Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy (CCM) has been recognized as a significant complication of end-stage liver disease (ESLD) for decades. Kowalski et al.(1953) identified a notable cardiovascular feature in ESLD: hyperdynamic function, characterized by reduced systemic vascular resistance and increased cardiac output [1]. Observations by Regan et al. [2] over five decades ago highlighted cardiac dysfunction in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, indicating early recognition of cardiac involvement in liver disease. Additionally, structural cardiac alterations can arise from cirrhosis independently of underlying conditions. Lee [3] introduced the term 'cirrhotic cardiomyopathy' (CCM) over three decades ago, shedding light on the chronic cardiac dysfunction present in individuals with cirrhosis.

The exact determinants of CCM have not been clearly elucidated. Despite not fully understanding its cellular and pathogenic foundations, the diagnosis and management of CCM have been hampered by a lack of universally accepted criteria, even though the initial diagnostic criteria for cirrhotic cardiomyopathy were established in 2005 at the Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology [4,5]. Significant strides in echocardiography, particularly in tissue Doppler imaging, over the past 15 years have enriched our comprehension of cardiac abnormalities, including cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. This imaging modality facilitates meticulous evaluations of cardiac function at the tissue level, providing insights into the structural and functional alterations within the hearts of cirrhotic individuals. Consequently, novel diagnostic criteria for cirrhotic cardiomyopathy have recently emerged in 2020, incorporating markers indicative of both diastolic and systolic dysfunction, as proposed by the Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy Consortium (CCC) [6].

The reported prevalence of CCM in the literature exhibits considerable variation, ranging from 6 % to 70 % among cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplantation [3]. However, this percentage is subject to change due to the emergence of new diagnostic criteria, leaving it currently uncertain [7]. Recently, Liu et al. reported a prevalence of 35.5 % in cirrhotic patients who were evaluated prior to TIPS placement [8]. Hu et al. conducted an extensive study, revealing a prevalence rate of 24.4 % [9], while the study by Ali and colleagues reported a lower prevalence of 17.5 % [10]. The study by Madhumita, focusing on patients with hepatorenal syndrome, reported a similar prevalence of 24.3 % [11], reflecting the importance of population-specific factors in determining prevalence rates. A major outlier is the study by Singh et al. [12], where the prevalence was remarkably high, reaching almost 85 % when applying the new criteria, with the majority of patients presenting a GLS <18 %. The explanation for this very high prevalence remains unclear although differences in study populations may be partly responsible.

The presence of CCM significantly increases the risk of pre-liver transplantation mortality and complications associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) and hepatic encephalopathy (HE) [12]. Studies have demonstrated that left atrial dysfunction prior to TIPS placement is an independent predictor of mortality [13], with some studies further identifying the presence of CCM in patients with hepatorenal syndrome, ACLF, and severe sepsis as an independent factor associated with non-response to terlipressin and increased mortality [11,14]. Furthermore, evidence published by Izzy suggests that CCM also substantially elevates the risk of post-transplant cardiovascular disease [15].

The aim of this study is to assess the prevalence of CCM in a population of decompensated cirrhotic patients undergoing liver transplantation evaluation, describe their clinical characteristics, and evaluate its association with mortality in the pre- and post-transplant periods.

2Materials and methods2.1Study design and patientsA retrospective analysis was conducted on a prospective database of consecutive patients aged 16 and older with a diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis of any etiology, who were evaluated and placed on the waiting list for liver transplantation at El Cruce Hospital in Florencio Varela, Buenos Aires, from June 2019 to June 2023.

Patients with any of the following conditions were excluded: non-cirrhotic patients; previously diagnosed structural heart disease of other etiology (including primary or secondary cardiomyopathy and moderate to severe valvulopathies); coronary artery disease; portopulmonary syndrome; hepatocellular carcinoma outside transplantability criteria; and those with an intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS).

The history of coronary artery disease was obtained through a targeted medical interview. In patients with regional wall motion abnormalities on echocardiography, left heart catheterization was performed.

2.2Assessment of cirrhosisThe diagnosis of cirrhosis was confirmed through histological or unequivocal biochemical and imaging tests. Decompensation of cirrhosis was defined by the presence of clinical complications such as esophageal variceal bleeding, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome.

2.3Echocardiographic assessment of cardiac functionThe echocardiographic studies were conducted by three cardiologists with expertise in the field, utilizing Philips EPIQ CVx equipment (software versions: 7.0.5, 9.0.1, 9.0.3) and a sectorial S5–1 transducer. Data acquisition was performed using multiple imaging modalities, including M-mode, color M-mode, two-dimensional imaging, color Doppler, pulsed Doppler, continuous Doppler, tissue Doppler, and strain imaging.

2.4Definition and diagnostic criteriaFollowing the criteria proposed by the Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy Consortium in 2020, CCM was defined as:

- -

Diastolic dysfunction was defined as meeting at least 3 of the following criteria: left atrial volume index (LAVI) > 34 ml/m², septal e’ 〈 7 cm/sec or lateral e’ < 10 cm/sec, tricuspid regurgitant maximum velocity 〉 2.8 m/sec, or a ratio of early diastolic transmitral flow to early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity (E/e’) ≥ 15.

- -

Systolic dysfunction was defined as meeting at least one of the following criteria: left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 50 % or global longitudinal strain (GLS) with an absolute value < 18 %.

A patient was classified as having cirrhotic cardiomyopathy (CCM) if they met the criteria for either systolic dysfunction, diastolic dysfunction, or both.

In cases where diastolic dysfunction was indeterminate (i.e., meeting 2 out of 4 criteria), as proposed by the CCC [6], an additional assessment was conducted. This assessment included at least two of the following: Valsalva maneuver, flow propagation velocity by color M-mode, pulmonary vein pressures, isovolumetric relaxation time and left ventricular longitudinal strain. Patients who demonstrated diastolic dysfunction in any of these additional assessments were classified as having CCM.

2.5Demographic and clinical data collectionDemographic and clinical data for the patients in the study, including disease etiology, smoking status, use of beta-blockers (BB), and pre-transplant hepatic decompensation events, were extracted from the patients' medical records through manual review and verification. Blood tests, including complete blood count, liver function tests, electrolytes, creatinine, prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), and albumin, were also obtained. The severity of cirrhosis was assessed using the Model for End-stage Liver Disease-Na (MELD-Na).

Additional clinical data were obtained through database extraction.

2.6Causes of mortalityThe causes of mortality on the waiting list were evaluated among patients with and without CCM and were defined as follows:

- -

Cardiovascular Causes of Death: Cardiovascular causes of death were defined as instances where the patient's death was attributed to a Major Adverse Cardiovascular Event (MACE). MACE includes events such as myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, arrhythmia, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death.

- -

Decompensation of Cirrhosis: Deaths due to decompensation of cirrhosis are defined as cases where the patient experienced significant clinical deterioration directly attributed to complications associated with cirrhosis. These complications include, but are not limited to, variceal hemorrhage, hepatic encephalopathy, refractory ascites, hepatorenal syndrome, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

- -

Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC):

- -

* Patients with HCC at BCLC stage 0 or A who died due to cirrhosis decompensation or other unrelated causes were not included in the group of patients who died from HCC.

* For patients with BCLC stage D, the cause of death was considered related to HCC, regardless of the specific cause.

* For patients with BCLC stage B or C, the cause of death was evaluated individually, taking into account tumor stage, Child-Pugh score, and performance status.

- -

Other Causes of Death: Deaths from causes not described above were categorized as "other".

- -

Unknown Cause of Death: Cases where the cause of death is unknown or could not be determined.

- -

The causes of post-transplant death were also evaluated in both groups

Continuous variables with a normal distribution are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). Non-parametric distributions are described by medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. The Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare continuous variables. Categorical variable analysis was performed using the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test.

Survival curves for the two groups were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with differences compared using the Log-rank test. The association between time-to-event outcomes and covariates was estimated using separate univariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. Variables with a univariate p-value <0.15 were then included in a multivariable Cox regression analysis to identify independent predictors of mortality. Subjects were considered at risk from the time of listing until they experienced the event of interest or were censored. Censoring occurred at the last follow-up time or due to an event that precluded the event of interest.

All analyses were performed using R statistical software version 4.2.1. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.8Ethical statementsThe study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (and its later amendments) and received prior approval from the Comité de Ética en Investigación, Hospital de Alta Complejidad en Red El Cruce Néstor Kirchner (Florencio Varela, Buenos Aires, Argentina), as documented in the approval letter dated May 14, 2024 (Approval ID: not applicable). Written informed consent was not required by the Ethics Committee due to the retrospective design and the use of de-identified data.

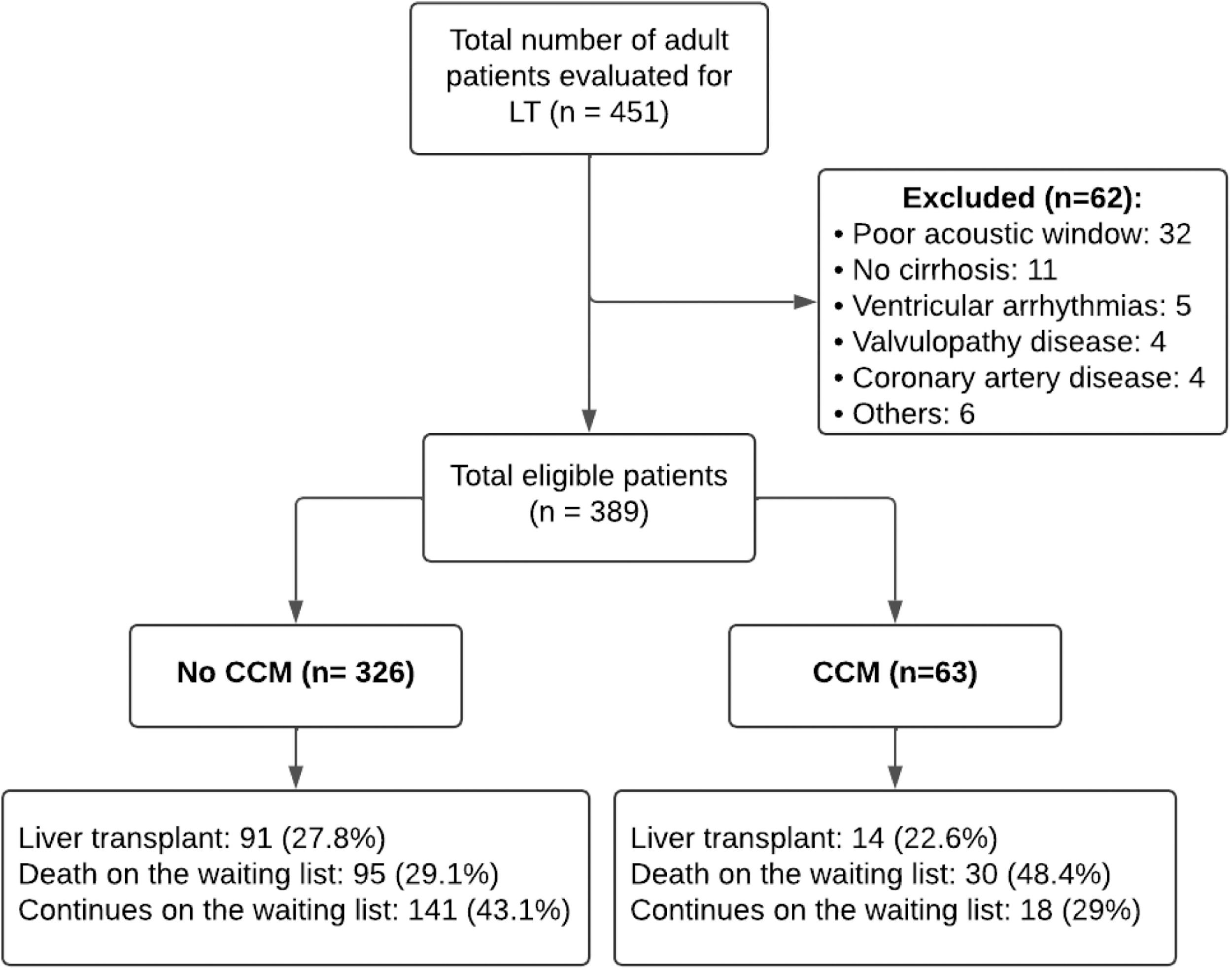

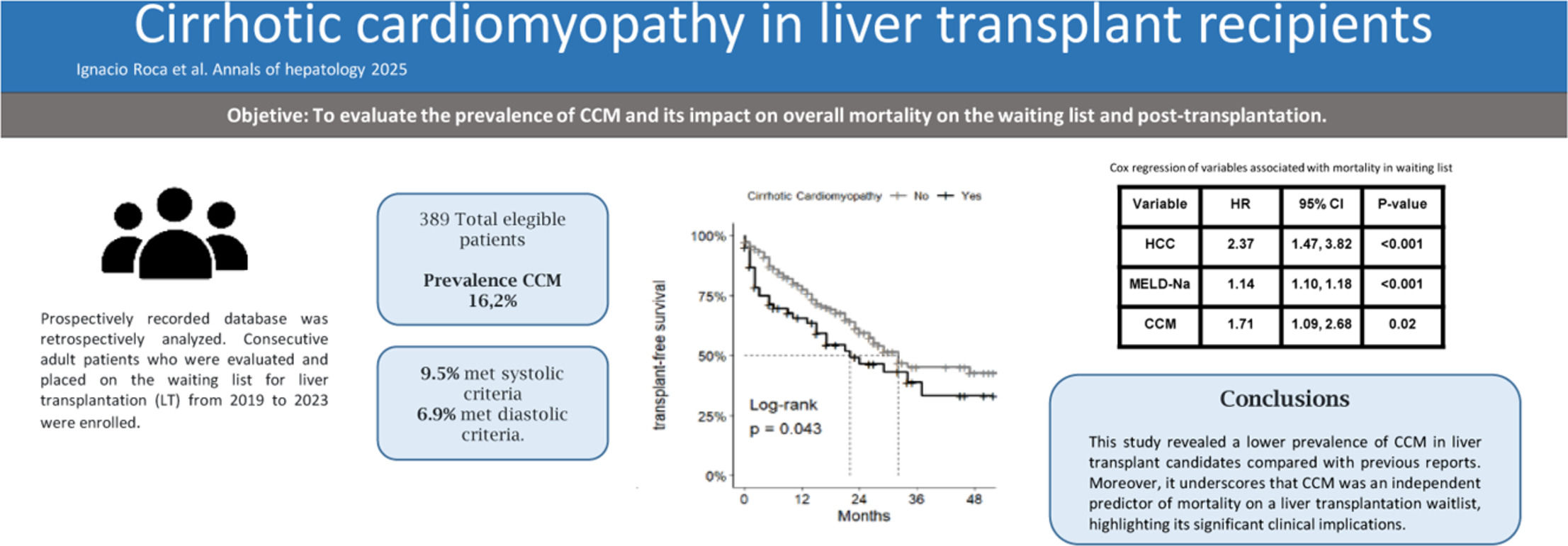

3Results3.1Diagnosis and general characteristicsDuring the study period, 451 echocardiograms of patients undergoing evaluation for liver transplantation were reviewed. Of these, 389 (86.2 %) met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The median age of the patients was 55 years (IQR 46.00, 61.00), and 60.7 % (236) were male.

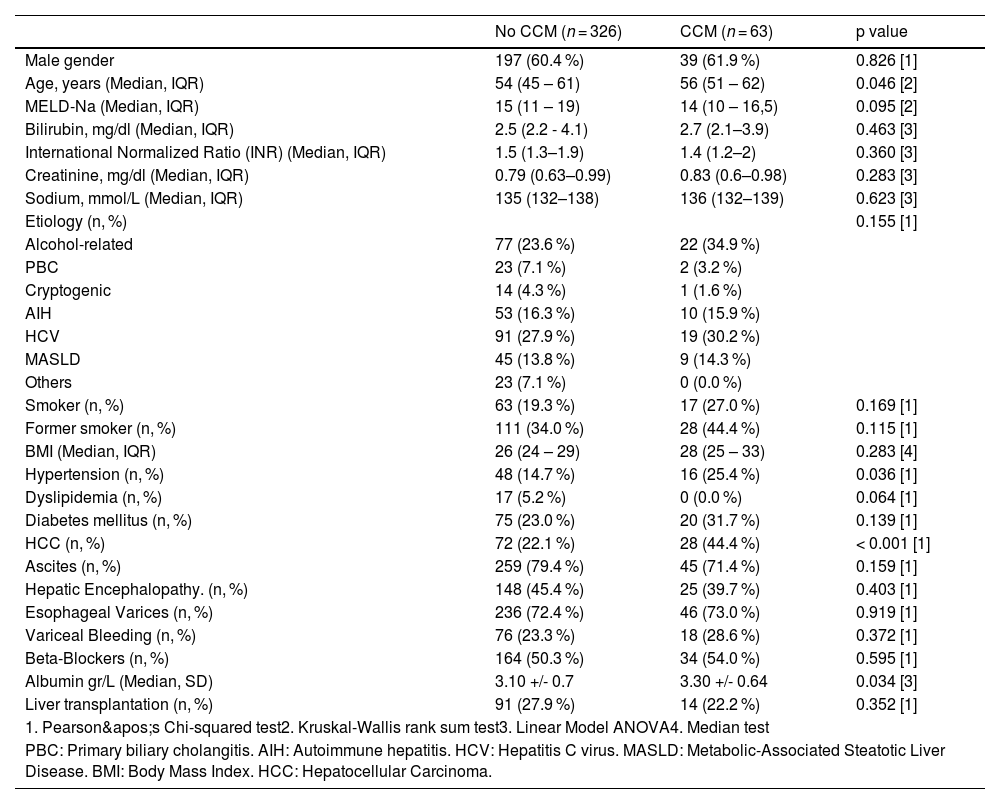

The most common etiology of cirrhosis was hepatitis C virus (HCV) at 28.3 % (110/389), followed by alcohol use at 25.5 % (99/389) and autoimmune hepatitis at 16.2 % (63/389). The baseline characteristics of the cirrhotic patients are detailed in Tables 1 and 2. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy (CCM) was diagnosed in 63 patients, representing 16.2 % of the cohort.

Demographic characteristics.

| No CCM (n = 326) | CCM (n = 63) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 197 (60.4 %) | 39 (61.9 %) | 0.826 [1] |

| Age, years (Median, IQR) | 54 (45 – 61) | 56 (51 – 62) | 0.046 [2] |

| MELD-Na (Median, IQR) | 15 (11 – 19) | 14 (10 – 16,5) | 0.095 [2] |

| Bilirubin, mg/dl (Median, IQR) | 2.5 (2.2 - 4.1) | 2.7 (2.1–3.9) | 0.463 [3] |

| International Normalized Ratio (INR) (Median, IQR) | 1.5 (1.3–1.9) | 1.4 (1.2–2) | 0.360 [3] |

| Creatinine, mg/dl (Median, IQR) | 0.79 (0.63–0.99) | 0.83 (0.6–0.98) | 0.283 [3] |

| Sodium, mmol/L (Median, IQR) | 135 (132–138) | 136 (132–139) | 0.623 [3] |

| Etiology (n, %) | 0.155 [1] | ||

| Alcohol-related | 77 (23.6 %) | 22 (34.9 %) | |

| PBC | 23 (7.1 %) | 2 (3.2 %) | |

| Cryptogenic | 14 (4.3 %) | 1 (1.6 %) | |

| AIH | 53 (16.3 %) | 10 (15.9 %) | |

| HCV | 91 (27.9 %) | 19 (30.2 %) | |

| MASLD | 45 (13.8 %) | 9 (14.3 %) | |

| Others | 23 (7.1 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | |

| Smoker (n, %) | 63 (19.3 %) | 17 (27.0 %) | 0.169 [1] |

| Former smoker (n, %) | 111 (34.0 %) | 28 (44.4 %) | 0.115 [1] |

| BMI (Median, IQR) | 26 (24 – 29) | 28 (25 – 33) | 0.283 [4] |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 48 (14.7 %) | 16 (25.4 %) | 0.036 [1] |

| Dyslipidemia (n, %) | 17 (5.2 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.064 [1] |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 75 (23.0 %) | 20 (31.7 %) | 0.139 [1] |

| HCC (n, %) | 72 (22.1 %) | 28 (44.4 %) | < 0.001 [1] |

| Ascites (n, %) | 259 (79.4 %) | 45 (71.4 %) | 0.159 [1] |

| Hepatic Encephalopathy. (n, %) | 148 (45.4 %) | 25 (39.7 %) | 0.403 [1] |

| Esophageal Varices (n, %) | 236 (72.4 %) | 46 (73.0 %) | 0.919 [1] |

| Variceal Bleeding (n, %) | 76 (23.3 %) | 18 (28.6 %) | 0.372 [1] |

| Beta-Blockers (n, %) | 164 (50.3 %) | 34 (54.0 %) | 0.595 [1] |

| Albumin gr/L (Median, SD) | 3.10 +/- 0.7 | 3.30 +/- 0.64 | 0.034 [3] |

| Liver transplantation (n, %) | 91 (27.9 %) | 14 (22.2 %) | 0.352 [1] |

| 1. Pearson's Chi-squared test2. Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test3. Linear Model ANOVA4. Median test | |||

| PBC: Primary biliary cholangitis. AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis. HCV: Hepatitis C virus. MASLD: Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. BMI: Body Mass Index. HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma. | |||

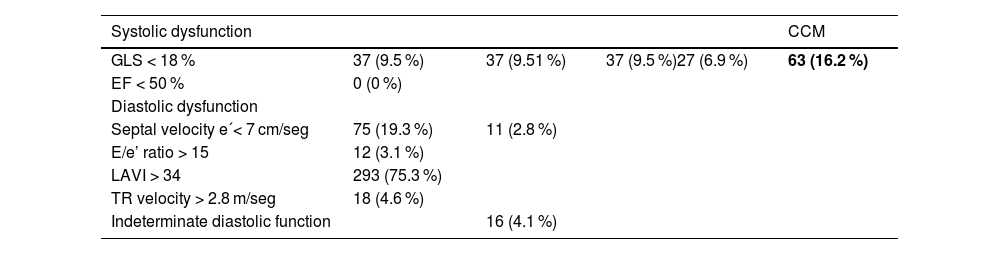

Echocardiographic parameters: Only 1 patient met both systolic and diastolic criteria.

37 (9.51 %) patients met the criteria for systolic dysfunction; none had an LVEF below 50 %, and all diagnoses were based on GLS (see Table 2). The median GLS in the CCM group was 17.7 (IQR 16–17.9) compared to 21.9 (IQR 20–23.9) in the non-CCM group, with a p-value of <0.01. Regarding diastolic dysfunction criteria, 11 patients (2.8 %) met three or more of the criteria proposed by the CCC. LAVI > 34 ml/m² was the most frequently observed diastolic criterion, present in 293 patients (75.2 %), followed by septal e' velocity < 7 cm/sec, present in 75 patients (19.3 %). Among the 62 patients with indeterminate diastolic function (meeting two criteria), 16 (4.1 %) were classified as having diastolic dysfunction after additional tests. Only one patient met the criteria for both systolic and diastolic dysfunction.

3.3Characteristics of patients with CCMA statistically significant age difference was observed in the CCM group, with a median age of 56 years compared to 54 years in the non-CCM group (p = 0.046). This group also had a higher prevalence of arterial hypertension (25.4 % vs. 14.7 %, p = 0.036) and elevated plasma albumin levels (3.30 vs. 3.10, p = 0.034). Additionally, the CCM group exhibited a higher incidence of HCC, with rates double those of the No CCM group (44.4 % vs. 22.1 %, p < 0.001). No significant differences were found between the groups in terms of etiology, MELD-Na score, decompensations, use of beta-blockers (BB), or liver transplantation. Additional evaluated variables are presented in Table 1.

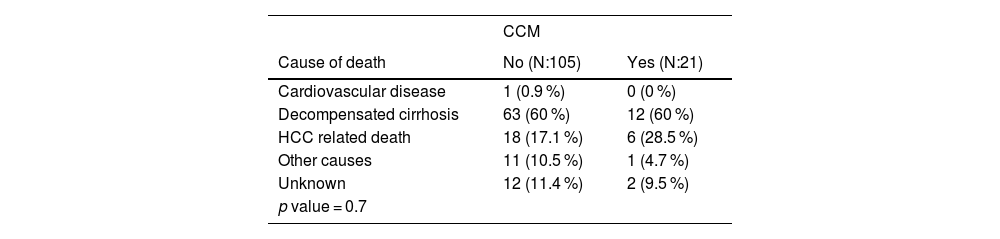

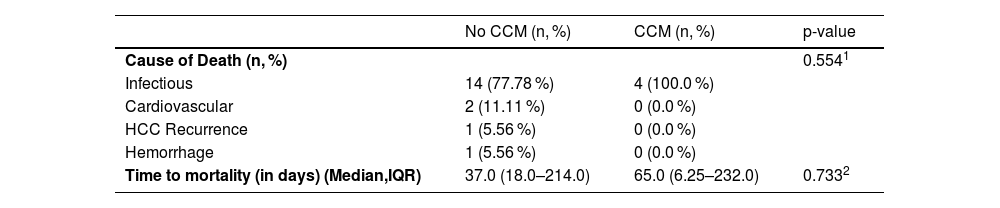

3.4Analysis of causes of mortality126 (32.4 %) patients died while on the waiting list. Table 3 outlines the mortality causes in groups with and without CCM. Cirrhosis decompensation emerged as the predominant cause of death. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups (p-value: 0.7).

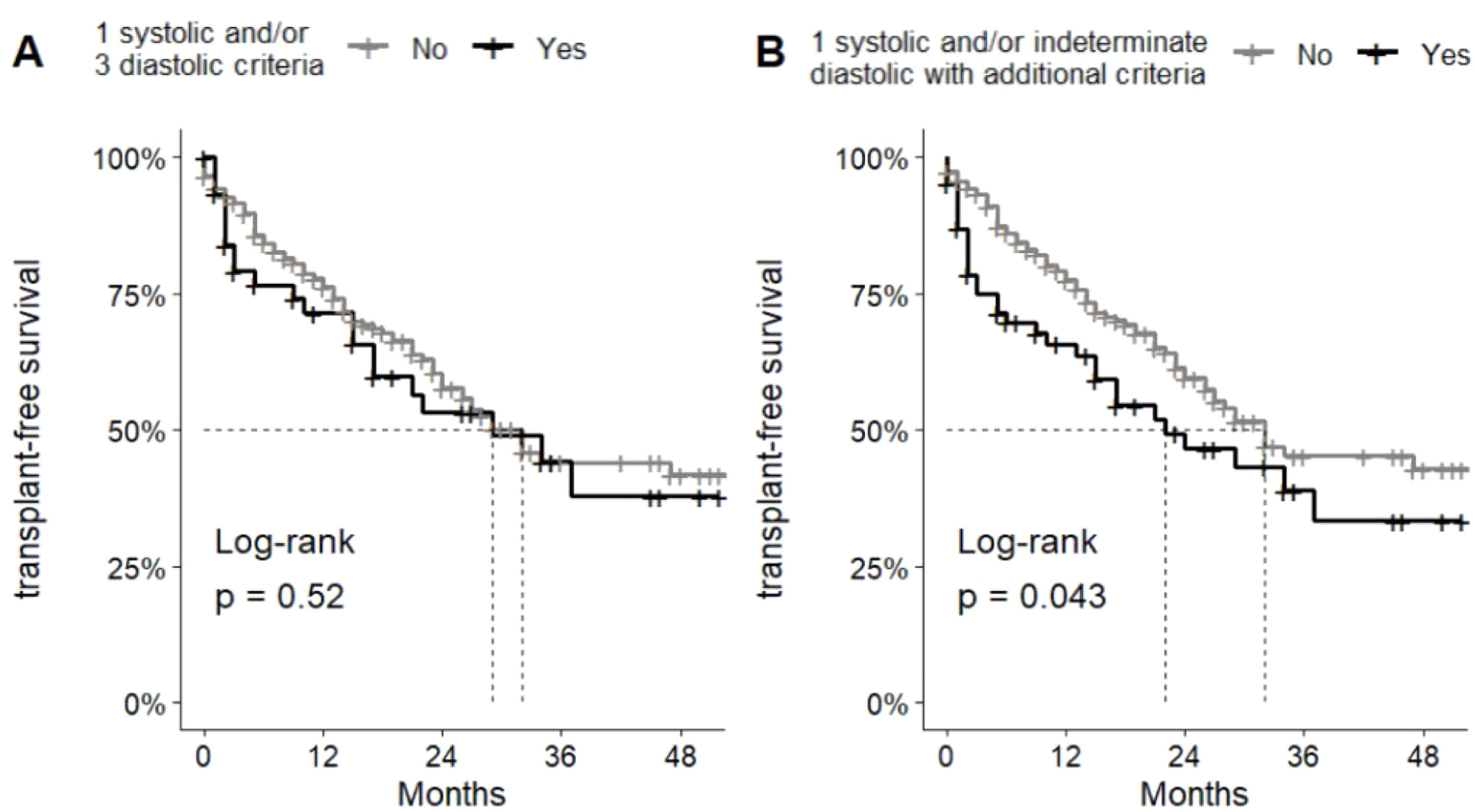

3.5Survival analysis and correlated prognostic factorsIn the survival analysis of patients who met CCM criteria according to the CCC, no differences were observed between the groups (Fig. 1A). However, when analyzed in conjunction with patients with indeterminate diastolic dysfunction who were classified as CCM, the analysis of median transplant-free survival revealed a difference between the non-CCM and CCM groups, with 32 months versus 22 months, respectively, highlighting a statistically significant difference (p00.043) (Fig. 1B).

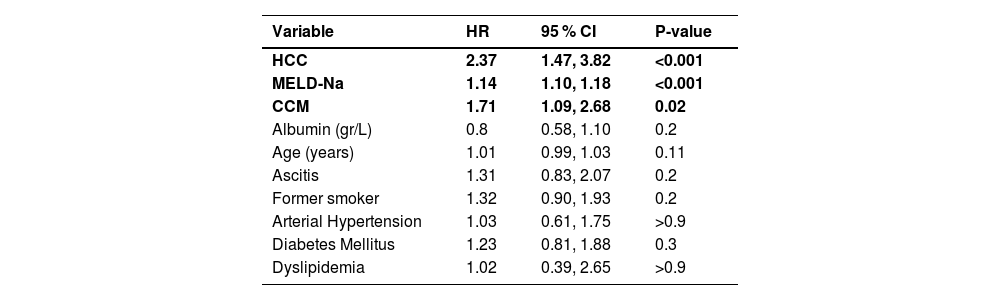

In order to comprehensively evaluate factors associated with mortality while on the waiting list, univariate analysis was initially employed, as delineated in Table 1. Subsequently, a multiple regression analysis was conducted to discern the independent predictors of mortality. This analysis unveiled that CCM (HR 1.71, CI95 % 1.09–2.68, p00.02), MELD-Na score (HR: 1.14, CI95 % 1.10–1.18, p < 0.001), and the presence of HCC (HR 2.37 CI95 % 1.47–3.82, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with mortality on the waiting list (Table 4) (Fig. 2).

Cox regression of variables associated with mortality on the waiting list.

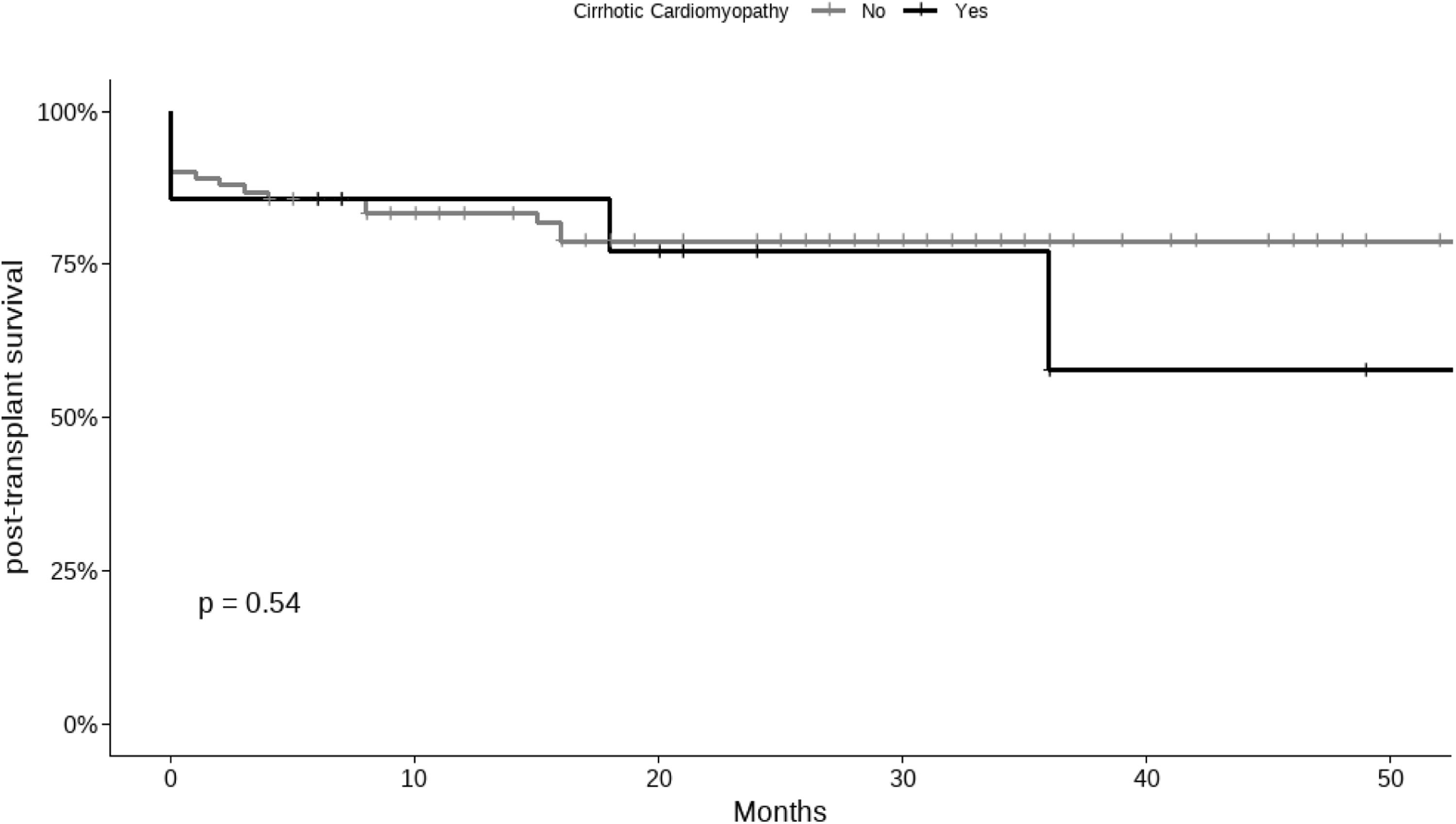

In the comparison of post-transplant causes of death between the CCM and non-CCM groups, no significant differences were found. Infectious causes were the leading cause of death in both groups, with no significant difference in their distribution (see Table 5). The median follow-up post-transplantation was 20 months (IQR 8 - 34), and no significant differences in survival were noted between the groups (Fig. 3).

Postoperative mortality causes following liver transplantation.

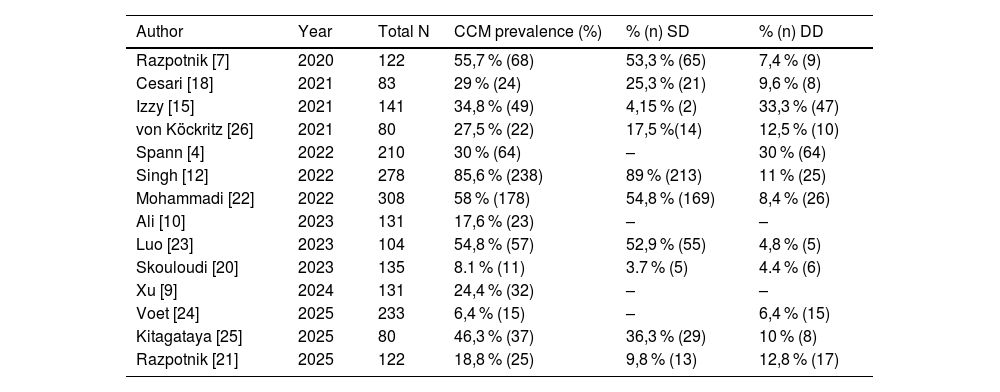

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy (CCM) is defined as cardiac dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis in the absence of prior heart disease [16]. The precise characterization of CCM among patients with ESLD remains challenging. Previous studies estimated the prevalence of CCM to be approximately 6 to 70 % (Table 6); however, these estimations relied on criteria that have since been revised. Recently, Cesari and colleagues reported a prevalence of 29 % using the updated criteria, highlighting a predominance of systolic dysfunction. A similar discrepancy was observed in the study published by Razpotnik and colleagues in 2020 [7], where an error in the original CCC publication led to the use of GLS >22 % as a criterion, resulting in an overestimation of systolic dysfunction prevalence. When corrected, the prevalence in that study would align closer to 19 to 35 % [8–10,18,21].

Prevalence of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy and distribution of systolic dysfunction (SD) and diastolic dysfunction (DD) in recent cohorts assessed using the CCC-2020 diagnostic criteria.

| Author | Year | Total N | CCM prevalence (%) | % (n) SD | % (n) DD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Razpotnik [7] | 2020 | 122 | 55,7 % (68) | 53,3 % (65) | 7,4 % (9) |

| Cesari [18] | 2021 | 83 | 29 % (24) | 25,3 % (21) | 9,6 % (8) |

| Izzy [15] | 2021 | 141 | 34,8 % (49) | 4,15 % (2) | 33,3 % (47) |

| von Köckritz [26] | 2021 | 80 | 27,5 % (22) | 17,5 %(14) | 12,5 % (10) |

| Spann [4] | 2022 | 210 | 30 % (64) | – | 30 % (64) |

| Singh [12] | 2022 | 278 | 85,6 % (238) | 89 % (213) | 11 % (25) |

| Mohammadi [22] | 2022 | 308 | 58 % (178) | 54,8 % (169) | 8,4 % (26) |

| Ali [10] | 2023 | 131 | 17,6 % (23) | – | – |

| Luo [23] | 2023 | 104 | 54,8 % (57) | 52,9 % (55) | 4,8 % (5) |

| Skouloudi [20] | 2023 | 135 | 8.1 % (11) | 3.7 % (5) | 4.4 % (6) |

| Xu [9] | 2024 | 131 | 24,4 % (32) | – | – |

| Voet [24] | 2025 | 233 | 6,4 % (15) | – | 6,4 % (15) |

| Kitagataya [25] | 2025 | 80 | 46,3 % (37) | 36,3 % (29) | 10 % (8) |

| Razpotnik [21] | 2025 | 122 | 18,8 % (25) | 9,8 % (13) | 12,8 % (17) |

In our study, the prevalence of CCM is slightly lower than previously reported in the literature. This difference is likely attributable to the fact that most studies reporting higher prevalence rates included acutely decompensated patients (e.g., ACLF, severe sepsis), where CCM may manifest more clearly. In contrast, the majority of our patients were stable and evaluated in the outpatient setting as part of pretransplant assessments. Additionally, the low prevalence observed, particularly of diastolic dysfunction, could also be influenced by the underrepresentation of patients with MASLD in our cohort. This study contributes to the growing body of evidence by presenting one of the largest series of patients with CCM evaluated using the latest diagnostic criteria established by the CCC in 2020.

Regarding systolic dysfunction, it is important to note that none of the cirrhotic patients in our cohort, spanning different stages of liver disease, presented with a LVEF <50 %. This observation, previously reported in earlier studies [18], underscores the inadequacy of using a low LVEF as a criterion to define cirrhotic cardiomyopathy (CCM), and suggests that its use as a diagnostic criterion should perhaps be reconsidered. While it might be assumed that the absence of patients with an EF < 50 % is due to the fact that this cohort comprises individuals being evaluated for liver transplantation, it is important to emphasize that this evaluation occurred prior to listing, and <10 % of the patients had undergone an echocardiogram before the evaluation.

The recognition of diastolic ventricular dysfunction appears to have a fundamental impact on the development of cirrhosis complications. Ruiz del Arbol and colleagues demonstrated that ventricular dysfunction precedes the development of hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) triggered by bacterial infections [19]. In our study, the prevalence was notably low when solely considering the CCC criteria, but increased to 7 % when incorporating patients with indeterminate diastolic dysfunction who were subsequently classified as having CCM following the additional assessment. This trend aligns with the findings previously observed in the study by Razpotnik et al. [7]. The inclusion of these patients modifies the survival curves on the waiting list between the groups, suggesting that the additional assessment in those patients with indeterminate diastolic dysfunction according to the CCMC criteria could play a significant role in the evaluation of these patients.

Building on these findings, recent studies applying the 2020 CCC criteria have reported a wide range of CCM prevalence and varying associations with waitlist survival. Cesari et al. [18] described a prevalence of 29 % with an increased risk of mortality, while Singh et al. [12] reported a prevalence as high as 85 % and a strong association with waitlist mortality. In contrast, our study found a lower prevalence of 16.2 % but similarly identified CCM as an independent predictor of mortality on the waiting list. These discrepancies may reflect differences in study populations, with prior studies including more acutely decompensated patients, as well as variations in the timing or methodology of echocardiographic assessments. Our findings underscore the need for standardized diagnostic protocols and multicenter studies to better define the prognostic significance of CCM using the new 2020 criteria.

The difference in survival between the groups is noteworthy, despite the absence of differences in MELD-Na score or decompensations, as observed in Table 1. The presence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was significantly higher in the CCM group, with its prevalence being double that of the other group. This contrasts with previous publications where the presence of HCC was reported infrequently. However, upon analyzing mortality causes, the presence of HCC does not differ significantly between both groups and does not appear to be a determining factor in the survival difference between the groups. Given these findings, caution is warranted, and further studies are needed to validate the accuracy of this association.

Regarding post-transplant mortality, the overall survival was close to 80 % at year 5, this percentage may not be accurate because of the small number of transplanted patients included in this study. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of this condition on the post-transplant period. Moreover, an analysis of the causes of death revealed no significant differences between the groups. Notably, the only two cardiovascular-related deaths occurred exclusively in the non-CCM group. Larger studies are required to better assess these findings and determine the true impact of CCM on post-transplant mortality and cardiovascular outcomes.

4.1Limitations and strengthsWe acknowledge that a retrospective study design from a single center might limit the strength of the results; however, the database was prospectively populated, thereby providing increased reliability. Another potential drawback of the study is the involvement of multiple experienced cardiologists in conducting the echocardiograms, which could introduce some inter-observer variability. Additionally, it is important to note that the echocardiograms were performed prior to listing. However, the progression or onset of CCM during the waiting period was not evaluated, and echocardiograms of patients with extended durations on the waiting list were not assessed.

A specific challenge in this study was the classification of patients who met only two of the four 2019 diastolic dysfunction (DD) criteria. According to the current definition, at least three criteria are required for diagnosis, meaning this subgroup does not strictly fulfill the classification for DD. This represents a limitation, as these patients do not fit neatly into existing categories. While they do not meet the criteria for CCM by the 2019 definition, it is also evident that they do not have normal diastolic function. Given this ambiguity, we considered this group as having ‘indeterminate’ DD and conducted additional analyses to better understand their classification. For the purposes of our study, we decided to include this indeterminate group under CCM, as a definitive intermediate category was not available.

The diagnostic criteria for CCM is an evolving concept as new studies appear. Although measurement of LA strain in CCM [20] was published after our study was completed and thus not performed, further research on this technique is needed to determine its usefulness as a diagnostic criterion of CCM.

Among the strengths of this study to be highlighted are the long follow-up and the large sample size of phenotypically well-characterized cirrhotic patients and the use of state-of-the-art echo-Doppler techniques.

5ConclusionsOur study revealed a lower prevalence of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy (CCM) in liver transplant candidates compared to previous reports, likely influenced by the characteristics of our cohort, which primarily included stable outpatients undergoing pretransplant evaluation. Importantly, CCM emerged as an independent predictor of mortality on the waiting list, reinforcing its significant clinical implications. While no differences were observed in post-transplant survival, larger studies are needed to further assess the potential impact of CCM beyond the waiting period. Future research should focus on refining risk stratification for cirrhotic patients with cardiac dysfunction, evaluating its influence on post-transplant cardiovascular outcomes, and identifying potential therapeutic or management strategies to mitigate its impact.

Author contributionsConceptualization: Ignacio Roca (IR), Cecilia Morales (CM), Graciela Reyes (GR), Fernando Cairo (FC); Methodology: IR, CM, GR, Mariela De Santos (MDS), Luciana Meza (LM), Nicolás Domínguez (ND); Validation: GR, CM, Mario Altieri (MA), Hongqun Liu (HL); Investigation/Data collection: CM, MDS, LM, GR, ND, Omar Galdame (OG), Lucía Navarro (LN); Echocardiographic acquisition and analysis: CM, MDS, LM, GR; Data curation: LN, ND, OG, CM, MDS; Formal analysis/Statistics: CM, IR; Resources: FC, MA, HL, SSL; Supervision: FC, MA, HL, SSL, GR; Project administration: IR, FC, GR; Writing – original draft: IR, CM; Writing – review & editing: all authors.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

DisclosuresAll authors declare no conflicts of interest for this study.

Uncited reference[17].

The authors have no competing interests to declare.