Cirrhosis is the end stage for many chronic liver diseases and a leading cause of disease-related morbidity and mortality [1,2]. The onset of a decompensating event (e.g., ascites, hepatic encephalopathy [HE], or variceal bleeding) is a watershed in the natural history of cirrhosis, since the median survival is reduced from >12 years to approximately 2 years [3], with a deep impact on healthcare systems due to high hospitalization rates [4]. An epidemiological analysis in Italy demonstrated that the costs associated with cirrhosis-related hospitalizations were approximately 30 % higher than those for hospitalizations due to heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [5]. Treatment of decompensated cirrhosis is limited to the management of the single complications [1,6,7]. Thus, liver transplantation is, in most cases, the only definitive cure for decompensated cirrhosis; however, this is only available to a small minority of patients [1].

Decompensated cirrhosis is associated with a reduction in albumin production of approximately 60–80 %, as well as alterations in the structure and binding properties of the albumin molecule [8,9]. Intravenous administration of albumin can be used to restore effective volemia in specific acute conditions related to cirrhosis [10]. International guidelines recommend short-term albumin following large-volume paracentesis (LVP) for large or refractory ascites, with antibiotics to treat spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), and with terlipressin for hepatorenal syndrome (HRS)-acute kidney injury (AKI) [7,11].

For patients with decompensated cirrhosis, long-term albumin (LTA) is a potential new treatment paradigm that goes beyond the short-term recovery of acute complications to pursue a durable, chronic replenishment of functional albumin levels and thus could restore the immunomodulatory, colloid osmotic, transport, and endothelium-stabilizing capacities of albumin [4,12]. Two Italian studies have shown that LTA treatment improves outcomes in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites [13,14]. The ANSWER study was a multicenter, randomized trial involving 33 hospitals in Italy [13]. Compared with standard medical treatment (SMT) alone, LTA in combination with SMT significantly reduced mortality, incidence of paracentesis, and the cumulative incidence of cirrhosis-related complications (e.g., refractory ascites, SBP, and renal dysfunction), in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites [13]. Additionally, a non-randomized, prospective real-world study in Italy demonstrated that LTA significantly reduced 24-month mortality and significantly lengthened the period of time free from hospital admissions, compared with the current standard of care (SOC), in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites [14]. As a consequence, the clinical practice guidelines on portal hypertension and ascites by the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver have included LTA among the medical treatment options for patients with ascites, including refractory ascites, with the duration of LTA adapted to the individual patient [15]. Accordingly, many treatment centers in Italy have adopted the use of LTA in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites, and thus, this population provides a unique opportunity to observe the effects of this treatment in clinical practice; which importantly, has the potential to complement and verify the evidence already obtained from clinical trials.

The present study aimed to compare real-world health outcomes in patients with decompensated cirrhosis in Italy who received LTA plus SOC (LTA cohort) versus SOC alone (non-LTA cohort), through a multicenter, retrospective patient chart analysis, using propensity score matching (PSM) to balance the two treatment cohorts for confounding factors.

2Materials and Methods2.1Study designThis retrospective chart analysis was conducted in patients with decompensated cirrhosis treated with LTA plus SOC or SOC alone in Italy. The study observation period ran from January 01, 2019 until December 31, 2021. Anonymized patient medical chart data were collected from treatment centers by Adivo Associates, a global healthcare consultancy engaged by CSL Behring, to undertake the data collection and analysis. Institutions and treating hepatologists/physicians who reported albumin use in patients with liver disease were identified from Adivo Associates’ audit platform and were contacted to obtain the necessary patient medical charts. In addition, centers outside of the audit platform and associated care providers at regional hospitals were contacted and albumin prescribers were identified to gather additional patient charts. Charts were collected evenly across the four defined regions of Italy: Northeast (Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Veneto, Trentino-Alto Adige, Emilia-Romagna); Northwest (Lombardia, Piemonte, Valle d’Aosta, Liguria); Central (Umbria, Toscana, Marche, Lazio); and South (Abruzzo, Campania, Calabria, Basilicata, Molise, Puglia, Sardegna, Sicilia). Only physicians with verified accreditation were contacted and asked to provide the patient chart data. Physicians were clearly informed of the eligibility criteria, and a data collection tool and guidance on how to collect the data were provided. Adivo Associates screened the collected data, and checked for incomplete fields and possible errors, within 24 to 48 h after receipt; any detected inaccuracies were verified via callbacks with the physician. Physicians received a monetary incentive for collection of the data. A patient index was created for each patient with anonymized information, as well as a physician and institution index; these were used to assign each patient chart to a unique identifier. Data collection stopped if a patient switched treatment, received a liver transplant, underwent a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure, or died. The study sponsor (CSL Behring) remained anonymous; the data collection platform was blinded from the study sponsor to ensure unbiased responses and the sponsor did not have access to details of the participating centers, physicians, or patients. As such, the physicians who provided the data have not been involved or identified in this publication. The authors of this publication were not involved in the data collection but were involved in the interpretation of the data.

2.2Study participantsTo be included in the study, patients aged 18 years or older must have been diagnosed with decompensated cirrhosis and must have had ascites leading to paracentesis and treatment with LTA plus SOC or SOC alone during the 12-month period prior to the start of the observation period (January 01, 2019). For the purpose of the study, in the LTA cohort, patients must have completed ≥3 months of LTA treatment prior to the start of the observation period. In the non-LTA cohort, patients must have received albumin for an acute complication at least once in the 12 months prior to the start of the observation period. The full exclusion criteria are presented in the Supplementary Methods. Patients were excluded from participating in the study if they had albumin administered in the 4 weeks prior to inclusion, except for evidence-based indications (therapeutic paracentesis, HRS, SBP), or had previously undergone a liver transplant.

2.3Study treatmentsBoth cohorts (LTA and non-LTA) received SOC, i.e., albumin administered for acute interventions/complications such as LVP, SBP and HRS-AKI, as per the ‘European Association for the Study of the Liver Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis’ [7]. Additionally, in the LTA cohort, patients received LTA infusions at a regular interval (weekly or bi-weekly) with at least 40 g per infusion per week for all age ranges, for a minimum of 3 months. Patients treated with LTA did not receive a loading dose.

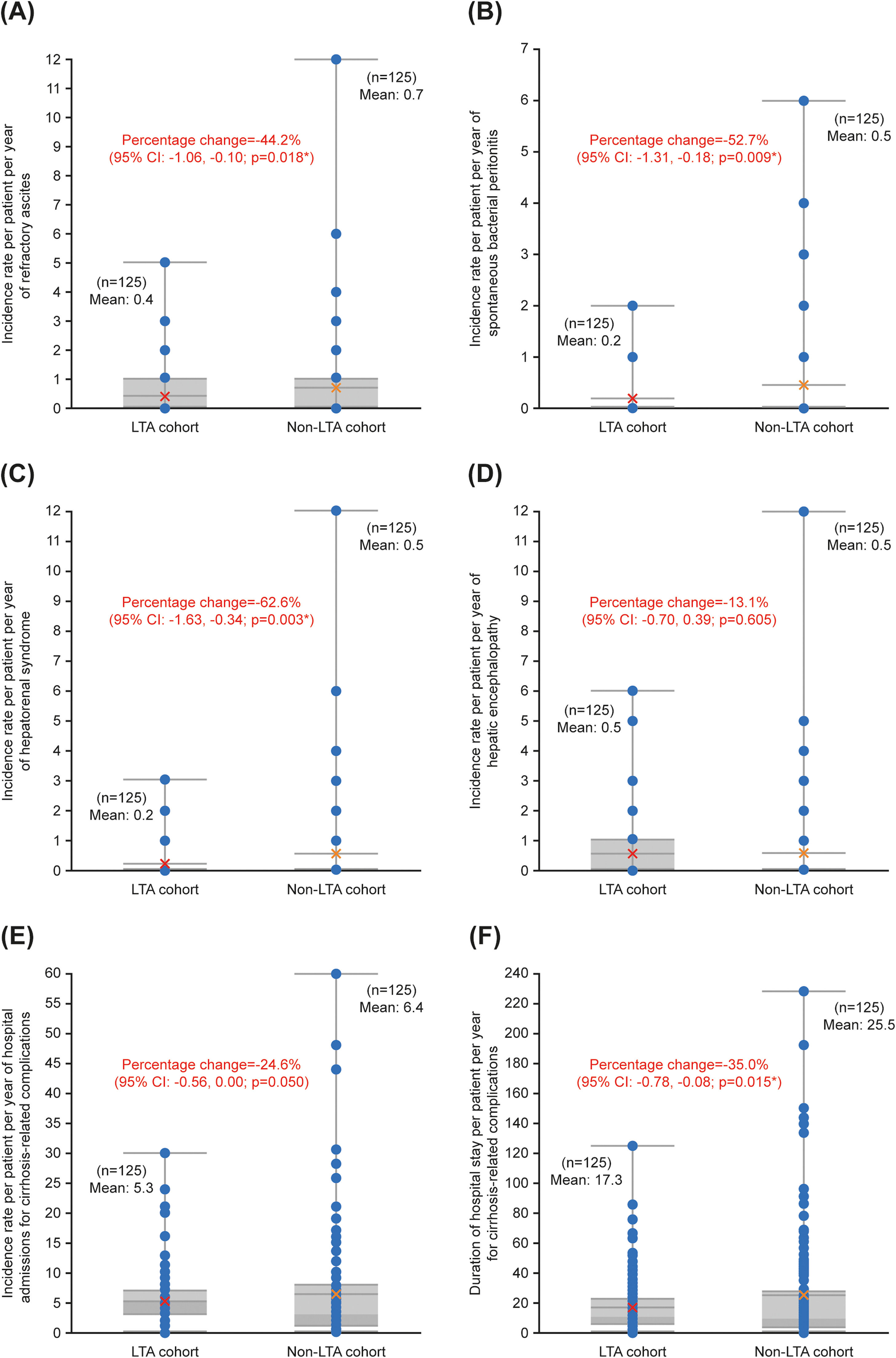

2.4Study endpointsThe primary and secondary endpoints, along with the definitions of each endpoint, can be found in Table 1 [7,16–19]. These definitions were confirmed with participating physicians prior to data collection. The primary endpoint was the incidence rate per patient per year of therapeutic paracentesis procedures in the LTA cohort compared with the non-LTA cohort. Secondary endpoints included comparison between the LTA and non-LTA cohorts of the incidence rates per patient per year of refractory ascites, SBP, HRS, HE, and hospital admissions for cirrhosis-related complications, as well as the duration of hospital stay per patient per year for cirrhosis-related complications, such as refractory ascites, SBP, HRS, and HE. Per year endpoints were based on the calendar year, rates for any patients who discontinued treatment before the end of a calendar year were calculated on a pro-rata basis. The mortality rate and the rate of liver transplant in the two cohorts during the observation period were also secondary endpoints. The sample assessed for liver transplantation excluded all patients who died during the observation period, and the sample assessed for mortality excluded all patients who had a liver transplant during the observation period.

Definitions of the primary and secondary endpoints.

| Endpoint | ICD code | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint: | ||

| Comparison of the incidence rate per patient per year of therapeutic paracentesis procedures between the LTA and non-LTA cohorts | N/A | ‘The percutaneous removal of abdominal fluid’ [16] through a needle or catheter that is inserted into the peritoneal cavity of the patient with cirrhosis.Diagnostic paracentesis was not considered for the study. Therapeutic paracentesis was identified by manual screening of individual patient charts. |

| Secondary endpoints: | ||

| Comparison of the incidence rate per patient per year of refractory ascites between the LTA and non-LTA cohorts | ICD-11, ME04.Z | ‘Ascites that cannot be mobilized or the early recurrence of which cannot be satisfactorily prevented by medical therapy.’[17] |

| Comparison of the incidence rate per patient per year of SBP between the LTA and non-LTA cohorts | ICD-11, DC50.00 | ‘A bacterial infection of ascitic fluid without any intra-abdominal surgically treatable source of infection.’[7] |

| Comparison of the incidence rate per patient per year of HRS between the LTA and non-LTA cohorts | ICD-11, DB99.2 | ‘A potentially reversible syndrome that occurs in patients with cirrhosis, ascites, and liver failure, and in patients with acute liver failure or alcoholic hepatitis. It is characterized by impaired renal function, marked alterations in cardiovascular function, and overactivity of the sympathetic nervous and renin-angiotensin systems.’[18] |

| Comparison of the incidence rate per patient per year of HE between the LTA and non-LTA cohorts | ICD-11, DB99.5 | ‘A characteristic functional and reversible alteration of the mental state due to impaired liver function and/or increased portosystemic shunting. It is a frequent complication of chronic liver disease.’[19] |

| Comparison of the incidence rate per patient per year of hospital admissions for cirrhosis-related complications between the LTA and non-LTA cohorts | N/A | Number of in-patient and out-patient hospital admissions. |

| Comparison of the duration of hospital stay per patient per year for cirrhosis-related complications between the LTA and non-LTA cohorts | N/A | Number of days for in-patient admission and 1 day for out-patient admission. |

| Comparison of the mortality rate between the LTA and non-LTA cohorts | N/A | Number of patients who died during the observation period (all patients who had a liver transplant during the observation period were excluded from the sample). |

| Comparison of the liver transplant rate between the LTA and non-LTA cohorts | N/A | Number of patients who received a liver transplant during the observation period (all patients who died during the observation period were excluded from the sample). |

Abbreviations: HE, hepatic encephalopathy; HRS, hepatorenal syndrome; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; LTA, long-term albumin; N/A, not applicable; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

A targeted sample size of 300 pre-existing patient charts was determined considering power calculations using parameters (reported occurrences and means) based on the ANSWER trial [13], and was further validated through a preliminary PSM exercise on collected patient charts (n = 54). Further information on the sample size calculations can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

A negative binomial generalized linear model (GLM) regression was used to estimate the effect of LTA plus SOC or SOC alone on each endpoint, conducted using the matched pairs created by the PSM model. The PSM methodology estimates the probability (‘propensity score’) of LTA treatment for each patient in both cohorts based on the patient’s demographic characteristics (covariates), consequently balancing the population through matching on the estimated propensity score between cohorts [20]. The matching is a one-to-one match with no replacements through nearest neighbor algorithm [21]. This method limited a single chart from the LTA cohort to be matched with a single chart from the non-LTA cohort, with no chart being matched to multiple charts of the opposite cohort. The caliper width, a specified absolute difference in the propensity score of the matched charts, was 0.0001. The covariates included in the PSM were selected based on their scientific and statistical significance regarding the primary endpoint. Scientific significance was determined by conducting a thorough review of relevant publications and interviews with clinical experts in the field of hepatology. Statistical significance was determined by review of relevant publications to establish if any covariates were statistically significant predictors of having a complication, and by conducting an ordinary least squares test on the unmatched sample. The treatment variable was binary, with patients in the non-LTA cohort defined as zero and patients in the LTA cohort defined as one; definitions of the variables that could be included as covariates within the PSM model are provided in Table S1. Due to collinearity, only one of the disease state scores could be used in the PSM model (Child–Pugh or Model for End-Stage Liver Disease [MELD]). The Child–Pugh score is used to assess prognosis in patients with cirrhosis, whereas the MELD score is most commonly used for the prioritization of patients for liver transplantation [22]; thus, the Child–Pugh score was considered for inclusion in the model instead of the MELD score.

The negative binomial GLM (log-level design) was utilized to adjust for the non-normality of the primary endpoint [23]. The negative binomial GLM’s parameter to model the over-dispersed data better estimates the incidence rates and correlating 95 % confidence intervals (CI). Using this model, a two-sided p-value of <0.050 was considered statistically significant. Liver transplant and mortality rates were not analyzed using this model due to the limited observation period. Statistical analysis was performed with Stata® software (version 15.1 or later).

2.6Ethics statementDue to the double-blinding, this study was exempt from the approval processes of the relevant Institutional Review Boards (IRB) under the IRB exemption criteria 45 CFR 46.104(d)(4), i.e., secondary research for which consent is not required.

3Results3.1Propensity score matchingWhen assessing the scientific significance of the potential covariates for inclusion in the PSM model, sex and the presence of multiple comorbidities (two or more cirrhosis-related comorbidities) indicated the likelihood of the patient having cirrhosis-related complications, and the Child–Pugh score was a direct indicator of the patient’s disease state. Conversely, age and weight did not have a significant impact on the development of cirrhosis-related complications. The dose of LTA given was also not influenced by weight. The region that the patient was treated in directly correlates to the treatment regimen they received due to the different regional reimbursement policies surrounding LTA, and the four regions also have collinearity with each other. During the assessment for statistical significance, the Child–Pugh score (p < 0.001) and the presence of multiple comorbidities (p = 0.004) were found to be significant indicators of the primary endpoint; age, weight, region, and sex were not significant (Table S2). Based on the scientific and statistical significance assessments, sex, Child–Pugh score, and the presence of multiple comorbidities were utilized as covariates for the PSM model. Age, weight, and region were not included in the model.

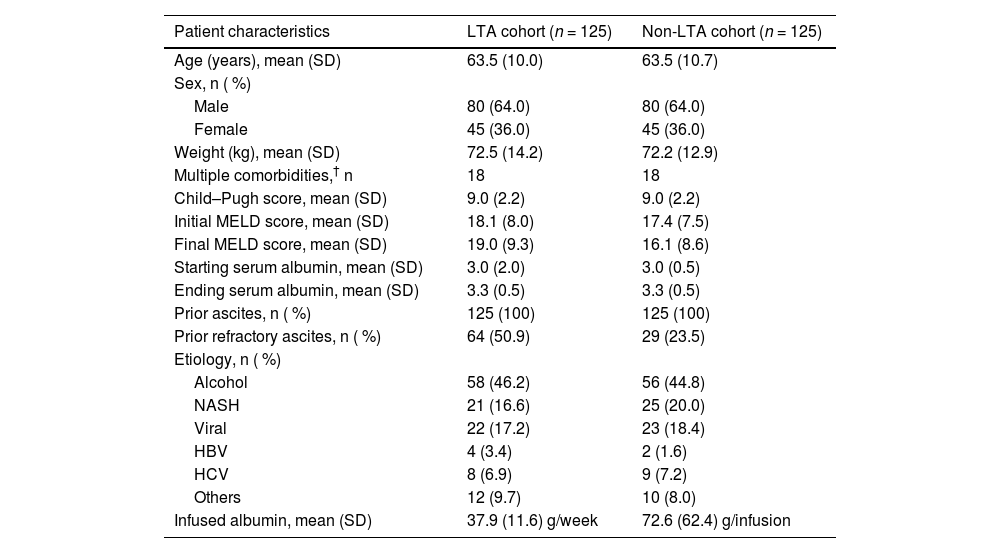

3.2Study populationIn total, 311 patient charts from 14 centers were screened. The mean standard difference of the unmatched sample was 10. After the PSM process, 250 charts were matched (80.4 %); 125 in the LTA cohort and 125 in the non-LTA cohort. The mean standard difference between the cohorts for all three covariates included in the PSM model (sex, Child–Pugh score, and the presence of multiple comorbidities) was 0.0 % for all matched pairs (100 % bias reduction). The etiology of the 250 matched charts was 45.6 % alcohol-related cirrhosis, 18.4 % nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, 18.0 % viral, and 18 % others (Table 2). At the start of the observation period 50.9 % of the LTA cohort, and 23.5 % of the non-LTA cohort had prior refractory ascites (Table 2). Full patient characteristics for the paired cohorts can be found in Table 2. The median follow-up time for both cohorts was 36 months and the mean follow-up time was 28.7 months and 26.2 months for the LTA and non-LTA cohorts, respectively. During the observation period, 16 patients receiving LTA with SOC and 17 patients receiving SOC only discontinued or switched treatment.

Patient characteristics of the matched charts in the LTA and non-LTA cohorts.

| Patient characteristics | LTA cohort (n = 125) | Non-LTA cohort (n = 125) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 63.5 (10.0) | 63.5 (10.7) |

| Sex, n ( %) | ||

| Male | 80 (64.0) | 80 (64.0) |

| Female | 45 (36.0) | 45 (36.0) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 72.5 (14.2) | 72.2 (12.9) |

| Multiple comorbidities,† n | 18 | 18 |

| Child–Pugh score, mean (SD) | 9.0 (2.2) | 9.0 (2.2) |

| Initial MELD score, mean (SD) | 18.1 (8.0) | 17.4 (7.5) |

| Final MELD score, mean (SD) | 19.0 (9.3) | 16.1 (8.6) |

| Starting serum albumin, mean (SD) | 3.0 (2.0) | 3.0 (0.5) |

| Ending serum albumin, mean (SD) | 3.3 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.5) |

| Prior ascites, n ( %) | 125 (100) | 125 (100) |

| Prior refractory ascites, n ( %) | 64 (50.9) | 29 (23.5) |

| Etiology, n ( %) | ||

| Alcohol | 58 (46.2) | 56 (44.8) |

| NASH | 21 (16.6) | 25 (20.0) |

| Viral | 22 (17.2) | 23 (18.4) |

| HBV | 4 (3.4) | 2 (1.6) |

| HCV | 8 (6.9) | 9 (7.2) |

| Others | 12 (9.7) | 10 (8.0) |

| Infused albumin, mean (SD) | 37.9 (11.6) g/week | 72.6 (62.4) g/infusion |

Patients were defined as having multiple comorbidities if they had two or more of the following cirrhosis-related comorbidities: arterial hypertension; atrial fibrillation; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; diabetes; heart disease; obesity; osteoporosis; portal thrombosis; or renal failure.

Abbreviations: LTA, long-term albumin; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; SD, standard deviation.

Using the negative binomial GLM, the incidence rate per patient per year of therapeutic paracentesis procedures had a statistically significant reduction of −47.8 % in the LTA cohort compared with the non-LTA cohort (95 % CI: −0.99, −0.31; p < 0.001). The mean and maximum incidence rates per patient per year of therapeutic paracentesis procedures were 2.2 and 15.7 in the LTA cohort compared with 4.0 and 31.5 in the non-LTA cohort, respectively (Fig. 1). During the observation period, 78.4 % of patients in the LTA cohort and 74.4 % of patients in the non-LTA cohort underwent therapeutic paracentesis.

Incidence rate per patient per year of therapeutic paracentesis procedures in the LTA cohort (LTA plus SOC) compared with the non-LTA cohort (SOC alone). Horizontal boundaries represent (from bottom to top): minimum, median (upper limit of darker grey shaded areas), mean, 3rd quintile, and maximum. Bars for 1st quintile values are indistinguishable from those for minimum values. Red/orange crosses are mean values. Blue circles are individual data points (some overlap). The lower half of the data (0 % to 50 %) is represented by the darker grey shaded areas. *Level of significance: p < 0.050 (negative binomial GLM). Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GLM, generalized linear model; LTA, long-term albumin; SOC, standard of care.

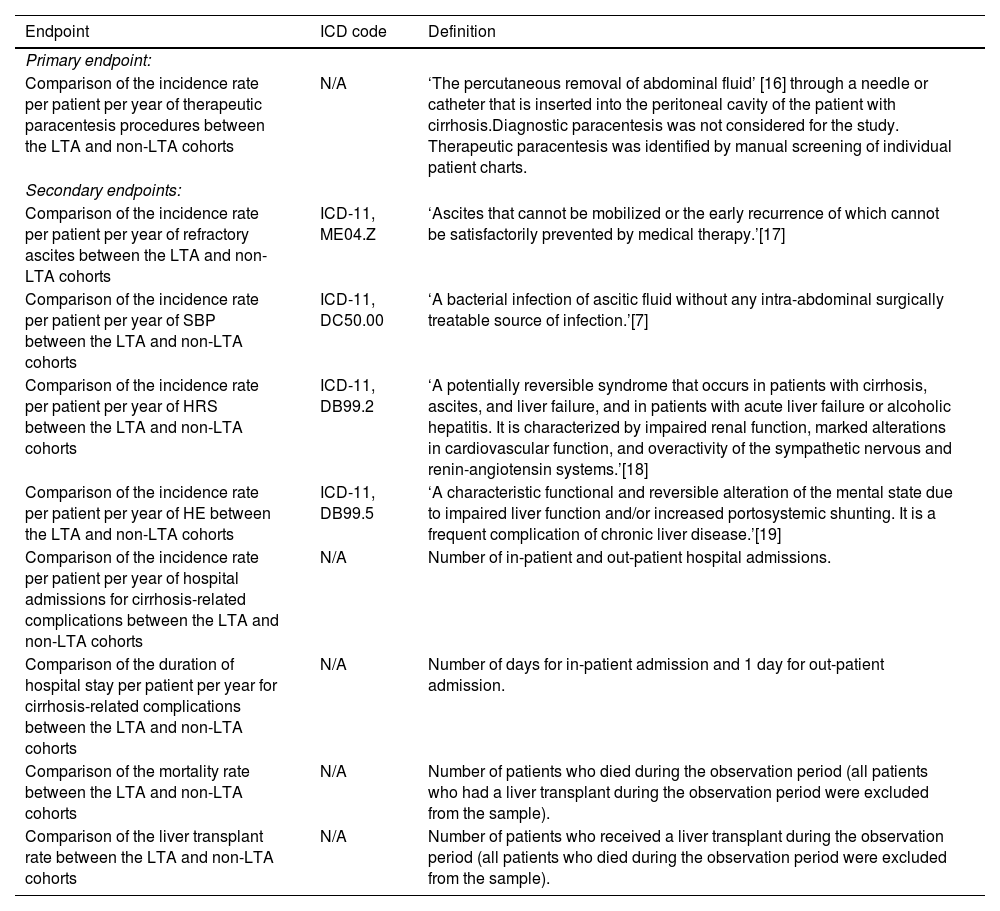

With the negative binomial GLM, incidence rates per patient per year of refractory ascites (−44.2 %; p = 0.018), SBP (−52.7 %; p = 0.009), and HRS (−62.6 %; p = 0.003), as well as the duration of hospital stay per patient per year for cirrhosis-related complications (−35.0 %; p = 0.015), had statistically significant reductions in the LTA cohort compared with the non-LTA cohort (Fig. 2). There were no significant differences between cohorts in the incidence rates per patient per year of hospital admissions for cirrhosis-related complications (−24.6 %; p = 0.050) and HE (−13.1 %; p = 0.605) (Fig. 2).

Comparison between the LTA cohort (LTA plus SOC) and non-LTA cohort (SOC alone) for the secondary endpoints assessed using the negative binomial GLM. Incidence rate per patient per year of (A) refractory ascites, (B) spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, (C) hepatorenal syndrome, (D) hepatic encephalopathy, (E) hospital admissions for cirrhosis-related complications, and (F) duration of hospital stay per patient per year for cirrhosis-related complications. Horizontal boundaries represent (from bottom to top): minimum, median (upper limit of darker grey shaded areas), mean, 3rd quintile, and maximum. Bars for 1st quintile values are indistinguishable from those for minimum values. Red/orange crosses are mean values. Blue circles are individual data points (some overlap). *Level of significance: p < 0.050 (negative binomial GLM). Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GLM, generalized linear model; LTA, long-term albumin; SOC, standard of care.

In total, 104 patients in the LTA cohort and 95 patients in the non-LTA cohort were included in the sample for assessment of the liver transplant rate, and 118 patients in the LTA cohort and 114 patients in the non-LTA cohort were included in the sample for assessment of the mortality rate. The proportion of patients that underwent a liver transplant or died during the observation period was 7 % and 22 % in the LTA cohort, respectively, and 12 % and 26 % in the non-LTA cohort, respectively. It should be noted that four patients in the LTA cohort and three patients in the non-LTA cohort underwent a TIPS procedure during the observation period.

4DiscussionInternational guidelines recommend short-term albumin in specific acute conditions related to decompensated cirrhosis, such as following LVP for ascites and in the treatment of SBP and HRS-AKI [7,11]. In addition, recent data from Italy, such as the large-scale ANSWER trial, have shown that LTA treatment improves outcomes in selected patients [13,14]. While short-term albumin substitution aims to impact a single complication, LTA endeavors to alter the course of the disease, provided it is given at a sufficient dose for a sufficient period of time [4].

This multicenter, retrospective chart analysis using PSM examined real-world outcomes in patients with decompensated cirrhosis in Italy who received LTA for ≥3 months with SOC, compared with those who received SOC alone. The use of LTA plus SOC, compared with SOC alone, significantly reduced the incidence rates per patient per year of therapeutic paracentesis procedures, refractory ascites, SBP, and HRS, as well as the duration of hospital stay per patient per year for cirrhosis-related complications. There were no significant differences in the incidence rates per patient per year of hospital admissions for cirrhosis-related complications and HE, as well as no differences in the mortality and liver transplant rates, between the two cohorts. This real-world evidence of the benefits of LTA therapy in patients with decompensated cirrhosis supports the findings from previous studies and demonstrates how they have been successfully transferred into clinical practice in Italy.

The results are consistent with many of the findings from the ANSWER study, in which the incidence rate of therapeutic paracentesis, the primary endpoint of our real-world chart analysis, was significantly reduced by 54 % in patients receiving LTA plus SMT compared with SMT alone [13]. Similarly to our study, the ANSWER study demonstrated significant reductions in the cumulative incidence of refractory ascites, SBP, and HRS type 1, as well as a significant reduction in the total duration of hospitalizations per patient per year, in patients treated with LTA plus SMT compared with SMT alone [13]. There was also no difference in the liver transplant rate between cohorts in the ANSWER study [13]. However, unlike the ANSWER study [13], we did not find a significant difference in the incidence rates per patient per year of hospital admissions for cirrhosis-related complications and HE, or a difference in the mortality rate, between cohorts. The lack of a significant difference in mortality in this study, despite the numerical difference (22 % vs 26 %), could be due to the number of patients enrolled (n = 250), which limits the statistical power. Duration of follow-up may also be a factor in this observation; patients in the ANSWER study were treated for 18 months and 18-month survival was significantly improved with LTA, whereas median follow-up in this study was 36 months. The difference in mortality rates between the studies, which were higher in ANSWER, given the difference in follow-up makes interpretation difficult. In relation to hospital admission rates, while there was no significant difference between the groups, the total duration of hospitalization differed significantly, meaning that LTA-treated patients either had less severe complications at hospital admission or complications resolved more rapidly after hospital admission than those of patients who received SOC alone.

The addition of LTA has also been reported to demonstrate clinically meaningful improvements in transplant-free survival, disease-related complications and mortality rates in the top-line results of the global, multicenter PRECIOSA study (NCT03451292) investigating the use of LTA plus SMT compared with SMT alone in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites [24]. However, the primary endpoint (significant improvement in 1-year transplant-free survival powered to ≥80 %) was not met. Of note, in the PRECIOSA study, LTA raised and maintained the mean serum albumin concentrations in the treatment group by 0.5–0.65 g/dL, compared with the control group. Unlike the PRECIOSA study, a difference in serum albumin concentrations was not observed in this study. We believe this could be due to a combination of several factors, including the lower albumin dose used compared with the PRECIOSA study (37.5 g/week versus 1.5 g/kg body weight up to 100 g, every 10 ± 2 days), combined with treatment discontinuations, especially over such a long timeframe in real-life practice, as well as the non-randomization of patients, which meant the LTA group initiated albumin treatment from a worse clinical situation than the non-LTA group. Moreover, although this remains a hypothesis yet to be demonstrated, clinical experience suggests that more severely ill patients (such as those in the LTA group) may require higher doses of albumin to achieve a significant increase in serum albumin levels.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the retrospective nature of the study based on chart analysis means that control over data collection and recording, and outcome assessment is limited, potentially introducing variability. The data collected were limited to those required to assess the predefined endpoints, meaning that we do not have insight into measures such as mean amount of fluid removed at paracentesis. Such data could have provided further insight into the value of LTA treatment. Secondly, the sample size may have limited the ability to identify significant differences between the treatment groups, which potentially explains the difference in outcomes to those reported for the ANSWER trial [13]. Thirdly, the requirement that patients had to have been receiving LTA treatment for at least 3 months prior to observation in the study excludes patients who discontinued treatment before reaching this threshold. Therefore, the study conclusions can be applied only to those patients who remained on LTA therapy for ≥3 months, which may have selected for a group that did not have poor outcomes and were able to tolerate LTA therapy. Finally, some data on LTA treatment-related modalities, such as setting of albumin infusions and temporary or permanent interruption of treatment, were not investigated. Other potential limitations included institutional and physician treatment biases based on hospital policy and the influence of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic during the study observation period. However, it should be noted that most physicians who provided patient data for the study treated patients who were included in both the LTA and LTA with SOC groups.

LTA is a new model of care for patients with decompensated cirrhosis, requiring weekly visits to a healthcare setting for infusion [13]. As a result of this treatment regimen, patients will have increased contact time with members of the healthcare team. This regular contact may result in better general management, earlier identification of complications, and quicker treatment of complications by the healthcare team [25]. Additionally, regular contact with the healthcare team may have a positive influence on patient adherence to care [26]. While these benefits may bias the results reported here, it should be noted that because this increased contact is a normal part of the care pathway for LTA, the real-world efficacy of this treatment regimen includes the associated benefits of more regular patient interactions with healthcare professionals.

Italy was the first country to adopt the use of LTA in patients with decompensated cirrhosis in clinical practice. Our study builds on the evidence base of the effectiveness of LTA when used for ≥3 months in Italy, providing a rationale for use in other countries. However, it should be considered that there may be barriers to the extension of LTA to other countries, such as high costs and supply issues associated with albumin [27]. Further research specifically focused on the cost-effectiveness of LTA plus SOC versus SOC alone is needed prior to the inclusion of LTA in the guidelines for the management of decompensated cirrhosis in other countries or continents. However, our study does suggest that the use of LTA therapy has the potential to lower healthcare resource utilization due to a reduction in cirrhosis-related complications and duration of hospitalizations.

5ConclusionsThis study provides real-world evidence of the benefits of LTA therapy when used for ≥3 months in patients with decompensated cirrhosis in Italy, further supporting the positive outcomes demonstrated in the ANSWER trial [13]. LTA therapy has the potential to improve the care of patients with decompensated cirrhosis and reduce the related healthcare resource utilization.

Author contributionsData collection and analysis was undertaken by KR and SS. XZ was involved with the design of the statistical analysis. All authors were involved with data interpretation, review of the manuscript, and approval of the final version.

WL has received consultancy fees from CSL Behring, Belgium; JT has received speaking and/or consulting fees from Versantis, Gore, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Falk, Grifols, Genfit and CSL Behring; AOB has received consultancy/speaker fees from Novartis, Grifols, Mallinckrodt, and GSK; GZ has received speaking and/or consultancy fees from Grifols SA, Octapharma AG, and PPTA. PC has received research grants from Grifols SA and Octapharma SA, and personal fees from Grifols SA, Octapharma SA, CSL Behring SA and Takeda SA; JFR, XZ and MK are employees of CSL Behring; KR and SS are employees of Adivo Associates; PA has received speaking and/or consultancy fees from BioVie, Gilead (Italy), CSL Behring, Grifols and Ferring, and grants from Gilead (Italy) and CSL Behring (travel grant).

Data collection and analysis was undertaken by Adivo Associates and funded by CSL Behring. Editorial assistance was provided by Bioscript Group (Macclesfield, UK), in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines, and funded by CSL Behring. As the study was double-blinded, the physicians who provided the data have not been involved or identified in this publication.