Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a frequent and severe complication of cirrhosis, leading to rapid deterioration and increased mortality. Management varies across Latin America due to differences in disease awareness, diagnostic and therapeutic resources, and healthcare system structures. Standardized guidelines are crucial to improve outcomes.

Materials and MethodsTo evaluate therapeutic strategies and develop region-specific recommendations, the Latin American Association for the Study of the Liver (ALEH) convened 15 experts from 9 countries. The consensus process, conducted in 9 phases using the Nominal Group Technique, included virtual meetings, platform-based collaboration, virtual voting, and two in-person sessions to finalize recommendations and the publication draft.

ResultsThe panel issued 23 recommendations covering the treatment of minimal and overt HE, as well as the prophylaxis and management of recurrent HE in cirrhotic patients.

ConclusionsThis consensus provides updated, evidence-based guidelines emphasizing early diagnosis and effective management. It aims to optimize clinical outcomes, standardize treatment approaches, and enhance patient quality of life. Additionally, these recommendations seek to reduce morbidity, mortality, and hospital readmissions, addressing key challenges in the Latin American healthcare landscape.

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is defined as brain dysfunction due to acute or chronic liver failure and/or portosystemic shunts. The cumulative incidence of HE over 1, 5 and 10 years ranges from 0 % to 21 %, 5 % to 25 %, and 7 % to 42 %, respectively. HE manifests as a syndrome ranging from subclinical neurologic abnormalities to coma, with a wide range of manifestations, including altered sleep patterns, sudden behavioral and personality changes, and cognitive and behavioral abnormalities [1,2]. In patients with cirrhosis and chronic liver failure, multiple factors can trigger the development of HE, including infections, gastrointestinal bleeding, hyponatremia, alcohol, lactic acidosis, and use of certain medications such as sedatives, or diuretic overuse [1–4]. In its overt (clinical) form, HE is a life-threatening decompensation in patients with cirrhosis. However, timely recognition of minimal HE (MHE) is often missed [5]. MHE development is associated with a worsening quality of life for patients and caregivers, higher mortality risk [1,6,7]. and multiple hospital readmissions, and can result in substantial financial costs and a significant burden for patients, caregivers, families and the healthcare system [8–12]. Definitions and general terms related to HE can be found in Appendix A. The use of psychometric or neurophysiological tests is recommended for the diagnosis of MHE. The most widely accepted practice is to perform two different tests, depending on availability and experience, and the diagnosis of MHE is made if both tests are abnormal [8,9]. The diagnosis of overt HE is still a clinical diagnosis. The West Haven scale is the most widely validated tool and can also be used to grade disease severity [8,9,13]. See Appendix B (West Haven criteria for HE severity classification.)

Health systems in Latin America vary significantly. In some countries like Brazil and Costa Rica, tax-funded universal coverage systems have been created to offer health services to the entire population. Other countries such as Argentina, Chile, Mexico and Peru have expanded health coverage by subsidizing medical insurance for low-income and uninsured citizens, pooling funds derived from worker contributions and general taxation. Although this has resulted in improved access to better quality medical services, significant barriers still prevail, as is the case with the level of adherence to healthcare standards and care coordination for patients with chronic diseases. Moreover, there is potentially great local variation in access to quality medical care in different regions [14].

In view of the above, the aim of this consensus was to conduct a review and gain knowledge regarding the standards of HE treatment and prophylaxis; consider a global perspective derived from different representative countries of the Latin American region; and offer updated recommendations for the treatment and prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy.

2Materials and MethodsThe decision to carry out the first Latin American Consensus on Treatment and Prophylaxis of HE emerged as an initiative of the Latin American Association for the Study of the Liver (ALEH). A group of 15 experts from 9 countries in the region (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico and Peru) was selected based on their knowledge of the topic, participation in clinical studies and experience managing patients with HE. The consensus was developed in nine phases, using the Nominal Group Technique (NGT).

Ethical declaration. This consensus was developed with integrity, transparency, and scientific rigor, adhering to ethical principles to ensure unbiased, evidence-based recommendations. Experts provided independent input, considering diverse perspectives and patient-centered care while minimizing conflicts of interest. All decisions were documented for transparency and accountability, ensuring compliance with national and international ethical standards.

Phase 1 – Question standardization. Questions were standardized using the PICO framework. The questions that were answered during the process are found in the results of the consensus (Recommendations).

Phase 2 – Literature search. This phase was split into two stages: defining the search strategy and selecting the papers.

Search strategy: The questions structured by the consensus group were analyzed and used as a basis to develop PICO-based systematic search strategies. These are not described in the article but are available to the reviewers as needed. The comparator was omitted for the sake of sensitivity. Queries were conducted on PubMed, Embase and BVS for all questions. Manual searches were conducted of the reference lists of all the included studies, and relevant articles were added to the study selection. All searches were done in pairs by two independent reviewers and later integrated into a single strategy for each search.

Article selection. A paired selection of articles was done by title and abstract, considering the stated questions. Articles available in full text in English or Spanish were included. In accordance with the methodology, only studies published in the past ten years were included, and clinical trials and systematic reviews were also selected. Selection differences between reviewers were resolved by consensus, in the presence of a third reviewer. The information about the number of selected articles for each question is not described in the article but is available to the reviewers as needed.

Phase 3 – Evidence assessment. Specific tools were used to assess risk of bias in accordance with the design of the primary studies included in the body of evidence for each of the questions. Randomized clinical trials were assessed for the risk of bias using the RoBis tool. For systematic reviews of clinical trials, the RoBis tool was used to assess the quality of the evidence. The references constituting the body of evidence for each of the questions are presented in Appendix C.

Phase 4 – Individual solution or response production. During this phase, each of the experts received the questions, instructions to enter their responses or solutions in a web application, as well as the full text of the articles selected during Phase 2. The experts were asked to attach any references they considered relevant, and which were not found in the application. Individual responses for each of the questions generated during this phase and the final number of articles (including articles selected as part of the search as well as those submitted by the experts) which formed the body of evidence for each of the questions are not included in the article but are available to reviewers as needed.

Phase 5 Additional information verification and processing. Individual responses and submitted supporting evidence were verified and processed to set up the application for the next phase.

Phase 6 – Individual response reviews. In the application, each of the experts reviewed individual responses to the questions of the other experts and was able to revise their own previous responses based on this review. Final individual expert responses are not described in the article but are available to the reviewers as needed.

Phase 7 – Information analysis and synthesis. The final responses from the experts were verified and synthesized by means of affinity matrices, and those which did not meet the recommendation structure were removed. Similar thematic and organization level responses were synthesized into individual recommendations. The results of this process were submitted to the experts during phase 8. The options provided to the expert group during the voting and clarification meetings are not included in the article but are available to the reviewers as needed.

Phase 8 – Asynchronous voting. The experts participated in an asynchronous voting process conducted through the web application for the synthesized options covering all the questions. During this phase, carried out before the synchronous meetings, options for each of the questions were filtered out (responses/recommendations). The options which did not surpass the voting threshold were removed (see threshold description in the next phase).

Phase 9 – In-person clarification and voting meetings. The experts were called to a meeting to carry out repeated sequential processes for each of the consensus questions: 1) text clarification for each response/recommendation; 2) voting on responses/recommendations for each of the questions (only the responses/recommendations surpassing the 30 % threshold in the asynchronous voting of the previous phase were shown and voted); responses/recommendations surpassing the 80 % threshold were considered chosen and the process continued to the next item; 3) voting of individual recommendation level and classsuperscripts [15].

An argument clarification process was opened in those cases in which no agreement was reached in the first voting round, or when two or more options were very close. The experts were given the opportunity to argue for or against each option, and the next voting cycle was initiated once the clarification process was completed. The voting iterations and the recommended versions discussed during the meetings are not included in the article but are available for review as needed.

One question was added at the request of the panel during an in-person meeting, with the participation of all the experts. The question was jointly drafted and favorably voted by 100 % of the experts who also voted to define its evidence level and recommendation class.

3Recomendations3.1Minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE)Question 1: In patients with MHE, is lactulose better than placebo in supporting improvement in these patients?

Recommendation 1: In patients with MHE, the use of lactulose over placebo is suggested, considering that it has been shown to be better at improving cognitive performance and patient quality of life, reverting MHE, and avoiding progression to overt HE, with tolerable side effects.

Class: 1a (100%); Level B-R (93%)

Complementary information

In MHE, the oral administration of 66 % lactulose at a dose of 30–60 ml/day taken 2 to 3 times in a day promotes 2 to 3 daily bowel movements. It appears to be an effective strategy assessed in several studies. One study which compared lactulose effectiveness versus no treatment found that the intervention was significantly better (64.2 % vs. 22.6 %, p = 0.0002) in reverting cognitive decline and improving quality of life. Favorable results were also reported after 90 days of treatment. Published meta-analyses have consistently shown that lactulose is better than placebo or not receiving treatment. The benefits of lactulose remain after 12 months of treatment, showing its short and long-term usefulness [9,16–20].

Question 2: In patients with MHE, is rifaximin better than placebo in achieving improvement in these patients?

Recommendation 2: In patients with MHE, rifaximin administration versus placebo could be a reasonable option, considering that it has shown to be better at improving cognitive performance and patient quality of life, reverting MHE, and avoiding progression to overt HE.

Class: 2a (100%); Level B-R (100%)

Complementary information

In a network meta-analysis that included 25 trials and 1563 participants in total, rifaximin was among the agents found to be effective at reverting MHE when compared to placebo or no treatment (odds ratio [OR]: 7.53; 95 % predictive interval [PrI]: 4.45–12.73; surface under the cumulative ranking curve [SUCRA]: 89.2 %; moderate quality) [17].

The neurofilament-light chain protein reflects neural damage in several neurological diseases and has been proposed as a potential biomarker. A total of 31 patients with MHE received rifaximin treatment. Patients with MHE showed high plasma levels of neurofilament-light chain, which reverted after treatment with rifaximin in those who were responsive. Rifaximin treatment in patients with MHE showed promising results in terms of axonal damage improvement, suggesting that rifaximin can offer therapeutic benefits against disease progression in MHE [21].

In a randomized, double-blind pilot study which included 94 patients with cirrhosis, either placebo (n = 45) or rifaximin (n = 49; 1200 mg/day) were used during an 8-week period. At the end of treatment, MHE had reverted in a significantly higher number of patients in the rifaximin group (75.5 % vs. 20 %; p < 0.0001). Rifaximin was well tolerated [22].

A randomized, open-label, non-inferiority prospective trial included 112 patients with MHE, randomly assigned to group A (lactulose; 30–120 ml/day) or group B (rifaximin tablets; 400 mg three times a day). In the intention to treat analysis (ITT), the proportion of patients in whom MHE had reverted at the three-month point was 73.7 % in the rifaximin group and 69.1 % in the lactulose group (4.6 % difference; 95 % confidence interval [IC]: −9.3 % to 18.4 %). However, non-inferiority of rifaximin versus lactulose could not be demonstrated because the predetermined non-inferiority margin (−5 %) was found within the bilateral 90 % CI of the difference. Significant improvements in quality of life were found in both groups. The proportion of patients with flatulence and diarrhea was significantly higher in the lactulose group [23]. In another study, MHE reversal was observed in 71.42 %, 70.27 % and 11.11 % of patients in the rifaximin, lactulose and placebo groups, respectively (p < 0.001). Rifaximin showed better tolerability when compared to lactulos e [24].

Zacharias et al. found that, compared to placebo or no intervention, rifaximin can improve MHE and health-related quality of life in people with MHE [25]. A more recent study showed that rifaximin achieved significant reduction in progression from MHE to overt HE (OR: 0.17; 95 % CI: 0.04–0.63; p = 0.008) [26].

Question 3: In patients with MHE, is the lactulose/rifaximin combination compared to lactulose or rifaximin alone more effective at supporting improvement in these patients?

Recommendation 3: Data in patients with MHE are limited and there is no well-established evidence suggesting that the lactulose/rifaximin combination is better than monotherapy with either of these drugs.

Class: 2b Weak (100%); Level: C-LD (93%)

Complementary information

Although lactulose or rifaximin alone has been shown to be potentially effective in MHE, no studies supporting their combined use in this condition were found. If combined therapy is considered, treatment should be started with monotherapy as previously stated and, depending on how each individual case evolves, the decision to use combined therapy could be made, extrapolating in this way the conclusions from studies in overt HE which support that the use of this combination could offer additional benefits in terms of higher effectiveness and lower mortality as compared to lactulose alone in patients with overt HE [27].

Question 4: In patients with MHE, is l-ornithine l-aspartate (LOLA) more effective than placebo at improving their condition?

Recommendation 4: In patients with MHE, LOLA would appear to be better than placebo at improving neurocognitive performance and preventing the development of overt HE, although the evidence is inconsistent.

Class: 2a (86%); Level: C-LD (71%). No consensus: the majority vote of the experts was considered.

Complementary information

Although some of the available clinical studies contain biases, according to the available trials, LOLA appears to be an effective alternative in the treatment of MHE [28–32].

The most recently published meta-analysis included six randomized, controlled clinical trials with 292 patients. Compared to placebo or no intervention, LOLA was more effective at reverting MHE (RR = 2.264, 95 % CI = 1.528–3.352, p = 0.000, I² = 0.0 %) and preventing progression to overt HE (RR = 0.220, 95 % CI = 0.076–0.637, p = 0.005, I² = 0.0 %). In this study, LOLA was not found to be better at reducing mortality versus placebo or no intervention [33].

In a study by Alvares-da-Silva et al. [34] although no difference was found between LOLA and placebo in terms of overall MHE improvement, patients who received LOLA had less episodes of overt HE within the following 6 months (5 % vs. 37.9 %, p = 0.016) and showed significant improvement in liver function, as measured with the Child-Pugh and MELD scores (p < 0.001).

According to the view of the experts, LOLA could be considered when lactulose or rifaximin are not available in clinical practice or in case of significant intolerance to those agents.

Question 5: In patients with MHE, are probiotics at least as effective as lactulose or rifaximin in promoting improvement in these patients?

Recommendation 5: Because of the heterogeneity of the studies and the diversity of probiotics used, it is not possible to reach strong conclusions regarding similar effectiveness versus lactulose and rifaximin at improving MHE.

Class 2B (Weak) 86%; Level C-LD: 86%

Complementary information

The disadvantage of most of the studies conducted to assess the use of probiotics in the management of MHE is their low or very low quality and their wide heterogeneity, making it impossible to identify a specific strain strongly associated with MHE improvement. Consequently, high quality clinical trials must be designed to assess the actual efficacy of probiotics in this context. In a study published in 2023, probiotics were more effective at reverting MHE and reducing serum ammonia levels as compared to placebo or no treatment, but not more effective than lactulose or LOLA [29]. A meta-analysis designed to verify the role of probiotics in MHE patients with cirrhosis showed that probiotics can reduce serum ammonia and toxin levels, improve MHE and prevent the development of overt HE [35].

Question 6: In patients with MHE, are branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) at least as effective as lactulose or rifaximin at supporting improvement in these patients?

Recommendation 6: In patients with MHE, BCAA are not as effective as lactulose or rifaximin in contributing to patient improvement.

Class III No benefit: 93%; Level C-LD (100%)

Complementary information

There is no doubt that nutritional support is part of the comprehensive approach to the management of cirrhosis, and supplementation with aromatic branched-chain amino acids to complement daily dietary intake is beneficial [36]. However, specifically in the context of patients with MHE, this strategy is still controversial [37,38]. The same limitations mentioned for probiotic studies are found in the studies that have examined BCAA supplementation for MHE treatment. Consequently, the expert panel was of the view that better quality studies are required before they can be recommended.

Question 7: In patients with MHE, is the use of zinc in monotherapy at least as effective as lactulose or rifaximin in supporting improvement in these patients?

Recommendation 7: In patients with minimal HE, zinc supplementation alone has not shown benefits in terms of clinical improvement when compared to lactulose or rifaximin.

Class III No benefit (Weak): 100%; Level C-LD (100%)

Complementary information

Zinc deficiency is common in patients with cirrhosis and can be a potential trigger of HE. Clinical studies have shown that zinc supplementation could improve psychomotor performance and quality of life in patients with HE, when compared to placebo. It has also been associated with improved cognitive and psychomotor outcomes in these patients, because of blood ammonia level reductions [39–41]. However, zinc supplementation cannot be recommended for the treatment of MHE until better quality studies with a more significant number of patients become available.

3.2Overt hepatic encephalopathy (overt HE)Question 8: In patients with overt HE, is lactulose more effective than placebo in supporting clinical remission?

Recommendation 8: In patients with overt HE, the use of lactulose is recommended over placebo to support clinical remission.

Class: 1 (Strong) 100%; Level: A (100%)

Complementary information

Lactulose, a non-absorbable disaccharide, is the most widely used agent in different Latin American countries, where it is considered first-line treatment for overt HE given its cost-effectiveness. However, other non-absorbable disaccharides such as lactitol, have been shown to be similarly effective. Apart from the association with HE improvement, a random effect meta-analysis showed a beneficial effect of non-absorbable disaccharides on mortality, when compared to placebo or no intervention. Additional analyses showed that non-absorbable disaccharides can help reduce severe adverse events associated with the underlying liver disease, including liver failure, hepatorenal syndrome and variceal bleeding. The secondary outcomes analysis showed a potential beneficial effect of non-absorbable disaccharides on quality of life, although evidence for this item was considered low quality. Non-absorbable disaccharides were associated with non-serious adverse events, mainly gastrointestinal [19,42]. Of the patients with chronic liver disease and overt HE, 78 % usually respond to lactulose. No response ―defined as remaining in HE after 10 days of treatment, or death― has been associated with a high MELD score, high total leukocyte counts, low sodium serum levels, low mean arterial pressure, and the presence of hepatocellular carcinoma [43].

Question 9: In patients with overt HE, is the lactulose/rifaximin combination better than the administration of either lactulose or rifaximin alone to support clinical remission?

Recommendation 9: In patients with overt HE, the lactulose plus rifaximin combination is better that the administration of either lactulose or rifaximin alone in contributing to clinical remission and preventing recurrence, with a potential impact also on improved quality of life, less complications and mortality reduction.

Class 1 (Strong) 100%: Level: A (100%)

Complementary information

The lactulose plus rifaximin combination is more effective than lactulose alone in the treatment of overt HE, and some studies suggest that it could be associated with lower mortality [27,44]. It has also been shown that, compared to lactulose alone, this combination is more effective at reducing the risk of overt HE recurrence and the need for hospital admission [45]. Cost is a concern in relation to this combination; however, a study conducted in the United Kingdom showed that the lower number of admissions as well as shorter lengths of stay associated with rifaximin-α 550 mg twice a day in patients with recurrent episodes of overt HE resulted in cost savings and improved clinical outcomes when compared to standard care over a 5-year period [46].

Additionally, a retrospective study which included patients with HE, showed that rifaximin reduced the risk of HE recurrence and was significantly associated with higher overall survival and a lower risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or variceal bleeding. The same study shows evidence of a of 2.35 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and 1.83 QALYs per subject benefit [47].

Question 10: In patients with severe overt HE, West Haven grades III and IV, is the lactulose/rifaximin/LOLA combination better than the administration of these agents as monotherapy or dual therapy in supporting clinical remission?

Recommendation 10: In patients with over-hepatic encephalopathy (West Haven grades III and IV), the combination of lactulose plus rifaximin plus LOLA is better than the administration of these agents as monotherapy in supporting clinical remission, reducing mortality and improving HE sooner and more effectively.

Class IIa (Moderate): 93%; Level: B-R 93%

Complementary information

Two recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials have examined LOLA administration at a dose of 30 g as intravenous infusion over 24 h for 5 days, showing clinical improvement in severe overt HE (West Haven grades III and IV). In the study by Sidhu SS et al., the standard of care (including lactulose and ceftriaxone) was administered in both groups and, additionally, one group received placebo and the other received LOLA. Mean recovery time was shorter in the LOLA group compared to the placebo group (1.92 ± 0.93 vs. 2.50 ± 1.03 days, p = 0.002; 95 % CI −0852 to −0202). Venous ammonia levels on day 5 and hospital length of stay were significantly lower in the LOLA group. [47] In the study by Jain A et al., one group received a combination of LOLA, lactulose and rifaximin (n = 70), while the other group received placebo, lactulose and rifaximin (n = 70). The comparison between the LOLA and the placebo groups showed higher rates of improvement in HE grades (92.5 % vs. 66 %, p < 0.001), shorter time to recovery (2.70 ± 0.46 vs. 3.00 ± 0.87 days, p = 0.03) and lower 28-day mortality (16.4 % vs. 41.8 %, p = 0.001). Reductions in blood ammonia, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α levels were significantly greater in the LOLA group [48].

Question 11: According to the current evidence on overt HE, can polyethylene glycol (PEG) be considered better than lactulose in supporting clinical remission?

Recommendation 11: Sufficient evidence showing that PEG is better than lactulose in overt HE is not yet available.

Class IIb (Weak): 93%; Level C-LD: 86%

Complementary information

Compared to lactulose, patients treated with PEG showed a significantly lower score in the Hepatic Encephalopathy Score Algorithm (HESA) at 24 h; there was a higher proportion of patients with a lower HESA score grade ≥1 at 24 h, a higher proportion of patients with grade 0 HESA score at 24 h, and shorter resolution time. However, all these studies have a high risk of bias, particularly because they are not blinded [49,50], and because of potential reporting and selection bias [49]. In view of its effectiveness and safety, PEG could be considered in the future as an option for patients without adequate tolerance to lactulose; however, better quality studies to validate its usefulness are required.

Question 12: In patients with severe overt HE, West Haven grades III and IV, can lactose or lactulose enemas be considered an alternative to the administration of oral non-absorbable disaccharides when oral intake is not possible?

Recommendation 12: In patients with severe overt HE (West Haven grades III and IV), the use of lactose or lactulose enemas could be considered as an alternative to the administration of oral non-absorbable disaccharides when oral intake is not possible.

Class IIb (Weak): 86%; Level C-LD: 100%

Complementary information

There are very few significantly heterogenous studies, with insufficient sample sizes and potentially relevant methodological biases that have examined the administration of lactilol or lactulose enemas. These studies suggest that these acidifying agents can be effective for the treatment of severe episodic overt HE [51–54]; consequently, they could be used when other specific therapeutic measures are not available.

3.3Primary prophylaxis in hepatic encephalopathyQuestion 13: Is primary prophylaxis with lactulose more effective than placebo in preventing the development of HE?

Recommendation 13:

- •

Evidence supporting the indication of lactulose as primary prophylaxis in patients with cirrhosis is limited.

Class IIb (Weak): 86%; Level C-LD: 100%

- •

The use of primary prophylaxis with lactulose is recommended in patients with cirrhosis and upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Class I (Strong): 93%; Level B-R: 100%

- •

Evidence to recommend the use of lactulose alone in primary prophylaxis after placement of trans-jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is insufficient.

Class III No benefit (Weak): 93%; Level B-R: 100%

Complementary information

In patients with cirrhosis who had never had an episode of overt HE, Sharma P et al. conducted an open-label clinical trial to compare the group that received lactulose vs. the no intervention group, with monthly follow-up during a 12-month period. The proportion of patients who developed overt HE was smaller in the lactulose group (11 % vs. 28 %, p = 0.02), reflecting that lactulose administration was an effective primary prevention strategy [55]. A meta-analysis also showed that non-absorbable disaccharides prevent HE development (RR = 0.47, 95 % CI 0.33–0.68, number needed to treat [NNT] = 6) and were also found to reduce the risk of developing serious liver-related adverse events (RR = 0.48, 95 % CI 0.33–0.70, NNT = 6), and to reduce mortality (RR = 0.63, 95 % CI 0.40–0.98, NNT = 20).

Adverse effects were gastrointestinal and not serious [43]. Although risk factors usually considered by treating physicians as a reason to initiate prophylaxis in order to prevent the development of overt HE are constipation (56.35 %), followed by infections (25.89 %) and gastrointestinal bleeding (17.77 %) [56], it is well known that up to 40 % of patients with cirrhosis who present with gastrointestinal bleeding also develop overt HE, a condition which is associated with increased mortality. There is strong evidence to support the efficacy of primary prophylaxis in this group of patients [57].

A systematic review of the literature, including randomized controlled clinical trials which assessed the efficacy of lactulose as primary prophylaxis for HE in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, found that the incidence of HE in those who received the intervention was lower than in those who did not (7 % vs. 26 %; p = 0.01) [58]. More recently, a randomized single-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial by Sharma P et al., showed that the incidence of HE was lower in patients with acute variceal hemorrhage (AVH) treated with oral lactulose for five days at a dose of 30–60 mL, split into two or three administrations in order to achieve two or three bowel movements a day (14 % vs. 40 %, p = 0.02) [59]. Wen J et al. confirmed the efficacy of lactulose in this clinical setting [60].

In a systematic review and meta-analysis carried out by Liang A et al., following TIPS placement, lactulose, lactitol, LOLA and albumin-based prophylaxis were not associated with reduced HE occurrence or lower mortality. However, the rifaximin/lactulose combination was associated with reduced HE occurrence [61].

Question 14: Is primary prophylaxis with rifaximin more effective than placebo in preventing the onset of HE?

Recommendation 14: Evidence to recommend rifaximin in primary prophylaxis is insufficient; however, after TIPS placement, it could be reasonable to use primary prophylaxis with rifaximin plus lactulose.

Class IIa (Moderate): 100%; Level: B-R: 100%

Complementary information

In a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, which included 197 patients with cirrhosis caused by high alcohol consumption taken to TIPS due to intractable ascites or to prevent new variceal bleeding, patients were randomized to receive rifaximin (600 mg twice a day) or placebo, starting 14 days before the TIPS procedure and extending for 168 days after. During the follow-up period after the procedure, an episode of overt HE occurred in 34 % of patients in the rifaximin group vs. 53 % of in the placebo group (OR, 0.48; CI, 0.27–0.87). Neither the incidence of adverse events nor transplant-free survival were significantly different between the two groups. The conclusion of the study applies mainly to the study population, i.e., patients with cirrhosis due to alcohol abuse. The potential benefit of rifaximin beyond six months after the TIPS procedure has not been studied so far [62].

In the meta-analysis by Lian A et al., rifaximin alone was not effective at preventing the first episode of overt HE after TIPS placement; in contrast, the rifaximin/lactulose combination was associated with lower HE occurrence [61].

Question 15: Is primary prophylaxis with LOLA more effective or at least as effective as lactulose in preventing the onset of HE?

Recommendation 15:

Evidence to support the efficacy of LOLA in primary prophylaxis is insufficient.

Class IIa (Moderate): 100% – Level B-R: 100%

In patients with cirrhosis and variceal hemorrhage it is reasonable to use l-ornithine l-aspartate (LOLA) for primary prophylaxis.

Class IIa (Moderate): 100% – Level B-R: 100%

Complementary information

Lactulose is the most recommended strategy in the context of patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding, primarily to prevent the occurrence of overt HE. [58–60] However, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial which included patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding without MHE or overt HE at baseline, found that, compared to placebo, the frequency of overt HE development was the next lowest among those who received LOLA (54.5 % vs. 22.7 %; OR = 0.2, 95 % CI 0.06–0.88; p = 0.03), and among those who received rifaximin (54.5 % vs. 23,8 %; OR = 0.3, 95 % CI 0.07–0.9; p = 0.04). Though lactulose did not achieve statistical significance in this study, neither were there significant differences between the three groups that received an anti-ammonia drug (p = 0.94) [63]. Compared to placebo or no intervention, LOLA was effective as primary prophylaxis for overt HE following acute variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis (RR: 0.42; 95 % CI: 0.16–0.98; p < 0.03) [64].

A potential synergistic effect of the various anti-ammonia strategies in this context has not been explored.

Evidence to recommend LOLA administration after TIPS placement in patients with cirrhosis is insufficient [65].

Question 16: Is primary prophylaxis with probiotics more effective or at least as effective as primary prophylaxis with lactulose in avoiding HE onset?

Recommendation 16: The use of probiotics as primary prophylaxis is not recommended given the lack of sufficient evidence that could indicate that they are more effective than lactulose.

Class III No benefit (Weak): 93%; Level C-LD: 93%

Complementary information

While this field is promising, most of the studies that have examined the use of probiotics in the management of HE had a high risk of systematic and random error (bias and random error). Consequently, the evidence is of very low quality. Compared to placebo or no intervention, probiotics could probably improve recovery from HE, prevent progression of MHE to overt HE, and improve quality of life and plasma ammonia concentrations. Because of its very low quality, the evidence currently available does not allow us to determine with any certainty whether probiotics are better than lactulose [66].

Question 17: Is primary prophylaxis with branched-chain amino acids (BCCA) more effective or at least as effective as lactulose prophylaxis to prevent the onset of HE?

Recommendation 17: BCAAs are not recommended as primary prophylaxis in HE because the evidence indicating that they are more effective than non-absorbable disaccharides is insufficient.

Class III No benefit (Weak): 100%; Level C-LD: 100%

Complementary information

Besides showing that BCAA administration improved nutritional status, Du JY et al. found that the complication rate in patients with cirrhosis dropped and that serum albumin levels improved [67]. Additionally, a meta-analysis found that BCAA administration can improve HE (the strongest evidence focuses on overt HE) but that it has no effect on mortality, quality of life or nutritional parameters. The authors of this study concluded that additional trials are needed to evaluate these results. Moreover, additional randomized clinical trials are required in order to determine the effects of BCAAs when compared to interventions such as non-absorbable disaccharides, rifaximin or other antibiotics [68]. As concerns primary prophylaxis, the paucity of evidence is greater still.

Question 18: Is primary prophylaxis with zinc supplements more effective or at least as effective as prophylaxis with oral non-absorbable disaccharides in avoiding HE onset?

Recommendation 18: Zinc supplementation as primary prophylaxis is not recommended because the evidence indicating that it is more effective than non-absorbable disaccharides is insufficient.

Class: III No benefit (Weak): 93%; Level: C-LD: 100%

Complementary information

Low serum zinc levels are associated with HE, but the efficacy of zinc supplementation is still uncertain. A meta-analysis examined zinc supplementation, specifically as adjunct therapy, and found that in patients with cirrhosis and mild HE (≤ grade II), combined treatment with zinc supplements plus lactulose during 3 to 6 months significantly improved patient performance in the number connection test. However, when compared with lactulose alone, additional zinc supplementation did not result in a significant difference in the symbols and digits test or in serum ammonia levels, and there was no increase in adverse effects either [69]. In the field of prophylaxis, there are no studies that have explored whether zinc supplementation could be effective; consequently, it cannot be recommended at this point because of the lack of studies validating this strategy.

3.4Recurrent hepatic encephalopathyQuestion 19: Is lactulose more effective than placebo in reducing HE recurrence?

Recommendation 19: The use of lactulose to diminish HE recurrence is recommended.

Class I (Strong): 100%; Level A: 100%

Complementary information

Long-term lactulose administration (median of 4 months, range 1–20 months) has been shown to be more effective than placebo or no intervention in averting the recurrence of overt HE (19.6 % vs. 46.8 %; p = 0.001) [70]. Overt HE recurrence was associated with the presence of two or more abnormal psychometric tests and high arterial ammonia levels after recovery from an HE episode 38.

A meta-analysis of 5 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) which compared lactulose vs. placebo showed that, in all the studies, lactulose therapy was associated with a significantly lower risk of overt HE as compared to placebo, with a RR of 0.38. Lactulose has a significant impact on HE prevention.

Question 20: Is rifaximin more effective than placebo in diminishing HE recurrence?

Recommendation 20: Rifaximin has been shown to be more effective than placebo in reducing HE recurrence.

Class I (Strong): 100%; Level A: 100%

Complementary information

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study showed a strong protective effect of rifaximin against HE episodes. Rifaximin also reduced the risk of HE-related hospitalization [71].

Recent evidence also suggests that the use of rifaximin alone can be appropriate for patients in whom lactulose is ineffective or poorly tolerated, or when adherence to lactulose therapy is challenging. However, further research is required to confirm this option 38.

The meta-analysis reported that rifaximin had a beneficial effect in secondary prevention of HE and increased the proportion of patients who recovered from HE. Rifaximin was given at a dose of 1100 to 1200 mg/day, and treatment duration ranged between 5 and 180 days [72].

A dose of 400 mg three times a day or 600 mg twice a day of rifaximin could be considered for secondary prevention in patients with minimal HE [73].

According to the results of a Cochrane analysis, long-term rifaximin use to prevent HE can be effective in reducing the risk of recurrence when compared with lactulose alone.

Question 21: Is the lactulose/rifaximin combination more effective in reducing HE recurrence than lactulose or rifaximin alone?

Recommendation 21: The use of rifaximin and lactulose as combined therapy is recommended over the use of either drug alone to reduce HE recurrence.

Class I (Strong): 100%; Level A: 100%

Complementary information

Adding rifaximin to lactulose significantly reduces the risk of overt HE recurrence and HE-related hospitalization, as compared to lactulose alone.

Studies have shown that lactulose is effective in preventing overt HE recurrence long-term and that adding rifaximin to lactulose significantly reduces the risk of MHE recurrence and HE-related hospitalization as compared to lactulose alone, without compromising tolerability. Adding rifaximin to standard lactulose-based therapy can result in substantial long-term reduction in the use of medical resources, as it reduces MHE recurrence and associated re-admissions. The rifaximin/lactulose combination significantly reduces the risk of MHE and HE-related hospitalization compared to the use of lactulose alone [74].

Question 22: Is there any evidence showing that LOLA is a more effective therapy than placebo in reducing HE recurrence?

Recommendation 22: Prescribing oral LOLA can be useful to diminish HE recurrence.

Class IIa (Moderate): 86%; Level B-R: 93%

Complementary information

Reports on primary or secondary prophylaxis of HE using LOLA in patients with cirrhosis are limited. A randomized, double-blind clinical trial with LOLA in secondary prophylaxis of HE in 150 patients with cirrhosis has been published. The odds of developing HE dropped significantly in the group treated with LOLA and the time to the first episode of overt HE was significantly longer when compared to placebo. These benefits occurred together with improvement in psychomotor test scores and critical blinking frequency parameters, with significant reductions in arterial ammonia levels. Emerging evidence derived from individual randomized controlled trials shows the efficacy of LOLA in the treatment of HE after TIPS, as well as in secondary HE prophylaxis. These findings support the use of LOLA in the treatment of HE, and future trials should focus on its use as prophylaxis [75,76].

In a secondary prophylaxis study, oral LOLA was administered at a dose of 6 g three times a day for 6 months to patients with a recent episode of overt HE. A significantly lower recurrence was found in the group receiving LOLA vs. placebo (12.3 vs. 27.7 %). LOLA was also found to be associated with improved psychometric scores, ammonia levels and quality of life in HE [76,77].

Further studies in more homogeneous populations are needed in order to establish the route of administration, the dose and the optimal settings in which the greatest benefits for the patients can be obtained, thus strengthening the evidence level of the recommendation.

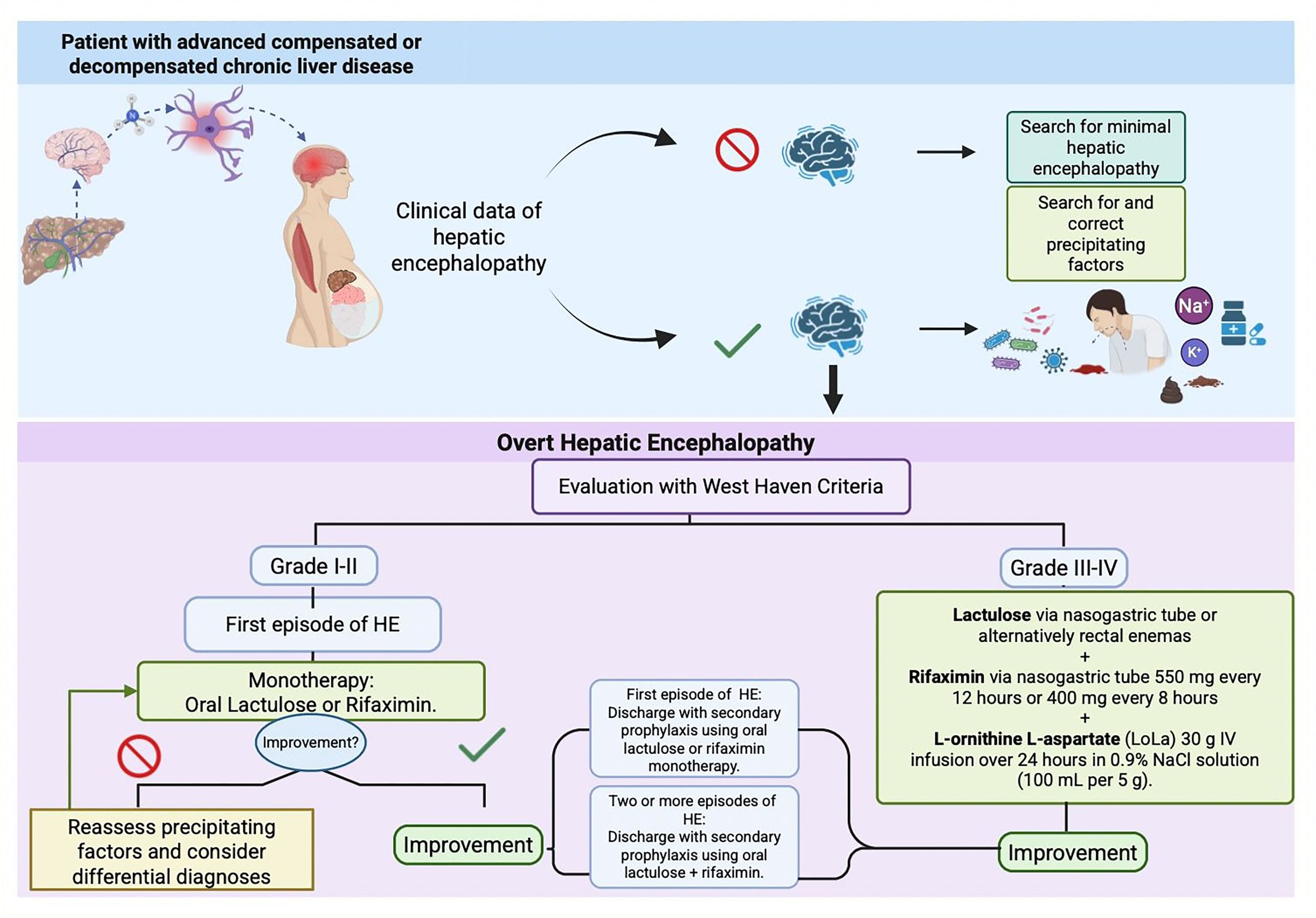

3.5Decision-making algorithm in minimal and overt hepatic encephalopathyThe algorithm shown below (Fig. 1), which summarizes decision-making in minimal and overt hepatic encephalopathy was developed based on the review of the evidence on this topic, real world experience managing these patients and the recommendations of this consensus.

3.6Precipitating factorsThe main triggers of HE episodes include constipation, infections, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, diuretics, electrolyte or acid-base imbalances, and dehydration. Timely identification and management of these precipitating factors is critical in patients with HE.

Decision-making in minimal and overt hepatic encephalopathy Algorithm (developed based on the review of the evidence on this topic, real world experience managing these patients and the recommendations of this consensus)

(See Appendix D (Therapeutic options for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy), Appendix E (Characteristics of the medications most widely used in the management of hepatic encephalopathy), and Appendix F (Nutritional recommendations in patients with HE).

4ConclusionsThe aim of this consensus was to approach HE from a comprehensive perspective, emphasizing early diagnosis and adequate management.

The recommendations resulting from this consensus are expected to be a valuable tool for healthcare professionals involved in the care of these patients, and to provide clear and updated guidance that can be applied in daily clinical practice to optimize outcomes in this complex group of patients.

Likewise, these recommendations seek to improve patient quality of life and reduce mortality as well as associated hospital readmission rates. Finally, the importance of furthering research for the development of new therapies focused on HE prevention and treatment in Latin America is highlighted.

Authors’ contributionsF.HT, GE.CN, and M.RAS contributed to the conceptualization of the consensus project, the formulation of its objectives, the definition of the methodology, the acquisition of funding, and the drafting of the questions to be addressed in the consensus. They also participated in the validation process, review the evidence, answering of the formulated questions, and attended both in-person and virtual sessions for reviewing recommendations, making adjustments, voting, and classifying the evidence. Additionally, they provided the theoretical section of the article. They have reviewed both the draft and the final version of the manuscript. J.BG., E.C., J.G., HA.HM., G.H., J.ML., M.M., GG.MP., C.PMSO., M.GP., Y.SQ., JA.V-RV., were involved in the validation process, the review of the evidence, and the formulation of responses to the consensus questions. They actively participated in both in-person and virtual sessions to review recommendations, suggest adjustments, vote, and classify the evidence. Additionally, they reviewed the original draft of the article, providing comments and recommendations for improvement, and contributed to the development of the theoretical section. The authors also collaborated on drafting and approving the good practice points, securing funding, and reviewing and approving the final version of the article for submission.

FundingFunded by ALEH’s own resources, with partial financial support from Merz Pharma.

C. PMSO has received consulting fees from Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim; has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, or speaker bureaus from Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Inventiva, and Boehringer Ingelheim; and has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Merz. CY. SQ received support for the present manuscript from Merz. JA. V-RV received support for the present manuscript from Merz in the form of economic support to the Latin American Association for the Study of the Liver to perform this consensus and has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, and speaker bureaus from Megalabs and Alfa Sigma.F. H-T received support for the present manuscript from Merz in the form of economic support to the Latin American Association for the Study of the Liver to perform this consensus. HA. HM received support for the present manuscript from Merz in the form of economic support to the Latin American Association for the Study of the Liver to perform this consensus and has also received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Merz Therapeutics. M-G. P received support for the present manuscript from Merz in the form of funding for the present meeting; has received grants or contracts from GSK and Takroa; has received consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Novo Nordisk; has received payments or honoraria for lectures, presentations, and speaker bureaus from Novo Nordisk; and has participated as Vice President and President of ALEH. G. HC received support for the present manuscript from Merz in the form of economic support to the Latin American Association for the Study of the Liver to perform this consensus. J. ML received support for the present manuscript from Merz and has served as the President of the Ethical Committee at Hospital Luis Vernaza, Guayaquil. M.RAS received support for the present manuscript from Merz in the form of funding for the present meeting in the form of travel expenses; has received grants or contracts from CNPq-National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, Brazil; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biolap, Genfit, Ipsen, Merz, Novo Nordisk, Roche; has received payment honoraria for lectures, presentations and speakers bureaus from AstraZeneca, Biolab, Hypera, Ipsen, Merz and Novo Nordisk; has received support for attending meetings from NovoNordisk, Merz; has been part of data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Astrazeneca, Bayer, Biolab, Genfit, Merz, Novo Nordisk and Roche; and has received equipment materials, drugs or medical writing from Echosens. G. MP, GE. CN, J. G-R, M. M, CY. SQ, and E. CE have nothing to declare.

We thank ALEH for the facilities provided to carry out this consensus and Merz Pharma for their support and sponsorship in making this consensus possible. In addition, Medical writing support was provided by Integralis HGS (Daniel Rodríguez, MD, and María Stella Salazar, MD.), who contributed to the drafting and editing of the manuscript in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines.