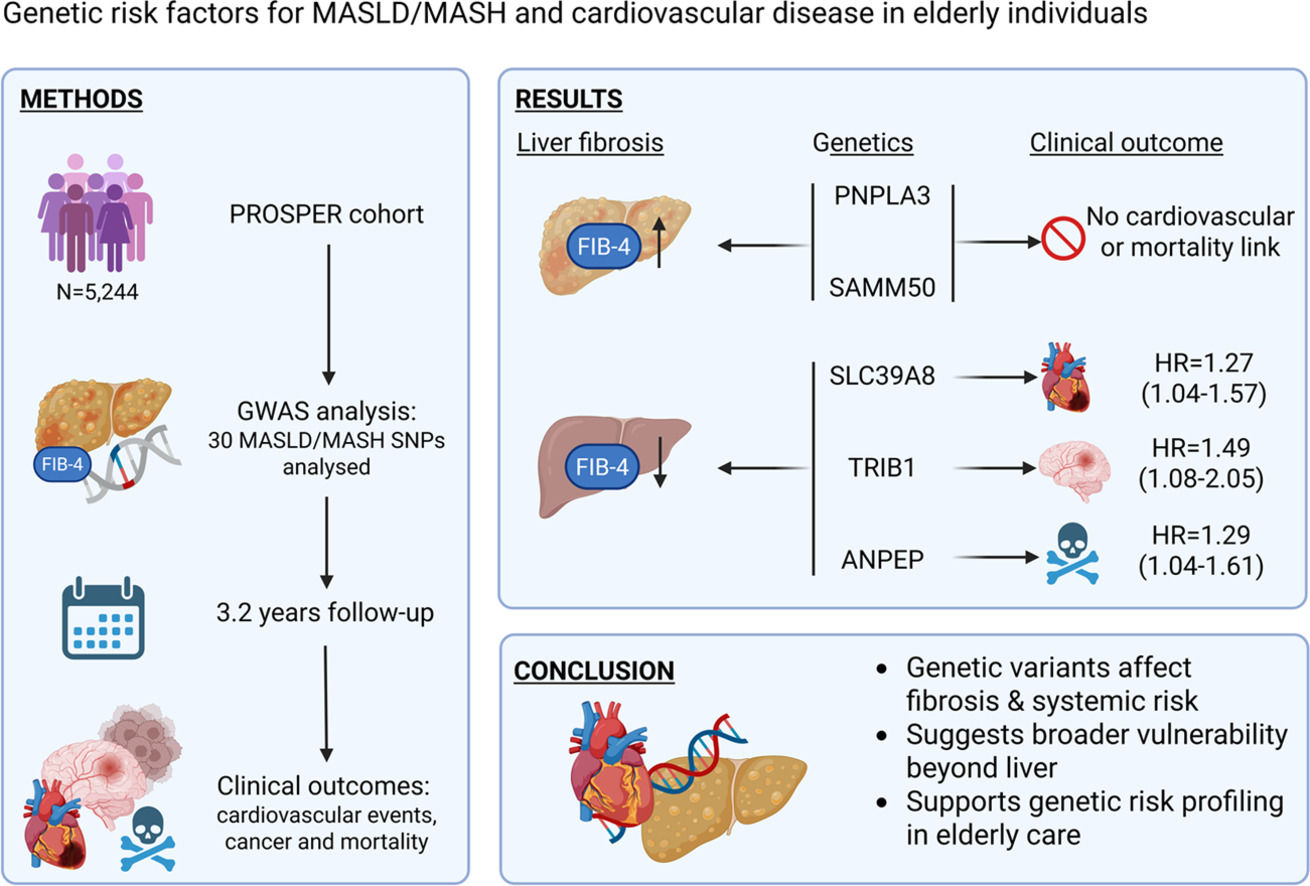

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), previously known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), represents a spectrum of liver conditions characterized by hepatic steatosis in combination with at least one cardiometabolic risk factor such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, or dyslipidemia [1]. MASLD may progress to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), with or without liver fibrosis, and in advanced stages, can lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [2].

Fibrosis is a key prognostic factor in MASLD, as its severity strongly predicts liver-related and overall mortality [3–5]. Beyond hepatic complications, MASLD is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), which remains the leading cause of death in these patients [6–8]. In clinical practice, non-invasive tools such as the Fibrosis-4 Index (FIB-4) are recommended to assess fibrosis risk, especially in settings where liver biopsy is not feasible [9]. Recent data suggest that a high FIB-4 score (≥2.67) is not only linked to liver-related outcomes, but also to increased all-cause mortality and a higher incidence of stroke in patients with obesity [10,11].

The pathogenesis of MASLD is multifactorial and includes insulin resistance, lipotoxicity, gut dysbiosis, and genetic predisposition. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified several genetic variants that influence susceptibility to MASLD and its progression to fibrosis, including polymorphisms in PNPLA3, TM6SF2, HSD17B13, MBOAT7, and GCKR [12–15]. Notably, the rs738409 variant in PNPLA3 and the rs58542926 variant in TM6SF2 are strongly associated with increased liver fat content and fibrosis severity [16].

Recent evidence suggests the existence of two distinct subtypes of MASH: a genetically driven, liver-predominant form with relatively lower cardiovascular risk, and a cardiometabolic form that is closely tied to features like diabetes and cardiovascular complications [17]. However, despite the well-established genetic contributions to MASLD, the link between these polymorphisms and cardiovascular disease remains insufficiently understood. Some studies have even reported that certain MASLD-related single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) may not increase cardiovascular mortality and may potentially offer a protective effect [18–20].

Our group previously demonstrated that a high FIB-4 score predicts all-cause mortality in an elderly cohort and that treatment with pravastatin mitigates this risk [11]. In the present study, we aim to investigate whether well-known MASLD-associated genetic variants contribute to cardiovascular complications in this elderly population.

2Patients and Methods2.1Study population and genotypingThe PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) provided all the data. The PROSPER study was a clinical trial investigating the effect of the cholesterol-lowering drug pravastatin in an elderly population with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (i.e., due to smoking, hypertension, or diabetes). The detailed study set-up has been published in great detail elsewhere [21,22]. Between 1997 and 1999, 5,804 individuals aged 70-82 years from Scotland, Ireland and the Netherlands were included and randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either 40 mg pravastatin or placebo. The study was completed in 2002. The primary composite endpoint was the combined outcome of definite or suspected death from coronary heart disease, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), and fatal or non-fatal stroke, assessed across the entire cohort.

Secondary endpoints included the separate evaluation of coronary and cerebrovascular events. Additionally, subgroup analyses were planned to assess the primary endpoint by sex and by presence or absence of pre-existing cardiovascular disease.

Tertiary endpoints comprised the incidence of transient ischemic attack (TIA), heart failure, cancer, and all-cause mortality. Furthermore, exploratory analyses were intended to examine the potential magnitude of benefit in relation to baseline risk factors such as smoking status, hypertension history, diabetes, and LDL/HDL cholesterol levels.

2.2Genotyping and SNP selectionA genome-wide association screening (GWAS) was performed in the PROSPER/PHASE study using Illumina 660-Quad beadchips, as described previously [23]. The current study focused on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with MASLD [13–15,24] which have been extracted from this PROSPER/PHASE GWAS analysis with PLINK software.

Four recent GWAS studies in the field of MASLD and MASH identified SNPs with robust associations to MASLD and its progressive form, MASH [13–15,24]. These studies yielded 13 SNPs associated with MASH and 44 SNPs linked exclusively to MASLD. Cross-referencing this list of SNPs available in PROSPER, we identified 30 SNPs of interest: 7 associated with MASH and 23 with MASLD. We evaluated them by comparing FIB-4 scores across genotype categories. For SNPs showing significant differences in FIB-4 across genotypes, associations with cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality were assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression models, adjusted for relevant clinical covariates.

2.3FIB-4 indexWe calculated the FIB-4 index as described in recent guidelines to evaluate liver fibrosis [9]. The index was calculated using the patient's age, aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), and blood platelet count [25]. The FIB-4 index was defined as follows:

Since age is a factor in the algorithm used to calculate FIB-4, fibrosis may be overestimated in elderly individuals, resulting in lower sensitivity of FIB-4 in this population. To assess this, we applied age-specific cut-offs as described by McPherson et al [26]: low risk of liver fibrosis (<2.0), intermediate risk (≥2.0 and ≤2.66), and high risk (≥2.67).

2.4Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables are presented as counts and proportions. Descriptive characteristics of the population were provided for each FIB-4 subgroup. Comparisons between subgroups were conducted using a one-way ANOVA. The time-to-event data were analyzed with Cox proportional hazards models for identified SNPs. For each endpoint, either time to first occurrence of the event or study closure (censored observation) was taken, depending on which came first. The models were adjusted for gender, alcohol use, LDL cholesterol levels, and the use of antihypertensives, lipid lowering medication (including pravastatin), and diabetic medications. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each endpoint. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05 assessed with SPSS software version 27.

2.5Ethical ConsiderationsThe medical ethics committees of each participating institution gave their approval to the study protocol. Every study participant provided written, informed consent. The study was compliant with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki's ethical principles.

3Results3.1Population demographicsA total of 5,244 subjects of Caucasian descent with available DNA samples were included in this analysis, of which 51.9% were female, with a mean age of 75.3 years and a mean BMI of 26.8 kg/m². These subjects were followed for a mean of 3.2 years.

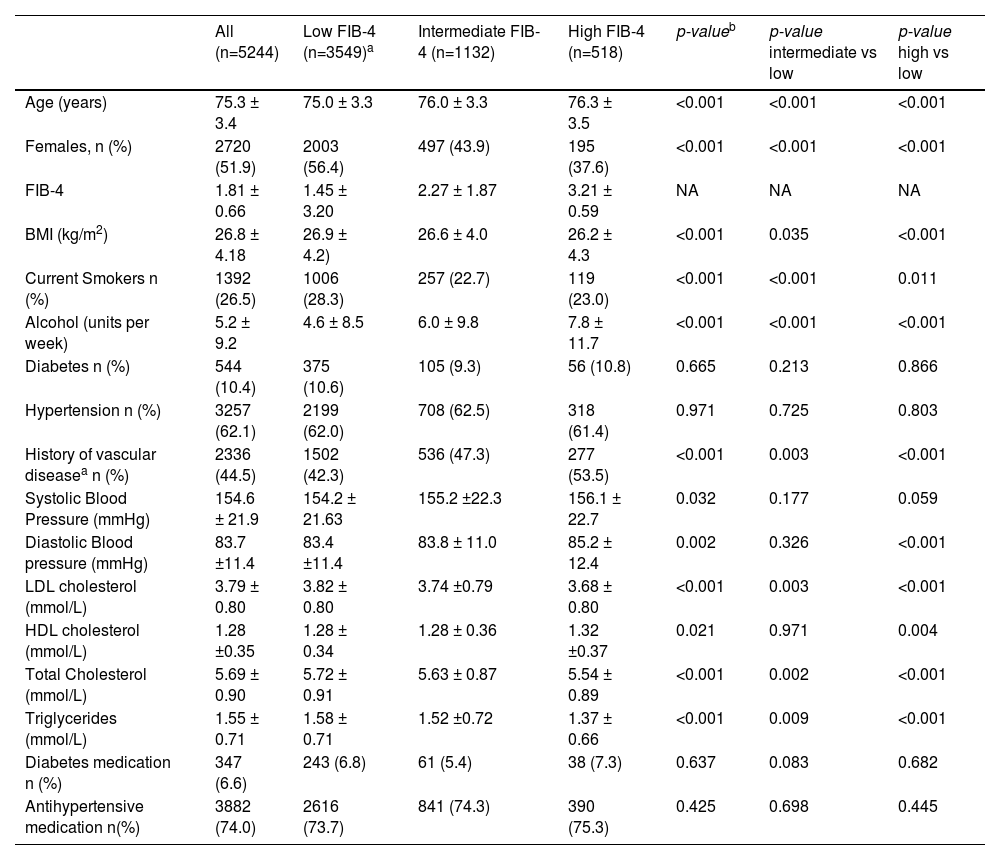

Higher FIB-4 scores were associated with older age, male sex, a history of vascular disease, lower BMI, and a more favorable lipid profile (Table 1). LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides were lower in individuals with high FIB-4, while HDL cholesterol was slightly higher.

Baseline general characteristics of the subjects of the PROSPER study in relation to FIB-4.

| All (n=5244) | Low FIB-4 (n=3549)a | Intermediate FIB-4 (n=1132) | High FIB-4 (n=518) | p-valueb | p-value intermediate vs low | p-value high vs low | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 75.3 ± 3.4 | 75.0 ± 3.3 | 76.0 ± 3.3 | 76.3 ± 3.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Females, n (%) | 2720 (51.9) | 2003 (56.4) | 497 (43.9) | 195 (37.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| FIB-4 | 1.81 ± 0.66 | 1.45 ± 3.20 | 2.27 ± 1.87 | 3.21 ± 0.59 | NA | NA | NA |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.8 ± 4.18 | 26.9 ± 4.2) | 26.6 ± 4.0 | 26.2 ± 4.3 | <0.001 | 0.035 | <0.001 |

| Current Smokers n (%) | 1392 (26.5) | 1006 (28.3) | 257 (22.7) | 119 (23.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.011 |

| Alcohol (units per week) | 5.2 ± 9.2 | 4.6 ± 8.5 | 6.0 ± 9.8 | 7.8 ± 11.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes n (%) | 544 (10.4) | 375 (10.6) | 105 (9.3) | 56 (10.8) | 0.665 | 0.213 | 0.866 |

| Hypertension n (%) | 3257 (62.1) | 2199 (62.0) | 708 (62.5) | 318 (61.4) | 0.971 | 0.725 | 0.803 |

| History of vascular diseasea n (%) | 2336 (44.5) | 1502 (42.3) | 536 (47.3) | 277 (53.5) | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 154.6 ± 21.9 | 154.2 ± 21.63 | 155.2 ±22.3 | 156.1 ± 22.7 | 0.032 | 0.177 | 0.059 |

| Diastolic Blood pressure (mmHg) | 83.7 ±11.4 | 83.4 ±11.4 | 83.8 ± 11.0 | 85.2 ± 12.4 | 0.002 | 0.326 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.79 ± 0.80 | 3.82 ± 0.80 | 3.74 ±0.79 | 3.68 ± 0.80 | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.28 ±0.35 | 1.28 ± 0.34 | 1.28 ± 0.36 | 1.32 ±0.37 | 0.021 | 0.971 | 0.004 |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.69 ± 0.90 | 5.72 ± 0.91 | 5.63 ± 0.87 | 5.54 ± 0.89 | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.55 ± 0.71 | 1.58 ± 0.71 | 1.52 ±0.72 | 1.37 ± 0.66 | <0.001 | 0.009 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes medication n (%) | 347 (6.6) | 243 (6.8) | 61 (5.4) | 38 (7.3) | 0.637 | 0.083 | 0.682 |

| Antihypertensive medication n(%) | 3882 (74.0) | 2616 (73.7) | 841 (74.3) | 390 (75.3) | 0.425 | 0.698 | 0.445 |

Data are presented as number (percentage), mean ±SD, or median ±IQR.

Although no significant differences were observed in the prevalence of hypertension or diabetes, current smoking and alcohol consumption were more frequent in the high FIB-4 group.

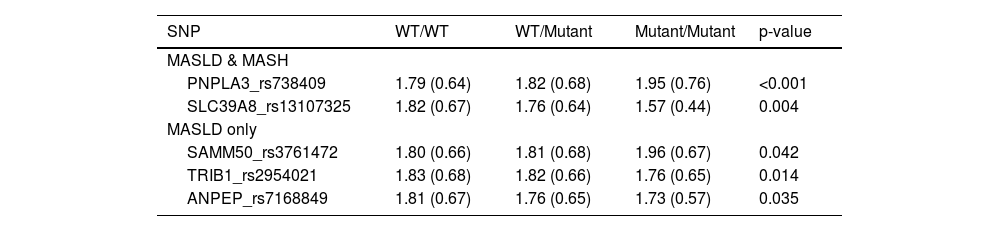

3.2FIB-4 and MASLD/MASH associated SNPsTable 2 presents the association between MASLD/MASH-associated SNPs and FIB-4 classification across genotypes. Only the five SNPs that showed a statistically significant relationship with FIB-4 scores are highlighted in the main text and Table 2 for clarity. The associations for the remaining 25 SNPs, which did not demonstrate significant differences, are included in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table 1) to provide a comprehensive overview.

Association between the MASLD/MASH-associated SNPs and FIB-4 index across genotypic categories.

All data is presented as Mean (SD) FIB-4 risk. WT: wild type

Individuals with the homozygous mutant (M/M) genotype of PNPLA3_rs738409 had significantly higher FIB-4 scores compared to those with the wild-type (WT/WT) genotype. SAMM50_rs3761472 followed the same trend, with the highest FIB-4 score observed in the M/M genotype and the lowest score in the WT/WT genotype.

In contrast, SLC39A8_rs13107325, TRIB1_rs2954021, and ANPEP_rs7168849 exhibited the opposite pattern, where the WT/WT genotype had the highest FIB-4 score, followed by WT/Mutant, and the lowest score was seen in Mutant/Mutant.

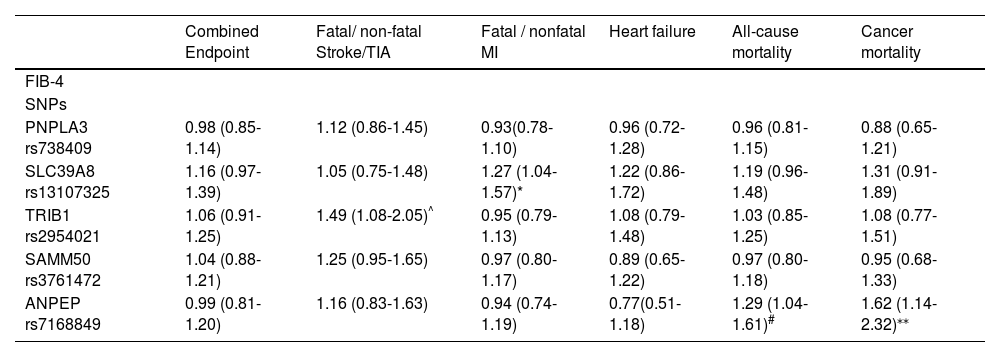

3.3Clinical endpointsThe SNPs that exhibited a significant difference in FIB-4 among the different genotypes were further tested for their associations with cardiovascular and mortality outcomes (Table 3). To improve transparency and interpretability, we also added Supplementary Table 2, which summarizes the number of participants and outcome events per SNP genotype (WT/WT, WT/M, M/M), as well as genotype frequencies.

Association between FIB-4 and related liver fibrosis SNPs with cardiovascular outcomes and cancer. Analysis was conducted using Cox regression and adjusted for statin treatment, gender, alcohol use, LDL cholesterol, and the use of antihypertensive medication and diabetic medication. Data are presented as hazard ratio (95% confidence interval).

| Combined Endpoint | Fatal/ non-fatal Stroke/TIA | Fatal / nonfatal MI | Heart failure | All-cause mortality | Cancer mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIB-4 | ||||||

| SNPs | ||||||

| PNPLA3 rs738409 | 0.98 (0.85-1.14) | 1.12 (0.86-1.45) | 0.93(0.78-1.10) | 0.96 (0.72-1.28) | 0.96 (0.81-1.15) | 0.88 (0.65-1.21) |

| SLC39A8 rs13107325 | 1.16 (0.97-1.39) | 1.05 (0.75-1.48) | 1.27 (1.04-1.57)* | 1.22 (0.86-1.72) | 1.19 (0.96-1.48) | 1.31 (0.91-1.89) |

| TRIB1 rs2954021 | 1.06 (0.91-1.25) | 1.49 (1.08-2.05)^ | 0.95 (0.79-1.13) | 1.08 (0.79-1.48) | 1.03 (0.85-1.25) | 1.08 (0.77-1.51) |

| SAMM50 rs3761472 | 1.04 (0.88-1.21) | 1.25 (0.95-1.65) | 0.97 (0.80-1.17) | 0.89 (0.65-1.22) | 0.97 (0.80-1.18) | 0.95 (0.68-1.33) |

| ANPEP rs7168849 | 0.99 (0.81-1.20) | 1.16 (0.83-1.63) | 0.94 (0.74-1.19) | 0.77(0.51-1.18) | 1.29 (1.04-1.61)# | 1.62 (1.14-2.32)⁎⁎ |

TRIB1_rs2954021 was associated with a higher risk of fatal or nonfatal stroke, while SLC39A8_rs13107325 was linked to an increased risk of fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction. ANPEP_rs7168849 showed significant associations with both all-cause and cancer-specific mortality. PNPLA3_rs738409 showed no significant associations with cardiovascular or cancer-related outcomes, nor did SAMM50_rs3761472.

4DiscussionIn this analysis of 5,244 subjects of the PROSPER study, we identified several key findings regarding the relationship between demographic factors, MASLD/MASH-associated genetic variants, and FIB-4 scores, as well as their potential links to cardiovascular outcomes. First, higher FIB-4 scores were associated with older age, male sex, lower BMI, a history of vascular disease, and a more favorable lipid profile. Second, five genetic variants (PNPLA3_rs738409, SAMM50_rs3761472, SLC39A8_rs13107325, TRIB1_rs2954021, and ANPEP_rs7168849) were significantly associated with FIB-4 classification, with divergent patterns suggesting both risk-enhancing and potentially protective effects. Third, three of these variants (TRIB1, SLC39A8, and ANPEP) were also associated with cardiovascular or mortality endpoints, supporting the notion of shared genetic pathways between liver fibrosis and systemic disease processes.

These findings align well with existing literature and further clarify the interplay between genetic risk and liver fibrosis. The observed association between higher FIB-4 scores and older age, male sex, and vascular disease is consistent with prior studies highlighting fibrosis as a marker of systemic metabolic burden and cumulative organ damage [27,28]. The inverse relationship between FIB-4 and BMI may initially seem paradoxical, but this likely reflects potential confounders like age, metabolic alterations, and muscle catabolism [29–31]. These data support the existence of a "lean fibrosis" phenotype, characterized by metabolic dysfunction despite a lower BMI.

The association of lipid profile changes with FIB-4 scores also mirrors prior findings. Lower LDL, total cholesterol, and triglycerides in individuals with higher FIB-4 scores may reflect impaired hepatic lipid synthesis and transport in advanced liver disease, while slightly elevated HDL cholesterol may indicate compensatory shifts in lipid metabolism [32]. Moreover, the higher prevalence of smoking and alcohol use among those with elevated FIB-4 underscores the contribution of lifestyle factors to fibrotic progression and broader metabolic dysregulation.

Our genetic analysis builds upon established knowledge by reinforcing the role of PNPLA3_rs738409 as a major genetic driver of fibrosis in MASLD and MASH [33,34]. The observed associations with SAMM50_rs3761472 further support its involvement in hepatic mitochondrial function and fibrogenesis. In contrast, SLC39A8_rs13107325, TRIB1_rs2954021, and ANPEP_rs7168849 were associated with lower FIB-4 scores in their mutant homozygous forms, suggesting a potential protective role. This dichotomy in genetic influence reflects variant-specific effects on hepatic inflammation, oxidative stress responses, lipid homeostasis, or immune function [35,36].

Importantly, several of these SNPs also demonstrated associations with cardiovascular outcomes, suggesting that genetic risk for liver fibrosis may also extend to vascular disease. TRIB1_rs2954021 was linked to stroke, consistent with its known effects on lipid metabolism and triglyceride regulation [37]. SLC39A8_rs13107325, associated with myocardial infarction, is known to influence vascular integrity, inflammatory signaling, and oxidative stress response pathways [38,39]. These results support the hypothesis that liver fibrosis and cardiovascular disease share common genetic and pathophysiological mechanisms.

The association between ANPEP_rs7168849 and both all-cause and cancer-specific mortality suggests that this variant may influence processes beyond hepatic fibrosis, potentially via its known roles in immune modulation, extracellular matrix remodeling, and angiogenesis [40–42]. Although previous studies have highlighted altered ANPEP expression in various cancers [43–45], the specific impact of rs7168849 on cancer progression remains underexplored and warrants further investigation.

Interestingly, PNPLA3_rs738409, despite being strongly associated with higher FIB-4 scores, was not linked to cardiovascular or oncological outcomes. This suggests that while PNPLA3 is a potent hepatic risk factor, it may exert limited systemic effects outside the liver, consistent with prior reports [46].

However, recent evidence from Mendelian randomization (MR) studies has challenged this view. In a large two-sample, two-step MR analysis, genetically proxied PNPLA3 inhibition was found to significantly increase the risk of several major cardiovascular diseases, including coronary atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction [47]. The absence of such associations in our study and given the inclusion of older adults (>70 years), may reflect survival bias since individuals with more deleterious genotypes may have developed complications earlier and were therefore not represented in this cohort. MR studies are typically conducted in larger, population-based cohorts, which offer greater statistical power and broader generalizability. In our cohort, individuals carrying the PNPLA3 risk allele who also had high cardiovascular risk may not have survived older age, potentially leading to an attenuation of the observed associations. As Smit and colleagues have elegantly described, genetic variants with strong effects at younger ages may appear to have diminished effects in older cohorts, not because biological pathways have changed, but because of selective survival [48]. In this context, the lack of association between PNPLA3 and cardiovascular endpoints in our study does not necessarily contradict previous findings but rather highlights the importance of age-related bias when interpreting genetic data in elderly populations.

These findings contribute to a growing body of evidence supporting liver fibrosis as a systemic disease marker, with shared genetic determinants that may drive both hepatic and cardiovascular pathology [49,50]. From a clinical perspective, this raises the possibility that genetic profiling could help identify individuals at elevated risk for both advanced fibrosis and cardiovascular disease, enabling targeted prevention strategies.

This study has several strengths. It includes a large, well-characterized study, allowing for robust genetic association analyses. The integration of metabolic, genetic, and cardiovascular outcome data provides a comprehensive view of the interrelated nature of liver and vascular health. We acknowledge that a proportion of participants exceeded the recommended limits for alcohol consumption, raising the possibility of mixed metabolic–alcoholic liver disease (MetALD). While this overlap cannot be fully excluded, alcohol intake was included as a covariate in all adjusted analyses. The observed associations remained robust after adjustment, suggesting that moderate alcohol consumption did not substantially influence the reported genetic associations with liver fibrosis or cardiovascular outcomes.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the cohort may not be fully representative of more diverse populations, which may limit generalizability. Second, we relied on FIB-4 as a non-invasive fibrosis marker rather than histological confirmation. While FIB-4 is widely validated, it has not been specifically validated in elderly populations. Its use in this study was based on its broad applicability and availability within the PROSPER dataset. Biopsy data would have provided more definitive staging. Third, liver-related outcomes were not systematically recorded in the PROSPER trial and were therefore beyond the scope of the present study; cases of liver cancer, when present, were included in the cause-specific mortality analyses. Fourth, mechanistic insights into how specific SNPs influence fibrosis or cardiovascular risk remain speculative and require functional validation. Fifth, although we observed statistically significant differences in FIB-4 scores across several genotypic categories, the absolute FIB-4 values remained within a range typically associated with low risk of advanced liver fibrosis. Therefore, while the findings are relevant for understanding genetic influences on liver fibrosis risk, their immediate clinical implications may be limited.

Finally, it is important to note that our study focused on an elderly population, which may have influenced both the phenotypic expression of genetic variants and the prevalence of comorbid conditions. Age-related changes in liver function, body composition, and vascular health may interact with genetic risk in different ways. Future research should explore these associations in younger cohorts, where genetic predispositions may be more strongly linked to early metabolic changes or subclinical liver fibrosis. Studying younger individuals could help identify at-risk populations earlier in the disease course, potentially enabling more effective prevention strategies and timely interventions.

5ConclusionsIn this analysis, we identified key demographic and genetic determinants of liver fibrosis, as reflected by FIB-4 scores, and demonstrated that several MASLD/MASH-associated genetic variants also influence cardiovascular and mortality outcomes. Our findings underscore the complex interplay between liver fibrosis, systemic metabolic health, and genetic predisposition. While variants such as PNPLA3_rs738409 and SAMM50_rs3761472 were associated with increased fibrosis risk, other SNPs (TRIB1_rs2954021, SLC39A8_rs13107325, and ANPEP_rs7168849) exhibited potential protective or pleiotropic effects that extended beyond the liver to influence cardiovascular and oncological outcomes.

These results highlight the value of incorporating genetic information into the risk stratification of patients with liver fibrosis and support the hypothesis that fibrosis is not only a hepatic condition but also a marker of broader systemic vulnerability. Future research should aim to validate these associations in diverse cohorts, explore underlying mechanisms through functional studies, and assess the utility of genetic screening in guiding personalized management strategies for both liver and cardiovascular disease.

Authors contributionsWilly B. Theel: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft, visualization, Vivian D. de Jong: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft, Diederick E. Grobbee: writing-review & editing, supervision, J. Wouter Jukema: resources, writing-review & editing, supervision, Stella Trompet: methodology, resources, writing-review & editing, visualization, supervision, Manuel Castro Cabezas: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-review & editing, supervision.

None.

The PROSPER study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant obtained from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Prof. Dr. J. W. Jukema is an Established Clinical Investigator of the Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant 2001 D 032). Support for genotyping was provided by the seventh framework program of the European commission (grant 223004) and by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Aging grant 050-060-810).

We thank the PROSPER participants and research staff for their invaluable contributions.