Background and Aims. There are limited data on clinical and phenotypic characteristics of outpatients referred for hyperferritinemia (HF). To determine the causes of HF in outpatients referred to a secondary hospital.

Material and methods. A prospective study of 132 consecutive patients with HF (> 200 μg/L, women; > 300 μg/L, men) was conducted from January-December 2010.

Results. Mean age, 54.42 years (SD: 13.47, range: 23-83); body mass index (BMI), 28.80 (SD: 3.96, 17-39); ferritin (SF), 579.54 ng/mL (SD: 296.575, 206-1668); transferrin saturation (TSI), 43.87% (SD: 14.09, 12-95); iron (Fe), 134 μg/dL (SD: 49.68, 55-322); overweight: 48.31%, and obese: 40.44% (89%), and most patients were men (108/132). Regarding HFE mutations, H63D/H63D genotype and H63D allele frequencies were 17.5% (vs. 7.76% in controls); and 36% (31% in controls) respectively. While 63.6% consumed no alcohol, 18.1% consumed ≥ 60 g/day, the mean being 20.83 (SD: 33.95, 0-140). Overall, 6/132 (4.5%) patients were positive for B or C hepatitis. Mean LIC by MRI was 36.04 (SD: 32.78, 5-210), 53 patients having normal concentrations (< 36 µmol/g), 22 (33%) iron overload (37-80), and 4 (5%) high iron overload (> 80). Metabolic syndrome (MS) was detected in 44/80 men (55%) and 10/17 women (59%). In this group, the genotype frequency of the H63D/H63D mutation was significantly higher than in controls-21.56% vs. 7.76%- (p = 0.011); the H63D allelic frequency was 42.15% in MS group and 31% in controls (p = 0.027).

Conclusion. The H63D/H63D genotype and H63D allele predispose individuals to HF and MS. MRI revealed iron overload in 33% of patients.

SF values are frequently requested by clinicians.1 Raised levels of SF is a common finding in routine laboratory tests. Such patients are referred to an outpatient hospital consultation for testing for HF and genetic hemochromatosis.1–5 Raised SF levels may be present in various different clinical conditions, such as inflammatory diseases, and specifically in renal, hepatic and neoplastic diseases. In patients with liver disease, raised serum ferritin is characteristic of hereditary hemochromatosis, but may also be found in patients with chronic hepatitis C, alcoholic or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.3,6

Epidemiological studies on hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) in Mediterranean populations have shown that the prevalence of C282Y is lower than in Northern European countries,3,7 and that the H63D mutation is found among 15-20% of the general population.3,8 In the Basque Country, the allele frequency is as high as 30%.7

There are limited data in the literature on clinical and phenotypic characteristics of outpatients referred for HF.1 Specifically, there has been very little research on epidemiologic factors including alcohol, viral hepatitis, obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Nowadays, to determine whether (or not) an individual has liver iron overload, there is a very useful radiological tool, namely the measurement of LIC by MRI.9,10 When validated, with values being strongly correlated with those determined biochemically, and standardized, LIC values obtained by MRI are as useful as those obtained by liver biopsy.9–11

The objectives of our study were to prospectively analyse consecutive patients referred to the outpatient clinic of a secondary hospital in the Basque Country and to determine the causes of the HF as well as the relevance of HFE gene mutations and liver iron measurement by MRI in the diagnosis.

Material and MethodsPatientsThis was a prospective study including patients from January to December 2010. The study was conducted in Mendaro Hospital, Deba Valley, a secondary hospital in the Basque Health Service (Osakidetza), with a total catchment of 70,000 people.

Inclusion criteria: consecutive outpatients referred for HF (> 200 μg/L in women, > 300 μg/L in men), in accordance with the WHO criteria,1,3 by their General practitioners were eligible to participate in the study provided that they were aged 18 years or older.

Exclusion criteria: systemic inflammation, infections, and renal, or neoplastic diseases (excluded by clinical, laboratory and radiologic methods).

Methods- •

Radiology.

- a)

MRI. MRI images were obtained with a 1.5-Tesla system (Philips Intera, Osatek, Donostia). The MRI technique used (SIR method) was that proposed by Alustiza, et al.10 As steatosis is frequent, we systematically perform T1-weighted in-phase and opposedphase imaging to discard liver steatosis. All the iron quantification sequences were inphase sequences to be sure that the fat did not interfere in signal intensity measurements.12 The LIC calculated by this model has a high correlation with biochemical measurements, obtained by atomic spectrometry, in liver biopsy samples (r = 0.937).10 The LIC was considered as: normal (< 36 µmol/g), iron overload (IO) (37-80 µmol/g), and high iron overload (HIO) (> 80 /miol/g).10 We have also studied the presence of liver fat. Steatosis was classified as absent or present.

- b)

Abdominal ultrasound. Steatosis was graded by ultrasound and classified as absent or present.3

- a)

- •

Laboratory measurements. SF, Fe and TSI were obtained from blood samples taken fasting from all the patients included. All were found to have raised SF values (> 300 μg/L), the laboratory normal range for SF being 15 to 200 µg/L in women and 30 to 300 µg/L in men.1,3 The ranges considered to be normal for Fe and TSI were 50-145 µg/dL and 15-45% respectively.

The serum values of ALT, AST, GGTP, alkaline phosphatase, bilirrubin, albumin, glucose, cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, etc., were obtained from the same blood samples.

- •

HFE mutation analysis. DNA was extracted from the blood samples and HFE gene analysis was performed by multiplex real-time PCR using LightCycler technology (LC 1.0). Simultaneous detection of the HFE C282Y, H63D and S65C mutations was carried out in a single capillary using LC-Red 640, LC-Red 705 and fluorescein-labelled hybridization probes (Tibmolbiol, Berlin, Germany). Melting curve analysis was used to distinguish wild type and mutant alleles in each case.

The results were compared with a control group of blood donors from the same geographical area, Guipuzcoa.7

- •

Definition of metabolic syndrome (MS). We employed established criteria,13 namely.

- °

Waist circumference ≥ 94 cm in men; ≥ 80 cm in women, and two of the following factors.

- °

Triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL or treatment for this dyslipidaemia.

- °

HDL < 40 mg/dL women, < 50 mg/dL men or treatment for this dyslipidaemia.

- °

Glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or type 2 diabetes.

- °

Hypertension: systolic pressure ≥ 130 mmHg; diastolic pressure ≥ 85 mmHg, or treatment for arterial hypertension.

- °

Overweight or obesity, where a body mass index (BMI) < 25 was considered normal; BMI > 25 and < 30, overweight; and BMI > 30, obesity.6

- °

The information about type 2 diabetes and treatment for hypertension or dyslipidaemia was collected from the interview with the patient.

- •

Alcohol consumption. Heavy drinking was defined as the consumption of > 60 g/day;8,14 while > 40 g/day was considered moderate alcohol consumption. The information was collected from the interview with the patient.

- •

Statistics. SPSS 15.0 software (SSPS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform the appropriate statistical analyses. Mean values with range and standard deviation were calculated for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables.

To compare HFE mutation frequency in patients with HF and the control group, we used Chisquare and Fisher’s exact tests, due to the small number of cases. In all the analysis, a p < 0.05 value was considered statistically significant.

- •

Ethics. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the understanding and the consent of the patients. The study was approved by the Mendaro Hospital Ethics Committee.

A total of 132 patients fulfilling the selection criteria were included in the study. There was a male predominance of approximately 4:1 (108 men, 24 women).

Not all the results were available for all the patients.

RadiologyAbdominal ultrasound was suggestive of steatosis in 69/132 (52.3%), and normal in 44 (33.3%), with other findings in the remaining cases (14.4%).

LIC was obtained by MRI in 79/132 patients. The mean LIC was 36.04 µmol/g (SD: 32.78, 5-210), 53 patients having normal concentrations (<36 µmol/ g), 22 IO (37-80 µmol/g), and 4 HIO (> 80 µmol/g), 50% with a predisposing genotype. That is, 33% of patients had IO and 5% HIO.

Steatosis by MRI was studied in 79/132 patients: steatosis was present in 27 patients (34.17%) and 52 patients have not liver steatosis (65.82%).

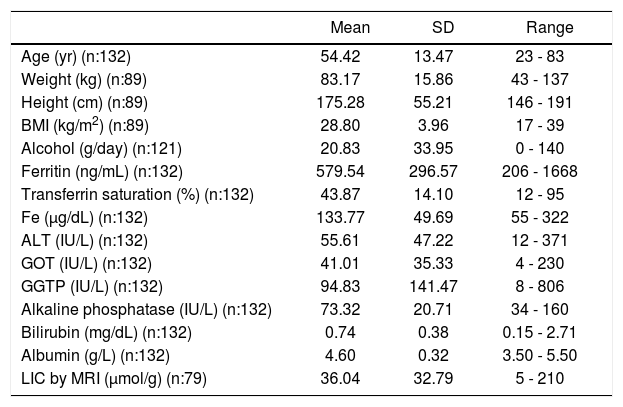

Clinical and Laboratory dataThe main clinical and laboratory data are presented in tables 1-3. Overall, 43/89 patients (48.31%) were classified as overweight (BMI 25-229.9), 36/89 (40.44%) as obese (BMI ≥ 30), and 10/89 (11.23%) as normal (< 25), meaning that 89% were overweight or obese.

Clinical baseline data, laboratory data and liver iron concentration (LIC) results obtained by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patients included in the study.

| Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) (n:132) | 54.42 | 13.47 | 23 - 83 |

| Weight (kg) (n:89) | 83.17 | 15.86 | 43 - 137 |

| Height (cm) (n:89) | 175.28 | 55.21 | 146 - 191 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (n:89) | 28.80 | 3.96 | 17 - 39 |

| Alcohol (g/day) (n:121) | 20.83 | 33.95 | 0 - 140 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) (n:132) | 579.54 | 296.57 | 206 - 1668 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) (n:132) | 43.87 | 14.10 | 12 - 95 |

| Fe (µg/dL) (n:132) | 133.77 | 49.69 | 55 - 322 |

| ALT (IU/L) (n:132) | 55.61 | 47.22 | 12 - 371 |

| GOT (IU/L) (n:132) | 41.01 | 35.33 | 4 - 230 |

| GGTP (IU/L) (n:132) | 94.83 | 141.47 | 8 - 806 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) (n:132) | 73.32 | 20.71 | 34 - 160 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) (n:132) | 0.74 | 0.38 | 0.15 - 2.71 |

| Albumin (g/L) (n:132) | 4.60 | 0.32 | 3.50 - 5.50 |

| LIC by MRI (µmol/g) (n:79) | 36.04 | 32.79 | 5 - 210 |

n: number of patients for each variable.

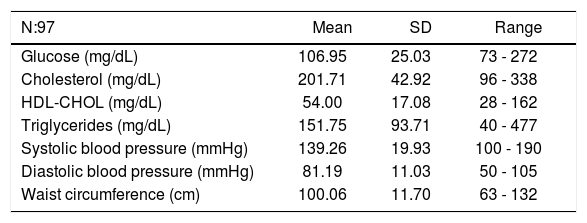

Laboratory data and clinical data for metabolic syndrome.

| N:97 | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 106.95 | 25.03 | 73 - 272 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 201.71 | 42.92 | 96 - 338 |

| HDL-CHOL (mg/dL) | 54.00 | 17.08 | 28 - 162 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 151.75 | 93.71 | 40 - 477 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 139.26 | 19.93 | 100 - 190 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 81.19 | 11.03 | 50 - 105 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 100.06 | 11.70 | 63 - 132 |

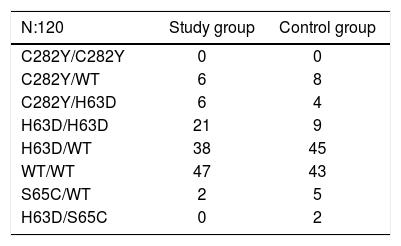

HFE gene mutations in Basque patients from the study group and the control group.7

| N:120 | Study group | Control group |

|---|---|---|

| C282Y/C282Y | 0 | 0 |

| C282Y/WT | 6 | 8 |

| C282Y/H63D | 6 | 4 |

| H63D/H63D | 21 | 9 |

| H63D/WT | 38 | 45 |

| WT/WT | 47 | 43 |

| S65C/WT | 2 | 5 |

| H63D/S65C | 0 | 2 |

The percentage of obese patients was high, and we studied the MRI findings in this group: 16 from 36 obese patients were studied by MRI for iron and steatosis. The mean LIC of the group was 34.68 µmol/g (SD 27.72). Steatosis was present in 8 from 16 patients studied. Three patients from 8 without steatosis had an ultrasound that suggested steatosis, but there were no discordancy cases (ultrasound/ MRI) in the steatosis group.

The alcohol data (121 patients) revealed that 77 (63.6%) consumed none and 22 consumed ≥ 60 g of alcohol/day (18.1%). Applying a cut-off of > 40 g/day, 25.6% were considered drinkers. The mean consumption was 20.83 g of alcohol/day (SD: 33.95, 0-140).

Viral serology produced positive results in 6/132 patients (4.5%): for HBV in 2 cases (1.5%) and HB-sAg and HCV in 4 (3%).

A total of 50 patients were receiving treatment for hypertension and 35 for dyslipidaemia.

MS (13) was detected in 44/80 men (55%) and 10/ 17 women (59%), corresponding overall to 54/97 of the HF patients (55.67%).

No liver biopsies were taken during the study period.

HFE mutation analysisThis analysis was conducted in 120 patients. Mutations were found in 60.84% of cases in the study group (vs. 62.93% of the control group). The results are presented in table 3. The genotype frequency of the H63D/H63D mutation in cases was more than double that in controls (17.5 vs. 7.76%), while the allele frequency of the H63D mutation was also higher: 36 vs. 31% controls.7 These differences were significant (p < 0.05), that is, both genotype and allele frequencies were significantly higher in the HF group.

Predisposing genotypes for liver iron overload/ HH8 were found in 27/120 patients (22.5%), H63D/ H63D in 21 and C282Y/H63D in 6 cases. Twenty patients had TS > 45%, and LIC was measured by MRI in all but one case: in the H63D/H63D group, 7 patients had raised and 8 normal LIC values, while in the C282Y/H63D group, one patient was found to have raised and 3 normal LICs by MRI.

HFE mutation analysis in MSThis analysis was studied in 51 from 54 patients with MS. The results were: 2 C282Y/wt (3.92%), 11 H63D/H63D (21.56%), 15 H63D/wt (29.41%), 3 C282Y/H63D (5.88), 19 wt/wt (37.25%), and 1 S65C (1.96%). The genotype frequency of the H63D/H63D mutation in MS cases was significantly higher than in controls7 −21.56 vs. 7.76%− (p = 0.011); the H63D allelic frequency was 42.15% in MS group and 31% in controls (p = 0.027).

HFE and liver iron overloadTwenty-six patients were shown to have IO-HIO in the liver by MRI. Among these individuals, the HFE mutation analysis found: H63D/H63D in 8 cases; wt/wt, 7; H63D/wt, 7; S65C/wt, 2; C282Y/wt, 1; and C282Y/H63D, 1; that is, 9 of these 26 patients had predisposing genotypes.

When we analysed some special groups, namely the SF > 1,000 ng/L group, and HIO group we obtained the following results:

- •

SF > 1000 ng/L group: 12/132 patients (9%) had SF levels of > 1,000 ng/L. In this group, the genotypes were determined in 11 patients with the following results: H63D/wt in 5; wt/wt, 3; H63D/ H63D, 1; C282Y/ wt, 1; and S65C/wt, 1. Accordingly, it seems that there is no relationship between HFE gene mutations and SF > 1,000 ng/L. Further, LIC was obtained by MRI in 10/12 of the patients in the high ferritin (> 1,000 ng/L) group. The LIC was raised (> 36 µmol/g), corresponding to IO, in 8/10 (80%) of these patients, while 2 had HIO.

- •

HIO group: overall, four patients had LICs of > 80 µmol/g, and their genetic findings were: H63D/wt in 2; C282Y/H63D in 1; and H63D/ H63D in 1; that is, 50% of these patients had predisposing genotypes. The C282y/H63D patient consumed no alcohol and had neither steatosis nor MS. One H63D patient drunk more than 80 g alcohol/day and presented steatosis; while the other patient with H63D, drank no alcohol and steatosis was not observed. Lastly, the H63D/ H63D patient drunk more than 80 g/day but did not have steatosis.

HF is a frequent finding in primary care when conducting routine laboratory studies. Patients with raised SF are referred to gastroenterology-hepatology units to study the relevance of this clinical entity.1–5,15,16 Recently, Adams and Barton17 have published an article stating that no more than 10% of these HF patients have liver iron overload. In a retrospective study, Yenson, et al.5reported an even lower rate of 5% of liver IO in Chinese and other Asian populations in British Columbia, Canada. Several studies have focused on analysing the causes of high or very high HF,18–21 but very few have explored the aetiology of patients referred for HF.1–3,5,16

Wong and Adams,1 in a retrospective series of 119 patients, found that in non-C282Y homozygotes with SF > 1,000 ng/L, IO was absent in 64% of the patients. Analysing this situation in the patients included in our study, 80% of those with a raised SF > 1,000 ng/L (12 patients) were found to have IO. Dever, et al.2reviewed the clinical charts of patients with HF referred to an IO Clinic in the USA: 51% of the subjects were diagnosed with HH. The results of that study are, however, influenced by the mixed characteristics of subjects included (not only those referred for HF, but also some with known HH and their relatives) and hence are not useful for comparison with our data. In Italy, Licata, et al.3 studied the presence of hepatic siderosis in liver biopsies of 54 patients, finding it in 17 (32%) of cases. Perez Aguilar, et al.15 in Valencia, Spain, studied the presence of iron in liver biopsies of 14 patients with SF > 1,000 ng/L, but for this series no quantitative measurements were reported. In our study group, as many as 33% of patients were found to have liver iron overload by a validated method using MRI.9–11 And more importantly, overall 5% of the patients showed high liver iron overload (> 80 µmo1/g), like HH patients.

Wong, et al.1 reported that 71% of the patients with raised LIC had a TSI > 50%. In our series, > 50% patients had raised TSI in the IO-HIO group.

In the Basque Country, the prevalence of HFE gene mutations in HH and the general population differs from other populations in Europe and elsewhere across the world.7 In the HH group, only 57% of patients had the C282Y/C282Y mutation, while the H63D mutation is very prevalent even in the general population, with a frequency > 30%.

There is evidence of the H63D mutation contributing to iron overload, increasing serum iron and transferrin, and also that its relationship with HH is independent of the presence of the C282Y mutation.8,21 In a control group,7 the H63D allele frequency was 31%. In this study of patients referred for HF, 61% presented mutations in the HFE gene, similar to the rate in controls (63%). The allele frequency was 36 vs. 31% in the control group, and the genotype frequency of the H63D/H63D mutation was 17.5%, compared to only 7.75% in the control group (both p < 0.05). This implies that rate of HF patients with this genotype is more than double that in the general population. Our results are consistent with the suggestion that this genotype could be responsible for HF.22,23

In a previous study by Aguilar-Martinez, et al.,23 the frequency of the H63D homozygous genotype was found to be higher among patients who had been referred with a personal or family history of IO than in the general population. The causative role of the H63D/H63D mutation in HH or IO has been demonstrated,22–24 but with less penetrance and a considerable variation in phenotypic expression.23 Assessing the relevance of HFE mutations in our HIO and IO groups, no significant differences were encountered. Further, no HFE genotype differences were seen when studying the SF > 1,000 ng/L group.

Clinical studies suggest that there are differences in iron metabolism and liver diseases between men and women.25 Consistent with this, in our series, there was a male/female sex ratio among patients of 4:1. Viral causes (4.5%) were not found to be significant as the factor underlying HF in our group, unlike in other populations, such as Asians, in whom viral hepatitis is more prevalent (17%) in HF patients.5 In other studies, the viral prevalence of the hepatitis C virus has varied from 3 to 42.7%.1–3

Patients with a history of chronic alcohol consumption or features of MS often present with hyperferritinemia.6 Heavy drinking (> 60 g/day of alcohol) was detected as a cause,8,13 in 18% of the population studied (25.6% if considering a cut-off of > 40 g/day). Overweight (BMI: 25-29.9) and obesity (BMI > 30), however, emerge as the most important causes of this entity: 89% of the patients were overweight or obese at the time of HF diagnosis. The obese patients presented a LIC by MRI of 34.68 µmol/g, not different from that of the whole study group, and 50% revealed fat in their livers, steatosis. Further, liver ultrasound revealed signs of steatosis, with suspicion of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, in 52% of the patients. When we studied for the presence of fat in the liver by MRI, steatosis was present in 34.17% of the 79 studied patients. MS is present in 25% of adults in Western countries, and HF is found in only 15% of MS patients.26–30 In a recent study for detection of HH and biochemical iron overload in primary care, developed in Spain, 45% of patients with elevated iron measures (TSI and/or SF) had MS.31 Notably, in our study, 56% of patients with HF met the criteria for MS. Considering the high percentage of H63D mutation in the population, we have studied HFE mutations in MS group, to determine if these mutations predispose to MS. The H63D/H63D mutation in MS cases was significantly higher than in controls7 −21.56 vs. 7.76%− (p = 0.011) and the H63D allelic frequency was 42.15% in the MS group and 31% in controls (p = 0.027). These results point out that H63D/H63D genotype and H63D allele predispose the patients with HF to develop a MS.

Analyzing the high SF group, we found no relationship between HFE gene mutations and SF > 1,000 ng/L. Of 12 patients with high SF, LIC was determined by MRI in 10. The LIC was raised in 8 of these 10 patients (80%), indicating that they had IO.

ConclusionIn conclusion, we can say from this study that the H63D/H63D genotype predisposes to HF. Obesity and overweight are very important etiological factors, affecting 89% of our HF patients. In our region, alcohol may be a cause of HF but viruses were rare as an underlying factor. Not all HF represents iron overload6 but MRI revealed iron overload in 33% of the patients. MS is present in 56% of the patients and may be induced by H63D/H63D genotype and H63D allele.

Abbreviations- •

BMI: body mass index.

- •

Fe: iron.

- •

HF: hyperferritinemia.

- •

HH: hereditary hemochromatosis.

- •

HIO: high iron overload.

- •

IO: iron overload.

- •

LIC: liver iron concentration.

- •

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

- •

MS: metabolic syndrome.

- •

SF: ferritin.

- •

TSI: transferrin saturation.

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Author’a ContributionsAll authors met the criteria for authorship as stablished by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. The manuscript represents honest work and all authors are able to verify the validity of the results reported.

Congress: presented as abstract at the Liver International meeting (EASL) 2012; Barcelona, Spain, April 18-22/ 2012.

AcknowledgementThe authors thank the translation department of the Instituto Vasco de Investigaciones Sanitarias (BIOEF) for their help.