Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are important for comprehensive assessment of chronic liver disease (CLD). Latin America and the Caribbean have a high burden of CLD, but PROs are lacking. We assessed health-related quality of life (HRQL) in Cuban patients with compensated CLD.

Materials and methodsA cross sectional study performed of adult patients with a diagnosis of chronic viral infection B and C (HBV, HCV), non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD) and autoimmune liver diseases (AILD) including autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and overlap syndrome (AIH+PBC). PROs were collected using: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F), Work Productivity and Activity-Specific Health Problem (WPAI: SHP), and the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ)-disease-specific.

Results543 patients enrolled, n=91 (HBV), n=188 (HCV), n=221 (NAFLD), n=43 (AILD). Of those with AILD, 22 had AIH, 14 PBC, and 7 overlap AIH/PBC. Mean age was 53.5 years, 64.1% female, 69.2% white, and 58.0% employed. Patients with HCV and AILD had more severe liver disease. A significant impairment in PROs was observed in HCV group whereas the AILD patients had more activity impairment. CLDQ-HRQL scores were significantly lower for patients with NAFLD and AILD compared to HBV. Male gender and exercising ≥90min/week predicted better HRQL. The strongest independent predictors of HRQL impairment were fatigue, abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression (p<0.05).

ConclusionsHRQL for Cuban patients with compensated CLD differs according to the CLD etiology. Patients with HCV and AILD had the worst PRO scores most likely related to severe underlying liver disease and/or extrahepatic manifestations.

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) is defined as any report about the status of a patient's health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient's response by a clinician or anyone else [1]. This concept is important because evidence suggest that clinicians’ understanding of the impact of a disease on patients’ daily lives tends to differ from patients’ points of view [2]. The use of measurements of PROs in everyday practice has the potential to narrow the gap between the clinician and patient's perspectives and help to tailor treatment plans to meet the patients’ preferences and needs [3]. In fact, it is believed that PRO assessment in clinical practice could provide more accurate detection of physical and psychological problems that may not be readily detected by routine clinical encounter. Additionally, PRO assessment can facilitate better monitoring of the disease progression and establishment of a common understanding which would strengthen patients’ adherence to prescribed treatment and contribute to shared decision-making between patients and providers [4]. However, despite the increasing consensus about the importance of capturing PROs from real-world clinical practices, data for patients with CLD are quite limited.

Liver disease is a worldwide health problem that accounts for approximately 2 million deaths per year. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cirrhosis was the 11th leading cause of death in 2016 accounting for 1,254,000 deaths in that year [5]. Latin America and the Caribbean region have a high percentage of deaths due to liver disease [6]. Additionally, cirrhosis is within the top 20 causes of the worldwide burden accounting for 1.7% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and 2.3% of years of life lost (YLL) [7].

There is growing evidence supporting severe impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and other PROs in patients with chronic liver disease (CLD). Patients with chronic liver disease suffer from fatigue, anxiety, depression, work productivity impairment and other emotional problems that greatly impair their HRQL [8]. In addition to significant clinical and PRO burden, patients with CLD require high cost health care resources representing an important economic burden for the society [9].

Measurement tools used to assess PROs in patients with CLD have provided an excellent insight into the PRO burden of CLD and its treatment from the patients’ perspective and, thus, are an important part of health care workers’ interaction with patients. Work continues to better understand the impact of different types of liver disease on PROs and their utility in clinical practice when formulating treatment plans [10].

In Cuba, cirrhosis and CLD have been the ninth leading cause of death since 2018 [11]. Given that several economic, political, cultural, geographical, and spiritual factors may affect HRQL and well-being, it is important to cover the current knowledge gap regarding the PROs in CLD patients from the Caribbean [12,13]. Therefore, the aims of this study were to assess the HRQL and other PROs in Cuban patients with chronic liver diseases (CLD) seen in real-world practice, to assess whether HRQL scores differ by the etiology of liver disease, and to determine which factors strongly impact PRO impairment.

2Methods2.1Study design and settingA cross sectional study was performed in adult patients with a well-documented diagnosis of chronic viral infection B and C (HBV, HCV), non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD), or autoimmune liver diseases (AILD) including autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and overlap syndrome (AIH+PBC) without decompensation. Patients were continuously enrolled from June 2018 to December 2019 at a single tertiary care academic center (National Institute of Gastroenterology, Havana, Cuba). The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IGE – 2018-04).

2.2ParticipantsThe primary inclusion criteria for viral hepatitis were the presence of viral hepatitis based on serology using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and confirmed using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to quantify viral load (HCV RNA and HBV DNA). Positive hepatitis C antibodies with a detectable level of HCV RNA were required for HCV. The diagnosis of chronic HBV was based on the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen with or without HBV DNA. NAFLD subjects were required to have established hepatic steatosis by historical liver biopsy or imaging technique and lack secondary causes of hepatic fat accumulation to include heavy alcohol use as described below [14]. All diagnoses of AIH, PBC and overlap syndrome were well documented and/or liver-biopsy proven.

Initial screening excluded patients with a diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, current or recent alcohol or drug abuse history, use of potentially hepatotoxic drugs, history of ischemic liver disease, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, hemochromatosis or Wilson's disease. Also, patients with history of decompensated cirrhosis (variceal hemorrhage, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, jaundice (total bilirubin level greater than 1.3 times the upper limit of normal), low serum albumin concentration (<35g/L), or prolonged prothrombin time (>15s or international normalized ratio >1.5), hepatocellular carcinoma, creatinine clearance less than 30mL/min, platelet count less than 100,000IU/μL, body mass index less than 18kg/m2, liver transplant, recent surgery, history of malignancy within 5 years of screening, and/or with another active chronic medical or psychiatric condition, as well as those unable to communicate and/or fill questionnaires or who declined to participate were excluded. We chose to exclude patients with decompensated liver disease to avoid the confounding influence of decompensation on patient's reported HRQL [15].

During an office visit, after giving informed consent, patients completed self-administered HRQL questionnaires. Demographics, personal habits, medical history and clinical data were also collected from patients as self-reported. Data were entered by clinical personnel to clinical charts; for the purpose of this study, all medical records of interest were detailed in a pre-approved data collection form.

2.3Data sources/measurement2.3.1Patient-reported outcomesPatient-reported outcomes were collected using validated PROs instruments: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F), Work Productivity and Activity - Specific Health Problem (WPAI: SHP), and disease-specific versions of the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ or CLDQ-HCV) [16–22]. These PRO instruments were self-administered by patients at their initial visit to the clinic prior to initiation of communication with their healthcare provider. Suggested recall period was between 1 and 4 weeks depending on the instrument. The Spanish version of Puerto Rico (Northwest's Translation, Inc.), as the closest language-equivalent version, of all PROs instruments was used with linguistic validation for the use in Cuba. Cultural adaptation was made by expert panel of the Faculty of Arts and Letters, University of Havana and the Cuban Academy of Language. The panel reviewed the linguistic relevance and suitability of all the questionnaires in the Spanish version of Puerto Rico for applying to Cuban patients. A pilot test was done for the questionnaires in 30 patients, and the internal consistency assessment returned Cronbach's alpha coefficients for CLDQ, CLDQ-HCV, FACIT-F of 0.92, 0.91, and 0.82, respectively.

The FACIT-F is a PRO instrument which includes a generic FACIT core component with four domains (Physical, Emotional, Social, and Functional Well-Being) and a fatigue-specific domain (Fatigue Scale). All domains are designed to indicate better health status with greater scores, and all add up to the total FACIT-F score which ranges from 0 to 160 [16–18].

The WPAI:SHP instrument evaluated the impairment in daily activities and in work associated with a specific health problem (in this study, CLD). It included Work Productivity Impairment domain, which is a sum of Absenteeism and Presenteeism scores (all collected from employed patients only), and Activity Impairment domain, which quantifies impairment in daily activities other than work. In WPAI, all scores range from 0 to 1 and a score of 0 indicates no impairment while a score of 1 indicates complete inability to do work or activities [19].

The CLDQ is a disease-specific PRO instrument developed for assessment of HRQL in patients with CLD; in this study, it was completed by HBV, AILD, and NAFLD patients [19]. The CLDQ have six PRO domains (Abdominal Symptoms, Activity, Emotional, Fatigue, Systemic Symptoms, Worry). In addition, patients with HCV completed CLDQ-HCV which is a HCV-specific HRQL instrument that was specifically designed and validated to assess HRQL in HCV-infected patients. The CLDQ-HCV has four PRO domains (Activity, Emotional, Systemic Symptoms, Worry) [21,22]. In all CLDQ instruments, all PRO domains range 1–7 with higher values representing better HRQL.

2.3.2Clinical and demographic parametersCollected demographics included age, gender, race (reported according to the national office of statistics for Cuba based on the color of skin: white, black and mestizo) [23]. The employment status was collected from the respective item on the WPAI:SHP.

Personal habits recorded included: current smoking (regular or occasional use of tobacco products), the practice of exercise (>90min/week), and current alcohol use defined as the amount of alcohol consumed on a daily basis over the past six months. Heavy alcohol use was defined as more than 4 drinks on any day for men or more than 3 drinks for women, following the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines where one “standard” drink was equivalent to 1 regular beer, or 12oz of liquor or 5oz of wine or 1 shot of distilled spirit (https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/what-standard-drink). Social drinker or abstinece was assigned to those who either drank alcohol but did not meet the NIAAA guidelines for being a heavy drink or reported that they did not drink alcohol at all, respectively [24].

Medical history was collected using a pre-approved data collection form which included the measurements of weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) [25]. The laboratory tests included platelet count, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). Blood levels of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus were quantified using a COBAS AMPLICOR® version 2.0 (Roche, Switzerland), serology was measured using ELISA.

At the time of enrollment, the results of upper abdominal ultrasounds (Toshiba Aplio 300, Toshiba Medical Systems Europe, The Netherlands) were reviewed. The presence of advanced fibrosis (cirrhosis) was established using historic liver biopsy or, if unavailable, using transient elastography >12kPa (Fibroscan 404, Echosens, Paris, France). The AST to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) and Fibrosis-4 score (FIB-4) were also calculated for each patient [26].

2.4Statistical analysisClinico-demographic parameters and PROs were summarized as frequency (percentage) or mean±standard deviation by CLD etiology and were compared across the etiologies using Chi-square test (for binary parameters such as cirrhosis) or Mann–Whitney test (for continuous or pseudo-continuous parameters such as age or PRO scores).

Independent predictors of PRO scores in patients with CLD were assessed in a series of multiple regression models with bidirectional stepwise selection of clinico-demographic parameters; only predictors with p<0.05 were left in the final models except for the CLD etiologies which were forced in the models regardless of statistical significance.

All analyses were run in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P values were carried to four decimal places where applicable and two places when feasible.

3ResultsOf 1663 patients who attended the clinics during the study period, 548 met the eligibility criteria and 543 (99%) completed all questionnaires and clinical data; the remaining 1125 patients did not meet the inclusion criteria, had insufficient medical records, or were unable to provide informed consent. Of the 543 patients enrolled, n=91 had HBV (75 on antiviral treatment, 12 without detectable viremia), n=188 had HCV, and n=221 had NAFLD; an additional n=43 from the AILD group included 22 with AIH, 14 with PBC, and 7 with overlap of AIH and PBC.

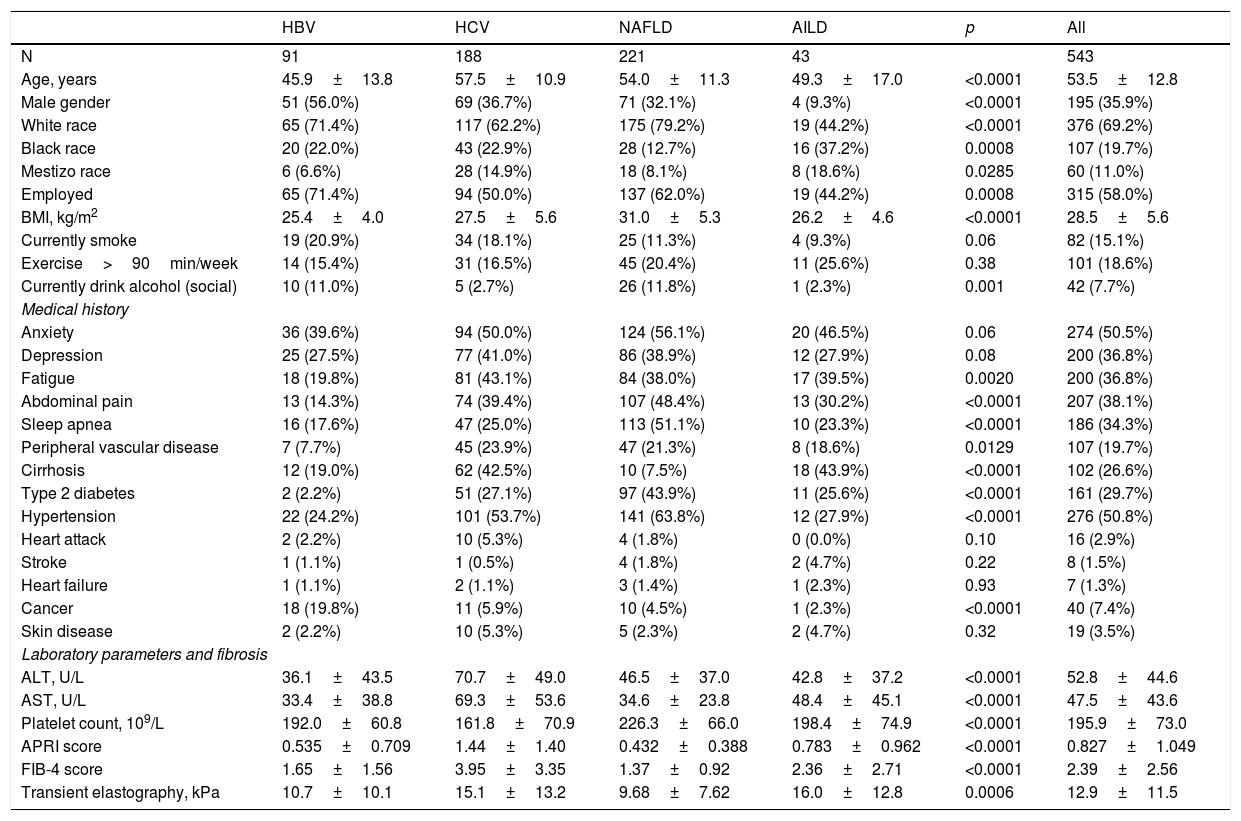

The demographics and clinical data of patients with CLD by etiology are summarized in Table 1.

Demographics and clinical parameters of patients with chronic liver disease by etiology.

| HBV | HCV | NAFLD | AILD | p | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 91 | 188 | 221 | 43 | 543 | |

| Age, years | 45.9±13.8 | 57.5±10.9 | 54.0±11.3 | 49.3±17.0 | <0.0001 | 53.5±12.8 |

| Male gender | 51 (56.0%) | 69 (36.7%) | 71 (32.1%) | 4 (9.3%) | <0.0001 | 195 (35.9%) |

| White race | 65 (71.4%) | 117 (62.2%) | 175 (79.2%) | 19 (44.2%) | <0.0001 | 376 (69.2%) |

| Black race | 20 (22.0%) | 43 (22.9%) | 28 (12.7%) | 16 (37.2%) | 0.0008 | 107 (19.7%) |

| Mestizo race | 6 (6.6%) | 28 (14.9%) | 18 (8.1%) | 8 (18.6%) | 0.0285 | 60 (11.0%) |

| Employed | 65 (71.4%) | 94 (50.0%) | 137 (62.0%) | 19 (44.2%) | 0.0008 | 315 (58.0%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.4±4.0 | 27.5±5.6 | 31.0±5.3 | 26.2±4.6 | <0.0001 | 28.5±5.6 |

| Currently smoke | 19 (20.9%) | 34 (18.1%) | 25 (11.3%) | 4 (9.3%) | 0.06 | 82 (15.1%) |

| Exercise>90min/week | 14 (15.4%) | 31 (16.5%) | 45 (20.4%) | 11 (25.6%) | 0.38 | 101 (18.6%) |

| Currently drink alcohol (social) | 10 (11.0%) | 5 (2.7%) | 26 (11.8%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0.001 | 42 (7.7%) |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Anxiety | 36 (39.6%) | 94 (50.0%) | 124 (56.1%) | 20 (46.5%) | 0.06 | 274 (50.5%) |

| Depression | 25 (27.5%) | 77 (41.0%) | 86 (38.9%) | 12 (27.9%) | 0.08 | 200 (36.8%) |

| Fatigue | 18 (19.8%) | 81 (43.1%) | 84 (38.0%) | 17 (39.5%) | 0.0020 | 200 (36.8%) |

| Abdominal pain | 13 (14.3%) | 74 (39.4%) | 107 (48.4%) | 13 (30.2%) | <0.0001 | 207 (38.1%) |

| Sleep apnea | 16 (17.6%) | 47 (25.0%) | 113 (51.1%) | 10 (23.3%) | <0.0001 | 186 (34.3%) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 7 (7.7%) | 45 (23.9%) | 47 (21.3%) | 8 (18.6%) | 0.0129 | 107 (19.7%) |

| Cirrhosis | 12 (19.0%) | 62 (42.5%) | 10 (7.5%) | 18 (43.9%) | <0.0001 | 102 (26.6%) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2 (2.2%) | 51 (27.1%) | 97 (43.9%) | 11 (25.6%) | <0.0001 | 161 (29.7%) |

| Hypertension | 22 (24.2%) | 101 (53.7%) | 141 (63.8%) | 12 (27.9%) | <0.0001 | 276 (50.8%) |

| Heart attack | 2 (2.2%) | 10 (5.3%) | 4 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.10 | 16 (2.9%) |

| Stroke | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (0.5%) | 4 (1.8%) | 2 (4.7%) | 0.22 | 8 (1.5%) |

| Heart failure | 1 (1.1%) | 2 (1.1%) | 3 (1.4%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0.93 | 7 (1.3%) |

| Cancer | 18 (19.8%) | 11 (5.9%) | 10 (4.5%) | 1 (2.3%) | <0.0001 | 40 (7.4%) |

| Skin disease | 2 (2.2%) | 10 (5.3%) | 5 (2.3%) | 2 (4.7%) | 0.32 | 19 (3.5%) |

| Laboratory parameters and fibrosis | ||||||

| ALT, U/L | 36.1±43.5 | 70.7±49.0 | 46.5±37.0 | 42.8±37.2 | <0.0001 | 52.8±44.6 |

| AST, U/L | 33.4±38.8 | 69.3±53.6 | 34.6±23.8 | 48.4±45.1 | <0.0001 | 47.5±43.6 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 192.0±60.8 | 161.8±70.9 | 226.3±66.0 | 198.4±74.9 | <0.0001 | 195.9±73.0 |

| APRI score | 0.535±0.709 | 1.44±1.40 | 0.432±0.388 | 0.783±0.962 | <0.0001 | 0.827±1.049 |

| FIB-4 score | 1.65±1.56 | 3.95±3.35 | 1.37±0.92 | 2.36±2.71 | <0.0001 | 2.39±2.56 |

| Transient elastography, kPa | 10.7±10.1 | 15.1±13.2 | 9.68±7.62 | 16.0±12.8 | 0.0006 | 12.9±11.5 |

AILD: autoimmune liver diseases, ALT: alanine aminotransferase AST: aspartate aminotransferase, BMI: body mass index, HBV: hepatitis B virus HCV: hepatitis C virus, NAFLD: non-alcoholic liver disease.

Patients included were, on average, 53.5 years of age, 64.1% female, 69.2% white, 58.0% employed, with mean (SD) BMI of 28.5±5.6kg/m2. The HBV group was the youngest (mean age 45.9) with the most men (56%). Personal habits like smoking and practice of exercise did not differ among groups while social drinkers were the most common in NAFLD and HBV (Table 1).

Psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety (50.5%), depression (36.8%) and fatigue (36.8%) were common across all CLD groups; although patients with HBV had the lowest rates of all three conditions (Table 1). Abdominal pain was reported by 38.1% of all patients but was as high as 48.4% in NAFLD patients. Similarly, sleep apnea (51.1%), diabetes (43.9%) and hypertension (63.8%) were the most common in NAFLD in comparison to other studied etiologies of CLD (Table 1).

Patients with HCV and AILD had more severe liver disease, both histology- or non-invasive tests such as imaging and higher scores for APRI and FIB-4 (Table 1).

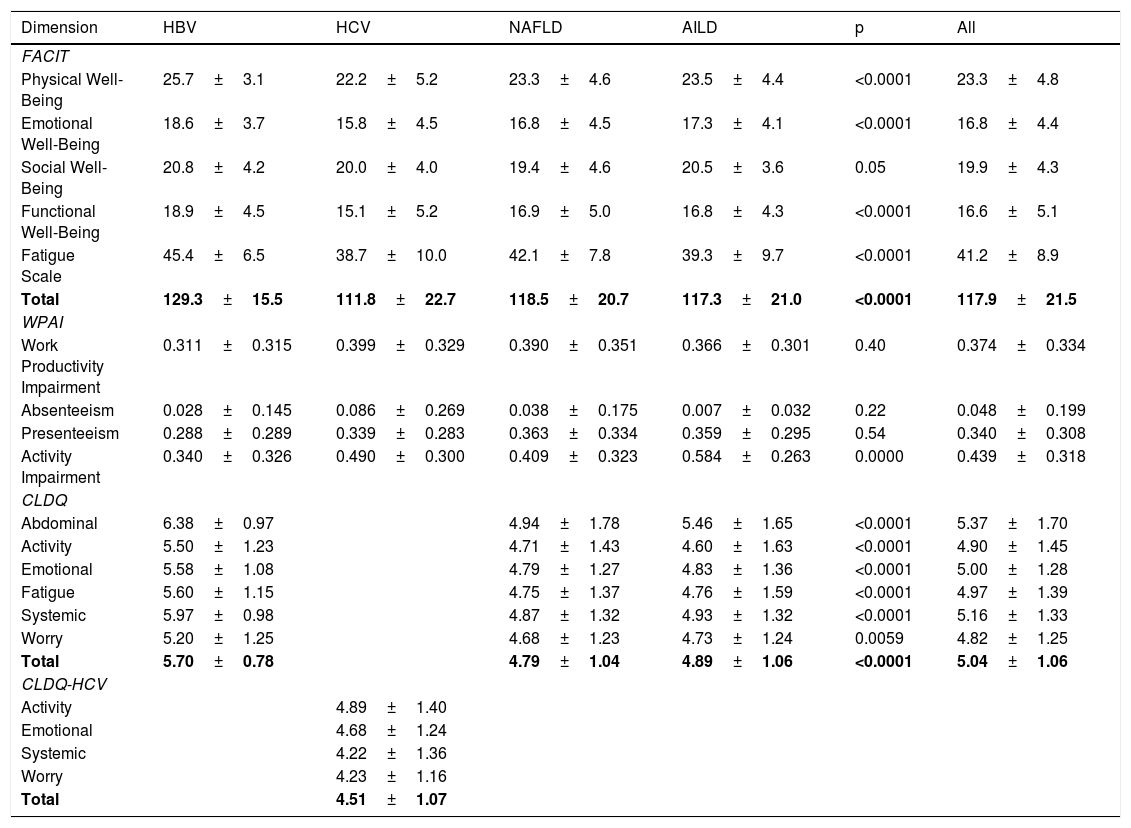

PRO scores for FACIT-F, CLDQ/CLDQ-HCV, and WPAI instruments for different etiologies of CLD are displayed in Table 2. Across all patients with CLD, there was a notable impairment in FACIT-F scores observed in HCV patients whereas HBV patients had the highest scores (Table 2). On the other hand, the measurements of WPAI-SHP score were similar between groups for work productivity impairment, but the AILD group had more activity impairment followed by HCV (Table 2). Finally, HRQL measured by CLDQ was significantly lower in NAFLD and AILD patients compared with HBV. Among all domains of CLDQ, the activity domain had the lowest score (4.60±1.63) in AILD patients (Table 2). Similarly, analyzing HCV group with the disease-specific instrument CLDQ-HCV, we found the mean (SD) total score of 4.51±1.07, with the worst scores in the systemic and worry domains (Table 2).

HRQL (PRO scores) for patients with different types of chronic liver disease.

| Dimension | HBV | HCV | NAFLD | AILD | p | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACIT | ||||||

| Physical Well-Being | 25.7±3.1 | 22.2±5.2 | 23.3±4.6 | 23.5±4.4 | <0.0001 | 23.3±4.8 |

| Emotional Well-Being | 18.6±3.7 | 15.8±4.5 | 16.8±4.5 | 17.3±4.1 | <0.0001 | 16.8±4.4 |

| Social Well-Being | 20.8±4.2 | 20.0±4.0 | 19.4±4.6 | 20.5±3.6 | 0.05 | 19.9±4.3 |

| Functional Well-Being | 18.9±4.5 | 15.1±5.2 | 16.9±5.0 | 16.8±4.3 | <0.0001 | 16.6±5.1 |

| Fatigue Scale | 45.4±6.5 | 38.7±10.0 | 42.1±7.8 | 39.3±9.7 | <0.0001 | 41.2±8.9 |

| Total | 129.3±15.5 | 111.8±22.7 | 118.5±20.7 | 117.3±21.0 | <0.0001 | 117.9±21.5 |

| WPAI | ||||||

| Work Productivity Impairment | 0.311±0.315 | 0.399±0.329 | 0.390±0.351 | 0.366±0.301 | 0.40 | 0.374±0.334 |

| Absenteeism | 0.028±0.145 | 0.086±0.269 | 0.038±0.175 | 0.007±0.032 | 0.22 | 0.048±0.199 |

| Presenteeism | 0.288±0.289 | 0.339±0.283 | 0.363±0.334 | 0.359±0.295 | 0.54 | 0.340±0.308 |

| Activity Impairment | 0.340±0.326 | 0.490±0.300 | 0.409±0.323 | 0.584±0.263 | 0.0000 | 0.439±0.318 |

| CLDQ | ||||||

| Abdominal | 6.38±0.97 | 4.94±1.78 | 5.46±1.65 | <0.0001 | 5.37±1.70 | |

| Activity | 5.50±1.23 | 4.71±1.43 | 4.60±1.63 | <0.0001 | 4.90±1.45 | |

| Emotional | 5.58±1.08 | 4.79±1.27 | 4.83±1.36 | <0.0001 | 5.00±1.28 | |

| Fatigue | 5.60±1.15 | 4.75±1.37 | 4.76±1.59 | <0.0001 | 4.97±1.39 | |

| Systemic | 5.97±0.98 | 4.87±1.32 | 4.93±1.32 | <0.0001 | 5.16±1.33 | |

| Worry | 5.20±1.25 | 4.68±1.23 | 4.73±1.24 | 0.0059 | 4.82±1.25 | |

| Total | 5.70±0.78 | 4.79±1.04 | 4.89±1.06 | <0.0001 | 5.04±1.06 | |

| CLDQ-HCV | ||||||

| Activity | 4.89±1.40 | |||||

| Emotional | 4.68±1.24 | |||||

| Systemic | 4.22±1.36 | |||||

| Worry | 4.23±1.16 | |||||

| Total | 4.51±1.07 | |||||

Scale scores for FACIT-F range between 0 and 160, scale score for physical, social and functional well-being domains range between 0 a28, scale score for emotional well-being range 0–24.

WPAI:SHP all scale range between 0 and 1.

CLDQ scores for each domain range from 1 (most impairment) to 7 (least impairment). The overall CLDQ score also ranges from 1 to 7.

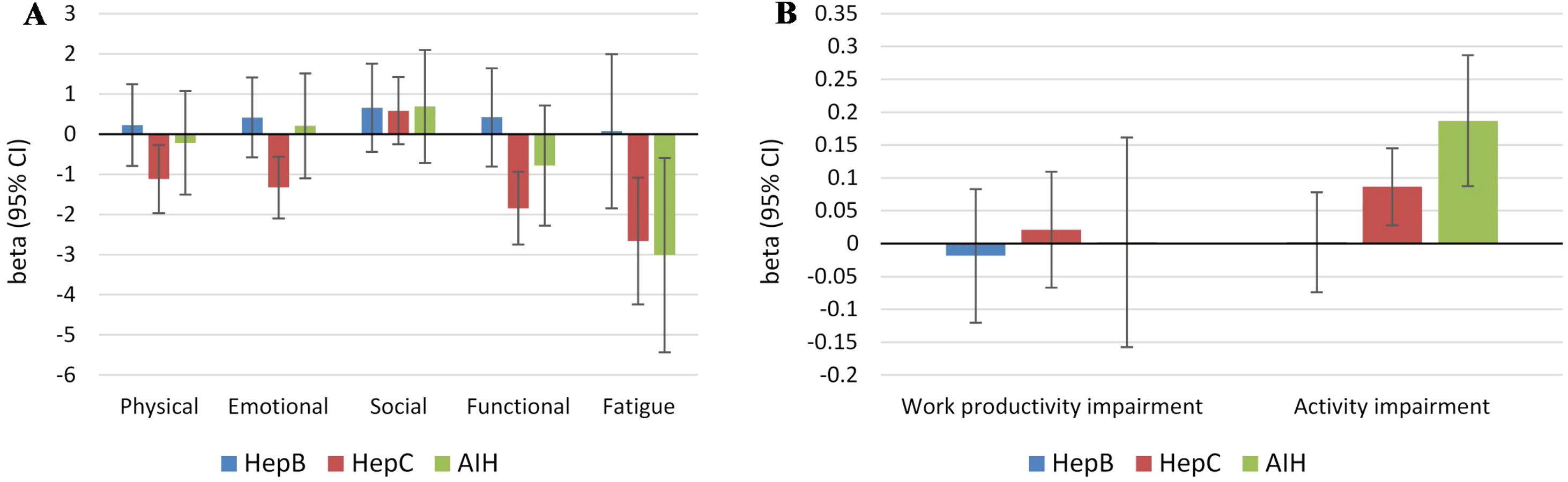

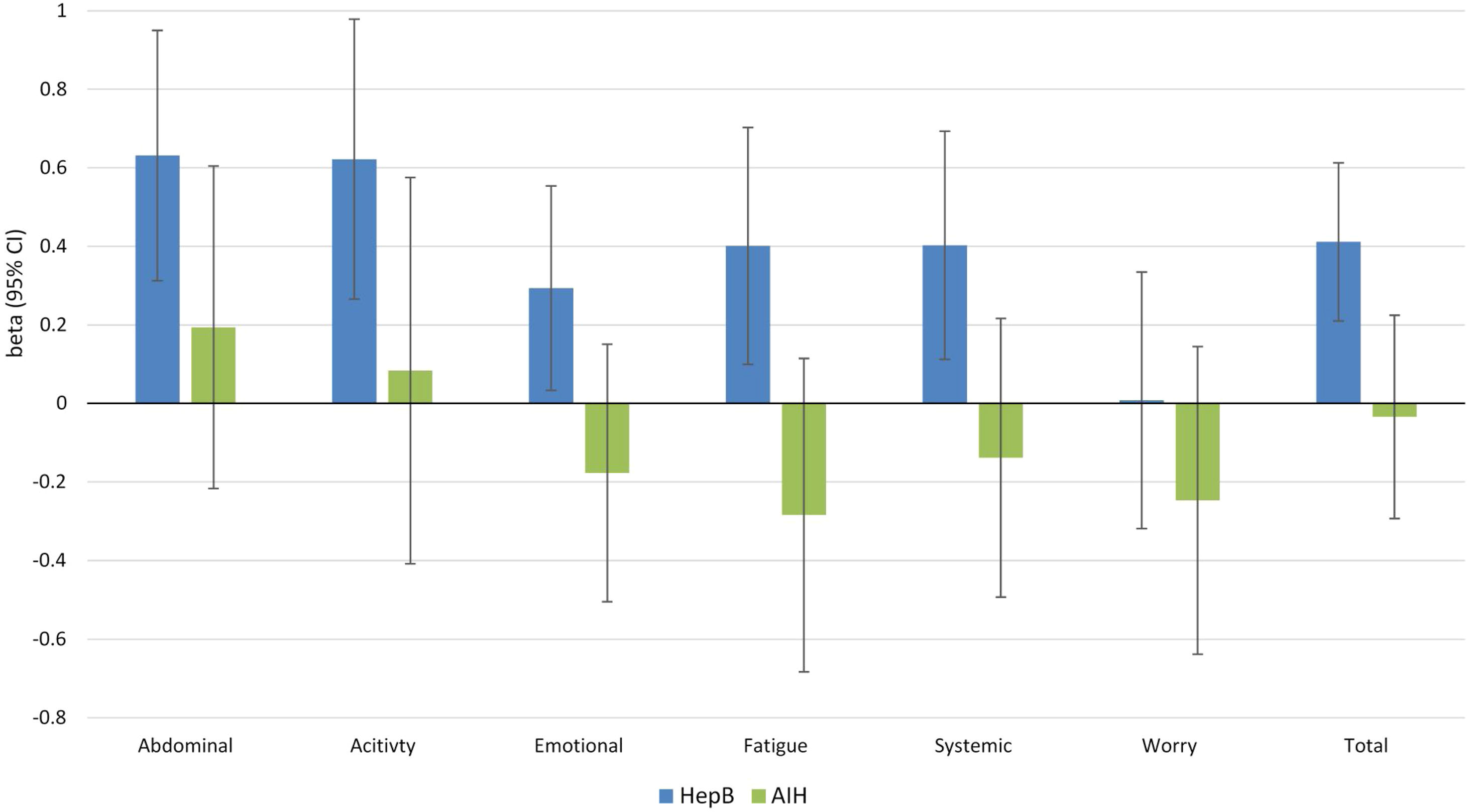

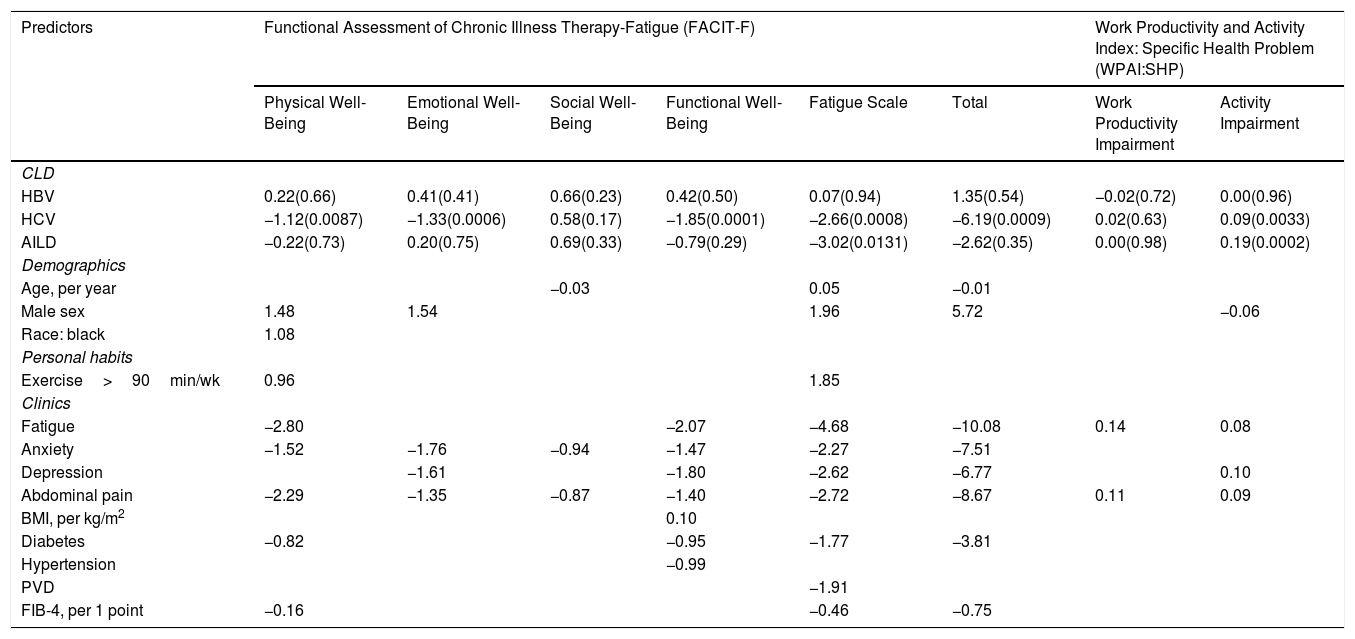

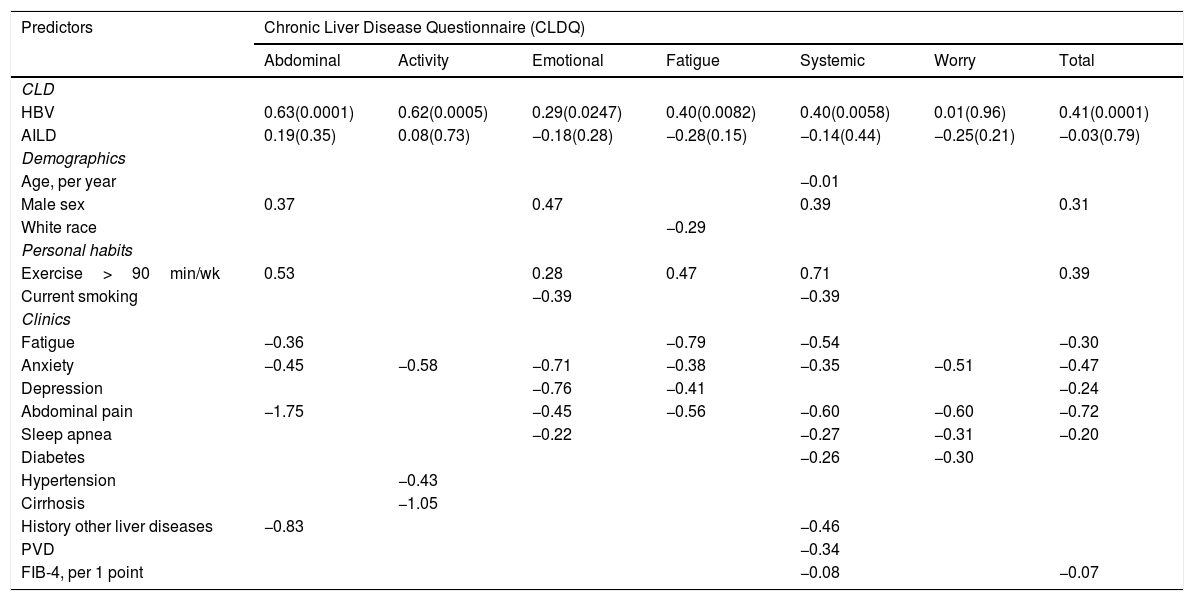

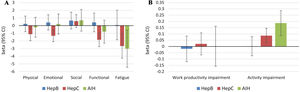

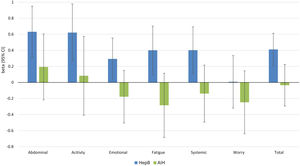

Independent predictors of PRO scores in CLD patients, presuming NAFLD to be the reference etiology, are displayed in Tables 3 and 4. As shown, among all CLD etiologies, HCV had the worst impact on HRQL: β=−6.19 for total FACIT-F score (p<0.001) (Table 3, Fig. 1). At the same time, having HBV was independently associated with the highest CLDQ scores (Fig. 2).

Main clinic demographics independent predictors of HRQL (PRO scores) in Patients with Different Types of Chronic Liver Disease (FACIT-F and WPAI: SHP instruments).

| Predictors | Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) | Work Productivity and Activity Index: Specific Health Problem (WPAI:SHP) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Well-Being | Emotional Well-Being | Social Well-Being | Functional Well-Being | Fatigue Scale | Total | Work Productivity Impairment | Activity Impairment | |

| CLD | ||||||||

| HBV | 0.22(0.66) | 0.41(0.41) | 0.66(0.23) | 0.42(0.50) | 0.07(0.94) | 1.35(0.54) | −0.02(0.72) | 0.00(0.96) |

| HCV | −1.12(0.0087) | −1.33(0.0006) | 0.58(0.17) | −1.85(0.0001) | −2.66(0.0008) | −6.19(0.0009) | 0.02(0.63) | 0.09(0.0033) |

| AILD | −0.22(0.73) | 0.20(0.75) | 0.69(0.33) | −0.79(0.29) | −3.02(0.0131) | −2.62(0.35) | 0.00(0.98) | 0.19(0.0002) |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age, per year | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.01 | |||||

| Male sex | 1.48 | 1.54 | 1.96 | 5.72 | −0.06 | |||

| Race: black | 1.08 | |||||||

| Personal habits | ||||||||

| Exercise>90min/wk | 0.96 | 1.85 | ||||||

| Clinics | ||||||||

| Fatigue | −2.80 | −2.07 | −4.68 | −10.08 | 0.14 | 0.08 | ||

| Anxiety | −1.52 | −1.76 | −0.94 | −1.47 | −2.27 | −7.51 | ||

| Depression | −1.61 | −1.80 | −2.62 | −6.77 | 0.10 | |||

| Abdominal pain | −2.29 | −1.35 | −0.87 | −1.40 | −2.72 | −8.67 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

| BMI, per kg/m2 | 0.10 | |||||||

| Diabetes | −0.82 | −0.95 | −1.77 | −3.81 | ||||

| Hypertension | −0.99 | |||||||

| PVD | −1.91 | |||||||

| FIB-4, per 1 point | −0.16 | −0.46 | −0.75 | |||||

Beta values are displayed in the table for each independent predictor of the PRO scores (p<0.05 only except for CLD etiology). Reference CLD etiology: NAFLD.

Clinic demographics independent predictors of HRQL (PRO scores) in CLD patients evaluated with CLDQ.

| Predictors | Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal | Activity | Emotional | Fatigue | Systemic | Worry | Total | |

| CLD | |||||||

| HBV | 0.63(0.0001) | 0.62(0.0005) | 0.29(0.0247) | 0.40(0.0082) | 0.40(0.0058) | 0.01(0.96) | 0.41(0.0001) |

| AILD | 0.19(0.35) | 0.08(0.73) | −0.18(0.28) | −0.28(0.15) | −0.14(0.44) | −0.25(0.21) | −0.03(0.79) |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, per year | −0.01 | ||||||

| Male sex | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.31 | |||

| White race | −0.29 | ||||||

| Personal habits | |||||||

| Exercise>90min/wk | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 0.71 | 0.39 | ||

| Current smoking | −0.39 | −0.39 | |||||

| Clinics | |||||||

| Fatigue | −0.36 | −0.79 | −0.54 | −0.30 | |||

| Anxiety | −0.45 | −0.58 | −0.71 | −0.38 | −0.35 | −0.51 | −0.47 |

| Depression | −0.76 | −0.41 | −0.24 | ||||

| Abdominal pain | −1.75 | −0.45 | −0.56 | −0.60 | −0.60 | −0.72 | |

| Sleep apnea | −0.22 | −0.27 | −0.31 | −0.20 | |||

| Diabetes | −0.26 | −0.30 | |||||

| Hypertension | −0.43 | ||||||

| Cirrhosis | −1.05 | ||||||

| History other liver diseases | −0.83 | −0.46 | |||||

| PVD | −0.34 | ||||||

| FIB-4, per 1 point | −0.08 | −0.07 | |||||

Independent predictors of PRO scores in CLD patients (p<0.05 only except for CLD etiology). Reference CLD etiology: NAFLD. Beta values are displayed in the table for each predictor.

Independent association of Chronic Liver Disease etiology with PRO scores measured by FACIT-F (A) and WPAI: SHP (B) (adjusted for clinic-demographic factors from Table 3).

Independent association of Chronic Liver Disease etiology with PRO scores measured by CLDQ (adjusted for clinic-demographic factors from Table 4).

Out of demographic factors, we found that male gender was a positive predictor of physical and emotional well-being, fatigue scale and the total HRQL score (FACIF-F), activity impairment (WPAI) (Table 3), and abdominal, emotional and systemic domains of CLDQ (Table 4). Additionally, exercising more than 90min/week was also a positive predictor of physical well-being and less fatigue (FACIT-F), as well as of higher scores in abdominal, emotional, fatigue and systemic domains of CLDQ (Table 4). There was no consistent association of PRO scores with age (all p>0.02).

Out of the clinical variables, the strongest independent predictors of HRQL impairment with clinically reported fatigue, abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression (Tables 3 and 4). Additionally, presence of type 2 diabetes and higher FIB-4 score had a negative impact on the total FACIT-F score (Table 3). Furthermore, the presence of clinically reported fatigue and abdominal pain predicted more impairment in work productivity and activity as determined by WPAI, while depression was associated with greater activity impairment (Table 3). All these predictors as well as sleep apnea were negatively associated with CLDQ scores (Table 4).

4DiscussionThis is the first study which assesses the HRQL impairment in Cuban patients with CLD who are seen in real-world practice. In this analysis, we found that HRQL in patients with HCV is much lower than in patients with other CLD etiologies. The reduced overall HRQL scores in these patients can be predicted best by presence of several symptoms such as fatigue, abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression. In contrast, male gender and exercising for more than 90min/week were predictors of a better HRQL, while age does not seem to influence the PRO scores. Furthermore, patients with more severe liver diseases had worse HRQL scores. In fact, PRO scores in HCV remained significantly lower even after adjustment for the above-mentioned factors, suggesting that there are other drivers of HRQL impairment for those with HCV.

Since the clinical characteristics of patients with different CLDs were dissimilar, we analyzed the HRQL data according to the etiology of CLD. In this context, most HBV patients were asymptomatic, inactive, untreated or immunotolerant, while some were being treated with nucleoside/nucleotide analogues without reporting adverse events. Meanwhile, patients with autoimmune disease had a long history of the disease with systemic manifestations and were receiving immunosuppressive treatment. On the other hand, most of the HCV patients had several years of infection with active viremia, and had previously been treated with interferon-based therapy without achieving sustained virologic response. At the time of enrollment, these patients were awaiting treatment with direct-acting antivirals. Therefore, not surprisingly, patients with HCV and AILD had more severe liver disease, interpreted as more fibrosis, and the worst HRQL.

Since NAFLD patients did not have a specific pharmacological treatment, they were considered as a reference group to compare with the other causes of CLD. Nevertheless, it is important to note that a recent systematic review demonstrated that NAFLD patients reported poor physical HRQL which has been associated with a variety of disease-related parameters, mostly the presence of fatigue [27]. Sleep apnea and abdominal pain were additionally more common in our NAFLD group and had a negative impact on their quality of life.

In regards to gender, our results suggest that female patients with CLD had more HRQL impairment, similar to that reported by other authors [28,29]. On the other hand, age was found to be responsible for only a small decrease in HRQL among all patient with CLD [29], and was not a consistent predictor of PRO scores in our multivariate analysis.

Together, these associations of gender, extrahepatic comorbidities, and severity of liver disease with PRO impairment validates these predictors reported from other HRQL studies are also important for Cuban patients with CLD seen in real-world practices [30–40]. As such, our understanding of the patient's perspective of their CLD continues to be validated and need to be considered when treating patients.

There are several limitations of this present study which must be considered. In this study, patients were recruited from the clinics of a tertiary referral center and therefore may not be a representation of all patients with CLD in the country. Nevertheless, the study was conducted under the conditions of real-world practice so these HRQL data may be better generalizable in comparison to commonly seen data coming from patients enrolled in clinical trials. Some patients were previously treated or were receiving medical treatment for CLD, therefore, a potential bias of PROs in our sample cannot be completely excluded. Another possible factor influencing HRQL are comorbidities and their medical treatment. In fact, reduced HRQL in patients that were administered a large quantity of drugs of various classes (e.g. analgesics, diuretics, antihypertensive and anti-diabetic) can provoke drug-related side effects. Patients could have more than one comorbid disease necessitating more daily medication treatments which could affect HRQL. However, we could not confirm this potential explanation as the pre-approved data collection protocol used in this study did not include the details of concomitant medication use so this source of bias could not be accounted for. Finally, unavailability of HRQL data from the general Cuban population does not provide a comparison group without liver disease; however, the use of valid instruments allows a more in-depth analysis of data in the national context and possible comparisons with other international realities.

Despite the above limitations, our data provides important validation of PRO data reported from outside Cuba and Caribbean countries [41,42]. Indeed, untreated HCV patients show significant impairment of HRQL. The prevalence of fatigue and other psychological issues, namely, depression and anxiety, is high in these patients and is likely the main driver of PRO impairment [40]. Additionally, uncertainty about the availability of the curative treatment may have aggravated psychological concerns in these patients with a negative impact on their PROs [43]. Our data are also interesting in showing better PROs in patients with HBV which is consistant with PRO reports from the rest of the world [44] Furthermore, assessment of HRQL in AIH demonstrated that anxiety and depression were also highly prevalent; however, these symptoms have been attributed to the use of a steroid-based therapy.[45,46] It is important to note that fatigue is a typical symptom in cholestatic liver diseases such as PBC which tends to get worse with disease severity and an expectedly negative impact on HRQL [47,48].

The most important aspect of the study is our integrated approach with the use of PROs in clinical practice using both generic and disease-specific instruments. This type of assessment allows for a comprehensive evaluation of important factors that can affect patients’ well-being which allowed us to provide a Cuban perspective about PROs in patients with CLD.

In conclusions, the HRQL of Cuban patients with compensated chronic liver diseases assessed in real-world practice differs according to the etiology of their liver disease. We found that HCV and AILD patients had the worst patient-reported outcome scores. These impairments in PROs were driven by severity of liver disease as well as co-morbid conditions such as clinically reported fatigue, abdominal pain, anxiety, depression, sleep apnea, and type 2 diabetes. In this context, it is not only important to treat the underlining causes of CLD but also to address these important underlying co-morbidities.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of InterestNone.

Authorship statementsMarlen I. Castellanos-Fernandez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision; Validation; Visualization and Writing – original draft, Susana A. Borges Gonzalez: Investigation; Methodology and Writing – original draft, Maria Stepanova: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology, Software; Visualization and writing – review editing. Mirtha E. Infante Velázquez, Caridad Ruenes Domech, Sila M. González Suero, Zaily Dorta Guridi and Enrique R. Arus Soler: Investigation; Resources and writing – review editing. Andrei Racila: Project administration; Resources; Software. Zobair M. Younossi: Supervision and writing – review editing.

The authors acknowledge Adrian H. Van-Nooten MD for correction of the manuscript language; the authors also thank Rosaura Pichs for given technical support and collaboration with health statistics.