Aim:To estimate the incidence of Biliary Atresia(BA) amongst Neonatal Cholestatic Syndromes (NCS) and determine prognostic factors in BA patients who have undergone Kasai’s portoenterostomy. Study design-Retrospective analysis. Setting-Pediatric Hepatobiliary Clinic at B.J. Wadia Children’s Hospital, Mumbai.

Methods and materials: 32 patients diagnosed with BA referred to the clinic from May 2005 to July 2007 were included in the study. All patients underwent a detailed history, clinical examination and were tested for Liver function tests (LFT), USG abdomen, Liver biopsy, intra-operative cholangiogram and CMV tests. Patients were followed up for a period of 1 month to 7 years post operatively and complications such as cholangitis, progress to liver cell failure and cirrhosis was noted.

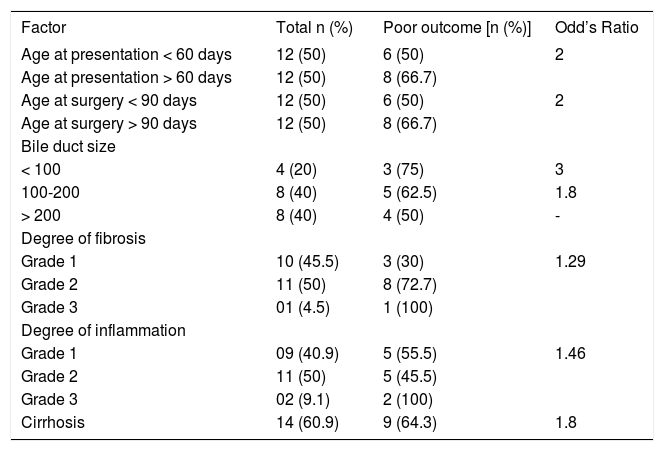

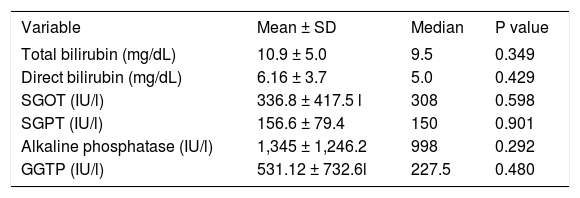

Results: Incidence of BA amongst NCS (n = 88) was 36.4%. 8 patients of BA (25%) were lost to follow up. Out of the remaining, 10 (41.7%) improved and 14 (58.3%) did not improve. The mean age of presentation was 89 ± 55.8days. 1 patient (25%) out of 4 with bile duct size of < 100 microns showed an improvement whereas 3 (37.5%) out 8 patients with bile duct size 100-200 microns showed improvement and 4 (50%) with bile duct size of > 200 microns had improvement post Kasai surgery. Those with bile duct sizes > 200 microns had better prognosis than those with sizes 100-200 microns (Odd’s ratio = 1.8) and < 100 microns (Odd’s ratio = 3). 12 patients (50%) were operated before 3 months of age and 50% of them responded to surgery. The remaining 12 patients were operated after 3 months of age and only 33% showed any improvement. (Odd’s ratio = 2). Other parameters like SGOT (P = 0.598), SGPT (p = 0.901), total Bilirubin (p = 0.349), Direct Bilirubin (p = 0.429), Alkaline Phosphatase (p = 0.605) and GGTP (p = 0.480), cirrhosis (p = 0.417), degree of fibrosis (p = 0.384), degree of inflammation (p = 0.964) and Cholangitis (P = 0.388) had no effect on the outcome.

Conclusion: Biliary Atresia is a common cause of NCS in India. Children with Bile duct size > 200 microns have a good prognosis. Portoenterostomy before 3 months of age has a better outcome.

Biliary atresia (BA) is the commonest of the rare neonatal cholestatic syndromes (NCS), occurring in approximately 1 of 8,000 to 12,000 live births, with a female preponderance, characterized by complete fibrotic obliteration of the lumen of all or part of the extrahepatic biliary tree within 3 months of life.1 Left untreated it leads to cirrhosis and liver cell failure with eventual death. With the advent of Kasai portoenterostomy, children have a promise for long term survival. Outcomes data from centers throughout the world demonstrate considerable variability, with initial success of the Kasai portoenterostomy (for achieving bile flow) ranging from 60-80%.2 The success of Kasai portoenterostomy depends on the age at time of referral, age at time of surgery,3 presence of jaundice, presence of clay colored stools, levels of total and direct bilirubin,4 SGOT, SGPT, Alkaline phosphatase and Gamma Glutamyl Transferase (GGTP),5 presence or absence of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection,6 presence of cirrhosis, presence and degree of fibrosis on liver biopsy, bile duct size and inflammation in the liver.7-9 The prognosis after a Kasai portoenterostomy have not been adequately analyzed in the Indian setting. We plan to delineate prognostic factors in patients of Biliary Atresia who have undergone Kasai portoenterostomy. Understanding these factors will become an important subject in the prediction of the postoperative status and in indicating further proper management.

Material and methodsThis retrospective study was undertaken at Pediatric Hepatobiliary Clinic at B.J. Wadia Children’s Hospital, Mumbai. Thirty two patients diagnosed with BA referred to the clinic from May 2005 to July 2007 were included in the study. It also included patients who had been diagnosed as Biliary Atresia earlier and were referred to the clinic during the study period. Patients with NCS without BA were excluded from the study. All patients had undergone a detailed history and thorough clinical examination and were tested for Liver function tests, Ultrasound abdomen, Liver biopsy and intra-operative cholangiogram. Additional investigations in the form of CMV tests (CMV PCR/ CMV IgM ELISA), radioisotope liver scan, metabolic screening (urinary aminoacidogram, serum alpha-1 antitrypsin levels were done as and when required. Patients with BA were offered Kasai portoenterostomy. Patients were followed up for a period of 1 month to 7 years post operatively. Complications such as cholangitis, number of episode of cholangitis, progress to liver cell failure and cirrhosis were noted. Cholangitis was defined as appearance of fever with clay colored stools, leucocytosis and/or vomiting, abdominal distension and bacteremia. Non improvement of jaundice within 3 months of surgery, progression to liver cell failure and persistence of clay colored stools was determined as failure of Kasai portoenterostomy. Patients who were jaundice free without liver cell failure were classified as response to Kasai’s operation. Patients with a failed Kasai’s surgery were counseled regarding liver transplantation.

Markers such as age at referral, age at surgery, days of presence of jaundice and clay colored stools, levels of total and direct bilirubin, SGOT, SGPT, alkaline phosphatase and GGTP, presence of CMV infection, presence of cirrhosis, presence and degree of fibrosis, presence and degree of inflammation and bile duct size (< 100 microns, 100-200 microns and > 200 microns) were analyzed to determine the prognosis of operated biliary Atresia.

Statistical analysisStatistical tests like chi square test, Kruskaal-Wallis and Odd’s ratio were used for the analysis which was done using SPSS software. p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

ResultsIncidence of BA was 36.4% among all infants with neonatal cholestasis. 8 patients of BA were lost to follow up and excluded from the study. Remaining 24 patients underwent Kasai Portoenterostomy. No patient underwent liver transplant due to unaffordability and lack of donors. The mean age at presentation was 89 ± 55.8 days with a median of 60 days. The mean age at surgery was 109 ± 66.9 days with a median of 88.5 days. Earlier age of presentation and earlier age of surgery is associated with better outcome as depicted in Table I. Male: Female ratio was 2:1. Data of liver biopsies of 23 patients was collected and analyzed. All of them showed fibrosis and inflammation. 14 (60.9%) showed cirrhosis. Analysis of liver biopsy factors has been presented in table 1. Amongst patients < 90 days old at surgery, one (8.3%) had bile duct size of < 100 •, five (41.67%) had bile duct size of 100-200 • and 6 (50%) had size > 200 •. Amongst those > 90 days old at surgery, 3 (37.5%) had bile duct size < 100 •, 3 (37.5%) had bile duct size of 100-200 • and 2 (25%) had size of > 200 •. Hence, bile duct size varied inversely with age (Odd’s ratio 3). Those with bile duct sizes > 200 microns had better prognosis than those with sizes 100-200 microns (Odd’s ratio = 1.8) and < 100 microns (Odd’s ratio = 3).

Factors predicting poor outcome.

| Factor | Total n (%) | Poor outcome [n (%)] | Odd’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at presentation < 60 days | 12 (50) | 6 (50) | 2 |

| Age at presentation > 60 days | 12 (50) | 8 (66.7) | |

| Age at surgery < 90 days | 12 (50) | 6 (50) | 2 |

| Age at surgery > 90 days | 12 (50) | 8 (66.7) | |

| Bile duct size | |||

| < 100 | 4 (20) | 3 (75) | 3 |

| 100-200 | 8 (40) | 5 (62.5) | 1.8 |

| > 200 | 8 (40) | 4 (50) | - |

| Degree of fibrosis | |||

| Grade 1 | 10 (45.5) | 3 (30) | 1.29 |

| Grade 2 | 11 (50) | 8 (72.7) | |

| Grade 3 | 01 (4.5) | 1 (100) | |

| Degree of inflammation | |||

| Grade 1 | 09 (40.9) | 5 (55.5) | 1.46 |

| Grade 2 | 11 (50) | 5 (45.5) | |

| Grade 3 | 02 (9.1) | 2 (100) | |

| Cirrhosis | 14 (60.9) | 9 (64.3) | 1.8 |

Biochemical markers were not significantly associated with re-coloration of stools and clinical improvement post surgery (Table II.). Eleven (84.6%) patients out of 13 tested had CMV infection. Of these 4 (36.4%) were treated with anti CMV medications. Postoperatively, 8 patients (33.3%) had cholangitis. However presence of cholangitis did not lead to a poor outcome (P = 0.388). 10 (41.7%) became jaundice free and had yellow stools; 12 (50%) did not improve and 2 (8.33%) died.

Biochemical markers and their association with outcome.

| Variable | Mean ± SD | Median | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 10.9 ± 5.0 | 9.5 | 0.349 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 6.16 ± 3.7 | 5.0 | 0.429 |

| SGOT (IU/l) | 336.8 ± 417.5 l | 308 | 0.598 |

| SGPT (IU/l) | 156.6 ± 79.4 | 150 | 0.901 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/l) | 1,345 ± 1,246.2 | 998 | 0.292 |

| GGTP (IU/l) | 531.12 ± 732.6l | 227.5 | 0.480 |

BA is a disease of unknown etiology and if left untreated, has a progressive course to end stage liver failure and death. Contrary to some studies from the west which suggest a female preponderance,10,11 our study shows a male: female ratio of 2:1. Bile drainage can be restored by Kasai porto-enterostomy and surgery must be performed before the intra hepatic ducts leading to the porta hepatis are destroyed.5,12 In our study, 10 (41.7%) out of the 24 patients showed restoration of bile flow, re-coloration of stools and clinical improvement during the follow up period. Long term survival of these patients has varied 15.9 to 40.5% at different centers.2,5 Hence, most of the patients require liver transplant to ensure good survival. Several studies confirm that surgery before 3 months of age (8 weeks in some studies) had better chances of achieving effective bile drainage.2-4 In our study, patients less than 90 days old at the time of surgery had a significantly better prognosis. Also, bile duct size had an inverse correlation with age with more number of children less than 90 days at surgery having a bile duct sixe > 200 • and better prognosis which is in conformation with Bhatnagar et al13 but contradicts the study done by Tan et al.7 Hence an early surgery is advised. However, the upper limit for surgery cannot be made strict since improvement was seen in patient as old as 165 days. The major hurdle in performing early surgery in our study was the late mean age of referral almost after 2.5 months of life as has been a problem in India as well as abroad.2,11

11 (60%) out of 13 who were tested had associated CMV infection which is much higher than 24% reported by Tarr PI et al.12 However, more number of patients needs to be tested in order to derive a conclusion regarding the association of CMV with BA.

Langenburg et al. have found in their study that bile duct size at porta hepatis does not predict success of portoenterostomy9 while Gautier et al. have shown that larger ducts at the porta hepatis were associated with better bile flow from transected porta.14 However, in our study patients having bile duct size > 200 • had a better outcome in terms of restoration of bile flow, recoloration of stools and clinical improvement than others having smaller bile ducts.

Biochemical profile of the patients helped in assessment of the patient’s status pre and post operatively but were not significantly associated with recoloration of stools and clinical improvement post surgery.

Several factors affect the success of portoenterostomy in infants with BA. Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia with or without clay colored stools should be considered for urgent hepatobiliary reference to an appropriate center as delay in surgery leads to a decrease in bile duct size over a period of time and a poorer prognosis. The survival rate being poor, liver transplants should be made more feasible.

This study has its limitations due to a small cohort and lack of long term follow up. Therefore, a study with more number of patients and follow up of long term outcome is the need of the hour.

ConclusionBiliary Atresia is a common cause of NCS. Early diagnosis with early surgery is associated with better outcome.