The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, initially developed to predict short-term mortality in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, is now central to liver transplant allocation and broader prognostic applications [1,2]. MELD 3.0, incorporating albumin and sex, was recently introduced to enhance predictive accuracy [3]. However, in hospitalized patients with decompensated cirrhosis, many of whom are not transplant candidates, the utility of these scores remains less certain [4,5]. This is important as we commonly use these scores for clinical decision making on the wards, such as appropriateness of intensive care transfer or palliative measures, as well as for discussions with relatives of the patients.

To address this, we analyzed data from the ATTIRE trial, a multicenter randomized clinical trial evaluating albumin infusions in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis [6]. The trial enrolled 777 patients across the UK, excluding those with advanced HCC or under palliative care. Baseline parameters permitted calculation of MELD and MELD 3.0 scores. The primary outcome of the current analysis was 90‑day all-cause mortality.

The cohort had a mean age of 54 years (±11) and 71 % were male. The predominant etiology of liver disease was alcohol-related cirrhosis, accounting for 90 % of cases. At admission, 67 % of patients presented with new-onset or worsening ascites. Most (97 %) were admitted for ward-based management, with 3 % admitted directly to intensive care units. Liver transplantation was performed in <1 % (n = 4) during 90-day follow-up.

The median MELD score at baseline was 20 (interquartile range [IQR]: 15–23), while the median MELD 3.0 score was 23 (IQR: 18–27). Ninety-day mortality occurred in 185 patients (24 %). To evaluate the predictive performance of MELD and MELD 3.0, we compared their C-statistics, a measure of discriminative ability (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve). MELD yielded a C-statistic of 0.675, while MELD 3.0 modestly improved this value to 0.699, suggesting a statistically but not clinically significant enhancement in discriminatory power [7].

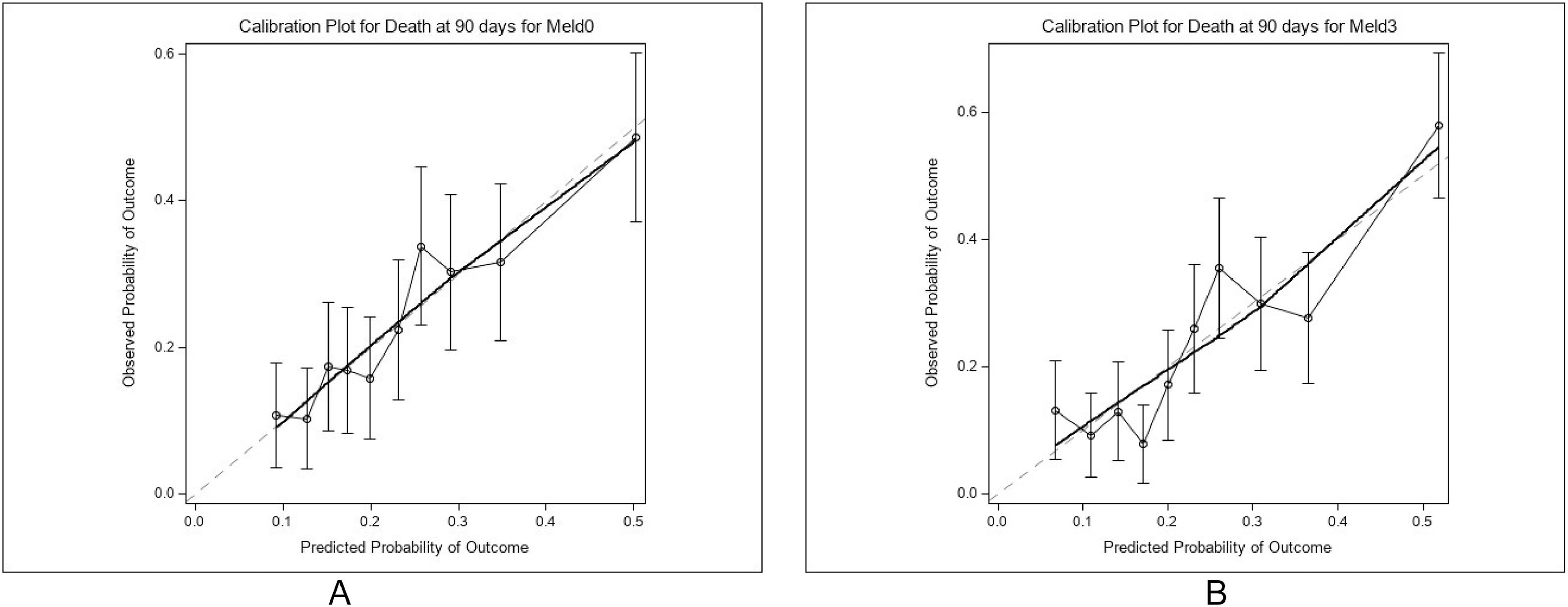

Model fit was assessed using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), with MELD 3.0 demonstrating a significantly improved fit over MELD (p = 0.0003). However, calibration, defined as the agreement between predicted and observed mortality, was suboptimal for MELD 3.0 (Hosmer-Lemeshow test p = 0.0295), indicating a mismatch between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes. In contrast, MELD displayed adequate calibration, albeit with inferior discrimination.

These findings highlight several points. First, both scores underperform in ward-based cohorts with limited transplant access [8]. Second, MELD-based models omit important contributors to prognosis such as systemic inflammation, frailty, and comorbidities, potentially limiting their applicability in acutely decompensated patients [9,10]. Third, reliance on MELD for clinical decision-making in predominantly alcohol-related cirrhosis may result in misclassification and ethical dilemmas in end-of-life care [11]. Therefore, we urge clinicians to incorporate other factors that are not included in these scoring systems into their decision-making, such as age, co-morbidity, nutritional status, disease trajectory and likelihood of receiving a liver transplant within the short term. Fig 1

Our study benefits from a large, well-characterized cohort drawn from diverse clinical settings. Limitations include post hoc analysis, exclusion of palliative and advanced HCC partients, and generalizability restricted to a Western, alcohol-predominant population, although this may be more prominent globally than previously estimated.[12,13] It should be noted that MELD 3.0 consistently demonstrated strong discriminative ability, when compared to MELD, particularly in relation to long-term mortality in a Chinese cohort [14].

In conclusion, MELD and MELD 3.0 offer limited prognostic value in hospitalized patients with decompensated cirrhosis. While MELD 3.0 provides minor statistical improvements, its poor calibration diminishes clinical utility. Prognostic models tailored to this distinct inpatient context such as CLIF-SIG warrant further validation and implementation [15].

None.