Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most frequent primary form of liver cancer, is a significant global health challenge due to its high morbidity and mortality. It is the sixth most common cancer worldwide by incidence and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths [1]. Annually, over 800,000 new cases of HCC are diagnosed, and approximately 700,000 deaths are attributed to the disease. Its prevalence varies geographically, with the highest incidence rates observed in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa [2]. In France, cirrhosis and liver cancer account for 15,000 and 10,000 deaths per year, respectively [3,4]. The number of new HCC cases has risen significantly over the decades with around 11,000 new cases in 2023, and HCC became the leading cause of registration on the liver transplant list [5].

Despite advances in medical care, the overall survival (OS) of patients with HCC is relatively poor. The 5-year survival rate varies between 5 % and 30 % worldwide; in France it is 18 % [4]. This is mainly due to late diagnosis, which explains why only 25 % of patients are eligible for curative treatment at diagnosis such as resection, ablation or transplantation, worldwide [6]. In France, the rate of patients accessing curative treatment progressively increased, from 23 and 25 % [7,8] between 2009 and 2012, to 30 % in 2015–2017 and 40 % in 2019–2021 [9,10].

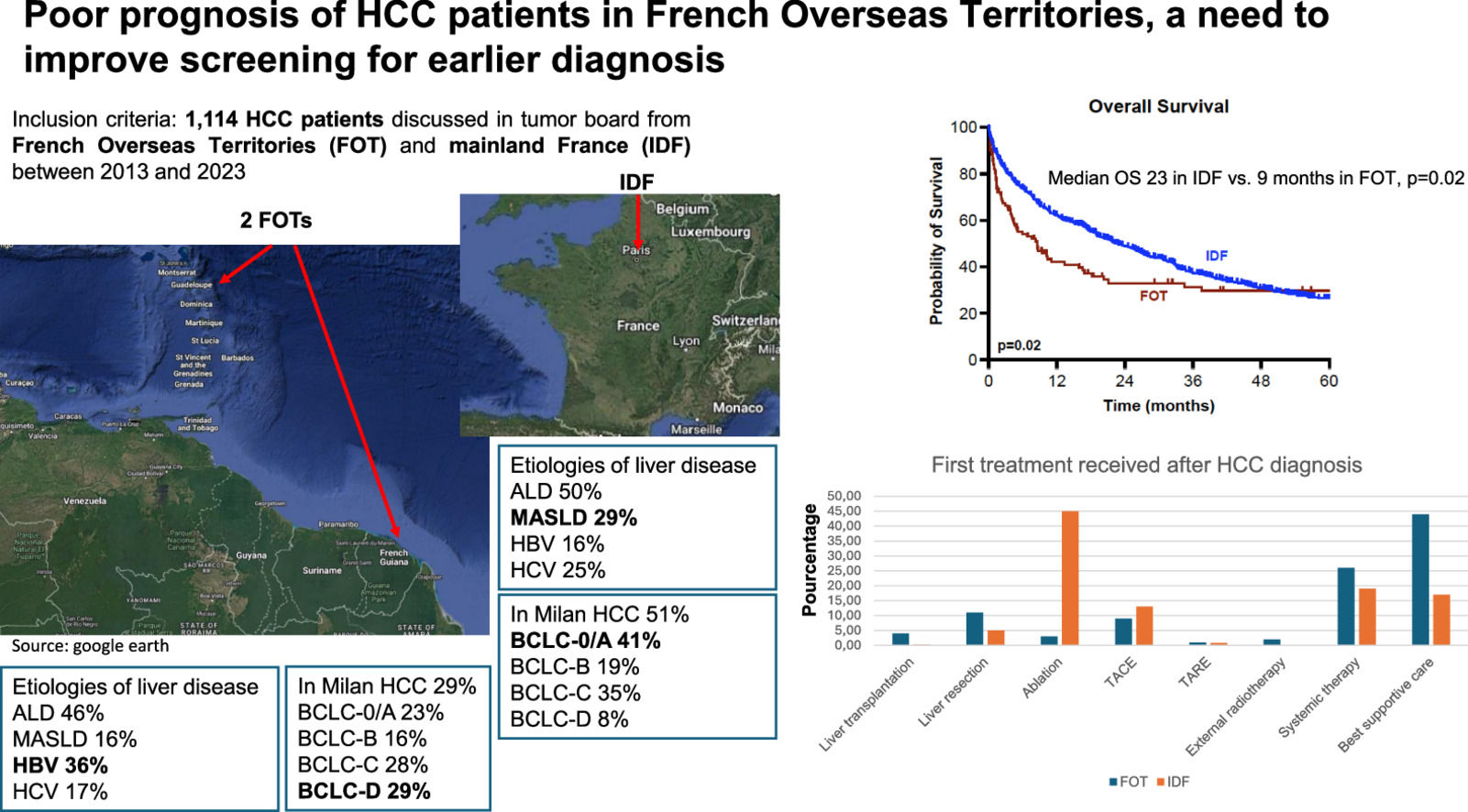

The French overseas territories (FOT) have administrative statuses that are similar to mainland France; they share the same universal health system and health insurance. However, they are very different in terms of epidemiology and have specific cultural contexts that may be relevant to HCC. Indeed, the prevalence of hepatitis B, the attitudes towards vaccination, the alcohol consumption, the prevalence of obesity and diabetes are different from mainland France. Furthermore, poverty is more frequent and hampers access to care in a context of low specialized health professional density, notably in French Guiana. All the above raise the question that the epidemiology and prognosis of HCC in the FOT may be quite different from mainland France [11–18]. Yet epidemiological data on HCC in the FOT remains limited [19].

This retrospective study thus aimed to compare OS between HCC patients from two FOT (French Guiana and Guadeloupe) and a tertiary French metropolitan center located in Île-de- France (IDF), focusing on HCC characteristics, staging at diagnosis, treatment approaches by Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC stage), and OS across different BCLC stages in these regions.

2Patients and Methods2.1Study populationThis retrospective study included all patients with a diagnosis of HCC discussed in multidisciplinary tumor board meetings at three care centers: Avicenne in mainland France (IDF), Guadeloupe and French Guiana between 2013 and 2023. FOT referred to the combination of Guadeloupe and French Guiana.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of Guadeloupe (A147_12/11/2024), and data were collected with the consent of patients who were informed individually orally. For patients in mainland France (IDF), clinical data were collected with the consent of patients who were informed individually both orally and by an information notice within the framework of the authorization to establish the AP-HP Data Warehouse filed in July 2016 with the National Commission for Information Technology and Civil Liberties (no. 1980120).

Eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) newly diagnosed HCC, confirmed either histologically or through non-invasive imaging criteria using contrast-enhanced CT or MRI, according to EASL guidelines [20]; (2) cases discussed in the multidisciplinary tumor board meetings of Guadeloupe, French Guiana, and IDF between 2013 and 2023.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) absence of follow-up data, (2) unavailable BCLC classification; (3) previous diagnosis of HCC.

2.2Study protocol and endpointsDemographic data, medical history, current treatments, cirrhosis etiology, liver function (Child-Pugh score, MELD score), and tumor characteristics (number/size of lesions, vascular invasion, extrahepatic spread, and AFP levels) were collected at the time of initial HCC diagnosis. Patients were classified according to BCLC stage, Milan criteria and AFP score as already described. The presence of clinically significant portal hypertension was defined by the presence of esophageal varices (EV) detected on upper endoscopy. Varices were classified into four grades: no varices, grade 1 (small, straight varices), grade 2 (moderately enlarged, beady varices), and grade 3 (large, nodular, or tumor-like varices). Grades 2 and 3 were considered large varices. The selection of HCC treatment during multidisciplinary tumor board meetings was guided by the available treatment options and the expertise of each center. The diagnosis of HCC was made on liver biopsy, or on typical cross-sectional imaging (CT or MRI). The diagnosis of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) was made in the presence of compatible histology or, in the absence of histology, in the presence of a metabolic context (type 2 diabetes, obesity, arterial hypertension and/or dyslipidemia). For the purpose of this study, the first treatment performed after the multidisciplinary tumor board meeting was recorded. Curative treatment was defined as the initial treatment consisting of either ablation, liver resection, or liver transplantation. Patients who benefited from liver transplantation during follow-up were recorded. Follow-up ended in December 2024.

The primary endpoint of the study was to compare the overall survival—defined as the time from HCC diagnosis to death from any cause—between FOT and IDF.

The secondary endpoints were to (i) describe the characteristics of the populations of FOT and IDF, with a particular focus on HCC features and staging at diagnosis, (ii) compare the treatments proposed by each center according to BCLC stage, and (iii) compare the overall survival across different BCLC stages between the centers.

2.3Statistical analysisPatient characteristics were summarized as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables, and as counts (percentages) for categorical variables. To compare continuous and categorical data between groups, the Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test were employed, respectively. Event times were calculated from the diagnosis of HCC, with event incidence estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Group comparisons were made using the log-rank test. Associations between variables and clinical events were evaluated using univariate Cox proportional hazards models. Variables with a P-value <0.05 were included in a multivariate Cox regression model, with a backward stepwise elimination method employed to identify independent predictors. The hazard ratios (HR) and corresponding 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each factor. The proportional hazards assumption was verified graphically and using the Schoenfeld and scaled Schoenfeld residuals method.

3Results3.1Baseline characteristics of the patientsBetween 2013 and 2023, 1114 patients with a new diagnosis of HCC met the inclusion criteria (FOT 11 %, n=116; IDF 89 %, n=998). Among these patients, 7 % were diagnosed through a surveillance programs, 46 % due to the presence of symptoms, and 47 % were identified on imaging in the absence of symptoms—such as in the context of abnormal liver function tests. Patients in FOT had a higher prevalence of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) (36 %) compared to IDF (16 %) (p<0.001). MASLD was primarily more frequent in IDF (29 %) compared to FOT (16 %) (p=0.004). There was no significant difference in the etiology of alcohol (p=0.40). The MELD score at diagnosis was higher in FOT, with a median of 12 (10–19), compared to 9 (8–11) in IDF (p<0.001) (Table 1), and only 43 % of patients in FOT were classified as Child-Pugh A, compared to 70 % in IDF (p<0.001).

Baseline characteristics at first diagnosis of HCC.

*Number (percentage); °median [range]; $Pearson’s Chi-squared test; Fisher’s exact test; Wilcoxon rank sum test, comparison between FOT and IDF.

ALD: alcoholic liver related disease; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; EV: esophageal varices; FOT: French overseas territories; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; IDF: Ile de France; MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic Liver disease; MELD score: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

HCC patients in FOT were diagnosed in 71 % of cases outside Milan criteria, compared to 49 % in IDF (p<0.001). Additionally, 29 % of patients in FOT were classified as BCLC-D at diagnosis, compared to 5 % in IDF (p<0.001) (Table 1). Only 22 % of patients in FOT were able to receive curative treatment compared to 51 % in IDF (p<0.001), and 44 % of patients received best supportive care as first treatment in FOT compared to 17 % in IDF (p<0.001) (Table 2).

First HCC treatments received after HCC diagnosis.

| Baseline characteristics | Whole cohortN=1114 | IDFN=998 | FOTN=116 | P$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cohort | ||||

| Liver transplantation* | 8 (0.8) | 2 (0.2) | 6 (4) | <0.001 |

| Liver resection* | 62 (6) | 49 (5) | 13 (11) | |

| Ablation* | 454 (41) | 451 (45) | 3 (3) | |

| TACE* | 143 (13) | 133 (13) | 10 (9) | |

| TARE* | 13 (1) | 12 (0.8) | 1 (1) | |

| External radiotherapy* | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | |

| Systemic therapy* | 216 (19) | 186 (19) | 30 (26) | |

| Best supportive care* | 216 (19) | 165 (17) | 51 (44) | |

| BCLC-0/A | ||||

| Liver transplantation* | 6 (1.5) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (13) | <0.001 |

| Liver resection* | 41 (9) | 28 (7) | 12 (39) | |

| Ablation* | 331 (75) | 328 (80) | 3 (10) | |

| TACE* | 30 (7) | 26 (6) | 4 (13) | |

| TARE* | 6 (1.5) | 5 (1.5) | 1 (3) | |

| External radiotherapy* | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Systemic therapy* | 4 (0.9) | 4 (1) | 1 (3) | |

| Best supportive care* | 20 (5) | 17 (4) | 5 (16) | |

| BCLC-B | ||||

| Liver transplantation* | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | <0.001 |

| Liver resection* | 16 (8) | 16 (9) | 0 (0) | |

| Ablation* | 52 (26) | 52 (28) | 0 (0) | |

| TACE* | 73 (36) | 71 (38) | 2 (11) | |

| TARE* | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | |

| External radiotherapy* | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Systemic therapy* | 33 (16) | 21 (11) | 12 (63) | |

| Best supportive care* | 27 (13) | 24 (13) | 3 (11) | |

| BCLC-C | ||||

| Liver transplantation* | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | <0.001 |

| Liver resection*° | 6 (2) | 5 (1.4) | 1 (3) | |

| Ablation*°° | 71 (18) | 71 (20) | 0 (0) | |

| TACE* | 40 (10) | 36 (10) | 4 (12) | |

| TARE* | 6 (1.6) | 6 (1.6) | 0 (0) | |

| External radiotherapy* | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Systemic therapy* | 178 (46) | 161 (46) | 17 (52) | |

| Best supportive care* | 81 (21) | 72 (21) | 9 (27) | |

BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; FOT: French overseas territories; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; IDF: Ile de France; TACE: trans arterial chemoembolization; TARE: trans arterial radioembolization.

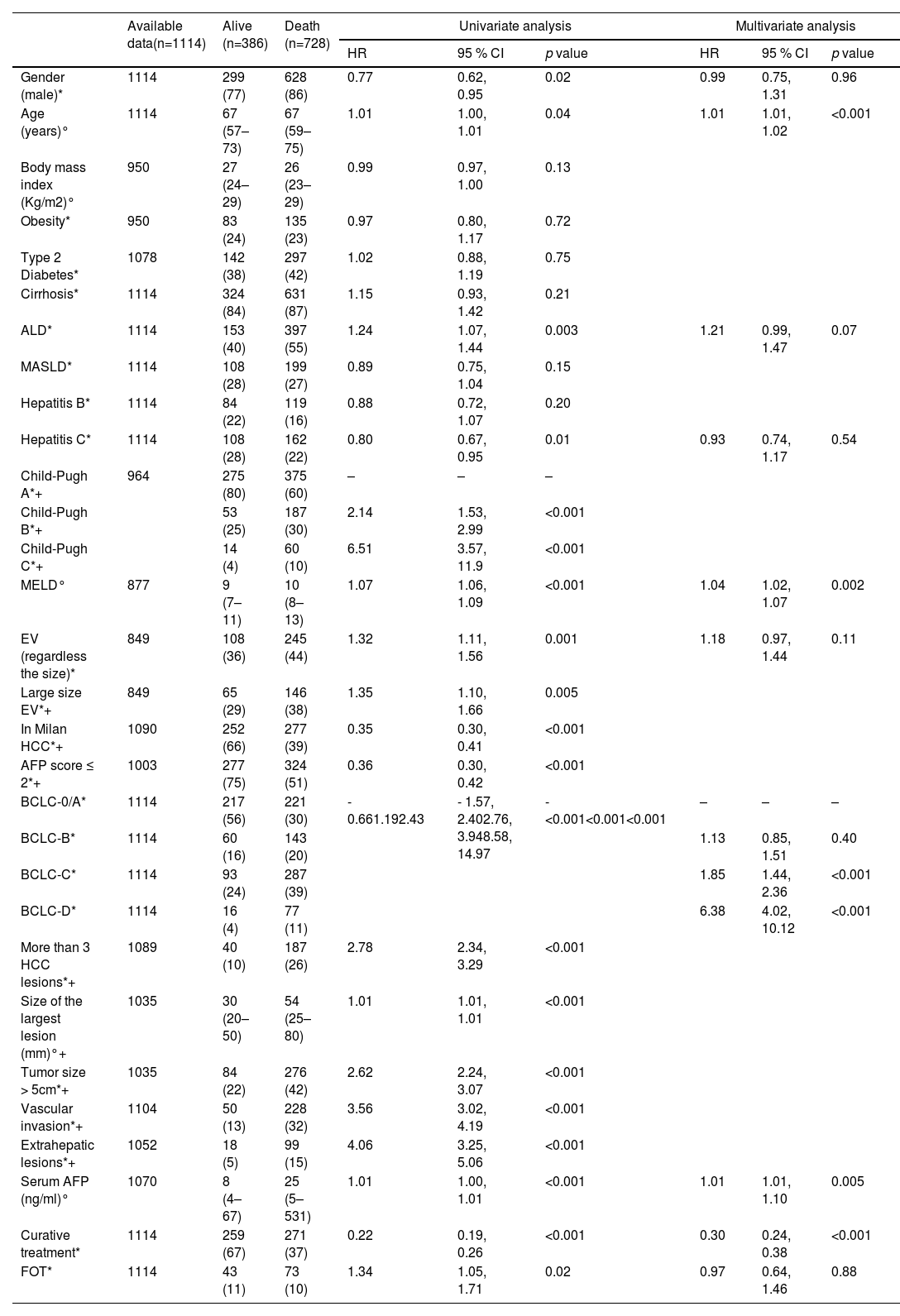

Median OS in the whole cohort was 21.2 months, with 60 %, 37 % and 27 % at 12, 36 and 60 months. Median OS was significantly higher in IDF compared to FOT (23 vs. 9 months, p=0.02) (Fig. 1A). In multivariate analysis, MELD score (HR=1.04, 95 % CI [1.02–1.07]), BCLC-C stage (HR=1.85, 95 % CI [1.44–2.36]), BCLC-D stage (HR=6.38, 95 % CI [4.02–10.12]), and AFP serum level (HR=1.01, 95 % CI [1.01–1.10]) were associated with higher mortality, while access to curative treatment (HR=0.30, 95 % CI [0.24–0.38]) was linked to OS in the whole cohort (Table 3).

Overall survival in patients with a first diagnosis of HCC.

A. OS according to FOT and IDF in the whole cohort.

B. OS according to FOT and IDF in BCLC 0/A patients.

C. OS according to FOT and IDF in BCLC B patients.

D. OS according to FOT and IDF in BCLC C patients.

E. OS according to FOT and IDF in BCLC D patients.

F. OS according to GUA, GUY and IDF.

BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; FOT: French overseas territories; GUA: Guadeloupe; GUY: French Guiana; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; IDF: Île de France.

Results represented using the Kaplan-Meier Method with the log-rank test. The numbers of patients at risk are figured under the x-axis.

Baseline predictive factors of mortality for the whole cohort (Cox proportional hazard regression models).

*Number (percentage); °median [range].

ALD: alcoholic liver related disease; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; EV: esophageal varices; FOTI: French overseas territories; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic Liver disease; MELD score: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

+ In Milan HCC, AFP score ≤ 2, More than 3 HCC lesions, Size of the largest lesion (mm), Tumor size > 5 cm, Vascular invasion, extrahepatic lesions were not entered in the multivariate analysis in order to avoid collinearity with BCLC classification, as well as Child-Pugh score to avoid collinearity with MELD, and as well as large size EV to avoid collinearity with EV (regardless the size.

There was no significant difference in overall survival between the 2 regions according to whether or not curative treatment was performed (Fig. 2A, 2B). In IDF, older age (HR=1.02, 95 % CI [1.01–1.02], p<0.001), MELD score (HR=1.04, 95 % CI [1.02- 1.07], p=0.005), BCLC-C (HR=1.80, 95 % CI [1.41–2.31], p<0.001) and BCLC-D (HR=5.72, 95 % CI [3.40–9.06], p<0.001) were independently associated with higher mortality, while access to curative treatment (HR=0.30, 95 % CI [0.23–0.37], p<0.001) was associated with lower mortality (Supplementary Table 1). In FOT, BCLC-D (HR=6.20, 95 % CI [1.98–19.40], p=0.002) was associated with higher mortality while access to curative treatment (HR=0.24, 95 % CI [0.08–0.71], p=0.009) was an independent prognostic factor (Supplementary Table 2).

Overall survival in patients with a first diagnosis of HCC.

A. OS according to FOT and IDF in curative treatment.

B. OS according to FOT and IDF in no curative treatment.

BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; FOT: French overseas territories; GUA: Guadeloupe; GUY: French Guiana; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; IDF: Île de France.

Results represented using the Kaplan-Meier Method with the log-rank test. The numbers of patients at risk are figured under the x-axis.

Finally, during a median follow-up of 15.2 months (4–104) of the whole cohort, 43 patients received liver transplantation (4 %) including 36 patients in IDF (4 %) and 7 patients in FOT (6 %). Among them, 24 patients were classified BCLC-0/A, 9 BCLC-B, 8 BCLC-C and 2 BCLC-D respectively. Of these 43 patients, 8 received a liver transplant as their first treatment after diagnosis.

3.3Similar outcomes in BCLC-0/A across the centersAmong 441 BCLC-0/A patients, MASLD was the most frequent etiology of underlying chronic liver disease in IDF (35 % vs. 7 %, p=0.001) while it was HBV infection in FOT (42 % vs. 15 %, p<0.001). Liver function, portal hypertension surrogate markers and HCC characteristics were not statistically different across IDF and FOT (Supplementary Table 3). In 92 % of cases, HCC were classified in Milan criteria in IDF compared to 73 % in FOT (p=0.004). Surgery was performed more frequently in FOT (39 %) compared to IDF (7 %, p<0.001), especially liver transplantation in first line (13 % vs. 0.5 %, p=0.001), IDF where 80 % of the patients were treated by ablation (Table 2). The median survival for BCLC-0/A patients was not statistically different across regions (45 months in IDF vs. 77 in FOT, p=0.18) (Fig. 1B). In multivariate analysis, older age (HR=1.03, 95 % CI [1.01–1.05], p=0.004), higher BMI (HR=1.05, 95 % CI [1.01- 1.09], p=0.02) and higher MELD score (HR=1.10, 95 % CI [1.05–1.15], p<0.001) were independently associated with mortality, while the access to curative treatment was associated with increased survival (HR=0.47, 95 % CI [0.29–0.77], p=0.002) (Table 4).

Baseline predictive factors of mortality for BCLC-0/A patients (Cox proportional hazard regression models).

*Number (percentage); °median [range].

ALD: alcoholic liver related disease; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; EV: esophageal varices; FOT: French overseas territories; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic Liver disease; MELD score: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

+ Child-Pugh score was not entered in the multivariate analysis in order to avoid collinearity with MELD.

Except for a higher rate of HBV infection in FOT compared IDF (33 % vs. 14 %, p=0.04), as well as a higher AFP level (674 vs. 11 ng/ml, p=0.02) and a lower number of patients within AFP score ≤ 2 (21 % vs. 49 %, p=0.05), the characteristics of the population were comparable between the 2 groups, especially regarding liver function (Supplementary Table 4). In IDF, more BCLC-B patients had access to ablation and surgical treatment (37 % vs 1 %, p=0.007), whereas systemic therapy was more frequently prescribed in FOT for this population of patients (63 % vs. 11 %, p<0.001) (Table 2). Median OS was 19.2 months in IDF compared to 8.7 months in FOT (p=0.36) (Fig. 1C). AFP score ≤ 2 (HR=0.50, 95 % CI [0.35–0.72], p<0.001) and curative treatment (HR=0.48, 95 % CI [0.33–0.69], p<0.001) were independently associated with lower mortality (Table 5).

Baseline predictive factors of mortality for BCLC-B patients (Cox proportional hazard regression models).

*Number (percentage); °median [range].

ALD: alcoholic liver related disease; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; EV: esophageal varices; FOT: French overseas territoriesHCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic Liver disease; MELD score: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

+ In Milan HCC, Size of the largest lesion (mm), Tumor size > 5 cm were not entered in the multivariate analysis in order to avoid collinearity with AFP score ≤ 2.

Median OS was not statistically different between IDF and FOT (7.8 months vs. 8.52 months) (Fig. 1D). In FOT compared to IDF, patients presented with significant higher MELD (12 vs. 9, p=0.009), extrahepatic lesions (45 % vs. 25 %, p=0.01) and HBV infection (45 % vs. 21 %, p=0.001) (Supplementary Table 5). Curative treatment proportion was not statistically different across regions (6 % (3 % liver transplantation, 3 % liver resection) in FOT vs. 21.4 % (20 % ablation, 1.4 % liver resection) in IDF, p=0.13) (Table 2) and was an independent prognostic factor (HR=0.32, 95 % CI [0.21–0.58], p<0.001), as well as an AFP score ≤ 2 (HR=0.65, 95 % CI [0.44–0.95], p=0.02) (Table 6).

Baseline predictive factors of mortality for BCLC C patients (Cox proportional hazard regression models).

*Number (percentage); °median [range].

ALD: alcoholic liver related disease; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; EV: esophageal varices; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic Liver disease; MELD score: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

+ In Milan HCC, Size of the largest lesion (mm), Tumor size > 5 cm were not entered in the multivariate analysis in order to avoid collinearity with AFP score ≤ 2, as well as Child-Pugh score to avoid collinearity with.

Patients from French Guiana exhibited worse clinical characteristics compared to those from other centers. Liver function was significantly more impaired, with 81 % of patients presenting a Child-Pugh score of B or C, compared to 44 % in Guadeloupe and 30 % in IDF (p<0.001). The median MELD score was 16 for French Guiana, compared to 10 for Guadeloupe and 9 for IDF (p<0.001). Patients from French Guiana were more frequently classified as BCLC stages D (49 % vs. 17 % in Guadeloupe and 5 % in IDF, p<0.001). They also had larger HCC (median size of the largest lesion: 100 mm vs. 37 mm and 36 mm, p<0.001), more vascular invasion (60 % vs. 27 % in Guadeloupe and 23 % in IDF, p<0.001), higher rates of extrahepatic metastases (42 % vs. 20 % and 9 %, p<0.001), and significantly elevated AFP levels (median: 530 ng/mL vs. 32 ng/mL and 13 ng/mL, p<0.001) (Supplementary Table 6). Moreover, patients in French Guiana were less likely to receive curative treatment, with 64 % receiving exclusively best supportive care, compared to 31 % in Guadeloupe and 17 % in IDF (p<0.001, Supplementary Table 7). Median OS was 2.2 months in French Guiana compared to 34.5 months in Guadeloupe and 22.8 months in IDF (p=0.02) (Fig. 1F).

4DiscussionThis study is the first to provide a detailed analysis of the prognosis, tumor characteristics, and liver function profiles of HCC patients in FOT. It revealed that HCC was diagnosed at more advanced stages and in patients with more impaired liver function in FOT compared to a tertiary center (IDF), significantly limiting curative treatment options. Additionally, mortality was significantly higher in FOT than in mainland France.

In the whole cohort, the median OS was significantly lower in FOT compared to IDF. However, no significant difference in OS was observed between IDF and FOT when stratified by BCLC classification. The higher proportion of BCLC-D cases in FOT, which are associated with shorter OS, likely explains the poorer outcomes in the global cohort. This finding was further supported by the multivariate analysis, which identified the BCLC-D stage as an independent predictor of increased mortality. These disparities were particularly marked in French Guiana, where 49 % of patients were classified as BCLC-D, compared to 17 % in Guadeloupe and 5 % in IDF. The outcomes observed in French Guiana differed significantly from those in Guadeloupe and IDF, with less favorable results characterized by more advanced disease stages, greater liver function impairment, and a higher frequency of best supportive care being administered. The situation of French Guiana closely mirrors that observed in Mayotte, highlighting regional disparities in disease progression and less access to curative treatments due to lack of specialists in these regions and sometimes, the need to cross the ocean to find them [21]. French Guiana and Guadeloupe differ significantly from the IDF region, particularly the Val-de-Marne locality where the tertiary center in this study is based. Socioeconomic conditions are more precarious in the FOT, with average household incomes of €10,990 in French Guiana, €15,770 in Guadeloupe, and €24,270 in IDF, and poverty rates of 50 %, 34 %, and 17.2 %, respectively [22–24]. Educational levels are also lower: 49.5 % of the population in French Guiana and 37.8 % in Guadeloupe have no qualifications, compared to 18.7 % in IDF, while only 34.1 % and 41.3 % hold baccalauréat degree or higher, versus 60.9 % in IDF [22–24]. Medical resources are scarcer in the FOT. In 2023, French Guiana has per 100,000 inhabitants 121 general practitioners (GPs) and 120 specialists, including 3 hepatogastroenterologists. In comparison, per 100,000 inhabitants, Guadeloupe has 145 GPs, 163 specialists (4 hepatogastroenterologists), and IDF has 1115 GPs, 2086 specialists, including 60 hepatogastroenterologists [25]. Access to care is further hindered by economic barriers, long wait times, and transport issues, with 28–30 % of residents in Guadeloupe and French Guiana forgoing medical care [26,27]. Public transport use is limited (2.8 % in French Guiana, 5.4 % in Guadeloupe vs. 48.5 % in IDF), and reliance on cars—often unaffordable for vulnerable populations—can further restrict access to healthcare, such as surveillance programs (22–24). Despite these observations, median OS in the entire cohort was comparable between Guadeloupe and IDF, possibly due to a higher rate of curative surgical treatments in Guadeloupe compared to French Guiana. In 2014, Guadeloupe began standardizing its multidisciplinary tumor board meetings with French metropolitan centers to evaluate patients' eligibility for liver transplantation. This initiative likely contributed to the increased access to surgical treatments observed in the current series, with 17 % and 8 %, of patients eligible for resection and liver transplantation, respectively, compared to only 12 % and 4 % respectively, in a previous study conducted prior to this period [28]. The situation in French Guiana is further complicated by a shortage of specialists in hepatology, radiology, oncology and surgery. Cancer care remains limited, both diagnostically and therapeutically. Until 2023, there were no practicing oncologists in the region, leading to the establishment of a partnership with an oncological center in Lyon (mainland France) as early as 2009. However, access to specialized care—requiring travel to mainland France—is limited to individuals with social security coverage, excluding a significant portion of the population, particularly those of foreign origin living in precarious conditions [29]. The average density of hepatogastroenterologists during the study period was just 1.6 per 100,000 inhabitants in French Guiana, compared to 4.5 per 100,000 in Guadeloupe [25]. This shortage likely impacted the quality of chronic liver disease management, contributing to higher rates of loss to follow-up, longer treatment delays (which may deter care-seeking), and overall poorer outcomes. A recent study found that nearly half (46.8 %) of patients with chronic HBV infection in French Guiana were lost to follow-up [30]. In French Guiana, a recent restructuring of the management of HCC since 2021, shortening the care circuit thanks to joint multidisciplinary tumor board meetings with French metropolitan centers and the arrival of new physicians specialized in interventional radiological procedures, and hepatogastroenterology will probably contribute to improving access to curative care in the future. In our study, the difference in OS across the cohort diminished after four years, likely due to the smaller number of patients in the FOT and the higher rates of liver transplantation and surgical resection in Guadeloupe.

In this series, we observed that, despite similar liver function and portal hypertension profiles between FOT and IDF, treatment approaches according to BCLC stage varied by region. Early- stage patients in FOT had more access to surgical treatments, while ablation was more commonly performed in IDF. These differences likely reflect the facilities and expertise available at each center. Additionally, the higher prevalence of HBV-related HCC in FOT may have influenced treatment strategies. Surgical approaches are often preferred in HBV patients due to fewer complications compared to those with metabolic syndrome, where surgery can be more challenging due to higher comorbidities and increased surgical risks [31].

Another interesting finding from this study is the comparable median OS for BCLC-B patients, despite significant differences in treatment strategies between IDF (where 28 % underwent ablation and 28 % received TACE) and FOT (where systemic treatment was used in 63 % of cases). This suggests that systemic therapies, particularly immunotherapy, could represent a promising alternative for this population, especially in centers where radiological treatments are unavailable. As suggested by BCLC algorithm, systemic therapies may also be better suited for patients with bilobar tumors involving over 50 % of the liver, infiltrative or poorly defined nodular tumors, or those with large vessel vascular invasion-conditions typically associated with reduced efficacy of TACE. These results emphasize the potential role of systemic treatments in broadening therapeutic options for intermediate-stage HCC patients in challenging clinical contexts [32].

Chronic HBV infection stands out as a primary contributor to HCC in the FOT, particularly in comparison to mainland France. Recent studies highlight that HBV-related HCC is not only more prevalent in the FOT (26.6 % vs. 9.6 %) but also more frequently observed, with a standardized incidence of 0.5 per 100,000 inhabitants in mainland France, 0.57 in Guadeloupe, and nearly double that—1.08—in French Guiana. Moreover, it tends to occur at a younger age, reflecting the endemic nature of HBV in these regions [19]. This pattern is particularly pronounced in areas like Mayotte, where nearly all cases of HCC are attributed to HBV, with the majority being diagnosed at advanced stages [21]. Similarly, French Guiana and Guadeloupe demonstrate a high burden of chronic HBV, classified as a medium-endemicity zone [11–15]. In French Guiana, several studies conducted in specific populations—and one in the general population—have reported a prevalence ranging from 2 % to 3 % [12,14,33]. In Guadeloupe, one study reported a seroprevalence of 1.5 % [11]. In contrast, the prevalence in the general population of mainland France is estimated at 0.3 % [34].The intense migratory patterns, especially in French Guiana and Mayotte, from neighboring countries with higher HBV prevalence, further amplify this issue [35]. Since its introduction in France in 1980 and its mandatory inclusion for infants in 2018, HBV vaccination has achieved over 90 % coverage among individuals under 15 in the FOT [36]. This effort represents a critical step in reducing HBV-related liver diseases, including HCC. However, addressing the ongoing burden requires more than vaccination alone. Effective strategies for early detection, comprehensive antiviral treatment programs, and public health initiatives tailored to the unique demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the FOT are essential. Although antiviral treatments have been shown to effectively reduce the risk of HCC in patients with HBV infection [37–39], we have previously reported in Guadeloupe that at the time of HCC diagnosis, only a small proportion of patients had been treated for chronic HBV infection [28], with 8 % of virosuppressed patients at HCC diagnosis. This is largely because the diagnosis of chronic HBV infection and HCC were concomitant. In French Guiana, a cohort study from 2015 to 2018 showed that antiviral therapy had been initiated in just 17 % of patients, with 8 % subsequently lost to follow-up [30]. By leveraging vaccination, improving healthcare access, and addressing underlying factors such as migration patterns and healthcare disparities, it is possible to mitigate the long- term impact of HBV and reduce the incidence of HCC in these territories. Interestingly, while the leading causes of HCC in the FOT were HBV and chronic alcohol consumption, a meta-analysis reported HCV as the leading cause in Latin America (48 %), followed by alcohol (22 %) and HBV (14 %) [40]. In a multicenter Latin American study (2005–2011), viral hepatitis was also the main etiology, followed by alcohol. HCC due to metabolic-associated liver disease was observed in only 5.5 % of cases, compared with 16 % in our cohort. Five-year survival in that study was 65 %, notably higher than in our population (40 %) [41].

Indeed, metabolic syndrome, encompassing obesity, type 2 diabetes, and related conditions, is an increasingly recognized driver of HCC globally, and the FOT are no exception. Both French Guiana and Guadeloupe face significant public health challenges due to high rates of obesity and diabetes [16]. Recent studies in French Guiana report a type 2 diabetes prevalence of nearly 10 % and obesity rates of 19 %, with 36 % of adults being classified as overweight [42,43]. Despite these statistics, MASLD appears less prevalent as an etiology of HCC in the FOT compared to mainland France. This paradox may be attributed to genetic predispositions or distinct environmental factors that influence disease progression in these populations. Nevertheless, the increasing burden of obesity and diabetes in the FOT warrants monitoring, as these conditions could lead to an increase in MASLD-related HCC in the coming decades. Data suggest lower rates of daily alcohol consumption and heavy binge drinking in these territories [17,18]. However, the interplay between alcohol use and other risk factors such as HBV infection or metabolic syndrome must not be overlooked, as combined etiologies can accelerate liver damage and tumorigenesis, as it is reported in Guadeloupe, where 71 % of patients with HCC had regular alcohol consumption [7]. Addressing these challenges requires a multi-pronged approach. Public health initiatives aimed at constraining obesity and diabetes, combined with educational campaigns to raise awareness about the risks of alcohol misuse, will be crucial in mitigating the impact of these risk factors on liver disease and HCC in the FOT.

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the relatively small sample size from FOT may limit the generalizability of our findings, as not all patients in the region were included in the analysis. Furthermore, many patients from French Guiana choose to leave it for mainland France for treatment after being diagnosed with cancer. Consequently, patients who underwent tests outside the hospital system or left the region are not represented in our cohort. This could lead to an underestimation of HCC cases and treatments, as those who leave are often in better general condition. Second, the retrospective nature of the study introduced missing data, particularly regarding access to antiviral therapy, despite the fact that HBV is a leading cause of HCC in FOT. This limitation restricts our ability to assess the impact of antiviral treatment on disease progression and outcomes. In addition, only one center was selected to represent mainland France. However, when comparing the characteristics of patients from the IDF center with preliminary results from the national multicenter French study—the CHIEF cohort, which aims to provide epidemiological and prognostic data on HCC—characteristics between IDF and CHIEF population were similar [10]. Finally, our study lacked detailed information on surveillance strategies and their implementation within the population. This gap prevents a comprehensive evaluation of how early detection practices might influence patient outcomes, a critical factor in improving prognosis for HCC patients. Despite these limitations, the present study is the first to provide such comparative data which reveal important areas where efforts are required to improve prognosis.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, HCC patients in FOT have a poorer prognosis compared to IDF, due to diagnoses at more advanced stages, limiting curative treatment options. These findings highlight the need for improved access to care and screening strategies for earlier diagnosis of HCC in FOT.

Author contributionsDrs. Aboikoni, Allaire, Ganne, and Gelu-Simeon had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of data and the accuracy of data analysis; Study concept and design: Drs. Aboikoni, Allaire, Ganne, and Gelu-Simeon; Acquisition of data: Drs. Aboikoni, Allaire, Busso, Ganne, and Gelu-Simeon, and Mrs Catherine; Analysis and interpretation of data: Drs. Aboikoni, Allaire, Ganne, and Gelu-Simeon; Drafting of the manuscript: Drs. Aboikoni, Allaire, Ganne, and Gelu-Simeon; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Drs. Aboikoni, Allaire, Louvel, Alogo A Nwatsok, Ngock, Ouni, Tangan, Zappa, Nacher, Douine, Drak Alsibai, Busso, Ganne, Gelu-Simeon, and Mrs Catherine; Statistical analysis: Dr. Allaire; Study supervision: Drs. Aboikoni, Allaire, Ganne, and Gelu-Simeon.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologiesAn AI-assisted English corrector was used to improve grammar and spelling in this manuscript.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

AA: none; MA: received travel and congress fees, and consulting fees or honoraria for lectures and presentations from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Gilead and Roche; DL: none; MAAN: none; PND: none; AO: none; LT: none; MZ: none; KDA: none; MD: none; MN: none; LC: none; CB: none; NG: received travel and congress fees, and consulting fees or honoraria for lectures and presentations from AbbVie, Bayer, Gilead, Intercept and Roche; MGS: received travel and congress fees from AbbVie and Ipsen.