The incidence of primary liver cancer ranks as the sixth most common cancer worldwide, and it is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally [1]. Individuals with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or patients with cirrhosis due to various etiologies, such as HCV infection, alcohol abuse, etc., are at high risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

The incidence of HCC in Taiwan has declined over the past 40 years. It was the leading cancer in males and third in females between 1998 and 2002. By 2019, it had dropped to fourth and sixth place, respectively. Although HCC remains a leading cause of cancer-related death, its mortality ranking has decreased from first to second place since 2010 [2].

The BCLC staging system is currently the most widely used framework for HCC [3], and serves as the treatment guidelines by both European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and American Association for the Study of the Liver (AASLD) [4,5]. It incorporates tumor size and number, liver function reserve, and patient performance status, providing strong prognostic value. Moreover, it recommends treatment modalities tailored to each BCLC substage. Specifically, for BCLC stage 0 (very early stage) and A (early stage), curative treatments, such as surgical resection, liver transplantation, and locoregional therapies, particularly radiofrequency ablation, are recommended. For BCLC stage B (intermediate stage), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is advised. Systemic therapies are suggested for BCLC stage C (advanced stage), while best supportive care is recommended for BCLC stage D (terminal stage).

However, discrepancies exist in treatment strategy between the BCLC staging system and HCC treatment guidelines in several Asian countries, including Taiwan [6–11]. Generally, medical professionals in many Asian countries tend to adopt a more aggressive approach, favoring surgical resection as the initial treatment modality for eligible patients. A previous study demonstrated significant variations in the selection of initial treatment modalities for each BCLC stage in real-world clinical practice at the local hospital level across different countries [12].

Previous studies analyzing initial treatment modalities based on the BCLC staging system were primarily limited to single-center or local hospital settings [12–14]. The aim of this study was to investigate the nationwide distribution of initial treatment modalities and assess their impact on patient survival in Taiwan.

2Patients and Methods2.1Patients and data collectionData on patients with HCC (ICD-9 code 155, or ICD-10 code C22) were retrieved from the Taiwan Cancer Registry (TCR) database [15,16]. Established in 1979, the TCR is a comprehensive, nationwide, population-based registry that collects information on newly diagnosed cancer cases from hospitals with a capacity of 50 beds or more, ensuring high-quality data completeness. Since 2002, the registry has maintained a long-form database that records cancer staging, detailed treatment modalities, and tumor recurrence data. Starting in 2011, the registry expanded to include up to 114 data items and collected detailed HCC-related site-specific factors (SSF). These include initial treatment modalities, serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), creatinine, total bilirubin, prothrombin time, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), antibody to HCV (anti-HCV), Child-Pugh classification, presence of liver cirrhosis, and BCLC staging. BCLC staging data have been registered since 2007 and became an official item since 2011. As a result, this study focused on HCC patients diagnosed between 2011 and 2019, a period during which more comprehensive clinical information was available for analysis.

The study collected relevant demographic and clinical data, including age, gender, HBsAg, anti-HCV, AFP levels, Child-Pugh classification, history of smoking, alcohol consumption, and BCLC stage.

Using the nationwide database, we examined the overall and stage-specific proportions of treatment modalities across BCLC stages, secular trends in the use of distinct treatment modalities within each BCLC stage, and the impact of these modalities on HCC survival during study periods in Taiwan. The Taiwan Cancer Registry (TCR) typically has a 2–3 years delay between diagnosis and complete data availability due to extensive case abstraction and quality assurance procedures. This includes reviewing pathology, imaging, and medical records across reporting hospitals. Such delays are common in population-based registries and reflect efforts to ensure data completeness and accuracy. Survival status was obtained from the National Mortality Database, and HCC survival was calculated and analyzed by linking and merging data from the TCR and the mortality database.

2.2Statistical analysisDemographic and clinical characteristics were expressed as percentages or mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test, whereas continuous variables were compared using Student's t-test. Univariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model for all variables, and potential prognostic factors identified in the univariate analysis were selected for multivariate analysis to assess their independent prognostic significance for overall survival. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the analysis. Furthermore, the study investigated long-term secular trends of individual factors.

2.3Ethical statementPatient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Health Research Institutes (protocol code: EC1070503-E)

3Results3.1Overall survival based on BCLC stage and treatment modalitiesA total of 73,817 HCC cases diagnosed between 2011 and 2019 were identified and included from the TCR database. Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with HCC. Fig. 1 shows the overall survival of HCC stratified by BCLC stage. The distribution of HCC cases across BCLC stages 0 to D was 9.0 %, 34.2 %, 21.5 %, 27.2 % and 8.2 %, respectively. The overall survival rates of HCC patients varied significantly across BCLC stages, with 5-year survival rates of 70 %, 58 %, 34 %, 11 %, and 4 % for BCLC stages 0, A, B, C, and D, respectively (p < 0.01). The median survival durations for BCLC stages 0, A, B, C, and D were 9.7, 6.3, 2.7, 0.6, and 0.2 years, respectively. When overall survival was analyzed by treatment modality, the highest survival rates were observed in patients who underwent liver transplantation, followed in descending order by surgical resection, locoregional ablation, TACE, radiotherapy, and targeted therapy, with significant differences (p < 0.01).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan, 2011–2019 (n = 73,817).

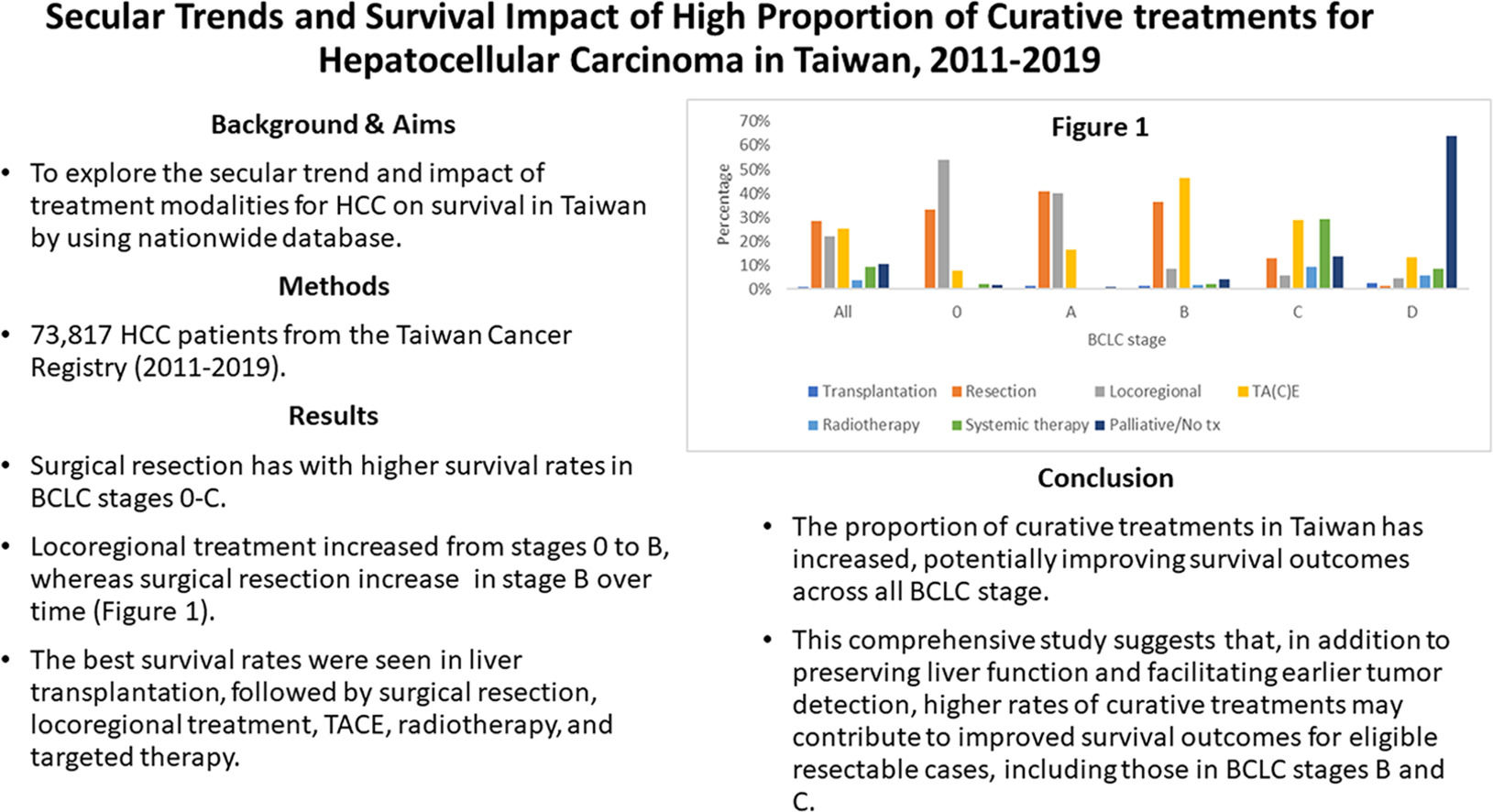

A total of 142 HCC cases (0.2 %) were excluded due to undefined treatment modalities. Additionally, treatment modalities with fewer than 50 cases within each BCLC stage were excluded from the analysis. Fig. 2 shows the distribution of treatment modalities overall and across BCLC stages 0 to D. In total, the number of HCC cases receiving liver transplantation, resection, locoregional treatment, TACE, radiotherapy, systemic therapy, and palliative treatments were 771 (1.0 %), 20,896 (28.3 %), 16,391 (22.2 %), 18,519 (25.1 %), 2641 (3.6 %), 6879 (9.3 %), and 7578 (10.3 %), respectively.

Distribution of treatment modalities by BCLC stage. Surgical resection was the most common treatment overall, followed by locoregional therapy and TACE. The predominant treatments by stage were: locoregional therapy (stage 0), resection (stage A), TACE (stage B), systemic therapy (stage C), and palliative care (stage D).

In BCLC stage 0, the most commonly used treatment modality was locoregional treatment (n = 3593, 54.1 %), followed by resection (n = 2205, 33.2 %), TACE (n = 520, 7.8 %), systemic treatment (n = 146, 2.2 %) and palliative care (n = 102, 1.5 %). For BCLC stage A, the most commonly used treatment modality was surgical resection (n = 10,323, 40.9 %), followed by locoregional treatment (n = 10,099, 40.0 %), TACE (n = 4134, 16.4 %), liver transplantation (n = 281, 1.1 %), palliative care (n = 238, 0.9 %) and radiotherapy (n = 136, 0.5 %). In BCLC stage B, TACE was the most commonly utilized treatment (n = 7320, 46.2 %), followed by resection (n = 5740, 36.2 %), locoregional treatment (n = 1310, 8.3 %), palliative care (n = 637, 4 %), systemic therapy (n = 356, 2.2 %), radiotherapy (n = 252, 1.6 %) and liver transplantation (n = 203, 1.3 %). In BCLC stage C, the most commonly administered treatment was systemic therapy (n = 5826, 29.1 %), followed by TACE (n = 5733, 28.7 %), palliative care (n = 2728, 13.6 %), resection (n = 2551, 12.8 %), radiotherapy (n = 1886, 9.4 %), and liver transplantation (n = 90, 0.5 %). For BCLC stage D, the most commonly administered treatment was palliative care (n = 3873, 64.0 %), followed by TACE (n = 812, 13.4 %), systemic therapy (n = 523, 8.6 %), radiotherapy (n = 339, 5.6 %), locoregional treatment (n = 262, 4.3 %), and liver transplantation (n = 158, 2.6 %).

Significant secular changes in the use of various treatment modalities were observed between 2011 and 2019. Overall, the proportions of patients receiving surgical resection, locoregional treatment, and systemic treatment increased from 28.0 % to 30.9 %, from 16.8 % to 23.3 % and from 6.9 % to 10.5 %, respectively (all p values for linear trend <0.01). In contrast, the use of TACE and palliative treatment declined from 30.1 % to 22.3 % and from 13.3 % to 8.1 %, respectively (all p values for linear trend <0.01).

3.3Secular change of treatment modalities based on BCLC stageFig. 3 illustrates secular trends in the use of different treatment modalities for each BCLC stage from 2011 to 2019. In stage 0 (Fig. 3a), the proportion of patients receiving locoregional treatment increased from 44.5 % to 56.8 %, while the use of TACE declined from 11.6 % to 6.3 % (all p values for linear trend <0.01). In stage A (Fig. 3b), the proportion of patients receiving locoregional treatment increased from 31.2 % to 41.2 %, while the use of TACE has declined from 24 % to 11.7 % (all p values for linear trend <0.01). In stage B (Fig. 3c), the use of resection and locoregional treatment increased from 33.1 % to 43.3 % and from 6.4 % to 8.3 %, respectively, while the proportion receiving TACE decreased from 49.2 % to 43.3 % (all p for linear trend < 0.01). In stage C (Fig. 3d), the use of systemic treatment increased from 21 % to 37.2 % (all p values for linear trend <0.01). For stage D (Fig. 3e), palliative care remained the primary treatment approach, with no significant secular changes observed in the distribution of treatment modalities.

Secular changes in the use of various treatment modalities by BCLC stage, 2011–2019. In stage 0 (a), the use of locoregional therapy increased from 44.5 % to 56.8 %, while the use of TACE decreased from 11.6 % to 6.3 %. In stage A (b), locoregional therapy rose from 31.2 % to 41.2 %, and TACE declined from 24.0 % to 11.7 %. In stage B (c), surgical resection and locoregional therapy increased from 33.1 % to 43.3 % and from 6.4 % to 8.3 %, respectively, while TACE decreased from 49.2 % to 43.3 %. In stage C (d), systemic therapy increased from 21.0 % to 37.2 %. All p-values for linear trends were < 0.01. In stage D (e), no significant secular changes were observed in the distribution of treatment modalities.

Fig. 4 shows the significant impact of different treatment modalities on survival across BCLC stages. In stage 0 (Fig. 4a), resection was associated with higher survival rates compared to locoregional treatment and TACE (all p < 0.01). In stage A (Fig. 4b), liver transplantation and resection showed superior survival outcomes compared to locoregional treatment and TACE (all p < 0.01). For stage B (Fig. 4c), liver transplantation and resection exhibited better survival rates than locoregional treatment and TACE (all p < 0.01). In stage C (Fig. 4d), liver transplantation, resection and locoregional treatment were associated with improved survival compared to TACE and systemic treatments (all p < 0.01). In stage D (Fig. 4e), liver transplantation presented the highest survival rates among all treatment modalities (p < 0.01).

Survival rates by treatment modality and BCLC stage. In stage 0 (a), surgical resection was associated with higher survival rates compared to locoregional therapy and TACE (p < 0.01). In stage A (b), both liver transplantation and resection demonstrated superior survival outcomes compared to locoregional therapy and TACE (p < 0.01). In stage B (c), liver transplantation and resection were associated with better survival rates than locoregional therapy and TACE (p < 0.01). In stage C (d), liver transplantation, resection, and locoregional therapy showed improved survival compared to TACE and systemic therapy (p < 0.01). In stage D (e), liver transplantation resulted in the most favorable survival rates among all treatment modalities (p < 0.01).

The TCR System plays an important role in offering valuable data on cancer incidence and registration in Taiwan. Over the past 40 years, the system has evolved significantly, with the long-form database now recording detailed cancer site-specific factors since 2011, which aids in improving cancer care and treatment outcomes. The importance of the TCR System lies in its capacity to support healthcare professionals and researchers in enhancing cancer care, treatment outcomes and targeted cancer prevention and control strategies [15,16].

Our study demonstrated a notable improvement in overall survival rates for HCC patients in Taiwan compared to earlier periods, during which the 5-year survival rates were historically below 20 % [13,14,17]. Enhanced survival outcomes are primarily attributed to better preserved liver function, earlier detection of tumors, and improved management strategies [18,19]. When comparing median survival durations from our analysis to the 2022 EASL guidelines, outcomes matched expected targets across all BCLC stages except stage C. The recent adjustment of median survival for BCLC stage C to two years in the EASL guidelines likely reflects advancements from clinical trials involving new therapeutic agents and revised criteria emphasizing preserved liver function. However, limited real-world studies currently support this updated standard, warranting further investigation into its appropriateness.

The distribution of treatment modalities for HCC varies globally [12]. In Taiwan, surgical resection remains the most commonly utilized treatment, followed by TACE and locoregional therapy. Over recent decades, the proportion of curative treatments has risen, whereas the use of TACE has declined [12,14] . Notably, treatment approaches for each BCLC stage in Taiwan differ significantly from those reported in other countries, where studies frequently rely on data from single, prominent hospitals, potentially introducing selection bias [12]. Our study, using comprehensive nationwide data from Taiwan, provides a more representative assessment of treatment modalities and their impact on patient survival.

The limited number of liver transplantations is primarily due to the scarcity of available living donors. For patients in BCLC stages B or C, successful downstaging using other HCC treatments may increase their eligibility for transplantation, thus potentially improving survival outcomes [20,21].

Previous studies indicate that RFA provides survival outcomes comparable to surgical resection for BCLC stage 0 patients [22–24], with a recent randomized controlled trial showing no significant differences in recurrence-free or overall survival between these treatments [25]. Our findings revealed a higher utilization of locoregional therapies in stage 0 compared to stage A in Taiwan. These treatments are associated with superior post-treatment quality of life compared to surgical resection [26]. Microvascular invasion is a significant factor for disease recurrence and survival after resection, with tumors larger than 3.5 cm posing a significantly higher risk [27]. In BCLC stage 0, the estimated risk of microvascular invasion is below 15 % [28]. Patients in this category may achieve favorable outcomes with locoregional therapies. Notably, the use of locoregional treatment in stage A patients in Taiwan (40 %) substantially exceeds that reported in other countries (16 %). High proportions of patients undergoing curative treatments in stages 0 and A are critical quality indicators in Taiwan, reflecting effective internal monitoring of cancer care quality and successful strategies for early detection and active surveillance, resulting in stage migration from stages A and B to stage [7,8,17,29,30].

Previous studies have consistently shown that surgical resection leads to significantly better survival outcomes compared to non-curative treatments like TACE in patients with BCLC stage B [31,32]. Consequently, several Asian guidelines advocate surgical resection as a primary treatment modality for this group [6–11]. In Taiwan, the proportion of patients undergoing surgical resection in BCLC stage B (33 %) notably exceeds that observed internationally (19 %) [12]. Taiwanese clinicians prioritize assessing tumor resectability, selecting patients who typically present with limited tumor numbers confined to one hepatic lobe and preserved liver function. Given these considerations, surgical intervention can offer enhanced survival or even curative potential compared to TACE. Thus, the current BCLC guideline recommending TACE alone for stage B may benefit from revision, adopting a more nuanced approach that subdivides stage B and tailors treatments accordingly.

In BCLC stage C, the utilization of systemic therapies increased by 16.2 % during the study period. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) program began reimbursing sorafenib and lenvatinib as first-line systemic treatments in 2012 and 2020, respectively, with regorafenib and ramucirumab approved as second-line treatments after sorafenib failure since 2019 and 2021. Although only 12.8 % of stage C patients underwent surgical resection, they demonstrated improved survival outcomes. These findings align with previous studies [33,34], highlighting that surgery may be beneficial in selected patients with locally advanced HCC, particularly those exhibiting subsegmental vascular invasion and preserved liver function.

Patients with BCLC stage D typically have a median survival of approximately 3 months, emphasizing the importance of palliative and symptomatic management. Liver transplantation remains the optimal curative treatment for patients with HCC who meet the Milan or UCSF criteria, as it addresses both tumor eradication and underlying liver dysfunction. However, due to the scarcity of deceased donor organs in Taiwan, expanding the use of living-donor liver transplantation is essential [8].

In limitations, while the TCR is a comprehensive, nationwide registry suitable for large-scale analysis, it lacks the clinical depth found in hospital-based studies or randomized controlled trials. Moreover, comprehensive data on patients’ disease history, concurrent illnesses, and antiviral treatments for HBV or HCV, which are known to influence HCC outcomes, are not consistently recorded. In contrast, hospital-based cohorts and randomized controlled trials offer richer clinical and longitudinal data, enabling better adjustment for confounders and clearer interpretation of treatment intent and response. Additionally, the TCR relies on ICD coding, which may introduce disease misclassification.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, this study utilizes nationwide data to generate representative results for the entire population of Taiwan. Taiwan has demonstrated superior survival outcomes compared to other countries, achieving the objectives outlined in the 2022 BCLC treatment guidelines. This comprehensive study suggests that, in addition to preserving liver function and facilitating earlier tumor detection, higher rates of curative treatments have likely contributed to improved survival in eligible resectable cases, including those in BCLC stages B and C. Additionally, consistent governmental support for healthcare policies has played a critical role in enhancing survival outcomes among HCC patients in Taiwan. These findings indicate that the current BCLC practice guidelines may not fully reflect real-world treatment success, and revisions may be warranted to better accommodate diverse clinical practices and outcomes.

FundingThis research was funded by the Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan, grant numbers: A1081116 and A1101117. The content of this research may not represent the opinion of the Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan.

Authors’ contributionsStudy concept and design: Sheng-Nan Lu; Acquisition of data: Chien-Hung Chen, Tsang-Wu Liu, Yi-Hsiang Huang, Jui-Ting Hu, Gar-Yang Chau, Kuo-Hsin Chen, Chun-Ju Chiang, Chih-Che Lin; Analysis and interpretation of data: Kwong-Ming Kee, Tsang-Wu Liu, Yi-Hsiang Huang, Chien-Fu Hung, Tsang-En Wang, Shiu-Feng Huang; Drafting of the manuscript: Kwong-Ming Kee, Bing-Shen Huang, Hui-Ju Ch’ang, Hui-Ping Tseng; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Sheng-Nan Lu, Kwong-Ming Kee. Statistical analysis: Sheng-Nan Lu, Hsiu-Ying Ku

Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

None.

Nil.