) | 97 (61.4%) |

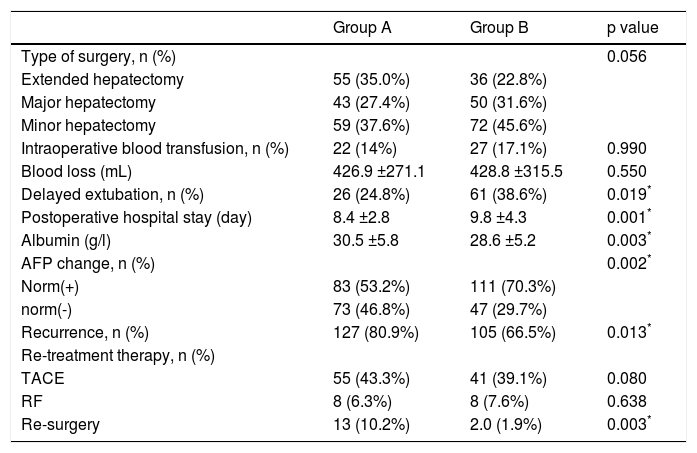

The types of surgery used in this study include minor hepatectomy (one segment), major hepatectomy (two or three segment) and extensive hepatectomy (more than three segments). A thorough intraoperative ultrasonography was performed to confirm the characteristics of each tumor. As shown in table 3, there were no significance differences in the type of surgery (p = 0.056), blood loss (p = 0.550), and intraoperative blood transfusion (p = 0.990) between group A and group B. After operation, group B had lower albumin levels and higher rates of patients with prolonged postoperative hospital stays than group A. The rate of recurrence until the final follow-up evaluation in group A was 80.9%, which was significantly higher than that of group B (66.5%, p = 0.013). Group A had a high percentage of patients receiving re-surgery due to HCC recurrence (10.2% vs. 1.9%, p = 0.003; table 3). The rate of patients who achieved normalized AFP (norm+) after surgery was higher in group B (53.2% vs. 70.3%), while the rate of patients with non-normalized AFP (norm-) (46.8% vs. 29.7%) after surgery was higher in group A (p = 0.002).

Surgery-related features and follow-up data.

| Group A | Group B | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of surgery, n (%) | 0.056 | ||

| Extended hepatectomy | 55 (35.0%) | 36 (22.8%) | |

| Major hepatectomy | 43 (27.4%) | 50 (31.6%) | |

| Minor hepatectomy | 59 (37.6%) | 72 (45.6%) | |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion, n (%) | 22 (14%) | 27 (17.1%) | 0.990 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 426.9 ±271.1 | 428.8 ±315.5 | 0.550 |

| Delayed extubation, n (%) | 26 (24.8%) | 61 (38.6%) | 0.019* |

| Postoperative hospital stay (day) | 8.4 ±2.8 | 9.8 ±4.3 | 0.001* |

| Albumin (g/l) | 30.5 ±5.8 | 28.6 ±5.2 | 0.003* |

| AFP change, n (%) | 0.002* | ||

| Norm(+) | 83 (53.2%) | 111 (70.3%) | |

| norm(-) | 73 (46.8%) | 47 (29.7%) | |

| Recurrence, n (%) | 127 (80.9%) | 105 (66.5%) | 0.013* |

| Re-treatment therapy, n (%) | |||

| TACE | 55 (43.3%) | 41 (39.1%) | 0.080 |

| RF | 8 (6.3%) | 8 (7.6%) | 0.638 |

| Re-surgery | 13 (10.2%) | 2.0 (1.9%) | 0.003* |

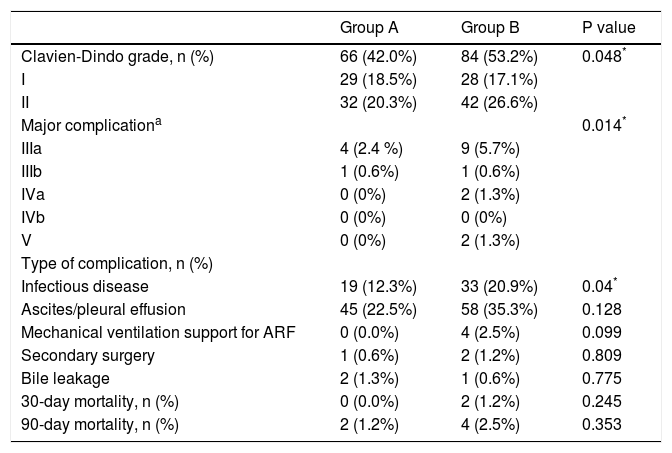

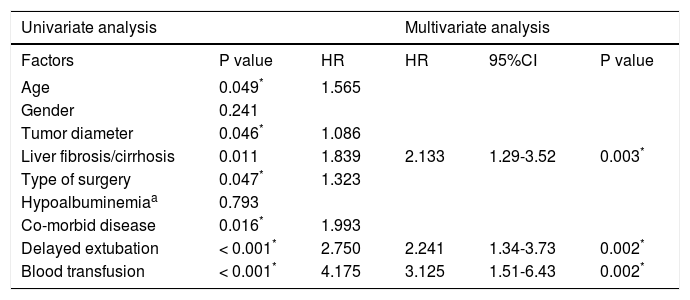

According to the Clavien-Dindo classification, the incidence of complications in the older age group B appeared to be higher (42.0% vs. 53.2%, p = 0.048). Group B had a higher proportion of major mortality (Clavien-Dindo Stage System III-V) than group A. During hospitalization, group B had 4 (2.5%) patients that required mechanical respiratory support for acute respiratory failure and 9 (5.7%) patients that required puncture drainage for pleural effusion. Among them, 2 (1.3%) patients died in hospital due to Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome. There were only 4 (2.4%) patients that required puncture drainage; no deaths were reported in group A. The percentage of patients who suffered infectious complications after liver resection was much higher in group B (12.3% vs. 20.9%, p = 0.04). No significant differences between both groups were observed regarding 30-day and 90-day postoperative mortalities. At 30 days, the mortality rate was 0.0% for group A and 1.2% for group B (p = 0.245). At 90 days, the mortality rate was 1.2% for group A and 2.5% for group B, respectively (p = 0.353) (Table 4). By univariate analyses, age, liver fibrosis/cirrhosis, tumor diameter, type of surgery, co-morbid disease, intraoperative blood transfusion and delayed extubation were significantly different between the two groups. Only intraoperative blood transfusion [hazard ratio (HR) 3.388, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.63-7.04, p = 0.001], liver fibrosis/cirrhosis (HR 2.133 95%CI 1.29-3.52 p = 0.003) and delayed extubation (HR = 2.341, 95%CI 1.39-3.92, p = 0.001) remained significant in multivariate analyses (Table 5).

Postoperative complications classification.

| Group A | Group B | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clavien-Dindo grade, n (%) | 66 (42.0%) | 84 (53.2%) | 0.048* |

| I | 29 (18.5%) | 28 (17.1%) | |

| II | 32 (20.3%) | 42 (26.6%) | |

| Major complicationa | 0.014* | ||

| IIIa | 4 (2.4 %) | 9 (5.7%) | |

| IIIb | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| IVa | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.3%) | |

| IVb | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| V | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.3%) | |

| Type of complication, n (%) | |||

| Infectious disease | 19 (12.3%) | 33 (20.9%) | 0.04* |

| Ascites/pleural effusion | 45 (22.5%) | 58 (35.3%) | 0.128 |

| Mechanical ventilation support for ARF | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (2.5%) | 0.099 |

| Secondary surgery | 1 (0.6%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.809 |

| Bile leakage | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.775 |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.245 |

| 90-day mortality, n (%) | 2 (1.2%) | 4 (2.5%) | 0.353 |

Factors associated with postoperative complications.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | P value | HR | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age | 0.049* | 1.565 | |||

| Gender | 0.241 | ||||

| Tumor diameter | 0.046* | 1.086 | |||

| Liver fibrosis/cirrhosis | 0.011 | 1.839 | 2.133 | 1.29-3.52 | 0.003* |

| Type of surgery | 0.047* | 1.323 | |||

| Hypoalbuminemiaa | 0.793 | ||||

| Co-morbid disease | 0.016* | 1.993 | |||

| Delayed extubation | < 0.001* | 2.750 | 2.241 | 1.34-3.73 | 0.002* |

| Blood transfusion | < 0.001* | 4.175 | 3.125 | 1.51-6.43 | 0.002* |

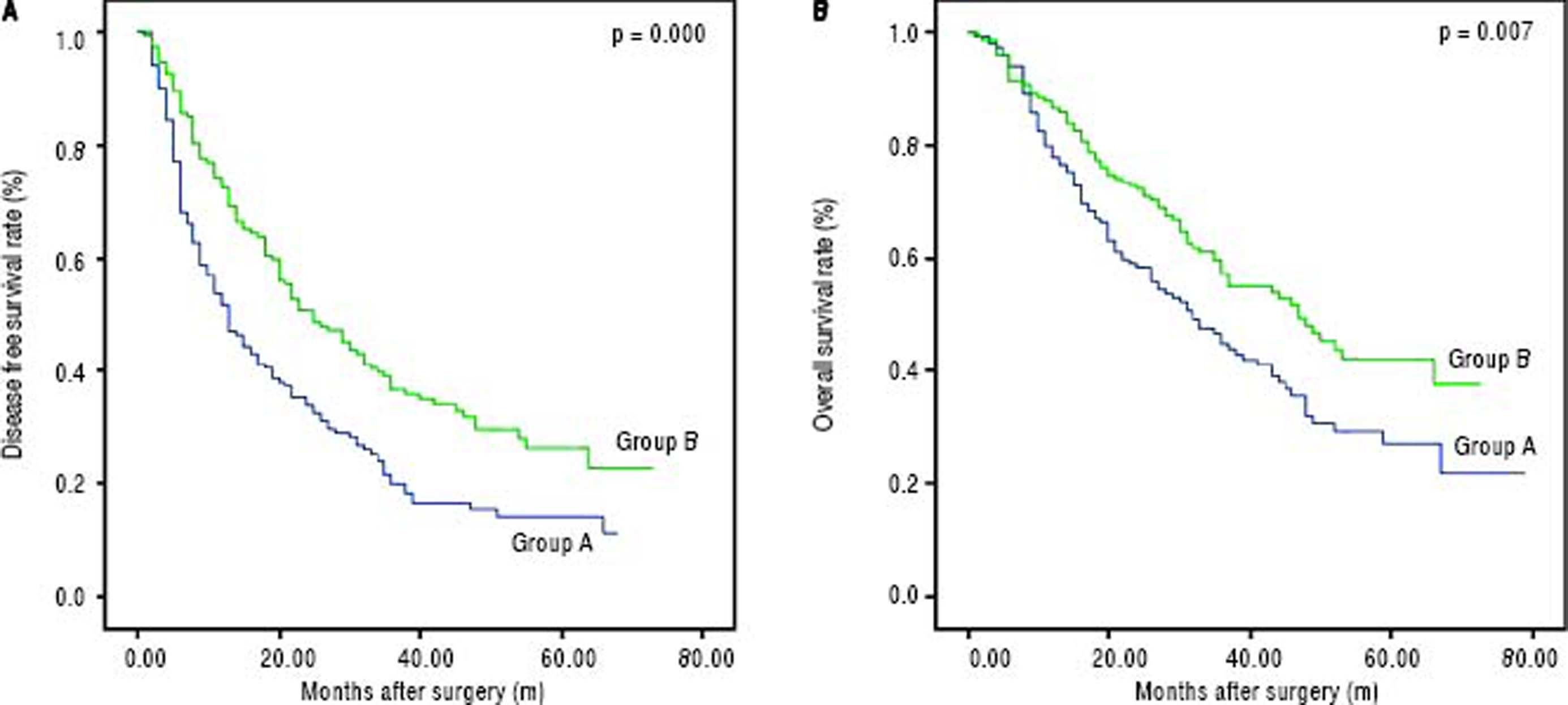

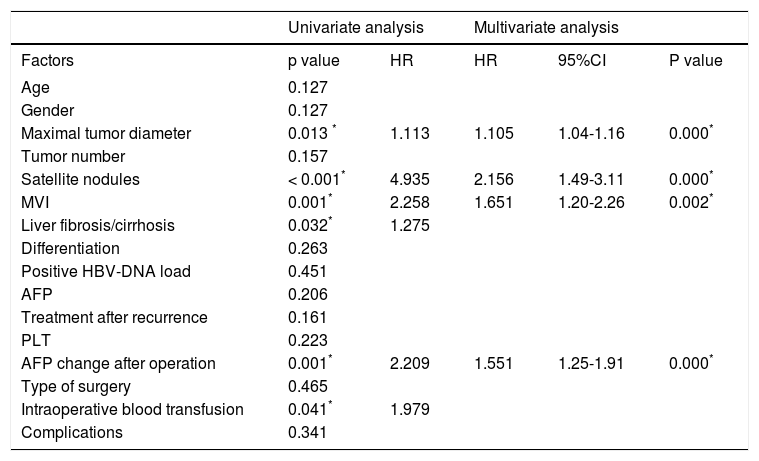

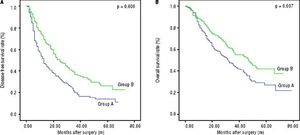

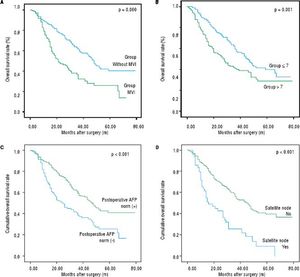

The disease-free survival rates after hepatectomy at 1, 3, and 5-years were 51.6%, 19.9%, and 14.3% in group A, respectively, and 72.4%, 36.7% and 26.5% in group B, respectively. The overall survival rates after hepatectomy at 1, 3, and 5-years were 78.1%, 45.1%, and 27.4% in group A, respectively, and 86.5%, 57.5% and 42.4% in group B, respectively. Significant differences were observed (Figures 2A and 2B) (p < 0.05). The median overall survival of group A and group B were 32.0 mo and 47.0 mo, respectively. Among the risk factors for overall survival, MVI, tumor size, postoperative AFP, tumor differentiation, presence of satellite nodules, liver fibrosis/cirrhosis and intraoperative blood transfusion were significant under univariate analyses (all p < 0.05). MVI (HR 1.651, 95% CI 1.20-2.26, P = 0.002), tumor size (HR 1.105, 95% CI 1.04-1.16, P = 0.000), postoperative AFP (HR 1.551, 95% CI 1.12-1.91, P = 0.009), presence of satellite (HR 2.065, 95% CI 1.3-3.1, P = 0.000) remained significant risk factors in multivariate analyses (Table 6). Patients with negative MVI, satellite node postoperative AFP normalization and large tumor sizes had better long-term survival than those without. (Figures 1A-1D) Interestingly, MVI, postoperative AFP level and tumor size as risk factors were not similar between both groups (Tables 2 and 3).

The curves of DFS and OS between group A. and group B. A. The DFS rates at 1, 3 and 5-years were 51.6%, 19.9% and 14.3% in group A, respectively, and 72.4%, 36.7% and 26.5% in group B. respectively. B. The OS rates at 1, 3 and 5-years between group A and group B were 80.0%, 45.1% and 27.4% in group A, respectively, and 87.8%, 57.5% and 42.4% in group B, respectively.

Prognostic factors associated with overall survival.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | p value | HR | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age | 0.127 | ||||

| Gender | 0.127 | ||||

| Maximal tumor diameter | 0.013 * | 1.113 | 1.105 | 1.04-1.16 | 0.000* |

| Tumor number | 0.157 | ||||

| Satellite nodules | < 0.001* | 4.935 | 2.156 | 1.49-3.11 | 0.000* |

| MVI | 0.001* | 2.258 | 1.651 | 1.20-2.26 | 0.002* |

| Liver fibrosis/cirrhosis | 0.032* | 1.275 | |||

| Differentiation | 0.263 | ||||

| Positive HBV-DNA load | 0.451 | ||||

| AFP | 0.206 | ||||

| Treatment after recurrence | 0.161 | ||||

| PLT | 0.223 | ||||

| AFP change after operation | 0.001* | 2.209 | 1.551 | 1.25-1.91 | 0.000* |

| Type of surgery | 0.465 | ||||

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 0.041* | 1.979 | |||

| Complications | 0.341 | ||||

The curves of OS for patients exceeding Milan criteria subdivided by MVI, tumor sizes > 7 cm, postoperative AFP and satellite node. A. The OS rates at 1, 3 and 5-years in patients with MVI were 72.7%, 32.2% and 25.7%, respectively; 40.3% patients without MVI. B. The OS rates at 1, 3 and 5-years were 89.0%, 59.4% and 40.0% in patients with tumor sizes ≤ 7 cm, respectively, and 73.9%, 41.3% and 29.1% in patients with tumor sizes >7 cm, respectively C. The OS rates at 1, 3 and 5-years were 88.6%, 59.3% and 40.8% in patients with AFP norm (+), respectively, and 71.8%, 38.5% and 25.5% in patients with AFP norm (-), respectively; d. The OS rates at 1, 3 and 5-years were 85.8%, 56.1% and 39.6% in patients without satellite node, respectively, and 63.3%, 25.7% and 9.2% in patients with satellite nodes, respectively.

Surgical resection is widely utilized for HCC patients capable of liver surgery. A resection can improve survival for an HCC patient regardless of tumor burden if the liver function was permissive.5 However, postoperative complications cannot be ignored especially in older patients. We defined 55-years-old as the cutoff value because many studies suggested that age was a risk factor of HCC mortality and that the risk score for patients older than 55 was increased.16–18 In this study, 47.6% patients suffered postoperative complications, and 5.4% patients experienced major complications. With advances in surgical techniques and improvements in postoperative management, hepatic resection mortality could decrease to < 1-3%.21’22 Our results showed that 90-day mortality was 1.7% in HCCs exceeding the Milan criteria; no significant differences were observed between young and older patients. Older patients had a higher rate of developing complications, especially major complications (53.3% vs. 42.0%, p < 0.05).

Transient liver failure, intra-abdominal bleeding, bile leak, sepsis and wound infection were commonly reported complications requiring liver resection. In this study, blood transfusion, delayed extubation and liver fibrosis/ cirrhosis were independent factors related to postoperative complications in the univariate and multivariate analyses. An association between transfusion and postoperative complications has been previously reported. The requirement for a blood transfusion is a well-established risk factor for postoperative complications in patients following abdominal surgery.23–25 Blood transfusions suppress host immunity via reductions in natural killer cell activity and cytotoxic T-cell function.26 In HCC patients undergoing hepatectomy, immunosuppressive effects may likely contribute to postoperative complications. Liver cirrhosis was another predictor of postoperative complications in the present study. Underlying liver fibroses and cirrhosis negatively impacted liver regeneration and liver failure.27 This point was proved in our study. Cirrhotic patients should avoid a major hepatectomy and preserve as much liver tissue as possible. Delayed extubation was also an unfavorable factor associated with complications, especially in older patients.28,29 Like a history of pulmonary disease, age and co-morbidity were important factors associated with prolonged intubation times after surgery. Liver disease was commonly attributed to altered pharmacodynamics, leading to longer extubation times.30 Delayed extubations may also reflect a poor liver function status. The preoperative albumin level was lower in older patients than young patients, suggesting a malnutrition status.31 The decision to delay extubation may also be an indicator of poor pulmonary function reserve.25 These may contribute toward prolonged intubation after surgery and correlate with developing complications such as pneumonia and abdominal ascites later in the postoperative period. Compared with factors such as age and co-morbidity, delayed extubation as a reflection of physiologic changes was a more accurate predictor for postoperative complications. In our study, older patients had a higher rate of delayed extubation. This may be correlated with a higher percentage of postoperative infectious complications. The length of hospital stay was considerably longer in older patients. Older patients suffered more infectious complications. Improved liver functions and preoperative respiratory exercises advantageously reduce postoperative complications, especially for older patients.

In agreement with previous studies, age was not associated with long-term survival in the present study.32,33 However, compared with older patients, young HCC patients seem to have heavier tumor burdens as indicated by larger tumor sizes, higher rates of satellite nodes and MVIs. Elevated preoperative AFP levels in young HCC patients also suggested the tumors were highly aggres-sive.34 The prognoses of HCC patients largely depend on the tumor characteristics at the times the patients could tolerate surgery.35 In our study, older patients achieved a better 5-year survival. Tumor size, presence of satellite nodes, MVI and postoperative AFP were independent risk factors associated with long-term survival. Large tumor sizes increased the risk of metastases.36 Satellite nodes and MVI have been identified as accepted risk factors for poor prognoses in some solid tumors.37–39 Patients with MVI and satellite nodes suffered more HCC recurrences. Furthermore, there may be intrahepatic metastases beyond the resection field, and the removal of the gross tumor alone will not be enough. HCC treatment guidelines do not feature MVI and satellite nodes as factors in recommending treatment options. The need for effective adjuvant therapy and close follow-up should be taken into account in patients with these risk factors. The postoperative AFP level was reportedly associated with recurrence after curative hepatectomy. A high postoperative AFP level after operation may suggest potentially residual viable tumor cells. An elevated AFP is commonly related to the aggressive ability of a tumor and has been identified as an adverse factor in the prognoses of HCCs after hepatectomies.34 Young patients commonly had more advanced tumors with higher rates of MVI, larger tumor sizes and high postoperative AFP levels. Interestingly, the three risk factors strongly influenced the prognoses of these patients (Figures 1A-1C, p < 0.05). Young and old patients presented different HBV subgenotype integrations. An HBV B2 integration was predominantly present in young patients, contributing to the development of early-onset HCC. A few studies have reported worse prognoses in early-onset HCC patients.15 Additionally, young patients had advanced tumors at the times of diagnoses due to poor surveillance. These factors may have ultimately contributed to poor prognoses.

ConclusionIn contrast with young HCC patients, older patients had a higher rate of complications, especially major complications. In order to decrease complications, blood transfusions should be avoided. Furthermore, improved liver functions and increased respiratory exercises should be followed, especially for older patients. Young patients seemed to suffer worse prognoses partly due to more advanced tumors. Patients with risk factors, such as MVIs, satellite nodes, large tumor sizes and high postoperative AFP levels, should be closely monitored and provided aggressive therapies such as TACE.

Abbreviations- •

AFP: alpha fetoprotein.

- •

CI: confidence interval.

- •

DFS: disease free survival.

- •

HBV: hepatitis B viral.

- •

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

- •

HR: hazard ratio.

- •

MVI: microvascular invasion.

- •

OS: overall survival.

- •

RF: radiofrequency ablation.

- •

TACE: transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.

The authors have received no financial support in the conduct of this study. The authors have no conflicts of interest.