Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) is a common cause of end-stage liver diseases (ESLD) and is widely recognized as an indication for liver transplantation (LT) [1–3]. Studies have demonstrated that LT for ALD has comparable outcomes to LT for other causes of ESLD in terms of graft and patient survival [4–6]. However, there is concern that ALD patients may have alcohol relapse after transplantation, which can lead to graft dysfunction, graft failure and poor long-term survival. Historically, transplant programs have required candidates to demonstrate six months of alcohol abstinence before consideration for LT. This "six-month rule" was established with two intentions: to allow for potential recovery through medical management and to predict post-transplant sobriety. However, mounting evidence challenges the validity of this arbitrary timeframe as a reliable predictor of post-transplant outcomes [7]. Recent studies demonstrate that adherence to the six-month rule does not necessarily correlate with superior patient survival, allograft survival, or relapse-free survival [8]. In fact, other studies have found that the duration of pre-transplant abstinence does not reliably predict post-transplant alcohol relapse [7]. This raises significant concerns about potentially excluding candidates from life-saving transplantation based on an unvalidated criterion. The constraint is particularly problematic for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis or advanced decompensation who may not survive the six-month waiting period [3]. Recent studies increasingly suggest that psychosocial factors — including psychiatric comorbidities, compliance with medical advice and family support systems, may be more predictive of post-transplant relapse than abstinence duration alone [3,9,10].

Despite the growing utilization of both deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) and living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) for ALD patients, comparative data examining outcomes between these two approaches specifically in the ALD population remains limited [11]. Thus, this study aimed to compare the outcomes of ALD patients after LDLT and DDLT, and to analyze predictors for post-transplant relapse and graft survival.

2Patients and Methods2.1Study designThis was a retrospective study from Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong. All data were retrieved from a prospectively collected database. All ALD patients referred to the unit from 1st January 2008 to 31st December 2020 were included. Patients who were listed with a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) exception or those with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were excluded from the study. The analysis was performed on an intention-to-treat (ITT) and LT-type basis. Patients who had an eligible live donor were classified as intended for LDLT i.e., ITT-LDLT. Patients who did not have a live donor or refused LDLT were classified as intended for DDLT i.e., ITT-DDLT. With ITT analysis, patient survival was measured from the time of LT evaluation to the study endpoint. It allowed us to study the risk of waitlist dropout i.e., delist or death in the cohort. Patients who were deemed ineligible for LT due to medical, psychosocial, or other contraindications, such as recovery or refusal, constituted the control group.

2.2Study objectivesThe primary objective of this study was to compare the graft survival rates of ALD patients who underwent DDLT and LDLT. Secondary objectives included comparing waitlist and perioperative outcomes after DDLT and LDLT, examining patterns of alcohol relapse after LT, and assessing the impact of relapse on graft survival. We also aimed to analyze predictors for graft survival and alcohol relapse after LT.

2.3Patient characteristicsIn our study, psychiatric disorders were classified according to the major diagnostic categories outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-IV) [12]. Patients’ alcohol consumption was measured as the weekly alcohol intake, standardized using the World Health Organization alcohol units [13], and quantified at the time of LT evaluation. Alcohol dependence was diagnosed clinically, primarily based on the criteria described in DSM-IV [12]. Medical non-compliance was defined as poor adherence to prescribed medications or missed clinical visits after transplantation, as assessed by physicians.

2.4Pre-transplant assessmentAt our center, ALD patients intended for DDLT were required to complete a 6-month period of alcohol abstinence prior to being listed for LT. In contrast, LDLT patients were permitted to proceed without meeting the 6-month abstinence requirement, provided they met the following criteria: 1) understand the harmful effects of alcohol, 2) have a commitment to lifelong abstinence after LT, 3) demonstrate acceptance-based coping instead of avoidance or disengagement strategies, 4) have social support, 5) have no other substance abuse, and 6) have no poorly controlled psychiatric condition. The patients, together with their family members and close friends, were interviewed by clinical psychologists specializing in LT services, both before and after the procedure. The CAGE questionnaire was administered to every patient as part of the psychosocial assessment.

2.5Post-transplant alcohol relapse and immunosuppressionAlcohol relapse was defined as any alcohol consumption after LT. Sustained alcohol use was defined as the patient’s inability to regain sobriety up to the most recent follow-up. Drinking habits were further categorized according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [14] into harmful drinking, which included binge drinking (≥ 5 U/occasion for males, ≥ 4 U/occasion for females) or frequent alcohol use (≥ 4 days/week). Alcohol abstinence was assessed through patient interviews during clinic follow-ups. For systemic surveillance, once patients were clinically stable after transplant, they were followed up every 3 months jointly by a transplant surgeon and hepatologist. At each visit, serum gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and selective blood ethanol levels were checked, alongside detailed history-taking with specific inquiry regarding any alcohol relapse. The diagnosis of alcohol relapse was based on self-reports from patients, reports from family members and relevant biochemical tests. Post-transplant immunosuppression regimen at our center was included in the supplementary material.

2.6Statistical analysisPre-transplant analyses comparing baseline characteristics of patients and potential donors were conducted based on ITT principle, starting from the time of LT evaluation. This meant all ALD patients referred to our center for LT were included in the analysis, regardless of whether they eventually underwent LT. Post-transplant analyses comparing patient outcomes were conducted based on the type of LT (LDLT or DDLT), starting from the time of LT.

Continuous variables in the study were reported as median with range and categorical data as number and percentage. Comparisons between groups were made using Pearson’s Chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, the Mann-Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis test where appropriate. Patient and graft survival rates were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. ITT survival was defined as patient survival from LT evaluation to death of any cause, whereas post-transplant survival was defined as patient survival from transplant to death of any cause. Cox regression analyses were used to identify variables that predicted graft survival and alcohol relapse. Waitlist futility was defined as waitlist death or delisting due to being too sick for LT. A competing risk analysis of waitlist futility was done between ITT-LDLT and ITT-DDLT groups, with LT as a competing event.

Univariable analyses were performed using factors related to patients’ and donors’ demographics, biochemical data, and postoperative events. Factors that had a significance level of p < 0.10 in the univariable analysis were included in the multivariable analyses. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 and all tests performed were two-tailed. All analyses were done using SPSS version 28.0.

2.7Ethical considerationsThis retrospective study did not incur any clinical intervention for patients. The patient data were de-identified and anonymous. During the study, the source data was kept in a secure place at the study site. There was no elevated risk exposed to the patients in this study. Donor consent procedures met local regulations. Pre- and post-operative clinical psychologist follow-ups were offered for both donors and recipients. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (UW 24-165).

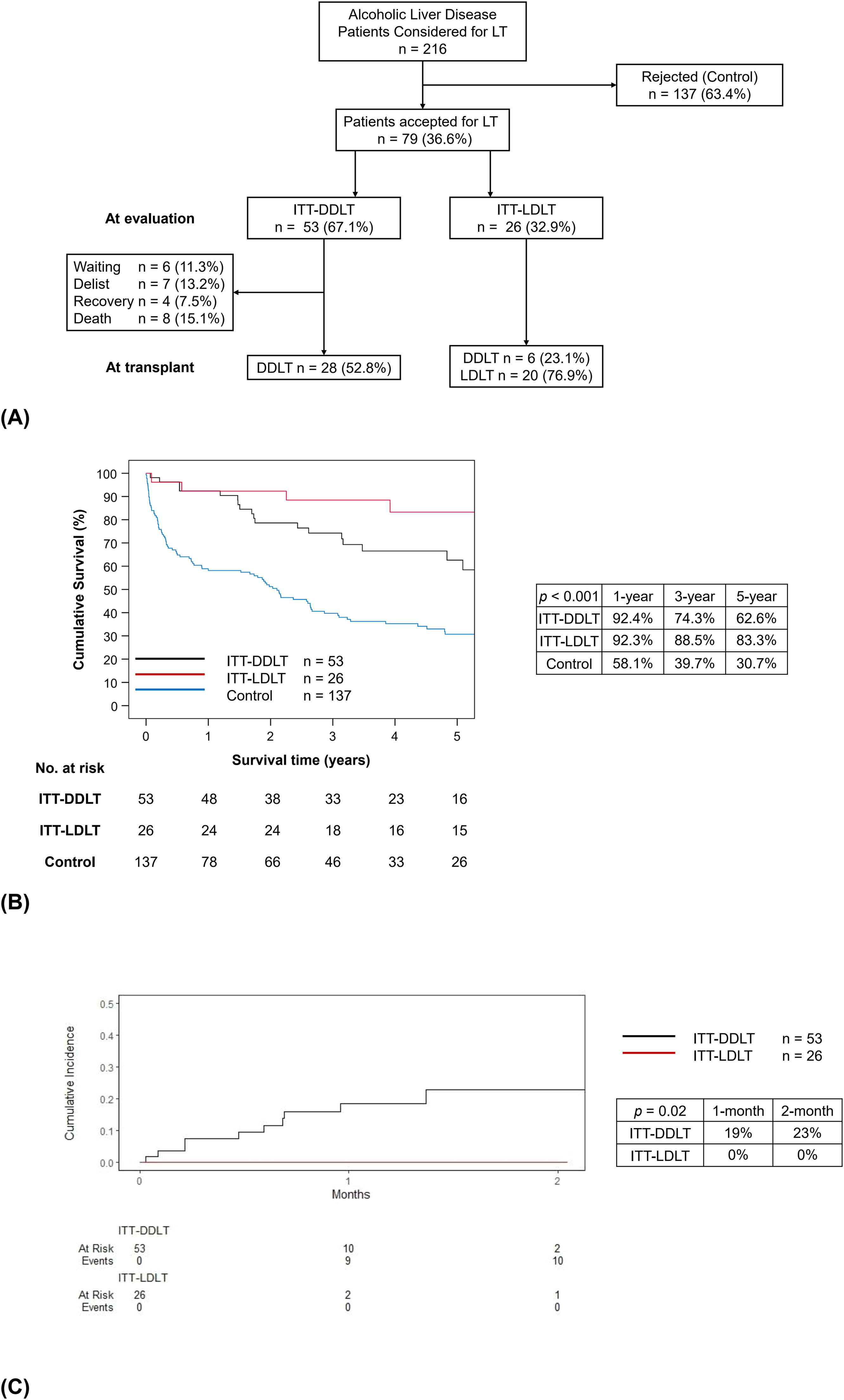

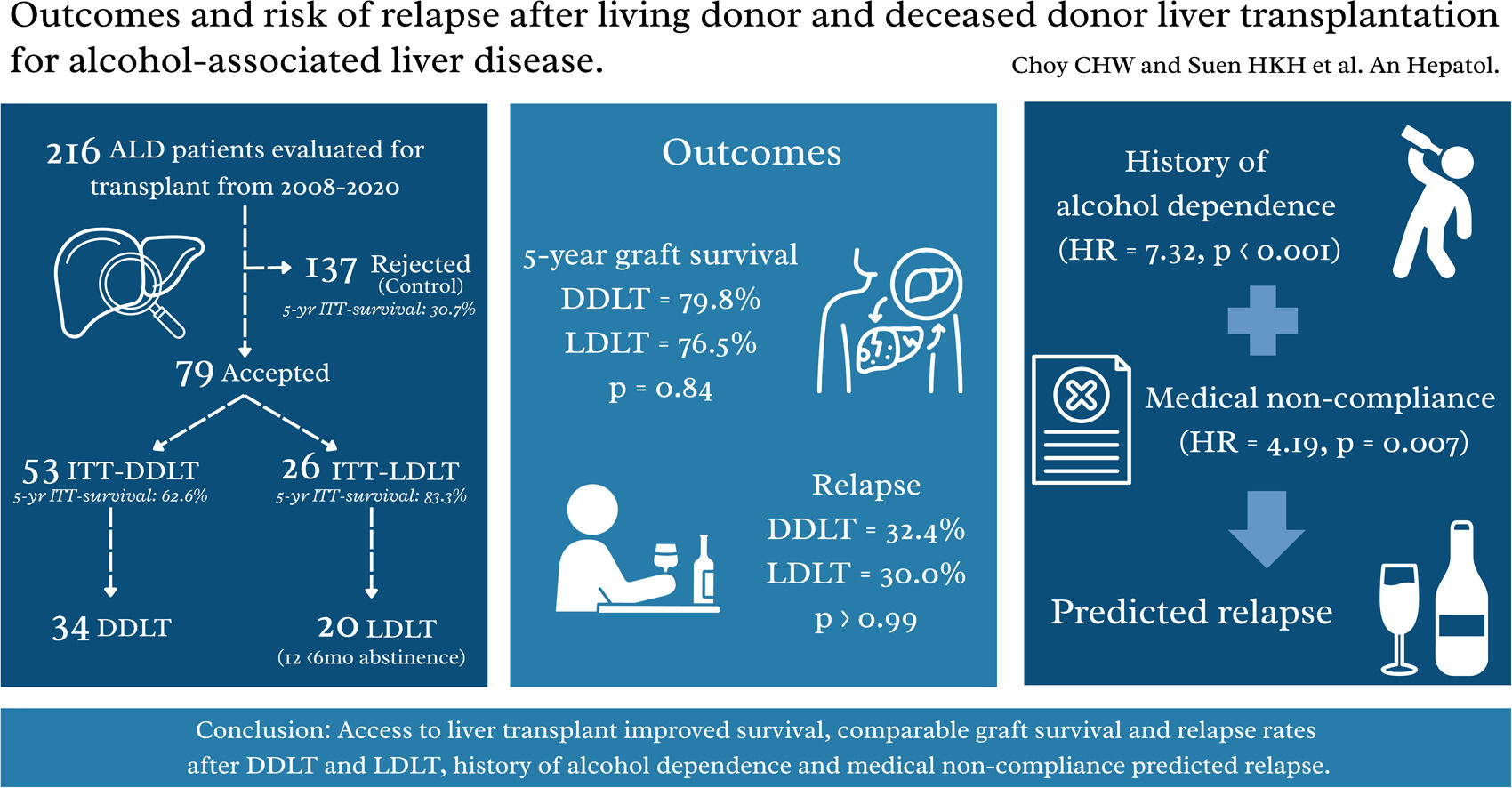

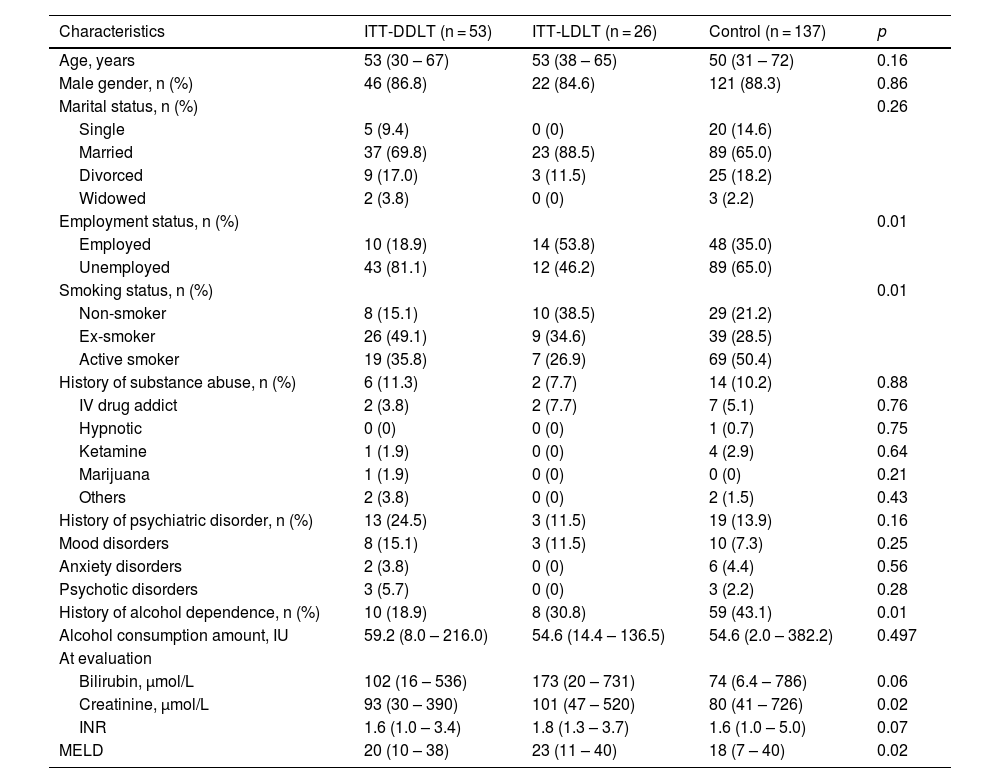

3Results3.1Study populationDuring the study period, 216 patients with ALD were referred for LT. Among them, 79 (36.6%) were accepted for listing. The main reasons for non-acceptance to LT included medical comorbidities (33.6%), incomplete alcohol abstinence (31.4%) and recovery (20.4%). The waitlist outcomes were shown in Figure 1A. Among the ITT-DDLT group, 7 patients were delisted due to medical comorbidities in 4, ongoing alcohol use, LT overseas and patient refusal, respectively. Most patients were male in the ITT-DDLT group (86.8%), the ITT-LDLT group (84.6%) and the control group (88.3%, p = 0.86). Approximately 10% of patients had a history of substance abuse in all groups (p = 0.88), while around one-tenth to a quarter of patients had a history of psychiatric disorder (p = 0.16). The proportion of patients with a history of alcohol dependence was the highest in the control group (43.1%), compared to the ITT-DDLT group (18.9%) and the ITT-LDLT group (30.8%) (p = 0.01). The median MELD score was the highest in the ITT-LDLT group, followed by the ITT-DDLT group and the control group (23 vs. 20 vs. 18, p = 0.02) (Table 1). The ITT-LDLT group had better 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates (92.3%, 88.5% and 83.3%, respectively) than the ITT-DDLT group (92.4%, 74.3% and 62.6%, respectively) (p = 0.04). The control group had the worst ITT-survivals of 58.1%, 39.7% and 30.7% at 1-, 3- and 5-year respectively (p < 0.001) (Figure 1B). Competing risk analysis showed that the availability of a live donor and early access to LT could eliminate waitlist futility (Figure 1C). A per-protocol ITT analysis was done including only the listed patients and the results showed that the ITT-LDLT group had superior survival up to 5 years (100% vs. 62.6%, p = 0.01), which was consistent with the primary analysis (Supplementary Figure 1).

(A) Flow chart of all patients with alcohol-associated liver disease considered for liver transplantation, (B) Intention-to-treat survival for all patients from the time of evaluation, (C) Competing risk analysis of waitlist futility. Patients were stratified into control and intention-to-treat groups as at evaluation. Waitlist outcomes and number of patients proceeding to each type of liver transplantation were documented. Data presented as number (percentage). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed and showed superior intention-to-treat survival for ITT-LDLT patients (red line), compared to ITT-DDLT (black line) and control (blue line); p < 0.001. Competing risk analysis showed higher cumulative incidence of waitlist futility for ITT-DDLT patients (black line) compared to none in ITT-LDLT patients (red line); p = 0.02.

Characteristics of all patients at evaluation.

MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

Continuous variables are expressed as median (range). Categorical variables are expressed as the number of patients (percentage).

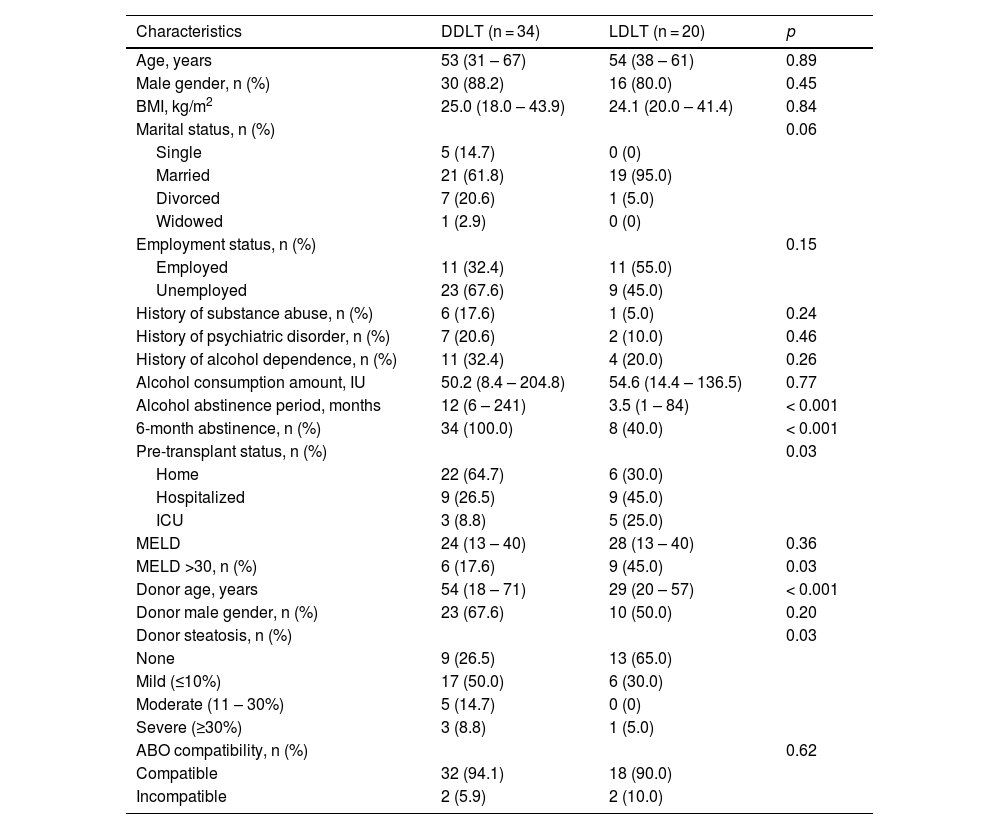

In the present study, 34 patients underwent DDLT and 20 had LDLT. We were unable to show a difference in pre-transplant alcohol consumption per week between the DDLT and LDLT groups (50.2 IU vs. 54.6 IU, p = 0.77). However, the median duration of alcohol abstinence was longer in the DDLT group (12 months vs. 3.5 months, p < 0.001). In the DDLT group, all patients had a minimum of 6 months of alcohol abstinence prior to transplantation. On the other hand, only 8 (40.0%) in the LDLT group had abstained for 6 months before transplantation, and 2 of 12 (16.7%) were transplanted for acute alcohol-associated hepatitis without a prior diagnosis of ALD. More DDLT patients were at home before transplantation compared to LDLT patients (64.7% vs. 30.0%, p = 0.03). The median MELD scores were similar (24 vs. 28, p = 0.36), though the proportion of patients with high MELD >30 was higher in the LDLT group (17.6% vs. 45.0%, p = 0.03). The overall waiting time for LT was 4.5 months, and the waiting time for DDLT was longer when compared to LDLT (8.2 months vs. 0.8 months, p < 0.001). Live donors were younger compared to deceased donors (29 years vs. 54 years, p < 0.001). There was a higher proportion of steatosis in deceased donors than live donors (73.5% vs. 35.0%, p = 0.03). Overall, the characteristics were otherwise similar between the two groups (Table 2).

Characteristics of recipients and donors at the time of liver transplant.

BMI, body mass index; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

Continuous variable is expressed as median (range). Categorical variables are expressed as the number of patients (percentage).

The operative outcomes of all recipients and donors are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. All patients who underwent DDLT received whole liver grafts from brain dead donors. There were two hospital mortalities after LDLT. There was one Clavien-Dindo grade 2 complication but no severe complications (≥ Clavien-Dindo 3a) [15] or hospital mortality in the live donors.

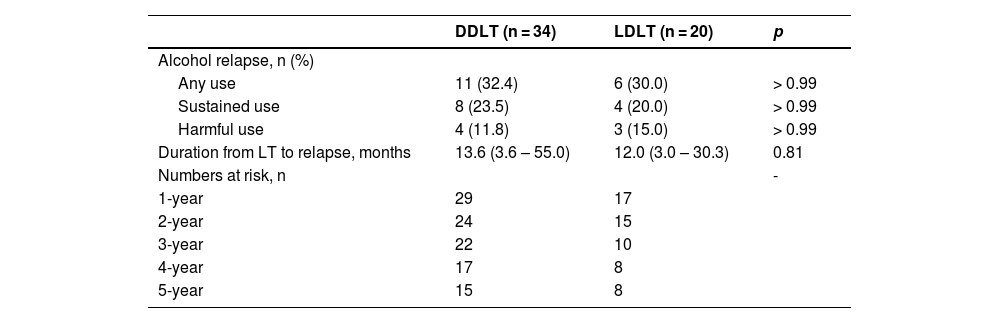

3.3Alcohol relapse patternsWe were unable to show that there was a significant difference in alcohol relapse rates between patients who fulfilled the 6-month abstinence rule and those who did not (31.0% vs. 33.3%, p > 0.99). Seventeen (31.5%) patients relapsed to alcohol use after transplant, with 12 (22.2%) sustained users and 7 (13.0%) showing harmful use. Table 3 compared the alcohol relapse patterns between DDLT and LDLT patients. The risk of alcohol recidivism was similar between the 2 groups (32.4% vs. 30.0%, p > 0.99). The median duration from LT to the first alcohol relapse was 13.6 months and 12 months in DDLT and LDLT patients respectively (p = 0.81). Among the 17 patients who experienced a relapse, 11 (64.7%) had graft dysfunction, of which 9 (81.8%) were related to alcohol use. The 2 cases of non-alcohol related graft dysfunctions were due to poor compliance with immunosuppression.

Patterns of alcohol relapse in recipients.

Continuous variables are expressed as median (range).

Categorical variables are expressed as the number of patients (percentage).

Sustained use is defined as the inability to regain sobriety up to the most recent follow-up.

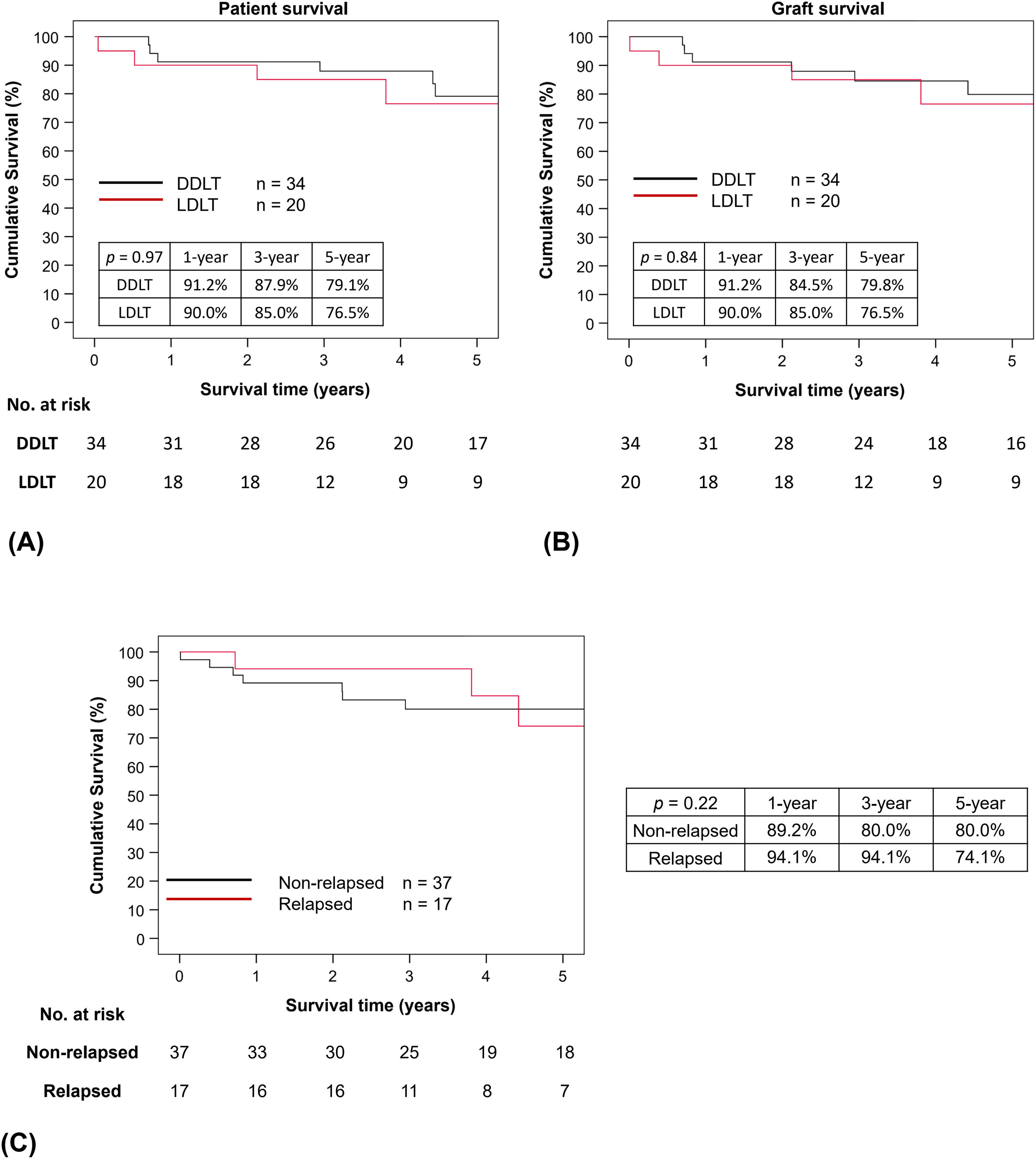

For the whole cohort, the 1-, 3- and 5-year patient and graft survival rates were 90.7%, 86.5% and 78.0%, and 90.7%, 84.5% and 78.6%, respectively. The 1-, 3- and 5-year patient survival rates after DDLT were 91.2%, 87.9% and 79.1%, respectively, and they were similar to the LDLT group (90.0%, 85.0% and 76.5%, respectively, p = 0.97). Similarly, graft survival rates at 1, 3 and 5 years after DDLT (91.2%, 84.5% and 79.8%, respectively) and LDLT (90.0%, 85.0% and 76.5%, respectively, p = 0.84) were comparable (Figures 2A and 2B). The median survival after transplant was 49.9 (0.1 – 164.6) months and it was similar between the DDLT and LDLT groups [54.8 (8.4 – 164.6) months vs. 44.5 (0.1 – 154.6) months respectively, p = 0.68]. Till the latest follow-up, 14 patients died after transplant; 8 (21.6%) were among the 37 non-relapsed patients and 6 (35.3%) in the 17 relapsed patients (p = 0.29). Of the 6 who relapsed, 2 (33.3%) were alcohol-related mortalities. Malignancies were the primary cause of mortality in the remaining patients, followed by renal failure.

(A) Patient and (B) graft survival by type of liver transplantation, and (C) Graft survival by any relapse. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were used to analyze patient and graft survivals. Both were similar between DDLT (black line) and LDLT (red line); p = 0.97 and p = 0.84 for patient and graft survival, respectively. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was also conducted to compare survival between patients who relapsed after liver transplantation (red line) and those who remained abstinent (black line). Survival rates were similar; p = 0.22.

Graft survival rates between relapsed and non-relapsed patients were evaluated in Figure 2C and we were unable to show statistically significant difference between the 2 groups (p = 0.22). In the non-relapsed group, the graft survival rates at 1-, 3- and 5-year were 89.2%, 80.0% and 80.0%, respectively. Whereas in the relapsed group, the graft survival rates were 94.1%, 94.1% and 74.1%, respectively. A post-hoc analysis of graft survival comparing relapsed and non-relapsed patients after excluding patients who had early mortality after LT (i.e. within 90 days after LT) showed similar results to the primary analysis (Supplementary Figure 2). A sensitivity analysis was carried out to compare eras and learning effect by dividing our cohort into Era 1 (2008 – 2014) and Era 2 (2015- 2020). Our results showed there was no difference in patient and graft survival rates between the 2 eras (Supplementary Figure 3A and 3B).

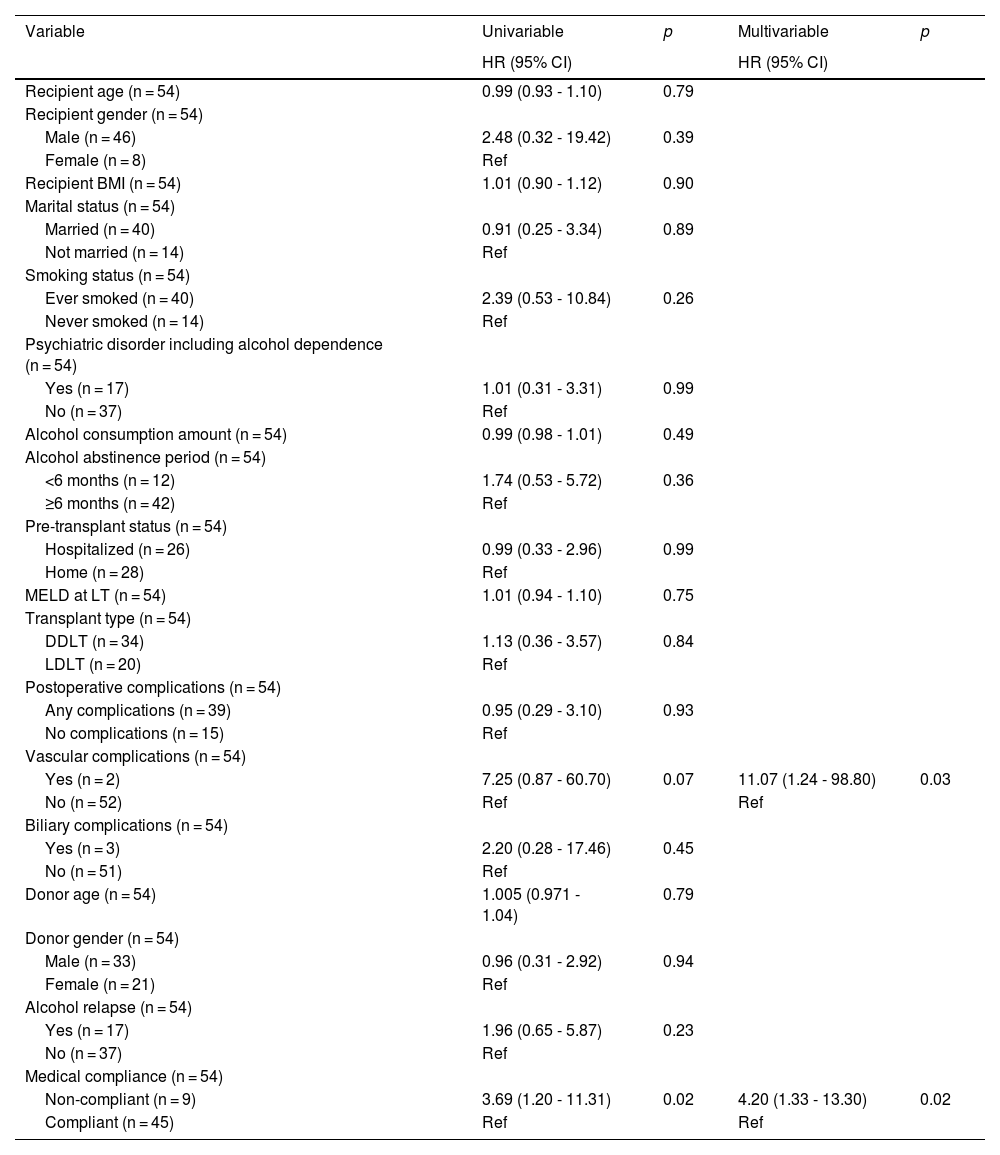

3.5Prognostic factors affecting graft survivalTable 4 showed the univariable and multivariable analyses of prognostic factors that affect graft survival. In the multivariable analysis, post-transplant vascular complications [HR = 11.07 (1.24 – 98.80), p = 0.03] and medical non-compliance [HR = 4.20 (1.33 – 13.30), p = 0.02] were independent factors associated with poor graft survival. History of psychiatric disorder including alcohol dependence [HR = 1.01 (0.31 – 3.31), p = 0.99], alcohol consumption amount [HR = 0.99 (0.98 – 1.01), p = 0.49], <6-month pre-transplant alcohol abstinence [HR = 1.74 (0.53 – 5.72), p = 0.36] and post-transplant alcohol relapse [HR = 1.96 (0.65 – 5.87), p = 0.23] had no significant impact on graft survival.

Univariable and multivariable analyses of prognostic factors affecting graft survival.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

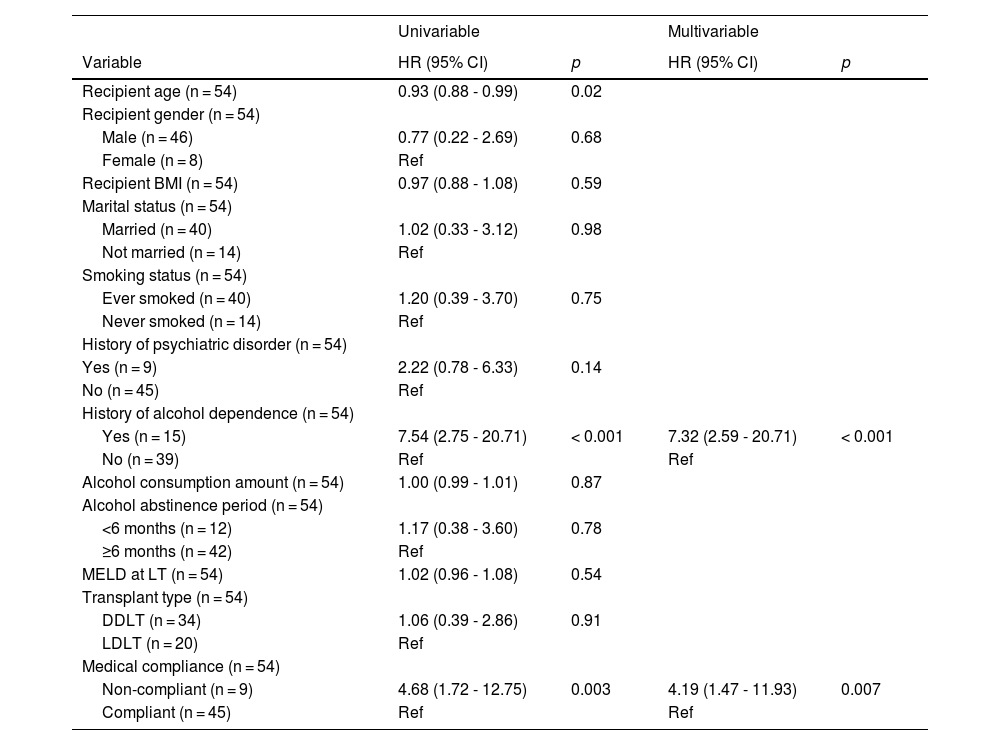

Table 5 showed the univariable and multivariable analyses of predictors of alcohol relapse. In the multivariable analysis, the independent predictors of relapse were a history of alcohol dependence [HR = 7.32 (2.59 – 20.71), p < 0.001] and medical non-compliance [HR = 4.19 (1.47 - 11.93), p = 0.007].

Univariable and multivariable analyses of predictors of alcohol relapse.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

This study is the first to evaluate outcomes of ALD patients using an ITT and competing risk analysis, incorporating control patients to assess waitlist outcomes. Our findings highlighted that early access to LT, particularly through LDLT, provided significant survival benefits for ALD patients and eliminated waitlist futility. Notably, 60% of LDLT recipients did not meet the conventional six-month abstinence rule but were fast tracked based on favorable psychological assessments, without compromising long-term survival or increasing alcohol relapse rates.

Consistent with previous studies [2,3], control patients had poor survival outcomes with a 5-year survival rate of only 30.7%. This underscored the urgency of LT in advanced ALD and highlighted the limitations of the six-month abstinence rule, as many ALD patients may not survive this waiting period. Given that listing for LT is a highly selective process, the relatively high proportion of control patients with a history of alcohol dependence and incomplete abstinence explained why one-third of the control patients were declined for LT. ITT-LDLT patients demonstrated superior 5-year survival (83.3%) compared to ITT-DDLT patients (62.6%), possibly due to reduced waitlist mortality facilitated by the availability of a living donor. In contrast, ITT-DDLT patients faced significant risk of futile waitlist outcomes, with 28.3% either delisted or died while awaiting LT.

Patients in the LDLT group were more critically ill, with higher MELD scores and greater need for intensive care prior to LT. Despite this, their post-transplant outcomes, including graft survival and complication rates, were comparable to those of DDLT recipients. It is important to note that 60% of patients in the LDLT group did not meet the 6-month abstinence criteria and thus, traditionally considered contraindicated for LT. Importantly, our study was not able to demonstrate that there was a significant difference in alcohol relapse rates between LDLT and DDLT groups, with an overall relapse rate of 31.5%. Predictors of relapse included psychiatric disorders and medical non-compliance. These factors should guide patient selection and management rather than rigid adherence to a 6-month abstinence period.

The absence of significant difference in relapse rates between LDLT and DDLT challenges assumptions that living donation from family members might reduce relapse risk [7] and mitigate the need for a mandatory abstinence period. Nonetheless, alcohol relapse following LDLT carries substantial psychosocial implications for both recipients and donors, necessitating comprehensive psychological support for all involved parties. Furthermore, the long-term outcomes of living donors, particularly regarding psychological well-being, warrant careful consideration. Our center provides lifetime follow-up for all living donors, and it is crucial to offer proactive psychological support to donors, especially when recipients experience alcohol relapse or graft failure. While some studies [16,17] have suggested that younger recipient age predicted relapse, our findings only showed a weak association. Other studies [16–19] have suggested that being unmarried, smoking, having previous repeated alcohol-treatment failures, substance abuse, and a lower MELD score at listing were predictive of relapse, which were not demonstrated in our cohort. Our study only found a history of psychiatric disorder and medical non-compliance to be strong predictors for relapse, consistent with other studies [16,18,20]. Regarding pre-LT abstinence period, while some studies [6,18–20] demonstrated that <6-month abstinence was a predictor, our study was unable to show an association, aligning with other findings [16,17] that the duration of pre-transplant abstinence might not be a reliable indicator. These findings highlight the need for better multidisciplinary evaluation and treatment of underlying psychiatric disorders, especially alcohol dependence, before and after LT. Our center is actively exploring the utilization of additional validated tools, for example Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplant (SIPAT) and Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), to enhance psychosocial assessments for future candidates [21,22].

In our study, the overall alcohol relapse rate was 31.5%, slightly higher than some published data [1–4,6,7,17,23–28]. The median time from LT to relapse was approximately 1 year in both groups, possibly reflecting when patients regained physical strength and were reintegrated into the community. Alcohol relapses were largely detected based on self-reporting or from random serum ethanol testing when the patients developed graft dysfunction. A standardized screening and detection for alcohol use with better biomarkers such as urine ethyl glucuronide and serum phosphatidylethanol could improve early detection and intervention for relapse [29].

Medical non-compliance is well-documented to be associated with underlying alcohol dependence [30,31] and was shown in our study as a predictor of poor graft survival and alcohol relapse. However, substantial interactions likely exist between medical non-compliance and alcohol abstinence. Established patterns of medical non-compliance may increase the risk of alcohol relapse, whereas resumption of alcohol use following LT constitutes, by definition, a major form of non-compliance with medical advice. A structured psychological follow-up after LT involving the patient and their family could be helpful in reducing the risk of alcohol relapse [32,33].

The graft survival of relapsed and non-relapsed ALD patients was comparable in our study. Only a small number of relapsed patients died from alcohol-related graft failure, possibly due to prompt medical and psychological intervention once alcohol relapse was detected at our center. This also explained why sustained alcohol use was only observed in a minority of patients. The main reasons for non-alcohol-related deaths were malignancies and renal failure, consistent with previous findings [5,34] that de novo malignancy was the leading cause of long-term mortality in ALD patients.

Similar to other LDLT programs, ALD patients at our center were eligible for LDLT even if they had not completed the six-month abstinence period, provided they received a favorable psychological evaluation. In contrast, DDLT candidates had to fulfill the six-month abstinence rule to be waitlisted. Deceased donor organs are a scarce public resource, particularly in Asia, where extreme organ shortages demand equitable allocation. The six-month abstinence policy is traditionally used to assess commitment to sobriety and allow for potential liver recovery, possibly avoiding the need for LT. However, this requirement has been criticized as arbitrary, rooted in perceptions of ALD as self-inflicted, and potentially delaying life-saving treatment. Many ALD patients with severe disease may not survive the six-month waiting period if denied access to LT.

Our study had several limitations, including its retrospective design, small sample size, dependence on self-reported alcohol use and medical compliance, and selective serum ethanol testing. The small sample size may limit statistical power and external validity and may result in residual confounding of disease severity despite multivariable adjustment. In addition, practice at our center may not be generalizable to other programs; consequently, comparison between LDLT and DDLT should be interpreted cautiously. Most patients were unable to accurately recall the precise timing of their initial return to alcohol use. Therefore, the timing of the first clinically documented relapse may not reflect the exact onset of alcohol relapse. Due to institutional resource constraints, phosphatidylethanol (PEth) testing was unavailable during the study period. However, implementation of PEth testing is currently being pursued at our center. Despite accumulating evidence suggesting that a rigid six-month abstinence period is an unreliable predictor of post-transplantation outcomes or relapse, many transplant centers continue to observe this protocol. Future prospective studies with larger cohorts and more comprehensive alcohol use monitoring may further validate our findings.

5ConclusionsITT-LDLT offers substantial survival advantages for ALD patients by reducing waitlist mortality without compromising post-transplant outcomes. A rigid six-month abstinence rule may unnecessarily delay life-saving treatment and was not associated with better graft survival or a lower relapse rate in this cohort; instead, psychosocial assessments should guide candidate selection. Future studies should focus on refining psychosocial evaluation tools and improving post-transplant monitoring strategies to optimize outcomes in this complex patient population.

FundingThis study was funded by General Research Fund [GRF17115618] and Theme-based Research Scheme [T12-703-19R] of the Research Grants Council, Hong Kong.

AuthorshipCHW Choy, HKH Suen and TCL Wong were responsible for drafting of manuscript, conception, design and acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data. MY Chan, KP Au, JWC Dai, JYY Fung, TT Cheung and ACY Chan have all made significant contributions to conception, design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. All authors have participated in drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors have given final approval for the version to be published.

None.