Background and aims. There are certain areas of uncertainty regarding the best therapeutic approach in patients diagnosed with Wilson Disease (WD). Our aim was to assess treatment response to different therapies in a cohort of WD patients followed in a single center.

Material and methods. This is an observational, descriptive study in which clinical, laboratory and imaging data are reviewed in a series of 20 WD patients with a median follow-up of 14 years. Type of presentation, treatment used, biochemical and copper homeostasis parameters were elicited.

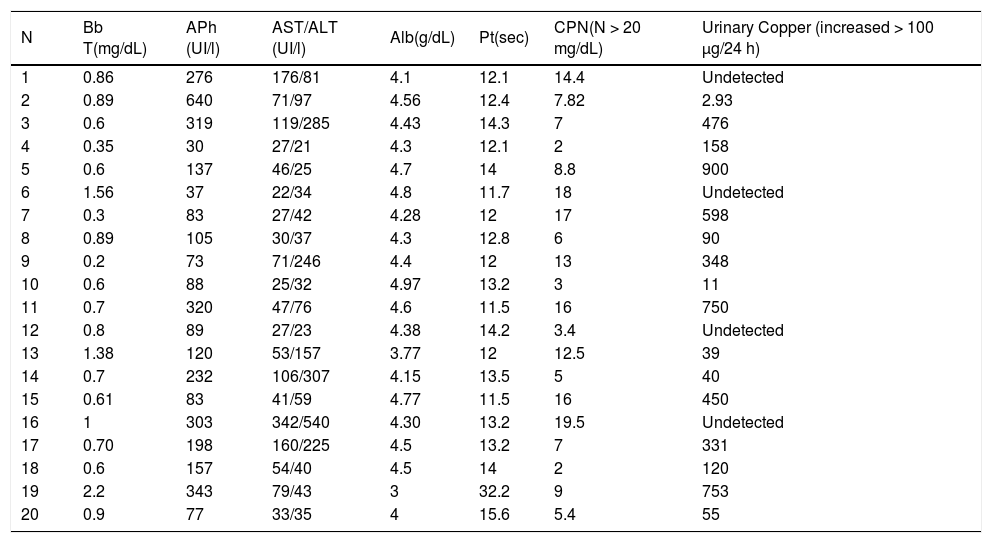

Results. Median age at diagnosis was 22 years. The most frequent form of presentation was hepatic (n = 10, 50%; mean age: 21.5 years), followed by neurological (25%; mean age: 34.5 years) and mixed (15%). The initial treatment in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients at diagnosis was d-penicillamine in 90% and Zinc (Zn) in 10%, respectively. Patients who were maintained on d-penicillamine for the whole period had complete biochemical normalization (baseline ALT: 220 IU/l; last follow up 38 IU/l). In contrast, patients in whom d-penicillamine was switched to Zn, irrespective of the cause, did not show a complete biochemical remission (baseline ALT: 100 IU/l vs. 66 IU/l at last follow-up).

Conclusions. Treatment was found to be effective in most cases regardless of the drug used. However, side effects were common in those treated with d-penicillamine agents, and required switching to zinc. Therapy with zinc was well tolerated and appeared to have a good efficacy. However, in 33%, a complete normalization of liver enzymes was never reached.

Wilson ’s disease (WD) was described by S.A. Kinnier Wilson in 1912.1 It is an inborn error of copper metabolism, of recessive autosomal inheritance, produced by the mutation of gene ATP7B, located in chromosome 13.2-6 It is characterized by a progressive accumulation of copper in the organism, mainly in the liver and lentiform nuclei, giving rise to hepatic and neurological manifestations, respectively.7 Other regions of copper deposit are the corneas (Kayser-Fleischer ring) and kidneys (Fanconi syndrome and distal tubular acidosis).8 The clinical manifestations of the disease are thus very variable, depending on the affected organ and on the seriousness of the lesions.9-12 D-penicillamine, the treatment of choice is a copper chelator that has the disadvantage of not being tolerated by many patients. In 1969, trientine was introduced as an alternative chelator.13,14 While these two agents continue to be the chelating agents of reference, zinc (Zn) has become an alternative in asymptomatic or presymptomatic patients or as maintenance therapy after an initial treatment with chelators.8,15,16 Zn interferes with the absorption of copper in the gastrointestinal tract, and it also induces enterocytes to produce metallothionein, a cysteine-rich protein that acts as an endogenous copper chelator. Moreover, it is possible that zinc acts by increasing the levels of liver cell metallothionein.17 Several but not all studies have shown that it has a good efficacy profile.18,19 However, in a recent large multicenter study, Zn monotherapy was not as effective as chelating agents in the treatment of Wilson disease.20 The combination of Zn with a copper chelator has been recommended in patients with severe hepatic failure at clinical presentation,21 but no rigorously-designed studies have been carried out yet.

The aim of our study was thus to evaluate the response to different therapies in a cohort of patients diagnosed of Wilson disease and followed in a single center for a long period of time (1975-2010).

Material and MethodsThis is an observational, descriptive study in which clinical, laboratory and imaging data, as well as response to treatment, are reviewed in a series of 20 patients with WD followed for a mean period of 14 (range 2-34) years. In all the cases, the personal and family history were elicited, as were the date of diagnosis of the disease, the type of presentation and the patient's baseline status at diagnosis (based on the clinical presentation and complementary examinations), the type of treatment used and the biochemical parameters, as well as the parameters of copper homeostasis and metabolism. The diagnosis of WD was done by combining clinical criteria, such as symptoms of liver and/or neurological involvement, and the presence of the Kayser-Fleischer ring (K-F); analytical criteria, including copper metabolism (serum ceruloplasmin under 20 mg/dL and 24-h urine copper > 100 μg) and liver histology (including the determination of the copper concentration in the liver parenchyma).

The study of the specific mutation analysis of WD is currently underway.

A written informed consent form approved by the local ethic committee was used.

For the statistical analysis, the SPSS v.17.0 software was used. Continuous variables are presented as median and range.

ResultsDemographic characteristicsThe study population included 20 patients (13 men) with a median age at diagnosis of 22 years (range: 6-50 years). Of the 20 patients, 55% (11 patients) had comorbidities, including arterial hypertension (n = 1), diabetes mellitus (n = 1), and dyslipidemia together with fatty liver (30%). More than half of the patients (60%) had a family history of WD (mostly siblings).

Clinical presentation and diagnosisThe most frequent form of presentation was hepatic (n = 10, 50%), followed by neurological (25%) and mixed (15%). In 10% of the patients, the diagnosis was done through family screening (Tables 1 and 2).

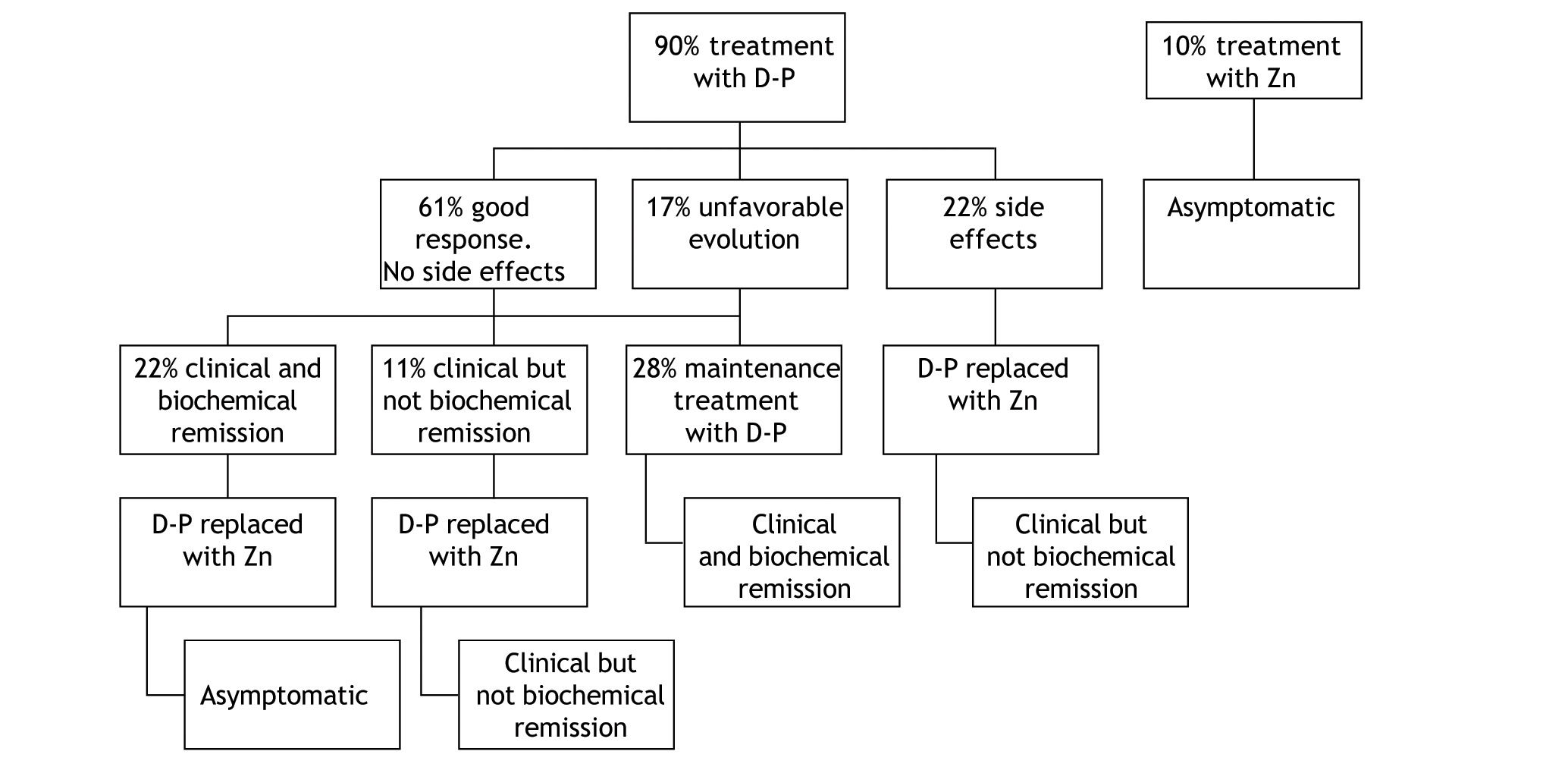

| Patient (n)/Sex | Age at onset (years) | Age at diagnosis (years) | Initial presentation | Clinical signs | Outcome | Liver biopsy | Comorbidity | Family history | Mutation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WD | Others | |||||||||

| 1/F | 8 | 35 | Combined | Elevated serum aminotransferases, hepatomegaly, parkinsonian syndrome | BR. Neurological disease remission. Mild psychiatric symptoms | Mild steatosis. No distinctive pathological WD changes. | Celiac disease | One brother with WD with tremor and mild liver involvement | ND | DR15, DR13, DR52, DR51, D16 |

| 2/M | 5 | 29 | Neurologic | Elevated serum aminotransferases, choreiform movements | Partial clinical neurological remission. Persistence of elevated serum aminotransferases | Minimal histological inflammatory changes. Copper 2057 mcg/g. Orcein and rodhamine positive | Hypertension | One sister with WD with mild neurological, psychiatric, and liver involvement | ND | ND |

| 3 /M | 7 | 7 | Hepatic | Elevated serum aminotransferases, hepatomegaly | Dystonia | Severe steatosis with periportal fibrosis areas suggestive of cirrhosis progression Copper 405 mcg/g. | Classic migraine | - | ND | ND |

| 4/F | 9 | 9 | Hepatic | Hepatomegaly, migraine headaches, dystonia | No liver involvement. Clinical neurologic improvement. Mild psychiatric symptoms. Two pregnancies | Active chronic hepatitis | One brother with psychiatric symptoms under study | ND | ND | |

| 5/F | 21 | 22 | Neurologic | Dystonia, psychiatric symptoms | Mild clinical neurological improvement | - | - | One sister with screen-diagnosed WD | ND | ND |

| 6/M | 30 | 44 | Hepatic | Elevated serum aminotransferases | BR | - | DM, dyslipidemia | - | ND | ND |

| 7/M | 33 | 35 | Neurologic | Parkinsonian syndrome | Clinical neurological remission with mild residual tremor. One asymptomatic son | - | Dyslipidemia. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome | Maternal aunt with similar clinical features, under study | ND | ND |

| 8/M | 38 | 40 | Neurologic | Elevated serum aminotransferases, dystonia. | BR. Clinical remission | Macronodular cirrhosis. Orcein and rodhamine positive | - | Two maternal cousins with WD | ND | ND |

| 9/F | 6 | 6 | Hepatic | Asymptomatic (screening) | An episode of acute hepatitis and intravascular hemolysis at age 15. At age 31, mild tremor and mild psychiatric symptoms. Bad compliance | Active chronic hepatitis | HIV. Liver hemangioma. Osteoporosis | One sister with WD | Positive | ND |

| 10/M | 3 | 7 | Hepatic | Elevated serum aminotransferases | BR. Asymptomatic. | Active chronic hepatitis with mild activity | - | Cousin with WD. Brother under study | ND | ND |

| 11/M | 9 | 10 | Hepatic | Asymptomatic (screening) | BR. Subsequent transaminases elevation and liver steatosis. Bad treatment compliance | Active chronic hepatiti: Copper 593 mcg/g. Orcein and rodhamine positive | Dyslipidemia. Proximal tubular dysfunction and hypercalciuria | One twin brother with WD and similar clinical features | ND | HFE gene C282Y/H63D |

| 12/F | 22 | 23 | Hepatic | Asymptomatic, elevated serum aminotransferases | Stable compensated cirrhosis. Two pregnancies. | Liver cirrhosis. Copper 1,200 mcg/g. Orcein and rodhamine positive | One sister liver-transplanted due to fulminant hepatitis of unknown cause (WD not discarded) | ND | ND | |

| 13/M | 9 | 33 | Hepatic | Elevated serum aminotransferases | Liver function tests improvement without full remission | Diffuse liver steatosis. Copper 781 mcg/g | Dyslipidemia | - | ND | ND |

| 14/F | 11 | 13 | Hepatic | Mild hyper-transaminasemia and diffuse abdominal pain | BR. Asymptomatic. One pregnancy. One abortion. | Hepatocellular fatty degeneration. Portal fibrosis | Dyslipidemia | - | ND | ND |

| 15/M | 22 | 22 | Hepatic | Elevated serum aminotransferases and diffuse abdominal pain | Liver function tests improvement full remission | Minimal inflammatory without changes | - | - | ND | ND |

| 16/M | 18 | 18 | Hepatic | Asymptomatic, elevated serum aminotransferases | Liver function tests improvement without full remission | Minimal inflammatory changes and fatty infiltration. Copper 600 mcg/g. Orcein and rodhamine positive | - | One sister with WD. Father with liver disease under study | ND | HFE gene, negative |

| 17/M | 9 | 10 | Hepatic | Elevated serum aminotransferases, mild abdominal pain and asthenia | Liver function tests improvement without full remission | Active chronic hepatiti: Copper 544 mcg/g | Dyslipidemia. Proximal tubular dysfunction and hypercalciuria | One twin brother with WD and similar clinical features | ND | HFE gene C282Y/H63D |

| 18/M | 30 | 31 | Neurologic | Severe dystonic and parkinsonian syndrome, elevated serum aminotransferases | Unfavourable prognosis. Clinical neurological deterioration. No treatment response | - | - | - | ND | ND |

| 19/F | 22 | 23 | Hepatic | Hydropic decompensation in advanced cirrhosis | Liver-transplanted with good evolution | Micronodular liver cirrhosis | Ulcerative colitis | - | ND | ND |

| 20/M | 38 | 39 | Combined | Mild dystonic and ataxic syndrome. Elevated serum aminotransferases | Near complete remission of neurological clinic. Compensated cirrhosis | Macronodular liver cirrhosis. Orcein and rodhamine positive | - | - | ND | ND |

F: female. M: male. BR: biochemical remission. ND: not done. DM: diabetes mellitus.

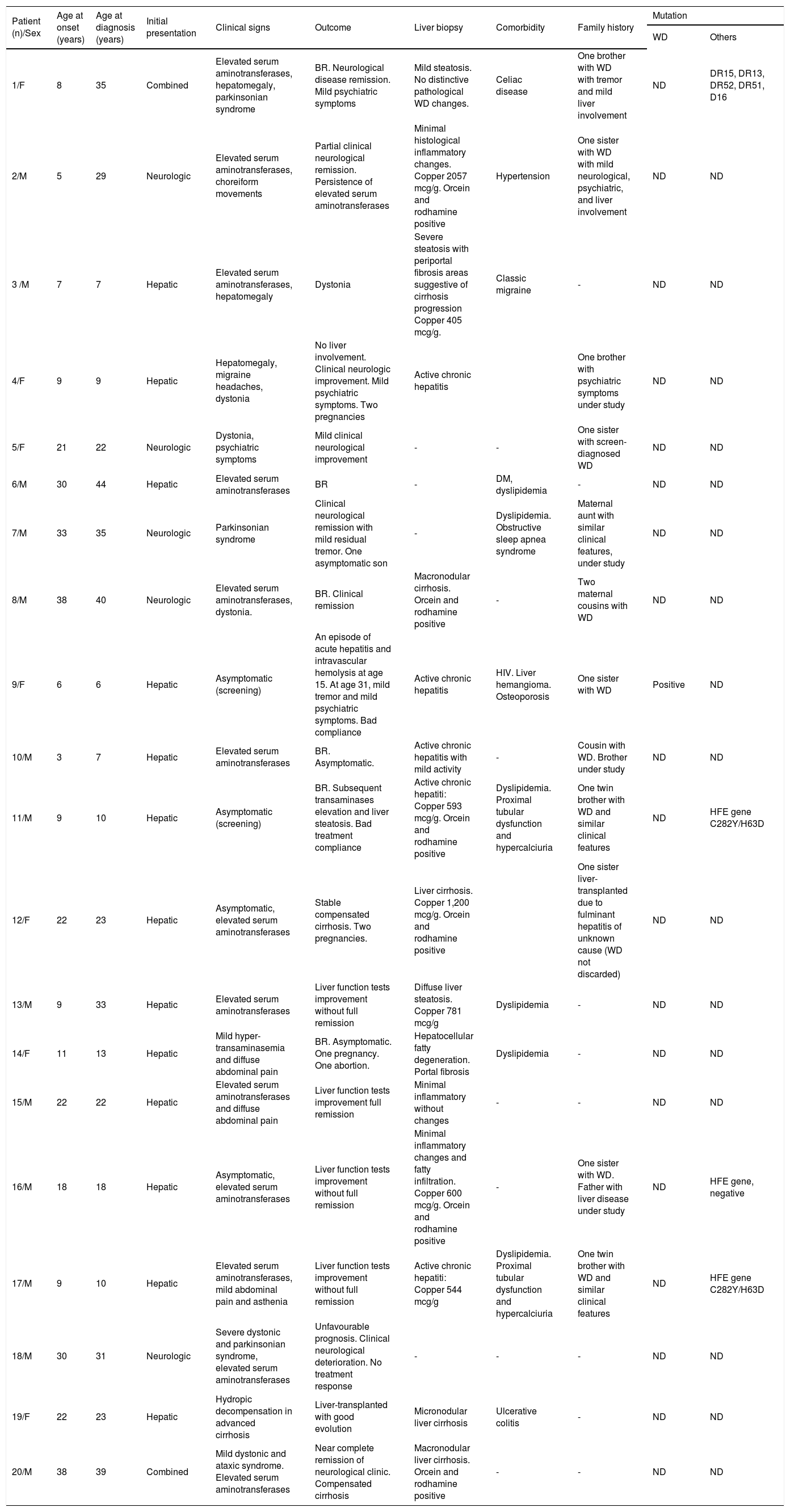

| N | Bb T(mg/dL) | APh (UI/l) | AST/ALT (UI/l) | Alb(g/dL) | Pt(sec) | CPN(N > 20 mg/dL) | Urinary Copper (increased > 100 μg/24 h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.86 | 276 | 176/81 | 4.1 | 12.1 | 14.4 | Undetected |

| 2 | 0.89 | 640 | 71/97 | 4.56 | 12.4 | 7.82 | 2.93 |

| 3 | 0.6 | 319 | 119/285 | 4.43 | 14.3 | 7 | 476 |

| 4 | 0.35 | 30 | 27/21 | 4.3 | 12.1 | 2 | 158 |

| 5 | 0.6 | 137 | 46/25 | 4.7 | 14 | 8.8 | 900 |

| 6 | 1.56 | 37 | 22/34 | 4.8 | 11.7 | 18 | Undetected |

| 7 | 0.3 | 83 | 27/42 | 4.28 | 12 | 17 | 598 |

| 8 | 0.89 | 105 | 30/37 | 4.3 | 12.8 | 6 | 90 |

| 9 | 0.2 | 73 | 71/246 | 4.4 | 12 | 13 | 348 |

| 10 | 0.6 | 88 | 25/32 | 4.97 | 13.2 | 3 | 11 |

| 11 | 0.7 | 320 | 47/76 | 4.6 | 11.5 | 16 | 750 |

| 12 | 0.8 | 89 | 27/23 | 4.38 | 14.2 | 3.4 | Undetected |

| 13 | 1.38 | 120 | 53/157 | 3.77 | 12 | 12.5 | 39 |

| 14 | 0.7 | 232 | 106/307 | 4.15 | 13.5 | 5 | 40 |

| 15 | 0.61 | 83 | 41/59 | 4.77 | 11.5 | 16 | 450 |

| 16 | 1 | 303 | 342/540 | 4.30 | 13.2 | 19.5 | Undetected |

| 17 | 0.70 | 198 | 160/225 | 4.5 | 13.2 | 7 | 331 |

| 18 | 0.6 | 157 | 54/40 | 4.5 | 14 | 2 | 120 |

| 19 | 2.2 | 343 | 79/43 | 3 | 32.2 | 9 | 753 |

| 20 | 0.9 | 77 | 33/35 | 4 | 15.6 | 5.4 | 55 |

Bb T: Total Bilirubin. APh: Alkaline Phosphatases. Alb: Albumin. Pt: prothrombin time. CPN: ceruloplasmin. N: Normal.

Of those with liver involvement (n = 15), the disease made its debut as acute hepatitis (altered liver function tests, asthenia and mild abdominal pain) in 4 without any prior history of liver disease. Three of these patients progressed to chronic elevation of liver function tests (chronic hepatitis) while one progressed to fulminant hepatitis that required liver transplantation. The explant showed that this was a cirrhotic patient who had developed a severe flare. In the other 3 patients (3 children aged 7, 9 and 9 years old at clinical presentation), the liver biopsy was performed 6 months after the initial rise in liver enzymes. The remaining 11 patients presented with altered liver function tests only without any clinical manifestations and in the absence of signs and symptoms suggestive of liver disease.

Fourteen patients underwent a liver biopsy at initial presentation. In seven, hepatic copper content was measured while in 7 this measurement was not performed. Of the 7 in whom it was measured, 100% had results diagnostic of WD (> 250 mcg/dry weight); of these, only five patients had stainable copper (Orcein and rodhamine positive) (Table 1). Of the remainder 7 patients, in whom hepatic copper content was not measured, stainable copper was observed in only one case.

Of those with neurological involvement, it was the first clinical presentation in 8 cases. Parkinsonism (akinetic-rigid syndrome) and dystonic syndrome were the most frequent manifestations. The mean age of presentation in these cases was 34.5 years.

A delay between clinical presentation and time of diagnosis greater than 1 year occurred in 50% of cases, particularly in those presenting with neurological symptoms.

A decrease in ceruloplasmin was seen in all cases, while an increase in urine copper was present in 50% of patients at diagnosis. The diagnosis was based on the presence of the K-F ring together with alterations in copper metabolism in 55% of the patients. In 6 cases, the diagnosis required liver copper measurement. In 80% of the patients in whom brain imaging tests (mainly MRI) were carried out, images were characteristic of the disease. Of these, 75% were patients with WD of neurological predominance.

TreatmentIn this series, the initial treatment of choice in symptomatic patients at diagnosis was d-penicillamine, which was administered in 90% of the cases (Figure 1). The remaining 10% were asymptomatic patients with normal liver enzymes in whom treatment with Zn was the first therapy.

In the group of patients that started therapy with d-penicillamine, a good response, defined as clinical and biochemical improvement and/or normalization without development of side effects occurred in 61%. This good response was more frequent in patients with hepatic presentation (93%) compared to those with neurological involvement (60%). Of all patients with neurological presentation, 2 (40%) did not respond to d-penicillamine.

Biochemical parameters at start of therapy and end-of-follow up are shown in table 1 and 2. Among those treated with d-penicillamine, ALT levels were 128 IU/l at baseline and 6 months later the values were within normal range (42 IU/l). In turn, patients who were initially treated with Zn had normal liver tests at baseline (AST 32 IU/l and ALT 36 IU/l) and these values remained similar with follow-up (27 IU/l and 30 IU/l respectively at 6 months post-Zn). Interestingly, patients who were maintained on d-penicillamine for the whole follow-up (28%) had complete biochemical normalization (mean baseline ALT: 220 IU/l; last follow up 38 IU/l). In addition, in patients who were switched to Zn after clinical and biochemical remission were obtained (22%), no changes were observed. In contrast, the patients in whom d-penicillamine was switched to Zn for sideeffects (22%) or “were changed to maintenance therapy after only clinical but not biochemical remission” (11%), did not show a complete biochemical remission (mean baseline ALT: 100 IU/l versus 66 IU/l at last follow-up).

Initial therapy with d-penicillamine was modified in 72% of the cases. In most cases (33%) it was replaced with Zn following a clinical and in most cases a biochemical remission. The second cause of treatment modification was the development of side effects, which occurred in 22% of the total of patients treated with d-penicillamine. In these cases, it was also replaced by Zn. Finally, in 3 (17%) patients (one with liver involvement and two with neurological involvement) in whom the treatment was modified, the cause was a scarce improvement or an unfavourable evolution. In these cases, the dose of d-penicillamine was increased and Zn was added. Unfortunately, no significant changes compared to the previous evolution were observed. The patient with hepatic presentation required a liver transplantation, and of the 2 patients with neurologic presentation, one worsened clinically with d-penicillamine therapy and in the remainder, no changes in clinical status were observed.

Zn therapy was hence used as first line therapy in 10% of patients (those with a normal liver panel who were asymptomatic) and as second-line therapy in 55% of patients. Treatment with Zn was well tolerated and patients only complained of mild gastrointestinal symptoms that resolved spontaneously.

DiscussionTherapy of patients with Wilson Disease is extremely rewarding, particularly if treatment is started at early stages of the disease. Diagnosis is however not straightforward in all cases, and a high degree of suspicion is required. In addition, some doubts have risen in recent years as to the best therapeutic options. Most published series are limited by either the small number of patients included or the relatively short follow up. Our center is a large tertiary hospital, reference for patients with Wilson Disease. We hence decided to retrospectively evaluate our series of patients diagnosed with Wilson Disease with the main aim of determining the type of response to therapy. The main conclusions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- •

A large proportion of patients had a family history of Wilson Disease.

- •

A long delay to reaching the diagnosis was more common in patients diagnosed in early eras, particularly in those with neurologic involvement.

- •

Most patients responded adequately to therapy, regardless of the type of drug used.

- •

Although d-penicillamine was effective it was associated with adverse side effects; in contrast, zinc was better tolerated but complete normalization of serum aminotransferases was not always achieved.

Given its genetic nature, the diagnosis in relatives of affected patients becomes easier. In our series, for instance, 60% had a family history of WD, and the diagnosis was made at presymptomatic stages. In the remaining cases, the diagnosis is based on standard recommendations. However, several series have reported a substantial delay in reaching the diagnosis, possible due to lack of awareness of this uncommon disease. In our study, which covered a long period, there was a delay in diagnosis since the initial symptoms appeared until the disease was confirmed of over 10 years in 4 patients (20%), mostly patients of the early eras. It is important to point out that those with liver involvement were diagnosed earlier than those with neurological presentation. In fact, in 53% of the patients with initial liver presentation, the diagnosis was confirmed at an age younger than 20, whereas no patient with neurological manifestations was diagnosed at this age.

Fortunately, an adequate response to treatment together with a good clinical outcome is generally the rule. In our series, the majority of cases improved with therapy, particularly those with hepatic presentation. Currently, chelating agents are recommended as initial treatment for symptomatic patients.22,23 In our series, d-penicillamine was the drug mostly used, particularly in those who were symptomatic at diagnosis. In patients at pre-symptomatic stages or on maintenance therapy, chelators or Zn are potential alternatives. In our series, therapy with Zn was started in 10% of the patients, those who were asymptomatic. Moreover, d-penicillamine was replaced by Zn in 33% of the patients who had initially started treatment with d-penicillamine and who had evolved favourably. In these patients, no clinical no biochemical changes were observed after switching one drug by the other. In contrast, patients in whom d-penicillamine was replaced by Zn due to side effects (22%) had a clinical but not biochemical remission. Whether the absence of complete liver enzyme normalization is related to Zn itself as suggested in a recent large multicenter study,20 lack of compliance or whether it is related to additional pathologies, particularly non-alcoholic steatohepatitis is unknown. In our patients, compliance was regularly confirmed by determining urine excretion of zinc and copper.

ConclusionIn conclusion, in this short series of patients with WD diagnosed over the last 30 years and treated with different approaches, treatment was found to be effective in most cases regardless of the drug used. However, side effects were common, mostly in those treated with d-penicillamine agents, and required a switch to zinc. Therapy with zinc was well tolerated and appeared to have a good efficacy. However, in 33% of patients treated with Zn, a complete normalization of liver enzymes was never reached. If these patients should be switched back to chelating agents is still a matter of debate.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare that they do not have anything to disclose regarding funding or conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript.