Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is characterized by progressive destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts [1]. Pruritus is a burdensome symptom that impairs quality of life [2,3].

Although pruritus is clinically relevant, it is often underreported [4] and not systematically assessed, despite recommendations to do so [5–7]. Even when physicians record the presence of pruritus, reported prevalence rates vary widely between 12 % and 67 % [8], and only 53–67 % of PBC patients with pruritus receive antipruritic therapy [4,7,9]. Antihistamines are frequently prescribed, despite not being recommended by current guidelines [4,5,7,9]. In the UK, only 37 %, 11 %, and 5 % of patients received guideline-recommended therapies such as cholestyramine (Prevalite Powder), rifampicin, or naltrexone, respectively [10].

For Germany, data on prevalence and management of pruritus in patients with PBC are scarce [11,12]. This analysis focuses on pruritus and compares different levels of health care within a nationwide PBC registry.

2Patients and MethodsThe German PBC registry is a real-world registry that enrolled 515 adult patients across 33 centers [13]. Private practices and non-teaching hospitals were grouped as secondary care, university hospitals were classified as tertiary care.

Pruritus was assessed by treating physicians using a four-point verbal rating scale (absent, mild, moderate, or severe pruritus) at the registry’s inclusion visit (= baseline). This manuscript reports a cross-sectional analysis of pruritus characteristics and the use of antipruritic medication at this time point.

Antipruritic medication was defined as antihistamines, cholestyramine (Prevalite Powder), bezafibrate, rifampicin, naltrexone, naloxone, sertraline, gabapentin (Neurontin), or steroid-containing ointments. However, the data do not allow for a distinction between bezafibrate use as a second-line treatment to achieve biochemical response, or as an anti-pruritic therapy, or for both purposes.

2.1StatisticsDifferences in metric items were analyzed using Mann-Whitney tests to identify significant differences (p < 0.05). For nominal items with more than two categories, Chi-square tests were used, followed by Fisher's exact tests when appropriate.

2.2Ethics approval and patient consent statementAll patients provided written informed consent. The registry was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Leipzig (vote number 003/18-ek).

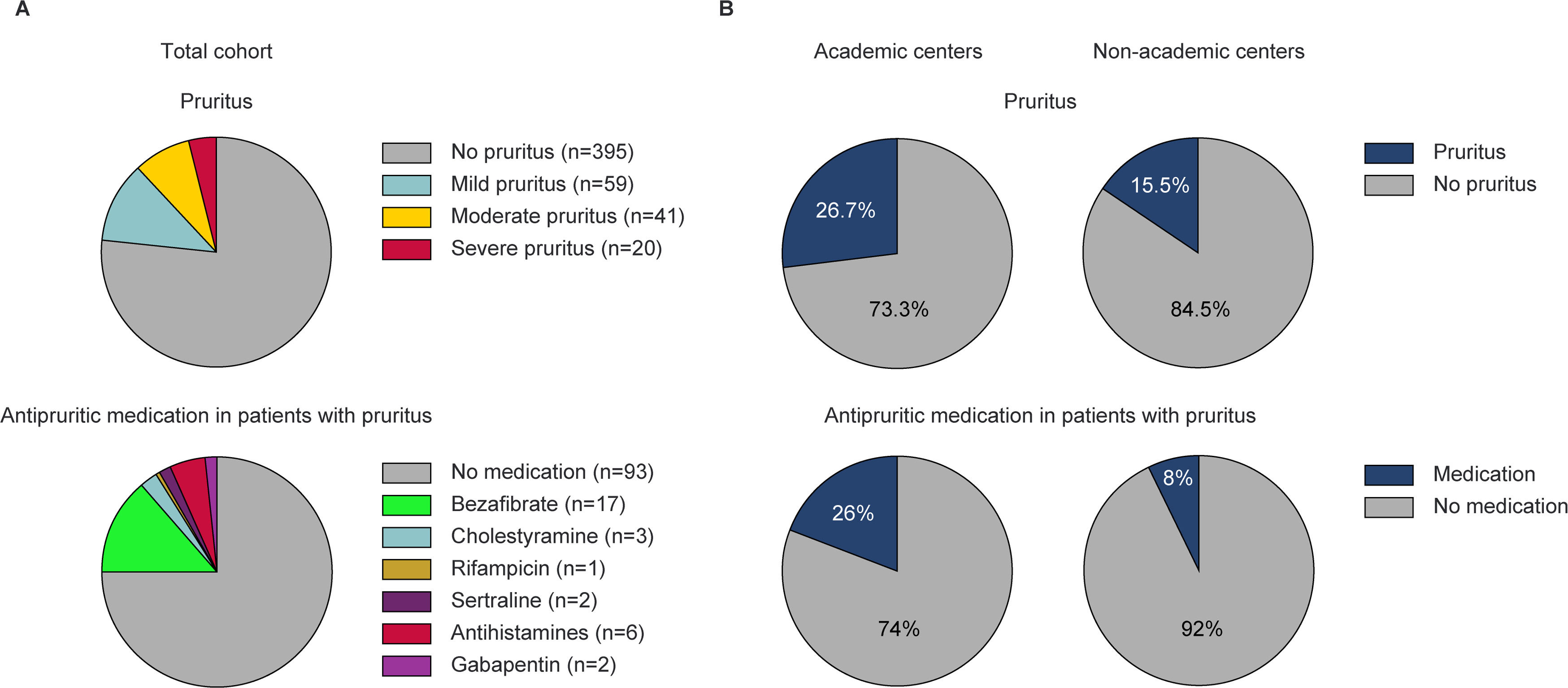

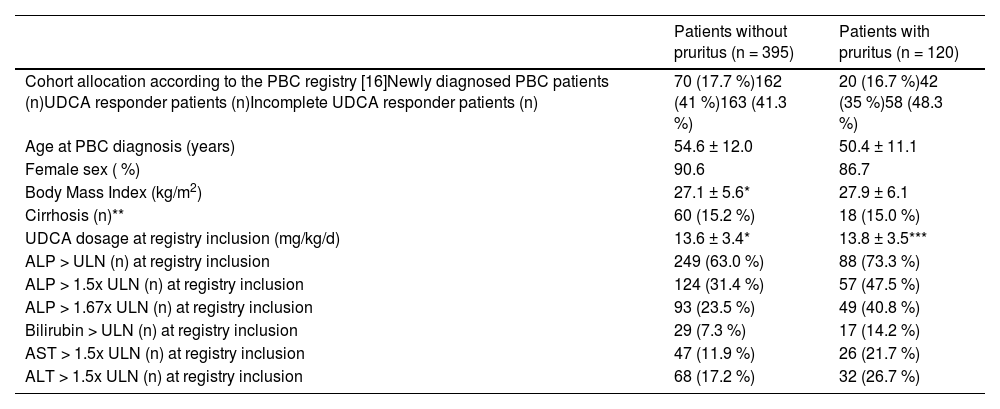

3Results3.1Baseline characteristics at registry inclusionPruritus was noted in 120/515 patients (23 %) and was classified as mild, moderate, or severe in 59 (49 %), 41 (34 %), and 20 (17 %) cases, respectively (Fig. 1A). Individuals with pruritus were younger at the time of PBC diagnosis (50.4 ± 11.1 years vs. 54.6 ± 12.0 years, p < 0.001) and reported depression more often (16/120 [13.3 %] vs. 25/395 [6.3 %], p = 0.020) compared to individuals without pruritus. Prevalence of pruritus was not associated with UDCA dose, treatment response according to Paris II criteria, alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin, or cirrhosis (Table 1).

Prevalence of pruritus and use of antipruritic medication in the total cohort, and by the level of care. (A) Prevalence of pruritus (n = 515, upper panel), and use of antipruritic medication (including patients on combination regimens) in patients with pruritus (n = 120, lower panel). (B) Prevalence of pruritus in patients treated at academic (n = 360) and non-academic centers (n = 155) (upper panels), and use of antipruritic medication in patients with pruritus treated at academic (n = 96) or non-academic centers (n = 24) (lower panels).

Baseline characteristics at registry inclusion.

| Patients without pruritus (n = 395) | Patients with pruritus (n = 120) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort allocation according to the PBC registry [16]Newly diagnosed PBC patients (n)UDCA responder patients (n)Incomplete UDCA responder patients (n) | 70 (17.7 %)162 (41 %)163 (41.3 %) | 20 (16.7 %)42 (35 %)58 (48.3 %) |

| Age at PBC diagnosis (years) | 54.6 ± 12.0 | 50.4 ± 11.1 |

| Female sex ( %) | 90.6 | 86.7 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 27.1 ± 5.6* | 27.9 ± 6.1 |

| Cirrhosis (n)** | 60 (15.2 %) | 18 (15.0 %) |

| UDCA dosage at registry inclusion (mg/kg/d) | 13.6 ± 3.4* | 13.8 ± 3.5*** |

| ALP > ULN (n) at registry inclusion | 249 (63.0 %) | 88 (73.3 %) |

| ALP > 1.5x ULN (n) at registry inclusion | 124 (31.4 %) | 57 (47.5 %) |

| ALP > 1.67x ULN (n) at registry inclusion | 93 (23.5 %) | 49 (40.8 %) |

| Bilirubin > ULN (n) at registry inclusion | 29 (7.3 %) | 17 (14.2 %) |

| AST > 1.5x ULN (n) at registry inclusion | 47 (11.9 %) | 26 (21.7 %) |

| ALT > 1.5x ULN (n) at registry inclusion | 68 (17.2 %) | 32 (26.7 %) |

Second-line therapies included UDCA plus bezafibrate in 61 patients, UDCA plus obeticholic acid (OCA) in 54 patients, and a triple combination of UDCA, bezafibrate, and OCA in 7 patients. OCA was prescribed at similar frequencies in patients with or without pruritus (17/120 [14.2 %] vs. 37/395 [9.4 %], p = 0.172).

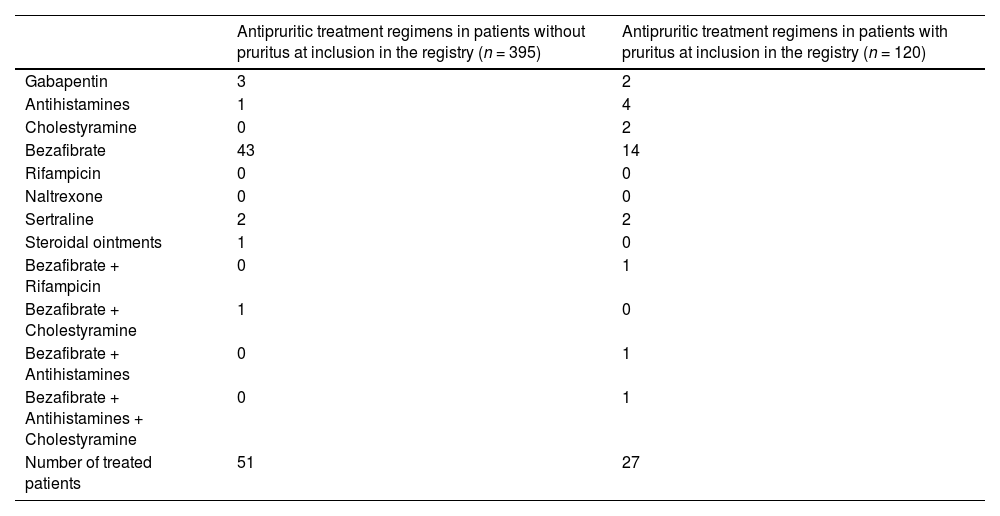

3.2Use of medications with antipruritic effectMedications with antipruritic effect were prescribed in 27/120 (22.5 %) patients with pruritus and in 51/395 (12.9 %) without. Bezafibrate was the most commonly prescribed medication with antipruritic effect in patients with pruritus (17/27 [63 %]), while all other therapies were used only in single cases (Table 2 and Fig. 1A).

Antipruritic medication prescribed in patients without and with pruritus.

61/120 (51 %) individuals with pruritus suffered from moderate or severe pruritus. Moderate or severe pruritus was associated with psoriasis (5/12 [42 %] vs. 56/503 [11 %], p = 0.008), and depression (9/41 [22 %] vs. 52/474 [11 %], p = 0.045). There was no association with other concomitant diseases (i.e. systemic sclerosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus), gender, pregnancy, body mass index, cirrhosis, UDCA response according to Paris II criteria, or treatment with OCA.

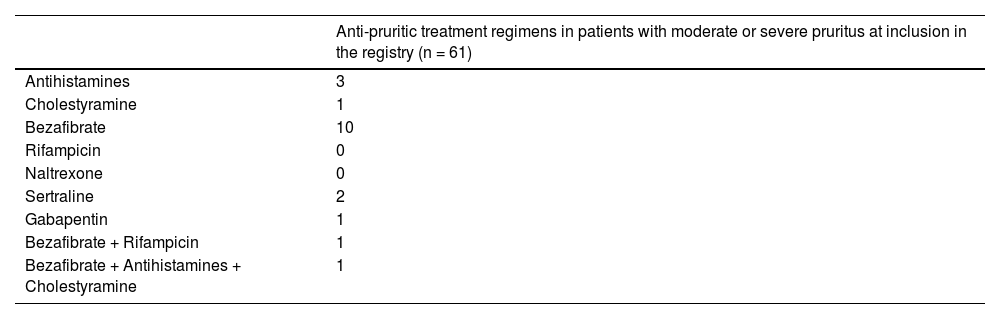

Anti-pruritic therapies were used in 19/61 (31 %) cases: 13/41 [32 %] with moderate pruritus and 6/20 [30 %] with severe pruritus. Individual treatment regimens are listed in Table 3 and were based on bezafibrate-containing therapies in 12/19 (63 %) cases.

3.4Prevalence and treatment of pruritus according to the level of healthcareThe prevalence of pruritus was higher in patients treated at tertiary (96/360 [26.7 %]) compared to those treated at secondary care (24/155 [15.5 %]) (p = 0.006), ranging from 0–86 % and 0–50 % at each care level, respectively (Fig. 1B). Patients with moderate or severe pruritus were more likely to present at the tertiary than at the secondary care centers (48/360 [13.3 %] vs. 13/155 [8.4 %], p = 0.137).

Antipruritic medications were prescribed in 68/360 (19 %) patients at tertiary centers and in 11/155 (7 %) at secondary centers (p < 0.001). Patients with pruritus were more likely to receive antipruritic medication at the tertiary than at the secondary care level (25/96 [26 %] vs. 2/24 [8 %], p = 0.098) (Fig. 1B). The percentage of patients with pruritus receiving antipruritic therapy ranged from 0 to 75 % in tertiary centers and from 0 to 50 % in secondary centers.

4DiscussionThis study underscores the burden of pruritus in patients with PBC, highlights its undertreatment, and compares prevalence and treatment approaches between tertiary and secondary care. Consistent with previous findings [4,10,14], our study observed that pruritus in PBC is more common among patients diagnosed at a younger age and those with comorbid depression. The association with younger age may reflect a greater likelihood of a ductopenic phenotype in these patients [15,16], which is linked to pruritus [17]. Regarding depression, pruritus can contribute to depressive symptoms, though the reverse is also possible [18]. Moderate to severe pruritus was associated with psoriasis in 10 % of affected individuals. In these cases, pruritus may result from the skin disease, making it difficult to distinguish from PBC-related itch and requiring different therapy.

Treating physicians reported pruritus in 23 % of patients. Reported prevalence varied widely across centers, reflecting discrepancies in detection. This aligns with UK data and may stem from differences in awareness and assessment [8]. Prevalence and intensity of pruritus were higher in tertiary than in secondary care centers, possibly reflecting more frequent referral of patients with pruritus to tertiary care. Patient preference, a higher perceived need for treatment, or the perception of more therapeutic options are potential reasons for referrals [19].

"The physician-reported pruritus prevalence in our registry (23 %) was lower than the 56 % patient-reported rate in a German survey [20]. This difference emphasizes that itch remains difficult to objectify [17]. It may also suggest that physicians understate symptom burden, possibly to avoid clinical actions such as implementing effective itch management. Similar patterns are seen in fatigue assessment, another symptom of PBC, where the absence of treatment options can lead to underreporting or downplaying [21–24].

Treatment rates suggest that pruritus is undertreated, with only 22.5 % of affected patients receiving therapy. Rates were higher in moderate or severe cases (31 % and 40 %) and more common at tertiary centers. However, under-treatment may be overestimated, as some patients might have received therapy leading to symptom resolution.

Bezafibrate was the most commonly used antipruritic medication, while guideline-recommended treatments like bile acid sequestrants and rifampicin were rarely prescribed. Limited adherence to guidelines may be due to weak supporting evidence and the off-label status of most therapies for PBC-related pruritus [25,26].

Bezafibrate, though off-label, has demonstrated efficacy as second-line treatment and antipruritic therapy [27,28]. These data are not yet reflected in current guidelines [1,6], and warrant inclusion in future updates. In our registry, the indication for bezafibrate, whether as a second-line treatment for inadequate UDCA response or specifically for pruritus, remained unclear, highlighting the need for future real-world data to distinguish between biochemical and symptomatic treatment intent.

5ConclusionsOur findings highlight the need for a sophisticated evaluation of the causes of pruritus and for improved systematic management of itch in patients with PBC across all levels of care. Ongoing education on symptoms remains crucial to ensure comprehensive PBC care.

FundingThe German PBC Cohort was supported by an unrestricted research grant of Intercept/Advanz Pharma to T.B.

Authors contributions- Conceptualization: TH, JW; - Data curation: TH, AF, KP, NKB, JW; - Formal analysis: TH, AF, JW, AEK; - Funding acquisition: TB; - Investigation: TH, TM, KS, HB, RG, GD, PAR, JMS, UN, TB, AW, SZ, MH, RG, CB, TTW, KGS, JT, RB, HG, WPH, ND, CS, ER, MM, MR, AT, UM, VK, JUM, AK, FT, CT, TB, JW, AEK; - Methodology: TH, AF, JW, AEK; - Project administration: TB, JW; - Visualization: TH; - Writing - original draft: TH, AF, AEK, JW; - Writing - review & editing: all authors.

Data availability statementAccording to the recommendations on data sharing by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), data resulting from the project will be made available to the scientific community as follows: after publication of the major results and upon reasonable request from researchers performing an individual patient data meta-analysis, individual patient data that underlie published results will be shared after de-identification. This requires approval by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the researcher requesting the data along with public registration of the meta-analysis. Summary statistics that go beyond the scope of published material will be made available to researchers for meta-analysis upon reasonable request and if the necessary data analysis is not unduly time-consuming.

JW: Lecturer and advisory board member for Intercept/Advanz Pharma, GSK, Ipsen, Gilead; TH: consulting fees of Albireo (Ipsen), Advanz; advisory board member for Advanz, Gilead, GSK; speaker’s honoraria of Ipsen; authors fee of Falk Foundation; TM: supported by the German Research Foundation Grants MU 2864/1–3 and MU 2864/3–1; KS: Receipt of speaker´s honoraria or advisory board: Gilead, Intercept/Advanz Pharma, Abbvie, Falk, Novo Nordisk, Lilly; HB: Consultant: Intercept/Advance Pharma, Ipsen; GD: Consultant / speaker: AbbVie, Advanz/Intercept, Alexion, Falk Foundation, Gilead, Novartis, Orphalan, Univar; PAR: Consulting and lectures fees: Astra Zeneca, BMS, Boston Scientific, CSL Behring, Gilead, Pfizer, Abbvie, Norgine; JMS: Consultant: Akero, Alentis, Alexion, Altimmune, Astra Zeneca, 89Bio, Bionorica, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead Sciences, GSK, HistoIndex, Ipsen, Inventiva Pharma, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals,Kríya Therapeutics, Lilly, MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Nordic Bioscience, Northsea Therapeutics, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Siemens Healthineers; Stock Options: Hepta Bio; Speaker Honorarium: Boehringer Ingelheim, Echosens, Novo Nordisk, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals; SZ: Speakers bureau and/or consultancy: Abbvie, BioMarin, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, GSK, Intercept, Ipsen, Janssen, Madrigal, MSD/Merck, NovoNordisk, SoBi, Theratechnologies; KGS: Consultant: Advance Pharma, Speaker Honorarium: AbbVie, Gilead; JT: has received speaking and/or consulting fees from Versantis, Gore, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Falk, Grifols, Genfit and CSL Behring; WPH: Consultant or Speaker Honorarium: Intercept /Advanz, Ipsen, NovoNordisk, Gilead, Abbvie, Norgine; CS: Consultant, Study support or Speaker Honorarium: Calliditas, Falk, Intercept/Advanz, Ipsen, Mirum; ER: Receipt of honoraria or consultation fees/advisory board: Abbvie, Amgen, Intercept, Medac, Merz, Norgine, Falk Foundation, Gilead, Pfizer, Repha, Takeda; AEK: Research grant: Gilead, Intercept. Speakers bureau: Abbvie, Advanz, AOP Orphan, Bayer, BMS, CMS, CymaBay, Falk, Gilead, GSK, Intercept, Ipsen, Newbridge, Novartis, Lilly, Mirum, MSD, Roche, Zambon. Consultant or Speaker Honorarium: Abbvie, Advanz, Alentis, AlphaSigma, AstraZenca, AOP Orphan, Avior, Bayer, BMS, CymaBay, Escient, Falk, Gilead, GSK, Guidepoint, Intercept, Ipsen, Mirum, Medscape, MSD, Newbridge, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Takeda, Vertex Viofor; MR: Consultant, or Speaker Honorarium: Intercept/Advanz, Gilead, Abbvie; AW: speaker honorarium: Abbvie; AT: Speaker Honorarium: Intercept/Advanz; UM: Consultant or Speaker Honorarium: CytoSorbents, Falk, Gilead, Microbiotica, Univar; VK: Consultant Astra Zeneca, Speaker’s Honoraria from AbbVie, Gilead, Falk, Mirum, Albireo/Ipsen, Merck, MedUpdate GmbH, Sanofi, CSL Behring; ER: Receipt of honoraria or consultation fees/advisory board: Abbvie, Amgen, Intercept, Medac, Merz, Norgine, Falk Foundation, Gilead, Pfizer, Repha, Takeda; FT: Research grant: AstraZeneca, MSD, Gilead. Speakers bureau: Gilead, Abbvie, Falk, Merz, Orphalan, Advanz. Consultant: AstraZeneca, Gilead, Abbvie, Alnylam, BMS, Intercept / Advanz, MSD, GSK, Ipsen, Pfizer, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi; CT: Receipt of honoraria or consultation fees/advisory board: Intercept/Advanz Pharma; TB: Receipt of grants/research supports: Abbvie, BMS, Gilead, MSD/Merck, Humedics, Intercept, Merz, Norgine, Novartis, Orphalan, Sequana Medical; Receipt of honoraria or consultation fees/advisory board: Abbvie, Alexion, Albireo, Bayer, Gilead, GSK, Eisai, Enyo Pharma, HepaRegeniX GmbH, Humedics, Intercept, Ipsen, Janssen, MSD/Merck, Novartis, Orphalan, Roche, Sequana Medical, SIRTEX, SOBI, and Shionogi; Participation in a company sponsored speaker’s bureau: Abbvie, Advance Pharma, Alexion, Albireo, Bayer, Gilead, Eisai, Falk Foundation, Intercept, Ipsen, Janssen, MedUpdate GmbH, MSD/Merck, Novartis, Orphalan, Sequana Medica, SIRTEX, and SOBI; Nothing to disclose: AF, RG, UN, TB, MH, RG, CB, TTW, RB, HG, ND, MM, JUM, AK, KP, NKB.