Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks among the most lethal cancer entities, with approximately 830,000 deaths caused worldwide in 2020 [1]. Most HCCs are diagnosed at an advanced stage, thus requiring systemic treatment [2]. The combination of the immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) atezolizumab and the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor bevacizumab (atezo/bev) has revolutionized treatment algorithms for advanced HCC and has substantially improved patient outcomes as compared to the previous first-line therapy sorafenib [3,4]. However, despite its remarkable efficacy in some patients, clinical endpoints remain compromised in a large fraction of patients. Importantly, ICI-induced hyperactivation of the immune system can lead to the development of immune-related adverse events (irAE), which can result in iatrogenic immune-mediated diseases in multiple organs, often necessitating treatment discontinuation. Thus, the identification of biomarkers that could help to predict treatment response is crucial to select patients who will most likely benefit from this oncological therapy and to avoid potentially serious side effects in patients who most likely will not benefit from immunotherapy.

Considering that tissue biopsy is not mandatory for HCC diagnosis, the development of tissue-related biomarkers in HCC is limited [5]. Thus, identifying circulating biomarkers for predicting treatment efficacy and patient prognosis is of major interest in this entity [6]. In this context, cytokines, which represent immunological messenger molecules acting in a paracrine as well as systemic manner, shape immunity in homeostasis and disease and can be critically involved in the regulation of anti-cancer immune responses [7–9]. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pleiotropic cytokine secreted by a variety of cell types including different immune cell subsets, stromal cells such as fibroblasts and endothelial cells as well as cancer cells [10]. Upregulation of systemic IL-6 has been reported for diverse cancer entities and has been linked to cancer cell biology, including survival, proliferation, invasiveness and formation of a metastatic niche [8,11,12]. Furthermore, hyperactivation of the IL-6 signaling cascade has been described to dampen T cell-based anti-tumor immunity and to represent an important resistance mechanism to cancer immunotherapy in a plethora of cancer entities [8,13–15]. In the context of liver disease, IL-6 levels increase in a hierarchical manner from healthy tissue towards hepatitis, cirrhosis, and HCC, thereby establishing a pro-tumorigenic state [16–19]. Regarding HCC, high serum IL-6 levels were attributed to reduced clinical benefit of immunotherapy in several East Asian HCC cohorts [20–22]. The applicability of these results to Western patients remains uncertain due to demographic and genetic differences, as well as variations in the underlying etiology of HCC. In the cohorts mentioned, Hepatitis B Virus infection was the primary driver of malignancy, affecting over 70 % of patients. In contrast, in Western countries, a larger proportion of HCC cases arise from alcohol-related or metabolic liver cirrhosis. These differences result in substantial variations in the immunological and molecular phenotypes between viral, alcohol-related, and metabolic liver damage, leading to distinct tumor microenvironments in HCC. Consequently, it is unclear whether the finding that serum IL-6 serves as a predictive biomarker for atezo/bev-treated HCC patients can be applied to Western HCC cohorts. [23].

In this multicenter study, we aimed to comprehensively address the role of systemic IL-6 levels in advanced HCC patients receiving atezo/bev in a large Western real-world cohort. Our study suggests that elevated serum IL-6 may serve as a negative prognostic biomarker in atezo/bev-treated HCC patients and highlights its potential biological relevance in HCC patients receiving immunotherapy.

2Materials and Methods2.1Patient populationPatient data was recruited from two centers in Germany (University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, University Hospital LMU Munich) and one center in Austria (Medical University of Vienna). All patients included in this study had confirmed HCC diagnosis based on histopathological findings or diagnostic imaging criteria according to the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) [24]. All patients who received immunotherapy with atezo/bev were eligible for inclusion. No patients were excluded. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hamburg Medical Association (#PV3578), the Ethic Committee of the LMU Munich (18–604, 20–439), and the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (2033/2017). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist was used during manuscript preparation [25]. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Istanbul. This study was not registered in a clinical trial registry.

2.2Treatments and assessmentsAll patients received the following treatment regimen: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (atezo/bev), with atezolizumab being administered intravenously at a dose of 1200 mg and bevacizumab at 15 mg per kg of body weight every three weeks. Monitoring of patients comprised clinical, laboratory, and imaging evaluations, according to the established standard of care per EASL HCC guidelines [24]. Tumor response was assessed every 8 to 12 weeks through computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging and evaluated according to mRECIST criteria.

2.3EndpointsThe primary endpoint of this study was to investigate overall survival (OS) in the study cohorts depending on the serum cytokine levels. Secondary endpoints included progression-free survival (PFS) and response rates. OS was defined as the time from treatment initiation until death from any cause. PFS referred to the period from treatment initiation to disease progression on radiological assessment or death from any cause. Patients without recorded OS or PFS events or patients who were lost to follow-up were censored at the date of their most recent contact. Radiological response was characterized as complete or partial response (CR/PR), stable or progressive disease (SD/PD) by the local investigator. Overall response rate (ORR) was the proportion of patients experiencing CR and PR, while disease control rate (DCR) was defined as CR plus PR plus SD.

2.4Specimen collection and serum preparationBlood specimens were drawn into serum-separating tubes before the initiation of therapy and processed within 6 h. The blood was centrifuged for 10 min at 1800 g, and the serum was collected and stored at −20 °C and −80 °C until use.

2.5Serum cytokine detectionFor serum cytokine quantification LEGENDplex™ HU Th1 Panel (5-plex) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions (Biolegend, USA). Flow cytometry was performed on an LSRII Flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA). Data was analyzed using the LEGENDplex™ data analysis software (Biolegend, USA).

2.6StatisticsOptimal cytokine cut-off values of the discovery cohort (University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf) were calculated using the CutoffFinder web application [26]. The optimal cut-off was defined as the point with the most significant (log-rank test) split. Patients were divided into high and low groups according to the determined cut-off value. Patients of the validation cohorts (University Hospital LMU Munich, Medical University of Vienna) were subdivided into these groups using the same cut-off value.

We used Fisher’s exact test and Student’s t-test to compare differences between categorical and continuous variables, respectively. For Cox regression modeling of non-binary coded parameters, a dichotomous fashion was used. OS and PFS were analyzed using log-rank test (Mantel–Haenszel Version) and plotted with Kaplan Meier curves. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was conducted and variables that were judged as clinically relevant according to available literature were included in the multivariable model.

For all statistical analyses, p-values below 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were conducted on GraphPad Prism (Version 10.5.0).

3Results3.1Patient characteristicsFrom January 2020 to October 2023 participants with advanced HCC treated with atezo/bev were prospectively enrolled in this biomarker study at three tertiary referral centers in Europe. In total, 143 patients were included in this European multi-center study. Patients were divided into a discovery cohort (63 patients from the Hamburg center) and a validation cohort (80 patients from two centers; 38 from the Vienna center, 42 from the Munich center). The baseline characteristics of these cohorts are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 67.2 years. This patient cohort consisted of 121 (84.6 %) men and 22 (15.4 %) women. The mean age of the patients was 68.4 years. 110 (76.9 %) of patients had confirmed cirrhosis at the time of HCC diagnosis. Etiology of the underlying liver disease was distributed as follows: Chronic viral hepatitis (n = 10 chronic hepatitis B, n = 31 chronic hepatitis C), metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (n = 21), alcohol-associated liver disease (n = 50), other causes (n = 7; adenoma: 1 patient, autoimmune hepatitis: 1 patient, primary biliary cholangitis: 1 patient, hemochromatosis: 2 patients, Wilson's disease: 1 patient, chronic aflatoxin exposure: 1 patient) and 26 cases of unknown or cryptogenic etiology. For patients with multiple risk factors, each risk factor was included. In 33 (23.1 %) cases, tumor burden was classified as Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage B, while 102 (71.3 %) cases were classified as BCLC stage C, and 8 cases were classified as BCLC stage D. Overall, our cohort reflects a typical cohort for unresectable HCC in Western tertiary centers.

Baseline characteristics.

| Baseline characteristics | Total cohort(n=143) | Discovery(n=63) | Validation(n=80) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender ( %) | |||

| Male | 121 (84.6 %) | 57 (90.5 %) | 64 (80.0 %) |

| Female | 22 (15.4 %) | 6 (9.5 %) | 16 (20.0 %) |

| Age | |||

| Mean ± SD | 67.2 ± 9.5 | 68.4 ± 9.1 | 66.3 ± 9.8 |

| Liver cirrhosis ( %) | |||

| Yes | 110 (76.9 %) | 54 (85.7 %) | 56 (70.0 %) |

| No | 33 (23.1 %) | 9 (14.3 %) | 24 (30.0 %) |

| CPS ( %) | |||

| Not available | 1 (0.9 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 1 (1.8 %) |

| A | 56 (50.9 %) | 26 (48.1 %) | 30 (53.6 %) |

| B | 46 (41.8 %) | 25 (46.3 %) | 21 (37.5 %) |

| C | 7 (6.3 %) | 3 (5.6 %) | 4 (7.1 %) |

| ALBI grade | |||

| Not available | 1 (0.7 %) | 1 (1.6 %) | 0 (0.0 %) |

| I | 46 (32.2 %) | 11 (17.5 %) | 35 (43.8 %) |

| II | 80 (55.9 %) | 38 (60.3 %) | 42 (52.5 %) |

| III | 16 (11.2 %) | 13 (20.6 %) | 3 (3.7 %) |

| Etiology of liver disease# | |||

| Alcohol | 50 (35.0 %) | 26 (41.3 %) | 24 (30.0 %) |

| MASLD | 21 (14.7 %) | 12 (19.0 %) | 9 (11.3 %) |

| Hepatitis B | 10 (7.0 %) | 3 (4.8 %) | 7 (8.8 %) |

| Hepatitis C | 31 (21.7 %) | 12 (19.0 %) | 19 (23.8 %) |

| Other or unknown | 33 (21.7 %) | 10 (15.9 %) | 21 (25.0 %) |

| ECOG ( %) | |||

| 0 | 79 (55.2 %) | 21 (33.3 %) | 58 (72.5 %) |

| 1 | 56 (39.2 %) | 37 (58.7 %) | 19 (23.7 %) |

| 2 | 8 (5.6 %) | 5 (7.9 %) | 3 (3.8 %) |

| BCLC classification ( %) | |||

| B | 33 (23.1 %) | 15 (23.8 %) | 18 (22.5 %) |

| C | 102 (71.3 %) | 45 (71.4 %) | 57 (71.3 %) |

| D | 8 (5.6 %) | 3 (4.8 %) | 5 (6.3 %) |

| Macrovascular invasion ( %) | |||

| No | 76 (53.1 %) | 27 (42.9 %) | 49 (61.3 %) |

| Yes | 67 (46.9 %) | 36 (57.1 %) | 31 (38.8 %) |

| Extrahepatic spread ( %) | |||

| No | 81 (56.6 %) | 41 (65.1 %) | 40 (50.0 %) |

| Yes | 62 (43.4 %) | 22 (34.9 %) | 40 (50.0 %) |

| AFP ( %) | |||

| < 400 ng/ml | 91 (63,6 %) | 43 (68.3 %) | 48 (60.0 %) |

| ≥ 400 ng/ml | 48 (33.6 %) | 19 (30.1 %) | 29 (36.3 %) |

| Not available | 4 (2.8 %) | 1 (1.6 %) | 3 (3.8 %) |

| Serum IL-6 levels | |||

| Mean ± SD | 49.1 ± 107.4 | 52.8 ± 125.1 | 46.2 ± 91.9 |

| Median (IQR) | 21.1 (9.0 – 59.1) | 26.5 (7.9 – 52.6) | 18.1 (9.1 - 59.7) |

| ≥ 18.22 pg/ml | 77 (53.8 %) | 37 (58.7 %) | 40 (50.0 %) |

| < 18.22 pg/ml | 66 (46.2 %) | 26 (41.3 %) | 40 (50.0 %) |

Abbreviations: AFP, Alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; CPS, Child-Pugh class; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IL-6, interleukin-6; IQR, interquartile range; MASLD, Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease; SD, standard deviation.

We first performed a retrospective multiplex analysis of serum cytokines using a cytometric bead array (CBA) in patients who participated in the study at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. The patients were divided into groups with high or low cytokine levels based on the respective median value used as cut-off. Instead of using established cut-off finder algorithms for optimal separation of groups, we decided to use the median as an a priori cut-off to employ a fully unbiased screening of cytokine levels which might predict the survival of HCC patients undergoing atezo/bev treatment. From the 5 cytokines measured (Interferon-γ (IFN-γ), Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-2, IL-6 and IL-10) we identified that high levels of IL-6 (HR 2.4, 95 % CI 1.1–5.1, p = 0.025) and IL-10 (HR 2.3, 95 % CI 1.1–5.0, p = 0.032) were associated with reduced OS in the discovery data set (Fig. 1a-b) while no association with survival was found for serum cytokine levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2 (Fig. 1c-e). There were no significant differences in cytokine values between the discovery and validation cohorts.

Baseline cytokine measurement and biomarker screening for overall survival. IL-10 (a), IL-6 (b), IL-2 (c), IFN-γ (d), and TNF-α (e) were measured at baseline in the discovery and validation cohort. Overall survival (OS) is displayed as Kaplan–Meier curves according to median cytokine levels (above vs. below median). The p-value was calculated using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

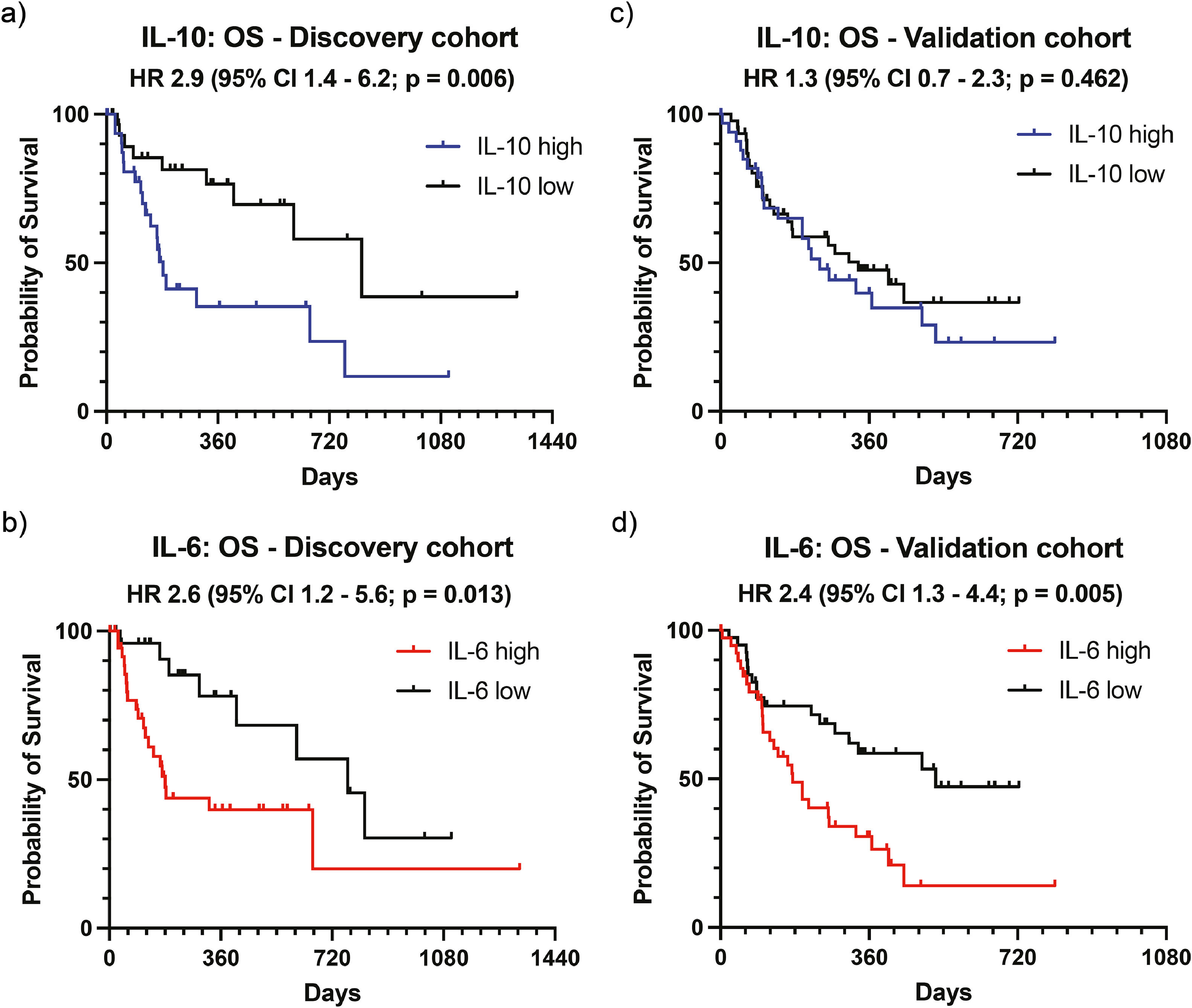

We next aimed to verify our findings observed in the discovery cohort from the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf in additional independent cohorts for validation of our results. To this end, we determined an optimal cut-off value as the point with the most significant (log-rank test) split as described previously [26]. Accordingly, the calculated cut-off value was 18.22 pg/ml for IL-6 and 1.198 pg/ml for IL-10. Based on these values, the discovery cohort was now categorized into an IL-6 high (n = 37) and an IL-6 low group (n = 26) and into an IL-10 high (n = 33) and an IL-10 low (n = 31) group. As expected, when using optimized cut-off values, the differences in OS were more pronounced for both IL-10 (HR 2.9, 95 % CI 1.4–6.2, p = 0.006, Fig. 2a) and IL-6 (HR 2.6, 95 % CI 1.2–5.6, p = 0.013, Fig. 2b) in the discovery cohort.

Validation of potential biomarkers for overall survival. The optimal cut-off values for IL-10 (1.198 pg/ml) and IL-6 (18.22 pg/ml) were calculated and patients categorized into high and low groups. Overall survival (OS) is displayed as Kaplan–Meier curves for IL-10 (a) and IL-6 (b) in the discovery and for IL-10 (c) and IL-6 (d) the validation cohort. The p-value was calculated using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

These determined cut-off values for IL-6 and IL-10 were now used to categorize the validation cohort, which consisted of 80 patients from two centers (38 from the Vienna center, 42 from the Munich center) treated with atezo/bev for HCC. Interestingly, in contrast to our discovery cohort, we observed no difference in OS for IL-10 levels in the validation cohort (HR 1.3, 95 % CI 0.7–2.3, p = 0.462, Fig. 2c). High levels of IL-6 (≥ 18.22 pg/ml, n = 40) were again associated with reduced OS compared to low IL-6 levels (< 18.22 pg/ml, n = 40), confirming the results from our discovery cohort (HR 2.4, 95 % CI 1.3–4.4, p = 0.005, Fig. 2d). Of note, the cut-off value for IL-6 identified in our cohort (18.22 pg/ml) is very close to the previously reported cut-off values of serum IL-6, which correlate with survival in published Asian cohorts. In those studies, the cut-off values identified were 18.49 pg/mL and 19.82 pg/ml 21, 22.

3.4Serum IL-6 levels are associated with progression-free survival in atezo/bev-treated HCC patientsWe next analyzed the PFS in the discovery and validation cohorts using the 18.22 pg/ml cut-off value for IL-6. No statistically significant differences were found for PFS in a separate analysis of discovery (HR 1.8, 95 % CI 0.9–3.4, p = 0.075, Fig. 3a) and validation cohort (HR 1.5, 95 % CI 0.9–2.6, p = 0.125, Fig. 3b), but pooled analysis of both cohorts demonstrated significantly improved PFS in patients with low serum IL-6 levels (HR 1.5, 95 % CI 1.0–2.3, p = 0.047, Fig. 3c). For further analysis, the entire cohort (discovery and validation cohorts joined) was divided into an IL-6 high and an IL-6 low group. The patient characteristics of these subgroups are presented in Table 2. While demographic parameters (gender, age), BCLC stage, AFP levels, and cirrhosis were equally distributed in both groups, HCC etiology was significantly different, with viral HCC being more present in IL-6 high patients (Table 2). Elevated IL-6 levels were associated with impaired liver function, as indicated by higher ALBI grades (p = 0.019). The ORR was 24.1 % in the IL-6 high group versus 32.1 % in the IL-6 low group, while the DCR was 58.5 % in the IL-6 high group versus 67.9 % in the IL-6 low group.

Analysis of progression-free survival according to IL-6 Levels. Patients were categorized into two groups, IL-6 high and IL-6 low, using a cut-off value of 18.22 pg/ml for baseline serum cytokine levels. Progression-free survival (PFS) is displayed as Kaplan–Meier curves for the discovery cohort (a), the validation cohort (b), and the total cohort (c). The p-value was calculated using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Subgroup analysis of HCC patients with low or high IL-6 levels.

| Baseline characteristics | Low(n=66) | High(n=77) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender ( %) | |||

| Male | 52 (78.8 %) | 69 (89.6 %) | 0.103 |

| Female | 14 (21.2 %) | 8 (10.4 %) | |

| Age | |||

| Mean ± SD | 67.6 ± 10.4 | 66.7 ± 8.7 | 0.479 |

| Liver cirrhosis ( %) | |||

| Yes | 51 (77.3 %) | 59 (76.6 %) | 0.999 |

| No | 15 (22.7 %) | 18 (23.4 %) | |

| ALBI grade | |||

| Not available | 1 (2.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.019⁎ |

| I | 28 (60.7 %) | 18 (49.0 %) | |

| II | 31 (35.3 %) | 49 (54.9 %) | |

| III | 6 (19.6 %) | 10 (11.8 %) | |

| Viral etiology of disease ( %) | |||

| Viral | 12 (18.2 %) | 26 (33.8 %) | 0.039 |

| Non-viral | 54 (81.8 %) | 51 (66.2 %) | |

| BCLC ( %) | |||

| B | 17 (25.8 %) | 16 (20.8 %) | 0.552⁎⁎ |

| C | 48 (72.7 %) | 54 (70.1 %) | |

| D | 1 (1.5 %) | 7 (9.1 %) | |

| ORR | 17 (32.1 %) | 14 (24.1 %) | 0.406 |

| DCR | 36 (67.9 %) | 34 (58.5 %) | 0.332 |

| AFP ( %) | |||

| < 400 ng/ml | 21 (31.8 %) | 27 (35.1 %) | 0.723 |

| ≥ 400 ng/ml | 43 (65.2 %) | 48 (62.3 %) | |

| Not available | 2 (3.0 %) | 2 (2.6 %) | |

| Serum IL-6 levels | |||

| Mean ± SD | 8.9 ± 4.7 | 83.5 ± 137.6 | <0.0001 |

| Median (IQR) | 8.7 (4.8 – 13.1) | 52.6 (29.1 – 88.3) | |

Abbreviations: AFP, Alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; DCR, Disease control rate, IL-6, interleukin-6; IQR, interquartile range; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ORR, objective response rate; SD, standard deviation.

The joined analysis of both cohorts again showed a clear association between low levels of IL-6 (< 18.22 pg/ml) and improved OS (HR 2.3, 95 % CI 1.5–3.7, p = 0.0004, Supp. Figure 1a). Harrell’s C-index for continuous IL-6 levels was 0.6470 (95 % CI 0.5858 – 0.7081). The HR of IL-6 per unit of increase was 1.003 (95 % CI 1.001 – 1.004; p = 0.0017).

Since viral etiology was significantly less common in the IL-6 low group, a subgroup analysis was conducted on patients without viral involvement to determine whether IL-6 levels are prognostic for OS in patients with non-viral HCC (Supp. Figure 1b). In this subgroup, patients with IL-6 levels above 18.22 pg/ml also demonstrated poorer OS (HR 2.0, 95 % CI 1.1–3.6, p = 0.015).

Furthermore, a subgroup analysis was performed, excluding all patients with BCLC stage D (Supp. Figure 1c), since current European guidelines do not recommend systemic anti-tumor therapy in these patients. Also in this subgroup analysis, patients with high IL-6 serum levels continue to exhibit reduced OS (HR 2.2, 95 % CI 1.3–3.6, p = 0.0017).

3.6Serum IL-6 is an independent prognostic marker in a multivariate analysis of overall survivalThe effects of IL-6 serum levels, tumor characteristics, and patient characteristics on OS were examined using univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 3, Supp. Table 1). This was followed by a multivariate analysis of all variables that were judged as clinically relevant according to available literature. In our cohort, BCLC stage, AFP, and ECOG performance status did not predict OS. ALBI grade and IL-6 levels reached statistical significance as predictors of OS in the univariate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, both IL-6 status (HR 1.9, 95 % CI 1.1–3.3, p = 0.013) and ALBI grade (HR 3.1, 95 % CI 1.8–6.0, p < 0.0001) persisted to represent independent predictors of OS, while AFP emerged as a predictor of survival after adjustment in the multivariate analysis (HR 1.8, 95 % CI 1.1–3.0, p = 0.023). Additionally univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed for PFS as a secondary endpoint (Supp. Table 2).

Cox proportional hazards regression of discovery and validation cohort for overall survival.

The following variables were included in the multivariate model: ALBI, viral etiology, BCLC, ECOG, AFP, and IL-6. Abbreviations: AFP, Alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

In this multicenter study, we comprehensively addressed the role of systemic IL-6 levels in advanced HCC patients receiving atezo/bev in a large Western real-world biomarker study. Using a discovery and a validation cohort comprising 143 patients from three European reference centers and systemic measurements of five different cytokines, we could demonstrate that high serum IL-6 levels were significantly associated with poor OS in this Western patient cohort. Additionally, we could determine an optimized IL-6 cut-off value of 18.22 pg/ml, which closely aligns with the values identified in two large East Asian studies, which reported cut-off points of 18.49 pg/ml and 19.82 pg/ml respectively [21,22]. Interestingly, a large multicenter study from Korea recently identified IL-2, IL-12, C-reactive protein (CRP), and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, but not IL-6, as prognostic biomarkers in HCC patients treated with atezolizumab/bevacizumab. This highlights the need for further studies to clarify the validity of IL-6 as a prognostic biomarker in this setting [27]. Furthermore, the fact that high serum IL-10 was associated with clinical outcomes in the discovery, but not the validation cohort, highlights the importance of using validation cohorts in similar studies to avoid false positive results. Early increases in serum levels of IL-10 and TNF-α following treatment have recently been identified as potential prognostic markers for survival in a small prospective Korean study [28]. Additionally, a recent Japanese multicenter analysis found that IL-6 levels at the start of the second course of atezolizumab/bevacizumab therapy may serve as a prognostic biomarker for overall survival [29]. Further studies are needed to evaluate the dynamic changes in cytokine levels during treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitor regimens.

Altogether, the identification of serum IL-6 as a strong biomarker of OS in Western HCC patients through this unbiased approach underscores the biological relevance of IL-6 in this entity, thus providing a rationale to use serum IL-6 levels as a prognostic biomarker for Western HCC patients undergoing systemic therapy with atezo/bev.

The objective of this study was to evaluate serum cytokine levels as potential prognostic biomarkers for patient outcomes with advanced unresectable HCC undergoing ICI therapy in a Western cohort. While IL-6 has already been established as a prognostic and predictive biomarker for patients in East Asian patient cohorts, hepatitis B infection was detected in over 70 % of patients in these cohorts [20–22]. Previous studies have demonstrated that chronic hepatitis B infection is associated with elevated serum IL-6 [30]. Thus, the transferability of these results to a Western cohort in which hepatitis B plays a less pronounced role has not yet been established. While East Asian studies demonstrated a role for serum IL-6 in predicting treatment response, our cohorts showed only a moderately improved PFS in a combined analysis of all patients, whereas the differences between the IL-6 high and IL-6 low groups in ORR of 24.1 % versus 32.1 %, and DCR of 58.5 % versus 67.9 % were not statistically significant. Of note, the baseline characteristics of this real-world Western cohort indicated significantly worse liver function and OS of the total cohort compared to a previously published Korean cohort [22]. Poor liver function prior to treatment initiation may mask effects on treatment response in our cohort compared to healthier pre-selected patients.

Serum IL-6 levels are influenced by a range of factors, including tumor burden, tumor biology, cirrhosis stage, unfavorable patient characteristics such as sarcopenia, and the underlying etiology of liver disease [16–19,31]. An analysis of the baseline characteristics of the IL-6 low and IL-6 high groups revealed more cases of chronic viral hepatitis and higher ALBI grade in the IL-6 high cohort. To exclude the possibility that these potential confounder variables could explain the differences in OS, a univariate Cox regression analysis of known factors influencing the OS of HCC patients was first performed. In the univariate analysis, ALBI and IL-6 status were found to be significant predictors of OS. In a multivariate analysis of these two parameters, both parameters remained significant. We conclude that IL-6 level is a prognostic parameter for OS, independent of other known risk stratifications.

Elevated IL-6 or CRP levels have been identified as unfavorable prognostic markers in various types of tumors [32–35]. Given that IL-6 induces the production of acute phase proteins such as CRP in the liver, serum IL-6 levels are closely correlated with CRP levels [16]. Notably, a Chinese study confirmed this correlation in HCC patients treated with atezo/bev [21]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the CRAFITY score, derived from AFP and CRP levels, can serve as a predictive marker for treatment response in HCC [36]. The multitude of potential factors influencing serum IL-6 levels complicates the differentiation between predictive and prognostic properties of IL-6. However, compelling studies in rodent models have demonstrated that excessive IL-6 shifts the anti-tumor immune response from a favorable Th1-driven anti-tumor response to an unfavorable Th17-driven response, leading to irAE. Conversely, IL-6 blockade restored the immune response to an IL-12-mediated Th1 anti-tumor response [15]. These promising preclinical findings prompted the initiation of a Phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT04524871) to evaluate the combination therapy of atezo/bev in patients with HCC, augmented by the addition of the anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab.

The study design has inherent limitations and strengths that should be acknowledged while interpreting the results. The use of patients from a real-world setting strengthens the applicability of the results to clinical practice. The study confirms previous East Asian studies for the first time in a large cohort in which hepatitis B infection only plays a minor role. The multicenter design using a discovery and validation cohort underlines the robustness of IL-6 as a prognostic marker. Due to the pleiotropic function of IL-6 and a myriad of factors influencing serum IL-6 levels, it remains challenging to reliably determine the source of IL-6 in blood. Thus, differentiating the treatment-related properties of serum IL-6 levels in HCC patients remains challenging due to the influence of various factors related to both the tumor and underlying liver disease. However, our cohort reflects real-world clinical practice, highlighting the clinical significance of serum IL-6 irrespective of its potential source. Finally, informed consent for blood testing was obtained from each patient prior to serum analysis, potentially introducing inclusion bias.

5ConclusionsThis study validated serum IL-6 levels as a potent prognostic biomarker for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing systemic treatment with atezolizumab and bevacizumab. IL-6 serum levels were able to predict OS and PFS in a multi-center Western HCC cohort with a multitude of underlying etiologies, thus providing a reliable parameter in clinical practice to predict patient prognosis and to facilitate clinical decision making in Western HCC cohorts.

FundingL.K. is supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) - Project-ID 546185154. This research was funded by the Else Kröner Memorialstipendium (Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung; to J.K.), the Werner Otto Stiftung (Grant to J.K.), the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (J.K.). JvF is supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, grant 01EO2106), German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe), and Wilhelm Sander Foundation. I.P. is supported by the Bavarian Cancer Research Center, the Stiftungen zu Gunsten der Medizinischen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilian-Universität München (Cluster 1) and the Novartis Foundation.

Author contributionsStudy conceptualization: L.K., J.K., J.vF., K.S; Data collection and curation: All authors; Formal analysis: L.K., J.K., I.P; Writing – original draft: L.K., J.K., I.P., L.B., M.P., B.S., K.S., J.vF; Writing – review & editing: All authors.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work, the authors used perplexity.ai to proofread for spelling errors and improve readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the publication's content.

L.B. received speaking fees from Chiesi, and Gilead. M.P. served as a speaker and/or consultant and/or advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Ipsen, Lilly, MSD, and Roche, and received travel support from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ipsen, and Roche. B.S. received travel support from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Gilead, Ipsen and Roche, speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca and Eisai, grant support from Astra Zeneca and Eisai as well as honoraria for consulting from AstraZeneca. N.B.K. advises for Roche and Ipsen, has received reimbursement of meeting attendance fees and travel expenses from EISAI, lecture honoraria from Falk and Astra Zeneca. J.R. received grants and personal fees from Sirtex and Bayer. JvF received advisory board fees and lecturing fees from Roche and AstraZeneca. I.P. reports reimbursement of travel expenses from Roche and received third-party funding for scientific research from Novartis. K.S. reports honoraria for speaker, consultancy and advisory role from Roche, AstraZeneca, and MSD. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Sub-analysis of the total cohort. Overall survival (OS) is displayed as Kaplan-Meier curves for the total cohort (a), the total cohort excluding all patients with a viral etiology of HCC (b), and the total cohort excluding all patients with BCLC stage D (c) and B (d). The p-value was calculated using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Abbreviations: BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.