Background and aim. The best strategy for managing patients with resolved hepatitis B virus infection (HBsAg negative, anti-HBc antibodies positive with or without anti-HBs antibodies) and hematological malignancies under immunosuppressive therapies has not been defined. The aim of this study was to prospectively analyze the risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation in these patients.

Material and methods. Twenty-three patients (20 positive for anti-HBs) were enrolled. Eleven patients underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (autologous in 7 cases, allogeneic in 4 cases) while the remaining 12 were treated with immunosuppressive regimens (including rituximab in 9 cases).

Results. During the study no patient presented acute hepatitis. However, three anti-HBc/anti-HBs positive patients who were treated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation demonstrated hepatitis B virus reactivation within 12 months from transplant. No one of the remaining patients showed hepatitis B virus reverse seroconversion.

Conclusions. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is a high risk condition for late hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with resolved infection. Reverse seroconversion seems to be a rare event in anti-HBc/anti-HBs positive patients submitted to autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or systemic chemotherapy with or without rituximab.

The reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV), which can result in liver injury of different severity, ranging from a subclinical asymptomatic course to severe, acute hepatitis and even death, is a very important issue in patients with hematological malignancies.1 Indeed, HBV related liver injury has been reported to be the third cause of liver disease after graft versus host disease and cytostatic drug hepatototoxicity in these patients.2 The impact of this problem is outstandingly relevant in Italy where, among patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, 8.5% have been reported to be positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and another 41.7% are positive for hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc).3 Because effective antiviral therapies are available for HBV, routine screening for the assessment of the individual HBV serological status is mandatory in each patient with oncohematological disease. Universal prophylaxis is well established as an effective treatment to prevent HBV hepatitis in HBsAg positive patients according to the present guidelines of the American and European Associations for the Study of Liver Disease,4,5 and has been shown to significantly reduce the rate of HBV related alanine-aminotransferase (ALT) flares, cessations of chemotherapy, liver failure, and deaths in these patients.6 However, the best strategy of managing HBsAg negative patients with resolved HBV infection who are anti-HBc positive with or without hepatitis B surface antibodies (anti-HBs) is less clear. It is well known that these patients may maintain low level of detectable HBV-DNA in the serum (usually < 200 IU/mL), liver or peripheral-blood mononuclear cells.7 The reappearance of HBsAg in the serum is usually associated with a decline of anti-HBs when present; this has been defined as reverse seroconversion and may be detected in these patients during and after profound immunosuppressive therapy.8 Reverse seroconversion may lead to HBV reactivation, defined by the presence of a significant HBV-DNA and ALT serum levels above the upper normal limit, and eventually to HBV hepatitis, defined as an increased serum ALT level exceeding three times the upper normal value or an increase of more than 100 U/L when compared to baseline pre-chemotherapy value associated with HBV reactivation in the absence of acute infection with hepatitis A or C viruses or other systemic infection.9,10 In patients with hematological malignancies this risk has been reported to be as high as 12% during conventional chemotherapy, but is most likely higher in patients treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), in whom it has been reported to range between 14 and 50%,11 or in patients treated with monoclonal antilymphocyte B and T antibodies (anti-CD20 and anti-CD52).7,9

In this study we prospectively analysed the risk of HBV reactivation in 23 patients who were HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive with or without anti-HBs and with hematological malignancies who underwent profound immunosuppressive therapy without any prophylactic antiviral treatment. Therefore, the primary objective of our study was the early detection of reverse seroconversion and/or of positive serum HBV-DNA in patients carrying antibodies to HBV to prevent acute HBV hepatitis; the secondary objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of therapy with nucleoside/nucleotide analogues in the prevention of hepatitis flare.

Material and MethodsPatients were consecutively enrolled in this prospective study during the period January-December 2008 in three Italian Hematology Departments (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome and Campobasso; Istituti Fisioterapici Ospedalieri, Rome). Informed consent was obtained from each patient and the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

All patients who were scheduled for treatment with anticancer therapy and/or HSCT for a lymphoproliferative or myeloproliferative disease were screened for the present study and had their serum HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc IgG determined. All HBsAg-negative patients found to be positive for anti-HBc were enrolled in the study, independently of the anti-HBs status. At the time of enrollment all patients were checked for co-infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and underwent serum assay of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), hepatitis B e antibody (anti-HBe), HBV-DNA and routine laboratory parameters assessing liver and kidney function. The serum HBV-DNA load was determined throughout the study by quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reactions (COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HBV test, Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland, threshold level 12 IU/mL). During the period of immunosuppressive therapy and for 18 months thereafter, the complete HBV serum markers, including anti-HBc IgM and HBV-DNA serum levels, were measured every three months. In the case of HBsAg reverse seroconversion (reappearance of serum HBsAg) with detectable HBV-DNA level, we started antiviral therapy with nucleoside/nucleotide analogues.

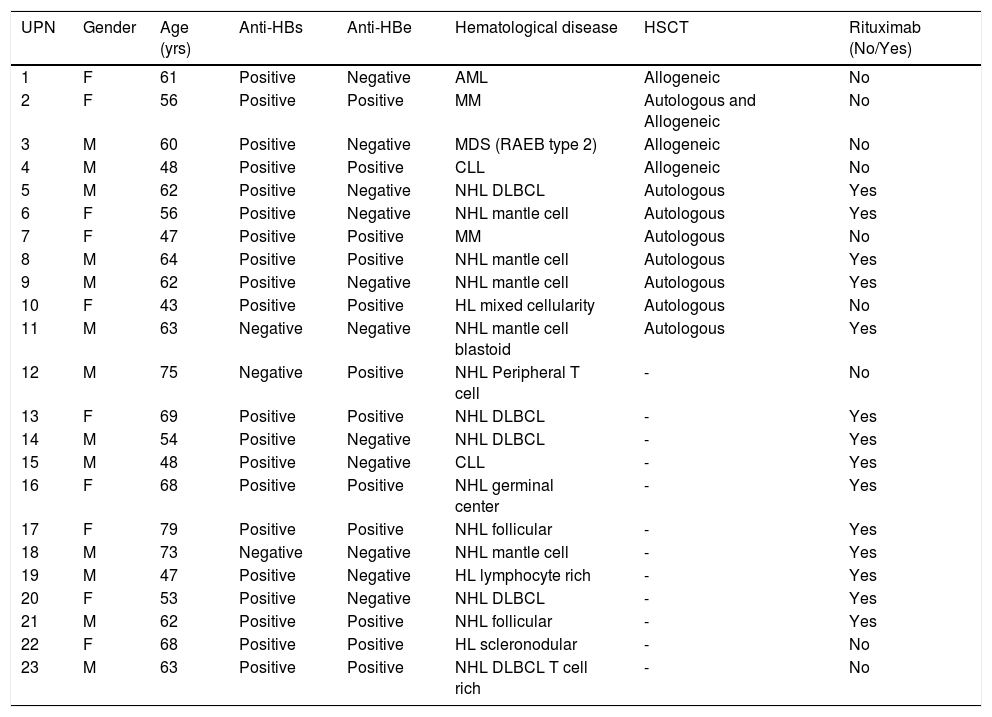

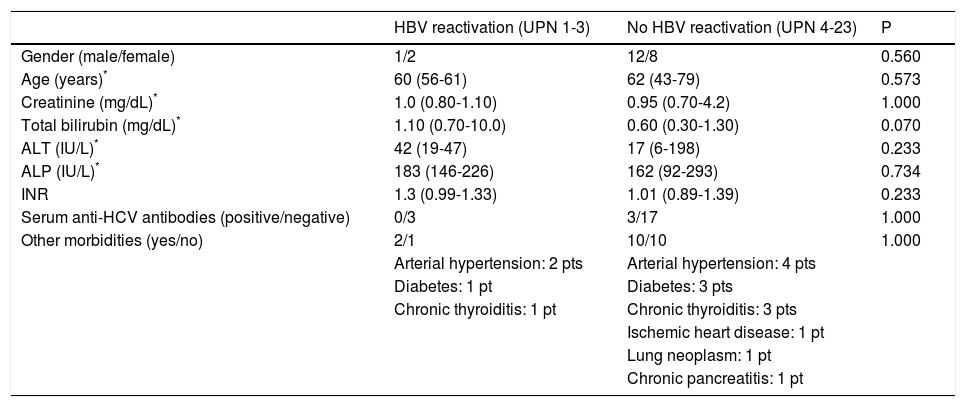

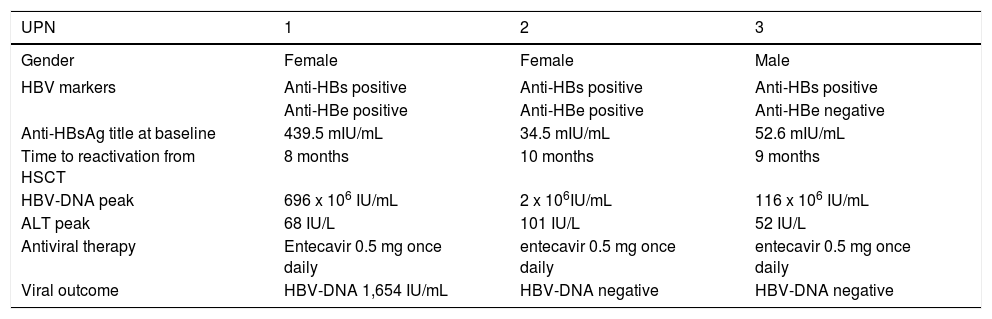

ResultsDuring the enrollment period, 266 patients with a new diagnosis of oncohematological malignancy scheduled for treatment were screened in our Departments. Of them, 4 patients (1.5%) resulted to be HB-sAg positive (1 HbeAg positive/anti-HBe negative and 3 HBeAg negative/anti-Hbe positive) and were immediately treated with nucleotide/nucleoside analogues before immunosuppression. Furthermore, we observed 28 anti-HBc positive/HBsAg negative patients (10.5%) who were enrolled in the study. Two patients dropped out because they preferred to refer to another Hematology Department, while 3 patients died after the enrollment due to hematological disease progression and could not complete the study. Among the 23 evaluable patients, there were 13 men and 10 women with a median age of 60 years (range 43-79 years) (Table 1). Twenty patients (87%) were positive for anti-HBs, (11 anti-HBe positive, 9 anti-HBe negative), and 3 (13%) were anti-HBs negative (1 anti-HBe positive, and 2 anti-HBe negative). All of the patients had undetectable HBV-DNA serum levels, and none of them tested positive for an antibody to HIV. All but 3 of the patients had negative serum assays for anti-HCV antibodies, and two of them were also HCV-RNA positive. The patients had various hematological malignancies, with lymphoma being the most frequent disease; three patients had Hodgkin lymphoma, and 14 patients had non-Hodgkin lymphoma (5 mantle cell, 5 diffuse large B cell, 3 follicular, 1 peripheral T-cell). The other patients had multiple myeloma (n = 2), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n = 2), acute myeloid leukemia (n = 1) or myelodysplastic syndrome (refractory anemia with excess of blasts type 2, n = 1). They underwent various treatment regimens according to the different hematological disease, In particular, among the 12 patients submitted to immune suppression without HSCT, the treatment regimen included rituximab in 9 patients. Furthermore, when considering the 11 patients treated with HSCT, 7 received autologous transplant, and 3 received allogeneic transplant, while the remaining patient underwent both autologous and allogeneic transplants (Table 1). Indeed, all but one HSCT patients had detectable antibodies to HBsAg, with serum levels ranging from 34 to 1,000 lU/mL (mean 230.5 lU/mL), and all of the stem cell donors for patients treated with HSCT tested negative for HBV serum markers. Follow-up for the post-immunosuppression period was calculated from the date of last administration of chemotherapy or date of HSCT. The median follow-up period was 35 months (range 18-45 months). During the course of the study, no patient experienced HBV hepatitis. However, 3 of the 23 patients enrolled in the study (13%, patients 1-3 in table 1) experienced HBV reactivation. No significant differences regarding demographical parameters, kidney and liver function tests, serum anti-HCV positivity, and presence of other morbidities were found between patients with and without HBV reactivation at enrollment (Table 2). The patients with HBV reactivation showed reappearance of HBsAg and HBeAg in the serum, negative anti-HBe and anti-HBs, detectable HBV-DNA, and a mild increase of serum ALT level, and were affected by acute myeloid leukemia, multiple myeloma and myelodysplastic syndrome, respectively (Table 3). They tested positive for anti-HBs prior to the start of haematological therapy, and patients 1 and 2 were also anti-HBe positive; in particular, patient 1 had a high titer of anti-HBsAg (439.5 mUI/mL), while patients 2 and 3 had an intermediate titer (34.5 and 52.6 mUI/mL). At the time of HSCT, the anti-HBs titer was significantly reduced in patient 1 (17.9 mUI/mL), undetectable in patient 2, and slightly decreased in patient 3. All of these patients had undergone allogeneic HSCT (patient 2 was previously treated with unsuccessful autologous HSCT), and virus reactivation was detected 8, 10 and 9 months after HSCT, respectively.

Clinical features of the enrolled patients.

| UPN | Gender | Age (yrs) | Anti-HBs | Anti-HBe | Hematological disease | HSCT | Rituximab (No/Yes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 61 | Positive | Negative | AML | Allogeneic | No |

| 2 | F | 56 | Positive | Positive | MM | Autologous and Allogeneic | No |

| 3 | M | 60 | Positive | Negative | MDS (RAEB type 2) | Allogeneic | No |

| 4 | M | 48 | Positive | Positive | CLL | Allogeneic | No |

| 5 | M | 62 | Positive | Negative | NHL DLBCL | Autologous | Yes |

| 6 | F | 56 | Positive | Negative | NHL mantle cell | Autologous | Yes |

| 7 | F | 47 | Positive | Positive | MM | Autologous | No |

| 8 | M | 64 | Positive | Positive | NHL mantle cell | Autologous | Yes |

| 9 | M | 62 | Positive | Negative | NHL mantle cell | Autologous | Yes |

| 10 | F | 43 | Positive | Positive | HL mixed cellularity | Autologous | No |

| 11 | M | 63 | Negative | Negative | NHL mantle cell blastoid | Autologous | Yes |

| 12 | M | 75 | Negative | Positive | NHL Peripheral T cell | - | No |

| 13 | F | 69 | Positive | Positive | NHL DLBCL | - | Yes |

| 14 | M | 54 | Positive | Negative | NHL DLBCL | - | Yes |

| 15 | M | 48 | Positive | Negative | CLL | - | Yes |

| 16 | F | 68 | Positive | Positive | NHL germinal center | - | Yes |

| 17 | F | 79 | Positive | Positive | NHL follicular | - | Yes |

| 18 | M | 73 | Negative | Negative | NHL mantle cell | - | Yes |

| 19 | M | 47 | Positive | Negative | HL lymphocyte rich | - | Yes |

| 20 | F | 53 | Positive | Negative | NHL DLBCL | - | Yes |

| 21 | M | 62 | Positive | Positive | NHL follicular | - | Yes |

| 22 | F | 68 | Positive | Positive | HL scleronodular | - | No |

| 23 | M | 63 | Positive | Positive | NHL DLBCL T cell rich | - | No |

UPN: unique patient number. anti-HBs: hepatitis B surface antibodies. anti-HBe: hepatitis B e antigen antibodies. HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. AML: acute myeloid leukemia. MM: multiple myeloma. MDS (RAEB type 2): myelodysplastic syndrome (refractory anemia with excess of blasts type 2). CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia. NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma. DLBCL diffuse large B cell lymphoma. HL: Hodgkin lymphoma.

Baseline features of patients with and without HBV reactivation.

| HBV reactivation (UPN 1-3) | No HBV reactivation (UPN 4-23) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 1/2 | 12/8 | 0.560 |

| Age (years)* | 60 (56-61) | 62 (43-79) | 0.573 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL)* | 1.0 (0.80-1.10) | 0.95 (0.70-4.2) | 1.000 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL)* | 1.10 (0.70-10.0) | 0.60 (0.30-1.30) | 0.070 |

| ALT (IU/L)* | 42 (19-47) | 17 (6-198) | 0.233 |

| ALP (IU/L)* | 183 (146-226) | 162 (92-293) | 0.734 |

| INR | 1.3 (0.99-1.33) | 1.01 (0.89-1.39) | 0.233 |

| Serum anti-HCV antibodies (positive/negative) | 0/3 | 3/17 | 1.000 |

| Other morbidities (yes/no) | 2/1 | 10/10 | 1.000 |

| Arterial hypertension: 2 pts | Arterial hypertension: 4 pts | ||

| Diabetes: 1 pt | Diabetes: 3 pts | ||

| Chronic thyroiditis: 1 pt | Chronic thyroiditis: 3 pts | ||

| Ischemic heart disease: 1 pt | |||

| Lung neoplasm: 1 pt | |||

| Chronic pancreatitis: 1 pt |

Data are provided as median and range. Continuous variables were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test for unpaired data. Categorical variables were analyzed with Fisher’s exact test. HBV: hepatitis B virus. UPN: unique patient. ALT: alanine-aminotransferase. ALP: alkaline phosphatase. INR: international normalized ratio. HCV: hepatitis C virus.

Characteristics of patients with HBV reactivation.

| UPN | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | Female | Male |

| HBV markers | Anti-HBs positive | Anti-HBs positive | Anti-HBs positive |

| Anti-HBe positive | Anti-HBe positive | Anti-HBe negative | |

| Anti-HBsAg title at baseline | 439.5 mIU/mL | 34.5 mIU/mL | 52.6 mIU/mL |

| Time to reactivation from HSCT | 8 months | 10 months | 9 months |

| HBV-DNA peak | 696 x 106 IU/mL | 2 x 106IU/mL | 116 x 106 IU/mL |

| ALT peak | 68 IU/L | 101 IU/L | 52 IU/L |

| Antiviral therapy | Entecavir 0.5 mg once daily | entecavir 0.5 mg once daily | entecavir 0.5 mg once daily |

| Viral outcome | HBV-DNA 1,654 IU/mL | HBV-DNA negative | HBV-DNA negative |

UPN: unique patient number. HBV: hepatitis B virus. HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Anti-HBs: antibodies to hepatitis B s antigen. Anti-HBe: antibodies to hepatitis B e antigen. ALT: alanine-aminotransferase.

After the detection of HBV reactivation, all three patients were effectively treated with entecavir 0.5 mg once daily, which resulted in the progressive decrease of the serum HBV-DNA and ALT levels. Patient 1 died 30 months after the allogeneic HSCT due to recurrence of acute myeloid leukemia; at that time she still showed low serum levels of HBV-DNA. Six months after initiating entecavir therapy, patient 2 showed loss of HBsAg, undetectable HBV-DNA, and reappearance of anti-HBs; these viral findings were still present on March 2012, 43 months after the allogeneic HSCT, when the patient died due to respiratory failure complicating graft vs. host disease. Finally, patient 3 died 33 months after the allogeneic HSCT due to recurrent mielodysplastic syndrome; at that time, the patient showed an undetectable serum level of HBV-DNA and normal serum ALT.

Among the anti-HBs patients without HBV reactivation, one patient showed a transient loss of anti-HBs whereas the HBV-DNA remained negative, and another one showed anti-HBe loss while maintaining detectable anti-HBs. With respect to the 3 anti-HBs negative patients, one patient underwent autologous HSCT, and two received an immunosuppressive regimen, including rituximab in one case; no change in the HBV serological status was detected in any of these patients.

DiscussionThe therapeutic approach to HBsAg negative/ anti-HBc positive patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy is controversial: Lok, et al. did not recommend routine antiviral prophylaxis with nucleoside or nucleotide analogues for such individuals.4 However, according to the guidelines of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, HBsAg-negative patients with positive anti-HBc antibodies and undetectable HBV-DNA in the serum who received chemotherapy and/or immunosuppression should be followed carefully through ALT and HBV-DNA testing performed at 1- to 3-month intervals and treated with antiviral therapy upon confirmation of HBV reactivation before ALT elevation.5 Conversely, universal antiviral prophylaxis has been proposed for all anti-HBc positive patients undergoing therapy for hematological malignancies,12 exclusively in patients with detectable HBV-DNA,5,11 or in patients who need to be treated with intense immunosuppressive regimens, such as chemotherapy with fludarabine, dose-dense regimens, HSCT, autologous myeloablative transplant, induction in acute leukaemia or the use of monoclonal antibodies.9

Oncohematological pts with resolved HBV infection exposed to intensive immunosuppression without prophylaxis have a reactivation risk ranging from 3 to 25% according to available data,2,13 and reactivation from resolved HBV infection under immunosuppressive conditions has been recently characterized by low genetic heterogeneity with the wild type G1896 or G1896A variant prevalent using ultra-deep sequencing analysis of the entire HBV genome in serum.14

In HSCT patients the HBV reverse seroconversion usually occurs as a delayed event and may have relevant clinical consequences since reconstitution of immunity after tapering or withdrawal of cytotoxic therapies may trigger immune-mediated injury of infected hepatocytes that results in acute hepatitis with a clinical picture ranging from subclinical transaminase elevation, to jaundice or fulminant liver failure and death.15

The overall percentage of HBV reactivation in our study group of anti-HBc positive patients was 13%, but if we only consider patients submitted to HSCT this rate increased to 27.3%, similar to that found in a recent prospective study showing that HBV reactivation occurred in 5/19 patients (26%) with resolved HBV hepatitis treated with HSCT.16 Notably, the risk of HBV reactivation appeared to be substantially higher in patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT (3/4, 75%) compared with patients treated with autologous HSCT (0/7). The rate of HBV reactivation in allogenic HSCT in our study was higher than that reported in recent retrospective series, where the rate ranged from 12 to 21.4% and the risk factors for HBV reactivation were reported to be chronic oncohematological disease, duration of chemotherapy regimens before HSCT and younger age at transplantation.15,17,18 Our results should be interpreted with caution considering the limited number of patients evaluated; however, considering the prospective design of the study, a remarkable accuracy in the diagnosis of reactivation was possible. Indeed, the periodic evaluation at 3-month intervals allowed us to detect HBV reactivation before the occurrence of clinically overt acute HBV hepatitis, which is considered an index event of HBV reactivation in retrospective studies. Interestingly, the presence of anti-HBs did not decrease the risk of HBV reactivation in the setting of allogeneic HSCT because all of our patients had initially detectable antibodies to HBsAg. Conversely, none of the patients undergoing autologous HSCT developed reverse seroconversion, thus confirming that this therapeutic approach entails a lower risk of reactivation, at least in patients with anti-HBs positivity. Accordingly, in their retrospective series, Ceneli, et al. reported that only 2/39 (5%) anti-HBc positive patients submitted to autologous HSCT developed HBV reactivation. Eleven of the patients included in that study had multiple myeloma, and this disease was an independent risk factor for HBV reactivation based on multivariate analysis.19

None of our 12 patients who received immunosuppressive treatments without HSCT presented with reverse seroconversion throughout the evaluation period, though 9 of them were treated with therapeutic regimens including rituximab. In the prospective study published by Fukushima, et al, 24 anti-HBc patients with malignant lymphoma were enrolled during the period 2005-2008. Twenty-one of their patients with B-cell lymphoma were treated with a regimen including rituximab, but HBV reactivation was observed in only one patient (4.1%).20 The absence of HBV reactivation in our patients may be related to the high rate of anti-HBs positivity (10/12, 83.3%). Indeed, the partial protective role against HBV reactivation of anti-HBs in this setting of patients has been demonstrated in large retrospective series. Yeo, et al. reported a series of HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma treated with either cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) alone or rituximab plus CHOP. Acute hepatitis associated with HBV reactivation was observed only in the rituximab plus CHOP group (25% of the cases); in males, the absence of anti-HBs and the use of rituximab were demonstrated to be predictive of HBV reactivation.10 More recently, in a series of 62 HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive patients with lymphoma who were treated with rituximab, Koo, et al. found that the overall HBV reactivation hepatitis rate was only 3% and the possible risk factors included advanced age, undetectable anti-HBs and advanced lymphoma at the time of diagnosis. None of the patients who tested positive for anti-HBs experienced HBV reactivation.21 In 29 patients with B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab containing regimens, Pei, et al. showed that anti-HBs was lost in 8/29 cases (27.6%). Interestingly, none of the 10 cases with anti-HBs titers higher than 100 mIU/mL before start of rituximab became negative for anti-HBs; furthermore among the patients with anti-HBs loss, only one experienced HBsAg reappearance in the serum.22 The possible protective role of high anti-HBs titers seems to be confirmed in a recent series showing that HBV reactivation occurred in 3/30 patients (10%) with resolved HBV infection and hematologic malignancy receiving rituximab based therapy. In this study no patients with anti-HBs titers exceeding 200 mIU/mL at baseline showed HBV reactivation.16

ConclusionIn conclusion our study shows that allogeneic HSCT is a high risk factor for late HBV reactivation in patients with resolved HBV infection. We did not observe HBV reactivation in patients treated with autologous HSCT or systemic chemotherapy including rituximab. Accordingly, we think that in these patients, closely monitoring the anti-HBs and HB-sAg at 1 month intervals could be sufficient to prevent overt hepatitis, at least in subjects who are anti-HBs positive without detectable serum HBV-DNA at baseline. Larger prospective studies are needed to compare risks and benefits of an observational/early intervention approach versus general prophylaxis. In patients undergoing periodic viro-logical assessment, we propose to immediately start prophylactic treatment with analogues when anti-HBs disappears and/or HBsAg appears, regardless of the serum level of HBV-DNA.

Abbreviations- •

ALT: alanine-aminotransferase.

- •

anti-HBc: hepatitis B core antibody.

- •

anti-HBe: hepatitis B e antibody.

- •

anti-HBs: hepatitis B surface antibody.

- •

CHOP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicine, vincristine, prednisone.

- •

HBeAg: hepatitis B e antigen.

- •

HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen.

- •

HBV: hepatitis B virus.

- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

- •

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

- •

HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

- •

Guarantor of the article: Maurizio Pompili M.D.

- •

Authors’ contribution: MP, MB and SH designed the study and drafted the manuscript; GB performed the statistical analysis; LN, MDA, SF, AG, LL, CM, LP, GLR, ST collected the data, participated in the study design and helped draft the manuscript; SS and RL made critical revisions of the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

- •

Potential competing interests: none.

This work was funded by Associazione Italiana Studio Fegato (AISF) with a grant to Maria Basso entitled to Prof. Mario Coppo.