Background and rationale. Epidemics of hepatitis B and C are a public health burden, and their prevalence in Brazil varies among regions. We determined the prevalence of hepatitis markers in an urban university population in order to support the development of a comprehensive program for HBV immunization and HBV/HCV diagnosis. Students, employees, and visitors (n = 2,936, 31 years IQR 24.5-50, female = 69.0% and 81.1% with at least 12 years of education) were enrolled from May to November 2013. Antibodies against hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs), against hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc), and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) were detected with enzyme immunoassays and anti-hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) antibodies with a chemiluminescence immunoassay. The results were confirmed with polymerase chain reaction for HCV and nucleic acid amplification test for hepatitis B virus (HBV).

Results. The overall prevalence of markers among the participants was 0.136% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.003-0.270) for HBsAg, 6.44% (95% CI: 5.55-7.33%) for anti-HBc, 50.8% (95% CI: 48.9-52.7%) for anti-HBs > 10 mIU/mL, and 0.44% (95% CI: 0.20-0.68) for anti-HCV. Almost 30.4% had anti-HBs titers > 100 mIU/mL. Participants with a detectable HCV viral load (n = 9) were infected with genotype 1a.

Conclusions. In an urban university population, in which 80% of participants had > 11 years of education, prevalence increased with age, and self-declared ethnicity for anti-HBc and with age, marital status and professional activity for anti-HCV antibodies. A periodical offer of HCV rapid testing should be implemented, and HBsAg rapid testing should be offered to individuals above 20 years of age.

Hepatitis B and hepatitis C viral infections are a serious public health problem that affects millions of people worldwide.1,2 The global distribution patterns of the infections are heterogeneous due to regional transmission characteristics combined with differences in the quality and availability of health services.2–4

The hepatitis B virus is a DNA virus, characterized by its high infectivity. The WHO fact sheet from July 2014,5 and also Gerlich6 mention that more than 240 million people have chronic (longterm) liver infections and more than 780,000 people die every year due to the acute or chronic consequences of hepatitis B. Although many drugs are now available to treat HBV chronic infections, ultimately, control of hepatitis B infection will only be achieved through universal vaccination of infants and adolescents.7

The hepatitis C virus is an RNA virus, of relative mutability, that is mostly transmitted through blood transfusion and sharing infected syringes by injecting drug users. WHO fact sheet from July 20145 informs that 130-150 million people globally have chronic hepatitis C infection, although Gower, et al.8 estimated a total global viraemic HCV infections at 80 (64-103) million. A significant number of those who are chronically infected will develop liver cirrhosis or liver cancer and 350,000 to 500,000 people die each year from hepatitis C-related liver diseases.5 No vaccine is currently available for hepatitis C, but for many individuals treatment can be successful and results in virus clearance.9

The estimated population of the Rio de Janeiro city in 2014 is of 6,453,682 inhabitants. In the last Brazilian demographic census (IBGE-2010), 2,960,954 were men (46.82%) and all were considered an urban population. In the National House Population Sample,10 individuals (color/race-self declaration) were White 53.6% (6,207,702); Mixed 33.6% (3,891,395); Black 12.3% (1,424,529); and Asian or Brazilian native (Amerindians) 0.5% (57,908).

A Brazilian nationwide cross-sectional survey of the prevalence and epidemiological patterns of hepatitis B and C infections conducted in 2010, have shown an heterogeneous distributions of these infections in the country.11 The Southeast region, where the State of Rio de Janeiro is located, has been categorized as low HBV endemic area while ranked second on HCV prevalence (1.27%) among the five regions of the country.

The Brazilian national vaccination program against HBV initiated candidly in the early 90’s with regional vaccination campaigns implemented in the Amazon region. In the following years, it was expanded to states with high endemicity of HBV infection and then to health care professionals. In 1998, vaccination of children under one year of age has been included in Brazil’s national infant immunization calendar. Since then, the national immunization program has expanded vaccination to individuals up to 49 years old.12

HCV screening for blood donations was introduced in Brazil in 1993, and since then blood banks have remained the most important source for HCV diagnosis. Patients presenting with signs and symptoms of liver disease are also tested for HCV infection in the health care units. However, in most instances this diagnosis is too late, as patients may have advanced liver disease or is too old to initiate therapy. The Brazilian government has recently launched a program to expand HCV diagnosis in the country by implementing HCV rapid testing in primary health units. This initiative aims to make an early diagnosis of HCV infection and consequently reduce the time to HCV treatment initiation.13

Aligned with these government initiatives, the Rio de Janeiro State University (Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, UERJ) has planned to launch a program to prevent HBV infection and to provide HCV diagnosis for the University community members.

As a first step to this approach, a cross-sectional study was developed to analyze hepatitis B and C infections and the associated socio-demographic and behavioral data amongst students, faculties, and servants of the University. Therefore, the aim of this study is to provide the University with reliable background information to support the development of a comprehensive program for HBV immunization and HBV/HCV diagnosis. These two interventions are pillars to prevent HBV infection, and to introduce proper HCV treatment among the university community. Once implemented, this program may serve as a model to policy makers and will certainly contribute to the country effort to mitigate the serious consequence of an advanced liver disease on the Brazilian public health care system.

Material and MethodsStudy design and data collectionDuring the period between May and November 2013, 3,044 individuals were enrolled on the study. Students, employees, and faculties of the UERJ campus in the Maracanã neighborhood, Rio de Janeiro, compose the study population. The campus is located in a privileged area of the municipality and about 15,000 people pass through it each day.

A booth was set up at the main hall of the University with space for individual interviews conducted by trained study members and blood collection carried out by health personnel. Data were collected by using a structured questionnaire. Study staff members applied one part of the questionnaire and address social and demographic characteristics (date of birth, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education level and professional activity). Information on gender and date of birth were mandatory as inclusion criteria. A second part, self-declared, was then applied addressing 14 questions on risk factors for HBV and HCV infections: use of illicit intravenous drugs, use of sniffed drugs, tattoo/body, number of sexual partner in the last year, piercing, dental treatment, surgery, history of blood transfusion, transplantation, hemodialysis, acupuncture, accidents involving biological materials, injectable medication, use of disposable material on nail care center, and use of own material on nail care center, as well as vaccination history for hepatitis B.

Of the 3,044 individuals enrolled, 108 (1.4%) with incomplete data were excluded from the study: 26 participants did not have enough sample volume to perform anti-HBs (n = 17) or anti-HBc (n = 9) assays; 17 individuals did not give information of the date of birth and; 65 participants returned the selfdeclared questionnaire with more than 10 blank answers out of 15 total questions.

Serological and molecular testsA sample containing 5 mL of anticoagulated whole blood was collected and processed to obtain about 2 mL of plasma that was aliquoted in two vials (1 mL each) and stored at -70 oC until testing. All samples were initially screened for: anti-HCV antibodies by an indirect chemiluminescence immunoassay, VITROS Anti-HCV assay (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Raritan, New Jersey, USA); antibodies against the hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) by a competitive enzyme immunoassay, Bioelisa Anti-HBc (Biokit S.A., Barcelona, Spain) and antibodies against the hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) by a quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay, Bioelisa Anti-HBs (Biokit S.A., Barcelona, Spain). Participants with anti-HBs antibodies level above 10 IU/mL were considered immune against HBV.

Samples reactive on HCV screening assay were further tested by a second sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay, Anti-HCV II immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) on the Cobas analyzer. Discordant samples between anti-HCV assays were considered non-reactive. Samples reactive on both immunoassay were then tested by an HCV viral load assay, Abbott Real Time HCV assay (Abbott Molecular Inc., Des Plaines, IL, USA). Regardless of the HCV viral load result, individuals with dual reactive samples on the immunoassays were considered infected. Detectable HCV levels on the viral load assay were interpreted as current HCV infection while undetectable levels of HCV viral load were interpreted as past and/or current infection, as a single negative HCV RNA result cannot determine infection status on individuals having intermittent viraemia.

All anti-HBc reactive samples were also tested by a second sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay, HBsAg II immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) on the Cobas analyzer. Discordant results between HBsAg immunoassays were considered a false-positive result of the first assay and no further testing was carried out. Dual reactive samples however were additionally tested by an HBV viral load assay, Abbott Real Time HBV assay (Abbott Molecular Inc., Des Plaines, IL, USA). Samples reactive on two immunoassays and with detectable level of HBV DNA on the viral load assay were interpreted as carrying HBV.

Statistical analysisThe study sample size was mainly based on the expected prevalence for anti-HCV in the Brazilian southeast region (anti-HCV prevalence was the smallest estimated prevalence among serological parameters). Desired width of one-half of the CI was estimated as the 30% of the prevalence. Prevalence with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) was calculated for each serological parameters.

A database was created with data from the 2,936 study participants on a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analyzed with the Epi InfoTM version 7.1.4.0 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, US, 2014). For univariate analysis, chisquare test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare serological parameters (anti-HBc, antiHBs, and anti-HCV) with risk factors and demographic variables. Variables that were associated with the serological parameters (p < 0.18) were further analyzed in a stepwise logistic regression model to identify those that were independently associated with outcome. Results were considered statistically significant when p-value < 0.05.

Ethical issuesThe study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee of Pedro Ernesto University Hospital (number 500.169). After written consent forms had been obtained, signed interviews and collection of blood sample were collected. During interview participants received and a unique participant number which allows them to access testing results (negative result only) on a study site at the internet after two weeks of enrollment. In case of positive results, participants were contacted by telephone and invited to come to the clinical pathology laboratory of the Policlinica Piquet Carneiro where they were counseled and referred to the infectious disease unit of the UERJ for further clinical evaluation.

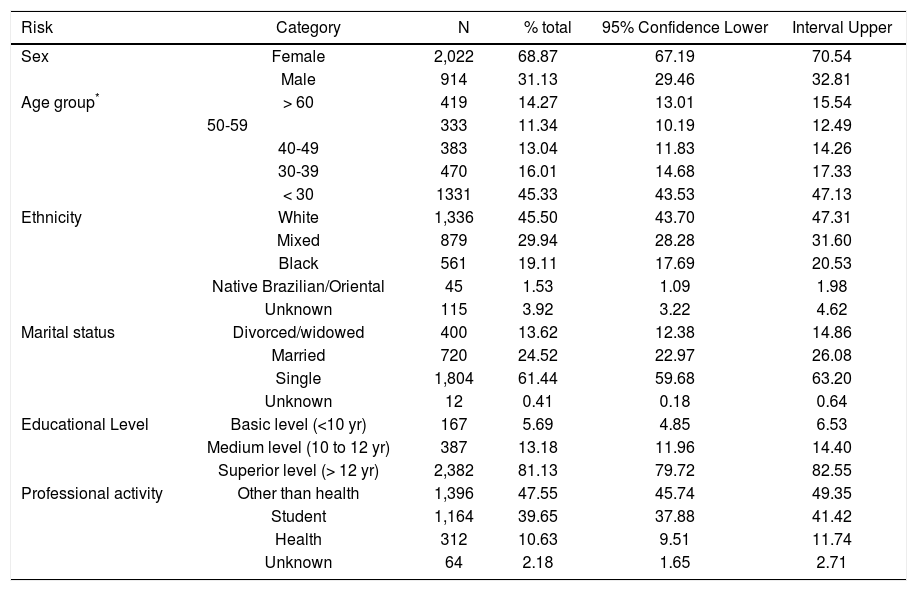

ResultsAfter interviewing 3,044 individuals for the 2013 UERJ Hepatitis Screening Campaign a complete data set were available and analyzed for 2,936 participants that were tested for hepatitis markers: anti-HCV, anti-HBs, anti-HBc and HBsAg for those that were anti-HBc reactive. Social and demographic data for those individuals are shown on table 1. Briefly, the median age was 31 years (IQR 24.5-50), and 69.0% of the population was female. All the participants self-reported their skin color/ethnicity as: White (45.5%), Mixed (29.9%), Black (19.1%), and 1.5% consider themselves as native Brazilian and/or Oriental’s descendants. Also, 61.4% were single, 24.5% were married and 13.6% either divorced or widowed; 81.1% of the participants had at least 12 years of education, and 13.2% and 5,7% had between 10 and 12 or less than 10 years of education. Finally, 10.6% were healthcare workers, 39.7% were students and 47.6% had professional activities other than healthcare.

Social demographic characterization of the 2013 UERJ Hepatitis Screening Campaign population.

| Risk | Category | N | % total | 95% Confidence Lower | Interval Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 2,022 | 68.87 | 67.19 | 70.54 |

| Male | 914 | 31.13 | 29.46 | 32.81 | |

| Age group* | > 60 | 419 | 14.27 | 13.01 | 15.54 |

| 50-59 | 333 | 11.34 | 10.19 | 12.49 | |

| 40-49 | 383 | 13.04 | 11.83 | 14.26 | |

| 30-39 | 470 | 16.01 | 14.68 | 17.33 | |

| < 30 | 1331 | 45.33 | 43.53 | 47.13 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 1,336 | 45.50 | 43.70 | 47.31 |

| Mixed | 879 | 29.94 | 28.28 | 31.60 | |

| Black | 561 | 19.11 | 17.69 | 20.53 | |

| Native Brazilian/Oriental | 45 | 1.53 | 1.09 | 1.98 | |

| Unknown | 115 | 3.92 | 3.22 | 4.62 | |

| Marital status | Divorced/widowed | 400 | 13.62 | 12.38 | 14.86 |

| Married | 720 | 24.52 | 22.97 | 26.08 | |

| Single | 1,804 | 61.44 | 59.68 | 63.20 | |

| Unknown | 12 | 0.41 | 0.18 | 0.64 | |

| Educational Level | Basic level (<10 yr) | 167 | 5.69 | 4.85 | 6.53 |

| Medium level (10 to 12 yr) | 387 | 13.18 | 11.96 | 14.40 | |

| Superior level (> 12 yr) | 2,382 | 81.13 | 79.72 | 82.55 | |

| Professional activity | Other than health | 1,396 | 47.55 | 45.74 | 49.35 |

| Student | 1,164 | 39.65 | 37.88 | 41.42 | |

| Health | 312 | 10.63 | 9.51 | 11.74 | |

| Unknown | 64 | 2.18 | 1.65 | 2.71 |

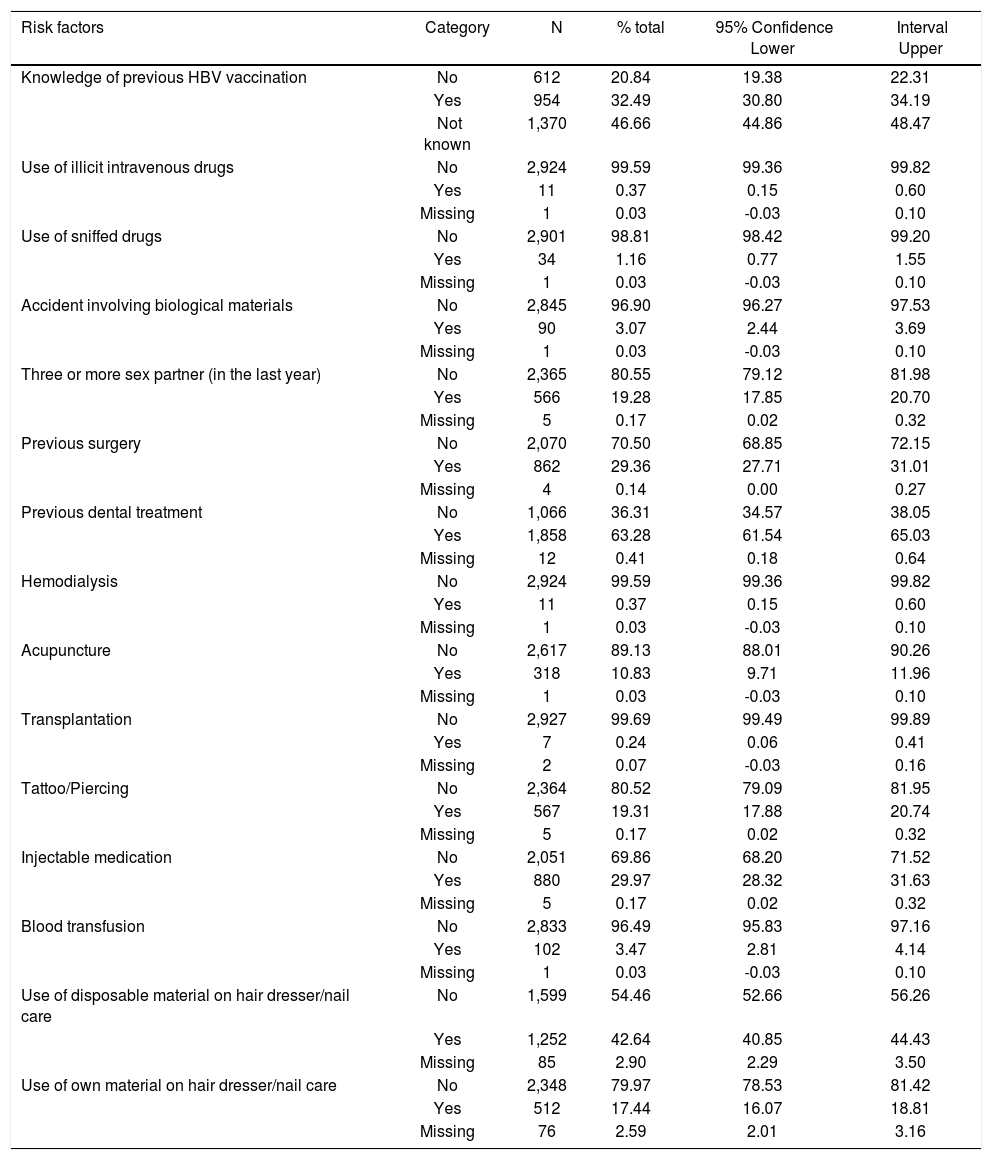

Questions relative to the self-declared questionnaire are shown on table 2. Five questions (use of intravenous drug, use of inhaled drugs, have undergone hemodialysis, blood transfusion or transplant), however, were excluded from the analysis of risk factors associated with anti-HBc and HCV reactivity because the number of individuals acknowledging risk factors were small and therefore variables did not have enough power (80%) to give a significant result.

Self-questionnaire answers of the 2013 UERJ Hepatitis Screening Campaign population.

| Risk factors | Category | N | % total | 95% Confidence Lower | Interval Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of previous HBV vaccination | No | 612 | 20.84 | 19.38 | 22.31 |

| Yes | 954 | 32.49 | 30.80 | 34.19 | |

| Not known | 1,370 | 46.66 | 44.86 | 48.47 | |

| Use of illicit intravenous drugs | No | 2,924 | 99.59 | 99.36 | 99.82 |

| Yes | 11 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.60 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.03 | -0.03 | 0.10 | |

| Use of sniffed drugs | No | 2,901 | 98.81 | 98.42 | 99.20 |

| Yes | 34 | 1.16 | 0.77 | 1.55 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.03 | -0.03 | 0.10 | |

| Accident involving biological materials | No | 2,845 | 96.90 | 96.27 | 97.53 |

| Yes | 90 | 3.07 | 2.44 | 3.69 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.03 | -0.03 | 0.10 | |

| Three or more sex partner (in the last year) | No | 2,365 | 80.55 | 79.12 | 81.98 |

| Yes | 566 | 19.28 | 17.85 | 20.70 | |

| Missing | 5 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.32 | |

| Previous surgery | No | 2,070 | 70.50 | 68.85 | 72.15 |

| Yes | 862 | 29.36 | 27.71 | 31.01 | |

| Missing | 4 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.27 | |

| Previous dental treatment | No | 1,066 | 36.31 | 34.57 | 38.05 |

| Yes | 1,858 | 63.28 | 61.54 | 65.03 | |

| Missing | 12 | 0.41 | 0.18 | 0.64 | |

| Hemodialysis | No | 2,924 | 99.59 | 99.36 | 99.82 |

| Yes | 11 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.60 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.03 | -0.03 | 0.10 | |

| Acupuncture | No | 2,617 | 89.13 | 88.01 | 90.26 |

| Yes | 318 | 10.83 | 9.71 | 11.96 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.03 | -0.03 | 0.10 | |

| Transplantation | No | 2,927 | 99.69 | 99.49 | 99.89 |

| Yes | 7 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.41 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.07 | -0.03 | 0.16 | |

| Tattoo/Piercing | No | 2,364 | 80.52 | 79.09 | 81.95 |

| Yes | 567 | 19.31 | 17.88 | 20.74 | |

| Missing | 5 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.32 | |

| Injectable medication | No | 2,051 | 69.86 | 68.20 | 71.52 |

| Yes | 880 | 29.97 | 28.32 | 31.63 | |

| Missing | 5 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.32 | |

| Blood transfusion | No | 2,833 | 96.49 | 95.83 | 97.16 |

| Yes | 102 | 3.47 | 2.81 | 4.14 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.03 | -0.03 | 0.10 | |

| Use of disposable material on hair dresser/nail care | No | 1,599 | 54.46 | 52.66 | 56.26 |

| Yes | 1,252 | 42.64 | 40.85 | 44.43 | |

| Missing | 85 | 2.90 | 2.29 | 3.50 | |

| Use of own material on hair dresser/nail care | No | 2,348 | 79.97 | 78.53 | 81.42 |

| Yes | 512 | 17.44 | 16.07 | 18.81 | |

| Missing | 76 | 2.59 | 2.01 | 3.16 |

Of the total 2,936 individuals analyzed, 189 were positive for anti-HBc antibodies, corresponding to a prevalence of 6.44% (95% CI: 5.55-7.33%). Of the reactive anti-HBc, 156 (82.5%) had anti-HBs levels greater than 10 IU/mL and therefore the HBV infection was considered resolved. Four individuals (2.1%) were chronically infected, as they carried HBsAg antigen and were negative for anti-HBs (< 10 IU/mL), resulting in an overall prevalence of HBV chronic infection of 0.136% (95% CI: 0.0030.270). A group of 28 individuals (14.8%) had reactivity against anti-HBc only, representing a prevalence of 0.95% (95% CI: 0.60-1.31). For these individuals, it was not possible to test samples for HBV DNA to rule out the possibility of an occult hepatitis B infection (OBI) as well as for a second antiHBc assay as an attempt to rule out a false-positive reactivity. Nevertheless, 14/28 samples has a CO/DO ratio above 2.0 and 10/28 had a CO/DO ratio above 5.0. In one individual (0.5%), all three HBV markers were positive (HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HBs) and further testing by NAT confirmed the presence of HBV DNA in this individual’s sample.

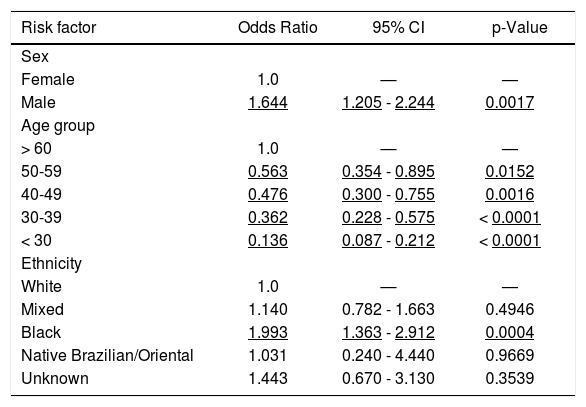

The univariate analysis conducted with all 189 anti-HBc reactive individuals showed that all demographic variables (namely; sex, age group, educational level, marital status, ethnicity, and professional activity) in addition to tattooing or whether ever had an acupuncture session were associated with anti-HBc reactivity (data not shown). However, on the logistic regression analysis the only variables that remained independently associated with anti-HBc reactivity were the demographic variables: sex, age group and ethnicity (Table 3). Overall, a black male at older age carries a greater risk of having had an HBV infection. Adjusted for age, and compared to the white female reference group, the black male group has a 3.28 greater likelihood to be anti-HBc positive.

Anti-HBc-Multivariate analysis (n = 2,936) of the 2013 UERJ Hepatitis Screening Campaign population.

| Risk factor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.0 | — | — |

| Male | 1.644 | 1.205 - 2.244 | 0.0017 |

| Age group | |||

| > 60 | 1.0 | — | — |

| 50-59 | 0.563 | 0.354 - 0.895 | 0.0152 |

| 40-49 | 0.476 | 0.300 - 0.755 | 0.0016 |

| 30-39 | 0.362 | 0.228 - 0.575 | < 0.0001 |

| < 30 | 0.136 | 0.087 - 0.212 | < 0.0001 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 1.0 | — | — |

| Mixed | 1.140 | 0.782 - 1.663 | 0.4946 |

| Black | 1.993 | 1.363 - 2.912 | 0.0004 |

| Native Brazilian/Oriental | 1.031 | 0.240 - 4.440 | 0.9669 |

| Unknown | 1.443 | 0.670 - 3.130 | 0.3539 |

To figure out the number of HBV vaccinated individuals in study population, all anti-HBc positive individuals were removed from the analysis. In these individuals, the presence of anti-HBs is likely due to a resolved HBV infection. However, anti-HBs attributed to HBV vaccination could not be formally excluded, therefore and to avoid confusion in the analysis of the HBV vaccination correlates, the whole anti-HBc positive individuals were left out. Of the 2,747 individuals that had never been exposed to HBV, 1,395 (50.8%, 95% CI: 48.9-52.7%) had antiHBs levels above 10 IU/mL, and 836 individuals (30.4%, 95% CI: 28.7-32.2%) had anti-HBs levels above 100 IU/mL.

Approximately half of the total individuals, 1,445/ 2,747 (52.6%) have responded the question about knowledge of their vaccine status. Among the individuals, which answered that, they knew they were vaccinated against HBV 75.4% had anti-HBs levels above 10 IU/mL while among individuals that answered they had not been vaccinated, and 79.8% indeed were not vaccinated (Table 4).

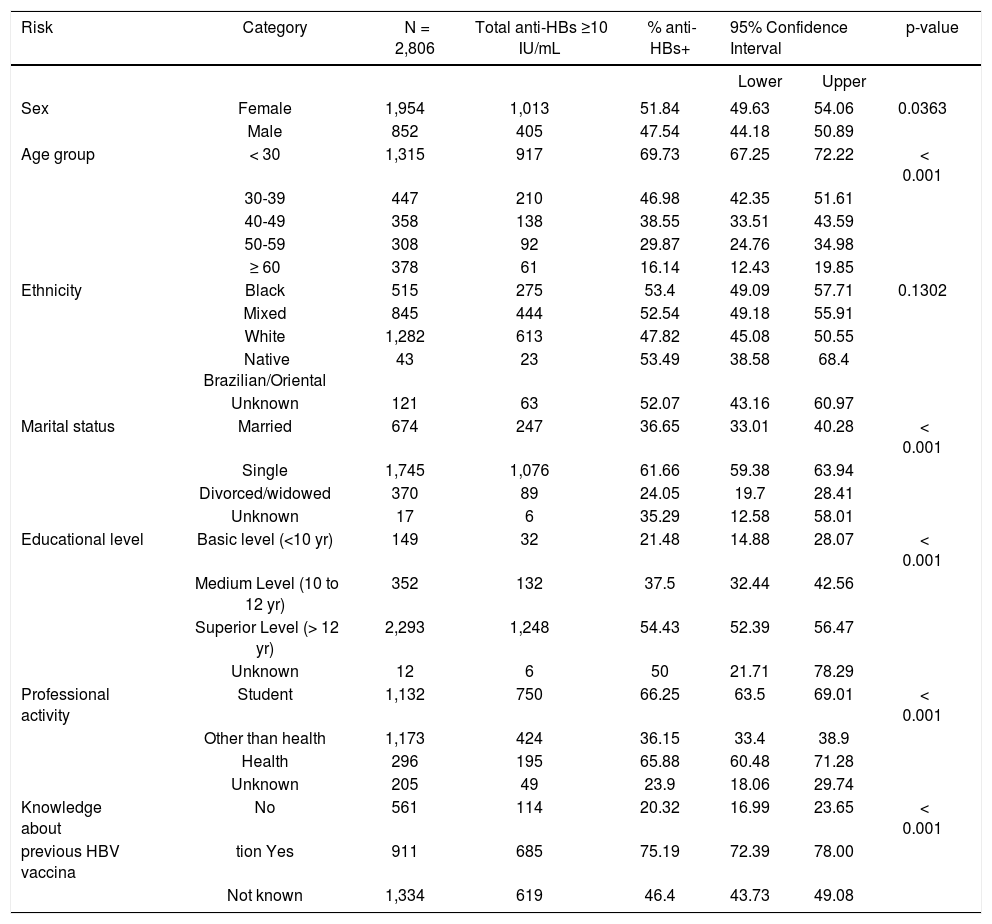

Univariate analysis (excluding anti-HBc positive individuals) of vaccination for hepatitis B virus (anti-HBs > 10 IU/mL) of the 2013 UERJ Hepatitis Screening Campaign population.

| Risk | Category | N = 2,806 | Total anti-HBs ≥10 IU/mL | % anti-HBs+ | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Sex | Female | 1,954 | 1,013 | 51.84 | 49.63 | 54.06 | 0.0363 |

| Male | 852 | 405 | 47.54 | 44.18 | 50.89 | ||

| Age group | < 30 | 1,315 | 917 | 69.73 | 67.25 | 72.22 | < 0.001 |

| 30-39 | 447 | 210 | 46.98 | 42.35 | 51.61 | ||

| 40-49 | 358 | 138 | 38.55 | 33.51 | 43.59 | ||

| 50-59 | 308 | 92 | 29.87 | 24.76 | 34.98 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 378 | 61 | 16.14 | 12.43 | 19.85 | ||

| Ethnicity | Black | 515 | 275 | 53.4 | 49.09 | 57.71 | 0.1302 |

| Mixed | 845 | 444 | 52.54 | 49.18 | 55.91 | ||

| White | 1,282 | 613 | 47.82 | 45.08 | 50.55 | ||

| Native Brazilian/Oriental | 43 | 23 | 53.49 | 38.58 | 68.4 | ||

| Unknown | 121 | 63 | 52.07 | 43.16 | 60.97 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 674 | 247 | 36.65 | 33.01 | 40.28 | < 0.001 |

| Single | 1,745 | 1,076 | 61.66 | 59.38 | 63.94 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 370 | 89 | 24.05 | 19.7 | 28.41 | ||

| Unknown | 17 | 6 | 35.29 | 12.58 | 58.01 | ||

| Educational level | Basic level (<10 yr) | 149 | 32 | 21.48 | 14.88 | 28.07 | < 0.001 |

| Medium Level (10 to 12 yr) | 352 | 132 | 37.5 | 32.44 | 42.56 | ||

| Superior Level (> 12 yr) | 2,293 | 1,248 | 54.43 | 52.39 | 56.47 | ||

| Unknown | 12 | 6 | 50 | 21.71 | 78.29 | ||

| Professional activity | Student | 1,132 | 750 | 66.25 | 63.5 | 69.01 | < 0.001 |

| Other than health | 1,173 | 424 | 36.15 | 33.4 | 38.9 | ||

| Health | 296 | 195 | 65.88 | 60.48 | 71.28 | ||

| Unknown | 205 | 49 | 23.9 | 18.06 | 29.74 | ||

| Knowledge about | No | 561 | 114 | 20.32 | 16.99 | 23.65 | < 0.001 |

| previous HBV vaccina | tion Yes | 911 | 685 | 75.19 | 72.39 | 78.00 | |

| Not known | 1,334 | 619 | 46.4 | 43.73 | 49.08 | ||

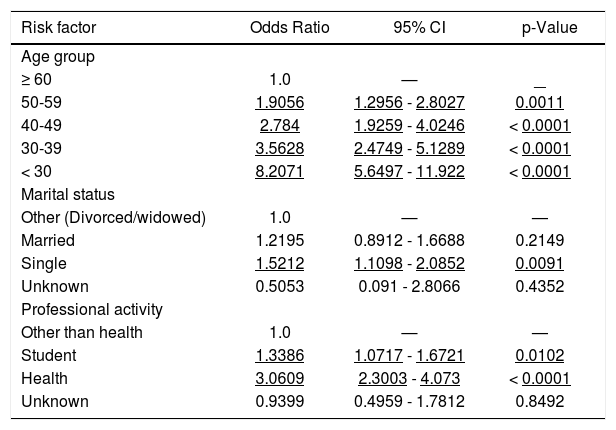

Demographic variables were analyzed against HBV vaccine status and all of them came out associated with HBV immunity. The logistic regression analysis however retained only age group, marital status and professional activity as independent variables associated with HBV immunity (Table 5). Being a single student or a health care worker at younger age were associated with anti-HBs positivity and therefore to protection against HBV infection. For instance, when adjusted for age, and compared to the widow/divorced person whose professional activity is other than a health care reference group, a single health care worker or a single student groups have a 4.66 and 1.43 greater chance to be protected from HBV infection, respectively.

Anti-HBs - Multivariate analysis* (n = 2,747) of the 2013 UERJ Hepatitis Screening Campaign population.

| Risk factor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | |||

| ≥ 60 | 1.0 | — | — |

| 50-59 | 1.9056 | 1.2956 - 2.8027 | 0.0011 |

| 40-49 | 2.784 | 1.9259 - 4.0246 | < 0.0001 |

| 30-39 | 3.5628 | 2.4749 - 5.1289 | < 0.0001 |

| < 30 | 8.2071 | 5.6497 - 11.922 | < 0.0001 |

| Marital status | |||

| Other (Divorced/widowed) | 1.0 | — | — |

| Married | 1.2195 | 0.8912 - 1.6688 | 0.2149 |

| Single | 1.5212 | 1.1098 - 2.0852 | 0.0091 |

| Unknown | 0.5053 | 0.091 - 2.8066 | 0.4352 |

| Professional activity | |||

| Other than health | 1.0 | — | — |

| Student | 1.3386 | 1.0717 - 1.6721 | 0.0102 |

| Health | 3.0609 | 2.3003 - 4.073 | < 0.0001 |

| Unknown | 0.9399 | 0.4959 - 1.7812 | 0.8492 |

The initial screening with the VitrosECi antiHCV EIA resulted in 35 repeat reactive samples, the majority of which with a low optical density/cutoff (OD/CO) ratio. All these samples were further tested by the Roche anti-HCV EIA and only 13 were positive in both assays. Interestingly, all 13 samples had a high OD/CO ratio on the initial VitrosECi screening assay. Overall, the HCV prevalence was 0.44% (95% CI: 0.20-0.68%).

The thirteen samples were submitted to the Abbott HCV viral load assay (Abbott Real Time HCV assay) and nine (69.2%) had detectable HCV-RNA with a median of 5.41 Log IU/mL (ranging from 3.00 to 6.28 Log IU/mL). Five samples were genotyped as 1a, but for the other four there was not enough sample left for genotyping.

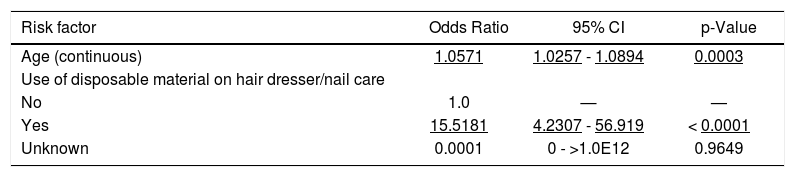

Variables associated with HCV positivity on the univariate analysis were age (as continuous variable), educational level, professional activity, previous surgery, previous dental treatment, accident involving biological materials, and use of disposable material on hair dresser/nail care. Although most of these variables had been previously associated with HCV infection, the only two variables that kept independent association with HCV infection on the logistic regression final model were age and use of disposable material on hair dresser/nail care (Table 6). Surprisingly, use of own disposable material increases the risk for HCV infection, a result that is counter common sense. We may suppose that these individuals had previous knowledge of their HCV status, so had used their own material to protect others.

Anti-HCV - Multivariate analysis of the 2013 UERJ Hepatitis Screening Campaign population.

| Risk factor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (continuous) | 1.0571 | 1.0257 - 1.0894 | 0.0003 |

| Use of disposable material on hair dresser/nail care | |||

| No | 1.0 | — | — |

| Yes | 15.5181 | 4.2307 - 56.919 | < 0.0001 |

| Unknown | 0.0001 | 0 - >1.0E12 | 0.9649 |

We then repeated the logistic regression analysis excluding this variable but again the only variable that remained associated with HCV infection was age (OR 1.06, 95% CI: 1.03-1.09). Accordingly, the estimated odds ratio for an increase of 10 years in age is 1.75 (95% CI: 1.29-2.36).

Finally, one 61 years-old woman has markers associated with both HCV and HBV infections. While she is an HCV chronic carrier with 6.27 log IU/mL and genotype 1a, she is anti-HBc and anti-HBs (greater than 100 IU/mL) positive, and therefore has resolved the HBV infection.

DiscussionThe population sampled for the study certainly differs from the general Brazilian population, and by color/race from the Rio de Janeiro census of 2010, but is clearly representative of the University community as characterized by: 45% of individual’s age range from 16 to 30 years, 61% are single and most (81%) has more than 12 years of education. In the last 10 years, the University has implemented a system to privilege access to Black/Mixed population, therefore the proportion of these groups is higher than the Rio de Janeiro population (19.1 x 12.3%). This young and well-educated population stratum gives a good opportunity to implement education and preventive measures aiming to curb HBV and HCV infections.14 Moreover, it represents a larger sample (n = 2,936) than that projected by Ximenes, et al.11 for an estimated Rio de Janeiro population between 20 and 69 years old of 4,174,528 individuals (n = 1,300).

The prevalence for HBsAg marker was 0.136% (95% CI: 0.003-0.270) and may represents chronic infections because all individuals also carries antiHBc antibodies and are negative for anti-HBc IgM. This prevalence is about half of the one described for first time blood donors in two southeast cities, São Paulo and Belo Horizonte in 2013, with 0.213% and 0.279%, respectively.15 Clearly, difference in individuals aged under 30 years (46 and 44% for Belo Horizonte and São Paulo, respectively) does not explain the difference in HBsAg prevalence between blood donors and this study population. However, female gender (36 and 38% for Belo Horizonte and São Paulo, respectively) which is about half of the one described for the population under study, as well as other factors may account for this difference.

The prevalence for anti-HBc antibody was 6.44% (95% CI: 5.55-7.33%), a value that is comparable with the 6.33% found for the southeast region, according to the nationwide cross-sectional survey conducted in Brazil in 2010. 16 In this survey, the frequency of anti-HBc + anti-HBs antibodies was not described but in the university community, 156 out of 2,936 individuals (5.31%) had both antibodies, suggesting that 82.5% of the anti-HBc positive individuals had recovered from HBV infection. In addition, 28 individuals had anti-HBc only antibodies and at least 14 had a CO/DO ratio above 2.0. For the remaining half with CO/DO ratio below 2.0, it was not possible to rule out anti-HBc false-reactivity but waning anti-HBc titer of a resolved HBV infection should be considered. Therefore, it is likely that a fraction of these 28 individuals with anti-HBc only antibodies may represent an OBI.

We have also found an individual carrying three HBV serological marker (HBsAg, anti-HBc and antiHBs) in addition to HBV DNA. The combination of these markers is not frequently found but has been described by others.17,18 However, the biological basis for this phenomena is still under dispute but mechanisms include:

- •

The convalescent phase after acute HBV infection when declining levels of HBsAg may coexist with rising levels of anti-HBs.

- •

Presence of HBsAg escape mutant19 and

- •

Presence of low affinity non-neutralizing anti-HBs antibodies.20

Unfortunately, it was not possible to follow up the disease course or to obtain a new sample from this individual in order to clarify the mechanism that led to this serological profile.

Whether the presence of anti-HBc only marker is a false-positive result or an OBI, vaccination of these individuals may help clear the virus for those with OBI, as has been shown by others21,22 and likewise induce immunity for those that were indeed anti-HBc false-positive.

Factors associated with anti-HBc positivity, male gender (OR = 1.64), black ethnicity (OR = 2.0) and a trend toward increasing age, have previously been reported to be associated with HBV infection in Brazil.16,23,24 In this particular, the university community is no different from the Brazilian general population.

Of the total of 2,747 individuals anti-HBc negative, nearly half (50.8%) has anti-HBs antibodies above 10 IU/mL and 30.4% has anti-HBs antibodies above 100 IU/mL. This is relevant, because the vaccine coverage among the vaccinated population in southeast of Brazil is 39.83%.11 Factors independently associated with HBV vaccination were being single (OR = 1.52), student (OR = 1.34), health worker (OR = 3.06) and a trend toward lower ages.

The question whether participants have knew their HBV vaccine status had a reliable result for those answering that has never been vaccinated (negative predictive value of 79.8%), therefore, from the programmatic point of view, vaccination, without any anti-HBs testing may be justifiable and cost effective.

In this study, the prevalence of anti-HCV was 0.44% (95% CI: 0.20-0.68%), whereas in a nationwide cross-sectional survey the prevalence for HCV in Southeast Brazil was 1.27%.25 Age (as continuous variable) was the only variable independently associated with HCV infection and therefore this 2.9 times difference in the HCV prevalence can be attributed to lower age of the university community participants. In fact, we have not found any HCV-infected individuals with ages lower than 30 years old, an age range that represents 45.3% of the study participants.

Of the variable that came out associated with the serological parameters after the multivariate analysis, it is noteworthy to mention the increasing risk for HBV (anti-HBc) and HCV infection with age, as has been reported in the Brazilian nationwide crosssectional survey11 and also in the international literature.2,6 Moreover, consistently with the increasing HBV infection risk with age, was decreasing anti-HBs positivity with increasing age.

In addition to age, other variables associated with anti-HBc and anti-HBs seropositivity, allowed us to propose strategies for HBV vaccination, and for HBV and HCV testing and eventually treatment, within the university, as discussed below.

The national immunization program for young adults has initiated only in 1998, thus, individuals above 16 years of age may not have had the opportunity to be vaccinated against HBV.7,26–30 This population’s age matches exactly with the one that now is part of the University community-students, faculties or servants. The HBV vaccination program therefore could include anyone above 20 years of age that reported has not been previously vaccinated. Particularly, a group of non-healthcare worker should be encouraged to be vaccinated, since they may have less access to the information on HBV infection and its consequence to their health.

One of the study limitations was the data reported and that were collected by self-declared questionnaires. Lack of sufficient privacy may have induced participants to give false or no answer to sensitive risk questions. This was particularly relevant for the two drug use related questions, which had to be excluded from the risk analysis due to small number of individuals that admitted to belong to these risk categories. In addition, questions related to the previous history of blood transfusion, transplantation or hemodialysis did not reach reasonable number of answer, but in this case due to the low risk event in this rather young study population. Finally, even though it was a linked study (all tests results were available to all participants) it was difficult obtaining a second blood sample from most seropositive individuals. Access to second sample would have allowed performance of HBV and HCV viral load to confirm chronic HCV infection and to access the presence of occult hepatitis B infection for those with reactivity to antiHBc only.

In spite of these limitations, this study provided some important information to develop a more comprehensive health-directed infection-prevention policies, including immunization, education, screening, and treatment within the university.14,27 These new policies will help expand the program that has recently begun which includes offering biannual anti-HBs testing to all healthcare professionals and to demand the hepatitis B vaccine status to students entering training in the clinical pathology service.

When conceived, the hepatitis B and C prevention program for the University community had this study as the first approach to acquire baseline as well as demographic information of the target population. This decision proved to be correct and the initial program design will now be adjusted according to the data gathered from the study. We hope this program building strategy can become a model to other communities at large.

The ultimate goals of these programs are to prevent infection and control disease progression for those already infected and, consequently, improve the quality of life of those infected by HBV or HCV as well as decrease costs for the public health sector.

A recently launched national program to expand hepatitis B and C diagnosis aims to initiate early treatment31 and therefore reduce liver disease progression. Aligned with this national initiative, a periodical offer of HCV rapid testing in the university campus should be implemented, especially to those at older age. This is the group likely to be infected and testing would be the first step to access healthcare, and ultimately to treatment. As for HCV, HBsAg rapid testing should be offered to individuals above 20 years of age, as they have less likelihood to have been vaccinated at birth. The black male subgroup would deserve a closer attention due to their greater chance to be HBV infected.

Abbreviations- •

anti-HBc: antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen.

- •

anti-HBs: antibodies against hepatitis B surface antigen.

- •

anti-HCV: antibodies against hepatitis C virus.

- •

HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen.

- •

HBV: hepatitis B virus.

- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

- •

HLA-UERJ: Laboratory of Histocompatibility and Cryopreservation, UERJ.

- •

UERJ: Rio de Janeiro State University.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

AcknowledgementsWe thank the laboratory staff of Serviço de Patologia Clínica da Policlínica Piquet Carneiro (CAPSULA), da Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, and Laboratório de Virologia Molecular da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

We thank Brazil Health Ministry - Departamento de DST, AIDS e Hepatites Virais for providing reagents and kits to the campaign. This study was partly funded with grants from Brazil Research Council (CNPq) and Rio de Janeiro Research Agency (FAPERJ).